Key Points

-

A postal questionnaire investigating factors influencing specialist referral in restorative dentistry.

-

Increasing patient expectations and the potential for medico-legal litigation are the main promoters of restorative referrals.

-

Promoters and barriers to referral differ for NHS and private general dental practitioners.

-

Overall demand is for a prompt, locally-based, cost effective specialist referral service.

Abstract

Objectives To determine the level of demand from general dental practitioners (GDPs) for specialist restorative dental services in the Yorkshire region. To investigate barriers and promoters to referral and GDPs' perceptions of restorative mono-specialists.

Methods A postal questionnaire was sent to 301 randomly selected GDPs (stratified for location) registered in the six Family Health Service Units in Yorkshire. Questionnaires were piloted prior to release; reminders were sent to non-respondents.

Results A response rate of 72% (n=217) was achieved, of these 195 questionnaires were useable (65% useable response rate). Results showed a large demand for restorative specialist services. Main promoters for National Health Service (NHS) referral were dentolegal issues (77% GDPs ranked this as a top three promoter) and for private referral increasing patient expectations (78%). The top barriers against referral were length of waiting lists for NHS patients (79% GDPs ranked this as a top three barrier) and high cost of treatment for private patients (88%). Excessive distance to specialist centre was the greatest barrier common to both NHS and private referrals. Fifty-eight per cent of GDPs would prefer to refer private patients to mono-specialists, compared with 5% who would prefer restorative specialists.

Conclusions There is a strong demand for specialist restorative services which may increase in the future. Results indicate a high regard for mono-specialists. Overall demand is for a prompt, locally based, low cost referral service.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 1998 the General Dental Council (GDC) set up registered specialist lists.1 The purpose of these lists was to formalise specialisation in dentistry and to improve and standardise the quality of dental care for patients.2,3 Restorative dentistry has existed as a speciality in the UK since 1973 with training programmes leading to consultant appointments in the hospital service. It is only since April 1998 that restorative specialists have been formally recognised by the GDC. Three mono-specialist lists were introduced at that time, which are sub-divisions of restorative dentistry; these are endodontics, periodontics and prosthodontics. Individuals on mono-specialist lists may only have training in that specific branch of restorative care or may be restorative specialists whose training includes all three mono-disciplines. Prior to application to join the specialist lists in restorative dentistry or a restorative mono-speciality, an applicant must have completed a recognised training programme, standardised and maintained by the GDC4 (Fig. 1.1)

Training pathway for restorative and restorative mono-speciality specialists1

Currently there are 1,070 names on the restorative mono-speciality lists,5 although many individuals are included on more than one list (Fig. 2).

Numbers of individuals on each restorative and mono-speciality list5

Members of the specialist restorative services may work in a variety of areas including hospital, community, academic, NHS or private practice with many practitioners working in more than one environment. Practitioners who are purely mono-specialist cannot work as consultants in hospitals and as a result the majority form a practice-based service.

The success of a specialist relies greatly on their colleagues to provide a continual flow of referrals. To be used fully, a specialist needs general dental practitioners to have good referral awareness6 (that is, knowing which patients to refer, when to refer and where to refer to7). Currently attempts are being made to form an Index of Restorative Treatment Need, which may be used to aid referrers as to what treatment may benefit from specialist input.8 Such schemes are already used successfully in Orthodontics (IOTN).9 Local referral guidelines have been introduced in some areas, although there is little evidence yet on benefits they may offer GDPs.10 The NHS National Plan11,12 however, suggests that more guidelines should be formulated in future to provide criteria for appropriate referrals.

The demand for specialist restorative services has been shown to be influenced by other factors; the perceived supply of specialists, distance from the GDP's practice and the working environments of specialists.7 Patients will also influence a GDP's demand for these services as they may be unwilling or unable to pay for private specialist treatment, to travel long distances or wait long periods to see a specialist.

The aims of the study were:

-

To investigate the demand for specialist restorative services in the Yorkshire region

-

To investigate barriers and promoters to referral

-

To explore GDPs' perception of mono-specialists.

Materials and methods

A postal questionnaire was sent to a sample of GDPs in the Yorkshire region (n=301). Every fourth name on each family health service unit (FHSU) list was included, providing a random sample stratified for location. This method gave a representative sample size of each FHSU and mix of rural and urban practitioners, thus reflecting the population as a whole.

The questionnaire was of a mainly closed response format and was piloted twice on 20 GDPs each time before its full scale release. Minor adjustments were made to ensure the questionnaire was clear to understand and easy to complete. Questions covered general information such as gender, year of qualification and percentage of private and NHS work undertaken. The questionnaire went on to assess which specialist services GDPs were aware they had access to and how often they used these services, both for treatment and advice. Questions also investigated perceived barriers and promoters to referral and finally any preferences for referral between restorative specialists or mono-specialists.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for questionnaires were established before data collection. Exclusion criteria were questionnaires found to be incomplete, returned after the closing date or a respondent who was not a GDP currently practising in the Yorkshire region. There was also an option for subjects not wishing to complete the questionnaire. All valid questionnaire data was entered into SPSS 11 (for windows) by a single operator. Descriptive statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS.

Results

The overall response rate was 72% (217 questionnaires). Twenty-two of these responses were not included due to the exclusion criteria set prior to questionnaire release, this left 195 useable questionnaires for analysis.

The final sample to be analysed comprised of replies from 122 males (62.6%) and 73 females (37.4%). Respondents had qualified over a wide range of years. Practitioners working predominantly in the NHS made up 71.3% (n=139) of the sample and 28.7% (n=56) were predominantly private practitioners.

To assess current need and use of specialist restorative services, GDPs were asked to estimate how many NHS or private referrals they had made to each division of these services in the previous year (Fig. 3.)

When analysed as a whole, the majority of practitioners had sent few referrals in the previous year either in the NHS or private sectors. Prosthodontics received proportionally the least referrals per year, while NHS periodontics referrals were made most frequently, including almost one in five dentists (n=37) who sent three or more periodontal referrals in the previous year (19%).

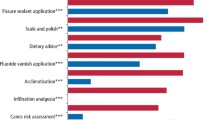

Participants were asked to give the top three reasons they thought would be most likely to make them refer more patients to the specialist restorative services (Fig. 4.) Similar results were obtained for both NHS and private patients, with medico-legal implications and increasing patient expectations being the most frequent answers in both cases (>73% GDPs chose these as their top three reasons (n=143)).

The questionnaire went on to ascertain barriers to referring NHS or private patients to each of the mono-specialities and the restorative speciality. The individual speciality results were all very similar and so were grouped together to assess the difference in barriers between NHS and private referrals (Fig. 5).

For the NHS referrals the most significant barrier was waiting lists being too long (79% of GDPs ranked this as one of their top three barriers (n=154)); this was a minor barrier for private referrals (14%, n=27). For private referrals the main barrier was high costs for the patient (88%, n=172); not a significant barrier for NHS referrals (20%, n=39). A major barrier for both NHS and private referrals was distance to a specialist centre (77% NHS (n=150), 69% private (n=135)). The final major barrier was the patient not being keen on referral (64% NHS (n=125), 66% (n=129) private). Over a third of GDPs rated being unsure if there was a certain type of specialist available in the area as a barrier to referral.

When asked if practitioners had a preference between a general restorative specialist and the appropriate mono-specialist there was a marked difference between the choices made for the NHS and private patient referrals. Fifty-eight per cent of GDPs (n=113) would prefer a private patient to see a mono-specialist, with only 5% (n=10) favouring a restorative specialist. With NHS patients the results were more balanced with 25% (n=49) preferring mono-specialists and 21% (n=41) restorative specialists (54% (n=105) did not express a preference).

The results were cross-analysed to assess possible relationships in the responses between the sexes or years of qualification of the participants. This indicated that the results were consistent across all sub-groups tested. After consultation with a statistician it was decided that descriptive analysis was most informative and that statistical tests were not indicated for results analysis in this study.

Discussion

The response rate to the questionnaire was acceptable at 72%. Following application of the exclusion criteria, a useable response rate of 65% was achieved. The sample was balanced both for year of qualification and sex distribution for the study population. The sampling method allowed the cohort to be stratified for location, thus providing a balance of urban and rural practitioners similar to that found in the Yorkshire Deanery. There was a mix of predominantly NHS (71.3%) and predominantly private practitioners (28.7%). Overall, just less than 20% of all practitioners in the Yorkshire Deanery were included in the data collected. As a result it was felt the study population was representative of dental practitioners in Yorkshire.

In terms of current referral patterns, most GDPs appear to refer very few individuals each year, although collectively there is clearly a high demand for specialist referral. When asked about factors that are likely to increase future referrals the most frequent answer was the increasing threat of medico-legal litigation (87% NHS/75% private.) The second most common reason cited for a potential increase in referrals was increasing patient expectations (73% NHS/88% private). Interestingly NHS practitioners rated medico-legal factors as their primary factor, whereas private practitioners rated increasing patient expectations as their highest single reason for an increase in referrals. In terms of the other possible responses, published referral guidelines would have a much greater influence on NHS referrals (51%) than for private referrals (33%). This is possibly due to the higher regulation of NHS dentistry in comparison with the private sector.

In terms of barriers to referral there was again a major difference in responses between NHS and private referrals. For NHS referrals the primary barrier was the length of waiting lists (79%), whereas the principal barrier to private referrals was the expense of treatment (88%). Major factors that were common to both NHS and private referrals were the distance to the referral centre and the patients' reluctance to be referred. This would appear to indicate a need for local specialist centres or out-reach clinics and increased patient education on the benefits of specialist treatment and advice. One in three participants reported being unsure whether a specialist was available in their area as being a significant barrier to referral. This shows a need to tell practitioners about the services available to them. This is a key issue, as the GDC expects practitioners to be able to make appropriate referral decisions quickly, mindful of the best interests of the patient.11,12

The potential promoters and barriers to referral used in this study are comparable with those posed by Morris and Burke in 2001, when they looked at the interface between primary and secondary dental care.13 This study has been able to assign a degree of importance of each of these factors as perceived by general dental practitioners.

When asked if practitioners had a preference for an appropriate specialist or a general restorative specialist there was again a marked difference between NHS and private referrals. For private referrals the majority of practitioners (58%) would prefer referral to the appropriate mono-specialist. This was in contrast to NHS referrals for which most practitioners had no preference (54%.) Although most the questions were of a closed response format, there was an optional open response question relating to why GDPs had a preference. A third of the responding sample gave reasons for their preference. These mostly revealed a high regard for the focused skills of mono-specialists, although a smaller number of GDPs preferred restorative specialists as they may have the benefit of being able to 'see the bigger picture'. It would seem overall, that a mono-specialist or a restorative specialist with a preference in one mono-speciality may be perceived as the ideal person to refer to.

A final interesting observation from the study was that the reported demand was least for the prosthodontic specialty, yet this discipline has the greatest number of practitioners registered on its specialist list and of the mono-specialities, the largest number currently on its training programmes.

Conclusions

From the results it would seem that there is a strong demand for referrals to the restorative specialist services, which may increase in the future due to increasing pressure on GDPs to seek a specialist opinion. The questionnaire indicated a high regard for mono-specialists suggesting that they are already well respected within the profession. Although promoters for NHS referrals differ slightly compared with private referrals, there seems to be an overall consensus of opinion demanding a prompt, locally based, referral service at an affordable cost. This study should provide useful information for those responsible for planning future provision of specialist restorative services, for practitioners who are considering specialist training and also for specialists currently working in NHS and private dentistry.

References

The Faculty of Dental Surgery. Specialisation in dentistry: A practical g. The Royal College of Surgeons of England, 1999.

Smith BGN . The road to specialisation. Dent Update 1998; 25: 397–399.

Callis PD . The new MFDS/MFD examination. Br Dent J 1998; 185: 308–310.

General Dental Council. http://www.gdc-uk.org/searchspec.html (Accessed on 18/08/03)

Woodman AJ . Who wants to be a specialist? Personal view. Br Dent J 1998; 184: 312.

Basker RM, Harrison A, Ralph JP . A survey of patients referred to restorative dentistry clinics. Br Dent J 1988; 164: 105–108.

Falcon HC, Richardson P, Shaw MJ, Bulman JS, Smith BGN . Developing an index of restorative dental treatment need. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 479–486.

Brook PH, Shaw WC . The development of an index of orthodontic treatment priority. Eur J Ortho 1989; 11: 309–320.

Dowie R . A review of research in the United Kingdom to evaluate the implementation of clinical guidelines in general practice. Fam Pract 1998; 15: 462–470.

The Department of Health “The NHS Plan 2000 www.dh.gov.uk/policyandguidance/organisationpolicy/modernisation/fs/en Accessed on 03/10/02 (updated 28/07/00).

Department of Health. Modernising NHS dentistry – Implementing the NHS plan. Department of Health, 2000

Morris AJ, Burke FJT . Primary and secondary dental care: the nature of the interface. Br Dent J 2001; 191: 660–664.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr J. P. Ralph (Former Dean of Postgraduate Dental Education, Yorkshire) for advice and financial support for the project. Thanks also to Phoebe Mercer (Research officer, Dental Postgraduate Research Department) for her assistance and to Dr J. Pedlar and Mr A. Blance for their statistical advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nixon, P., Benson, R. A survey of demand for specialist restorative dental services. Br Dent J 199, 161–163 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812577

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812577

This article is cited by

-

Novel tier 2 service model for complex NHS endodontics

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Dental specialist workforce and distribution in the United Kingdom: a specialist map

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

An investigation into how general dental practitioners in Leeds manage complex tooth wear cases

British Dental Journal (2020)

-

Clinical and academic recommendations for primary dental care prosthodontics

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

Dentists with enhanced skills (Special Interest) in Endodontics: gatekeepers views in London

BMC Oral Health (2015)