Abstract

Drought has long been suspected as playing an important role in the abandonment of pre-Columbian Native American settlements across the midcontinental United States between 1350 and 1450 CE. However, high-resolution paleoclimatic reconstructions reflecting local effective moisture (the ratio of precipitation to evaporation) that are located in proximity to Mississippi period (1050–1450 CE) population centers are lacking. Here, we present a 1600-year-long decadally resolved oxygen isotope (δ18O) record from Horseshoe Lake (Collinsville, IL), an evaporatively influenced oxbow lake that is centrally located within the largest and mostly densely populated series of Mississippian settlements known as Greater Cahokia. A shift to higher δ18O in the Horseshoe Lake sediment record from 1200 to 1400 CE indicates that strongly evaporative conditions (i.e., low effective moisture) were persistent during the leadup to Cahokia’s abandonment. These results support the hypothesis that climate, and drought specifically, strongly impacted agriculturally based pre-Columbian Native American cultures in the midcontinental US and highlights the susceptibility of this region, presently a global food production center, to hydroclimate extremes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Between 1050 and 1450 CE, pre-Columbian (pre-1492 CE) Native American agriculturalists, collectively referred to as the Mississippians, developed and occupied an extensive network of settlements with large earthen mounds and plazas across the central Mississippi and lower Ohio River valleys1. The largest of these, Cahokia, was located near present-day Collinsville, IL (Fig. 1) and had an estimated peak population of 15,000–20,000 from 1100 to 1200 CE2,3. The Mississippians at Cahokia constructed plazas, causeways, fortifications, and hundreds of monumental earthen mounds, including Monks Mound4, which is the largest pre-Columbian North American earthwork north of Mexico5,6. Cahokia, and the associated St. Louis, East St. Louis and Mitchell precincts (i.e., Greater Cahokia), experienced rapid growth during this time, with locals and immigrants also populating the surrounding uplands to the east in a series of sites referred to as the Richland Complex7. After 1200 CE, social change and population decentralization occurred at Cahokia, as well as the surrounding regions8. This includes archaeological evidence for the construction of palisade walls around Cahokia’s central precinct9 and skeletal trauma patterns on human remains from the broader region indicating elevated levels of interpersonal violence and warfare9,10. Midcontinental population centers were ultimately abandoned by ca. 1450 CE, with only intermittent or small-scale occupations thereafter11,12.

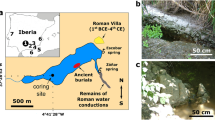

(A) Map of the American Bottom portion of the Mississippi River floodplain showing Horseshoe Lake’s position relative to prominent Mississippian urban centers (white circles), the largest of which was Cahokia (yellow dashed circle). Monks Mound, the largest earthwork at Cahokia, is indicated with a white square. The location from which the sediment core was collected is indicated with a red circle. (B) Hydrogen and oxygen isotope results for Indianapolis, IN, precipitation events (gray circles), Martin Lake, IN (green circles), Midwest lakes (light blue circles), and Horseshoe Lake (red circles). The white box indicates the intersection between the REL and RMWL that defines regional annual average δ18Oprecip. Average isotopic compositions of precipitation during past climate events, including the Medieval Climate Anomaly pluvial (orange square), Little Ice Age average and most severe drought from 1350 to 1450 CE (blue squares), and current warm period (red square) are also shown. δ18O values were calculated from δ18Ocal using an average temperature of 18 °C. Composite mean maps of (C) cold-season (December–March) and (D) warm-season (April–November) 850 hPa vector winds between 1949 and 2015 CE are from the NCEP-NCAR reanalysis database13. Arrows are wind directions with colored shading indicating velocity (m/s). Also plotted are mean back trajectories for cluster 1 (thick white line in A) and cluster 2 (thick red line in B) of the event-based Indianapolis, IN, precipitation samples. White squares are spaced at 24-h intervals. White circles indicate the starting point from which back trajectories were calculated. The mean back trajectories are in agreement with their respective seasonal atmospheric circulation patterns since 1949 CE. Paleoclimate records discussed in the text are shown with blue squares. Horseshoe Lake is indicated with a red square. Images provided by the NOAA/ESRL Physical Sciences Division, Boulder Colorado (http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/).

While the reasons behind the sudden growth and decline of the Mississippians are debated, climate change likely played a central role given that (1) Mississippian societies were dependent on agriculture and hence susceptible to warm-season drought, and (2) that the Vacant Quarter was formed during the Little Ice Age (LIA; ~ 1250–1830 CE), a time of known climatic volatility14,15,16,17. The role of climate is supported by recent findings that show an especially severe warm-season drought occurred across the midcontinental US between 1350 and 1450 CE as part of generally drier mean state conditions during the LIA13. While a climatic influence on the Mississippian period depopulation of the midcontinent is compelling, high-resolution paleoclimate evidence for drought conditions at major Mississippian population centers, like Greater Cahokia, is lacking.

Here, we test the climate hypothesis using a 1600-year-long authigenic calcite oxygen isotope record from Horseshoe Lake (δ18OHSL), an evaporatively modified oxbow lake situated just north of Cahokia and centrally located within the greater American Bottom region. Because of its sensitivity to evaporation, the δ18OHSL record reflects changes in the local balance between precipitation and evaporation (P/E). As such, the Horseshoe Lake record provides a means to assess the timing and nature of P/E balance changes (i.e., pluvial versus drought) that would have directly impacted the agricultural foundations of Cahokia and associated population centers, such as the St. Louis, East St. Louis, and Mitchell precincts18,19. The impact of climate change on Greater Cahokia’s occupation is further investigated by comparing the δ18OHSL record with published geochemical proxies of anthropogenic disturbances from Horseshoe Lake20. When interpreted with previously published proxy records, δ18OHSL reveals the temporal correspondence between regional P/E balance variability, Mississippian occupation, and land-use patterns.

Study site

Horseshoe Lake (38.6983°, − 90.0731°, 126 m asl) is a shallow (~ 5 m), oxbow lake (12 km2) with a ca. 200 km2 watershed located in the American Bottom portion of the Mississippi River floodplain just below the confluence with the Missouri River (Fig. 1). Although Horseshoe Lake is often flooded, its shallow depth and large surface area results in a hydrology that is sensitive to evaporation. This was reflected in field observations between the spring and summer of 2012 CE21, when drought caused lake levels to visibly fall and lake water δ18O values increased (Fig. 1B). Despite modifications to the lake’s watershed over the last 150 years, the lake’s residence time today is similar to the past because reductions in inflows as a result of stream diversions were offset by reductions in volume due to increased sedimentation (supplemental information). The modern responses to evaporation are therefore useful for considering how the lake would have responded to past droughts, including during the Mississippi Period. Authigenic calcite precipitated from the lake’s alkaline waters constitute an archive of variations in lake water δ18O that respond to changing effective moisture conditions that span the last 1600 years20.

Like much of the midcontinental US, climatic conditions in the American Bottom are characterized by strong seasonality. Winters are typically dominated by enhanced ridge and trough atmospheric circulation from November through March, which steers cold and dry 18O-depleted airmasses (δ18Oprecip = − 16.4‰) from the Pacific and Arctic into the region, resulting in precipitation and temperature minimums (Fig. 1)13,22. Warm-season conditions, conversely, are predominated by more zonal atmospheric circulation, which enhances clockwise atmospheric circulation over the eastern US and draws warm, moisture-laden air masses with less negative isotopic values (δ18Oprecip = − 5.5‰) from the Gulf of Mexico into the midcontinent (Fig. 1)13. As such, the warm season is characterized by temperature and precipitation maxima13. Changes in the frequency of air mass incursions from these two moisture sources, and hence the seasonal distribution and isotopic composition of precipitation, are strongly modulated by the Pacific North American (PNA) teleconnection, especially during the winter23,24,25. During negative (−) PNA phases, zonal atmospheric circulation is strengthened, increasing delivery of moisture from the Gulf of Mexico and resulting in high δ18Oprecip values. Positive (+) PNA phases are characterized by ridge (over the Rocky Mountains) and trough (over the midcontinental US) atmospheric circulation, increasing the frequency of northwesterly air mass incursions with low δ18Oprecip into the midcontinental US13,26. On decadal and longer timescales, PNA-like variability is modulated by the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), in which + PNA conditions are generally associated with + PDO conditions and vice versa27.

Results

Six surface water samples were analyzed from Horseshoe Lake and Mississippi River during March and August of 2012 CE. Surface water recovered from Horseshoe Lake in March were relatively depleted (δ18O = − 4.8‰, δ2H = − 34.7‰), reflecting reduced evaporation during the spring (Fig. 1B). During the severe drought conditions of August21, surface water levels visibly fell in Horseshoe Lake and δ18O values were enriched to + 1.0‰, an increase of 5.8‰ since March. The isotopic composition of surface water at Horseshoe Lake was more enriched than the isotopic composition of surface water recovered from the Mississippi River (δ18O = − 10.6‰, δ2H = − 84.8‰), demonstrating the lake’s sensitivity to evaporation.

Radiometric dates (i.e., 14C and 210Pb) indicate that Horseshoe Lake’s eastern basin contains calcite-rich sediment spanning at least the last 1600 years20, with each δ18OHSL measurement representing about 10 years on average (Fig. 2A). δ18OHSL values gradually decreased from ca. 400 to 1100 CE. Isotope values then abruptly decreased by 3.5‰ from 1100 to 1200 CE. From 1200 to 1450 CE, δ18OHSL increased by 3.7‰ and remained relatively stable from 1450 to 1800 CE. Starting around 1800 CE, δ18OHSL increased again reaching maximum values (− 4.2‰) in 1870 CE (Fig. 2A). After 1870 CE, δ18OHSL gradually declined until the end of the record in 2012 CE.

Proxy records for the last 1600 years. (A) Horseshoe Lake calcite δ18O data with 95% confidence intervals (this study). (B) Martin Lake calcite δ18O data13. (C) North Pacific Ocean sea surface temperature (SST) reconstruction. Negative SST anomalies indicate positive Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) conditions15. (D) Northern hemisphere temperature anomalies15 compared against the (E) pollen-based Midwest summer temperature reconstruction from Viau, et al.28.

Discussion

These δ18OHSL results are similar to a previously published low-resolution δ18O record from Horseshoe Lake that spanned the period from 940 to 1860 CE29, demonstrating that the δ18OHSL signal is robust. White et al.29, however, interpreted δ18OHSL as reflecting variations in summer versus winter precipitation, which neglects the significant influence of evaporative processes on the lake water (Fig. 1B), and hence δ18Ocal. A 5.8‰ increase in lake water δ18O and decline in water levels during the historic drought of 2012 CE21 suggests that modern Horseshoe Lake water is extremely sensitive to evaporation, and thus changes in P/E balance. Due to Horseshoe’s large surface area/volume ratio, both today and in the past, evaporation likely had a strong influence on lake water δ18O. The observed lake water isotopic enrichment in 2012 CE, for example, cannot be explained by changing precipitation sources or temperature alone because δ18O and δ2H values plot to the right of the regional meteoric water line on the regional evaporation line (Fig. 1B). This demonstrates that under reduced P/E, a substantial amount of water was removed from Horseshoe Lake via evaporation. Although the present watershed has been altered, water δ18O values were likely sensitive to evaporation in the past. For example, a major alteration of Horseshoe’s watershed occurred during the construction of the Cahokia Diversion Channel in the 1920s, which diverted a major portion of stream input away from the lake30. This change to watershed hydrology was offset by reductions in accommodation space as a result of sedimentation. As a result, Horseshoe Lake’s residence time remained effectively unchanged (supplemental information). This fact is illustrated by the minimal impact on the δ18OHSL record, which shows that the isotopic signal was not impacted by watershed modifications and is instead still mainly controlled by changes in P/E balance. In light of this evidence, we contend that evaporation would have been a significant influence on the isotopic composition of water at Horseshoe Lake in the past (as it is today), and hence δ18OHSL is a reliable indicator of past effective moisture (P/E) changes.

In addition to evaporation, the δ18O of authigenic calcite can also be affected by variations in temperature. However, estimated temperature changes of + / − 2 °C (see Fig. 2D, E) and historical drought temperatures31 are not large enough to explain the full 6.5‰ range in δ18O variability observed in the Horseshoe Lake sediment record. Taking into account the effects of temperature on δ18O includes a + 0.59‰ °C−1 influence on precipitation δ18O32 and − 0.22‰ °C−1 for calcite forming from lake water (i.e., δ18OHSL)33. The combined influences result in approximately 0.36‰ °C−1 in response to temperature changes. A 2 °C change during the LIA, for example, would then equate to a 0.72‰ change in δ18OHSL. For temperature to play a dominant role in δ18OHSL variability, past temperature variations would need to be on the order of 18 °C (6.5‰ δ18O range), which are unrealistically high (Fig. 2D, E).

Comparisons of δ18OHSL with the Martin Lake sediment calcite δ18O record (i.e., δ18OML) (41.56°, − 85.38°) suggest considerable changes in the predominance of different moisture sources to the midcontinent over the last 1600 years (Fig. 2B). Martin Lake, a small kettle lake in northeastern Indiana, has a short water residence time such that the δ18O of its surface waters reflects the isotopic composition of regional meteoric water (Fig. 1B)13. Although located approximately 500 km from Horseshoe Lake, the isotopic composition of precipitation at Martin and Horseshoe lakes are controlled by the same synoptic-scale atmospheric circulation processes13 and, as such, show consistent seasonal trends and similar annual average values that differ by less than 1‰ (Fig. S2). We therefore use the Martin Lake record to infer regional trends in the isotopic composition of precipitation as controlled by changes in atmospheric circulation during the last 1600 years. Accordingly, high δ18O at Martin Lake (δ18OML) indicates persistent − PNA-like atmospheric circulation that increased the advection of moisture from the Gulf of Mexico. Conversely, low δ18OML indicates + PNA-like atmospheric circulation patterns characterized by more frequent incursions of isotopically depleted airmasses from the northwest (Fig. 1C).

Lower δ18OHSL and higher δ18OML from 400 to 1200 CE indicate relatively high average P/E (i.e., wet conditions) during this time, whereas higher δ18OHSL and lower, but variable, δ18OML values from 1200 to 1870 CE indicate relatively drier (low P/E) conditions. Superimposed on these long-term trends was a period of particularly wet conditions (high P/E) at Cahokia indicated by δ18OHSL between 1000 and 1200 CE during the Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA; 950–1250 CE). The MCA was followed by decreasing P/E (drier conditions) at Cahokia, with δ18OHSL indicating an especially large reduction in P/E from 1200 to 1450 CE during the shift from the MCA to LIA (Fig. 2). During the MCA, high P/E corresponded with regional hydroclimate proxy evidence for higher water tables in Minnesota and Michigan34, reduced regional drought from the tree-ring Palmer Drought Severity Index35,36,37, warmer temperatures from a multi-site pollen-based summer temperature reconstruction28, and increased warm-season rainstorm events based on elevated lithic sediment delivery to Martin Lake13 (Fig. 3A). The opposite responses in the δ18OHSL and δ18OML data and other proxy records during the onset of the LIA indicate prolonged regional drought from 1350 to 1450 CE. These MCA and LIA hydroclimate anomalies were associated with synoptic-scale changes in ocean-atmospheric circulation, with moisture from the Gulf of Mexico predominating during the MCA warm-season wet phase in response to − PNA-like and − PDO-like conditions, and Pacific and Arctic moisture predominating during the LIA warm-season drought in response to + PNA-like and + PDO-like conditions13,15. The most severe reduction in P/E (i.e., drought) between 1350 and 1450 CE was associated with particularly strong + PDO and + PNA conditions that resulted in a shift to winter-dominated precipitation (75%) and severe reduction in warm-season rainfall13.

Proxy records from 800 to 1500 CE. (A) The Martin Lake % lithic record13. (B) Horseshoe Lake calcite δ18O data (this study). (C) Archaeological phases at Cahokia38 compared against (D) anthropogenic disturbance proxies20 and radiocarbon probability density functions for the (E) start and (F) end of palisade wall construction around Monks Mound9.

Comparison of previously published archaeological data from Greater Cahokia and the American Bottom with the δ18OHSL record suggests that mean state hydroclimate variations accompanied important cultural changes during the Mississippi period (1050–1450 CE)39,40. Previous research at Horseshoe Lake20 showed that lead (Pb) concentrations and total nitrogen isotopes (δ15N), interpreted as reflecting anthropogenic land-use disturbances, increased at Horseshoe Lake starting at ca. 1150 CE during the MCA when the δ18OHSL record indicates increased P/E (Fig. 3). After 1200 CE, when the first fortifications were built around Cahokia’s central precinct9, a steady increase in δ18OHSL indicates a reduction in P/E. The transition to drought conditions from ca. 1200 and 1400 CE correspond with a decline in Pb and δ15N at Horseshoe Lake (Fig. 3), as well as archaeological evidence for population decline and decentralization41,42, leading ultimately to the depopulation of Greater Cahokia6,16,20. The return of Pb and δ15N to background levels by 1350 CE is accompanied by a continued increase in δ18OHSL, suggesting the decline in human activity was associated with increasingly dry conditions at Horseshoe Lake (Fig. 3B, D).

The strong temporal correspondence between drought at Horseshoe and Martin lakes and the abandonment of Cahokia supports a causal relationship between regional climate and the decline of Greater Cahokia. One hypothesis is that increasing dependency on maize agriculture17 to support relatively high population densities (~ 21–27 persons km−2)43 and social complexity would have come with an increased susceptibility to climate change16. For example, empirical evidence has shown that maize yields are primarily determined by precipitation shortages during the growing season rather than excesses21. An extended period of dry conditions and low maize yields would have made it difficult to support the high population densities and level of social complexity that marked the growth and macro-regional influence of Cahokia between 1100 and 1200 CE2, when effective moisture and warm-season precipitation was high.

Conclusions

The δ18OHSL record indicates that Cahokia emerged as a regional center during the early Mississippi period (i.e., 1050–1200 CE) under relatively wet conditions with high effective moisture. These conditions likely contributed to the adoption of maize and development of a robust agricultural system that supported 15,000–20,000 individuals within and around Greater Cahokia between 1100 and 1200 CE. The onset of population declines within and around Cahokia ca. 1200 CE began as conditions trended toward lower effective moisture. Cahokia’s abandonment from 1350 to 1400 CE occurred during a prolonged regional drought, perhaps the most severe to strike the region in the last 1600 years. Paleoclimate records indicate that this drought was widespread in the midcontinental US and part of a general shift to more cold-season-like conditions during the LIA, with cooler, drier summers and colder, more severe winters in response to + PNA-like and + PDO-like conditions. These results support a strong link between climate anomalies and pre-Columbian demographic patterns in the American Bottom. Furthermore, these results indicate that the midcontinental US, presently a global agricultural center and home to more than 70 million people, is especially sensitive to severe and prolonged drought.

Methods

Sample collection, age modeling, δ18O, and δ2H analyses

Sediment cores and water samples were collected from Horseshoe Lake in 2012 and 2013 CE. The age-model and associated 95% confidence intervals for the interpolated ages were generated with CLAM (v. 2.2) using eight calibrated radiocarbon and 14 210Pb dates20. The δ18O of authigenic calcite isolated from the Horseshoe Lake sediment archive was measured using a Thermo Gas Bench II connected under continuous flow to a Thermo MAT 252 stable isotope ratio mass spectrometer at Indianapolis University–Purdue University in Indianapolis (IUPUI). All lake sediment calcite δ18O results are reported in standard delta notation relative to Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB) in ‰. Analytical precision, based on repeated measurements of standards, was 0.08 ‰ for calcite δ18O20. Regional surface water oxygen and hydrogen (δ2H) isotopes were analyzed at IUPUI using a Picarro L2130-i Analyzer44. Final values were corrected to Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW) and are in ‰. Analytical precision was 0.02‰ and 0.30‰ for water δ18O and δ2H, respectively.

Hydroclimate reconstructions

The oxygen isotopic composition of calcite precipitated from Horseshoe Lake’s water column reflects both variations in the isotopic composition of precipitation and the influence of local changes in the balance between precipitation and evaporation (P/E) variability on lake volume45. The oxygen isotopic composition of authigenic calcite can also be affected by variations in water temperature; however, estimated reconstructed temperature changes of +/− 2 °C are not large enough to explain the full range of δ18OHSL variability observed in the Horseshoe Lake sediment record (up to 6.5‰). A 2 °C change during the LIA, for example, would then equate to a 0.72‰ change in δ18O in Horseshoe Lake (see “Discussion” section). Variations in precipitation amount and moisture sources can have a larger impact on the isotopic composition of regional lake water δ18O13. Changes in the sources of δ18Oprecip therefore need to be accounted for in order to interpret the effects of P/E balance changes, and drought specifically, on δ18OHSL.

Regional δ18Oprecip was characterized using the Martin Lake, IN, sediment calcite δ18O record (δ18OML), which has been shown to reflect changes in moisture sources to the Midwest13 (Fig. 1). Average Martin Lake water δ18O plots at the intersection of the regional meteoric water line (RMWL) and the regional evaporation line (REL) along which Horseshoe Lake surface water evolves in response to evaporation (Fig. 1B). This indicates that Horseshoe Lake water evolved from an isotopic starting point indicated by Martin Lake δ2H–δ18O intercept along the RMWL. These isotopic relationships reflect the regional influence of synoptic-scale atmospheric circulation patterns that deliver precipitation from either northwesterly or southeasterly sources that have distinct δ18O signatures13,26. Back trajectory analysis of modern precipitation events together with climatological data spanning the last seven decades further demonstrates that moisture delivered to Martin Lake follows trajectories that pass over Horseshoe Lake (Fig. 1C, D). Therefore, comparisons of the δ18OHSL and δ18OML records are used to investigate changes in P/E balance at Horseshoe Lake and the broader Midwest.

References

Pauketat, T. R. Ancient Cahokia and the Mississippians (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Emerson, T. E. et al. Interrogating diaspora and movement in the greater Cahokian world. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 27, 54–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-019-09436-8 (2019).

Baires, S. E. Land of Water, City of the Dead, Religion and Cahokia’s Emergence 208 (University of Alabama Press, 2017).

Schilling, T. The chronology of Monks Mound. Southeast. Archaeol. 32, 14–28 (2013).

Blitz, J. H. & Livingood, P. Sociopolitical implications of Mississippian mound volume. Am. Antiq. 69, 291–301 (2004).

Emerson, T. E. & Hedman, K. M. The Dangers of Diversity: The consolidation and dissolution of Cahokia, native North America's first urban polity. In Beyond Collapse: Archaeological Perspectives on Resilience, Revitalization and Transformation in Complex Societies, vol. 42 (ed Ronald K. Faulseit) 147–175 (Southern Illinois University Press, 2016).

Pauketat, T. R. Resettled farmers and the making of a Mississippian polity. Am. Antiq. 68, 73–98 (2003).

Baltus, M. R. & Wilson, G. D. The Cahokian crucible: Burning ritual and the emergence of Cahokian power in the Mississippian midwest. Am. Antiq. 84, 438–470 (2019).

Krus, A. M. The timing of Precolumbian militarization in the US Midwest and Southeast. Am. Antiq. 81, 375–388 (2016).

Milner, G. R., Chaplin, G. & Zavodny, E. Conflict and societal change in late prehistoric Eastern North America. Evol. Anthropol. 22, 96–102 (2013).

Milner, G. R. & Chaplin, G. Eastern North American population at ca. A.D. 1500. Am. Antiq. 75, 707–726 (2010).

White, A. J., Munoz, S. E., Schroeder, S. & Stevens, L. R. After Cahokia: Indigenous repopulation and depopulation of the Horseshoe lake watershed AD 1400–1900. Am. Antiq. 85, 263–278. https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2019.103 (2020).

Bird, B. W., Wilson, J. J., Gilhooly, W. P. III., Steinman, B. A. & Stamps, L. Midcontinental Native American population dynamics and late Holocene hydroclimate extremes. Sci. Rep. 7, 41628. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep41628 (2017).

Kennett, D. J. & Marwan, N. Climatic volatility, agricultural uncertainty, and the formation, consolidation and breakdown of preindustrial agrarian states. Philos. Trans. Ser. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2014.0458 (2015).

Mann, M. E. et al. Global signatures and dynamical origins of the Little Ice Age and Medieval Climate Anomaly. Science 326, 1256–1260. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1177303 (2009).

Meeks, S. C. & Anderson, D. G. Drought, subsistence stress, and population dynamics: Assessing Mississippian abandonment of the Vacant Quarter. In Soils, Climate, & Society; Archaeological Investigations in Ancient America (eds Wingard, J. D. & Hayes, S. E.) 61-83 (University Press of Colorado, 2013).

Emerson, T. E., Hedman, K. M., Simon, M. L., Fort, M. A. & Witt, K. E. Isotopic confirmation of the timing and intensity of maize consumption in Greater Cahokia. Am. Antiq. 85, 241–262. https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2020.7 (2020).

Emerson, T. E., Koldehoff, B. & Brennan, T. K. Revealing Greater Cahokia, North America's first native city: Rediscovery and large-scale excavations of the East St. Louis Precinct. In ISAS Studies in Archaeology No. 12 (Illinois State Archaeological Survey, 2018).

Pauketat, T. R., Emerson, T. E., Farkas, M. G. & Baires, S. E. An American Indian City. In Medieval Mississippians: The Cahokian World (eds Pauketat, T. R. & Alt, S. M.) (School for Advanced Research Press, 2015).

Pompeani, D. P. et al. The environmental impact of a pre-Columbian city based on geochemical insights from lake sediment cores recovered near Cahokia. Quat. Res. 91, 714–728. https://doi.org/10.1017/qua.2018.141 (2019).

Rippey, B. R. The U.S. drought of 2012. Weather Clim. Extremes 10, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2015.10.004 (2015).

Andresen, J. S., Hilberg, K. & Kunkel, K. Historical Climate and Climate Trends in the Midwestern USA 1–18 (Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessents, 2012).

Leathers, D. J., Yarnal, B. & Palecki, M. A. The Pacific/North American teleconnection pattern and United States Climate. Part I: Regional temperatures and precipitation associations. J. Clim. 4, 517–528 (1991).

Liu, Z., Yoshmura, K., Bowen, G. J. & Welker, J. M. Pacific-North American teleconnection controls on precipitation isotopes (δ18O) across the Contiguous United States and adjacent regions: A GCM-based analysis. J. Clim. 27, 1046–1061. https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-13-00334.1 (2014).

Coleman, J. S. M. & Rogers, J. C. Ohio River valley winter moisture conditions associated with the Pacific-North American teleconnection pattern. J. Clim. 16, 969–981 (2003).

Tian, C., Wang, L., Kaseke, K. F. & Bird, B. W. Stable isotope compositions (delta(2)H, delta(18)O and delta(17)O) of rainfall and snowfall in the central United States. Sci. Rep. 8, 6712. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25102-7 (2018).

Yu, B. & Zwiers, F. W. The impact of combined ENSO and PDO on the PNA climate: A 1,000-year climate modeling study. Clim. Dyn. 29, 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-007-0267-4 (2007).

Viau, A. E., Gajewski, K., Sawada, M. C. & Fines, P. Millennial-scale temperature variations in North America during the Holocene. J. Geophys. Res. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005jd006031 (2006).

White, A. J. et al. Fecal stanols show simultaneous flooding and seasonal precipitation change correlate with Cahokia’s population decline. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116, 5461–5466. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1809400116 (2019).

Rankin, C. G. Testing Assumptions on the Relationship Between Humans and Their Environment: Case Studies from Cahokia Mounds, Illinois. (Washington University, St. Louis, 2020).

Muñoz, S. E. et al. Lipid biomarker record documents hydroclimatic variability of the Mississippi River basin during the common era. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020gl087237 (2020).

Rozanski, K., Araguás-Araguás, L. & Gonfiantini, R. Relation between long-term trends of oxygen-18 isotope composition of precipitation and climate. Science 258, 981–985 (1992).

Kim, S. T. & O’Neil, J. R. Equilibrium and nonequilibrium oxygen isotope effects in synthetic carbonates. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 61, 3461–3475 (1997).

Booth, R. K., Notaro, M., Jackson, S. T. & Kuzbach, J. E. Widespread drought episodes in the western Great Lakes region during the past 2000 years: Geographic extent and potential mechanisms. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 242, 415–427 (2006).

Benson, L. V., Pauketat, T. R. & Cook, E. R. Reply to comments of Nolan and Cook. Am. Antiq. 75, 984–985. https://doi.org/10.7183/0002-7316.75.4.984 (2017).

Benson, L., Pauketat, T. R. & Cook, E. Cahokia’s boom and bust in the context of climate change. Am. Antiq. 74, 467–483 (2009).

Nolan, K. C. & Cook, R. A. Volatile climate conditions Cahokia: Comment on Benson, Pauketat and Cook 2009. Am. Antiq. 75, 978–983. https://doi.org/10.7183/0002-7316.75.4.978 (2017).

Fortier, A., Emerson, T. E. & McElrath, D. Calibrating and reassessing American bottom culture history. Southeast. Archaeol. 25, 170–211 (2006).

Baires, S. E., Baltus, M. R. & Malouchos, E. W. Exploring New Cahokian neighborhoods: Structure density estimates from the Spring Lake Tract, Cahokia. Am. Antiq. 82, 742–760. https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2017.33 (2017).

Comstock, A. R. & Cook, R. A. Climate change and migration along a Mississippian periphery: A Fort Ancient example. Am. Antiq. 83, 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2017.50 (2017).

White, A. J. et al. An evaluation of fecal stanols as indicators of population change at Cahokia, Illinois. J. Archaeol. Sci. 93, 129–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2018.03.009 (2018).

Milner, G. R. Mississippian period population density in a segment of the central Mississippi River Valley. Am. Antiq. 51, 227–238 (1986).

Milner, G. R. The Cahokia Chiefdom: The archeology of a Mississippian society. (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998).

van Geldern, R. & Barth, J. A. Optimization of instrument setup and post-run corrections for oxygen and hydrogen stable isotope measurements of water by isotope ratio infrared spectroscopy (IRIS). Limnol. Oceanogr. 10, 1024–1036 (2012).

Leng, M. & Marshall, J. D. Palaeoclimate interpretation of stable isotope data from lake sediment archives. Quat. Sci. Rev. 23, 811–831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2003.06.012 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We thank Robert McDermont, Justin Coughlin, Christopher Purcell, and Katherine Pompeani for their help in the field. This work was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship in the Department of Geology at Kansas State University. Support for this research was also provided by award EAR-1903628 from the National Science Foundation. Isotope data are archived online at the NOAA Paleoclimatology Database.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.P.P.: conceptualization, writing, laboratory work, fieldwork. B.W.B.: water isotope analysis, writing, editing, Fig. 1. J.J.W.: writing, editing, literature review. W.P.G.: calcite oxygen isotope analysis. A.L.H.: writing, editing, fieldwork. M.S.F.: radiocarbon dating, editing, fieldwork. M.B.A.: editing, laboratory and fieldwork support. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pompeani, D.P., Bird, B.W., Wilson, J.J. et al. Severe Little Ice Age drought in the midcontinental United States during the Mississippian abandonment of Cahokia. Sci Rep 11, 13829 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92900-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92900-x

This article is cited by

-

European tree-ring isotopes indicate unusual recent hydroclimate

Communications Earth & Environment (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.