Abstract

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) and Takayasu’s arteritis (TAK) are major forms of large-vessel vasculitis (LVV) that share clinical features. To evaluate their genetic similarities, we analysed Immunochip genotyping data from 1,434 LVV patients and 3,814 unaffected controls. Genetic pleiotropy was also estimated. The HLA region harboured the main disease-specific associations. GCA was mostly associated with class II genes (HLA-DRB1/HLA-DQA1) whereas TAK was mostly associated with class I genes (HLA-B/MICA). Both the statistical significance and effect size of the HLA signals were considerably reduced in the cross-disease meta-analysis in comparison with the analysis of GCA and TAK separately. Consequently, no significant genetic correlation between these two diseases was observed when HLA variants were tested. Outside the HLA region, only one polymorphism located nearby the IL12B gene surpassed the study-wide significance threshold in the meta-analysis of the discovery datasets (rs755374, P = 7.54E-07; ORGCA = 1.19, ORTAK = 1.50). This marker was confirmed as novel GCA risk factor using four additional cohorts (PGCA = 5.52E-04, ORGCA = 1.16). Taken together, our results provide evidence of strong genetic differences between GCA and TAK in the HLA. Outside this region, common susceptibility factors were suggested, especially within the IL12B locus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vasculitides represent a heterogeneous group of complex disorders characterised by chronic inflammatory lesions of the blood vessels. Although the pathogenesis of vasculitides is far from being completely understood, cumulating data clearly suggest that both the innate and adaptive responses contribute to their development and progression1. Vasculitides show a large spectrum of clinical manifestations that depend on the affected blood vessel. In this regard, the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference proposed a nomenclature system in which the vasculitides were subdivided into three main groups: small-vessel, medium-vessel, and large-vessel vasculitis (LVV). The LVV group includes giant cell arteritis (GCA) and Takayasu’s arteritis (TAK), which mainly involve arteries of large calibre such as the aorta and its major branches2. These two forms of vasculitis develop predominantly in women, with GCA generally affecting people over 50 years of age in Western countries, especially those of European origin, and TAK affecting younger patients with a higher prevalence in Turkey, Japan, India, and China3,4.

In the last years, the use of novel technologies has produced a substantial advance in the elucidation of the genetic component of LVV5. Large-scale genetic analyses have been recently published separately for both GCA and TAK using the Immunochip platform6,7. The Immunochip has been shown to be one of the most successful platforms to identify immune-related risk variants for a large spectrum of immune-mediated diseases. The use of the same platform in these studies has facilitated the identification of shared aetiopathogenic pathways amongst these disorders, supporting the hypothesis of a common genetic background underlying autoimmunity8.

To contribute to the development of better diagnostic and prognostic markers of LVV, we evaluated the genetic similarities between GCA and TAK by performing an inter-disease meta-analysis of genomic data.

Results

Analysis of the HLA region

The HLA region harboured the main disease-specific associations in our study cohort (Fig. 1). In this context, GCA was mostly associated with class II genes, with the SNP rs9405038 (located between HLA-DRA and HLA-DRB1) representing the lead signal (P = 6.65E-16, OR = 1.60). In contrast, the main associations with TAK were located within the class I subregion, with rs12524487 (located between HLA-B and MHC class I polypeptide-related sequence A; MICA) as the strongest hit (P = 1.92E-16, OR = 3.70). Neither SNP showed even suggestive P-values in the analysis of the other type of vasculitis (TAK: rs9405038, P = 0.010; GCA: rs12524487, P = 0.244). As a consequence, a high heterogeneity (Q < 0.05) was observed across the region. Consequently, a random effects model was used to meta-analyse the HLA data. Although some class I and II markers surpassed the study-wide significance threshold (e.g. class I: rs9263969, P = 3.01E-07, ORGCA = 0.77, ORTAK = 0.77; class II: rs9272105, P = 3.74E-11, ORGCA = 1.38, ORTAK = 1.57), both the number of associations and their effect size was considerably reduced in comparison with the analysis of GCA and TAK separately (Fig. 1, see Supplementary Table S1).

Manhattan plot representation of the results of the HLA region in (A) giant cell arteritis, (B) Takayasu’s arteritis, and (C) the meta-analysis of both forms of vasculitis. The log10 of the P values are plotted against their physical chromosomal position. A red/green color gradient was used to represent the effect size of each analysed polymorphism (red for risk and green for protection). The red line represents the study-wide level of significance (P < 1.13E-06). HLA class I and II subregions are highlighted in grey.

Analysis of the non-HLA region

Outside the HLA region, only one variant surpassed the study-wide significance threshold in the overall meta-analysis including both diseases (rs755374, P = 7.54E-07; ORGCA = 1.19, ORTAK = 1.50; Table 1, see Supplementary Figure S1). This SNP is located in an intergenic region at 71 kb 5′ of the interleukin 12B (IL12B) gene (see Supplementary Figure S2).

Other suggestive common susceptibility factors for both diseases that showed trends of association included glutamate ionotropic receptor NMDA type subunit 2 A (GRIN2A; rs1448258, P = 2.69E-06, ORGCA = 1.23, ORTAK = 1.29), G-protein signaling modulator 1 (GPSM1; rs28489139, P = 1.38E-05, ORGCA = 1.27, ORTAK = 1.98), nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS2; rs7406657, P = 2.65E-05, ORGCA = 0.76, ORTAK = 0.88), ASH1 like histone lysine methyltransferase (ASH1L; rs7340058, P = 6.26E-05, ORGCA = 0.61, ORTAK = 0.58), REL proto-oncogene, NF-kB subunit (REL; rs79657074, P = 6.73E-05, ORGCA = 1.32, ORTAK = 1.82), SMG6, nonsense mediated mRNA decay factor (SMG6, rs10852932; P = 6.88E-05, ORGCA = 0.83, ORTAK = 0.80), protein kinase C theta (PRKCQ, rs587198; P = 7.87E-05, ORGCA = 1.20, ORTAK = 1.22), endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 (ERAP1, rs2255637; P = 8.77E-05, ORGCA = 1.18, ORTAK = 1.27), and ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 E3 (UBE2E3, rs7349232; P = 9.84E-05, ORGCA = 1.24, ORTAK = 1.25).

As previously described7, a group of variants in high linkage disequilibrium (LD), located downstream of the proteasome assembly chaperone 1 (PSMG1) gene on chromosome 21q22, also showed evidence of association with TAK in the analyses of each disease separately (lead variant: rs35819975, P = 7.98E-07, OR = 0.62).

Additional analyses of the association of IL12B with large-vessel vasculitis

To further analyse the consistency of the putative shared association with the IL12B variant rs755374, we checked the signal in the remaining cohorts included in the published GCA Immunochip, which comprised 650 additional cases of GCA and 12,491 controls from UK, North America (USA/Canada), Germany, and Norway6 (see Supplementary Table S2). Significant results at the nominal level of significance were observed when these replication cohorts were tested for IL12B rs755374 (P = 4.69E-02, OR = 1.13, 95% CI = 1.01–1.27), as well as when a meta-analysis including all GCA cohorts was performed (P = 5.52E-04, OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.07–1.26). Finally, an overall P = 3.41E-07 was obtained after meta-analysing all the available data for this SNP (including the six GCA cohorts and the two TAK cohorts), with no heterogeneity observed amongst the different ORs (Q = 0.19).

To further understand this common association, we looked for SNPs in high LD (r2 > 0.8) with IL12B rs755374 in the European populations of the 1000 genomes project using the online annotation tool HaploReg v4.1 (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mammals/haploreg/haploreg.php)9. Three markers were identified (rs6871626, rs56167332, and rs4921492), all of them previously associated with other immune-mediated diseases (Table 2). Interestingly, different functional annotations were observed for rs4921492, including enhancer and promoter histone marks (H3K4me1 and H3K4me3, respectively) as well as DNAse hypersensitivity peaks in different immune cell types. Additionally, the associated hit of our study, rs755374, also overlapped with the H3K4me1 enhancer histone mark in primary B cells from peripheral blood. Furthermore, the “genome-wide repository of associations between SNPs and phenotypes”10 showed 589 expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) hits for rs6871626 in normal prepouch ileum, including key genes of the immune response like CD40, IL2RA, IL6R, IL10RA, IL12RB1, and different HLA class II molecules.

Genetic correlation between giant cell arteritis and Takayasu’s arteritis

We estimated the whole genetic overlap between these two forms of LVV using a bivariate REML analysis on the Immunochip data (Table 3). A significant correlation was suggested only outside the HLA region (rG = 0.500, SE = 0.194, P = 5.00E-03) but not inside the region (rG = 0.012, SE = 0.192, P = 0.5). Similar results were obtained when we quantified the correlation by analysing polygenic risk scores on one disease calculated with the ORs of the markers that showed suggestive P-values (P < 1.00E-04) on the other disease (Table 3). GCA cases had a significant enrichment of non-HLA risk alleles for TAK when compared to controls (PGCA = 3.53E-03) and vice-versa (PTAK = 3.60E-02), with no correlation observed within the HLA region (PGCA = 0.27 and PTAK = 0.70).

Discussion

This cross-disease analysis of Immunochip data represents the first interrogation of the genetic overlap between GCA and TAK. Although both conditions are characterised by inflammatory damage of the wall of large arteries2, the patterns of vascular involvement differ somewhat between them. In TAK the most affected vessels correspond with the aorta and its major branches, whereas in GCA the main lesions are usually localised in more peripheral arteries (such as the branches of the external carotid artery) and GCA is sometimes associated with the development of polymyalgia rheumatica11. Despite the evident differences that these two types of LVV show in the clinical manifestations, geographic distributions, and average age of disease onset, their similar histopathological features (with presence of inflammatory infiltrates within the vessel walls and granulomatous lesions12) have raised controversy over whether or not these conditions represent different subtypes of a single disease entity3. Comparative analyses of their genetic components may definitively help to answer this question.

Our results support the existence of a shared portion of the genetic susceptibility between GCA and TAK, but only outside the HLA region. As previously described6, GCA is mostly associated with class II genes (HLA-DRB1/HLA-DQA1), although some less intense class I signals may be also involved in disease predisposition. The opposite is observed in TAK, that is, the peak HLA associations are located within class I (HLA-B/MICA), with lower but still significant signals in class II7,13. The meta-analysis of this genomic region in our study cohorts reduced considerably the statistical significance of the disease-specific associations, thus confirming that distinct HLA haplotypes define each form of LVV. In this sense, GCA can be grouped with vasculitides such as ANCA-associated vasculitis or IgA vasculitis into class II diseases associated with HLA-DRB1 alleles14,15, while TAK and Behçet’s disease would represent archetypal class I diseases7,16.

Despite the similar histological features of GCA and TAK (which may be a consequence of the activation of dendritic cells within the vessel wall3,17), the different genetic architecture between these two diseases within the HLA region may reflect distinctive effects of the initial inflammatory stimuli. In this context, whereas the infiltrates in GCA are mostly composed of CD4+ T cells and macrophages12, infiltrations of CD8+ T cells are characteristic in TAK lesions18, which is in agreement with their specific associations with the HLA class II and I loci, respectively. Indeed, early studies described an increased in vitro cytotoxicity and a direct action of CD8+ T cells on large arteries from TAK patients19.

Regarding the non-HLA region, different relevant genes for the development of autoimmunity processes were suggested as shared risk factors for LVV, including NOS2, ERAP1, REL and PRKQC, which have been associated with psoriasis, Behçet disease, ankylosing spondylitis (AS), and rheumatoid arthritis, amongst others20,21,22. In the case of NOS2, which encodes a nitric oxide (NO) synthase involved in the release of NO during the immune response, previously published genetic evidences supported a role of this gene in GCA pathogenesis23,24.

However, a SNP located 5′ of IL12B, rs755374, represented the most consistent common associated signal between GCA and TAK. IL12B is a well-established risk gene for TAK7,13,25, but this is the first time that it has been implicated in the predisposition of GCA. Although it should be noted that this genetic variant represented a suggestive signal in the original Immunochip of this disease (P = 5.52E-04, OR = 1.16)6. This gene encodes the P40 subunit that is shared between the interleukins IL-12 and IL-23. It has been described that IL-12 induces Th1 differentiation, whereas IL-23 along with IL-1β promote Th-17 differentiation and function26. Consistent with the association with IL12B reported here, previous candidate gene studies have reported genetic associations between GCA and receptors of these cytokines27. Increasing evidence points to Th-1 and Th-17 cells as pivotal players in the development of LVV12,28. Specifically, in GCA, recent studies have shown that these cell types are directly involved in the main immunopathological pathways responsible for the clinical phenotypes of this type of vasculitis29,30,31,32,33,34. Interestingly, blocking of IL-12/23 p40 with ustekinumab resulted in an improvement of symptoms in patients with refractory GCA35.

The associated IL12B SNP is in high LD (r2 > 0.9) with other IL12B variants (rs6871626, rs56167332, and rs4921492) that overlap with different regulatory marks in immune cells (Table 2). One of them, rs6871626, has been recently established as a marker for disease severity in TAK25. These proxies have been previously identified as key susceptibility factors for several immune-mediated diseases, including TAK, inflammatory bowel diseases (both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis), AS, and sarcoidosis, and leprosy7,13,36,37,38,39,40,41.

In summary, through an inter-disease meta-analysis of large scale genotyping data we evaluated the extent of genetic similarities between GCA and TAK. Our results suggest that the genetic architecture of these disorders differs more than expected, especially in the HLA region, considering their similar patterns of histological disease. Nevertheless, common non-HLA associations were suggested, including IL12B. Given that these conditions are often diagnosed after periods of low-level symptoms or even no symptoms, these data may lead to both reliable disease-specific diagnostic molecular markers and more targeted therapies for each form of LVV.

Methods

Study population

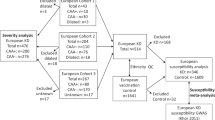

In total, 1,434 patients diagnosed with LVV and 3,814 unaffected controls were analysed. The study cohort comprised the two populations of patients with TAK included in the Immunochip analysis7, one of European ancestry from North America (USA/Canada; 110 TAK cases and 558 unaffected controls) and one from Turkey (327 TAK cases and 481 unaffected controls), as well as two of the six cohorts included in the Immunochip analysis of GCA6, a cohort from Spain (759 GCA cases and 1,505 unaffected controls) and a cohort from Italy (238 GCA cases and 1,270 unaffected controls) (see Supplementary Figure S3). The reason for not including all the available datasets of the Immunochip of GCA was to maintain a balance between the sample sizes of both diseases. All cases were diagnosed following the 1990 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for both TAK and GCA42,43. The main clinical features of the analysed patients were detailed elsewhere6,7. All participants signed a written informed consent before being included in the study, and the procedures were followed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethics Committees on human experimentation of Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (Spain), University of Cantabria (Spain), Hospital Clínic de Barcelona (Spain), University of Parma (Italy), University of Michigan (USA), Marmara University (Turkey), and Istanbul University (Turkey), which provided approval for the study and all experimental protocols.

Quality control and data imputation

To ensure consistency amongst datasets, different standard quality filters were applied to the Immunochip raw data of both diseases in parallel with PLINK v1.0744 prior imputation: single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with cluster separation <0.4, call rates <98%, minor allele frequencies (MAF) <1%, and those deviating from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE; P < 0.001) were excluded; samples with <95% successfully called SNPs, first-degree relatives (identity by descent >0.4), and those showing >4 standard deviations from the cluster centroids of each population using the first ten principal components (PC; estimated using the ancestry markers included in the Immunochip) were also removed. Sex chromosomes were not analysed.

SNP genotype imputation was performed separately for each dataset using IMPUTE v.245 and the 1000 Genome Project Phase III data as reference panel (www.1000genomes.org)46. For that, the SNP map was updated to rs# and build 37 (HG19) using PLINK. Subsequently, chunks of 50,000 Mbp were generated and imputed with a probability threshold of 0.9 for merging genotypes. SNP data were also tightly filtered in PLINK after imputation as follows: call rate <98%, MAF <1%, HWE P < 0.001. A total of 213,188 SNPs were shared amongst the different imputed studies after QC.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were carried out with PLINK and the R-base software under GNU Public license v2. First, each case-control study was tested for association by logistic regression on the best-guess genotypes (>0.9 probability) assuming an additive model and using the ten first PCs and gender as covariates. Next, all studies were meta-analysed with the inverse variance weighted meta-analysis method under a fixed effects models, except for the HLA region that was analysed under a random effects model. Cochran’s Q test was used to measure the heterogeneity of the ORs amongst the different datasets. The threshold for statistical significance in our study was established at 1.13E-06, accordingly with the estimation by the genetic type I error calculator software, which implements a Bonferroni-based validated method to control for type I errors47.

Analysis of the Genetic Pleiotropy

The genetic pleiotropy between GCA and TAK was assessed using both a bivariate and a polygenic risk score (PRS) analysis on Immunochip data, as previously described48. In brief, the genetic correlation (rG) was estimated by GCTA bivariate restricted maximum likelihood (REML) analysis using a genetic relationship matrix, containing data of identity by descent relationship for all pair-wise sets of individuals, and the first ten PCs as covariates. The statistical significance was determined by a likelihood ratio test (LRT). The genetic overlap between both types of vasculitis was also calculated by analysing PRS in one disease predicting risk for the other disease. We obtained for each participant included in the GCA/control cohorts a weighted mean of genotype dosage using the log of the ORs of set of tag SNPs (r2 < 0.20 within 500 kb windows) showing suggestive P-values in the TAK meta-analysis (P < 1.00E-04), and vice versa. We then analysed the difference between the score distribution in case and control subjects (considering the first ten PCs, country of origin, and gender as variables) through a LRT to quantify the relationship between the computed scores and disease status.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Carmona, F. D. et al. Analysis of the common genetic component of large-vessel vasculitides through a meta-Immunochip strategy. Sci. Rep. 7, 43953; doi: 10.1038/srep43953 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

05 April 2017

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

05 April 2017

Scientific Reports 7: Article number: 43953; published online: 09 March 2017; updated: 05 April 2017 In this Article, Javier Martin is incorrectly listed as being affiliated with “Departamento de Genética e Instituto de Biotecnología, Universidad de Granada, Granada 18016, Spain”. The correct affiliation is listed below:

References

Ramirez, G. A., Maugeri, N., Sabbadini, M. G., Rovere-Querini, P. & Manfredi, A. A. Intravascular immunity as a key to systemic vasculitis: a work in progress, gaining momentum. Clinical and experimental immunology 175, 150–166, doi: 10.1111/cei.12223 (2014).

Jennette, J. C. et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis and rheumatism 65, 1–11, doi: 10.1002/art.37715 (2013).

Luqmani, R. Large vessel vasculitides: update for the cardiologist. Current opinion in cardiology 27, 578–584, doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32835895ea (2012).

Romero-Gomez, C. et al. Epidemiological study of primary systemic vasculitides among adults in southern Spain and review of the main epidemiological studies. Clinical and experimental rheumatology 33, S-11-18 (2015).

Carmona, F. D., Martin, J. & Gonzalez-Gay, M. A. Genetics of vasculitis. Current opinion in rheumatology 27, 10–17, doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000124 (2015).

Carmona, F. D. et al. A large-scale genetic analysis reveals a strong contribution of the HLA class II region to giant cell arteritis susceptibility. American journal of human genetics 96, 565–580, doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.02.009 (2015).

Saruhan-Direskeneli, G. et al. Identification of multiple genetic susceptibility loci in Takayasu arteritis. American journal of human genetics 93, 298–305, doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.05.026 (2013).

Parkes, M., Cortes, A., van Heel, D. A. & Brown, M. A. Genetic insights into common pathways and complex relationships among immune-mediated diseases. Nature reviews. Genetics 14, 661–673, doi: 10.1038/nrg3502 (2013).

Ward, L. D. & Kellis, M. HaploReg v4: systematic mining of putative causal variants, cell types, regulators and target genes for human complex traits and disease. Nucleic acids research 44, D877–881, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1340 (2016).

Eicher, J. D. et al. GRASP v2.0: an update on the Genome-Wide Repository of Associations between SNPs and phenotypes. Nucleic acids research 43, D799–804, doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1202 (2015).

Gonzalez-Gay, M. A. et al. Epidemiology of giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica. Arthritis and rheumatism 61, 1454–1461, doi: 10.1002/art.24459 (2009).

Weyand, C. M. & Goronzy, J. J. Immune mechanisms in medium and large-vessel vasculitis. Nature reviews. Rheumatology 9, 731–740, doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.161 (2013).

Terao, C. et al. Two susceptibility loci to Takayasu arteritis reveal a synergistic role of the IL12B and HLA-B regions in a Japanese population. American journal of human genetics 93, 289–297, doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.05.024 (2013).

Lopez-Mejias, R. et al. HLA-DRB1 association with Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Arthritis Rheumatol 67, 823–827, doi: 10.1002/art.38979 (2015).

Lyons, P. A. et al. Genetically distinct subsets within ANCA-associated vasculitis. The New England journal of medicine 367, 214–223, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108735 (2012).

Ortiz-Fernandez, L. et al. Genetic Analysis with the Immunochip Platform in Behcet Disease. Identification of Residues Associated in the HLA Class I Region and New Susceptibility Loci. PloS one 11, e0161305, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161305 (2016).

Krupa, W. M. et al. Trapping of misdirected dendritic cells in the granulomatous lesions of giant cell arteritis. The American journal of pathology 161, 1815–1823, doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64458-6 (2002).

Seko, Y. et al. Perforin-secreting killer cell infiltration and expression of a 65-kD heat-shock protein in aortic tissue of patients with Takayasu’s arteritis. The Journal of clinical investigation 93, 750–758, doi: 10.1172/JCI117029 (1994).

Scott, D. G. et al. Takayasu’s arteritis: a pathogenetic role for cytotoxic T lymphocytes? Clinical rheumatology 5, 517–522 (1986).

Baurecht, H. et al. Genome-wide comparative analysis of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis gives insight into opposing genetic mechanisms. American journal of human genetics 96, 104–120, doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.12.004 (2015).

Kirino, Y. et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies new susceptibility loci for Behcet’s disease and epistasis between HLA-B*51 and ERAP1. Nature genetics 45, 202–207, doi: 10.1038/ng.2520 (2013).

Okada, Y. et al. Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis contributes to biology and drug discovery. Nature 506, 376–381, doi: 10.1038/nature12873 (2014).

Enjuanes, A. et al. Association of NOS2 and potential effect of VEGF, IL6, CCL2 and IL1RN polymorphisms and haplotypes on susceptibility to GCA–a simultaneous study of 130 potentially functional SNPs in 14 candidate genes. Rheumatology (Oxford) 51, 841–851, doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker429 (2012).

Gonzalez-Gay, M. A. et al. Association of a functional inducible nitric oxide synthase promoter variant with susceptibility to biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis. The Journal of rheumatology 32, 2178–2182 (2005).

Matsumura, T. et al. A novel susceptibility locus for Takayasu arteritis in the IL12B region can be a genetic marker of disease severity. Heart and vessels 31, 1016–1019, doi: 10.1007/s00380-015-0661-5 (2016).

Goriely, S., Neurath, M. F. & Goldman, M. How microorganisms tip the balance between interleukin-12 family members. Nature reviews. Immunology 8, 81–86, doi: 10.1038/nri2225 (2008).

Rodriguez-Rodriguez, L. et al. Role of rs1343151 IL23R and rs3790567 IL12RB2 polymorphisms in biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis. The Journal of rheumatology 38, 889–892, doi: 10.3899/jrheum.101046 (2011).

Arnaud, L., Haroche, J., Mathian, A., Gorochov, G. & Amoura, Z. Pathogenesis of Takayasu’s arteritis: a 2011 update. Autoimmunity reviews 11, 61–67, doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.08.001 (2011).

Samson, M. et al. Th1 and Th17 lymphocytes expressing CD161 are implicated in giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica pathogenesis. Arthritis and rheumatism 64, 3788–3798, doi: 10.1002/art.34647 (2012).

Ciccia, F. et al. Difference in the expression of IL-9 and IL-17 correlates with different histological pattern of vascular wall injury in giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 54, 1596–1604, doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kev102 (2015).

Carmona, F. D., Martin, J. & Gonzalez-Gay, M. A. New insights into the pathogenesis of giant cell arteritis and hopes for the clinic. Expert review of clinical immunology 12, 57–66, doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2016.1089173 (2016).

Coit, P., De Lott, L. B., Nan, B., Elner, V. M. & Sawalha, A. H. DNA methylation analysis of the temporal artery microenvironment in giant cell arteritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 75, 1196–1202, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-207116 (2016).

Visvanathan, S. et al. Tissue and serum markers of inflammation during the follow-up of patients with giant-cell arteritis–a prospective longitudinal study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 50, 2061–2070, doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker163 (2011).

Espigol-Frigole, G. et al. Increased IL-17A expression in temporal artery lesions is a predictor of sustained response to glucocorticoid treatment in patients with giant-cell arteritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 72, 1481–1487, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201836 (2013).

Conway, R. et al. Ustekinumab for the treatment of refractory giant cell arteritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 75, 1578–1579, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209351 (2016).

Anderson, C. A. et al. Meta-analysis identifies 29 additional ulcerative colitis risk loci, increasing the number of confirmed associations to 47. Nature genetics 43, 246–252, doi: 10.1038/ng.764 (2011).

Jostins, L. et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 491, 119–124, doi: 10.1038/nature11582 (2012).

Zhang, L. et al. Association Study of IL-12B Polymorphisms Susceptibility with Ankylosing Spondylitis in Mainland Han Population. PloS one 10, e0130982, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130982 (2015).

Liu, H. et al. Identification of IL18RAP/IL18R1 and IL12B as leprosy risk genes demonstrates shared pathogenesis between inflammation and infectious diseases. American journal of human genetics 91, 935–941, doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.09.010 (2012).

Liu, J. Z. et al. Association analyses identify 38 susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease and highlight shared genetic risk across populations. Nature genetics 47, 979–986, doi: 10.1038/ng.3359 (2015).

Fischer, A. et al. Identification of Immune-Relevant Factors Conferring Sarcoidosis Genetic Risk. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 192, 727–736, doi: 10.1164/rccm.201503-0418OC (2015).

Arend, W. P. et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis and rheumatism 33, 1129–1134 (1990).

Hunder, G. G. et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of giant cell arteritis. Arthritis and rheumatism 33, 1122–1128 (1990).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. American journal of human genetics 81, 559–575, doi: 10.1086/519795 (2007).

Howie, B. N., Donnelly, P. & Marchini, J. A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS genetics 5, e1000529, doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000529 (2009).

Auton, A. et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526, 68–74, doi: 10.1038/nature15393 (2015).

Li, M. X., Yeung, J. M., Cherny, S. S. & Sham, P. C. Evaluating the effective numbers of independent tests and significant p-value thresholds in commercial genotyping arrays and public imputation reference datasets. Human genetics 131, 747–756, doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-1118-2 (2012).

Marquez, A. et al. A combined large-scale meta-analysis identifies COG6 as a novel shared risk locus for rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Annals of the rheumatic diseases In Press, 76, 286–294, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209436 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sofia Vargas, Sonia García and Gema Robledo for their excellent technical assistance and all the patients and control donors for their essential collaboration. This work was supported by SAF2012–34435 from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, BIO-1395 from Junta de Andalucía, and RD12/0009/0004 from the RETICS Program (RIER) of Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII). FDC was recipient of a grant from the ‘Ramón y Cajal’ programme of the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (RYC-2014–16458). MCC and JHR are supported by Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (SAF 14/57708R), cofunded by “Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional, Unión Europea, Una manera de hacer Europa” [Instituto de Salud Carlos III and Fondo Europeo de desarrollo regional (FEDER) (PIE 13/00033)]. The Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium has received support from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (U54AR057319), the National Center for Research Resources (U54 RR019497), the Office of Rare Diseases Research, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Science. The VCRC is part of the Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

F.D.C. performed the statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript; F.D.C., J.M., and A.H.S. made substantial contributions to study conception and design as well as to interpretation of data; P.C., G.S.-D., J.H.-R., M.C.C., R.S., S.C., A.V., H.D., P.A.M., L.B., C.S., M.A.G.-G., J.M., and A.H.S. revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content; P.C., G.S.-D., J.H.-R., M.C.C., R.S., S.C., A.V., H.D., P.A.M., L.B., C.S., M.A.G.-G., J.M., A.H.S., and the consortium members were involved in the acquisition of data; all authors approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Carmona, F., Coit, P., Saruhan-Direskeneli, G. et al. Analysis of the common genetic component of large-vessel vasculitides through a meta-Immunochip strategy. Sci Rep 7, 43953 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43953

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43953

This article is cited by

-

Frequency and the effects of spondyloarthritis-spectrum disorders on the clinical course and management of Takayasu arteritis: an observational retrospective study

Clinical Rheumatology (2024)

-

Distinct gene signatures of monocytes and B cells in patients with giant cell arteritis: a longitudinal transcriptome analysis

Arthritis Research & Therapy (2023)

-

Central and Peripheral Nervous System Complications of Vasculitis Syndromes from Pathology to Bedside: Part 2—Peripheral Nervous System

Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports (2023)

-

Presentation and clinical course of pediatric-onset versus adult-onset Takayasu arteritis—a systematic review and meta-analysis

Clinical Rheumatology (2022)

-

Highlights in clinical medicine—Giant cell arteritis, polymyalgia rheumatica and Takayasu’s arteritis: pathogenic links and therapeutic implications

Clinical and Experimental Medicine (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.