Abstract

No study has examined the associations between vitiligo and smoking. The purpose of this study was to investigate the incidence of vitiligo according to smoking status. We used clinical data from individuals aged over 20 years who received a health examination in the National Insurance Program between 2009 and 2012 (n = 23,503,807). We excluded individuals with pre-existing vitiligo who had ever been diagnosed with vitiligo before the index year (n = 35,710) or who were diagnosed with vitiligo within a year of the index year (n = 46,476). Newly diagnosed vitiligo was identified using claims data from baseline to date of diagnosis or December 31, 2016 (n = 22,811). The development of vitiligo was compared according to self-reported smoking status by a health examination survey. The hazard ratio of vitiligo in current smokers was 0.69 (95% confidence interval; 0.65–0.72) with a reference of never-smokers after adjustment for age, sex, regular exercise, drinking status, body mass index, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, history of stroke, and history of ischemic heart diseases. The decreased risk of vitiligo in current smokers persisted after subgroup analysis of sex and age groups. The results suggested there are suppressive effects of smoking on the development of vitiligo. Further studies are needed to evaluate the mechanism of smoking on the development of vitiligo.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vitiligo is a common depigmentation skin disease with an estimated prevalence of 0.5–1% in the worldwide population1. Vitiligo affects all skin types and ethnic groups. The highest incidence is recorded in India (up to 8.8%)2, followed by Mexico (4%)3, Japan (1.68%)4, and Denmark (0.38%)5. The annual incidence of vitiligo in South Korea was estimated at 0.12–0.13%6.

Vitiligo is a multifactorial disease. It is hypothesized to be mainly caused by autoimmune factors, although genetic susceptibility, oxidative stress, and cell detachment abnormalities are also suggested etiologies7. The autoimmune diseases vitiligo is associated with include autoimmune thyroid disorders, rheumatoid arthritis, adult-onset diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, and systemic lupus erythematosus8,9.

Once vitiligo develops, it is difficult to treat and affects quality of life. Vitiligo can negatively affect social relations10,11,12,13. One study showed that vitiligo has an adverse effect on patient sexuality14, and it has been associated with pessimistic emotions such as shame, insecurity, and sadness15. Therefore, evaluating the preventive and risk factors for vitiligo is important.

Smoking is one of the most prevalent addictive habits that affects multi-organ systems and results in several diseases. The well-known risks of smoking habits include respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. Smoking also affects the immune system and results in inflammatory reactions. Tobacco contains as many as 6,000 different components including nicotine, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, tobacco glycoprotein, and some metals, many of which are considered antigenic, cytotoxic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic. The effects of smoking are considered to be harmful for human health. In terms of autoimmune skin diseases, the results have been conflicting according to various skin diseases. Smoking is known to have detrimental effects on and a positive association with psoriasis16,17,18,19, palmoplantar pustulosis,20 and hidradenitis suppurativa21,22,23,24,25,26,27. However, several autoimmune skin diseases, such as pemphigus vulgaris, foliaceous, and28,29,30,31,32,33 Behçet’s disease34,35,36, show a negative association with smoking. We recently reported that the incidence of Behçet’s disease in current smokers was significantly decreased compared to that of never-smokers in South Korea36. Until now, the association between vitiligo and smoking has not been evaluated or reported.

Herein, this study aimed to investigate the incidence of vitiligo according to smoking habits using a nationwide population-based cohort design to analyze data from the National Health Insurance Research Database in Korea.

Materials and Methods

Study design and database

This study used the same dataset that was previously reported;36 the Korean Health Examination database and the Korean National Health Insurance Service (KNHIS) claims database. Briefly, the KNHIS database contains all claims data for the KNHIS program, the Korean Medical Aid program, and all other long-term care insurance programs for 99% of the Korean population and the Korean National Health Examination database was used to select participants and obtain information on confounding variables. The health examination data included anthropometric measures, smoking status, drinking, and exercise, and self-reported medical histories. Per the methods in the previous paper36, we used the linked KNHIS claims database for the same individuals to evaluate the development of vitiligo.

This nationwide, population-based retrospective cohort study used the KNHIS Claims Database (diagnoses according to the International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] code). The Institutional Review Board at the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention approved the protocol (NHIS-2018-1-333). The study was also approved by the Institutional Review Board at Uijeongbu St. Mary’s Hospital, Catholic University of Korea and was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Anonymized and de-identified information were used for analyses, and therefore informed consent was not required.

Study population

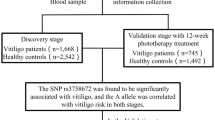

The total number of individuals who underwent National Health Examinations in Korea from 2009 until 2012 was 23,503,802. The first year an individual received a health examination was considered the index year. We excluded individuals aged less than 20 years (n = 50,940) or who had missing data in the health examination survey (n = 379,035). To identify newly diagnosed vitiligo, we excluded individuals with pre-existing vitiligo who had ever been diagnosed with vitiligo before the index year (n = 35,710) or who were diagnosed with vitiligo within a year of the index year (n = 46,476). The observation began a year after the date of the baseline Health Examination in all subjects and ended when vitiligo was diagnosed or December 31, 2016. (Fig. 1)

Subgroups according to smoking status

Smoking status was obtained from a self-reported questionnaire during the health examination. Study individuals (n = 22,991,641) were divided into three groups according to smoking status; never-smoker (n = 14,345,458), ex-smoker (n = 3,042,684), and current smoker (n = 5,603,499). (Fig. 1) The amount of smoking was sub-grouped into <10 cigarettes per day, 10–19 cigarettes per day, and ≥20 cigarettes per day, and smoking duration was divided into <10 years, 10–29 years, and ≥30 years.

Comorbidities

To adjust for comorbidities, the presence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia were defined using ICD-10 codes: diabetes mellitus (E11-14), hypertension (I10-13 and I15), and dyslipidemia (E78) with medication in KNHIS database. History of stoke or ischemic heart disease was obtained by self-reported questionnaire during the National Health examination.

Statistical analysis

We considered comorbidities including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, ischemic heart disease, and stroke as possible confounders to adjust in our analyses. Cox’s proportional hazard regression models with an age timescale were used to identify the associations between smoking status and newly diagnosed vitiligo. Hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for smoking status were compared to the reference (never-smoker). We performed the subgroup analyses separately for men and women and age groups (20–39 years, 40–65 years, ≥65 years). Proportional hazard assumptions were checked using log-log cumulative survival graphs and the time-dependent variable Cox model after adjustment for baseline covariates including age, sex, regular exercise, drinking status, BMI, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, history of stroke, and history of myocardial infarction, according to smoking status. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (ver. 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Characteristics of the study population

Among the 22,991,641 individuals, 14,345,458 were never-smokers, 3,042,684 were ex-smokers, and 5,603,499 were current smokers. The current smokers (43.34 ± 12.87 years) were younger than never-smokers (48.86 ± 14.8 years) and ex-smokers (50.11 ± 13.4 years). The percentage of men was significantly higher in ex-smokers and current smokers than in never-smokers. Drinking habits (2–3 times a month) were higher in ex-smokers and current smokers. Comorbidities including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia were highest in ex-smokers. History of previous stroke and ischemic heart disease was also higher in ex-smokers. (Table 1).

Newly diagnosed vitiligo according to smoking status

There were 16,515 newly diagnosed cases of vitiligo in never-smokers, 3,003 cases in ex-smokers, and 3,293 cases in current smokers. The incidence of newly diagnosed vitiligo was 2.63 per 10,000 person-years in never-smokers, 2.23 per 10,000 person-years in ex-smokers, and 1.35 per 10,000 person-years in current smokers. The cumulative incidence of newly diagnosed vitiligo after adjustment for covariates is shown in Fig. 2 according to smoking status. Current smokers had a significantly lower risk of vitiligo (HR 0.51, 95% CI, 0.50–0.53) compared with never-smokers. Decreased risk of newly diagnosed vitiligo in current smokers persisted after setting an age timescale in Model 1 (HR 0.56, 95% CI, 0.54–0.59) and adjustment for covariates in Model 2 (HR 0.68, 95% CI, 0.64–0.71) and Model 3 (HR 0.69, 95% CI, 0.65–0.72). Sensitivity analysis also showed decreased vitiligo risk in current smokers regardless of age or sex (Table 2).

Subgroup analysis of amount and duration of smoking

Current smokers showed a decrease in HR for newly diagnosed vitiligo in proportion to the amount of smoking compared with never-smokers; HR 0.70, 95% CI, 0.64–0.76) in current smokers who smoked less than 10 cigarettes a day, HR 0.51, 95% CI, 0.49–0.52 in current smoker who smoked 10–29 cigarettes a day, and HR 0.47, 95% CI, 0.44–0.49 in current smoker who smoked more than 30 cigarettes a day. (Table 3) Current smokers showed decreased HR for vitiligo regardless of smoking duration compared with never-smokers.

Discussion

We report a negative association between tobacco smoking and newly diagnosed vitiligo using a nation-wide cohort database. No study has reported on the incidence of vitiligo associated with smoking status.

The detrimental effects of smoking have been reported for several skin diseases. Palmoplantar pustulosis is well known to be prevalent in current or ex-smokers20. Psoriasis is related to smoking habits and heavier smoking is reported to increase the relative risk of psoriasis and its severity16,17,18,19. Smoking is also considered a triggering factor in hidradenitis suppurativa21,22,23,24,25,26,27 and systemic lupus erythematosus37,38,39. Smoking has detrimental effects on wound healing40 and skin aging41,42,43.

In contrast, protective effects of smoking have also been reported for several skin diseases. Case-control studies report that pemphigus vulgaris and foliaceous occur less frequently in current and ex-smokers28,29,30,31,32,33. Development of aphthous ulcers is associated with cessation of smoking44,45,46,47,48,49,50. The beneficial effects of smoking on oral ulcers in Behçet’s disease has been shown in several reports34,35,36. Behçet’s disease oral lesions appear after cessation of smoking; therefore, the beneficial effects of nicotine have been suggested51,52,53,54. However, some studies report that smoking is not a significant risk factor for Behçet’s disease55, and smoking is a risk factor for vasculitis and neurological manifestations of the disease56,57. (Table 4) In addition to skin diseases, Parkinson’s disease58,59,60 is inversely associated with smoking without exact known mechanisms. Ulcerative colitis is well-known to be inversely associated with smoking61. Until now, the association between vitiligo and smoking has not been evaluated or reported.

The pro-oxidant and anti-oxidant effects of smoking are suggested in several studies. Tobacco contains a variety of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Therefore, smoking has deleterious effects on human health. Otherwise, tobacco also contains compounds that inhibit the activity of monoamine oxidase (MAO) and can reduce the level of ROS produced by MAO. There has been a report that smokers have lower MAO activity than never-smokers62,63. Another study reported that nicotine chelates ferrous ions that produce oxygen radicals and functions as an antioxidant64.

In this study, the risk of vitiligo decreased in current smokers in relation to smoking dose. This result was counter to our expectation that the oxidative stress incurred from smoking would cause vitiligo development. Vitiligo is an acquired depigmentation skin disease caused by destruction of melanocytes in affected skin. Oxidative stress and autoimmunity are important in pathogenic events in melanocyte loss65. Increased levels of ROS, mainly H2O2, are reported in the epidermis of vitiligo skin66. Elevated NADPH oxidase activity and increased production of ROS and reactive nitrogen species are reported in vitiligo patients67. Increased activity of MAO is reported in vitiligo epidermis that results in accumulation of H2O268. Low levels of antioxidants, such as catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and superoxide dismutase are reported in the epidermis and serum of vitiligo patients69,70. The inverse relationship between vitiligo and smoking might be explained by inhibitory effects on MAO due to tobacco smoking62. However, the exact mechanism needs to be evaluated by further studies.

Considering the harm caused by smoking and the lack of a distinct benefit for vitiligo development, we do not think smoking should be considered as a prevention or treatment option for vitiligo. We suggest investigating the mechanism of smoking in vitiligo development in vitro and in vivo in further studies. We present a new topic in vitiligo research in a field with little progress and limited development of treatment options.

There are several limitations in our study. First, the genetic susceptibility of individuals or family history of vitiligo was not evaluated. Second, causal links between smoking and vitiligo could not be identified in an epidemiologic study. Third, the status of smoking was obtained from self-reported questionnaires during the health examination and a response bias caused by respondents failing to provide correct information cannot be ruled out. And the absence of data on time since quitting smoking in ex-smokers is considered as a limitation in this study. The role of smoking in vitiligo development remains for additional clinical analysis or in vitro studies.

Several strengths in this study are that first, we examined the relationship between vitiligo and smoking in the South Korean population. This study used a nation-wide population-based cohort. In Korea, a general health examination, either biannually or annually according to occupation, is mandatory for local household owners, office employees, and family members over the age of 40 years. The total number of individuals who underwent National Health Examinations in Korea from 2009 until 2012 was 23,503,802 that was more than half of the total population of Korea. Considering that we excluded subjects less than 20 years old, the results of this study could generalize the majority of Koreans who receive a medical examination. We identified the possible suppressive effects of smoking on the development of vitiligo. Current smokers showed a decreased risk of vitiligo development compared to non-smokers regardless of age and sex, and the amount of smoking was negatively correlated with vitiligo development. The suppressive mechanism of smoking on the cutaneous autoimmune disease, vitiligo, is unknown. Further in vitro studies are needed to investigate the exact mechanism between smoking and vitiligo. However, this study helps to broaden the understanding of vitiligo pathogenesis.

References

Ezzedine, K., Eleftheriadou, V., Whitton, M. & van Geel, N. Vitiligo. Lancet 386, 74–84, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60763-7 (2015).

Behl, P. N. & Bhatia, R. K. 400 cases of vitiligo. A clinico-therapeutic analysis. Indian journal of dermatology 17, 51–56 (1972).

Canizares, O. Geographic dermatology: Mexico and Central America. The influence of geographic factors on skin diseases. Arch Dermatol 82, 870–893 (1960).

Furue, M. et al. Prevalence of dermatological disorders in Japan: a nationwide, cross-sectional, seasonal, multicenter, hospital-based study. The Journal of dermatology 38, 310–320, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01209.x (2011).

Howitz, J., Brodthagen, H., Schwartz, M. & Thomsen, K. Prevalence of vitiligo. Epidemiological survey on the Isle of Bornholm, Denmark. Arch Dermatol 113, 47–52 (1977).

Lee, H. et al. Prevalence of vitiligo and associated comorbidities in Korea. Yonsei medical journal 56, 719–725, https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2015.56.3.719 (2015).

Picardo, M. et al. Vitiligo. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 15011, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2015.11 (2015).

Liu, J. B. et al. Clinical profiles of vitiligo in China: an analysis of 3742 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol 30, 327–331, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2230.2005.01813.x (2005).

Chen, Y. T. et al. Comorbidity profiles in association with vitiligo: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology: JEADV 29, 1362–1369, https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.12870 (2015).

Eleftheriadou, V. Living with vitiligo: development of a new vitiligo burden questionnaire is a step forward for outcomes consensus. Br J Dermatol 173, 331–332, https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.13984 (2015).

Ezzedine, K. et al. Living with vitiligo: results from a national survey indicate differences between skin phototypes. Br J Dermatol 173, 607–609, https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.13839 (2015).

Ezzedine, K. et al. Vitiligo is not a cosmetic disease. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 73, 883–885, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.039 (2015).

Salzes, C. et al. The Vitiligo Impact Patient Scale (VIPs): Development and Validation of a Vitiligo Burden Assessment Tool. The Journal of investigative dermatology, https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2015.398 (2015).

Sukan, M. & Maner, F. The problems in sexual functions of vitiligo and chronic urticaria patients. Journal of sex & marital therapy 33, 55–64, https://doi.org/10.1080/00926230600998482 (2007).

Nogueira, L. S., Zancanaro, P. C. & Azambuja, R. D. [Vitiligo and emotions]. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia 84, 41–45 (2009).

Mills, C. M. et al. Smoking habits in psoriasis: a case control study. Br J Dermatol 127, 18–21 (1992).

Emre, S. et al. The relationship between oxidative stress, smoking and the clinical severity of psoriasis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology: JEADV 27, e370–375, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04700.x (2013).

Attwa, E. & Swelam, E. Relationship between smoking-induced oxidative stress and the clinical severity of psoriasis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology: JEADV 25, 782–787, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03860.x (2011).

Fortes, C. et al. Relationship between smoking and the clinical severity of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol 141, 1580–1584, https://doi.org/10.1001/archderm.141.12.1580 (2005).

Eriksson, M. O., Hagforsen, E., Lundin, I. P. & Michaelsson, G. Palmoplantar pustulosis: a clinical and immunohistological study. Br J Dermatol 138, 390–398 (1998).

Akdogan, N. et al. Visfatin and insulin levels and cigarette smoking are independent risk factors for hidradenitis suppurativa: a case-control study. Arch Dermatol Res 310, 785–793, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-018-1867-z (2018).

Micheletti, R. Tobacco smoking and hidradenitis suppurativa: associated disease and an important modifiable risk factor. Br J Dermatol 178, 587–588, https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.16261 (2018).

Melnik, B. C., John, S. M., Chen, W. & Plewig, G. T helper 17 cell/regulatory T-cell imbalance in hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: the link to hair follicle dissection, obesity, smoking and autoimmune comorbidities. Br J Dermatol 179, 260–272, https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.16561 (2018).

Dessinioti, C. et al. A retrospective institutional study of the association of smoking with the severity of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Dermatol Sci 87, 206–207, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdermsci.2017.04.006 (2017).

Denny, G. & Anadkat, M. J. The effect of smoking and age on the response to first-line therapy of hidradenitis suppurativa: An institutional retrospective cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 76, 54–59, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.041 (2017).

Simonart, T. Hidradenitis suppurativa and smoking. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 62, 149–150, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.001 (2010).

Konig, A., Lehmann, C., Rompel, R. & Happle, R. Cigarette smoking as a triggering factor of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology 198, 261–264, https://doi.org/10.1159/000018126 (1999).

Kridin, K., Zamir, H. & Cohen, A. D. Cigarette smoking associates inversely with a cluster of two autoimmune diseases: ulcerative colitis and pemphigus. Immunol Res 66, 555–556, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12026-018-9021-8 (2018).

Lai, O., Recke, A., Zillikens, D. & Kasperkiewicz, M. Influence of cigarette smoking on pemphigus - a systematic review and pooled analysis of the literature. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology: JEADV, https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14886 (2018).

Valikhani, M. et al. Impact of smoking on pemphigus. Int J Dermatol 47, 567–570, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03645.x (2008).

Sullivan, T. P., Elgart, G. W. & Kirsner, R. S. Pemphigus and smoking. Int J Dermatol 41, 528–530 (2002).

Valikhani, M. et al. Pemphigus and associated environmental factors: a case-control study. Clin Exp Dermatol 32, 256–260, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02390.x (2007).

Brenner, S. et al. Pemphigus vulgaris: environmental factors. Occupational, behavioral, medical, and qualitative food frequency questionnaire. Int J Dermatol 40, 562–569 (2001).

Kaklamani, V. G., Tzonou, A., Markomichelakis, N., Papazoglou, S. & Kaklamanis, P. G. The effect of smoking on the clinical features of Adamantiades-Behcet’s disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 528, 323–327, https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-48382-3_64 (2003).

Soy, M., Erken, E., Konca, K. & Ozbek, S. Smoking and Behcet’s disease. Clin Rheumatol 19, 508–509, https://doi.org/10.1007/s100670070020 (2000).

Lee, Y. B. et al. Association between smoking and Behcet’s disease: a nationwide population-based study in Korea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 33, 2114–2122, https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.15708 (2019).

Costenbader, K. H. & Karlson, E. W. Cigarette smoking and systemic lupus erythematosus: a smoking gun? Autoimmunity 38, 541–547, https://doi.org/10.1080/08916930500285758 (2005).

Costenbader, K. H. et al. Cigarette smoking and the risk of systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum 50, 849–857, https://doi.org/10.1002/art.20049 (2004).

Kiyohara, C. et al. Cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and risk of systemic lupus erythematosus: a case-control study in a Japanese population. J Rheumatol 39, 1363–1370, https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.111609 (2012).

Kean, J. The effects of smoking on the wound healing process. J Wound Care 19, 5–8, https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2010.19.1.46092 (2010).

Helfrich, Y. R. et al. Effect of smoking on aging of photoprotected skin: evidence gathered using a new photonumeric scale. Arch Dermatol 143, 397–402, https://doi.org/10.1001/archderm.143.3.397 (2007).

Kennedy, C. et al. Effect of smoking and sun on the aging skin. The Journal of investigative dermatology 120, 548–554, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12092.x (2003).

Yin, L., Morita, A. & Tsuji, T. Skin premature aging induced by tobacco smoking: the objective evidence of skin replica analysis. J Dermatol Sci 27(Suppl 1), S26–31 (2001).

Subramanyam, R. V. Occurrence of recurrent aphthous stomatitis only on lining mucosa and its relationship to smoking–a possible hypothesis. Med Hypotheses 77, 185–187, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2011.04.006 (2011).

Sawair, F. A. Does smoking really protect from recurrent aphthous stomatitis? Ther Clin Risk Manag 6, 573–577, https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S15145 (2010).

Marakoglu, K., Sezer, R. E., Toker, H. C. & Marakoglu, I. The recurrent aphthous stomatitis frequency in the smoking cessation people. Clin Oral Investig 11, 149–153, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-007-0102-7 (2007).

Atkin, P. A., Xu, X. & Thornhill, M. H. Minor recurrent aphthous stomatitis and smoking: an epidemiological study measuring plasma cotinine. Oral Dis 8, 173–176 (2002).

Tuzun, B., Wolf, R., Tuzun, Y. & Serdaroglu, S. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis and smoking. Int J Dermatol 39, 358–360 (2000).

Shapiro, S., Olson, D. L. & Chellemi, S. J. The association between smoking and aphthous ulcers. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 30, 624–630 (1970).

Chattopadhyay, A. & Chatterjee, S. Risk indicators for recurrent aphthous ulcers among adults in the US. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 35, 152–159, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00329.x (2007).

Ciancio, G. et al. Nicotine-patch therapy on mucocutaneous lesions of Behcet’s disease: a case series. Rheumatology (Oxford) 49, 501–504, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kep401 (2010).

Kalayciyan, A. et al. Nicotine and biochanin A, but not cigarette smoke, induce anti-inflammatory effects on keratinocytes and endothelial cells in patients with Behcet’s disease. The Journal of investigative dermatology 127, 81–89, https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jid.5700492 (2007).

Kaklamani, V. G., Markomichelakis, N. & Kaklamanis, P. G. Could nicotine be beneficial for Behcet’s disease? Clin Rheumatol 21, 341–342 (2002).

Rizvi, S. W. & McGrath, H. Jr. The therapeutic effect of cigarette smoking on oral/genital aphthosis and other manifestations of Behcet’s disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol 19, S77–78 (2001).

Malek Mahdavi, A. et al. Cigarette smoking and risk of Behcet’s disease: a propensity score matching analysis. Mod Rheumatol, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1080/14397595.2018.1493065 (2018).

Aramaki, K., Kikuchi, H. & Hirohata, S. HLA-B51 and cigarette smoking as risk factors for chronic progressive neurological manifestations in Behcet’s disease. Mod Rheumatol 17, 81–82, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10165-006-0541-z (2007).

Ozer, H. T. et al. The impact of smoking on clinical features of Behcet’s disease patients with glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms. Clin Exp Rheumatol 30, S14–17 (2012).

Gallo, V. et al. Exploring causality of the association between smoking and Parkinson’s disease. Int J Epidemiol, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyy230 (2018).

Lee, P. C. et al. Smoking and Parkinson disease: Evidence for gene-by-smoking interactions. Neurology 90, e583–e592, https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000004953 (2018).

Arnson, Y., Shoenfeld, Y. & Amital, H. Effects of tobacco smoke on immunity, inflammation and autoimmunity. J Autoimmun 34, J258–265, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2009.12.003 (2010).

Berkowitz, L. et al. Impact of Cigarette Smoking on the Gastrointestinal Tract Inflammation: Opposing Effects in Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Front Immunol 9, 74, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00074 (2018).

Sari, Y. & Khalil, A. Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors Extracted from Tobacco Smoke as Neuroprotective Factors for Potential Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 14, 777–785 (2015).

Leroy, C. et al. Cerebral monoamine oxidase A inhibition in tobacco smokers confirmed with PET and [11C]befloxatone. J Clin Psychopharmacol 29, 86–88, https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0b013e31819e98f (2009).

Malczewska-Jaskola, K., Jasiewicz, B. & Mrowczynska, L. Nicotine alkaloids as antioxidant and potential protective agents against in vitro oxidative haemolysis. Chem Biol Interact 243, 62–71, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2015.11.030 (2016).

Laddha, N. C. et al. Role of oxidative stress and autoimmunity in onset and progression of vitiligo. Exp Dermatol 23, 352–353, https://doi.org/10.1111/exd.12372 (2014).

Schallreuter, K. U. et al. In vivo and in vitro evidence for hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) accumulation in the epidermis of patients with vitiligo and its successful removal by a UVB-activated pseudocatalase. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 4, 91–96 (1999).

Hann, S. K., Chang, J. H., Lee, H. S. & Kim, S. M. The classification of segmental vitiligo on the face. Yonsei medical journal 41, 209–212, https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2000.41.2.209 (2000).

Schallreuter, K. U. et al. Increased monoamine oxidase A activity in the epidermis of patients with vitiligo. Arch Dermatol Res 288, 14–18 (1996).

Zedan, H., Abdel-Motaleb, A. A., Kassem, N. M., Hafeez, H. A. & Hussein, M. R. Low glutathione peroxidase activity levels in patients with vitiligo. J Cutan Med Surg 19, 144–148, https://doi.org/10.2310/7750.2014.14076 (2015).

Sravani, P. V. et al. Determination of oxidative stress in vitiligo by measuring superoxide dismutase and catalase levels in vitiliginous and non-vitiliginous skin. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 75, 268–271, https://doi.org/10.4103/0378-6323.48427 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (NRF-2019R1F1A1056601). This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (NRF-2019R1F1A1056601). IRB approval status: Reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Uijeongbu St. Mary’s Hospital, Catholic University of Korea (UC18ZEISI0095)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Young Bok Lee, Ji Hyun Lee, and Yong Gyu Park participated in designing the study. Kyung Do Han and Yong Gyu Park participated in generating and gathering the data for the study. Young Bok Lee, Ji Hyun Lee, Soo Young Lee, Dong Soo Yu, Kyung Do Han, and Yong Gyu Park participated in the analysis of the data. All authors participated in writing the paper. All authors reviewed and approved all versions of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, Y.B., Lee, J.H., Lee, S.Y. et al. Association between vitiligo and smoking: A nationwide population-based study in Korea. Sci Rep 10, 6231 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63384-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63384-y

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.