Abstract

Although oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs) have been associated with immunomodulation in preclinical studies, little is still known about the association between the use of OADs and the risk of sepsis. Using a cohort of patients, extracted from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database, with type 2 diabetes who were newly diagnosed between 2010 and 2012 and treated with OADs, we conducted a nested case-control study involving 43,015 cases (patients who were first hospitalized for sepsis) and 43,015 matched controls. Compared with non-use, metformin use was associated with a decreased risk of developing sepsis (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 0.80, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.77–0.83, P < 0.001), but meglitinide (adjusted OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.25–1.40, P < 0.001) use was associated with the increased risk of developing sepsis. The risk for development of sepsis was also lower among current (adjusted OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.78–0.96) and recent (adjusted OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.73–0.94) thiazolidinedione users. Current or recent sulfonylurea use and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor use were not significantly associated with the development of sepsis. Our results highlight the need to consider the potential pleiotropic effect of OADs against sepsis in addition to the lowering of blood glucose.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Between 1980 and 2008, the number of people with type 2 diabetes (T2D) worldwide increased from approximately 150 million to 350 million1. According to the World Health Organization, the global economic burden of T2D is tremendous, consuming 2.5–15% of countries’ primary healthcare budgets2. Till now, the use of oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs) remains the preferred pharmacological therapy due to many patients’ fear of insulin administration and its adverse effects, such as hypoglycemia and weight gain3,4.

Several classes of OAD are available on the market, including biguanide (metformin), sulfonylureas, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, meglitinides, thiazolidinediones (TZDs), dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors and newer sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. In addition to mediating glucose reduction, OADs have been associated with immunomodulation in preclinical studies5,6,7. In fact, patients with T2D are susceptible to infection and sepsis which may also impact on T2D lethality and medical costs in health systems; however, the possible pleiotropic effect of OADs on sepsis outcomes has not yet been well validated in large-scale clinical studies.

Previous studies8,9,10 exploring the association between OADs and sepsis have produced conflicting results, which may be attributed to methodological issues such as small samples, limited follow-up periods, unconfirmed diagnosis of infection events, unknown OAD exposure periods relative to sepsis onset, or the confounding effects of differences in diabetes severity between groups. To investigate whether susceptibility to sepsis differed among patients with T2D taking different classes of OAD, we used the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) to conduct a nationwide nested case-control study that controlled for the effects of predisposing the host factors to sepsis.

Methods

Data sources

Medical care in Taiwan has been provided under Taiwan’s National Health Insurance (NHI) since 1995. This system covers more than 99% of Taiwan’s inhabitants for most medical expenses related to inpatient, outpatient and emergency care, Chinese medicine and dental services. For administrative and reimbursement purposes, the Bureau of the NHI audited patients’ diagnosis, procedure and medication data to ensure correct coding and appropriateness; these data were recorded and stored in the NHIRD, which has been described in detail in our previous studies11,12. To examine OAD use among patients with T2D, we extracted the Longitudinal Cohort of Diabetes Patients dataset from the NHIRD. This dataset includes all available medical registry data for 120,000 patients with incident T2D per year during the period 1999–2012. This study was exempted from full review by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei City Hospital because it used de-identified and secondary claims data released by the NHIRD for research purposes.

Study population

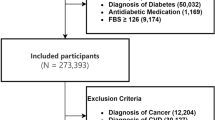

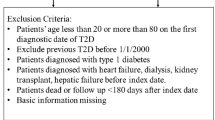

In this nationwide population-based study, we assembled a cohort of patients who received new diagnoses of diabetes between 2010 and 2012, as the marketing of DPP-4 inhibitors was approved in Taiwan in 2009. The definition of diabetes was based on the presence of one primary discharge diagnosis of diabetes (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 250.x), two ambulatory visits with a diagnosis of diabetes (ICD-9-CM code 250.x), or use of any antidiabetic drug. The accuracy of coded DM diagnoses in the NHIRD has been validated13. The date of cohort entry was the first day on which a patient fulfilled the diabetes diagnostic criteria. At cohort entry, all individuals were required to be at least 20 years old and have baseline medical history for at least 5 years (i.e., 2005–2009) available in the NHIRD; these data were used for verification purposes. We excluded those who had been hospitalized for sepsis before cohort entry. Each subject was followed until the outcome of hospitalization for sepsis, death, loss to follow up, or the end of the study period (31 December 2012).

Case definition and control selection

Because OAD exposure may be a time-dependent property associated with sepsis occurrence, we conducted a nested case-control analysis to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) for sepsis, comparing each OAD user with a nonuser of that drug. Cases were all patients hospitalized for sepsis (defined as a primary diagnosis of septicemia [ICD-9-CM code 038.x] plus the prescription of antibiotics) during the study period. We previously validated the accuracy of this definition of sepsis11. The index date was the day of the case’s hospital admission. For each case, we randomly selected a control matched according to age (±1 year), sex, month and year of cohort entry, level of urbanization, monthly income, Charlson Comorbidity Index score14, adapted Diabetes Complications Severity Index (aDCSI) score15 and duration of follow up.

Exposure assessment

All OAD prescriptions for each subject in the year before the index date were identified. The OADs of primary interest in the present study were metformin, sulfonylureas, TZDs, meglitinides and DPP-4 inhibitors. Given that preclinical studies16,17 have found that glibenclamide may have anti-inflammatory responses, but other sulfonylureas did not, we further stratified sulfonylureas into glibenclamide and non-glibenclamide sulfonylureas. For each OAD prescription, we collected the following information: dispensing date, drug type, quantity and duration of drug supply. The pattern of OAD use was categorized as current (on index date), recent (≤30 days before index date), or past (31–365 days before index date).

Statistical analysis

The baseline demographic characteristics of the cohort were analyzed using descriptive statistics. We conducted conditional logistic regression with adjustment for potential confounding factors, including OAD use, insulin use and all other predefined comorbidities associated with the risk of sepsis (Table 1). ORs were computed to compare OAD exposure of cases and controls. The Microsoft SQL Server 2012 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Washington, USA) was used for data linkage, processing and sampling. All analyses were performed using STATA statistical software (version 13.0; StataCorp., College Station, Texas, USA). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

A total of 43,015 cases and 43,015 matched controls were identified, with Table 1 showing their baseline characteristics. Hypertension, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease and drug abuse were more prevalent among cases than among controls.

Table 2 presents the crude and adjusted ORs for the development of sepsis requiring hospitalization (cases) in association with OAD use compared with controls, after adjusting for all potential confounders in Table 1. Metformin use was associated with decreased odds of developing sepsis (adjusted OR 0.80, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.77–0.83, P < 0.001), whereas sulfonylurea (adjusted OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.02–1.10, P = 0.001) and meglitinide (adjusted OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.25–1.40, P < 0.001) use were associated with increased odds of developing sepsis (Table 2). In addition, the timing of OAD use may be related with the onset of sepsis. Adjusted ORs for sepsis were 0.77 (95% CI 0.73–0.80) for current metformin use, 0.74 (95% CI 0.70–0.79) for recent metformin use and 0.90 (95% CI 0.86–0.95) for past metformin use. Neither current sulfonylurea use (adjusted OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.98–1.08) nor recent (adjusted OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.91–1.03) sulfonylurea use significantly increased the risk of sepsis. The results remained similar when sulfonylureas were classified as either glibenclamide or non-glibenclamide (Supplementary Table 1). Current (adjusted OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.78–0.96) and recent (adjusted OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.73–0.94) TZD use significantly decreased the risk of sepsis.

The comparisons of metformin-based combined therapy versus metformin alone on the risk of sepsis are summarized in Table 3. A decreased risk of sepsis was consistently observed in patients taking metformin alone (adjusted OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.62–0.68) and metformin-based combination therapy with sulfonylureas (adjusted OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.69–0.75), TZDs (adjusted OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.41–0.64), DPP-4 inhibitors (adjusted OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.55–0.78), or meglitinides (adjusted OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.71–0.96).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first population-based, nested case-control study to examine the relationship between OAD use and the risk of hospitalization for sepsis.

We found that metformin use was associated with about 20% reduced risk of sepsis compared with nonuse. In contrast, meglitinides and sulfonylureas was associated with increased risk of future sepsis events, but this association was not evident among recent and current sulfonylurea users. The effects of DPP-4 inhibitors and TZDs on sepsis were neutral, but a reduced risk of sepsis occurrence was observed only in recent/current TZD users. Nevertheless, metformin-based OADs conferred a persistent benefit on the rate of hospitalization for sepsis.

In-vitro studies have found that metformin treatment had an inhibitory effect on mediators of sepsis, such as by limiting respiratory Staphylococcus aureus growth8 and tuberculosis18 and mucormycosis19 infection and attenuating hepatitis B virus replication20. Similar to our findings, a Swedish population-based cohort study10 with a mean follow-up period of 3.9 years demonstrated that metformin treatment was associated with a reduced risk of composite outcomes of acidosis/serious infection (adjusted hazard ratio 0.85, 95% CI 0.74–0.97) in patients with T2D, independent of glycemic control, compared with those receiving other OADs (about 80% of which were sulfonylureas). Although relevant guidelines for diabetes treatment have suggested withdrawal from metformin for patients with sepsis due to concern about metformin-associated lactic acidosis21, this approach has been controversial because no proven evidence supports the increased risk of this condition among metformin users compared with users of other OADs22,23,24. In a single-center retrospective cohort study of 1,947 patients with septic emergent department events, a significant improvement in short-term survival of sepsis was noted for patients who had received metformin compared with those who had not (OR, 2.49; P < 0.01)25. Our nationwide study provided more evidence to support the association of metformin prescription with decreased risk of sepsis through the examination of patterns of past, recent, or current use. Furthermore, meglitinide prescriptions had the opposite effect on sepsis development, which appeared to be weaker for sulfonylurea users. Although investigation of the mechanism responsible for these relationships was beyond the scope of the present study, their propensities for insulin secretagogues by inhibiting the adenosine triphosphate–sensitive potassium channel in pancreatic β cells may also have off–target effects, which have been found to be related to impaired immune response against invading pathogens in preclinical studies26,27.

Recent/current, but not past, TZD prescription was associated with a modest reduction in sepsis risk, suggesting that this effect is immediate. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs)28,29 investigating the clinical effectiveness of add-on TZD therapy in patients with T2D showed no significant difference in additional infection risk between the TZD group and active controls; this is consistent with the findings of the present study. Only a modest potential benefit from TZD in sepsis onset may be offset in intention-to-treat analyses conducted in RCTs, as some patients were lost to follow up or withdrew from the medication during the follow-up period. In contrast, a meta-analysis8 of 13 trials showed that TZD use was associated with greater risks of upper and lower respiratory-tract infections, but low (<2% overall) event rates of sepsis and differences in follow-up periods (1–5 years) among trials may have affected the accuracy of estimates of incident sepsis events.

No association between DPP-4 inhibitors and sepsis risk was observed in the present study. DPP-4 inhibition may have pleiotropic effects, modulating the immune response by binding DPP-4 receptors of immune cells30 or culprit pathogens, such as coronavirus and hepatitis C virus31,32. The balance between immune inhibition and anti-inflammation may be responsible for infection risk in DPP-4 inhibitor users. In the context of weighing the pros and cons of DPP-4 inhibitor use given the effects of these drugs on immune function, our results show that they have an insignificant influence of sepsis risk. A nested control study based on the World Health Organization Vigibase9 showed that DPP-4 inhibitor use was associated with a greater risk of infection compared with metformin use. However, this result should be interpreted with caution, as the imprecise definition of infection based on spontaneous reporting introduces reporting bias.

The strengths of the present study include the analysis of large case and control groups respectively representing the nationwide diabetes populations that had previously received OADs either with or without sepsis from 2010–2012, which thus minimized referral bias. Additionally, we investigated whether the impact of OADs on the occurrence of sepsis was immediate or persistent over time by considering OAD exposure intervals. Still, this study has a few potential limitations. First, it was retrospective and observational in nature and so causality could not be established. Second, the diagnosis of diabetes and sepsis based on ICD-9 CM codes may have introduced misclassification bias; however, this bias could be non-differential and robust agreement between diagnoses established by coding and clinical criteria has been demonstrated elsewhere11,13. Third, the claims database did not include individual baseline data on glycemic control, such as HbA1c levels. Nonetheless, if the impact of OADs on sepsis outcome were mainly the result of the glucose-lowering effect, the tendency of ORs for different OADs should tend toward coherence. Therefore, it is unlikely that this unmeasured confounder biased the results and its effects were minimized by adjusting for the aDCSI score. Lastly, data on potential confounders such as obesity, smoking habit and alcohol consumption were also unavailable in the database.

In conclusion, metformin and recent or current TZD use were inversely associated with sepsis occurrence, whereas meglitinide use was positively associated with sepsis occurrence. As patients with T2D are predisposed to infection, the direct impacts of OADs on future sepsis events should be considered.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Shih, C.-J. et al. Association between Use of Oral Anti-Diabetic Drugs and the Risk of Sepsis: A Nested Case-Control Study. Sci. Rep. 5, 15260; doi: 10.1038/srep15260 (2015).

References

Danaei, G. et al. National, regional and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 370 country-years and 2.7 million participants. Lancet 378, 31–40, 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60679-X (2011).

Mann, J. F., Gerstein, H. C., Pogue, J., Bosch, J. & Yusuf, S. Renal insufficiency as a predictor of cardiovascular outcomes and the impact of ramipril: the HOPE randomized trial. Annals of internal medicine 134, 629–636 (2001).

Iacobucci, G. Diabetes prescribing in England consumes nearly 10% of primary care budget. Bmj 349, g5143, 10.1136/bmj.g5143 (2014).

Hampp, C., Borders-Hemphill, V., Moeny, D. G. & Wysowski, D. K. Use of antidiabetic drugs in the US, 2003–2012. Diabetes care 37, 1367–1374, 10.2337/dc13-2289 (2014).

Garnett, J. P. et al. Metformin reduces airway glucose permeability and hyperglycaemia-induced Staphylococcus aureus load independently of effects on blood glucose. Thorax 68, 835–845, 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-203178 (2013).

Karagiannis, E. et al. The IRIS V study: pioglitazone improves systemic chronic inflammation in patients with type 2 diabetes under daily routine conditions. Diabetes technology & therapeutics 10, 206–212, 10.1089/dia.2008.0244 (2008).

Shah, Z. et al. Long-term dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 inhibition reduces atherosclerosis and inflammation via effects on monocyte recruitment and chemotaxis. Circulation 124, 2338–2349, 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.041418 (2011).

Singh, S., Loke, Y. K. & Furberg, C. D. Long-term use of thiazolidinediones and the associated risk of pneumonia or lower respiratory tract infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 66, 383–388, 10.1136/thx.2010.152777 (2011).

Willemen, M. J. et al. Use of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and the reporting of infections: a disproportionality analysis in the World Health Organization VigiBase. Diabetes care 34, 369–374, 10.2337/dc10-1771 (2011).

Ekstrom, N. et al. Effectiveness and safety of metformin in 51 675 patients with type 2 diabetes and different levels of renal function: a cohort study from the Swedish National Diabetes Register. BMJ open 2, 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001076 (2012).

Chao, P. W. et al. Association of postdischarge rehabilitation with mortality in intensive care unit survivors of sepsis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 190, 1003–1011, 10.1164/rccm.201406-1170OC (2014).

Shih, C. J. et al. Long-term clinical outcome of major adverse cardiac events in survivors of infective endocarditis: a nationwide population-based study. Circulation 130, 1684–1691, 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012717 (2014).

Lin, C. C., Lai, M. S., Syu, C. Y., Chang, S. C. & Tseng, F. Y. Accuracy of diabetes diagnosis in health insurance claims data in Taiwan. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association = Taiwan yi zhi 104, 157–163 (2005).

Charlson, M. E., Pompei, P., Ales, K. L. & MacKenzie, C. R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of chronic diseases 40, 373–383 (1987).

Chang, H. Y., Weiner, J. P., Richards, T. M., Bleich, S. N. & Segal, J. B. Validating the adapted Diabetes Complications Severity Index in claims data. The American journal of managed care 18, 721–726 (2012).

Lamkanfi, M. et al. Glyburide inhibits the Cryopyrin/Nalp3 inflammasome. J Cell Biol 187, 61–70, 10.1083/jcb.200903124 (2009).

Koh, G. C. et al. Glyburide is anti-inflammatory and associated with reduced mortality in melioidosis. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 52, 717–725, 10.1093/cid/ciq192 (2011).

Singhal, A. et al. Metformin as adjunct antituberculosis therapy. Science translational medicine 6, 263ra159, 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009885 (2014).

Shirazi, F. et al. Diet modification and metformin have a beneficial effect in a fly model of obesity and mucormycosis. PloS one 9, e108635, 10.1371/journal.pone.0108635 (2014).

Xun, Y. H. et al. Metformin inhibits hepatitis B virus protein production and replication in human hepatoma cells. Journal of viral hepatitis 21, 597–603, 10.1111/jvh.12187 (2014).

Jones, G. C., Macklin, J. P. & Alexander, W. D. Contraindications to the use of metformin. Bmj 326, 4–5 (2003).

Salpeter, S. R., Greyber, E., Pasternak, G. A. & Salpeter, E. E. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, CD002967, 10.1002/14651858.CD002967.pub4 (2010).

Bodmer, M., Meier, C., Krahenbuhl, S., Jick, S. S. & Meier, C. R. Metformin, sulfonylureas, or other antidiabetes drugs and the risk of lactic acidosis or hypoglycemia: a nested case-control analysis. Diabetes care 31, 2086–2091, 10.2337/dc08-1171 (2008).

Inzucchi, S. E., Lipska, K. J., Mayo, H., Bailey, C. J. & McGuire, D. K. Metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes and kidney disease: a systematic review. Jama 312, 2668–2675, 10.1001/jama.2014.15298 (2014).

Green, J. P. et al. Impact of metformin use on the prognostic value of lactate in sepsis. The American journal of emergency medicine 30, 1667–1673, 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.01.014 (2012).

Kewcharoenwong, C. et al. Glibenclamide reduces pro-inflammatory cytokine production by neutrophils of diabetes patients in response to bacterial infection. Scientific Reports 3, 3363, 10.1038/srep03363 (2013).

Eleftherianos, I. et al. ATP-sensitive potassium channel (K(ATP))-dependent regulation of cardiotropic viral infections. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108, 12024–12029, 10.1073/pnas.1108926108 (2011).

Dezsi, C. A. Differences in the clinical effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and Angiotensin receptor blockers: a critical review of the evidence. American journal of cardiovascular drugs : drugs, devices and other interventions 14, 167–173, 10.1007/s40256-013-0058-8 (2014).

Dormandy, J. A. et al. Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 366, 1279–1289, 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)67528-9 (2005).

van Poppel, P. C., Gresnigt, M. S., Smits, P., Netea, M. G. & Tack, C. J. The dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor vildagliptin does not affect ex vivo cytokine response and lymphocyte function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes research and clinical practice 103, 395–401, 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.12.039 (2014).

Raj, V. S. et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature 495, 251–254, 10.1038/nature12005 (2013).

Yanai, H. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor sitagliptin significantly reduced hepatitis C virus replication in a diabetic patient with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatobiliary & pancreatic diseases international: HBPD INT 13, 556 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This study was based in part on data from the NHIRD provided by the Bureau of NHI, Department of Health and managed by National Health Research Institutes. The interpretations and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of Bureau of NHI, Department of Health and National Health Research Institutes. Sources of Funding: Financial support: This study was supported in part by grants from Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V104A-003 and V104E4-003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.T.C., S.M.O., C.J.S. and Y.L.W. conceptualised and designed the study and drafted the article; Y.T.C., S.M.O., C.J.S. and Y.L.W. analysed and interpreted the data; Y.T.C., S.M.O., C.J.S. and Y.L.W. critically revised the article for important intellectual content; Y.T.C., S.M.O. and P.W.C. provided final approval of the article; S.C.K. provided study materials and patients; P.W.C., C.Y.Y. and S.Y.L. offered statistical expertise and provided administrative, technical and logistical support.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Shih, CJ., Wu, YL., Chao, PW. et al. Association between Use of Oral Anti-Diabetic Drugs and the Risk of Sepsis: A Nested Case-Control Study. Sci Rep 5, 15260 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep15260

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep15260

This article is cited by

-

Metformin reverse minocycline to inhibit minocycline-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii by destroy the outer membrane and enhance membrane potential in vitro

BMC Microbiology (2022)

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus and sepsis: state of the art, certainties and missing evidence

Acta Diabetologica (2021)

-

Incidence and risk of sepsis following appendectomy: a nationwide population-based cohort study

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Metformin Use and Severe Dengue in Diabetic Adults

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Effectiveness and safety of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors in the management of type 2 diabetes in older adults: a systematic review and development of recommendations to reduce inappropriate prescribing

BMC Geriatrics (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.