Abstract

Objective: To report three cases of intradural spinal tuberculosis (TB) by calling attention to atypical forms of spinal TB.

Setting: A University Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey.

Methods: Histopathological, radiological, surgical and physical examination findings of three patients with spinal TB were retrospectively reviewed.

Results: Based on histopathological, surgical and radiological findings, diagnosis of intramedullary abscess had been made in the first case and early and late phases of arachnoiditis in the other two patients, respectively.The clinical outcome was evaluated as satisfactory for the patient with intramedullary abscess who had been treated with medical and surgical interventions. The remaining two patients with arachnoiditis, who had been treated by shunting or simple decompression, had a relatively less favorable clinical outcome.

Conclusion: Spinal TB, in its atypical forms, is a rare clinical entity and low index of suspicion on the part of the surgeon may result in misdiagnosis such as neoplasm. In cases presenting with an intraspinal mass lesion, possibility of a tuberculous abscess and/or a granuloma should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is the most common cause of vertebral body infection not only in underdeveloped and developing countries but in developed countries as well because of an increasing number of immune-compromised patients. While the clinical manifestations and radiological features of classical spinal TB are well known and the diagnosis is readily made,1,2 some atypical forms have been reported,3,4,5 and 6 which may prevent early recognition of the disorder and accurate diagnosis. These atypical forms of spinal TB should be kept in mind in order to establish an early diagnosis and treatment, which otherwise may result in irreversible neurological sequela.

We retrospectively reviewed the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies and reports of surgical findings of three cases with intradural spinal TB. The first case had a intramedullary abscess, the second had arachnoiditis with syrinx and the third had arachnoiditis. All three diagnoses were confirmed by histopathological studies.

Case reports

Case 1

A 7-year-old male patient had been admitted with pain in the mid-dorsal region of 8 months duration. Other complaints were urinary incontinence, progressive weakness in both legs for a week and a severe suboccipital headache for 2 days. There was no history of trauma. Neurological examination revealed weakness (3/5) of both lower extremities; knee and ankle jerks were hyperactive bilaterally. Sensory examination revealed hypoesthesia below T10 level. Babinski sign was present bilaterally. Other important physical findings were stiff neck and weakness in right lateral rectus muscle. There was no spinal tenderness.

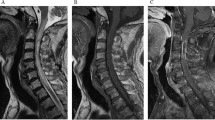

Laboratory examination revealed a WBC of 10.500/mm3, hemoglobin 10.4 g/dl and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 8 mm/h. Delayed hypersensitivity test for purified tuberculin derivatives was also positive. Chest X-ray revealed interstitial infiltration in the left lung lower lobe. Spinal X-ray of the dorsal spine was normal. Contrast-enhanced MRI study of thoracic spine revealed a well-circumscribed, cystic intramedullary mass at T7 level with ring enhancement (Figure 1). The spinal cord was locally enlarged and edematous. These findings suggested an infection rather than tumor. Computerized tomography image of the cranium disclosed an obscure inferior vermian lesion, which later on was evaluated as a probable tuberculoma.

The patient had undergone left T7–T8 hemilaminectomy. There was no pathology in the epidural space, dura was found to be tense and the cord was swollen. The arachnoidal membrane was thick and cloudy. There was a thin rounded projection emerging from the spinal cord from where a thick creamy pus was aspirated and sent for culture. Gram stains for bacteria were negative, but acid–alcohol-fast bacilli were found in the specimen. A diagnosis of tuberculous abscess was made.

Chest X-ray findings of the patient had revealed interstitial infiltrations in the left lung lower lobe providing a clue for the route of spread of the infection. The cultures of the biopsy specimen were all negative for anaerobic organisms, fungi and tuberculosis. Histopathological investigation revealed chronic inflammation and caseation necrosis. Great sheets of delicate vessels, which were lined by a flattened endothelium and separated by scant connective tissue stroma were also observed (Figure 2). After surgical drainage of the abscess and treatment with isoniazid, rifampicine and streptomycine combination plus 40 mg/dl methylprednisolone, the neurological symptoms had improved and the patient was discharged with moderate neurological deficit. At 7 weeks after discharge, he was walking independently and the sensorial impairment, right lateral rectus palsy and meningismus had completely resolved. MRI study at this time revealed a tuberculoma in the vermis cerebelli and obviously diminished abscess cavity in the spinal cord. At 11th month follow-up, he was still under treatment with isoniazid plus rifampicine and had developed mild spasticity in both lower extremities. Chest X-ray and spinal MRI studies at this time revealed no evidence of active TB. After 5 years, the patient had become totally asymptomatic.

Case 2

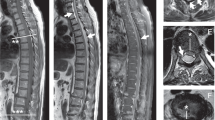

A 30-year-old female patient had been admitted to our department with the complaint of progressive weakness of both legs. She had been treated for tuberculous meningitis 9 years ago (April 1992). She had antituberculous therapy at that time consisting of four drugs (isoniazid, rifampicine, pyrazinamide and ethambutol) for 18 months and also had been taken into a rehabilitation program. Within 2 years, she had a substantial recovery except for minimal weakness in her legs, which necessiated an MRI study of the spinal cord. MRI examination at that time revealed a thoracic syrinx extending from T3 to T9 levels and arachnoiditis with atrophy of the cord between T1 and T2 levels (Figure 3). During the following 2 years, she had been treated conservatively and her complaint continued. At 4 years after the diagnosis of TB meningitis, she developed a progressive weakness for the second time in both lower extremities accompanied by bladder and bowel incontinence and numbness below the umbilicus. On admission (October 1996) she was fully alert, conscious, well oriented and the neurological examination of the cranial nerves and upper extremities was normal. Examination of the lower extremities revealed spastic paraparesis (2/5) with diffuse muscular wasting; deep tendon reflexes were brisk, Babinski sign was positive and abdominal reflexes were absent. Other important findings were decreased sensation to pinprick below T6 dermatome, loss of vibration and position sense and urinary incontinence. MRI studies of the spinal cord at this time revealed extensive arachnoiditis with multiloculated syrinxes extended from T3 to T10. Compared to the previous magnetic resonance images, syringomyelic cavitations were found to be increased in size. Dilatations of the syrinxes were considered to be responsible for the recent neurological deterioration and a syringo-subarachnoidostomy was planned. After T5–T6 hemilaminectomy and opening of the dura, arachnoid was reached, which was thickened and cloudy in appearance.

A ‘T’ tube (Medtronic PS Medical, CA, USA) was inserted into the syrinx cavity via myelotomy. Clear fluid under moderately elevated pressure drained freely and the caudal end of the catheter was placed under the arachnoidal membrane.

Histopathologically, the lesion was composed of lobulated but uncapsulated aggregations of closely packed, thin-walled capillaries usually filled by blood and lined by a flattened endothelium (Figure 4).

On the first postoperative day, the patient showed a dramatic improvement and began to walk with minimal assistance within a week. Unfortunately, this improvement progressively declined after the first postoperative month. At 2 years after the surgical intervention control, MRI study revealed that the syringostomy was patent, and the cavity was diminished: but there was no improvement in the neurological picture. At 2.5 years after the surgical procedure, the patient began to complain of burning type dysesthesias and showed deterioration in neurological function. Thoracic spinal MRI study at that time disclosed enlargement of the syringomyelic cavities. A second operation was performed in which a syringo-peritoneal shunt was inserted using a ‘T’ tube via right T10–11 hemilaminectomy. On day 1 after the operation, the dysesthetic pain was relieved, motor power of the lower extremities improved and the spasticity began to decrease. Control MRI after 10 weeks revealed significantly diminished syringomyelic cavities. At 4 months after this second operation, the neurological picture showed improvement with minimal gait disturbance (Table 1).

Case 3

A 21-year-old male patient had been admitted with complaints of progressive weakness in both legs and loss of bowel and bladder control for 1 week. He had been treated for TB meningitis 2 years ago (January 1999). He had been treated with four antituberculous drugs regularly for 4 months, but he had not used his medication regularly after discharge from the hospital.

Neurological examination on admission revealed motor weakness in both lower extremities (3/5). There was no spinal tenderness. Knee and ankle jerks were diminished bilaterally; upper, middle and lower abdominal reflexes were absent. Sensory examination revealed decreased sensation to pinprick below T4 dermatome accompanied by loss of position and vibration sense. The Babinski sign was positive bilaterally. He had urinary retention. These findings suggested a picture of spinal cord compression. Laboratory examination revealed a WBC of 9500/mm3, hemoglobin 14.1 g/dl and ESR of 10 mm/h. The plain radiograms of the dorsal spine and the chest were normal. Contrast enhanced MRI study of the thoracic spine disclosed a homogeneous pathologically enhancing intradural lesion extending from T3 to L2 and covering the cord posterolaterally (Figure 5).

A left T8–10 hemilaminectomy was performed. There was no pathology in the epidural space; dura was found to be tense. Arachnoidal membrane was thickened and cloudy in appearance. A soft, partially hemorrhagic pink-colored mass was demonstrated, which was densely adhered to the spinal cord and the nerve roots. Histopathological examination of the biopsy specimen taken from this mass revealed chronic inflammation and granuloma formation. The dura was left open and paraspinal muscles were closed in watertight fashion. After the decompression of the cord, methylprednisolone and anti-TB drugs were administered.

Histopathological examination disclosed few noncaseating epitheloid cell granulomas. The peripheral zones of the granulomas contained loosely arranged cellular elements including fibroblasts, epitheloid cells and chronic inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes, plasma cells and eosinophils (Figure 6). Ziehl Neelsen staining was negative for the bacilli.

On day 10 after surgery, the patient began to walk with assistance, his sensory deficit partly resolved and he regained bladder control. At 14 months after the operation, he was able to walk independently. Neurological examination at this time revealed slight spastic paraparesis (4/5) with minimal gait disturbance. His sensory deficit had resolved completely. MRI study of the dorsal spinal cord at this time disclosed extensive arachnoiditis with multiloculated syrinxes extending from T3 to T10.

Clinical, radiological and histopathological features and functional outcomes of all cases were presented in Table 1.

Discussion

Tuberculosis, caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a chronic infectious disease characterized by the formation of granuloma and rarely of abscess in the infected tissue.7 The central nervous system involvement is very rare affecting 0.5–2% of the cases. The incidence of TB has gradually increased in recent years owing to the aging of the general population and also because of the increased number of people with drug abuse, AIDS and other conditions or medications leading to immunosuppression.1 Spinal TB is the most common form of osteoarticular TB.8

The present paper reports three cases of atypical spinal TB with pure intradural involvement, which have been recently documented in the literature:3,4,5 and 6 arachnoiditis with intramedullary abscess, arachnoiditis with syrinx, and arachnoiditis with subdural empyema, without epidural involvement. Since such types of involvement are uncommon or less reported, these cases should be considered as nonclassical or atypical spinal TB. Spinal TB is known to be associated mainly with pulmonary disease and may originate in three ways: (1) by hematogenous spread from an origin outside the CNS, (2) via secondary extension caudally from cranial tuberculous meningoencephalitis and (3) by secondary intraspinal extension from osteoarticular or discal TB. Hematogenous spread from an origin outside the CNS was reported to be the most common route of infection resulting in radiculomyelopathy.9 In the early stages of the spinal TB, variable degrees of congestion and inflammatory exudate may be demonstrated in the meninges of the cord.10 The spinal cord and the nerve roots may become edematous and surrounded by gelatinous exudate similar to our intraoperative findings of cases 1 and 2. Although the thoracic spine was reported to be the most common site of involvement, tuberculoma or TB abscess may develop anywhere within the thecal sac.9,11,12 and 13 It is usually closely adherent to the inner aspect of the dura and to the cord into which it penetrates like a crater, so in occasional cases it becomes very difficult to define whether the intradural tuberculoma is extramedullary or intramedullary.13,14

Intramedullary spinal cord abscess is a rare clinical entity and only 83 cases15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30 and 31 have been reported in the literature since the original case documented by Hart in 1830.25 Abscess formation becomes manifest by the accumulation of the necrotic tissue, debris and caseous material as the disease progresses. Abscess frequently bursts through or passes around the anterior or posterior longitudinal ligament and may spread to distant anatomical regions from the original site of the infection.32 In the first two cases presented in our paper, abscess had been found to be localized to the site of infection. This finding, which seems to conflict with the previous reports, may partly be explained by the increased sensitivity of MRI studies in recent years and the early detection of these cases because of the established neurological picture secondary to the cord or nerve root compression.

Arachnoiditis is characterized by inflammation of the leptomeninges which may result from infections, intrathecal administration of chemical agents, subarachnoid hemorrhage, trauma, surgical scar and some other intervertebral disc pathologies.33 Tuberculosis is the most common cause of this disorder and radiculomyelitis is almost always present in the course of tuberculous arachnoiditis.11 In all the cases presented in our paper, the arachnoidal membranes were thickened and cloudy with apparent adhesions. Syringomyelia, which is characterized by abnormal cavitation of the spinal cord is an uncommon and a late complication of spinal TB.34,35,36,37 and 38 This pathology had been demonstrated in our case 2 as a late complication of spinal TB.

Syringomyelia was first described by Vulpian (1861) and Charcot and Joffery (1869); but ‘TB caused’ syringomyelia was first described by Marinesco in 1916. The mechanisms of syrinx formation secondary to inflammatory arachnoiditis have also been described in the literature.35,39 Caplan et al34 and MacDonald et al39 reported that inflammatory arachnoiditis may produce an extensive obliterative endarteritis, which results in an ischemic injury in the cord parenchyma. In fact, MacDonald et al39 suggested that ischemic myelomalacia antedates the development of syringomyelia because of arachnoiditis. Whatever the mechanism, in terms of clinical presentation, it is very important to keep in mind that development of syringomyelic cavities may be responsible for the late neurological deterioration in these patients.

Spinal TB may present with a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations and the medical history is seldomly helpful in the differential diagnosis. Fever and systemic symptoms may not become evident until the late stage. Almost half of the patients with extrapulmonary TB have normal chest X-ray findings.40 In a majority of the cases ESR is elevated and skin tests are usually positive.41 ESR had been found to be within the normal range in all our patients while the skin tests were positive in two cases.

Multiple imaging modalities such as conventional radiography, scintigraphy, computed tomography and myelography have all been reported to be helpful in the diagnosis of spinal TB, but MRI is relatively more sensitive and is believed to be the modality of choice in the appropriate clinical setting.8,38 Gadolinium-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid-enhanced MRI study helps to demonstrate the classical ring sign of an abscess,23,31 and can also differentiate myelomalacia from a syrinx. It should be the radiological study of choice in both the diagnosis and the follow-up of this disorder. The treatment of intramedullary abscess should include a combination of surgical and pharmacological therapies. Surgery is indicated for the evacuation of the pus and use of appropriate antibiotics and corticosteroids should be considered in the treatment.16,27,31 Treatment of syringomyelia secondary to spinal TB consists of a shunting procedure, which has a limited success rate as occurred in our case 2.

References

Esses SI . Infections of the spine. In: Esses SI (ed). Textbook of Spinal Disorders. JB Lippincott, Philadelphia, 1995, pp 229–241.

Hodgson AR . Tuberculosis of the spine. In: Rothman RH, Simeone FA (eds). The Spine. WB Saunders: Philadelphia, 1975, pp 573–595.

Naim-Ur-Rahman . Atypical forms of spinal tuberculosis. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1980; 62B: 162–165.

Naim-Ur-Rahman, AI-Arabi KM, Khan FA . Atypical forms of spinal tuberculosis. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1987; 88: 26–33.

Weaver P, Lifeso RM . The radiological diagnosis of tuberculosis of the adult spine. Skeletal Radiol 1984; 12: 178–186.

Naim-Ur-Rahman, Jamjoon AB, Jamjoon ZAB, AI-Tahan AM . Neural arch tuberculosis: radiological features and their correlation with surgical findings. Spinal Cord 1997; 11: 32–38.

Bannister CM . A tuberculous abscess of the brain. J Neurosurg 1970; 33: 203–206.

Shanley DJ . Tuberculosis of the spine: imaging features. Am J Neurol Rheumatol 1995; 164: 659–664.

Wadia NH, Dastur DK . Spinal meningitides with radiculomyelopathy, Part 1: clinical and radiological features. J Neurol Sci 1969; 8: 239–260.

Chang KH et al. Tuberculous arachnoiditis of the spine: findings on myelograpy, CT, and MR imaging. Am J Neuroradiol 1989; 10: 1255–1262.

Kumar A et al. MR features of tuberculosis arachnoiditis. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1993; 17: 127–130.

Grupta RK et al. MRI in intraspinal tuberculosis. Neuroradiology 1994; 36: 39–43.

Arseni G, Samitca DC . Intraspinal tuberculous granuloma. Brain 1960; 83: 285–292.

Kozlowski K . Late spinal blocks after tubercular meningitis. Am J Rheumatol 1963; 90: 1220–1226.

Koppel BS, Daras M, Duffy KR . Intramedullary spinal cord abscess. Neurosurgery 1990; 26: 145–146.

Hanci M, Sarioğlu AÇ, Uzan M, Işlak C, Kaynar MY, Öz B . Intramedullary tuberculous abscess. Spine 1996; 21: 766–769.

Ameli NO . A case of intramedullary abscess: recovery after operation. BMJ 1948; 2: 138.

Byrne RW, Von Roenn KA, Whisler WW . Intramedullary abscess: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 1994; 35: 321–326.

Carus MME, Anciones B, Lara M, Isla A . Intramedullary spinal cord abscess. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992; 55: 225–226.

Cheng KM, Ma MW, Chan CM, Leung CL . Tuberculous intramedullary spinal cord abscess. Acta Neurochir 1997; 139: 1189–1190.

D'Angelo CM, Whisler WW . Bacterial infections of spinal cord and its coverings. In: Vinken, PJ, Bruyn GW (eds). Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 3rd edn. North Holland Publishing Co: Amsterdam 1978, pp 191–194.

DiTullio Jr MV . Intramedullary spinal bascess: a case report with a review of 53 patients previously described cases. Surg Neurol 1977; 7: 351–354.

Erlich JH et al. Acute intramedullary spinal cord abscess: case report. Surg Neurol 1992; 38: 287–290.

Foley J . Intramedullary abscess of the spinal cord. Lancet 1949; 2: 193–194.

Hart J . A case of encysted abscess in the centre of spinal cord. Dublin Hosp Rep 1830; 5: 522–524.

Manfredi M, Bozzao L, Frasconi F . Chronic intramedullary abscess of the spinal cord. J Neurosurg 1970; 33: 352–355.

Menezes AH, Graf CJ, Perret GE . Spinal cord abscess: a review. Surg Neurol 1977; 8: 461–467.

Ratleff JK, Connolly ES . Intramedullary tuberculoma of the spinal cord: case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg (Spine) 1999; 90: 125–128.

Tacconi L, Arulampalam T, Johnston FG, Thomas DGT . Intramedullary spinal cord abscess: case report. Neurosurgery 1995; 37: 817–819.

Thome C, Krauss JK, Zevgaridis D, Schmiedek P . Pyogenic abscess of the filum terminale. J Neurosurg (Spine 1) 2001; 95: 100–104.

Tewari MK et al. Intramedullary spinal cord abscess: a case report. Child Nerv Syst 1992; 8: 290–291.

Tandon PN . Tuberculous meningitis (cranial and spinal). In: Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW (eds). Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Infections of the Nervous System, Part I. North-Holland: Amsterdam 1978, pp 195–262.

Whisler WW . Chronic spinal arachnoiditis. In: Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW (eds). Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Infections of the Nervous System, Part 1. Elsevier–North-Holland Biomedical Amsterdam 1978, pp 33, 263–274.

Caplan LR, Norohna AB, Amico LL . Syringomyelia and arachnoiditis. J Neurosurg Psychiatry 1990; 53:106–113.

Fehling MG, Bernstein M . Syringomyelia as an complication of tuberculous meningitis. Can J Neurol Sci 1992; 19: 84–87.

Kaynar MY, Koçer N, Gençosmanoğlu BE, Hanci M . Syringomyelia – as a late complication of tuberculous meningitis. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2000; 142: 935–939.

Savoirado M . Syringomyelia associated with postmeningitic spinal arachnoiditis. Neurology 1976; 26: 551–554.

Sharif HS et al. Granulomatous spinal infections of MR imaging. Radiology 1990; 177: 101–107.

MacDonald RL, Findlay JM, Tator CH . Microcystic spinal cord degeneration causing post-traumatic myelopathy. J Neurosurg 1988; 68: 446–471.

Simon HB . Infections due to mycobacteria. In: Rubinstein NE, Federman D (eds). Scientific American Medicine Update 6/94. Scientific American Medicine: New York 1994, p 1.

Fam AG, Rubenstein I . Another look at spinal tuberculosis. J Rheumatol 1993; 20: 1731–1740.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tanriverdi, T., Kizilkiliç, O., Hanci, M. et al. Atypical intradural spinal tuberculosis: report of three cases. Spinal Cord 41, 403–409 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101463

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101463

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Spontaneous intramedullary abscesses caused by Streptococcus anginosus: two case reports and review of the literature

BMC Infectious Diseases (2022)

-

Spinal cord involvement in tuberculous meningitis

Spinal Cord (2015)

-

Intramedullary spinal cord abscess as complication of lumbar puncture: a case-based update

Child's Nervous System (2013)

-

Incidence and profile of spinal tuberculosis in patients at the only public hospital admitting such patients in KwaZulu-Natal

Spinal Cord (2008)