Abstract

Honeybee colonies are under the threat of many stressors, biotic and abiotic factors that strongly affect their survival. Recently, great attention has been directed at chemical pesticides, including their effects at sub-lethal doses on bee behaviour and colony success; whereas the potential side effects of natural biocides largely used in agriculture, such as entomopathogenic fungi, have received only marginal attention. Here, we report the impact of the fungus Beauveria bassiana on honeybee nestmate recognition ability, a crucial feature at the basis of colony integrity. We performed both behavioural assays by recording bee guards’ response towards foragers (nestmate or non-nestmate) either exposed to B. bassiana or unexposed presented at the hive entrance, and GC-MS analyses of the cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs) of fungus-exposed versus unexposed bees. Our results demonstrated that exposed bees have altered cuticular hydrocarbons and are more easily accepted into foreign colonies than controls. Since CHCs are the main recognition cues in social insects, changes in their composition appear to affect nestmate recognition ability at the colony level. The acceptance of chemically unrecognizable fungus-exposed foragers could therefore favour forager drift and disease spread across colonies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bees are declining worldwide with considerable consequences on the pollination services they provide for crop production and the integrity of terrestrial ecosystems1,2,3. Agriculture intensification, pesticide exposure, and increased pressure of native and invasive parasites/pathogens have largely contributed to such decline1,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. As the adoption of intensive farming models aimed at feeding the world’s ever-growing population, cannot be separated from the massive use of agrochemicals11,12, in the last decades, an increasing effort has been dedicated to biological control strategies (biocontrol) to develop a more eco-friendly pest management approach in agriculture13,14,15. Nowadays, the use of microbial pathogens, parasites/parasitoids or predators to cope with insect pests, has partially replaced conventional synthetic plant-protection products in many countries12,15,16,17.

Among microbial pathogens, entomopathogenic fungi are extensively used as natural biocides in organic agriculture18,19,20,21,22,23. The worldwide-distributed Beauveria bassiana is a natural biocide widely used since the ‘80s19,21,22. This fungus attacks insects percutaneously: hydrophobic spores adhere to the cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs) layer, germinate and penetrate the insect cuticle, killing the host a few days after the infection20,21. The frequent use of B. bassiana as a biocontrol agent is justified by its proved efficacy on target pests and by the low cost compared to conventional chemical insecticides; notably, potential side effects on humans and other non-target organisms have so far been considered as negligible21.

Honeybees often forage on crops biologically controlled with B. baussiana24,25 therefore, spores of the fungus are likely to adhere to the insect body during the repeated foraging flights21,24,25 but such B. baussiana spore contamination does not seem to represent a threat for bee survival25,26. The apparent low sensitivity of insect pollinators, such as honeybees and bumblebees, to this entomopathogenic agent has even encouraged the possible use of bee foragers as vectors to disseminate fungal spores on crops against target insect pests24,25,27 or the direct spread of B. bassiana spores inside hives to control Varroa mite populations28,29.

In recent years a strong debate has developed about potential side effects of chemical biocides on non-target species, especially insect pollinators30,31,32,33. Sub-lethal doses of insecticides and pesticides have been reported to influence behavioural traits, such as flight capacity, orientation ability and memory in honeybees and bumblebees, which in turn affect foraging performance or the return of foragers to their colony31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40. In this framework, beside the importance of toxicological tests to evaluate the survival of target and not-target insects, it is also crucial to assess the potential effects of biocides on the behaviour of non-target species as well as on the complex interactions at the colony level of non-target social species.

Social insects have evolved a number of behavioural adaptations to restrict the diffusion of diseases inside the colony, which go under the name of social immunity41,42,43. Among these adaptive responses to pathogens, social insects recognize individuals from other colonies as well as sick colony members and avoid, exclude, isolate or even kill them41. Cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs), which are the cues at the basis of the recognition processes in social insects44, are also responsible for the discrimination of alien and sick or parasitized individuals45,46,47,48,49,50. The activation of the immune system, following an infection, can alter insect CHC profiles45,46,47,50. Consequently, biocontrol agents, including entomopathogenic fungi, can interfere with the colony recognition system in a subtle way by altering the individual chemical signature, as recently demonstrated in Myrmica scabrinodi naturally infected by ectoparasitic fungus Rickia wasmannii51,52 and in Lasius neglectus pupae artificially infected with Metarhizium brunneum50. If B. bassiana infection would cause similar alterations in bees, the allegedly safe biocontrol agents might have considerable effects on colony integrity and survival by impairing its recognition systems, therefore favouring the entering and the spread of parasites and pathogens among colonies vectored by drifting foragers.

In the present study, we investigated the effect of B. bassiana on the epicuticular hydrocarbon profile of fungus-exposed foragers and if these individuals are differently treated by guards at the hive entrance compared to unexposed conspecific individuals.

Results

Behavioural assays at the hive entrance

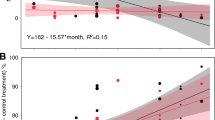

Guard bees at the hive entrance responded differently to the presented stimuli in the bioassays with freeze-killed lures and live bees exposed to B. bassiana spores (see Methods, Fig. 1). As expected, nestmates were attacked less than non-nestmates but exposed bees were in general less attacked than non-exposed individuals (significant effects for colony membership and exposure in Table 1). An important difference also emerged between experiments with a lower reaction toward lures compared to live bees and with the occurrence of a significant interaction between colony membership and exposure in the case of lure experiment (see below). The different results in the two experiments are likely due to the fact that in our first experiment with lures we tested only guards’ response to the stimuli chemical components involved in recognition, while in the second bioassay, with live freely-moving bees, the behavioural interactions between guards and the presented stimuli were also maintained. However, although the overall aggressive response was lower in the bee-lure experiment (Fig. 1a), in both cases with freeze-killed lures and live bees, exposure to B. bassiana spores had a significant effect on recognition and a decrease in the guards’ aggressive response towards fungus-exposed non-nestmate foragers was observed.

Presentation of lures experiment

A mixed model GLM showed that guard bees had a lower aggressive reaction toward nestmates (Table 1) and that the fungus exposure lowered the aggression (Table 1). Furthermore, fungus exposure interacted with nestmate recognition and fungus-exposed bees (both nestmates and non-nestmates) were subjected to a similar and intermediate level of aggression between unexposed nestmates and non-nestmates (Table 1, Fig. 1a).

Live bees experiment

A mixed GLM revealed that also in this experiment, guard bees had a lower aggressive reaction toward nestmates (Table 1, Fig. 1b) and the fungus exposure lowered the aggression (Table 1). However, in the case of live bee exposure and colony membership (nestmate, non-nestmate) did not show a significant interaction and fungus-exposed nestmates received a much lower aggression than fungus-exposed non-nestmates (Table 1, Fig. 1b).

Chemical analysis

To test whether bees showed any change in their epicuticular CHC profile after exposure to Beauveria bassiana, the CHC profile of fungus-exposed foragers was analysed with GC-MS. Analyses of the chromatograms for all the bees allowed the identification of 49 peaks corresponding to different compounds. The data set was reduced (see Methods) by cutting off 11 hydrocarbons; statistical analyses were thus performed on 38 compounds (Table 2). The identified compounds belong to four different classes: alkanes (N = 12), alkenes (N = 16), methyl-branched hydrocarbons (N = 1), esters between fatty acids and fatty alcohol (N = 8), plus one unidentified compound (Table 2).

No differences were found in the total amount of CHCs between unexposed and fungus-exposed foragers (GLM, t = −0.595, p = 0.5534). However, by considering the single compounds, we found that 6 alkenes (9-C23:1: t = −4.312, p < 0.0001; C23:2: t = −5.689, p < 0.0001; C24:1: t = −4.818, p < 0.0001; 9-C25:1: t = −2.957, p = 0.004; C25:2: t = −4.450, < 0.0001, p; and C27:2: t = −3.793, p = 0.0003) and 2 alkanes (n-C21: t = −2.890, p = 0.004; n-C22: t = −2.626, p = 0.010) were significantly lower in the fungus-exposed foragers than in the unexposed ones, while one alkane and one ester of palmitic acid was more abundant in the fungus-exposed bees (n-C27: t = 2.000, p = 0.048, palmitic acid ester 1: t = 2.452, p = 0.016) (Table 2).

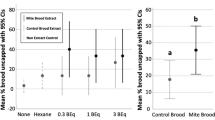

When plotted separately, the scores obtained by individuals of different colonies in a Partial Least Squares discriminant analyses, showed that unexposed individuals were characterized by a good separation based on the composition of their epicuticular lipids (Fig. 2a). Conversely, the scores obtained by fungus-exposed individuals revealed a much weaker diversification (Fig. 2b). Accordingly, a jackknife attribution of the specimens resulted in 63.4% of unexposed individuals correctly assigned to their colony against a 27.2% scored by fungus-exposed individuals. It must be noted that a random attribution of specimens to three colonies is expected to return a 33.3% of individuals correctly assigned by chance.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana, used as natural biocide in pest crop control, affects nestmate recognition in honeybees. As expected, guard bees at the hive entrance discriminated nestmate from non-nestmate foragers, being less aggressive toward unexposed nestmates. Interestingly, a reduction of the aggressive response was recorded when guards faced non-nestmate foragers experimentally exposed to the fungus B. bassiana. The decreased aggressive response towards exposed non-nestmates was observed when testing guards both with freeze-killed forager lures and with live foragers. With nestmate bees, instead, the guards’ reaction towards exposed individuals differed between the two experiments. In the experiment with freeze-killed lures, although the aggressive response was much lower than with live bees, exposed nestmates received a higher number of agonistic contacts when compared with unexposed ones at a rate that was comparable with exposed non-nestmates, Conversely, exposed live nestmates presented at the hive entrance received the lowest aggressive reactions by guards. Such a discordant result is most likely due to the different experimental protocols. In facts, it is plausible that in our first experiment with freeze-killed lures we tested exclusively the chemical cues involved in recognition. Guard bees might perceive the alteration in the chemical profile of their nestmates following fungus exposure which could prompt a relatively higher reaction towards them. In the case of live bees, fungus exposed individuals both nestmates and non-nestmates were less attacked compared to their unexposed controls and exposed nestmates received the lowest number of agonistic acts, while exposed non-nestmates were attacked at a rate that was comparable with unexposed nestmates. The lowered aggressive reaction of guards toward exposed bees regardless of colony membership is most likely due to the fact that live foragers presented at the hive entrance behaviourally interacted with the guards. If exposure to the fungus also altered their behaviour alongside their chemical profile, for example making exposed bees less reactive or aggressive, they could more easily sneak inside the colony. In facts, previous studies53,54 demonstrated that context or type of stimulus can have major effects on recognition. In the case of bees, guard are significantly more likely to make acceptance errors when tested in an unnatural context53, while the level of aggressive response can vary depending on the characteristics of presented stimulus as for example with Polistes wasps which show a lower degree of aggression when presented with only the cuticular fraction of a conspecific compared to a whole body wasp lure54. Overall, exposure to the fungus alters the CHCs of foragers bearing the mycosis after exposure to B. bassiana spores and this appears to be correlated to a significant change in the acceptance behaviour by guards towards fungus-exposed bees, especially increasing acceptance of exposed non-nestmates regardless of the experimental context, and such alteration.

Previous work on the CHCs dynamics on the tegument of insect hosts (Ostrinia nubilalis and Melolontha melolontha larvae) exposed to B. bassiana showed a high reduction (variable from 50% to 80% depending on the host) of the amount of such compounds within 96 h from infection55. Entomopathogenic fungi catabolize the long-chain hydrocarbons and penetrate inside the waxy cuticle of their insect hosts56,57 and such metabolic interactions may be responsible for the CHC alterations of mycosis-affected insects50,56,57.

By analysing the chemical profiles of fungus-exposed and unexposed foragers we found that differences between groups are mainly due to the different amount of six alkenes and two alkanes, which were consistently less abundant in fungus-exposed individuals, and one alkane and one ester of palmitic acid that was more abundant in the fungus-exposed bees rather than in the unexposed bees. The differential decrease in the alkene fraction in exposed individuals resulted in a homogenization of chemical profiles among colonies (Fig. 2) and it is likely at the basis of the observed reduction in aggressivity against exposed non-nestmates. This alteration of the hosts’ chemical profile may arise during the first phases of the infection process from the breakdown of hydrocarbons by B. bassiana58 or after infection due to an immune response affecting the synthesis of specific hydrocarbons45,46.

The selective reduction of specific alkenes is of particular interest, since it has been demonstrated that bees supplemented either with a synthetic mixture of alkenes or with the colony-specific alkenes fraction, are treated more aggressively by nestmate guards than control bees or nestmates applied either with a synthetic mixture of alkanes or with the colony-specific alkanes fraction59. Such findings indicate that alkenes play a crucial role in nestmate recognition in honeybees and that the relative increase of such compounds on the cuticle of incoming foragers elicits aggressive behaviour in guards, preventing them from recognizing nestmates59. Indeed, alkenes appear to be responsible for differences in the average chemical profile of different honeybee colonies as well as other social hymenoptera60. Moreover, alkenes have been found to be more easily learned and discriminated in PER (proboscis extension reflex) trained bees with respect to alkanes60,61. Thus, the lower amount of the six specific alkenes found on the cuticular profile of B. bassiana-exposed bees, with respect to unexposed ones, are most likely responsible for the higher degree of acceptance of guard bees towards fungus-exposed non-nestmate foragers with respect to unexposed non-nestmate ones.

Recent work has demonstrated that the selective increase of specific alkenes in pupae of the ant Lasius neglectus exposed to the enthomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium brunneum induce the killing of infected brood during the non-transmissible incubation period of the pathogen50. Our bees exposed to Beauveria showing a selective reduction in alkenes might instead be depleted of those compounds relevant for colony discrimination60,61. Such a modification interferes with the nestmate recognition system and guard bees at the hive entrance are unable to correctly assess foragers affected by the mycosis.

Several bee parasites have evolved adaptive strategies based on chemical mimicry to their host: Varroa mites, for instance, show an almost perfect colony specific mimicry with their host to avoid detection62,63,64,65. Chemical mimicry, replicating the colony specific pattern of CHCs, has also been reported for the death’s head hawkmoth Acherontia atropos and the parasitic fly Braula coeca66,67, and appears to be widespread in social insect parasites mimicking the host chemical profile to favour their spread and survival inside colonies67. Since B. bassiana is an unspecific insect pathogen, the modification of cuticular hydrocarbon profile observed in our fungus-exposed bees may be a mere by-product of the pathogen’s metabolism56,57,58 rather than an adaptive strategy evolved to infect honeybee colonies; nevertheless the selective decrease of cuticular olefins in our fungus-exposed bees could represent a serious threat for colony integrity.

Artificial infection with the non-specific pathogen E. coli also alters the cuticular profile of bee workers, but such changes did not consist of a selective reduction of the alkene fraction and the resulting alterations in cuticular profiles elicited an increase in the nestmates’ aggressive response towards bacteria-injected individuals46. A significant change in the CHC profile of honeybees has also been reported for workers infected with deformed wing virus (DWV) which are detected and removed from the colony47, however, also in this case, the chemical alteration involves different fractions of the cuticular compounds rather than the specific alkene fraction important for nestmate recognition59.

Overall, our results showed a clear disrupting effect of B. bassiana on the nestmate recognition system of honey bees, potentially favouring the drift of foragers to alien colonies and in turn the potential spread of parasites and pathogens. Indeed, an efficient nestmate recognition system is crucial for honey bee colonies as it limits drifting and robbing behaviour68, which are the main causes for the spread of infectious diseases, such as varroatosis, foulbrood and nosemosis69,70,71. Foragers carrying the fungal pathogen Nosema ceranae are even more prone to drift toward nearby hives than uninfected ones71. Given the use of B. bassiana as a natural biocide in organic agriculture and the possible use of pollinators as vectors for microorganisms in biocontrol19,21,24,25, future research should aim at investigating whether foragers exposed to the fungus spores show an altered behaviour (i.e. higher degree of drifting) with respect to unexposed bees.

Many recent efforts to limit the use of chemical pesticides and to adopt more sustainable agricultural models have led to a considerable increase in the use of bio-insecticides for pest management13,14,17. Although the adoption of natural biocides is desirable, we showed that treatments with the allegedly safe B. bassiana interfere with nestmate recognition in honeybees, possibly fostering inter-colony transmission of diseases. We thus warn that natural biocides used for pest management should not only be tested for their direct toxicity at the individual level on target and non-target species. The same attention should be dedicated to carefully testing for side effects on non-target ecologically relevant social insect species to understand the potential effects on those behavioural features linked to complex social organization determining the colony health status and survival.

Methods

Bee sample collection and experimental hives

Bee sample collections and behavioural field assays were carried out on hives of 3 experimental apiaries separated by at least 35 km from each other in the surroundings of Florence (Italy) (apiary A: 50 colonies; apiary B: 5 colonies; apiary C: 10 colonies). All the colonies used for the experiments were queen-right and housed in Dadant-Blatt boxes. All behavioural experiments and collections were carried out during spring and summer 2015 and 2016, between May and July.

Isolation and culturing of Beauveria bassiana strains

B. bassiana (Balsamo) Vuillemin infective conidiospores (conidia) were isolated from the commercial product Naturalis® (Intrachem Bio Italia), a bioinsecticide based on living conidiospores of the naturally occurring B. bassiana strain ATCC 74040, isolated from Anthonomus grandis (Boheman), the cotton boll weevil. The formulated product contains at least 2.3 × 107 viable spores/ml. Petri dishes with Malt Extract Agar (MEA, Oxoid) were plated with 100 μl of commercial product and incubated for three days at 30 °C. Fungal conidia emerging on plates were collected and re-suspended in a 0.01% Triton X-100-water solution at a concentration of 109 spores/ml. Spore concentration was checked through vital count after plating different dilutions on MEA incubated for three days at 30 °C.

Behavioural assays

Behavioural assays were performed, by using two different procedures, to test whether guard bees at the hive entrance are able to recognize fungus-exposed nestmate/non-nestmate foragers. The first bioassay consisted of presentation of lures at the hive entrance, where the importance of the mere chemical cues for recognition was tested. The second bioassay consisted of a more natural condition in which guard bees had to recognize fungus-exposed or unexposed live foragers induced to approach the hive entrance72; in this experiment, the behavioural components are maintained alongside the chemical ones. All the experiments were carried out in accordance with Italian laws and regulations.

Presentation of lures experiment

-

i)

Lure preparation: forager bees were collected at the hive entrance while departing for their foraging flights (20 foragers per hive; 28 hives from apiary A; four hives from apiary C). Foragers were then brought to the laboratory, about half of the collected bees for each colony were exposed to the fungus by applying 1 μl of a 0.01% Triton X-100-water solution, containing about 106 conidia of B. bassiana, on their thorax by using a 2 μl micropipette. We chose to use this concentration, corresponding to 109 conidia/ml, since it appears similar or lower to those of the solution commonly sprayed in the field for pest biocontrol19 or pollinator biocontrol vector technology24,25,27. The other half of the foragers was applied with 1 μl of triton-water solution, containing no fungus conidia using the same procedure. Experimental and control bees were separated based on treatment and colony of origin in 7 cm Petri dishes, supplied with honey and water ad libitum for three days. A period of three days is sufficient for the fungus to reach the hemolymph and trigger an immune response21,73, potentially inducing detectable changes in epicuticular CHCs, which could in turn affect the bee guards’ response46,47,48,49,72,74,75. Foragers were kept in the dark, under controlled laboratory conditions (28–29 °C T, 55–65% RH); bees that died during treatment were daily removed from each dish. After three days, bees were killed by freezing and brought to the apiary A for field bioassays.

-

ii)

Lure presentation: to perform the behavioural assay we followed a procedure similar to that used by Cappa et al.76: each of the selected colonies (N = 28) in apiary A was presented with four stimuli in a random sequence: two nestmate and two non-nestmate foragers from apiary C either unexposed or exposed to the fungus three days before the behavioural assays. Each lure was fixed to a small clip at the top of a 40 cm thin metal rod, slowly brought near to the hive entrance, and gently moved alongside the flight board contacting as many bees as possible in order to record their reactions76. Each presentation lasted 1 min starting from the first interaction of a bee with the lure. To avoid habituation effects, assays were performed on a same colony with at least a 15-min interval between each other. All the assays were carried out on a single day, between 10:00 and 16:00. All the assays were videotaped. Each lure was used only once and we carried out a total of 112 assays.

Videotapes were blind-watched in slow motion (0.25 s) by a viewer who noted the total number of bees interacting with each lure and the total number of agonistic contacts (biting, stinging) of resident bees towards the lure. As the lure was actively moved on the flight board to record the reactions of the highest possible number of bees, which could vary during the 1-minute assay, the average number of bees at the entrance was calculated by counting the number of bees on the flight board at the beginning and at the end of presentation76.

We used the “glmmadmb” function in the “glmmADMB” package (http://glmmadmb.r-forge.r-project.org/) to fit a Generalized Linear Mixed Model using a Poisson distribution. As predictor variables we used i) average number of bees at the entrance, ii) colony membership (alien vs nestmate), iii) exposure to B. bassiana as fixed factors together with the iv) interaction between colony merandom factor.

Live bee experiment

The following year, a different behavioural assay was performed by presenting live foragers to the colonies. These presented foragers were: a) unexposed nestmates, b) unexposed non-nestmates, c) fungus-exposed nestmates, d) fungus-exposed non-nestmates. Nestmate foragers (apiary B) and alien foragers (apiary C) were collected and treated following the same procedure described in the lure presentation experiment. Three days after the exposure with B. bassiana, both exposed and unexposed bees were individually placed into eppendorf tubes and carried to apiary A for the bioassay. Tubes were kept for several minutes in a ice-cooled styrofoam box before presentations, in order to calm down the experimental bees, therefore preventing them from fidgeting or flying away once freed from the tubes57,72,74. When the assay started, each focal bee was gently released on the landing board and was free to move, to interact with other bees, to enter the hive or fly away. Bee guards’ reactions were recorded for 3 minutes after the first interaction. When the focal bee entered the hive, or flew away without interacting with guards the assay was discarded. The videotaped assays were blind-watched to record the number and the duration of each agonistic interaction (biting, stinging) among focal bees and guards on the landing board. A total of 259 assays (108, 65, 86 respectively on hives a, b and c in apiary B) were performed (Table S1). We modelled the number of agonistic acts with the same design of the same Generalized Linear Mixed Model and contrast analysis as described above.

Chemical analyses

Data collection

We collected 100 foragers from the three tested colonies a, b and c (at least 30 bees per colony) in the experimental apiary B. Following exactly the same procedure used for bioassays, we exposed half of these bees to B. bassiana conidia while the remaining half were used as control and received only the 0.01% Triton X-100-water solution. Experimental and control bees were separated by treatment and colony in 7 cm Petri dishes, supplied with honey and water ad libitum for three days. All the bee groups were maintained in the dark, under controlled laboratory conditions. Three days after the bees were killed by freezing for subsequent chemical analyses. Before the analyses, each bee was thawed, then the apolar fraction of the cuticular compounds of each worker (N = 85, 44 fungus-exposed, 41 unexposed controls) was extracted by washing the entire body for 10 min in 1 ml of pentane. The extracts were dried under a stream of nitrogen and then re-suspended in 10 µl of heptane with 70 ng/μl of heptadecane (n-C17) as internal standard. One μl of extract was injected in a Hewlett Packard (Palo Alto,CA, U.S.A.) 5890 A gas chromatograph (GC) coupled to an HP 5970 mass selective detector (using 70 eV electronic ionization source). A fused ZB-WAX-PLUS (Zebron) silica capillary column (60 m x 0.25 mm × 0.25 mm) was installed in the GC. The injector port and transfer line temperatures were set at 200 °C and the carrier gas was helium (at 20 PSI head pressure). The temperature protocol was: from 50 °C to 320 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min and the final temperature was kept for 5 minutes. Injections were performed in splitless mode (1 min purge valve off). Data acquisition and analysis were done using the Chem Station G1701 BA (version B.01.00) - Copyright © Hewlett-Packard 1989–1998.

CHCs were identified on the basis of their mass spectra, and equivalent chain length. For the preparation of the dataset used in statistical analysis we only included compounds quantified in at least 25% of specimens with the exception of compounds only identified in one of the treatment groups (exposed/unexposed). We used Mixed-effects models for repeated-measures ANOVA (glmmPQL function of the MASS R package) to evaluate differences both in the total amount of cuticular hydrocarbons present in the extracts and in the amount of single compounds between fungus-exposed and control bees; colony membership was included as a random factor. Multivariate analyses have been applied to the dataset to verify the possibility of attributing fungus-exposed and unexposed specimens to their colony based on chemical composition. With this aim we first performed a Partial Least Square Discriminant analysis using colony membership as a priori grouping variable. This allowed us to visualize the general pattern of similarity among individuals. The possibility to attribute specimens to their colonies has been tested by a jackknife procedure where a Partial Least Square Discriminant analysis has been performed on all the uninfected specimens but one. Then the colony membership of the excluded specimen and of one fungus-exposed individual (in random order) has been predicted on the basis of their CHCs composition. We used the percentage of correctly attributed cases as a measure of the possibility to blindly attribute fungus-exposed and unexposed individuals to their colonies.

Data Availability

Data files and R script used are uploaded alongside supplementary material.

References

Watanabe, M. E. Pollination worries rise as honey bees decline. Science 265, 1170–1171 (1994).

Klein, A. M. et al. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proc. R. Soc. B 274, 303–313, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3721 (2007).

Calderone, N. W. Insect pollinated crops, insect pollinators and US agriculture: trend analysis of aggregate data for the period 1992-2009. PloS one 7, e37235, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037235 (2012).

vanEngelsdorp, D. et al. Colony collapse disorder: a descriptive study. PLoS One 4, e6481, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0006481 (2009).

Ellis, J. D., Evans, J. D. & Pettis, J. S. Colony losses, managed colony population decline and Colony Collapse Disorder in the United States. J. Apic. Res. 49, 134–136, https://doi.org/10.3896/IBRA.1.49.1.30 (2010).

Neumann, P. & Carreck, N. L. Honey bee colony loss. J. Apic. Res. 49, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.3896/IBRA.1.49.1.01 (2010).

Potts, S. G. et al. Declines of managed honey bees and beekeepers in Europe. J. Apic. Res. 49, 15–22, https://doi.org/10.3896/IBRA.1.49.1.02 (2010).

Potts, S. G. et al. Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 345–353, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2010.01.007 (2010).

Nazzi, F. et al. Synergistic parasite-pathogen interactions mediated by host immunity can drive the collapse of honeybee colonies. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002735, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002735 (2012).

Staveley, J. P., Law, S. A., Fairbrother, A. & Menzie, C. A. A causal analysis of observed declines in managed honey bees (Apis mellifera). Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 20, 566–591, https://doi.org/10.1080/10807039.2013.831263 (2014).

Oerke, E. C. & Dehne, H. W. Safeguarding production-losses in major crops and the role of crop protection. Crop. Prot. 23, 275–285, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2003.10.001 (2004).

Damalas, C. A. & Eleftherohorinos, I. G. Pesticide exposure, safety issues, and risk assessment indicators. Int. J. Env. Res. Publ. Health 8, 1402–1419, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8051402 (2011).

Cook, R. J. et al. Safety of microorganisms intended for pest and plant disease control: a framework for scientific evaluation. Biol. Cont. 7, 333–351, https://doi.org/10.1006/bcon.1996.0102 (1996).

Lacey, L. A., Frutos, R., Kaya, H. K. & Vail, P. Insect pathogens as biological control agents: do they have a future? Biol. Cont. 21, 230–248, https://doi.org/10.1006/bcon.2001.0938 (2001).

Jackson, M. A., Dunlap, C. A. & Jaronski, S. T. Ecological considerations in producing and formulating fungal entomopathogens for use in insect biocontrol. BioControl 55, 129–145, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-009-9240-y (2010).

Butt, T. M., Jackson, C. & Magan, N. Fungi as biocontrol agents: progress problems and potential. (CABI, 2001).

Whipps, J. M. & Lumsden, R. D. Commercial use of fungi as plant disease biological control agents: status and prospects. Fungal biocontrol agents: progress, problems and potential, pp. 9–22 (2001).

Goettel, M. S. & Roberts, D. W. Mass production, formulation and field application of entomopathogenic fungi. In Lomer, C. J. & Prior, C. (eds) Biological control of locusts and grasshoppers. pp 230–238, (CAB International, Wallingford, 1992).

Feng, M. G., Poprawski, T. J. & Khachatourians, G. G. Production, formulation and application of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana for insect control: current status. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 4, 3–34, https://doi.org/10.1080/09583159409355309 (1994).

Shah, P. A. & Pell, J. K. Entomopathogenic fungi as biological control agents. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 61, 413–423, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-003-1240-8 (2003).

Zimmermann, G. Review on safety of the entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana and Beauveria brongniartii. Biocontrol. Sci. Technol. 17, 553–596, https://doi.org/10.1080/09583150701309006 (2007).

Mascarin, G. M. & Jaronski, S. T. The production and uses of Beauveria bassiana as a microbial insecticide. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 32, 177, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-016-2131-3 (2016).

McKinnon, A. C. et al. Beauveria bassiana as an endophyte: a critical review on associated methodology and biocontrol potential. BioControl 62, 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-016-9769-5 (2017).

Kevan, P. G. et al. Using pollinators to deliver biological control agents against crop pests. In Downer, R. A., Mueninghoff, J. C., Volgas, G. C. (Eds) Pesticide formulations and delivery systems: Meeting the challenges of the current crop protection industry, pp. 148–152 (West Conshohocken. PA: American Society for Testing and Materials International, 2003).

Al-Mazra’awi, M. S., Kevan, P. G. & Shipp, L. Development of Beauveria bassiana dry formulation for vectoring by honey bees Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae) to the flowers of crops for pest control. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 17, 733–741, https://doi.org/10.1080/09583150701484759 (2007).

Vandenberg, J. D. Safety of four entomopathogens for caged adult honey bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 83, 755–759, https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/83.3.755 (1990).

Kevan, P. G., Kapongo, J., Al-mazra’awi, M. & Shipp, L. Honey bees, bumble bees and biocontrol. Bee pollination in agriculture ecosystems. (Oxford University Press, New York, 2008).

Meikle, W. G., Mercadier, G., Holst, N., Nansen, C. & Girod, V. Duration and spread of an entomopathogenic fungus, Beauveria bassiana (Deuteromycota: Hyphomycetes), used to treat varroa mites (Acari: Varroidae) in honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) hives. J. Econ. Entomol. 100, 1–10 (2007).

Meikle, W. G., Mercadier, G., Holst, N. & Girod, V. Impact of two treatments of a formulation of Beauveria bassiana (Deuteromycota: Hyphomycetes) conidia on Varroa mites (Acari: Varroidae) and on honeybee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) colony health. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 46, 105, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-008-9160-z (2008).

El-Wakeil, N., Gaafar, N., Sallam, A. & Volkmar, C. Side effects of insecticides on natural enemies and possibility of their integration in plant protection strategies. In Insecticides-development safer and more effective technologies. InTech. (2013).

Godfray, H. C. J. et al. A restatement of the natural science evidence base concerning neonicotinoid insecticides and insect pollinators. Proc. R. Soc.B 281, 20140558, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.0558 (2014).

Sanchez-Bayo, F. & Goka, K. Impacts of pesticides on honey bees. In Beekeeping and Bee Conservation-Advances in Research. InTech (2016).

Alkassab, A. T. & Kirchner, W. H. Sublethal exposure to neonicotinoids and related side effects on insect pollinators: honeybees, bumblebees, and solitary bees. J. Plant. Dis. Protect. 124, 1–30, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41348-016-0041-0 (2017).

Vandame, R., Meled, M., Colin, M. E. & Belzunces, L. P. Alteration of the homing-flight in the honey bee Apis mellifera L. exposed to sublethal dose of deltamethrin. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 14, 855–860, https://doi.org/10.1897/1552-8618 (1995).

Yang, E. C., Chuang, Y. C., Chen, Y. L. & Chang, L. H. Abnormal foraging behavior induced by sublethal dosage of imidacloprid in the honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 101, 1743–1748, https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-0493-101.6.1743 (2008).

Henry, M. et al. A common pesticide decreases foraging success and survival in honey bees. Science 336, 348–350, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1215039 (2012).

Schneider, C. W., Tautz, J., Grünewald, B. & Fuchs, S. RFID tracking of sublethal effects of two neonicotinoid insecticides on the foraging behavior of Apis mellifera. PLoS one 7, e30023, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0030023 (2012).

Fischer, J. et al. Neonicotinoids interfere with specific components of navigation in honeybees. PLoS one 9, e91364, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0091364 (2014).

Charreton, M. et al. A locomotor deficit induced by sublethal doses of pyrethroid and neonicotinoid insecticides in the honeybee Apis mellifera. PloS one 10, e0144879, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0144879 (2015).

Tosi, S., Burgio, G. & Nieh, J. C. A common neonicotinoid pesticide, thiamethoxam, impairs honey bee flight ability. Sci. Rep. 7, 1201, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01361-8 (2017).

Cremer, S., Armitage, S. A. & Schmid-Hempel, P. Social immunity. Curr. Biol. 17, R693–R702, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.008 (2007).

Cremer, S. & Sixt, M. Analogies in the evolution of individual and social immunity. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 129–142, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2008.0166 (2009).

Cotter, S. C. & Kilner, R. M. Personal immunity versus social immunity. Behav. Ecol. 21, 663–668, https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arq070 (2010).

vanZweden, J. S. & d’Ettorre, P. Nestmate recognition in social insects and the role of hydrocarbons. In Blomquist, G. J. & Bagnères, A. G. (Eds) Insect hydrocarbons: biology, biochemistry and chemical ecology, pp. 222–243 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010).

Richard, F. J., Aubert, A. & Grozinger, C. M. Modulation of social interactions by immune stimulation in honey bee, Apis mellifera, workers. BMC Biol. 6, 50, https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-6-50 (2008).

Richard, F. J., Holt, H. L. & Grozinger, C. M. Effects of immunostimulation on social behavior, chemical communication and genome-wide gene expression in honey bee workers (Apis mellifera). BMC Genomics 13, 558, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-13-558 (2012).

Baracchi, D., Fadda, A. & Turillazzi, S. Evidence for antiseptic behaviour towards sick adult bees in honey bee colonies. J. Insect Physiol. 58, 1589–1596, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2012.09.014 (2012).

McDonnell, C. M. et al. Ecto-and endoparasite induce similar chemical and brain neurogenomic responses in the honey bee (Apis mellifera). BMC Ecol. 13, 25, https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6785-13-25 (2013).

Cappa, F., Bruschini, C., Protti, I., Turillazzi, S. & Cervo, R. Bee guards detect foreign foragers with cuticular chemical profiles altered by phoretic varroa mites. J. Api. Res. 55, 268–277, https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2016.1229886 (2016).

Pull, C. D. et al. Destructive disinfection of infected brood prevents systemic disease spread in ant colonies. eLife 7 (2018).

Markó, B. et al. Distribution of the myrmecoparasitic fungus Rickia wasmannii (Ascomycota: Laboulbeniales) across colonies, individuals, and body parts of Myrmica scabrinodis. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 136, 74–80, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2016.03.008 (2016).

Csata, E. et al. Lock-picks: fungal infection facilitates the intrusion of strangers into antcolonies. Sci. Rep. 7, 46323, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46323 (2017).

Couvillon, M. J., Boniface, T. J., Evripidou, A. M., Owen, C. J. & Ratnieks, F. L. Unnatural contexts cause honey bee guards to adopt non‐guarding behaviours towards allospecifics and conspecifics. Ethology 121, 410–418 (2015).

Cappa, F., Beani, L. & Cervo, R. The importance of being yellow: visual over chemical cues in gender recognition in a social wasp. Behav. Ecol. 27, 1182–1189 (2016).

Lecuona, R., Riba, G., Cassier, P. & Clement, J. L. Alterations of insect epicuticular hydrocarbons during infection with Beauveria bassiana or B. brongniartii. J. Invert. Pathol. 58, 10–18, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2011(91)90156-K (1991).

Ortiz-Urquiza, A. & Keyhani, N. O. Action on the surface: entomopathogenic fungi versus the insect cuticle. Insects 4, 357–374, https://doi.org/10.3390/insects4030357 (2013).

Pedrini, N., Crespo, R. & Juárez, M. P. Biochemistry of insect epicuticle degradation by entomopathogenic fungi. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 146, 124–137, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpc.2006.08.003 (2007).

Lin, L. et al. The MrCYP52 cytochrome P450 monoxygenasegene of Metarhizium robertsii is important for utilizing insect epicuticular hydrocarbons. PLoS one 6, e28984, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0028984 (2011).

Dani, F. R. et al. Nestmate recognition cues in the honey bee: differential importance of cuticular alkanes and alkenes. Chem Senses 30, 477–489, https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bji040 (2005).

Kather, R. & Martin, S. J. Evolution of cuticular hydrocarbons in the hymenoptera: a meta-analysis. J. Chem. Ecol. 41, 871–883, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-015-0631-5 (2015).

Châline, N., Sandoz, J. C., Martin, S. J., Ratnieks, F. L. & Jones, G. R. Learning and discrimination of individual cuticular hydrocarbons by honeybees (Apis mellifera). Chem. Senses 30, 327–335, https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bji027 (2005).

Le Conte, Y. et al. Varroa destructor changes its cuticular hydrocarbons to mimic new hosts. Biol. Lett. 11, 20150233, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2015.0233 (2015).

Kather, R., Drijfhout, F. P., Shemilt, S. & Martin, S. J. Evidence for passive chemical camouflage in the parasitic mite Varroa destructor. J. Chem Ecol. 41, 178–186, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-015-0548-z (2015).

Kather, R., Drijfhout, F. P. & Martin, S. J. Evidence for colony-specific differences in chemical mimicry in the parasitic mite Varroa destructor. Chemoecology 25, 215–222, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00049-015-0191-8 (2015).

Moritz, R. F. A., Kirchner, W. H. & Crewe, R. M. Chemical camouflage of the death’s head hawkmoth (Acherontia atropos L.) in honeybee colonies. Naturwissenschaften 78, 179–182, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01136209 (1991).

Martin, S. J. & Bayfield, J. Is the bee louse Braula coeca (Diptera) using chemical camouflage to survive within honeybee colonies? Chemoecolgy 24, 165–169, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00049-014-0158-1 (2014).

Bagnères, A. G. & Lorenzi, M. C. Chemical deception/mimicry using cuticular hydrocarbons. In Blomquist, G. J., Bagnères, A. G. (Eds) Insect hydrocarbons: biology, biochemistry and chemical ecology, pp. 282–323 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010).

Free, J. B. The drifting on honey-bees. J. Agric. Sci. 51, 294–306 (1958).

Goodwin, R. M., Perry, J. H. & Houten, A. T. The effect of drifting honey bees on the spread of American foulbrood infections. J. Apic. Res. 33, 209–212, https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.1994.11100873 (1994).

Fries, I. & Camazine, S. Implications of horizontal and vertical pathogen transmission for honey bee epidemiology. Apidologie 32, 199–214, https://doi.org/10.1051/apido:2001122 (2001).

Bordier, C., Pioz, M., Crauser, D., Le Conte, Y. & Alaux, C. Should I stay or should I go: honeybee drifting behaviour as a function of parasitism. Apidologie 48, 286–297, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-016-0475-1 (2016).

Downs, S. G. & Ratnieks, F. L. Adaptive shifts in honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) guarding behavior support predictions of the acceptance threshold model. Behav. Ecol. 11, 326–333, https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/11.3.326 (2000).

Vilcinskas, A. & Götz, P. Parasitic fungi and their interactions with the insect immune system. Adv. Parasit. 43, 267–313, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-308x(08)60244-4 (1999).

Downs, S. G., Ratnieks, F. L., Badcock, N. & Mynott, A. Honey bee guards do not use food derived odours to recognise non-nestmates: a test of the odour convergence hypothesis. Behav. Ecol. 12, 47–50, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.beheco.a000377 (2001).

Cervo, R. et al. High Varroa mite abundance influences chemical profiles of worker bees and mite–host preferences. J. Exp. Biol. 217, 2998–3001, https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.099978 (2014).

Cappa, F., Bruschini, C., Cipollini, M., Pieraccini, G. & Cervo, R. Sensing the intruder: a quantitative threshold for recognition cues perception in honeybees. Naturwissenschaften 101, 149–152, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-013-1135-1 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. B. Taylor for critical reading and English revision and Dr. D. Venancio and Dr. P. Dori for their help in the behavioural assays in the field. The authors also thank two anonymous reviewers and all the members of the Florence Group for the Study of Social Insects for fruitful discussions on the topic. Financial support was provided by the project Programmi di Ricerca di Rilevante Interesse Nazionale (PRIN) 2012 (prot. 2012RCEZWH_001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.C., I.P. and R.C. conceived of and designed the experiments. F.C., I.P., M.G. and J.S.C. carried out the behavioural assays. I.P., F.R.D. and L.D. performed chemical analysis and designed and conducted statistical analysis. R.C. and S.T. provided material, facilities and reagents. F.C., I.P., R.C., F.R.D. and L.D. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cappa, F., Petrocelli, I., Dani, F.R. et al. Natural biocide disrupts nestmate recognition in honeybees. Sci Rep 9, 3171 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-38963-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-38963-3

This article is cited by

-

A predatory social wasp does not avoid nestmates contaminated with a fungal biopesticide

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

-

Natural infection potential and efficacy of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana against Orosanga japonica (Melichar)

Egyptian Journal of Biological Pest Control (2020)

-

Increased immunocompetence and network centrality of allogroomer workers suggest a link between individual and social immunity in honeybees

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Exposure to a biopesticide interferes with sucrose responsiveness and learning in honey bees

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.