Abstract

Cognition dysfunction may reflect trait characteristics of bipolarity but cognitive effects of medications have confounded previous comparisons of cognitive function between bipolar II and unipolar depression, which are distinct clinical disorders with some overlaps. Therefore, we examined the executive function (WCST), attention, cognitive speed (TMT-A) and memory (CAVLT, WMS-Visual reproduction) of 20 treatment-naïve bipolar II patients (BPII), 35 treatment-naïve unipolar depressed (UD) patients, and 35 age/sex/education matched healthy controls. The subjects were young (aged 18–35), and had no history of psychosis or substance use, currently depressed and meeting either RDC criteria for Bipolar II Disorder or DSM-IV-TR criteria for Major Depressive Disorder. The patients were moderately depressed (MADRS) and anxious(HAM-A), on average within 3.44 years of illness onset. Sociodemographic data and IQ were similar between the groups. UD patients had significantly slower cognitive speed and cognitive flexibility (WCST perseverative error). BPII depressed patients showed relatively intact cognitive function. Verbal memory (CAVLT List A total) correlated with illness chronicity only in BPII depression, but not UD. In conclusion, young and treatment-naïve BPII depressed patients differed from unipolar depression by a relatively intact cognitive profile and a chronicity-cognitive correlation that suggested a stronger resemblance to Bipolar I Disorder than Unipolar Depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Controversy exists as to the extent cognitive impairment found in Bipolar Disorders1 reflect trait characteristics for bipolarity2,3,4 or indicate neuroprogressive consequences of chronicity and episodic recurrence3,5. This is partly because of the methodological difficulty of recruiting drug-naïve patients. Yet, since both mood stabilisers and antipsychotic drugs, commonly used in the long-term treatment of bipolar disorders, have varied effects on cognition6, recruiting drug-naïve and ideally younger patients is essential for clarifying the inconclusive findings.

Another way to elucidate the role of cognitive impairment in bipolar disorders is to examine such impairment in bipolar II (BPII) depression vs unipolar depression (UD). BPII is the commonest bipolar subtype, but where diagnostic controversy frequently exists owing to its clinical features which often overlap with unipolar depression. The illness courses in both of the disorders are predominated by depressive states7. Up to one-third of patients diagnosed with UD would meet criteria for BPII8, and one-fifth would have diagnostic conversion to BPII in 5 years9,10. Increased chronicity and recurrent depressive phases7, reverse vegetative symptoms, mood reactivity, as well as antidepressant non-response in bipolar II depression, on the other hand, suggest a different pathophysiological substrate than UD11. It is therefore noteworthy that, in contrast to studies of depressed and medicated BPII patients which found impaired sustained attention12 and executive function13, Taylor Tavares et al.14 found the cognitive function of currently unmedicated BPII depressed patients (n = 17) to be relatively intact compared to unipolar depressed patients (n = 22). Unlike BPII patients, the latter showed prominent deficits including spatial working memory, attentional shifting, and tendency to sample loss trials on a gamble test. The patients in this study had, however, received psychotropic treatment in the past, with an average of 15–18 years of illness. The different types of medications (antidepressants versus mood stabilisers) received by unipolar and bipolar patients may have different sustained impact on the cognitive function studied. Common reasons for cessation of treatment in patients with bipolar disorders (e.g. impaired insight, secondary non-compliance when mental state was poor, or a relatively benign illness course rendering patients less committed to the need for continued psychopharmacological maintenance) may also have influenced the cognitive functions measured. With the long past illness histories and previous pharmacotherapy in these patients, it would also be more difficult to attribute results from the study to inherent endophenotypic differences between bipolar and unipolar depression.

Published data on cognitive function in BP-II depressed patients, apart from Tavares Taylor et al., are rare. We therefore set out to examine the cognitive function of young and treatment-naïve bipolar II and unipolar depressive patients with no history of psychosis or substance use, versus age/sex-matched controls to better elucidate trait-related variation in cognitive function in bipolar II disorder. They were then compared with age/sex-matched healthy controls. Our objectives were:

-

1.

To examine the nature and differences of cognitive impairment in drug-naïve and young BPII depressed and unipolar depressed patients

-

2.

To explore in BPII depressed and unipolar depressed patients the correlation between cognitive impairment with illness chronicity and current affective symptoms

Results

In the years 2014–2017, 20 treatment-naïve and currently depressed subjects with Bipolar II Disorder (BPII), 35 treatment-naïve and currently depressed subjects with Major Depressive Disorder (UD) and 35 healthy controls (HC) were systematically recruited. The BPII, UD and HC groups were comparable in age, gender and other socio-demographic variables including occupational status, marital status and family income. (Table 1).

Clinical symptom and course

The BPII and UD subjects had MADRS and HAM-A scores of moderate severity, significantly higher than HC (ps < 0.001), but not significantly different between BPII and UD (ps > 0.05). Current average YMRS score in BPII subjects was low (4.30). UD and BPII subjects were comparable in the significantly reduced SF-36 physical and mental component summary scores compared to healthy controls (ps < 0.001), reflecting impaired health-related quality of life (Table 2). BPII subjects had significantly earlier age of depressive onset than UD (p = 0.01), significantly longer time since first depressive onset (p = 0.01) and significantly more major depressive episodes than UD (p = 0.02). BPII subjects had on average 71.65 lifetime hypomanic episodes (six of the subjects reported more than monthly hypomanic episodes in at least 5 years of illness).

Cognitive Variables

The average estimated IQ scores in the BPII, UD and HC groups were similar. (Table 3). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed a main effect of HC/UD/BPII grouping on processing speed (TMT-A time to completion) (p < 0.001). Post-hoc Bonferroni correction showed significantly slower psychomotor speed (TMT-A completion) in UD compared to BPII (p = 0.001) and HC (p < 0.001) but indistinguishable between BPII subjects and HC. In a logistic regression model controlled for age, gender, years of education, current depression, mania and anxiety severity, lifetime number of depressive episodes and illness chronicity, TMT-A completion (p = 0.02, AOR = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.74–0.97) and lifetime number of depressive episodes (p = 0.02, AOR = 3.34, 95%CI: 0.84–1.06) significantly differentiated the BPII and UD diagnostic groups.

On measures of frontal executive function, main group effects were found for WCST percentage of perseverative errors (p = 0.01). After Bonferroni correction, UD but not BPII subjects showed significantly increased percentage of perseverative errors compared to controls (p = 0.02) with a medium to large effect size (0.7).

Cognitive correlates – Bipolar II Depressed Subjects

(Table 4) In BPII subjects, TMT-A completion and TMT-B completion both correlated with current anxiety. Current depressive and manic symptoms did not correlate with any cognitive parameters examined.

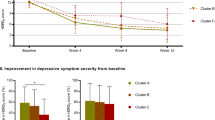

(Figure 1) Illness chronicity (defined as years since first depressive onset) significantly correlated with verbal memory (CAVLT List A total). Lifetime number of hypomanic or depressive episodes did not correlate with any cognitive variables. The correlation of visual memory (immediate recall) with anxiety became insignificant after bootstrapping.

Illness chronicity (defined as years since first depressive onset) significantly correlated with verbal memory (CAVLT List A total). 95% C.I. of Bootstrapped correlation coefficients: 0.03–0.74. CAVLT = Chinese Auditory Verbal Learning Test. (a) Correlation between Illness Chronicity and CAVLT List A Total Correct Response score.(b) Histogram showing bootsttrapped correlation coefficients between Illness chronicity (years since depressive onset) and CAVLT- List A Total Correct Responses.

Cognitive correlates –Unipolar Depressed Subjects

(Table 5) In UD subjects, no correlation was found between cognition and any course variables. Depressive severity did not correlate with TMT-A, TMT-B or any other cognitive variables. The correlation of verbal fluency-correct score was rendered non-significant after bootstrapping.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining cognitive functions of bipolar II and unipolar depressed individuals with no prior psychotropic treatment. Our subjects were young, currently moderately depressed and on average within 3–5 years from first depressive onset, with no history of psychosis or psychoactive substance use.

Our main finding was that treatment-naïve young individuals with BPII had cognitive function distinguished from unipolar depressed individuals by an intact cognitive speed (TMT-A completion). UD patients had more significant impairment in executive function. In particular, cognitive function (verbal memory) correlated with illness chronicity only in bipolar II but not unipolar depression. The findings were interesting in a number of ways.

Firstly, the relatively intact cognitive function in our depressed BPII patients was consistent with those reported by Taylor Tavares et al.14, which compared unmedicated bipolar II with unipolar depressed patients where unipolar patients showed an increased level of cognitive impairment. It is likely that the discrepancy from reports of impaired attention and memory in medicated bipolar II subjects15,16,17 was attributable to the effect of medications, as all studies reporting marked cognitive impairment in Bipolar II involved medicated samples, whereas the unmedicated patients in Taylor Tavares et al. had on average 15–18 years of illness too.

Secondly, that UD subjects had slower cognitive speed (TMT-A completion time) than BPII depressed subjects was consistent with clinical observation that psychomotor retardation tended to characterize UD as opposed to psychomotor activation in BPII depression18. The more prominent impairment of cognitive flexibility in UD instead of BPII compared to healthy controls was also compatible with the findings of Taylor Tavares et al.14, but larger samples may help clarify the trend-level increase observed here.

These may also suggest fundamentally distinct neuroanatomical and functional changes observed in UD and BPII depression. Cognitive processing speed has been attributed to global white matter volume, structural integrity of white matter tracts in bilateral parietal and temporal lobes, along with left middle frontal gyrus, which correspond to the trajectories of the superior and inferior longitudinal fasciculi19,20. While there is a lack of neuroimaging data on treatment-naïve bipolar subjects, an intact neurocognitive performance in BPII contradicted with structural imaging studies which demonstrated increased deep white matter hyperintensities (DMWH) in bipolar I versus unipolar depressed patients, particularly the left superior longitudinal fasciculus21. It is however likely that broader white matter deficits would appear only later in the course of illness as a consequence of energy metabolism disturbances in bipolar disorders22. Prospective investigation of white-matter changes and their correlation with processing speed in bipolar II subjects would be needed to clarify this issue.

Thirdly, our exploratory analysis interestingly showed correlation between disease chronicity and verbal memory (CAVLT List A Total) only in BPII but not UD. The different implications of verbal memory deficit in UD and BPII is compatible with the existing literature. A recent meta-analysis found verbal memory in patients with Major Depressive Disorder to be correlated with current symptoms while attention and executive dysfunction to be compatible with trait deficits23. Previous studies also found verbal memory impairment in Bipolar I and II to be a stable deficit, reflecting illness chronicity and a trait marker for manic episodes3,24,25,26,27. Although we did not observe significant between-group differences in verbal memory, possibly limited by sample size, the chronicity correlation in bipolar II appeared compatible with existing literature in being a phenomenon specific to bipolarity.

There are a few limitations in our study. First, in spite of the difficulty in recruiting untreated bipolar II and unipolar depressed patients of comparable severity, the modest sample size (20 BPII, 35 UD, 35 controls) meant that there was only sufficient power to detect a between-group difference of large effect size = 0.80 or above between the 20 BPII and 35 UD or HC subjects, and in the BPII subjects, there was sufficient power to detect correlations at effect size of at least 0.55. For example, there was insufficient statistical power (0.49) to detect significant difference in TMT-B, of effect size = 0.42 that was found between the BPII and UD subjects. Second, the cross-sectional nature of our study may limit precision of course variables such as age of onset, frequency and duration of past affective episodes, and preclude examination of causality. Prospective longitudinal studies may minimize these biases but the effect of medications would also become difficult to eliminate. Third, we did not include bipolar I depressed individuals in the study which would otherwise even more clearly establish the value of cognitive differences in bipolar/unipolar distinction. Given the difficulty in recruiting individuals with bipolar I disorders in an unmedicated state – as they would more likely stay on or were given mood stabilisers given the disruptive nature of their manic states, such effort should be considered in the context of a multi-centre study. Lastly, given that this study only involved young, unmedicated and currently depressed patients, there remained a likelihood that some of these currently depressed patients with no overt hypomanic features will eventually develop hypomanic episodes. This may have resulted in an underestimate of trait differences between the bipolar and unipolar groups. Inclusion of subjects with longer durations of affective illness would give better assurance of diagnostic stability of the unipolar depressed group identified, while a longitudinal study to follow-up on the cognitive and symptomatic profiles of these patients would allow re-analysing the baseline data in light of updated clinical categorisation upon follow-up, but also help identify baseline predictors for later conversion to bipolarity.

In conclusion, we found young and treatment-naïve patients with BPII depression to be distinguished from unipolar depressed patients by a relatively intact cognitive profile, with a verbal memory-chronicity correlation that suggested a stronger resemblance of BPII to BPI rather than UD. Our data did not provide direct support to the hypothesis of neuro-progression, although the relative proximity of our subjects to illness onset did sensitise our data to trait correlates rather than neuroprogressive consequences. Longitudinal studies of longer follow-up duration on cognition of Bipolar II individuals is warranted to examine for any illness progression effects. The contrast of our findings to those from medicated samples also indicates need for closer examination on the cognitive effects of medications used for treatment of patients with bipolar disorders, irrespective of efficacy on affective symptoms.

Methods

Participants and Recruitment

Given the scarcity of drug-naïve patients, we comprehensively recruited all treatment-naïve, currently depressed patients aged 18 to 35 presenting to a specialist psychiatric clinic in the years 2014–2017. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) age 18 to 35, (ii) currently satisfying the criteria for DSM-IV-TR Major Depressive Episode, (iii) Unipolar depression as defined by meeting DSM-IV-TR criteria for Major Depressive Disorder, with no history of hypomanic episodes, Bipolar II disorder as defined by RDC criteria (DSM-IV-TR major depressive episode with history of hypomanic episodes of at least 2-day duration)28; (iii) and had no prior exposure to any psychotropic drug treatment in their lifetime. All research assessments were made before the first clinic appointment. Diagnostic assessments were conducted by trained interviewers using the Chinese bilingual version of the SCID-I adapted to facilitate diagnosis of current and lifetime hypomanic episodes under the supervision of an experienced clinician academic psychiatrist8,28,29. All lifetime affective episodes were enquired year by year from the first onset of depression using a modified life-chart method based on SCID-I. Repeated interviews with patients and informants were sought to confirm that past hypomanic episodes were observable. Exclusion criteria included current and lifetime histories of psychoses, substance misuse, organic brain syndromes, or evidence of intellectual disability. Healthy volunteers with no personal or family history of any mental disorders were recruited from online advertisements.

Matching of healthy controls with the UD and BPII groups was done on a group level so as to constitute similar age, gender and education in healthy controls compared to the subject groups combined. We were unable to conduct age/gender/education matching between the UD and BPII group owing to the scarcity of treatment-naïve and currently depressed subjects, especially those with BPII, meeting the recruitment criteria.

All eligible participants provided valid written informed consent. All experimental protocols were approved by the New Territories East Cluster- Chinese University of Hong Kong Clinical Research Ethics Committee and all procedures were performed in accordance with the approved guidelines and regulations.

Cognitive and Clinical Assessments

Current-week affective symptoms were evaluated by trained clinician interviewers with the interviewer-administered Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale30, Young Mania Rating Scale31, and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale32. Current health-related quality of life was rated with the Short-form-36 health survey (SF-36)33, a popular generic self-rated measure of health-related quality of life, validated for Chinese settings34. Medication history was confirmed, apart from direct enquiry with the subjects and caregivers with a multi-tiered approach – (i) current and lifetime use, adherence, and dosages of all psychotropics were retrieved from a territory-wide hospital computerized management system (ii) Access to family physician or private practitioners with the subjects’ consent (iii) Pill count.

A battery of neuropsychological tests was used to assess a broad range of cognitive functions:

Attention and mental tracking-

Processing Speed - Trail-making test A35

Attention - Digit Span Forward, Digit Span Backwards36,

Attention switching - Trail-making Test B35

Frontal Executive Function-

Wisconsin Cart Sorting Test37

Verbal fluency – Category fluency Test38

Verbal Memory – Chinese Auditory Verbal Learning Test39

Visual Learning – Wechsler Memory Scale- Visual reproduction40

The Three-subtest Short Form of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III was conducted in all participants to assess general intelligence40,41.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS v24.0 was used for data analysis. The demographic characteristics and diagnostic variables are assessed using Chi-square for categorical variables, unpaired t-test for continuous variables. Scaled neuropsychological test scores, MADRS, HAMA, YMRS and SF-36 scores were compared between groups with one-way ANOVA. Post-hoc Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons was used in between-group pairwise comparisons. Welch’s F statistic was used for comparison of continuous variables where variances were not equal between groups. Pearson’s correlation was used for exploratory analysis of correlation between mood ratings, course variables and neuropsychological test scaled scores on tests that showed at least a small effect-size (Cohen’s d =/> 0.2) compared to healthy controls. Bootstrapping was applied for the correlational analysis to adjust for effect of outliers. A two-sided P-value of less than 0.05 is considered significant. Given its exploratory nature, we did not apply corrections for multiple comparisons in the correlational analyses, but only correlations of p value less than 0.05, and with BCa 95% C.I. not including zero would be considered significant.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Martinez-Aran, A. et al. Cognitive function across manic or hypomanic, depressed, and euthymic states in bipolar disorder. The American journal of psychiatry 161, 262–270 (2004).

Martino, D. J. et al. Relationship between neurocognitive functioning and episode recurrences in bipolar disorder. Journal of affective disorders, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.037 (2012).

Robinson, L. J. & Ferrier, I. N. Evolution of cognitive impairment in bipolar disorder: a systematic review of cross-sectional evidence. Bipolar Disord 8, 103–116, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00277.x (2006).

Torres, I. J., Boudreau, V. G. & Yatham, L. N. Neuropsychological functioning in euthymic bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum, 17–26, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01055.x (2007).

Post, R. M., Fleming, J. & Kapczinski, F. Neurobiological correlates of illness progression in the recurrent affective disorders. Journal of psychiatric research 46, 561–573, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.02.004 (2012).

Balanzá-Martínez, V. et al. Neurocognition in bipolar disorders—A closer look at comorbidities and medications. European Journal of Pharmacology 626, 87–96, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.10.018 (2010).

Judd, L. L. et al. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Archives of general psychiatry 60, 261–269 (2003).

Mak, A. D. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar II disorder in major depressive patients at a psychiatric outpatient clinic in Hong Kong. Journal of affective disorders 112, 201–205, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.05.006 (2009).

Akiskal, H. S. et al. Switching from ‘unipolar’ to bipolar II. An 11-year prospective study of clinical and temperamental predictors in 559 patients. Archives of general psychiatry 52, 114–123 (1995).

Goldberg, J. F., Harrow, M. & Whiteside, J. E. Risk for bipolar illness in patients initially hospitalized for unipolar depression. The American journal of psychiatry 158, 1265–1270, https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1265 (2001).

Phillips, M. L. & Kupfer, D. J. Bipolar disorder diagnosis: challenges and future directions. Lancet (London, England) 381, 1663–1671, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60989-7 (2013).

Holmes, M. K. et al. A comparison of cognitive functioning in medicated and unmedicated subjects with bipolar depression. Bipolar Disorders 10, 806–815, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00628.x (2008).

Andersson, S., Barder, H. E., Hellvin, T., Løvdahl, H. & Malt, U. F. Neuropsychological and electrophysiological indices of neurocognitive dysfunction in bipolar II disorder. Bipolar Disorders 10, 888–899, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00638.x (2008).

Taylor Tavares, J. V. et al. Distinct profiles of neurocognitive function in unmedicated unipolar depression and bipolar II depression. Biological psychiatry 62, 917–924, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.034 (2007).

Savitz, J. B., van der Merwe, L., Stein, D. J., Solms, M. & Ramesar, R. S. Neuropsychological task performance in bipolar spectrum illness: genetics, alcohol abuse, medication and childhood trauma. Bipolar Disord 10, 479–494, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00591.x (2008).

Sole, B. et al. Are bipolar II patients cognitively impaired? A systematic review. Psychological medicine 41, 1791–1803, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711000018 (2011).

Xu, G. et al. Neuropsychological performance in bipolar I, bipolar II and unipolar depression patients: a longitudinal, naturalistic study. Journal of affective disorders 136, 328–339, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.11.029 (2012).

Withall, A., Harris, L. M. & Cumming, S. R. A longitudinal study of cognitive function in melancholic and non-melancholic subtypes of major depressive disorder. Journal of affective disorders 123, 150–157, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.07.012 (2010).

Magistro, D. et al. The Relationship between Processing Speed and Regional White Matter Volume in Healthy Young People. PLoS One 10, e0136386, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136386 (2015).

Turken, A. et al. Cognitive processing speed and the structure of white matter pathways: convergent evidence from normal variation and lesion studies. Neuroimage 42, 1032–1044, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.057 (2008).

Versace, A. et al. Right orbitofrontal corticolimbic and left corticocortical white matter connectivity differentiate bipolar and unipolar depression. Biological psychiatry 68, 560–567, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.036 (2010).

Versace, A. et al. Elevated serum measures of lipid peroxidation and abnormal prefrontal white matter in euthymic bipolar adults: toward peripheral biomarkers of bipolar disorder. Molecular psychiatry 19, 200–208, https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2012.188 (2014).

Lee, R. S., Hermens, D. F., Porter, M. A. & Redoblado-Hodge, M. A. A meta-analysis of cognitive deficits in first-episode Major Depressive Disorder. Journal of affective disorders 140, 113–124, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.10.023 (2012).

Braw, Y. et al. A longitudinal study of cognition in asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic bipolar disorder patients. Psychiatry Res 210, 842–849, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.01.003 (2013).

Mora, E., Portella, M. J., Forcada, I., Vieta, E. & Mur, M. Persistence of cognitive impairment and its negative impact on psychosocial functioning in lithium-treated, euthymic bipolar patients: a 6-year follow-up study. Psychological medicine 43, 1187–1196, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712001948 (2013).

Schouws, S. N., Stek, M. L., Comijs, H. C., Dols, A. & Beekman, A. T. Cognitive decline in elderly bipolar disorder patients: a follow-up study. Bipolar Disord 14, 749–755, https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12000 (2012).

Torrent, C. et al. Cognitive impairment in bipolar II disorder. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science 189, 254–259, https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.105.017269 (2006).

Benazzi, F. & Akiskal, H. S. Refining the evaluation of bipolar II: beyond the strict SCID-CV guidelines for hypomania. Journal of affective disorders 73, 33–38 (2003).

So, E. et al. The Chinese- bilingual SCID-I/P Project: stage 1 — reliability for mood disorders and schizophrenia. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 13, 7–18 (2003).

Montgomery, S. A. & Asberg, M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science 134, 382–389 (1979).

Young, R. C., Biggs, J. T., Ziegler, V. E. & Meyer, D. A. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science 133, 429–435 (1978).

Hamilton, M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. The British journal of medical psychology 32, 50–55 (1959).

Brazier, J. E. et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. Bmj 305, 160–164 (1992).

Lam, C. L., Tse, E. Y., Gandek, B. & Fong, D. Y. The SF-36 summary scales were valid, reliable, and equivalent in a Chinese population. Journal of clinical epidemiology 58, 815–822, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.12.008 (2005).

Reitan, R. M. Validity of trail making test as an indication of organic brain disease. Percept Mot Skills 8, 271–276 (1958).

Wechsler, D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Revised. (Psychological Corporation, 1981).

Heaton, R. K. Wisconsin cart sorting test manual. (Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc, 1981, 1981).

Chan, A. S. & Poon, M. W. Performance of 7- to 95-year-old individuals in a Chinese version of the category fluency test. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 5, 525–533, https://doi.org/10.1017/S135561779956606X (1999).

Lee, T., Yuen, K. & Chan, C. Normative data for neuropsychological measures of fluency, attention, and memory measures for Hong Kong Chinese. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology 24, 615–632, https://doi.org/10.1076/jcen.24.5.615.1001 (2002).

Wechsler, D. Wechsler memory scale-revised manual. (Psychological Corporation, 1987).

Chan, E. L. S., Chen, E. Y. H. & Chan, R. C. K. Three-subtest Short Form of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III for Patients with Psychotic Disorders: a Preliminary Report. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 15, 39–42 (2005).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Miss Marina Wong, Novelle Poon, Priscilla Wong, Ivy Lam for assistance in data management.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Arthur D.P. Mak – study concept and design, supervision and coordination of data collection, study supervision, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, Domily Lau- data analysis and results reporting. Suzanne H.W. So – coordination and supervision of data collection and assessment. Alicia K.W. Chan – data collection and assessment. Owen Leung – database management. Sheila L.Y. Wong – graphics and analysis. Linda Lam – support and monitoring of study logistics. C.M. Leung – hypothesis generation, critical revision of manuscript. Sing Lee - critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mak, A.D.P., Lau, D.T.Y., Chan, A.K.W. et al. Cognitive Impairment In Treatment-Naïve Bipolar II and Unipolar Depression. Sci Rep 8, 1905 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20295-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20295-3

This article is cited by

-

Neurocognitive deficits in depression: a systematic review of cognitive impairment in the acute and remitted state

European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience (2023)

-

White matter integrity in young medication-naïve bipolar II depressed adults

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Functional connectivity between the thalamus and the primary somatosensory cortex in major depressive disorder: a resting-state fMRI study

BMC Psychiatry (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.