Abstract

A series of mono-amide-functionalized pillar[5]arenes with different lengths of N-ω-aminoalkyl groups as the side chain on the rim were designed and synthesized, which all formed pseudo[1]rotaxanes in the crystal state. And these pseudo[1]rotaxanes could be transformed into [1]rotaxanes or open forms in the crystal state. In addition, they were also studied in solution by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mechanically interlocked molecules as a type of interesting and unique molecules, which could be extensively found in nature or artificially synthesized, have been widely applied in the fields of biology and smart materials1,2,3. As one family of basic mechanically interlocked structures, pseudorotaxanes and rotaxanes4,5,6,7 have become a research area of great interest in recent years, because they are able to not only become the fundamental precursors for the preparation of novel supramolecular species, such as catenanes8,9, but also realize some functionality and show the response to external stimuli, which could be the prototypes of simple molecular machines10,11,12. Among the family of various interlocked pseudorotaxanes and rotaxanes, pseudo[1]rotaxane and [1]rotaxanes typically contain the wheel and axle that are connected in one molecule with a fast or slow exchange process between threaded and free forms or with a stable threaded form in solution or solid state13,14,15. In particular, pseudo[1]rotaxanes and [1]rotaxanes can be extensively utilized as molecular machines to show corresponding response to external stimuli due to their reversible conversion behavior16,17. The [1]rotaxanes could be synthesized from the threaded structure of pseudo[1]rotaxanes by the introduction of a stopper unit18 based on the “threading-followed-by-stoppering” strategy19, but [1]rotaxanes cannot efficiently be synthesized by this method or other traditional methods20,21,22,23. Therefore, the highly efficient synthesis of [1]rotaxanes from pseudo[1]rotaxanes is still a challenge.

Pillararenes are a new class of supramolecular hosts after crown ethers, cyclodextrins, calixarenes, and cucurbiturils24,25,26,27,28. The unique tubular structures of pillararenes as one type of supramolecular hosts have been applied in the construction of novel supramolecular polymers, molecular devices, and artificial transmembrane channels, as well as chemical and physical responding materials29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. Among them, pillar[5]arenes have been widely used to fabricate a number of interlocked assemblies37,38,39,40,41,42,43, for example, Huang43 reported a [2]rotaxane based on the pillar[5]arene/imidazolium recognition motif, which showed solvent- and thermo-driven molecular motions, and the [2]rotaxane self-assembled in DMSO to form a supramolecular gel with multiple stimuli-responsiveness. And particularly, various pillar[5]arene-based pseudo[1]rotaxanes with diverse functions have been developed44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52. For examples, Stoddart44 investigated the self-complexing behavior of a monofunctionalized pillar[5]arene derivative containing a viologen moiety. Cao47 reported that pillar[5]arene-based pseudorotaxanes selectively bound dihalogenalkanes in non-polar solvent. Hou46 reported that the amide group on the side-chain of pillar[5]arenetune toward the inner space of cavity by intramolecular H-bonding, leading to the formation of a pseudo[1]rotaxane structure. However, the reported pillar[5]arene-based [1]rotaxane is very limited. For example, Xue51 reported the highly efficient synthesis of one pillar[5]arene-based [1]rotaxane by amidation of monocarboxylic acid-functionalized pillar[5]arene with long chain amine guest in 73% yield. In addition, the systematic investigation of the formation of a series of pillar[5]arene-based pseudo[1]rotaxanes and their corresponding [1]rotaxanes in their crystal state is little known.

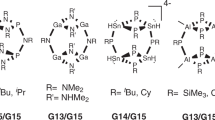

On the basis of our previous work on calixarenes, resorcinarenes53,54, and pillararenes49,50,55,56, herein, we designed and synthesized a series of mono-amide-functionalized pillar[5]arenes 2n (n = 2, 3, 4, 6). All of them could form stable pysedo[1]rotaxanes in the crystal state, and after the treatment of them with salicylaldehyde derivatives as stoppers, a series of corresponding stable [1]rotaxanes 33,4,6, conventional Schiff’s bases, in the crystal state based on the “threading-followed-by-stoppering” strategy and one set of free forms 32m could be achieved (Figs 1 and 2). To the best of our knowledge, it is the first time to systematically investigate a series of pillar[5]arene-based pseudo[1]rotaxanes and their corresponding [1]rotaxanes in the crystal state, in which the formation of [1]rotaxanes was dependent on the axle lengths of their pysedo[1]rotaxanes. In the meantime, [1]rotaxanes could be efficiently synthesized from their pseudo[1]rotaxanes in high yields with 70–79% based on the formation of Schiff’s base with salicylaldehyde derivatives. Besides, the pseudo[1]rotaxanes and their corresponding [1]rotaxanes were also studied in solution by 1H NMR spectroscopy and some of them were studied by theoretical calculations as well.

Results and Discussion

Initially, a series of mono-amide-functionalized pillar[5]arenes 2n (n = 2, 3, 4, 6) were synthesized from monoester copillar[5]arene 1 (Fig. 1). The single crystal structures of monoester copillar[5]arene 1 (Fig. S64 in SI) and pillar[5]arene derivatives 22,3,4,6 were successfully determined by X-ray diffraction method (Fig. 2 and Fig. S65–68 in SI). In Fig. 2, it can be clearly seen that 22,3,4,6 formed a series of stable pseudo[1]rotaxanes in the crystal state, where the pillar[5]arene acted as a wheel and the aminoalkyl side chain acted as an axle. In particular, the crystal structure of 22 with the shortest alkyl chain in the axle (only two CH2 groups) was successfully obtained46. X-ray analysis showed that 22,3,4,6 crystallized in the monoclinic C2/c, monoclinic P21/c, monoclinic P21/n, and orthorhombic P2(1)2(1)2(1) space group, respectively, with one molecule in the asymmetric unit. And the weak C-H··· interactions and C-H···O interactions were observed, which suggested that they played a key role in stabilizing the self-inclusion conformation in the crystal state (Fig. S65–68 in SI). Particularly, in the crystal structure of 22 the presence of N-H···

interactions and C-H···O interactions were observed, which suggested that they played a key role in stabilizing the self-inclusion conformation in the crystal state (Fig. S65–68 in SI). Particularly, in the crystal structure of 22 the presence of N-H··· interactions between the hydrogen atom of the amide groups and the benzene ring of the hosts with the distances of 2.993 Å was observed (Fig. S65 in SI).

interactions between the hydrogen atom of the amide groups and the benzene ring of the hosts with the distances of 2.993 Å was observed (Fig. S65 in SI).

And then, besides the study of their crystal state, pillar[5]arene derivative 22,3,4,6 in solution were also investigated by 1H NMR spectroscopy in the polar solvent DMSO-d6. The 1H NMR spectra also suggested the formation of a series of pseudo[1]rotaxanes of 22,3,4,6 in DMSO-d6(Fig. 3 and Fig. S4–15 in SI), where only one set of peaks were observed and some typical proton signals of aminoalkyl groups appeared in the high magnetic field, indicating the strong shield effect by the cavity of pillar[5]arenes. For examples, the terminal CH2CH2NH2 group in 22 showed three broad peaks at 1.37, 0.20, and −0.97 ppm. The terminal CH2CH2CH2NH2 group in 23 displayed three broad peaks at 0.02, −0.67, and −0.94 ppm. Additionally, the peaks at −0.54, −1.64, and −2.19 ppm from 24 and at −1.04, −1.17, and −1.93 ppm from 26 in the high magnetic field could be observed, which strongly revealed the terminal ω-aminoalkyl group threaded into the cavity of pillar[5]arene to form pseudo[1]rotaxanes in CDCl3. 1H NMR spectra of 22 at various temperature (Fig. S76 in SI) indicated that the characteristic signals of terminal 2-aminoethyl group gradually and slightly shifted to lower magnetic field as the temperature increased. But even at 85 °C, the typical proton peaks still appeared in the high magnetic field. This result indicated the formed pseudo[1]rotaxane 22 in solution is much more stable than its free form. Therefore, the results of the observation of only one set of proton signals in 22,3,4,6 and 1H NMR spectra of 22 at various temperature implied that 22,3,4,6 could possibly be a fast exchange on the NMR time scale in solution.

Subsequently, 22 and 26 with the shortest and longest axle lengths, respectively, were selected to conduct the theoretical calculations for their conformations by DFT theory at M06-2x/6–31G (d, p) level included in GAUSSIAN 09. The relative energy of the structures of pseudo[1]rotaxanes 22 and 26 is much lower than their corresponding free forms with 102.31 kJ/mol and 106.30 kJ/mol, respectively, (Figs S77–79 in SI), which agreed well with the results of the 1H NMR spectroscopy experiments.

And then, after a series of pillar[5]arene-based pysedo[1]rotaxanes in the crystal state and in solution above were achieved, they were reacted with various substituted salicylaldehydes in solution to study the possible formation of their corresponding [1]rotaxanes, where substituted salicylaldehydes were used as stoppers because the size of o-hydroxylphenyl group is big enough so that it cannot thread into or through the cavity of methylated-pillar[5]arenes55,57 as well as the easy connection of terminal amino group of axles and salicylaldehydes based on Schiff’s base formation. Therefore, the condensation of terminal amino groups of pillar[5]arene derivatives 2n with salicylaldehyde and 4-chloro, 4-bromo, 3,5-di(t-butyl) substituted salicylaldehyde derivatives in ethanol resulted in the corresponding pillar[5]arene mono-Schiff’s bases 3nm (n = 2, 3, 4, 6; m represents different substituents on salicylaldehyde group) in high yields with 70–79% (Fig. 1). The structures of synthesized pillar[5]arene derivatives 3nm were fully characterized by IR, HRMS, 1H and 13C NMR spectra (Fig. S16–63 in SI).

The single crystal structures of 32d, 33a-d, 34b, and 36b were succesfully obtained (Fig. 2 and Fig. S69–75 in SI). It is clearly shown from their single crytal structures that 33a-d, 34b, and 36b formed [1]rotaxanes in the crystal state, but 32d clearly showed that the whole side-chain stayed outside of the cavity of pillar[5]arene, leading to the formation of free forms instead of [1]rotaxanes. The reason for this phenomenon is obviously due to the relative short length of the axle (only two CH2 groups) of 22, which was not able to allow the large aryl group to connect it from the cavity. Thus, the amino-group of the side-chain of 22 stayed outside of the cavity and was then reacted with the substituted salicylaldehyde to obtain free form 32d. However, in the crystal state of 33a-d, 34b, and 36b, they have longer axles than 32d, which could play a key role in the formation of [1]rotaxanes. X-ray analysis showed that 33a and 33d crystallized in the monoclinic P21/c, and 33b, 33c, 34b, and 36b crystallized in the triclinic P-1 space group, respectively, with one molecule in the asymmetric unit. And the weak C-H··· interactions and C-H···O interactions were observed similarly as in pysedo[1]rotaxanes (Fig. S70–75 in SI). Therefore, the above results clearly demonstrated the formation of a series of corresponding [1]rotaxanes 33,4,6m from the corresponding pysedo[1]rotaxanes 23,4,6 and free forms 32m in the crystal state as well.

interactions and C-H···O interactions were observed similarly as in pysedo[1]rotaxanes (Fig. S70–75 in SI). Therefore, the above results clearly demonstrated the formation of a series of corresponding [1]rotaxanes 33,4,6m from the corresponding pysedo[1]rotaxanes 23,4,6 and free forms 32m in the crystal state as well.

In the study of their solution state of 3nm, 1H NMR spectra of these compounds (Fig. S16–63 in SI) showed the consistent results with their crystal state. As shown in (Fig. S16–27 in SI), 1H NMR spectra of 32m indicated that the characteristic proton signals at normal positions that were unshielded by the cavity of pillar[5]arene, which suggested that 32m existed in solution as free forms. On the other hand, 1H NMR spectra of 33,4,6m (Fig. S28–63 in SI) displayed that one set of proton signals were observed and some typical proton signals of the bridging propylene, butylene, and hexylene units of axles were located at high magnetic field. For examples, 1H NMR spectra of pillar[5]arene 33a gave three broad singlets at −0.13, −1.77, and −1.95 ppm for the bridging propylene unit. In 1H NMR spectra of pillar[5]arene 36d, five peaks at 0.14, −1.08, −1.10, −1.60, and −2.36 ppm were observed for the bridging hexylene unit. Thus, 1H NMR spectra above revealed that [1]rotaxanes 33,4,6m and free forms 32m in solution were also observed as in their crystal state.

Conclusion

In summary, a series of stable pillar[5]arene-based pseudo[1]rotaxanes 22,3,4,6 and [1]rotaxanes 33,4,6m in crystal state were achieved and symmetrically studied as well as free forms 32m. Their crystal structures suggested that C-H···  interactions, C-H···O, and even N-H··· π interactions helped to stabilize the formation of pseudo[1]rotaxanes, and the formation of [1]rotaxanes depended on the axle length. This work would help us systematically better understand the structures of pseudo[1]rotaxanes and [1]rotaxanes, which would help to design and fabricate more complicated supramolecular systems and develop better functional molecular machines in future.

interactions, C-H···O, and even N-H··· π interactions helped to stabilize the formation of pseudo[1]rotaxanes, and the formation of [1]rotaxanes depended on the axle length. This work would help us systematically better understand the structures of pseudo[1]rotaxanes and [1]rotaxanes, which would help to design and fabricate more complicated supramolecular systems and develop better functional molecular machines in future.

Methods

Materials

All reactions were performed in atmosphere unless noted. All reagents were commercially available and use as supplied without further purification. NMR spectra were collected on either an Agilent DD2 400 MHz spectrometer or a Bruker AV-600 MHz spectrometer with internal standard tetramethylsilane (TMS) and signals as internal references, and the chemical shifts (δ) were expressed in ppm. High-resolution Mass (ESI) spectra were obtained with Bruker Micro-TOF spectrometer. The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) samples were prepared as thin films on KBr plates, and spectra were recorded on a Bruker Tensor 27 spectrometer and are reported in terms of frequency of absorption (cm−1). X-ray data were collected on a Bruker Smart APEX-2 CCD diffractometer.

Synthesis of monoester copillar[5]arene 1

In an atmosphere of nitrogen, a solution of 1,4-dimethoxybenzene (36.2 mmol, 5.00 g), methyl 2-(4-butoxyphenoxy)acetate (9.05 mmol, 2.15 g) and paraforaldehyde (45.25 mmol, 1.36 g) in 1,2-dichloroethane (100 mL) was cooled with ice-bath for about half hour. The ether solution of boron trifluoride (45.25 mmol, 6.42 g) was added in dropwise in half hour. Then, the mixture was stirred at room temperature for five hours. To this solution was added methanol (50 mL). The obtained solution was concentrated and methylene dichloride (50 mL) was added. The solution was washed with 10% sodium bicarbonate solution twice and with water several times. After separation, the organic layer was concentrated and subjected to column chromatography with a mixture of light petroleum and methylene dichloride (v/v = 1:4) as eluate to give the pure product 1 in 29% and 1,4-dimethyl pillar[5]arene in about 10% as white solid for analysis.

Synthesis of 22,3,4,6

A suspension of monoester copillar[5]arene 1 (2.0 mmol, 1.70 g) and excess of α,ω-diaminoalkanes (80 mmol) in ethanol (20 mL) was refluxed for 8 hours. After cooling, the resulting precipitate was collected by filtration and washed with cold ethanol to give the white solid for analysis.

Synthesis of 32a-d, 33a-d, 34a-d, 36a-d

A suspension of 2n (n = 2, 3, 4, 6) (0.23 mmol) and salicylaldehyde or its derivatives (0.33 mmol) in ethanol (20 mL) was refluxed for 4 hours. After cooling, the resulting precipitate was collected by filtration and washed with cold ethanol to give the white solid.

Computational methods

Density functional theory M06-2X functional with 6–31G (d, p) basis set was used. All structures were fully optimized without any symmetry constraints, and vibrational frequency analyses were then carried out at the same theoretical level to confirm whether the optimized geometries were the true minimum energy structures. All calculations were performed using GAUSSIAN 09 software package. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed in solvents of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). A cubic simulation box containing one self-inclusion molecule obtained from theoretical calculations and 500 solvent molecules were constructed using the Universal force field (UFF). UFF is a molecular mechanics force field designed to model the entire periodic table. It has been successfully applied to organic molecules, metallic complexes, and main group compounds. The Edwald summation method was used with a non-bonded interaction cutoff set to 1.25 nm. The MD simulations were performed in the NPT ensemble at 298.15 K and 0.10 MPa using the Berendsen temperature control method with a time step of 1 fs. The trajectory was recorded at 5 ps intervals thus resulting in 1000 frames for the 5 ns simulation. For the whole simulation procedure the software package Materials Studio (6.0) was applied.

Additional Information

Accession Codes: Single crystal data for compounds 1 (CCDC 1424095), 22 (CCDC 1424096), 23 (CCDC 1424097), 24 (CCDC 1438710), 26 (CCDC 1438711) 32d (CCDC 1424098), 33a (CCDC 1424099), 33b (CCDC 1424100), 33c (CCDC 1424101), 33d (CCDC 1424102), 34b (CCDC 1424103), and 36b (CCDC 1424104) have been deposited in the CambridgeCrystallographic DataCenter.

How to cite this article: Han, Y. et al. Formation of a series of stable pillar[5]arene-based pseudo[1]rotaxanes and their [1]rotaxanes in the crystal state. Sci. Rep. 6, 28748; doi: 10.1038/srep28748 (2016).

References

Lohmann, F., Weigandt, J., Valero, J. & Famulok, M. Logic gating by macrocycle displacement using a double-stranded DNA [3]rotaxane shuttle. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 53, 10372–10376 (2014).

Fahrenbach, A. C. et al. Ground-state kinetics of bistable redox-active donor-acceptor mechanically interlocked molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 482–493 (2014).

Fahrenbach, A. C., Bruns, C. J., Cao, D. & Stoddart, J. F. Ground-state thermodynamics of bistable redox-active donor-acceptor mechanically interlocked molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 1581–1592 (2012).

Niu, Z. B. & Gibson, H. W. Polycatenanes. Chem. Rev. 109, 6024–6046 (2009).

Raymo, F. M. & Stoddart, J. F. Interlocked macromolecules. Chem. Rev. 99, 1643–1663 (1999).

Balzani, V., Gómez-López, M. & Stoddart, J. F. Molecular machines. Acc. Chem. Res. 31, 405–414 (1998).

Harada, A., Takashima, Y. & Yamaguchi, H. Cyclodextrin-based supramolecular polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 875–882 (2009).

Cacciapaglia, R. & Mandolini, L. Catalysis by metal-ions in reactions of crown-ether substrates. Chem. Soc. Rev. 22, 221–231 (1993).

Hanni, K. D. & Leigh, D. A. The application of CuAAC ‘click’ chemistry to catenane and rotaxane synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 1240–1251 (2010).

Sauvage, J. P. Transition metal-containing rotaxanes and catenanes in motion: toward molecular machines and motors. Acc. Chem. Res. 31, 611–619 (1998).

Stoddart, J. F. The chemistry of the mechanical bond. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1802–1820 (2009).

Xue, M., Yang, Y., Chi, X., Yan, X. & Huang, F. Development of pseudorotaxanes and rotaxanes: from synthesis to stimuli-responsive motions to applications. Chem. Rev. 115, 7398–7501 (2015).

Lewandowski, B. et al. Sequence-specific peptide synthesis by an artificial small-molecule machine. Science 339, 189–193 (2013).

Ogawa, T., Nakazono, K., Aoki, D., Uchida, S. & Takata, T. Effective approach to cyclic polymer from linear polymer: synthesis and transformation of macromolecular [1]rotaxane. ACS Macro Lett. 4, 343–347 (2015).

Ogawa, T., Usuki, N., Nakazono, K., Koyama, Y. & Takata, T. Linear-cyclic polymer structural transformation and its reversible control using a rational rotaxane strategy. Chem. Commun. 51, 5606–5609 (2015).

Hiratani, K., Kaneyama, M., Nagawa, Y., Koyama, E. & Kanesato, M. Synthesis of [1]rotaxane via covalent bond formation and its unique fluorescent response by energy transfer in the presence of lithium ion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 13568–13569 (2004).

Spence, G. T. & Beer, P. D. Expanding the scope of the anion templated synthesis of interlocked structures. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 571–586 (2013).

Clavel, P. W. C., Fournel-Marotte, K. & Coutrot, F. Synthesis of triazolium-based mono- and tris-branched [1]rotaxanes using a molecular transporter of dibenzo-24-crown-8. Chem. Sci. 6, 4828–4836 (2015).

Cao, J., Fyfe, M. C. T., Stoddart, J. F., Cousins, G. R. L. & Glink, P. T. Molecular shuttles by the protecting group approach. J. Org. Chem. 65, 1937–1946 (2000).

Li, H., Zhang, H., Zhang, Q., Zhang, Q. W. & Qu, D. H. A switchable ferrocene-based [1]rotaxane with an electrochemical signal output. Org. Lett. 14, 5900–5903 (2012).

Xue, Z. & Mayer, M. F. Actuator prototype: capture and release of a self-entangled [1]rotaxane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 3274–3276 (2010).

Li, H. et al. Dual-mode operation of a bistable [1]rotaxane with a fluorescence signal. Org. Lett. 15, 3070–3073 (2013).

Cao, J. et al. INHIBIT logic operations based on light-driven beta-cyclodextrin pseudo[1]rotaxane with room temperature phosphorescence addresses. Chem. Commun. 50, 3224–3226 (2014).

Xue, M., Yang, Y., Chi, X., Zhang, Z. & Huang, F. Pillararenes, a new class of macrocycles for supramolecular chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 1294–1308 (2012).

Cao, D. R. et al. A facile and efficient preparation of pillararenes and a pillarquinone. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 48, 9721–9723 (2009).

Ogoshi, T., Kanai, S., Fujinami, S., Yamagishi, T. A. & Nakamoto, Y. Para-Bridged symmetrical pillar[5]arenes: their Lewis acid catalyzed synthesis and host-guest property. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 5022–5023 (2008).

Zhang, Z. et al. Formation of linear supramolecular polymers that is driven by C-H···π interactions in solution and in the solid state. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 50, 1397–1401 (2011).

Yu, G. et al. Pillar[6]arene-based photoresponsive host-guest complexation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 8711–8717 (2012).

Li, C. et al. Novel neutral guest recognition and interpenetrated complex formation from pillar[5]arenes. Chem. Commun. 47, 11294–11296 (2011).

Li, H. et al. Viologen-mediated assembly of and sensing with carboxylatopillar[5]arene-modified gold nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 1570–1576 (2013).

Xu, J. F., Chen, Y. Z., Wu, L. Z., Tung, C. H. & Yang, Q. Z. Dynamic covalent bond based on reversible photo [4 + 4] cycloaddition of anthracene for construction of double-dynamic polymers. Org. Lett. 15, 6148–6151 (2013).

Hu, X. B. et al. Pillar[n]arenes (n = 8–10) with two cavities: synthesis, structures and complexing properties. Chem. Commun. 48, 10999–11001 (2012).

Li, S. H., Zhang, H. Y., Xu, X. & Liu, Y. Mechanically selflocked chiral gemini-catenanes. Nat. Commun. 6, 7590 (2015).

Li, C. Pillararene-based supramolecular polymers: from molecular recognition to polymeric aggregates. Chem. Commun. 50, 12420–12433 (2014).

Wang, S. et al. The marriage of endo-cavity and exo-wall complexation provides a facile strategy for supramolecular polymerization. Chem. Commun. 51, 3434–3437 (2015).

Chen, H. et al. Biphen[n]arenes. Chem. Sci. 6, 197–202 (2015).

Zhang, Z., Xia, B., Han, C., Yu, Y. & Huang, F. Syntheses of copillar[5]arenes by co-oligomerization of different monomers. Org. Lett. 12, 3285–3287 (2010).

Gao, L., Han, C., Zheng, B., Dong, S. & Huang, F. Formation of a pillar[5]arene-based [3]pseudorotaxane in solution and in the solid state. Chem. Commun. 49, 472–474 (2013).

Han, C., Yu, G., Zheng, B. & Huang, F. Complexation between pillar[5]arenes and a secondary ammonium salt. Org. Lett. 14, 1712–1715 (2012).

Li, C. et al. Complexation of 1,4-bis(pyridinium)butanes by negatively charged carboxylatopillar[5]arene. J. Org. Chem. 76, 8458–8465 (2011).

Li, C. et al. Self-assembly of [2]pseudorotaxanes based on pillar[5]arene and bis(imidazolium) cations. Chem. Commun. 46, 9016–9018 (2010).

Kitajima, K., Ogoshi, T. & Yamagishi, T. Diastereoselective synthesis of a [2]catenane from a pillar[5]arene and a pyridinium derivative. Chem. Commun. 50, 2925–2927 (2014).

Dong, S. Y., Yuan, J. Y. & Huang, F. H. A pillar[5]arene/imidazolium [2]rotaxane: solvent-and thermo-driven molecular motions and supramolecular gel formation. Chem. Sci. 5, 247–252 (2014).

Strutt, N. L., Zhang, H. C., Giesener, M. A., Lei, J. Y. & Stoddart, J. F. A self-complexing and self-assembling pillar[5]arene. Chem. Commun. 48, 1647–1649 (2012).

Ogoshi, T., Demachi, K., Kitajima, K. & Yamagishi, T. Monofunctionalized pillar[5]arenes: synthesis and supramolecular structure. Chem. Commun. 47, 7164–7166 (2011).

Chen, L., Li, Z., Chen, Z. & Hou, J. L. Pillar[5]arenes with an introverted amino group: a hydrogen bonding tuning effect. Org. Biomol. Chem. 11, 248–251 (2013).

Chen, Y. et al. Monoester copillar[5]arenes: synthesis, unusual self-inclusion behavior, and molecular recognition. Chem. Eur. J. 19, 7064–7070 (2013).

Wu, X., Ni, M. F., Xia, W., Hu, X. Y. & Wang, L. Y. A novel dynamic pseudo[1]rotaxane based on a mono-biotin-functionalized pillar[5]arene. Org. Chem. Front. 2, 1013–1017 (2015).

Ni, M., Hu, X. Y., Jiang, J. & Wang, L. The self-complexation of mono-urea-functionalized pillar[5]arenes with abnormal urea behaviors. Chem. Commun. 50, 1317–1319 (2014).

Guan, Y. et al. Dynamic self-inclusion behavior of pillar[5]arene-based pseudo[1]rotaxanes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 12, 1079–1089 (2014).

Xia, B. & Xue, M. Design and efficient synthesis of a pillar[5]arene-based [1]rotaxane. Chem. Commun. 50, 1021–1023 (2014).

Sun, C. L. et al. Monofunctionalized pillar[5]arene-based stable [1]pseudorotaxane. Chinese Chem. Lett. 26, 843–846 (2015).

Sun, Y., Yao, Y., Yan, C. G., Han, Y. & Shen, M. Selective decoration of metal nanoparticles inside or outside of organic microstructures via self-assembly of resorcinarene. ACS Nano 4, 2129–2141 (2010).

Sun, Y., Yan, C. G., Yao, Y., Han, Y. & Shen, M. Self-assembly and metallization of resorcinarene microtubes in water. Adv. Funct. Mater. 18, 3981–3990 (2008).

Xiong, S. et al. Novel pseudo[2]rotaxanes constructed by the self-assembly of dibenzyl tetramethylene bis-carbamate derivatives and per-ethylated pillar[5]arene. Chem. Commun. 51, 6504–6507 (2015).

Duan, Q. et al. pH-responsive supramolecular vesicles based on water-soluble pillar[6]arene and ferrocene derivative for drug delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 10542–10549 (2013).

Ogoshi, T., Yamafuji, D., Aoki, T. & Yamagishi, T. A. Photoreversible transformation between seconds and hours time-scales: threading of pillar[5]arene onto the azobenzene-end of a viologen derivative. J. Org. Chem. 76, 9497–9503 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the financial support by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21172190, 21301119, 21302092) and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.-G.Y. and C.L. led this research. Y.H., G.-F.H., J.X., C.-G.Y., C.L. and L.W. conceived the project and designed the experiments. Y.H. and G.-F.H. performed all the synthetic work and conducted NMR, IR, HRMS, and computational work. J.S. and Y.Z. solved the single crystal X-ray structures. C.-G.Y. and C.L. wrote the paper, and Y.H., G.-F.H., X.W. and L.W. helped in paper preparation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Han, Y., Huo, GF., Sun, J. et al. Formation of a series of stable pillar[5]arene-based pseudo[1]-rotaxanes and their [1]rotaxanes in the crystal state. Sci Rep 6, 28748 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28748

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28748

This article is cited by

-

Construction of unique pseudo[1]rotaxanes and [1]rotaxanes based on mono-functionalized pillar[5]arene Schiff bases

Journal of Inclusion Phenomena and Macrocyclic Chemistry (2022)

-

Convenient construction of unique bis-[1]rotaxanes based on azobenzene-bridged dipillar[5]arenes

Journal of Inclusion Phenomena and Macrocyclic Chemistry (2022)

-

Self-assembly of bis-[1]rotaxanes based on diverse thiourea-bridged mono-functionalized dipillar[5]arenes

Journal of Inclusion Phenomena and Macrocyclic Chemistry (2022)

-

Dynamic Pseudorotaxane Crystals Containing Metallocene Complexes

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Single crystal structures and complexing properties of some copillar[5]arene mono-Schiff bases

Journal of Inclusion Phenomena and Macrocyclic Chemistry (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.