Key Points

-

Current policy changes provide opportunities for the role development of dental technicians within the dental team.

-

Factors relating to job satisfaction of dental technicians are explored.

-

Many dental technicians feel insufficiently valued in the dental team.

-

Only a minority of dental technicians expect to develop their careers over the next five years.

-

Factors influencing the low levels of continuing professional development undertaken are discussed.

Abstract

Objective To investigate the career development, perception of status within the dental team, and level of job satisfaction of dental technicians in the United Kingdom.

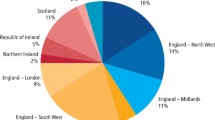

Design Cross-sectional postal questionnaire survey of 1,650 dental technicians registered with the Dental Technicians Association. Replies were received from 996 (60%).

Results Eighty two per cent respondents had a qualification in dental technology and 21% also had an advanced level qualification. Almost two thirds of the respondents had undertaken no verifiable continuing professional development in the previous year. Only 27% of respondents expected to develop their career over the next five years. Less than 50% of the respondents felt adequately valued as individuals and as a professional group in the dental team. Job satisfaction was significantly related to age, attendance at one or more courses in the last year, working shorter hours, feeling valued in the dental team, and future career plans.

Conclusions Plans for the registration and role expansion of dental technicians provide opportunities for career development which have yet to be realised. The low levels of continuing professional development currently undertaken indicate the need for a review of the provision and funding of training at a strategic level. Whilst levels of job satisfaction are satisfactory, many dental technicians feel insufficiently valued in the dental team.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The preparation for statutory registration of all professionals complementary to dentistry (PCDs) by the General Dental Council (GDC)1,2,3,4 has prompted an increased interest in the working practices, career progression and job satisfaction of PCDs in the published literature.5,6,7,8 The statutory registration of PCDs occurs against the backdrop of a number of recommendations that the roles of PCDs should be expanded.9,10,11 These proposals are developed in Options for Change12 which promotes the ethos of teamwork in primary dental care and suggests ways of developing the roles of PCDs within the extended dental team.

In contrast to the attention given in the published literature to dental nurses, hygienists and therapists, there is little or no literature on the professional career development, working practices and job satisfaction of dental technicians.

The term 'dental technician' currently covers a wide umbrella of experience, education, training and expertise. There are an estimated 10,000 dental technology workers in the UK13,14 of which as many as 70% are unqualified laboratory assistants or process workers.15 After statutory registration with the GDC is introduced in 2004, only qualified dental technicians or those with 7 years' experience in the last 10 years will be able to call themselves 'dental technicians'.16 The GDC envisages that through continuing professional development (CPD) and modular training provision, dental technicians will be able to extend their range of skills.1,17 With additional approved training, clinical dental technicians would be able to take impressions and provide and fit dentures for patients on the written prescription of a dentist.

Most dental technicians work in commercial laboratories although some work in general dental practice, the community dental service, hospitals, universities and the armed forces.18 A recent survey undertaken by LCS International Consulting Ltd (LCS) on behalf of the Dental Laboratories Association (DLA)19 estimates that the total size of the UK dental laboratory sector at the end of 2002 was approximately £290-295 million of which about 28% was private work. Growth is occurring in the private sector as demand for new products such as implants, Belleglass composite resin crowns, Procera crowns, fibre reinforced crowns and bridges etc increases.

The LCS survey highlights growing problems in the NHS sector. Turnover per technician in NHS laboratories is £52,500 per annum, compared with just over £65,000 per annum in laboratories providing mainly private work and this is reflected in technicians' salaries which are 30% higher in the private sector. There are particular problems recruiting and retaining qualified dental technicians in the NHS sector, and NHS laboratories do not have access to capital to invest in new equipment and products, or in education and training. NHS laboratories often only distinguish their products on a price basis with very low weighting being given to quality and reliability.

Other surveys have examined education and training.20,21 The most recent survey of dental technician education and training in the UK21 reveals the lack of a national training strategy, poor funding for training, a fall in the number of training places for dental technicians related to a reduction in the number of training centres and uneven geographical distribution of training centres. Just over 100 dental technicians achieved the BTEC National Diploma in 2001 which is the lowest number since 199222 and is far short of the 700 per year required to sustain the current level of manpower in the industry, as estimated by a joint committee of the DLA and the Dental Technicians Association.15

Whilst these surveys provide some details about the financial state of the dental laboratories, working practices of dental technicians, and education and training provision, there is no information in the published literature on the professional career development of dental technicians, their perception of status within the dental team and job satisfaction, all of which are fundamental to the planning and success of the further integration of dental technicians into the dental team and the envisaged expansion of their roles.

This study seeks to explore the professional career development, perception of status within the dental team, and job satisfaction of dental technicians registered with the Dental Technicians Association (DTA).

Method

A postal questionnaire survey of all dental technicians registered with the DTA was carried out (n = 1,650). The DTA is the largest body of dental technicians in the UK and maintains the only UK National Register for Dental Technicians, entry to which is voluntary and is dependent on achieving a BTEC national diploma in Dental Technology (or equivalent) or having 7 years' experience. The title 'dental technician' includes dental technicians who are working in related roles, for example laboratory managers, university tutors, lecturers, demonstrators, commercial representatives etc. Specialist technicians such as maxillofacial prosthetists have their own associations and are not included in this survey unless they have additional registration with the DTA.

Questionnaire

The structured questionnaire developed for this study was based upon the adaptation of a questionnaire used in recent surveys of the career development and job satisfaction of general dental practitioners, dental therapists, and dental hygienists.5,6,7 The content and wording of the questionnaire were modified following consultation with the DTA. The questionnaire was then piloted on a small number of dental technicians registered with the DTA to ensure clarity. The questionnaire included sections covering the following areas:

-

Demographic characteristics of respondent

-

Working hours

-

Continuing education

-

Job satisfaction

-

Status in the dental team

-

Plans for career development.

Procedure

A copy of the research questionnaire was sent to each participant together with a cover letter explaining the purpose of the research and a reply paid envelope. The initial mailing took place in May 2002 and was followed shortly afterwards by a second mailing to target non-respondents. All questionnaires were answered anonymously.

Data entry and analysis

The coded responses were entered onto SPSS version 10.0. Analysis was mostly restricted to descriptive statistics, but the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare levels of job satisfaction for the following groups: male and female dental technicians, technicians above and below the median age of the sample, and technicians who had attended courses (in-house or external) in the last year compared with those who had not. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was used to assess the association between satisfaction levels and working hours, and between satisfaction levels and perception of being valued in the dental team. The Chi-square test was used to test for significant differences in satisfaction levels according to future career plans.

Non-respondents

A comparison of the characteristics of the respondents with the non-respondents was not possible as data held by the DTA are not in the public domain and are therefore subject to the requirements of the Data Protection Act 1998. However, a comparison of the characteristics of the early and late respondents was carried out using the Chi-square and Mann-Whitney U tests.

Results

Characteristics of the respondents

Replies were received from 996 dental technicians (response rate 60%). Respondents comprised 871 males (87%) and 123 females (12%); data on gender not available for 2 respondents. The average age of the dental technicians was 45.6 years (SD = 12.7). A total of 389 individuals (39%) indicated that they had childcare responsibilities.

Eight hundred and twenty one (82%) respondents held a basic level qualification in dental technology, the most common of which were the Dental Technicians' Final Certificate of the City and Guilds of London Institute, and the BTEC National Diploma in Dental Technology. Of the qualified respondents, 212 (21%) also held an advanced level qualification in dental technology, including 17 (2%) who held a degree specific to dental technology. One hundred and forty one (14%) respondents also stated that they had other qualifications and experience relevant to their work as a dental technician. The average number of years since qualification was 24.7 years (SD = 13.3).

One hundred and fourteen (11%) respondents were not currently working as dental technicians. Of these, 33 (3%) were in other paid employment, 57 (6%) had taken a break from their career, the most commonly cited reasons being personal illness (13 respondents) and study (10 respondents), and the remainder had retired.

A comparison of the characteristics of the early (n = 638) and late (n = 358) respondents indicated no significant differences other than the finding that 27% of the late respondents had no formal qualifications, compared with 18.5% of the early respondents (Chi-square = 4.86, P = 0.027).

All descriptions of findings from this point forward are concerned only with those respondents who are currently practising as dental technicians (n = 882).

Working hours

Respondents were asked to indicate the number of hours they had worked in the previous week. Table 1 indicates that the majority of dental technicians were working in excess of 40 hours per week and 248 (28%) were working more than 50 hours per week. Only 61 (7%) were working part-time (defined as fewer than 30 hours per week). Seventy-one (8%) respondents had other jobs in addition to their work as a dental technician.

Continuing professional development

The Dental Technician was the most popular professional journal among dental technicians with 691 (78%) having read it in the last three months. Table 2 shows the total number of respondents who reported reading various professional journals in the past three months. Sixty-six (7%) respondents had not read any professional journals during this time.

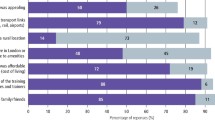

Respondents were asked to indicate their attendance at in-house training or external courses in the last year. Table 3 shows a breakdown of the time spent at training days and Fig. 1 indicates the type of course attended. Almost two thirds of the respondents had not attended any courses in the previous year.

Only 21 (2%) of all respondents had taken or were taking a career break for study purposes indicating that the vast majority of professional development is integrated into working life.

Status in the dental team

Using a five-point Lickert scale, respondents were asked to rate whether they felt that they were a valued part of the dental team. They were also asked to rate whether they felt that dental technicians as a group are considered to be a valued part of the dental team. The results are shown in Table 4 Dental technicians had a higher perception of their value as an individual in the dental team than their perception of the value of dental technicians as a group. However, in both instances, less than half of the respondents felt adequately valued in the dental team (as defined by indicating that they felt valued most or all of the time).

Job satisfaction

Respondents were asked to rate their satisfaction with their work life on a ten-point scale with anchors of 1 = minimum satisfaction and 10 = maximum satisfaction. The results are shown in Fig. 2 Levels of job satisfaction were high; 442 (50.4%) respondents rated their job satisfaction at a score of 8 or more. The mean value of job satisfaction was 6.99 (SD = 2.3) and the median value was 8.

Levels of job satisfaction were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test for the following groups: male and female dental technicians, technicians above and below the median age of the sample, technicians who had attended courses (in-house or external) in the last year versus those that had not. All of the groups showed significant differences in job satisfaction with the exception of male and female dental technicians. Dental technicians aged 45 years and over were on average more satisfied with their work life (median satisfaction = 8) than those aged 44 years and under (median satisfaction = 7); Mann-Whitney U = 75977, P ≤ 0.001. Those technicians who had attended any courses in the last year were on average more satisfied with their work life (median satisfaction = 8) than those who had not (median satisfaction = 7); Mann-Whitney U = 77183, P = 0.002 (external courses), Mann-Whitney U = 55314, P = 0.004 (in-house training).

Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was used to assess the association between satisfaction levels and perception of being valued in the dental team (individual and group), and between satisfaction levels and working hours. A significant positive association between satisfaction levels and perception of being a valued part of the dental team was found (rs = −0.487, P ≤ 0.001). A significant positive association between satisfaction levels and perception of dental technicians as a group being valued in the dental team was also found (rs = −0.284, P ≤ 0.001). A significant negative association between satisfaction levels and working hours was also found (rs = −0.082, P = 0.016).

Plans for career development

When asked about future plans, just less than half of the respondents (44%) felt that they would be in their current job in five years and 77 (9%) felt that they would be in a better job with their current employer. A total of 161 (18%) hoped that they would have bought their own laboratory. For the 31.5% respondents planning to leave the workforce in the next five years, 187 (21%) respondents said that they would have retired in five years, 81 (9%) felt that they would be in another career, and 13 (1.5%) hoped to be working overseas.

There were significant differences in satisfaction levels according to future career plans (Table 5), with those hoping to be in another career showing the lowest job satisfaction levels (mean = 4.98, median = 5) and those planning to be retired indicating the highest job satisfaction levels (mean = 7.57, median = 8), Chi-square = 134.41, P ≤ 0.001.

Early and late respondents

A comparison of the data of the early and late respondents yielded no significant differences in any of the areas covered by the survey other than the issue of feeling valued as an individual in the dental team. The late respondents felt marginally more valued in the dental team than the early respondents (Mann Whitney U = 81098.5, P = 0.047) but there were no significant differences found in the perception of dental technicians being valued as a group.

Discussion

This study reports the findings of a survey of the professional career development, job satisfaction and perception of status in the dental team of all dental technicians registered with the DTA in May 2002.

The external validity of the findings is compromised by the fact that the only register of dental technicians available represents a mere sixth of the UK workforce.13,14 Even when all dental technicians are registered with the GDC, unqualified process workers who make up to 70% of the workforce will still not be registered unless there are further changes in legislation and thus they will remain a silent and invisible part of the dental technology workforce.22

Furthermore, the response rate of 60% raises the possibility of non-response bias. The response rate was lower than that of similarly conducted surveys of dental therapists and hygienists (80% and 64% respectively) undertaken by the same research team.5,6 However, when compared with the low response rates of the recent LCS surveys, for example 18.5% in the 2001/2 survey,14 which are the other main source of information about the dental laboratories sector, the response rate of this survey is far better. Whilst it was not possible to compare the characteristics of the respondents with the non-respondents, a comparison of the data of the early and late respondents revealed no significant differences other than a suggestion that the late respondents were less qualified but felt marginally more valued as individuals in the dental team. Nonetheless, because of these differences, generalisation of the findings should be undertaken with a degree of caution.

In spite of these limitations, the survey provides a valuable insight into the views and experiences of qualified and/or experienced dental technicians.

The study demonstrates that nearly two thirds of the respondents are not attending any courses and are therefore unlikely to fulfil verifiable continuing professional development (CPD) requirements following registration with the GDC.16 This may be due to a variety of reasons. As most dental technicians are not working within the mainstream NHS, they do not have access to NHS funds for training and development.15 The LCS 2001/2002 survey14 indicates that laboratories spend on average only 1.1% of turnover on training. The survey also indicates that the main challenge facing laboratories is the meeting of production deadlines, particularly in the NHS sector, which together with long working hours means that CPD may be given a lower priority.

There are little data on availability of suitable courses. Whilst other surveys have identified a shortage of training places for the attainment of formal qualifications,20,21 it is clear that there is an urgent need to also examine the provision and funding of courses for CPD purposes at a strategic level. A partnership between employers, manufacturers, professional bodies, dental hospitals, higher education and further education colleges has been suggested as one way forward for developing education and training for dental technicians.15,23

The perception of poor career prospects24 may also be a factor in low levels of CPD activity. This survey indicates that only 27% of respondents expected that their career as a dental technician would develop over the next five years, the majority indicating that they planned to own their own laboratory. None of the respondents suggested that they planned to undertake further training to become clinical dental technicians.

If dental technicians have a perception of poor career prospects, one might expect that job satisfaction levels would be low, particularly given reports of other problems such as low pay and investment levels, fees for NHS laboratory items being driven down, and long working hours.14,15,19,24 However, high levels of job satisfaction are expressed. Whilst it is possible that the findings may not be fully representative, given the limitations of the sampling frame and the response rate, it is also plausible that many dental technicians are content with their working lives and do not wish to develop their careers along the lines suggested by the GDC.

It should be noted however, that a small proportion (10%) of dental technicians expressed very low levels of satisfaction, scoring 1–3 on the satisfaction scale, and 8% of respondents planned to be in another career in five years' time.

For those who do wish to develop their careers, plans for registration and role development of PCDs provide dental technicians with an unprecedented opportunity to expand their career prospects and negotiate investment in training and development.

The positive association between job satisfaction and the perception of being valued as an individual in the dental team, and the perception of being valued as a professional group in the dental team is to be expected. The General Dental Council's proposals for registration of PCDs and Options for Change share a clear vision of the dentist as leader of a well integrated team of PCDs providing primary dental care. This survey indicates that whilst many dental technicians feel valued as part of the dental team, more than half do not feel sufficiently valued and most dental technicians do not perceive their professional group to be adequately valued in the dental team.

It has been suggested that the geographical separation between dental surgery and laboratory compounds the problem,9 but research also indicates other issues such as persistently poor written communication between dentists and technicians25,26 and it has been suggested by dental technology tutors that dentists have little interest in the education and training of dental technicians.21 In addition, many technicians perceive that the low NHS fees for dental laboratory items reflect a low value placed on dental technical work by the Department of Health.9

The benefits of better integration of dental technicians into the dental team in terms of improved patient care and job satisfaction cannot be overstated. It is in the interests of both dentists and dental technicians to actively seek to improve their relationship, particularly in view of current government policy changes. The radical changes in the way NHS primary dental care will be funded, as outlined in the Health and Social Care Bill,27 will possibly create a window of opportunity for both dentists and dental technicians to negotiate better funding for NHS dental technical work although this may have to occur at the Primary Care Trust level.

References

General Dental Council. Professionals complementary to dentistry. London: GDC, 1998.

General Dental Council. Regulating all members of the Dental Team. London: GDC, 2001.

General Dental Council. A statutory framework for regulation of all members of the dental team. London: GDC, 2002.

General Dental Council. Developing the dental team: curricula frameworks for registrable qualifications for professionals complementary to dentistry (PCDs). London: GDC, 2003.

Gibbons DE, Corrigan M, Newton JT . The working practices and job satisfaction of dental therapists: findings of a national survey. Br Dent J 2000; 189: 435–438.

Gibbons DE, Corrigan M, Newton JT . A national survey of dental hygienists: working patterns and job satisfaction. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 207–210.

Newton JT, Gibbons DE . Levels of career satisfaction amongst dental healthcare professionals: Comparison of dental therapists, dental hygienists and dental practitioners. Community Dent Health 2001; 18: 172–176.

Sprod A, Boyles J . A survey of the training needs of PCDs in the GDS. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 389–397.

Nuffield Foundation. Education and training of personnel auxiliary to dentistry. London: Nuffield Foundation, 1993.

Dental Auxiliary Review Group. Report of the dental auxiliaries review group. London: BDA/JM Consultancy Ltd, 1998.

Department of Health. Modernising NHS Dentistry: implementing the NHS plan. London: Department of Health, 2000.

Department of Health. NHS Dentistry: Options for Change. London: Department of Health, 2002.

The Dental Technician. Registration: and now it's 2004.... Dent Tech 2002; 55: 1–2.

LCS International Consulting Ltd. UK dental laboratory industry survey report 2001/2002. London: LCS International Consulting Ltd, 2002.

Dental technology - education and training issues. (Executive summary). Dent Lab 2003; 28: 4.

General Dental Council. Registering with the GDC. What it's all about - and what it will mean for you as professionals complementary to dentistry (PCDs). Available from http://www.gdc-uk-org/PCD_FAQs_Apr03.doc [accessed 2.5.03].

About statutory registration: part 2. Dent Tech 2003; 56: 1–2.

Dental educational resources on the web. Careers in dentistry - the dental technician. Available from http://www.derweb.co.uk [accessed 3.5.03].

LCS International Consulting Ltd. UK dental laboratory industry survey report 2002/2003. London: LCS International Consulting Ltd, 2003.

Murphy WM, Huggett R . Dental technician training in colleges and faculties of technology and further education in UK - a survey. Dent Tech 1984; 37: 5–10.

Barrett PA, Murphy WM . Dental technician education and training - a survey. Br Dent J 1999; 186: 85–88.

Poole C . 'To be or not to be?' The future of the process worker! Dent Lab 2003; 28: 6–7.

Challoner R . The changing roles of the dentist and dental laboratory. J Am Coll Dent 2002; 69: 6–8.

Ball A . 3.6% of bugger all is bugger all! Dent Lab 2002; 27: 1.

Leith R, Lowry L, O'Sullivan M . Communication between dentists and laboratory technicians. J Ir Dent Assoc 2000; 46: 5–10.

Davenport JC, Basker RM, Heath JR, Ralph JP, Glantz PO, Hammond P . Communication between the dentist and the dental technician. Br Dent J 2000; 189: 471–474.

Department of Health. Health and Social Care (Community Health and Standards) Bill. London: Department of Health, 2003.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Dental Technicians Association for its support and advice during the preparation of this survey, and would like to thank all those who took part in the survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bower, E., Newton, P., Gibbons, D. et al. A national survey of dental technicians: career development, professional status and job satisfaction. Br Dent J 197, 144–148 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811531

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811531

This article is cited by

-

Interrelationship between dental clinicians and laboratory technicians: a qualitative study

BMC Oral Health (2023)

-

Acceptance and experience of digital dental technology, burnout, job satisfaction, and turnover intention for Taiwanese dental technicians

BMC Oral Health (2022)

-

Current status of implant prosthetics in Japan: a survey among certified dental lab technicians

International Journal of Implant Dentistry (2015)

-

Communication methods and production techniques in fixed prosthesis fabrication: a UK based survey. Part 1: Communication methods

British Dental Journal (2014)

-

The impact of General Dental Council registration and continuing professional development on UK dental care professionals: (2) dental technicians

British Dental Journal (2012)