Key Points

-

As part of a group audit, prospective data have been collected on the reasons for tooth extraction in general dental practice.

-

Variability was observed in the number of teeth extracted by surgeon.

-

More teeth were extracted for caries in the most deprived group.

-

Equitable services were delivered collectively by the audit group.

Abstract

Tooth retention has been one of the main aims of oral care which in turn could have contributed to the social oral health divide. To investigate this issue further, data collected for a group audit was used to study the reasons for tooth extraction for patients attending for routine treatment at four dental practices. The practices served populations in areas with different levels of deprivation in South Wales. In 558 teeth extracted over 417 visits, the reasons for extractions were: caries 59%, periodontal disease 29.1%, pre-prosthetic 1%, wisdom teeth 4.6%, orthodontic 5.5%, trauma 1.2%, patient request 2.4% and 6.2% other reason. The number of extraction visits per day within the group of dental surgeons varied with three practitioners performing more than three extraction visits per day while one practitioner had only 0.51. These reasons did not significantly depend on levels of deprivation. However, significantly more teeth were extracted for caries in the most deprived group in comparison to the least deprived. Therefore, could there be a case for appropriate extractions in the quest for equitable care?

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Tooth-loss is in decline in the United Kingdom. It is predicted that only 6% of the population will be edentate by the year 2028.1 It is also suggested that the analysis of tooth mortality statistics is important in evaluating dental care , implying that tooth mortality in dentistry is analogous with mortality statistics in the medical field.2 Encouraging statistics show that life expectancy is increasing and so is the dentate population.3,4,5

Disease specific risk factors for tooth-loss include mostly caries and periodontal disease, with ongoing debate on whether caries or periodontal disease is the main cause of tooth-loss. Other causes of tooth-loss include the sequelae of caries and periodontal disease, orthodontic treatment, traumatic injury to the teeth, prosthetic treatment and symptomatic wisdom teeth.

Professional treatment decisions for tooth-loss can be described under three headings: micro, meso and macro. On the individual (micro) level, the dental surgeon will assess the patient's needs and act accordingly. On the organisational (meso) level, the dental surgeon will provide services according to the system in which the organisation functions, for example the NHS terms of service, the community service, private practice, insurance systems and Personal Dental Services (PDS). This will affect the availability and accessibility to services for sub-groups in the community.6 On the population (macro) level, demographic variables including age, attendance patterns, anxiety and socio-economic status are associated with tooth-loss.

It is well documented in the literature that there are inequalities in toothlessness in adults of different socio-economic backgrounds.1,2,3,4,5 For example, in Wales, the percentage of edentulous adults in the higher social classes (I II and III Non-manual) was 10% and in the lowest (IV and V) 24%. This division is also seen in UK statistics.5

Few studies have assessed the reasons for tooth extraction based on social class diversities.2,7,8 Tickle et al.9 studied inequalities in the dental treatment provided to children. No significant association was found between socioeconomic status and caries experience of frequently attending children. However, disadvantaged children were significantly more likely to have teeth extracted than their affluent peers. It is therefore suggested that inequity exists in the prescription of dental care with regard to tooth extraction, showing varying preferences of their dentists and patients. Worthington et al.10 studied regularly attending adults to assess factors that are predictive of tooth-loss. In that study, both the dentists' and patients' perceptions of need for dental treatment were significant predictors of tooth extraction.

This study aimed to answer three questions:

-

Why are teeth extracted?

-

Are the reasons for extraction different within different social groups?

-

Are the reasons for extraction different according to dental surgeon?

The Audit Data

Ethical approval was obtained from the University Ethics Committee. A cross-sectional survey was conducted in the summer of 2002 as a data collecting exercise for an audit of tooth extraction. Eight dentists from four dental practices in two geographical locations in South Wales collected data on patients (n=397) attending for dental extractions. Three of the practices were in Swansea and one in Pontypridd. The data were collected for 100 consecutive extraction visits over a period of two months (July and August 2002) whichever was achieved first. In this, the following strategies were adopted:

-

Each surgeon was allocated a number for his/her surgeon code;

-

Some practices with numerical filing systems used their patient number while others without numerical filing systems used consecutive numbers for recording patients. Both scenarios are listed under the same variable name:

-

Actual teeth extracted could also be recorded;

-

The primary reason for the tooth/teeth extraction(s) was established and whenever available, a secondary reason was also documented;

-

Ambiguous reasons for the tooth/teeth extraction(s) were described under 'other';

-

Any patient of age 13 years or less was categorised as a child.

The reasons for tooth extraction were based on the criteria proposed by Kay and Blinkhorn11 (caries, periodontal disease, pre-prosthetic reason, orthodontics, trauma, wisdom teeth, patient request and other reason).

The patient postcode was noted and categorised by the Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD).12 The IMD is a combination of more specific forms of deprivation, which can be more or less directly measured. These include the domains of income, employment, health, education, housing and geographical access to services. Using electoral divisions, a score has been allocated for each of the above domains to each electoral division. Each of the divisions in Wales were scored, ranked and grouped into quintiles (a relative frequency of 20% each). The corresponding relative IMD frequencies for our sample and its corresponding population are given in Table 1. A test of uniformity between the two frequencies within each of the IMD groups revealed no significant difference. This is an indication that the patients are proportionally representing the population that they came from in terms of their IMD groups. In examining tooth extraction by different IMD groups, assuming that 20% of those in the affluent sector have tooth extraction while 30% of the corresponding proportion is in the deprived sector, a sample of 100 from the latter would allow the identification of significant differences between the two groups at a 95% level with 70% power. A sample of 150 would increase the power of the test to 87%.

Reasons for tooth extraction are displayed together with the frequency of their occurrences. The IMD is correlated with the number of patients requiring extractions. Reasons for the possible relationship between tooth-loss and each of the IMD and surgeon factors were examined using Chi-squared test of independence. One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to examine whether the causes of extraction vary according to level of deprivation, or by surgeon.

Findings

Five hundred and fifty eight teeth were extracted over 417 visits. Within the audit time frame, 18 patients had more than one visit for extractions. On average, 1.33 teeth were extracted per visit with 12.6% of extraction visits for children born after 1990. The dental surgeons worked 222.5 days with an average of 1.9 extraction visits per day. Table 2 shows the number of extraction visits and the number of extraction visits per day for each surgeon.

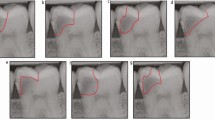

Of the 417 patient visits recorded, 397 had valid postcodes for analysis. The number of patients increased with level of deprivation (Fig. 1). This correspondence is represented by a correlation of 0.842 with a significance of p=0.074.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of children according to deprivation status. In this, it was established that over 60% (n=32) who were within the IMD bands 4 and 5, experienced tooth extraction while only 21% (n=11) within the IMD bands 1 and 2 experienced tooth extraction. Fifteen percent (n=8) of the total 52 children were in IMD band 3.

The majority of the patients had only one tooth extracted per visit (Fig. 3), with no significant difference emerging between social groups for the number of teeth extracted (p=0.058).

The reasons for extraction(s) are shown in Table 3. The results are presented based on the reason for the first tooth removed. Figure 4 shows the primary and secondary reasons for extraction. Further investigation of the data revealed that patient request accounted for 37% (n=84) of the reported secondary responses. Out of the latter identified responses, 53.3% were from the most deprived group.

The reasons for tooth extraction by different levels of deprivation are shown in Table 4. Due to cells in the analysis having expected counts of less than five, the reasons were regrouped into caries, perio and 'grouped reasons' (Table 5) with the latter representing all reasons with small frequencies. Chi-squared test of independence did not lead to any significant dependence between the regrouped reasons and the IMD (p=0.121).

Using the results obtained in Table 5, Analysis of Variance (one way ANOVA, F=3.313. df=2, p=0.037) revealed significant differences between the regrouped reasons for extraction within different deprived groups. Sixty one percent from the 'most deprived' had extractions because of caries compared with 44.8% from the 'least deprived'. Conversely, 32.8% from the 'least deprived' had extractions for 'other' reasons compared with 15.5% from the 'most deprived'.

To compare the reasons for tooth extraction between dental surgeons, the independence between reasons for extraction and dental surgeon was examined. Table 6 shows the regrouped reasons for tooth extraction by dental surgeon. Even after this regrouping, two of the cells had expected counts relating to surgeon number 4 of less than five and hence, a test of independence was unreliable to extrapolate.

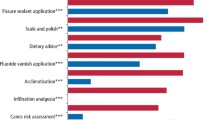

Using the results obtained in Table 6, Analysis of Variance (ANOVA, F=0.687, df=2, p=0.503) revealed no significant difference between different surgeons in their tooth extractions. However, on a more detailed level, when all reasons were considered, different surgeons were found to differ significantly in their practise (ANOVA, F=2.635, df=7, p=0.011). Only 5% of surgeon 4's extractions were for periodontal disease while for all other surgeons, periodontal disease accounted for over 10%. Surgeon 6, on the other hand, had the highest percentage (33%) for the same reason. Surgeon 5 had 25% of extractions for orthodontic reasons while the remaining surgeons were at 8% or less for the same reason.

Concluding remarks

The primary aim of the study was to explore the reasons for tooth extraction within different social groups. However, before doing so, it is important to highlight some methodological features of the study. Unlike many reported studies, this study collected data prospectively. The sample used in the study was a convenience sample of those patients consecutively attending four general dental practices in South Wales for tooth extractions. It was not possible to categorise 20 of the subjects by the IMD due to inaccurate recording of postcodes. The matching rate compared favourably with other studies involving GIS (Geographical Information Systems). The accepted limitations of GIS studies have been documented.13,14 Analysis of the missing data showed similar trends to the overall sample suggesting that the missing data did not create any bias in the results.

Caries was, by far, the major reason for tooth extraction in the sample studied. This is in accordance with the results published by other researchers.2,15 The current research was an investigation of disease specific reasons for tooth extraction. The aim was not to support the findings that caries is the major reason for tooth-loss in all age groups as the data collection was restricted to two groupings of adults and children only. Even though the number of teeth extracted because of caries far exceeds periodontal disease, it is not possible to conclude the controversial debate on whether caries is the major reason for tooth-loss in older adults.

No significant dependence could be established between reasons for tooth extraction and levels of deprivation. This would suggest that the increasing preference for extraction, rather than restorative treatment, was not linked to deprivation status. This is in accordance with other published work.11,7,2 However, the results of the latter study have been criticised by its authors for potential bias due to the possibility of the sample being recruited from the lower socio-economic backgrounds.2 The results of the current study also suggest caution in the above conclusion despite the inclusion of patients from affluent areas. Significant differences were observed between the reasons for extraction within deprived groups with relatively more extractions in the affluent groups in the 'grouped reasons' category and relatively fewer extractions in the affluent groups in the caries category. Extractions in the 'grouped reasons' category included wisdom teeth extractions, orthodontic extractions, trauma, patient request and 'other'. Extractions in the 'other' included retained deciduous teeth, root fractures following restorative care, failed root treatments and erupting teeth under full dentures. These reasons, with the exception of patient request, are not associated with their preference for extraction. Over half of those who requested tooth extraction as a secondary request came from the most deprived group.

The number of extractions per visit was not significant at the 95% confidence level for different social groups (p=0.058). However, at the 94.2% confidence level there was a significant difference. It would be expected for individuals with increased levels of disease to have more episodes of multiple extractions. This would be in accord with accepted trends in oral health.16

A two-month time frame was used to assess the number of extraction visits undertaken. Only one practitioner achieved 100 consecutive extraction visits within this time frame. However, three practitioners performed more than three extraction visits per day. The variability in numbers of extraction visits per day within the group of dental surgeons probably reflects the demography of their practice profiles. Of course, dental surgeon decision-making must also be considered in accounting for this result. The varying preferences and built-in preconceptions about how different groups of patients should be cared for have been eluded to (Tickle et al.9 for children and Worthington et al.10 for adults). The results from this small study suggests that further research is necessary to investigate this issue.

The reasons given by the dental surgeons have not been validated and therefore could reflect the subjectivity of clinical decision-making. This was particularly so for surgeon 4 and 6 with low and high levels of extractions as a result of periodontal disease. We must also accept that it is possible that these clinicians treated less/more patients with periodontal disease. Surgeon 4 practised within the confines of an organisation with individuals of more affluent backgrounds and a younger population which could possibly account for low levels of periodontal disease. Surgeon 5 reported abnormally high attendance for orthodontic extractions within the time frame allocated for data collection. This could be due to the time of year and school holidays.

The disease specific risk factors identified in this study are similar to other published surveys in the UK.17,18 In the context of a consecutive sample of patients rather than a random sample drawn from the population, the number of extractions increased with increased levels of deprivation. The collective data from the practice sites showed no differences between the reasons for extractions and deprivation groups using Chi-squared goodness-of-fit tests. This suggests equitable micro and meso professional treatment decisions with regard to tooth loss collectively in the audit group.

Whether this audit group is representative of general practice in the UK is not known. Disease specific risk factors and patient preference may account for the differences observed using ANOVA. Whether macro professional treatment decisions impact on disease specific risk factors is an interesting question for further research.

References

Todd JE, Lader D (1991) Adult Dental Health Survey 1988. London: HMSO.

Cadlas AF, Marcenes W, Sheiham A. Reasons for tooth extraction in a Brazilian population Int Dent J 2002; 50: 267–273.

Summerfield C, Babbs P. National Statistics Social Trends No 33 2003. London: TSO.

Insalaco R. Annual Abstract of Statistics No 138 2002. London: The Stationary Office.

Kelly M, Steele J, Nuttall N et al. Adult Dental Health Survey - Oral Health in the United Kingdom 1998 2000. London: The Stationary Office.

Tickle M, Blinkhorn AS, Brown PJB, Mathews R. A geodemographic analysis of the Denplan patient population in the North West Region. Br Dent J 2000; 189: 494–499.

Thomas DW, Satterthwaite J, Absi EG, Shepherd JP. Trends in the referral and treatment of new patients at a free emergency dental clinic. Br Dent J 1997; 182: 11–14.

Locker D et al. Incidence of and risk factors for tooth loss in a population of older Canadians. J Dent Res 1996; 75: 783–789.

Tickle M, Milsom KM, Blinkhorn AS. Inequalities in the dental treatment provided to children: an example from the UK. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2002; 30: 335–341.

Worthington HV, Clarkson JE, Davies RM. Extraction of teeth over five years in regularly attending adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1999; 27: 187–194.

Kay EJ, Blinkhorn AS. The reasons underlying the extraction of teeth in Scotland. Br Dent J 1986; 160: 287–290.

National Assembly for Wales (2000) Welsh Index of Multiple deprivation 2000 Edition Cardiff: National Assembly for Wales.

Higgs G, Richards W. The use of geographical information systems in examining variations in sociodemographic profiles of dental practice catchments. A case study of a Swansea practice. Primary Dental Care 2002; 9: 63–65.

Gatrell AC. On the spatial representation and accuracy of address-based data in the United Kingdom. Int J Geograph Information Systems 1989; 3: 335–348.

McCaul LK, Jenkins WMM, Kay EJ. The reasons for extraction of permanent teeth in Scotland: a 15 year follow-up study. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 658–662.

Murray JJ, Pitts NB. Trends in oral health. In: Community Oral Health 1997. Ed. Pine CM. Oxford: Wright.

Agerholm DM, Sidi AD. Reasons given for the extraction of permanent teeth by general dental practitioners in England and Wales. Br Dent J 1988; 164: 345–348

Hull PS, Worthington HV, Clerehugh V et al. The reasons for tooth extractions in adults and their validation. J Dent 1997; 25: 233–237.

Acknowledgements

The practitioners who took part in the audit which provided the data for this research are thanked. The audit was funded by the Welsh Assembly through CAPRO.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Richards, W., Ameen, J., Coll, A. et al. Reasons for tooth extraction in four general dental practices in South Wales. Br Dent J 198, 275–278 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812119

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812119

This article is cited by

-

Analysis of split tooth as an unstudied reason for tooth extraction

BMC Research Notes (2014)

-

The effect of prosthetic margin location on caries susceptibility. A systematic review and meta-analysis

British Dental Journal (2013)

-

Optimization of quantitative polymerase chain reactions for detection and quantification of eight periodontal bacterial pathogens

BMC Research Notes (2012)

-

Reasons for extractions, and treatment preceding caries-related extractions in 3–8 year-old children

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (2010)