Key Points

-

The overall need for sedation appears to be around 5% of dental attenders.

-

Referral of those who usually do not need sedation may be appropriate for complex treatments or particular medical needs.

-

Medical history, patient reported anxiety and treatment complexity are important to consider when referring for sedation.

-

The IOSN system can be deployed by commissioners within populations to assess treatment need.

Abstract

Aim This service evaluation assessed the need for sedation in a population of dental attenders (n = 607) in the North West of England.

Methods Using the novel IOSN tool, three clinical domains of sedation need were assessed: treatment complexity, medical and behavioural indicators and patient reported anxiety using the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale.

Results The findings suggest that 5% of the population are likely to require a course of treatment under sedation at some time. All three clinical domains contributed to the IOSN score and indication of treatment need. Females were 3.8 times more likely than males to be placed within the high need for sedation group. Factors such as age, deprivation and practice location were not associated with the need for sedation.

Conclusions Primary care trusts (PCTs) need health needs assessment data in order to commission effectively and in line with World Class Commissioning guidelines. This study provides both an indicative figure of need as well as a tool by which individual PCTs can undertake local health needs assessment work. Caution should be taken with the figure as a total need within a population as the study has only included those patients that attended dental practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite advances in the delivery of dental treatment, fear and anxiety among patients are common findings.1,2,3 The prevalence of dental anxiety in populations has been reported in numerous studies and is summarised in Table 1.4 While it is accepted that these studies have used differing methodologies and scales (perhaps explaining the wide variation of prevalence), they demonstrate that, even with the conservative estimates of approximately 4%, this is a challenge for the dental community. Dental anxiety can be present in those who attend dental services but may also represent a significant barrier to those who do not access dentistry or who have a sporadic attendance for symptomatic treatment. It can be postulated that those individuals with significant anxiety will require some form of conscious sedation in order to receive treatment. For adults, this is most often intravenous sedation, typically using midazolam.5

In England, primary care trusts (PCTs) are currently the commissioning body for dental services for their local populations. In order to effectively commission services (of any kind) there is a requirement to understand the need for the service within the population and then the likely demand. A common example in dentistry is that of orthodontic services. Data from the child dental health services, combined with the use of a validated measurement of need (the IOTN scale) enable commissioners to accurately determine the level of orthodontic provision that is required.6,7,8,9 However, health needs assessment tools for other areas of dentistry are not well described and there is a need to develop and validate tools that enable PCTs to meet the best commissioning practice as described in World Class Commissioning.10,11

There are numerous drivers for examining the need for dental sedation within a population. Sedation can be an expensive treatment adjunct – and therefore it is essential that the correct amount of service is purchased to serve the needs of the population. However, without a sedation contract in place it can be argued that the commissioning body would be failing to meet the needs of those individuals whose dental anxiety prevents them seeking care and also that a quality dental service would offer sedation to those attending patients who needed it on a sporadic basis.12 Attending patients may need sedation frequently if they have high anxiety or they may be non-anxious patients who require complex treatment that is better delivered with sedation. For example, many regular attenders who receive their restorative care without any form of sedation may wish to receive it for a complex third molar extraction or bone graft surgery. Such an offer is a hallmark of a quality service – one where the personalised care of patients is considered and is responsive to their changing needs. The dental access targets across England remain within the NHS operating framework and hence PCTs are required to ensure that dental services are available to all those who want them. The offer of sedation to those with high anxiety could facilitate their attendance and hence assist in achieving equitable access.

Numerous methods for assessing dental sedation need have been used. Many of these are telephone-based surveys or questionnaires. This methodology is favoured as it reaches a representative sample of patients and prevents any bias associated with seeking data from those individuals who attend services. However, this approach concentrates on only one domain of treatment need – that of anxiety or fear.13,14,15,16 Recent work on the development of sedation needs assessment undertaken by the authors suggests that there are three domains to defining sedation need:

-

Treatment complexity

-

Medical and behavioural indicators

-

Patient anxiety.

By measuring only a single domain, for example anxiety, there is a risk that the need for sedation could be underestimated. Two examples would include the individual who is not anxious but whose medical condition indicates that they would, for certain procedures, receive care more effectively and/or safely with the benefit of conscious sedation. Second is the mildly anxious patient who regularly attends and receives care without the need for sedation but who requires a more complex procedure, for example an extraction involving bone removal. A simple questionnaire approach for this patient may fail to reveal the need for one-off or occasional sedation episodes for more complex or uncomfortable treatment.

The development of the Index of Sedation Need (IOSN) has been described in an earlier paper including details of the three domains, their assessment and their contribution to the overall IOSN metric score.17 The IOSN score is comprised of three metrics for each of the domains which contribute to the overall value. The scoring system is shown in Table 2.

It is important to note that the domains completed by the clinician are subjective and based on the referrer's assessment of the impact of the behaviour on the provision of treatment. For example, a gag reflex may be moderate but for that patient it may have a significant impact on the treatment time or complexity. The pragmatic nature of the index is accepted but is in common with many other medical and surgical complexity scales. The construct validity of this approach will be described in the fourth article in this series.

The purpose of the current study was to utilise the IOSN tool to determine sedation need among a population of attending patients and consider its utility as a health needs assessment tool.

Methods and materials

The study was conducted as a service evaluation of four practices in the North West of England. In order to obtain a spread of treatment complexities each practice was asked to complete a modified IOSN form for 100 Band 1, 2 and 3 patients. The NHS treatment banding system is shown in Figure 1. The IOSN form was modified to ensure that no personal data beyond sex, age and postcode was obtained. An ethical opinion was sought and it was determined that as no personally identifiable data would be collected, the study could be conducted without a formal ethical approval although all patients volunteered to complete the form and were not obliged to do so. The modified IOSN form is shown in Figure 2.

Patients and operators completed the forms which were then securely returned to the data entry team. Data were entered into SPSS, the IOSN score noted and, using postcode data, the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score obtained (the IMD scores are produced by combining data from seven domains: employment, health and disability, barriers to housing and services, living environment, crime, education skills, and training). Statistical analyses of the data utilised descriptives and comparisons between groups using Kruskal-Wallis and Mann Whitney U tests.

Results

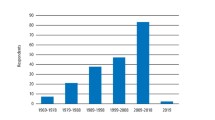

All four practices returned a total of 625 completed forms with 607 of them complete and included within the analysis. The distribution of treatment bands within the returned forms was Band 1 297 (49%), Band 2 209 (35%) and Band 3 100 (16%). The demographics of the respondents are shown in Table 3. The IMD scores for each practice are shown in Table 4 and analysis with Kruskal-Wallis followed by post-hoc Mann Whitney U tests demonstrated that there were significant differences in the IMD scores between all four practices.

Table 5 demonstrates the breakdown of IOSN scores across the 607 returned forms and provides a preliminary assessment that 1.8% have a high need for dental sedation. However, the IOSN protocol states that if any patient scores 4 on medical indicators then they are automatically placed into a high need category (if not already there) – there were three such patients in the sample and hence with these subjects included the overall needs assessment is 2.3%. Table 6 provides the breakdown of each of the three domains of the IOSN tool and their relative contribution to the overall IOSN score.

When assessing sedation need by sex, of those that had high need 91% were female and therefore were 6.7 times more likely to need to sedation compared to males in the sample. We examined predictive variables to determine if they had any effect on the need for sedation. Neither age (F (2,603) = 0.91, p >0.05), practice location (H (2) = 0.470, p >0.05) or deprivation score (H (2) = 5.318, p >0.05) had any significant effect. However the MDAS score (H (2) = 107.277, p <0.0001) and gender (χ² (2) = 13.43, p <0.05) were both statistically significant variables. Table 7 demonstrates these associations with only anxiety producing a significant difference in relation to sex or respondent. Females were 4.7 times more likely to be anxious in relation to dental treatment.

Table 6 demonstrates a potential flaw in the IOSN threshold and weighting systems. Anxiety is not distributed across the sedation need thresholds as one would expect. Within high sedation need there are five patients with high anxiety and five with moderate anxiety – however there are 34 patients present in the moderate need for sedation category that all scored high anxiety on the MDAS. Following assessment with a Mann Whitney U test there is a significant difference for anxiety between minimal and moderate need (U = 11653, z = −9.42, p <0.0001), and minimal and high need (U = 450, z = −4.77, p <0.0001). There is no significant difference between moderate and high need (U = 450, z = −4.77, p >0.05). From this we concluded that the anxiety score as it stands does not capture all of the patients that may require sedation due to their anxiety. The original weighting for the MDAS scores utilised three rankings, and treatment complexity and medical indicators had four. Table 8 demonstrates the new anxiety indicators that were devised in order to correct this anomaly, with Table 9 demonstrating the impact on sedation need distribution with a new needs indication of 5.1%. There was now a single respondent with a medical indicator score of 4 who was not in the high need group and hence, when added, takes the overall needs assessment for sedation to 5.3%. A Mann Whitney U test was applied to the revised figures and a significant difference between moderate and high sedation need was seen when considering anxiety score (U = 1725, z = −3.26, p <0.001).

Discussion

Despite the fact that a notable proportion of the population state they would prefer sedation during dental procedures, it is apparent that the preference or 'need' for sedation does not match the number of people who actually receive these services.4 It can be argued that with local commissioning there is a 'postcode lottery' of sedation provision which can lead to demand-led services in some areas and a failure to meet need in others. Due to the disparity between people's need for sedation and those that actually receive it, a sedation tool has been developed to assist PCTs in either estimating their sedation need by providing an indicative figure that can be modified, or by providing a tool which can be utilised should they wish to undertake their own health needs assessment.

Throughout the four dental practices involved in this study there were a higher proportion of female patients to male (overall 60:40). However this was not a statistically significant difference. This is an important fact as the only variable that showed a significant effect when looking at sedation need was gender, with females 6.7 times more likely to need sedation in relation to their dental treatment according to this sedation tool. Treatment complexity and medical score showed no significant association with gender. However, anxiety showed a significant relationship with gender with females 4.7 times more likely to be anxious in relation to their dental treatment. This corresponds with an earlier study where the authors reported females were 2.5 times more likely to report themselves as having a high level of dental fear.18 The fact that age, dental practice and deprivation showed no association with sedation need suggests that the results from this study can be generalised to populations from different locations and demographies and that the tool can be deployed in a range of settings. It should be noted that the mean age of participants (54 years old) was slightly higher than expected, however many previous studies have shown that a larger percentage of participants over the age of 35 say they have regular checkups compared to under-35s. In fact, a study in 199819 revealed that over-55s had the highest percentage of regular dental checkups, therefore this figure is not completely unexpected, although it may be sensible for future studies to use a greater variety of dental practices and a larger sample size in order to gain a more representative population.

The non-adjusted sedation tool showed that 2.4% of patients had a high need for sedation (Table 5). However, previous studies have shown the estimated need (or demand) is much higher. Chanpong, et al.18 reported 12.4% of respondents were definitely interested in sedation or GA for dental treatment. Dione's 1998 telephone survey stated that while 2.8% of people received sedation or GA, 8.6% would prefer it4 and a 2001 survey of Saudi adults found 9.8% preferred sedation for their dental treatment.20 However, many of these studies are actually reporting demand or preference rather than need.

Even though a number of the other studies involved telephone surveys and therefore may have captured a higher number of sedation respondents who do not even attend due to high anxiety (as they contacted both attendees and non-attendees), the figure reached in this study is so much lower it is safe to assume that the tool has not incorporated all of the 'high need for sedation' patients. In order to address this disparity the three components which made up the sedation score were examined. It can be seen in Table 7 that while treatment complexity and medical score showed a fairly expected distribution across sedation need (as sedation need rises so does the severity of these scores), anxiety showed a more unusual distribution with a high proportion of high anxiety patients in 'moderate sedation need' and an even spread of moderate to high anxiety patients in 'high sedation need'. This is reinforced when using Mann Whitney U as there was no significant difference between moderate and high need when looking at anxiety (but a significant difference for all other components and sedation need levels). It should also be noted that while treatment complexity and medical score had a range of 1-4, anxiety had a score which ranged from 1-3, giving a reduced weight to a variable that many would consider to be the more important metric within the tool. To re-address this problem the anxiety level was recalculated and split into four levels (see Table 8). This change meant the proportion of respondents that fell into high sedation rose from 2.4% to 5.1% and showed a significant difference when using Mann Whitney U between moderate and high sedation, when looking at anxiety. However a strong statistically significant male/female split continued, with females remaining 3.8 times more likely to be anxious in relation to their dental treatment.

It is interesting to note that out of the 607 respondents in this survey only three were referred for sedation services. All four practices in this area have access to sedation referral services and hence this finding needs to be considered against the backdrop of the needs assessment. This is a reflection that the IOSN tool presents a need for sedation at some point in time as many individuals will move between sedation need thresholds based on their treatment complexity scores.

Conclusion

This paper is the first in a series of three that consider the complex health needs assessment work surrounding dental sedation. At a simplistic level this work has suggested that 5% of patients will, at some time, need sedation services. Dental commissioners and others may choose to use this figure, adjust it to ensure that the rate of attendance, incidence of complex treatments and a need/demand conversion is considered and employ the resultant metric to check their sedation service need. Others may choose to undertake their own local health needs assessment using the tool.

The figures produced by this health needs assessment have some construct validity – they are inline with the internationally reported values and represent a richer assessment of need using the IOSN tool considering all three domains of clinical importance. However, caution should be drawn on the interpretation of the figures as they do not include non-attenders – indeed many believe that anxiety is a major barrier to accessing dentistry and therefore extremely phobic patients would not even attend an examination. This issue will be addressed in Paper 3, which takes into account non-attendees due to high levels of anxiety. A counter argument, however, is that services can only respond to those who access them – hence the requirement to convert any needs assessment to reflect likely demand (ie a PCT may have 20,000 smokers in need of smoking cessation, but only 2,000 may demand access to the service). Sedation is clearly a different need. The third paper in the series examines the issue of sedation need in non-attenders and the fourth will consider the use of the IOSN tool as a referral device and further validation of the health needs assessment.

References

Maggirias J, Locker D . Five-year incidence of dental anxiety in an adult population. Community Dent Health 2002; 19: 173–179.

McGrath C, Bedi R . The association between dental anxiety and oral health-related quality of life in Britain. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2004; 32: 67–72.

Meechan J G, Robb N D, Seymour R A . Pain and anxiety control for the conscious dental patient. Oxford: Oxford University press, 1998.

Dionne R A, Gordon S M, McCullagh L M, Phero J C . Assessing the need for anesthesia and sedation in the general population. J Am Dent Assoc 1998; 129: 167–173.

Corah N . Dental anxiety. Assessment, reduction and increasing patient satisfaction. Dent Clin North Am 1988; 32: 779–790.

Burden D J, Pine C M, Burnside G . Modified IOTN: an orthodontic treatment need index for use in oral health surveys. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2001; 29: 220–225.

Ucuncu N, Ertugay E . The use of the Index of Orthodontic Treatment need (IOTN) in a school population and referred population. J Orthod 2001; 28: 45–52.

Richmond S, Roberts C T, Andrews M . Use of the Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need (IOTN) in assessing the need for orthodontic treatment pre- and post-appliance therapy. Br J Orthod 1994; 21: 175–184.

Lunn H, Richmond S, Mitropoulos C . The use of the index of orthodontic treatment need (IOTN) as a public health tool: a pilot study. Community Dent Health 1993; 10: 111–121.

While A . World class commissioning. Br J Community Nurs 2008; 13: 494.

Ham C, Deffenbaugh J . On top of the world. World class commissioning. Health Serv J 2008; May 29: 22–24.

Kelly M, Steele J, Nuttall N et al. Adult dental health survey. Oral health in the United Kingdom 1998. London: Department of Health, 2000.

Kleinknecht R, Bernstein D . The assessment of dental fear. Behav Ther 1978; 9: 626–634.

Humphris G, Morrison T, Lindsay S J E . The Modified Dental Anxiety Scale: UK norms and evidence for validity. Community Dent Health 1995; 12: 143–150.

Humphris G M, Freeman R, Campbell J, Tuutti H, D'Souza V . Further evidence for the reliability and validity of the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale. Int Dent J 2000; 50: 367–370.

Corah N L . Development of a dental anxiety scale. J Dent Res 1969; 48: 596.

Coulthard P, Bridgman C M, Gough L, Longman L, Pretty I A, Jenner T . Estimating the need for dental sedation. 1. The Indicator of Sedation Need (IOSN) – a novel assessment tool. Br Dent J 2011; 211: E10.

Chanpong B, Haas D A, Locker D . Need and demand for sedation or general anesthesia in dentistry: a national survey of the Canadian population. Anesth Prog 2005; 52: 3–11.

Nuttall N M, Bradnock G, White D, Morris J, Nunn J . Dental attendance in 1998 and implications for the future. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 177–182.

Quteish Taani D S . Dental fear among a young adult Saudian population. Int Dent J 2001; 51: 62–66.

Acknowledgements

Dr Iain A Pretty is funded from a Clinician Scientist Award from the NIHR, and Mr Mohammed Sharif is funded from an In-Practice Fellowship Award from the NIHR. We are very grateful to the practices that took part and the Clinical Reference Group, Chaired by Dr Lesley Longman who provided helpful advice on the protocol for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pretty, I., Goodwin, M., Coulthard, P. et al. Estimating the need for dental sedation. 2. Using IOSN as a health needs assessment tool. Br Dent J 211, E11 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.726

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.726

This article is cited by

-

A review of the indicator of sedation need (IOSN): what is it and how can it be improved?

British Dental Journal (2018)

-

Conscious sedation: is this provision equitable? Analysis of sedation services provided within primary dental care in England, 2012–2014

BDJ Open (2016)

-

Utilising a paediatric version of the indicator of sedation need for children’s dental care: a pilot study

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (2016)

-

Assessing sedation need and managing referred dentally anxious patients: is there a role for the Index of Sedation Need?

British Dental Journal (2015)

-

Current UK dental sedation practice and the 'National Institute for Health and Care Excellence' (NICE) guideline 112: sedation in children and young people

British Dental Journal (2015)