Abstract

The control of mosquitoes is threatened by the appearance of insecticide resistance and therefore new control chemicals are urgently required. Here we show that inhibitors of mosquito peptidyl dipeptidase, a peptidase related to mammalian angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), are insecticidal to larvae of the mosquitoes, Aedes aegypti and Anopheles gambiae. ACE inhibitors (captopril, fosinopril and fosinoprilat) and two peptides (trypsin-modulating oostatic factor/TMOF and a bradykinin-potentiating peptide, BPP-12b) were all inhibitors of the larval ACE activity of both mosquitoes. Two inhibitors, captopril and fosinopril (a pro-drug ester of fosinoprilat), were tested for larvicidal activity. Within 24 h captopril had killed >90% of the early instars of both species with 3rd instars showing greater resistance. Mortality was also high within 24 h of exposure of 1st, 2nd and 3rd instars of An. gambiae to fosinopril. Fosinopril was also toxic to Ae. aegypti larvae, although the 1st instars appeared to be less susceptible to this pro-drug even after 72 h exposure. Homology models of the larval An. gambiae ACE proteins (AnoACE2 and AnoACE3) reveal structural differences compared to human ACE, suggesting that structure-based drug design offers a fruitful approach to the development of selective inhibitors of mosquito ACE enzymes as novel larvicides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The mosquitoes Anopheles gambiae and Aedes aegypti are some of the most deadly insects because of their effectiveness as vectors of malaria and a range of arboviruses, including yellow fever, dengue, chikungunya and zika. The close association of Ae. aegypti with urbanisation in tropical and sub-tropical countries and the ease of trans-global human travel and the mass migrations from war zones presents particular challenges in disrupting the cycle of arbovirus infections transmitted by Ae. aegypti in human populations1,2. The lack of effective vaccines and treatments for dengue, chikungunya and zika has focused attention on integrated vector control management based on environmental/cultural management, chemical and biological control2. The use of insecticides from different chemical classes is a key component of the integrated strategy against both An. gambiae and Ae. aegypti, but the ever increasing problem of insecticide resistance means that new compounds with different modes of action are urgently needed to replace chemicals that fail to control resistant mosquito populations3,4,5,6.

In our search for new insecticide targets that interfere with peptide hormone metabolism, we have previously identified a peptide-degrading zinc-metallopeptidase, known as angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) from the role of the mammalian enzyme in the renin-angiotensin systems7,8,9, as a potential target for the development of inhibitors that disrupt insect reproduction. The dual role of the enzyme in the processing of the mammalian vasoconstrictor angiotensin II and the inactivation of the vasodilatory bradykinin led to the development of inhibitors of human ACE as anti-hypertensive drugs10,11,12. The first inhibitors were in fact natural proline-rich peptides (BPPs) with bradykinin-potentiating activity isolated from the venom of the snake Bothrops jararaca, but these lacked oral activity13,14,15.

Insect ACE, like the mammalian enzyme, is a promiscuous peptidase that cleaves dipeptides from the carboxyl end of oligopeptides and, in some instances, can cleave amidated di- or tri-peptides from substrates with an amidated carboxyl terminus, a common feature of insect neuropeptides16,17,18,19,20,21. Insect ACEs are generally soluble enzymes secreted from cells into the extracellular milieu, where like their mammalian counterparts they degrade peptides by sequential removal of dipeptides16,22,23,24. Much of our knowledge of the biochemistry and structural biology of insect ACE comes from studying the Drosophila melanogaster enzyme known as AnCE21,25. This peptidyl dipeptidase is strongly expressed as a glycosylated protein of 72 kDa in several tissues, including male reproductive tissues, the larval and adult midgut, larval trachea and adult salivary gland26,27. Other insect species also express ACE in reproductive tissues of both sexes, suggesting a broader physiological role for the enzyme in insect reproduction19,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. Insect ACE not only resembles the mammalian enzyme in its substrate specificity, but also in susceptibility to inhibitors such as captopril, lisinopril, fosinoprilat, enalapril and trandolaprilat, but apart from captopril these inhibitors can be far less potent towards insect ACE compared to mammalian ACE22,23. Nevertheless, ACE inhibitors can be acutely toxic to insects, which contrasts with their life-span extending properties in rodents37 and the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans38. They have been useful in confirming important roles for ACE in reproduction, growth and development in several insect species30,34,35,39. In the mosquito Anopheles stephensi, females fed with ACE inhibitors in the blood meal or females mated with males supplied with ACE inhibitors in their sugar diet, lay significantly fewer eggs than normal32,35,40.

ACE inhibitors can also interfere with insect larval development as was shown by the stunting of larval growth of the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta, by injection of captopril, lisinopril and fosinoprilat into 4th instar insects. Injection of the prodrug fosinopril into the same larval stages resulted in no weight gain and death within a few days. The injection of ACE inhibitors (captopril, lisinopril and enalapril) combined with the diuretic peptides (helicokinin I, II and III) into 5th instar larvae of the tobacco budworm (Heliothis virescens) resulted in lethality, however, the inhibitors on their own were not toxic. In the present study we have asked the question whether mosquito larval stages, like the juvenile stages of some other insect species, are susceptible to ACE inhibitors. We now show that several synthetic ACE inhibitors are powerful blockers of the peptidyl dipeptidase activity found in a soluble fraction from both Ae. aegypti and An. gambiae larvae. The snake venom peptide BPP-12b, and the proline-rich trypsin-modulating oostatic factor (TMOF), which is toxic to Ae. aegypti larvae41, also inhibited the larval peptidase activity. When captopril and fosinopril (Fig. 1), two inhibitors with different modes of interaction with the ACE active site, were added to the rearing water high levels of larval mortality of were observed confirming the potential of insect ACE inhibitors as mosquito larvicides.

Results and Discussion

Inhibition of the soluble peptidyl dipeptidase (insect ACE) activity from whole larvae of Ae. aegypti and An. gambiae

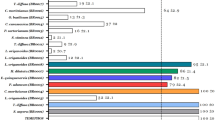

Members of the insect ACE family of peptidyl dipeptidases are generally soluble secreted proteins, whereas mammalian ACEs are mainly membrane tethered. In order to ascertain whether the ACE activity of the mosquito larvae was soluble or membrane-bound, homogenates were prepared from 3rd instar Ae. aegypti and An. gambiae and centrifuged at 55,000 g for 1 h to sediment cellular membranes. By measuring the peptidase activity before and after centrifugation, it was clear that the majority of the insect ACE remained in the high-speed supernatant and that most of the peptidase activity was inhibited by captopril (Fig. 2). The soluble enzyme from both mosquito species was then used to determine the relative potency of synthetic (captopril, fosinopril and fosinoprilat) and natural peptide (BPP-12b and TMOF) ACE inhibitors. Apart from the pro-drug fosinopril, all the inhibitors showed a greater degree of potency towards the Ae. aegypti activity, with captopril being the most potent (Fig. 3). For the enzyme prepared from both species, fosinopril was weaker than the non-esterified fosinoprilat in inhibiting the activity. The snake venom peptide BPP-12b and the mosquito peptide TMOF both inhibited mosquito ACE activity, but were much less potent than the synthetic compounds with BPP-12b having IC50 values two orders of magnitude lower than those of TMOF. Interestingly, both natural peptides were stronger inhibitors of the Ae. aegypti ACE compared to An. gambiae (Table 1).

Inhibition of the peptidyl dipeptidase (ACE) activity of (a) Ae. aegypti and (b) An. gambiae larvae. Inhibition curves for captopril, fosinopril, fosinoprilat, PBB12b and TMOF were generated by assaying peptidyl dipeptidase activity of the high-speed supernatant prepared from a homogenate in the presence of different inhibitor concentrations using the assay described in the materials and methods section. Data is expressed relative to uninhibited activity.

The toxicity of ACE inhibitors to larval instars of Ae. aegypti and An. gambiae

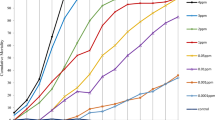

The juvenile part of the mosquito life-cycle involves four larval instars (L1, L2, L3 and L4) of rapid growth and three larval moults before the transition to a pupa and complete metamorphosis to the adult. We investigated the effect of captopril and fosinopril on the survival of three larval stages (L1, L2 and L3) of both Ae. aegypti and An. gambiae by adding the chemicals to the water environment with the larval food followed by assessing mortality after 24, 48 and 72 h. High mortality was recorded for three larval instars (L1, L2 and L3) of Ae. aegypti after the first 24 h of treatment with captopril and by 48 h essentially all L1 and L2 insects were dead (Fig. 4a). The L3 instars were slightly more resistant to captopril, nevertheless by 72 h mortality of these insects had reached around 90%. Very similar results were obtained when L1 and L2 larvae of An. gambiae were treated in an identical manner with captopril (Fig. 4b). The L3 insects were, however, more resistant compared to Ae. aegypti at the same stage of development. Even after 72 h only 10% of the An. gambiae L3 larvae had succumbed to the inhibitor.

Larvae of Ae. aegypti (a and c) and An. gambiae (b and d) were placed in water containing food with either 5 mM captopril (a and b) or 5 mM fosinopril (c and d). Mortality was assessed every 24 h. In the absence of inhibitor all larvae survived and successfully developed into pupae. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 6).

High levels of larval mortality were also recorded for Ae. aegypti treated with fosinopril (Fig. 4c). L1 larvae however appeared to be more resistant compared to the other two instars even after 72 h of treatment, which might reflect a lower metabolic conversion of the pro-drug to the active inhibitor fosinoprilat. On the other hand fosinopril showed high levels of toxicity to all three instars of An. gambiae with over 80% mortality within 24 h and over 95% mortality by 48 h of treatment (Fig. 4d).

We have shown previously that ACE inhibitors fed to adult mosquitoes can have profound effects on female fecundity, suggesting that the mosquito peptidyl dipeptidase is a potential target for the development of novel mosquito control chemicals32,35,40. We have now provided data supporting this view from a study of the effects of ACE inhibitors on the development and survival of larval instars of both Ae. aegypti and An. gambiae. Captopril was one of the first generation of orally active ACE inhibitors and is also the smallest, interacting with only two enzyme sub-sites (S1′ and S2′). These sub-sites have been labelled based around the peptide bond that is cleaved such that the pockets that bind the dipeptide that is released by the enzyme are labelled S1′ and S2′ sub-sites, and the dipeptide itself is labelled P1′ and P2′. The rest of the peptide is labelled P1, P2, etc, which bind in subsites S1, S2, etc, with the peptide being cleaved between residues P1 and P1′. Key to the design of captopril was the inclusion of a sulfhydryl group that interacts with the active site zinc. Other ACE inhibitors can be of a larger design enabling interaction with more than two enzyme sub-sites and may have a different zinc-binding ligand. In the case of fosinoprilat, a hydroxyphosphinyl group interacts with the zinc and this larger molecule binds at three sub-sites (S1, S1′ and S2′) of the enzyme. It is possible that off-target interactions are responsible or contribute to the toxicity observed in this study, however the fact that two ACE inhibitors from different chemical classes show similar toxic effects suggests that mosquito ACE is indeed the likely primary target. The concentration of inhibitor required for toxicity is much higher than the in vitro potency as inhibitors of the larval ACE, indicating some limited availability of the chemicals to the in vivo enzyme. We expect that the water soluble inhibitors are taken up orally with the food rather than through the cuticle. The mosquito larvae feed by filtering out organic particulate matter from the water, a mode of feeding that will limit ingestion of the inhibitors via the oral route. The pro-drug fosinopril has greater hydrophobicity to improve bioavailability and undergoes metabolic de-esterification to fosinoprilat, the active inhibitor. These chemical properties and the requirement that fosinopril undergoes metabolic activation are likely to be important factors in determining the toxicity of the inhibitor to mosquito larvae.

We tested BPP-12b, a member of the BPP family of peptides originally isolated from the venom of the pit viper, Bothrops jararaca, as an inhibitor of mosquito peptidyl dipeptidase and showed that the proline-rich peptide was a powerful natural inhibitor of the activity in both species. The presence of the Pro-Pro sequence at the C-terminus and a pyroglutamate at the N-terminus protects these peptides from metabolic degradation by exo-peptidases7,42. TMOF is a mosquito peptide isolated from the ovaries of adult Ae. aegypti that is also proline rich and therefore it was not surprising that it too inhibits mosquito larval peptidase activity, albeit with reduced potency relative to BPP-12b. TMOF is involved in regulating egg development and blood digestion following a blood meal43. It appears to work by inhibiting the biosynthesis of midgut trypsin and not by inhibition of the protease activity41. TMOF also inhibits trypsin biosynthesis in larval instars and has been used as a larvicide against Ae. aegypti. It is most effective when used in combination with δ-endotoxins from Bacillus thuringiensis44. TMOF is not a particularly potent inhibitor of larval mosquito ACE, nevertheless this inhibition might contribute in a minor way to the toxicity against Ae. aegypti larvae.

The insect ACE gene family has expanded greatly in mosquitoes to nine (AnoACEs 1–9) and there is evidence that four An. gambiae genes (AnoACE2, AnoACE3, AnoACE7 and AnoACE9) are expressed in larval stages. AnoACE7 and AnoACE9 are predicted to have a C-terminal hydrophobic sequence that can form a membrane anchor45. Since the majority of the peptidyl dipeptidase activity in homogenates of larvae is soluble in nature, it seems likely that the activity results from expression of one or both of AnoACE2 and AnoACE3. Homology models for AnoACE2 and AnoACE3 were prepared using SWISS-MODEL46,47,48 with the crystal structure of Drosophila melanogaster ACE homologue (also known as AnCE) (PDB code 2 × 8Y)) used as the template (Fig. 5)49.

tACE is shown in orange, AnCE in purple, AnoACE2 in blue and AnoACE3 in green. The captopril ligands are shown as spheres. The figure was generated using Pymol59.

Our extensive knowledge from high resolution structural studies on how inhibitors interact with both the N- and C-domains of human ACE and insect ACE25,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58 has revealed the molecular basis of binding features of the inhibitors and highlights differences in the inhibitor-enzyme interaction of insect ACE compared with the active sites of the human enzyme. Using the AnoACE homology models and amino acid sequence alignment, it is possible to compare different ACE proteins to look for residue and environment differences in both AnoACE2 and AnoACE3, which could be targeted to create specific inhibitors against these enzymes. Therefore the protein residues forming the binding sub-sites (S2′, S1′ S1 and S2) for the side chains of the region of the peptide (P2′, P1′, P1 and P2) spanning the catalytic site were compared between the different ACE proteins (Table 2). This shows that there are some residues in all four sub-sites that are conserved between human testicular ACE (tACE), which corresponds to the C-domain of human somatic ACE, and the insect ACEs (AnCE, AnoACE2 and AnoACE3). These are residues that could be targeted to increase potency of inhibitors as they are likely to be important in ligand binding, but this will not enhance specificity for AnoACE2 or AnoACE3. There are some residues in tACE that are conserved in either one, or both of the AnoACE proteins, but not in AnCE. These residues would be interesting to target for developing AnCE specific inhibitors. There are also some residues which are identical between AnCE and one, or both of the AnoACE proteins, but not tACE. This provides information for developing a broader insect specific inhibitor. Of particular interest to this study, some residues are unique to either one or both of the AnoACE proteins, and targeting these differences are the most likely route for the development of AnoACE2 and AnoACE3 specific inhibitors. These variations of the sub-sites have already been shown to give rise to different substrate and inhibitor specificities between the different ACE homologues. For example, differences in the S2 sub-site between the N- and C-domains of human somatic ACE have been identified as the cause of certain substrate and inhibitor specificity differences. In particular the substitution of F391 in the C-domain, to Y369 in the N-domain, has been attributed to C-domain selectivity of RXPA380 (see recent review ref. 25). Both AnoACE2 and AnoACE3 also have a tyrosine in this position, but in addition AnoACE2 has another potentially significant change in the S2 sub-site with G403 replacing E403 of tACE (Table 2). This suggests that perhaps the S2 sub-site maybe important for creating an AnoACE2 specific inhibitor, which not only lacks the charge of the E403 found in tACE, but also has a larger binding pocket due to significantly smaller glycine residue.

There are additional notable differences between the AnoACE homologues and human tACE in the S2′ sub-site, and these include changes in size, shape and charge of the side-chains involved. These differences will cause a variation in the size, shape and localised charge of this sub-site between the different proteins, highlighted by the variations shown on the inner protein surface of this void (Fig. 6). Therefore the S2′ sub-site would be of particular interest for AnoACE specific inhibition. Additional non-conserved amino acid substitutions are found in the S1 and S1′ sub-sites. Although less than observed in the S2′ sub-site, they could still result in significant charge changes at the binding site that will in turn influence inhibitor binding.

Surface representation looking into the S1’ and S2’ sub-sites cavity of (a) human tACE-captopril complex, (b) AnCE-captopril complex, (c) AnoACE2 model and (d) AnoACE3 model. The surface is coloured based on atom type (nitrogen in blue, oxygen in red and carbon in beige) and captopril ligands are shown as sticks. Selected residues are labelled to highlight differences between proteins. The figure was generated using CCP4mg60.

This level of detail makes AnoACE an attractive target for applying structure-based drug design to developing potent and, importantly, highly selective inhibitors which could be used as insecticides. These compounds would need to be presented to the larvae of Ae. aegypti and An. gambiae in a particulate form to maximise oral activity in these filter feeders.

Methods

Chemicals

Fosinopril was purchased from Generon Ltd., Maidenhead, Berkshire, U.K. TMOF and BPP-12b was purchased from Biomatik USA, LLC, Wilmington, Delaware, USA. All other ACE inhibitors were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Company Ltd., Poole, Dorset, U.K. The ACE substrate Abz-Phe-Arg-Lys(Dnp)-Pro-OH (Abz-FRK(Dnp)-P) was from Enzo Life Sciences (UK) Ltd, Exeter, U.K.

Mosquito culture

Ae. aegypti (Jinjang, Kuala Lumpur strain) and An. gambiae (Kisumu, Kenya strain) were reared in laboratory insectaries and using standard culture methods at the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia and the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, respectively.

Preparation of mosquito enzyme

Larvae (15, 3rd instar) were washed in distilled water 5 times for 10 minutes and final wash for 1 hour at room temperature before storage at −20 °C until required. Homogenate was prepared using a glass homogeniser (Jencons, East Grinstead, U.K.), containing 0.5 ml of 100 mM HEPES buffer pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl and 10 μM ZnCl2, and 20 up and down strokes of the pestle. A soluble fraction was prepared from the homogenate using a Beckman Optima™ MAX bench-top ultracentrifuge and TLA110 rotor (Beckman Instruments Inc, Palo Alto, Ca, U.S.A.) operating at 55,000 g (4 °C) for 1 h. Aliquots of the homogenate were taken prior to centrifugation to determine the relative distribution of the peptidase activity before and after centrifugation.

Assay of peptidyl dipeptidase activity

Rates of hydrolysis of the quenched fluorogenic substrate Abz-FRK(Dnp)-P by Ae. aegypti and An. gambiae enzymes were performed at 20 °C in 96-well black plastic plates (Corning Life Sciences, High Wycombe, U.K.) using a FLUOstar Omega (BMG LABTECH GmbH, Offenburg, Germany) with λex at 340 nm and λem set at 430 nm). The reaction was started by adding 1 μl of 5 mM Abz-FRK(Dnp)-P in dimethyl sulfoxide) to the enzyme in 200 μl of 100 mM HEPES buffer pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl and 10 μM ZnCl2. For studying the effect of ACE inhibitors, enzyme was pre-incubated with inhibitor for 10 min prior to the addition of substrate.

Larvicidal activity of ACE inhibitors on Ae. aegypti and An. gambiae larvae

Larvicidal testing was performed in 24-well plastic plates (Becton Dickinson Labware, NJ, USA) using 20 Ae. aegypti and An. gambiae larvae of each L1, L2 and L3 stage in distilled water. Inhibitors dissolved in water were added separately to each well containing larvae to give a final concentration of 5 mM with Brewer’s yeast as the food source. Natural mortality was assessed by carrying out a parallel study with the same volume of water and number of larvae in the absence of ACE inhibitor. Mortality in each well was recorded after 24, 48 and 72 h of exposure.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Abu Hasan, Z.-I. et al. The toxicity of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors to larvae of the disease vectors Aedes aegypti and Anopheles gambiae. Sci. Rep. 7, 45409; doi: 10.1038/srep45409 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Johansson, M. A., Dominici, F. & Glass, G. E. Local and global effects of climate on dengue transmission in Puerto Rico. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 3, e382, doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000382 (2009).

Haddow, A. D. et al. Genetic characterization of Zika virus strains: geographic expansion of the Asian lineage. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6, e1477, doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001477 (2012).

Enayati, A. & Hemingway, J. Malaria Management: Past, Present, and Future. Annual Review of Entomology 55, 569–591, doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085423 (2010).

Hemingway, J. The role of vector control in stopping the transmission of malaria: threats and opportunities. Philos T R Soc B 369, doi: Artn 2013043110.1098/Rstb.2013.0431 (2014).

Thomsen, E. K. et al. Underpinning sustainable vector control through informed insecticide resistance management. PLoS One 9, e99822, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099822 (2014).

Ranson, H. & Lissenden, N. Insecticide Resistance in African Anopheles Mosquitoes: A Worsening Situation that Needs Urgent Action to Maintain Malaria Control. Trends Parasitol 32, 187–196, doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2015.11.010 (2016).

Soffer, R. L. Angiotensin-converting enzyme and the regulation of vasoactive peptides. Annual Review of Biochemistry 45, 73–94 (1976).

Erdos, E. G. & Skidgel, R. A. The angiotensin I-converting enzyme. Lab Invest 56, 345–348 (1987).

Corvol, P., Michaud, A., Soubrier, F. & Williams, T. A. Recent Advances In Knowledge Of the Structure and Function Of the Angiotensin-I Converting-Enzyme. J. Hypertension 13 , S 3–S 10 (1995).

Cushman, D. W., Cheung, H. S., Sabo, E. F. & Ondetti, M. A. Design of potent competitive inhibitors of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Carboxyalkanoyl and mercaptoalkanoyl amino acids. Biochemistry 16, 5484–5491 (1977).

Ondetti, M. A. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. An overview. Hypertension 18, III134–135 (1991).

Acharya, K. R., Sturrock, E. D., Riordan, J. F. & Ehlers, M. R. Ace revisited: a new target for structure-based drug design. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2, 891–902 (2003).

Ferreira, S. H., Greene, L. J., Alabaste, V. A., Bakhle, Y. S. & Vane, J. R. Activity of Various Fractions of Bradykinin Potentiating Factor against Angiotensin-I Converting Enzyme. Nature 225, 379, doi: 10.1038/225379a0 (1970).

Cushman, D. W. & Ondetti, M. A. History of the design of captopril and related inhibitors of angiotensin converting enzyme. Hypertension 17, 589–592 (1991).

Camargo, A. C. M., Ianzer, D., Guerreiro, J. R. & Serrano, S. M. T. Bradykinin-potentiating peptides: Beyond captopril. Toxicon 59, 516–523, doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2011.07.013 (2012).

Lamango, N. S., Nachman, R. J., Hayes, T. K., Strey, A. & Isaac, R. E. Hydrolysis of insect neuropeptides by an angiotensin-converting enzyme from the housefly, Musca domestica . Peptides 18, 47–52 (1997).

Lamango, N. S., Sajid, M. & Isaac, R. E. The endopeptidase activity and the activation by Cl- of angiotensin- converting enzyme is evolutionarily conserved: purification and properties of an an angiotensin-converting enzyme from the housefly, Musca domestica. Biochem J 314, 639–646 (1996).

Siviter, R. J. et al. Peptidyl dipeptidases (Ance and Acer) of Drosophila melanogaster: major differences in the substrate specificity of two homologs of human angiotensin I-converting enzyme. Peptides 23, 2025–2034 (2002).

Vandingenen, A. et al. Isolation and characterization of an angiotensin converting enzyme substrate from vitellogenic ovaries of Neobellieria bullata . Peptides 23, 1853–1863 (2002).

Hens, K. et al. Characterization of four substrates emphasizes kinetic similarity between insect and human C-domain angiotensin-converting enzyme. Eur J Biochem 269, 3522–3530 (2002).

Isaac, R. E. & Shirras, A. D. Peptidyl-Dipeptidase A (Invertebrate). Handbook of Proteolytic Enzymes, Vols 1 and 2, 3rd Edition 494–498, doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-382219-2.00099-5 (2013).

Cornell, M. J. et al. Cloning and expression of an evolutionary conserved single-domain angiotensin converting enzyme from Drosophila melanogaster . J Biol Chem 270, 13613–13619 (1995).

Williams, T. A. et al. Drosophila melanogaster angiotensin I-converting enzyme expressed in Pichia pastoris resembles the C domain of the mammalian homologue and does not require glycosylation for secretion and enzymic activity. Biochem. J. 318, 125–131 (1996).

Lamango, N. S., Sajid, M. & Isaac, R. E. Purification and properties of an angiotensin- converting enzyme from the housefly, Musca domestica. Biochem. J. 314, 639–646 (1996).

Harrison, C. & Acharya, K. R. ACE for all - a molecular perspective. J Cell Commun Signal 8, 195–210, doi: 10.1007/s12079-014-0236-8 (2014).

Chintapalli, V. R., Wang, J. & Dow, J. A. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nat Genet 39, 715–720, doi: ng2049 [pii] 10.1038/ng2049 (2007).

Rylett, C. M., Walker, M. J., Howell, G. J., Shirras, A. D. & Isaac, R. E. Male accessory glands of Drosophila melanogaster make a secreted angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ANCE), suggesting a role for the peptide-processing enzyme in seminal fluid. J Exp Biol 210, 3601–3606 (2007).

Wijffels, G. et al. Cloning and characterisation of angiotensin-converting enzyme from the dipteran species, Haematobia irritans exigua, and its expression in the maturing male reproductive system. Eur J Biochem 237, 414–423 (1996).

Ekbote, U., Coates, D. & Isaac, R. E. A mosquito (Anopheles stephensi) angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE) is induced by a blood meal and accumulates in the developing ovary. FEBS Lett 455, 219–222 (1999).

Ekbote, U. V., Weaver, R. J. & Isaac, R. E. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE) activity of the tomato moth, Lacanobia oleracea: changes in levels of activity during development and after copulation suggest roles during metamorphosis and reproduction. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 33, 989–998 (2003).

Vandingenen, A. et al. Captopril, a specific inhibitor of angiotensin converting enzyme, enhances both trypsin and vitellogenin titers in the grey fleshfly Neobellieria bullata . Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 47, 161–167 (2001).

Ekbote, U., Looker, M. & Isaac, R. E. ACE inhibitors reduce fecundity in the mosquito, Anopheles stephensi . Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol 134, 593–598 (2003).

Macours, N. et al. Isolation of angiotensin converting enzyme from the testes of Locusta migratoria (Orthoptera). European Journal of Entomology 100, 467–474 (2003).

Vercruysse, L. et al. The angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor captopril reduces oviposition and ecdysteroid levels in Lepidoptera. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 57, 123–132 (2004).

Isaac, R. E. et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme as a target for the development of novel insect growth regulators. Peptides 28, 153–162 (2007).

Xu, J. J., Baulding, J. & Palli, S. R. Proteomics of Tribolium castaneum seminal fluid proteins: Identification of an angiotensin-converting enzyme as a key player in regulation of reproduction. J Proteomics 78, 83–93, doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.11.011 (2013).

Basso, N. et al. Protective effect of long-term angiotensin II inhibition. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293, H1351–1358, doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00393.2007 (2007).

Kumar, S., Dietrich, N. & Kornfeld, K. Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitor Extends Caenorhabditis elegans Life Span. PLoS Genet 12, e1005866, doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005866 (2016).

Lemeire, E., Borovsky, D., Van Camp, J. & Smagghe, G. Effect of Ace Inhibitors and TMOF on Growth, Development, and Trypsin Activity of Larval Spodoptera littoralis. Archives of Insect Biochemistry and Physiology 69, 199–208, doi: 10.1002/Arch.20270 (2008).

Isaac, R. E., Ekbote, U., Coates, D. & Shirras, A. D. Insect angiotensin-converting enzyme. A processing enzyme with broad substrate specificity and a role in reproduction. Ann N Y Acad Sci 897, 342–347 (1999).

Borovsky, D. Trypsin-modulating oostatic factor: a potential new larvicide for mosquito control. Journal of Experimental Biology 206, 3869–3875, doi: 10.1242/Jeb.00602 (2003).

Hayashi, M. A. & Camargo, A. C. The Bradykinin-potentiating peptides from venom gland and brain of Bothrops jararaca contain highly site specific inhibitors of the somatic angiotensin-converting enzyme. Toxicon 45, 1163–1170, doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.02.017 (2005).

Borovsky, D., Carlson, D. A., Griffin, P. R., Shabanowitz, J. & Hunt, D. F. Mosquito oostatic factor: a novel decapeptide modulating trypsin-like enzyme biosynthesis in the midgut. Faseb J 4, 3015–3020 (1990).

Borovsky, D. et al. Control of mosquito larvae with TMOF and 60 kDa Cry-4Aa expressed in Pichia pastoris . Pesticdes 1–4, 5–15 (2011).

Burnham, S., Smith, J. A., Lee, A. J., Isaac, R. E. & Shirras, A. D. The angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) gene family of Anopheles gambiae. BMC Genomics 6, 172, doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-172 (2005).

Arnold, K., Bordoli, L., Kopp, J. & Schwede, T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics 22, 195–201, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770 (2006).

Bordoli, L. et al. Protein structure homology modeling using SWISS-MODEL workspace. Nature Protocols 4, 1–13, doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.197 (2009).

Biasini, M. et al. SWISS-MODEL: modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Research 42, W252–W258, doi: 10.1093/nar/gku340 (2014).

Akif, M. et al. High-Resolution Crystal Structures of Drosophila melanogaster Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme in Complex with Novel Inhibitors and Antihypertensive Drugs. J Mol Biol, doi: S0022-2836(10)00503-6 [pii]10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.024 (2010).

Akif, M. et al. Crystal structure of a phosphonotripeptide K-26 in complex with angiotensin converting enzyme homologue (AnCE) from Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 398, 532–536, doi: S0006-291X(10)01253-2 [pii]10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.113 (2010).

Masuyer, G., Schwager, S. L. U., Sturrock, E. D., Isaac, R. E. & Acharya, K. R. Molecular recognition and regulation of human angiotensin-I converting enzyme (ACE) activity by natural inhibitory peptides. Sci Rep-Uk 2, doi: 10.1038/Srep00717 (2012).

Akif, M. et al. Novel mechanism of inhibition of human angiotensin-I-converting enzyme (ACE) by a highly specific phosphinic tripeptide. Biochem J 436, 53–59, doi: 10.1042/BJ20102123 (2011).

Anthony, C. S. et al. The N domain of human angiotensin-I converting enzyme: the role of N-glycosylation and the crystal structure in complex with an N domain specific phosphinic inhibitor RXP407. J Biol Chem 285, 3568–3593, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.167866 (2010).

Corradi, H. R., Schwager, S. L. U., Nchinda, A. T., Sturrock, E. D. & Acharya, K. R. Crystal structure of the N domain of human somatic angiotensin I-converting enzyme provides a structural basis for domain-specific inhibitor design. Journal of Molecular Biology 357, 964–974, doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.048 (2006).

Corradi, H. R. et al. The structure of testis angiotensin-converting enzyme in complex with the C domain-specific inhibitor RXPA380. Biochemistry 46, 5473–5478, doi: 10.1021/bi700275e (2007).

Natesh, R., Schwager, S. L., Evans, H. R., Sturrock, E. D. & Acharya, K. R. Structural details on the binding of antihypertensive drugs captopril and enalaprilat to human testicular angiotensin I-converting enzyme. Biochemistry 43, 8718–8724 (2004).

Natesh, R., Schwager, S. L., Sturrock, E. D. & Acharya, K. R. Crystal structure of the human angiotensin-converting enzyme-lisinopril complex. Nature 421, 551–554 (2003).

Houard, X. et al. The Drosophila melanogaster-related angiotensin-I-converting enzymes Acer and Ance-distinct enzymic characteristics and alternative expression during pupal development. Eur J Biochem 257, 599–606 (1998).

The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System Version 1.8 Schrödinger, LLC.

McNicholas, S., Potterton, E., Wilson, K. S. & Noble, M. E. M. Presenting your structures: the CCP4mg molecular-graphics software. Acta Crystallogr D 67, 386–394, doi: 10.1107/S0907444911007281 (2011).

Acknowledgements

Z.I.A.H. was in receipt of a Ph.D. studentship award from the Malaysia Ministry of Higher Education. We acknowledge support of the Liverpool Insect Testing Establishment in assisting with the bioassays.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.I.A.H., K.R.A. and R.E.I. conceived the study and designed the experiments, H.W. performed the toxicity tests on An. gambiae and N.M.I. and H.O. conducted the study on Ae. aegypti. G.C. performed the molecular modelling study and Z.I.A.H., K.R.A. and R.E.I. analysed the data and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Abu Hasan, Z’., Williams, H., Ismail, N. et al. The toxicity of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors to larvae of the disease vectors Aedes aegypti and Anopheles gambiae. Sci Rep 7, 45409 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45409

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45409

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.