Abstract

Polygenic risk scores (PRSs) aggregate the many small effects of alleles across the human genome to estimate the risk of a disease or disease-related trait for an individual. The potential benefits of PRSs include cost-effective enhancement of primary disease prevention, more refined diagnoses and improved precision when prescribing medicines. However, these must be weighed against the potential risks, such as uncertainties and biases in PRS performance, as well as potential misunderstanding and misuse of these within medical practice and in wider society. By addressing key issues including gaps in best practices, risk communication and regulatory frameworks, PRSs can be used responsibly to improve human health. Here, the International Common Disease Alliance’s PRS Task Force, a multidisciplinary group comprising expertise in genetics, law, ethics, behavioral science and more, highlights recent research to provide a comprehensive summary of the state of polygenic score research, as well as the needs and challenges as PRSs move closer to widespread use in the clinic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

PRSs provide an estimate of an individual’s germline genetic risk for a specific disease or trait, and recent studies have shown that they may have clinical utility in a variety of settings. Although not diagnostic per se, PRSs generally provide information that can be used to enhance or guide, but not replace, risk prediction models and diagnostic pathways. In essence, apart from being based on an individual’s germline genome, a PRS may be treated as any other risk predictor. Because of recent advances in PRS research, it is timely to consider how to appropriately and responsibly use these scores in the clinic and in society.

The International Common Disease Alliance (ICDA) aims to improve prevention, diagnosis and treatment of common diseases across the world, in part through understanding how genetics can be leveraged to improve health. There is a spectrum of potential benefits that the use of PRSs could have in research, clinical care, clinical-trial design and public health. There are also known risks and limitations of PRSs, and gaps in knowledge related to their use, highlighting the need for additional research and debate to ensure responsible use. To this end, the ICDA has established the PRS Task Force, which has initially focused on the potential use of PRSs in clinical care and population health while also recognizing their potential utility to enhance efficacy of clinical trials.

The PRS Task Force interprets ‘responsible use’ as use of a PRS where there are clear benefits that outweigh risks, and where effort is taken towards a goal of equitable benefit for all. The potential benefits and risks remain incompletely quantified at present but will vary by clinical context, healthcare system, and population. Ideally, all people have equal opportunity to benefit from PRSs, and it is important that researchers and healthcare professionals (HCPs) are supported to enable this. Equitable opportunity is not just about known issues for PRS development, for example differences in PRS performance for individuals of different ancestries, but also the real-world impact PRSs will ultimately have and on whom.

In working toward responsible use, a prerequisite is to understand the gaps in knowledge that prevent responsible use, as well as potential risks and benefits. Academic discourse can initiate the gathering of new evidence or development of best practices, which are needed to ensure responsible use. In this Perspective, we therefore outline the Task Force’s understanding of the current state of knowledge regarding benefits, risks and gaps regarding PRS, and provide an overview of key objectives (Table 1) in order to maximize responsible use of PRS in clinical settings.

Benefits

PRSs have the potential to enhance disease risk prediction1 and diagnostic refinement; predict progression and recurrence of disease; deploy precision therapeutics; and improve the efficiency of population-level screening. Furthermore, a single genetic test per individual (US$35 for a genome-wide array with automated bioinformatics) provides raw genetic information that could be used to generate many PRSs (for example for heart disease, diabetes, or breast cancer) based on approaches that exist now, or that could be developed in the future from existing genetic data.

Disease risk prediction

PRSs are constructed on the basis of inherited genetic variation, which is set at conception, and can therefore be utilized earlier in life than can many lifestyle, age-related, and other non-genetic risk factors. PRSs provide the opportunity to estimate risk trajectories across a lifetime, rather than for 5 or 10 years, as is the case for most clinical risk scores. Importantly, PRSs often capture risk that is substantially independent of and thus complementary to traditional risk factors and clinical risk scores. Furthermore, elevated genetic risk can be associated with earlier onset of disease, even in the absence of traditional risk factors. Thus, PRSs hold the potential to improve the accuracy of both early and targeted primary prevention, particularly for chronic diseases that develop over decades.

Multiple studies of coronary artery disease (CAD) show that disease-prediction algorithms that jointly model the effects of clinical risk factors and PRSs perform better than do those that consider only clinical risk factors2,3,4,5,6. Thus, adding CAD PRSs to existing screening protocols and prevention strategies may more accurately identify individuals at high risk of developing disease. Particularly for cardiovascular disease, PRSs facilitate lifetime risk prediction beyond current models that predict the 5- to 10-year risk, which are typically optimized for middle-aged individuals.

There is also growing evidence that PRSs substantially improve disease risk estimates in people who carry high-impact disease-causing genetic variants (for example, for familial hypercholesterolemia (FH)7 or breast cancer8). As such, an elevated polygenic risk score may augment the risk conferred by a high-impact mutation, or a protective polygenic risk score may compensate for the pathogenic mutation and bring the individual’s risk closer to the population average7. However, it should be noted that providing PRSs based on common variants, but not considering or testing for rare high-impact variants, may give a substantially incomplete risk estimate for individuals, especially those with a family history (of breast cancer, for example).

While most evidence suggests clinical utility may be maximal when PRSs are combined with non-genetic risk factors, there is also evidence that PRSs alone may have utility for those with extremely high polygenic scores. For example, persons in the top 8% of a CAD PRS distribution have a risk comparable to that of those with a monogenic familial hypercholesterolemia mutation6, whereas women in the top 10% of a distribution of breast cancer PRSs have a 30% lifetime risk of breast cancer, comparable to the risk of those with pathogenic mutations in the CHEK2 and ATM genes8. On the basis of equivalent risk principles, it can be argued that an individual with a PRS-based risk that is similar to a monogenic risk should qualify for a similar level of preventative therapies.

The clinical benefit of utilizing PRSs for disease risk prediction also depends on the availability of preventive interventions and/or medicines. For example, while CAD PRS improves risk stratification for future cardiovascular disease, individuals with high clinical risk factors and an elevated CAD PRS may derive more benefit (an increased reduction in risk) from statin treatment than would individuals at low polygenic risk9,10. On the basis of cross-sectional studies, a favorable lifestyle appears to compensate for the increased risk of a high CAD PRS11. Given that the practical implications for disease prevention will be disease specific, it is clear that further studies are warranted to elucidate the proper mode of prevention for each disease and any relevant subgroups.

Diagnostic refinement

PRSs may improve diagnosis accuracy. For example, clinical differentiation between type 1 and type 2 diabetes (T1D and T2D, respectively) can be complex because the presenting symptoms are similar and laboratory results often overlap. Diagnostic accuracy is currently imperfect; improved diagnosis can influence treatment plans (for example, whether insulin is prescribed) and improve outcomes (for example, reduced risk of diabetic ketoacidosis)12. Further, recent evidence suggests that approximately 40% of individuals who develop T1D during their lifetime present with symptoms after the age of 30 years13. A PRS for differentiating T1D and T2D achieved reasonably high predictive capacity — while not a metric of clinical utility, the area under the receiver operator curve (AUROC; a composite of sensitivity and specificity with maximum value of 1.0) was 0.88. When integrated with other clinical risk factors, the resulting model achieved an improved AUROC of 0.96 (ref. 14). T1D PRSs have shown further promise in prioritizing newborns for autoantibody screening15 and as part of integrated models to predict disease prior to symptom onset, which may help prevent T1D and complications throughout early childhood16.

Diagnostic refinements using PRSs have also been evaluated for other autoimmune diseases. A celiac disease PRS improves upon HLA typing alone17,18,19, and pilot clinical studies indicate improved effectiveness and cost-efficiency for celiac diagnosis, potentially reducing invasive diagnostic procedures20. For juvenile idiopathic arthritis and its subtypes, PRS may substantially improve upon clinical diagnosis, potentially reducing long waiting periods for diagnosis and treatment21. Furthermore, a PRS for ankylosing spondylitis has been shown to have high diagnostic capacity (AUROCs of 0.92 and 0.94 in European and East Asian ancestries, respectively) and potential clinical utility for earlier and cost-effective diagnosis if combined with magnetic resonance imaging22.

Slowing disease progression and recurrence

Recent studies have assessed the potential clinical utility of PRSs for slowing disease progression and recurrence, and reducing the need for deployment of new (sometimes costly) therapeutics. Among those with acute coronary syndrome and elevated lipids who were treated with optimized statin treatment, a high CAD PRS was associated with elevated risk for recurrent cardiovascular events as well as larger absolute and relative risk reduction with recently developed PCSK9 inhibitors23,24. Similarly, a high T2D PRS has been associated with earlier disease onset, increased risk of progression to an insulin-dependent stage, and a low response to glucose-lowering drugs25. PRS screening could identify individuals at a preclinical stage of T2D to allow earlier control of glycemia and identify personalized treatments. This could motivate a regime of diet and exercise to potentially avoid pharmacologic interventions to manage T2D26.

Prompting risk-reducing behaviors

PRS information could motivate risk-reducing health behavior, for example by prompting initiation of medication, screening, or lifestyle changes27. Although not focused on PRSs specifically, research on inherited cancer syndromes has shown improved screening adherence following disclosure of genetic test results28. Additionally, a recent study suggested that providing people with personal genetic results about obesity risk can alter cardiorespiratory and satiety physiologies, including perceived exertion and running endurance during exercise and perceived fullness after food consumption29.

There is still limited data on whether disclosure of PRS information motivates health behavior changes across a spectrum of common diseases, but emerging evidence suggests a potentially beneficial behavioral impact for CAD risk. Studies of disclosure of CAD PRSs found increased perception of personal control and increased information seeking30, favorable health behaviors31, and increased shared decision-making resulting in more statin prescriptions32. Nonetheless, given that multiple factors besides the disclosure of genetic risk can impact health behaviors29, future disease risk communication strategies should carefully consider the relative and combined effects of all relevant types of information.

Improving population screening

The purpose of population-level screening is to identify individuals at sufficiently elevated risk of disease that they would benefit from intervention. However, a key barrier to population-level screening is that the pretest probability of any single individual in the population having the disease is low, and the number of false positives resulting from screening can be very high. In addition, the vast majority of individuals completing population-level screening are told that their risk of disease is too low to warrant an intervention; thus, most expenditures in screening programs lead to no change in clinical care.

Despite these in-built inefficiencies, population-level screening could be improved in several ways using PRSs. For example, PRSs may improve the identification of individuals who would benefit from inclusion in screening intervention programs, the timing of screening initiation, the frequency of screening, and/or the tools (for example, non-genetic clinical risk scores) used as part of screening. We provide three examples of screening strategies utilizing PRS.

While osteoporosis screening has rarely been implemented at the population level, recent trials have demonstrated a reduction in hip fracture rates by screening for older women at risk, predominantly using assessments of bone mineral density. However, most women are deemed to be at insufficient risk to merit intervention after screening. By applying a PRS to screen individuals at risk for low bone density (the main metric for therapeutic interventions), the number of people requiring bone density evaluations may be reduced by ~40%, with high sensitivity (~93%) and specificity (~98%) to identify those requiring clinical care33.

For breast cancer, PRSs can be used to more accurately quantify 10-year risk. For women aged 40–50 years with an unknown family history of disease, the average population risk of breast cancer is 1.7%. Using questionnaire-based risk factors and mammographic density, the BOADICEA risk prediction algorithm identifies 9.2% of the women in the population who would be classified at moderate or high risk of developing breast cancer (based on the UK’s National Institutes of Clinical and Healthcare Excellence (NICE) guidelines34). A breast cancer PRS alone identifies 10%. As such, a PRS for breast cancer risk could be used to optimize screening initiation and the frequency of mammograms. An integrated model with PRS, questionnaire-based risk factors, and mammographic density identifies 13% of women with a moderate or high risk. BOADICEA v5 (as implemented in the CanRisk tool) already implements a 313-variant PRS and currently supports hundreds of thousands of women, doctors, and genetic counselors annually in >90 countries making treatment decisions34,35. PRS-guided mammographic screening is also being tested in the WISDOM and PERSPECTIVE I&I studies36,37.

The benefits of a CAD PRS could be sufficient to justify an update to population-level screening. By adding PRSs to existing risk prediction models, multiple large studies have shown improved individual risk reclassification across a population, and thus may improve targeted therapeutic interventions (for example, statins3,38). PRS-guided, lipid-lowering treatment, particularly for those at intermediate risk, has shown promise in decreasing cardiovascular disease events2,39,40. With a safe, effective and inexpensive preventative therapeutic, screening strategies for cardiovascular disease that consider PRS and conventional risk factors jointly (for example in a primary care population of at least 40 years of age39) or that take a 2-stage approach (screening first with PRS then with conventional risk factors, or vice versa40,41) appear to robustly provide clinical benefit; however, further refinement regarding whom and when to treat is still necessary.

Risks

Despite the potential, and in some cases demonstrated, benefits of PRS there are potential risks to both individual patients and the general population from clinical use of PRSs, which should be acknowledged and mitigated42.

Risks arising from ‘incorrect’ information

If a PRS is used as a standalone tool, a key risk relates to delivering substantially incorrect risk estimates to the individual. ‘False positive’ results (for example, wrongly categorizing an individual as ‘high risk’ on the basis of their PRS) could lead to inappropriate clinical actions and unnecessary emotional harm. The clinical implications of a substantially incorrect polygenic score are dependent on disease severity, the relative contribution of non-genetic risk factors, and the cost or harm of recommended or missed interventions42,43,44. It is important to emphasize to individuals that PRSs are estimates with a level of uncertainty around them that could affect risk stratification owing to statistical imprecision45 and the use of discrete cut-offs46. Notably, these concerns regarding incorrect or imprecise risk estimates are the same for all risk factors and are not specific to PRS.

PRSs are also susceptible to the same biases as other prediction models in that their performance (whether classification accuracy or short-term or long-term prediction) can be substantially attenuated if the individual is not adequately represented by the original study population. A major source of error for individuals of non-European ancestries is the lack of representation in genotyped cohort studies. As with many areas of medical research, the majority of genetic research has been conducted in people of European ancestry (~88% of participants in published GWAS47,48 to date), which often leads to reduced predictive performance for PRS in individuals from other ancestries49,50,51. PRS performance can vary widely in admixed individuals49, or for other demographic groups by age and sex52. These differences could in turn exacerbate existing demographic disparities in access to healthcare and clinical outcomes53.

Inequities in performance of biomarkers and interventions across demographic characteristics are pervasive in medicine. Examples include glomerular filtration rate estimation across ethnicities and interventions for chronic kidney disease (such as renal transplantation); risk prediction for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and adverse side effects of statins in Black patients; and body mass index thresholds and risk of diabetes in Asian individuals54,55. While some tolerance of differential performance is necessary, how much should be tolerated is an important question which must consider a wide range of issues, including specific clinical context, healthcare system and economics, as well as ethics and the ramifications of withholding or modifying the performance/treatment.

Risks arising from ‘correct’ information

Risks remain for PRS based on ‘correct’ information — that which is informative, well-calibrated, and minimally biased. These risks are primarily related to the communication of the PRS information to the individual, and require careful consideration as they may be incorrectly conflated with return of monogenic results, which are more diagnostic in nature. Risks include failure to convey the uncertainty in the estimate, and to deliver timely counsel regarding approaches to reduce overall risk (not just that attributable to the PRS). Improper risk communication may result in physical or financial harm from unnecessary lifestyle or clinical interventions, as well as unwarranted negative psychosocial effects such as anxiety or depression56.

In the United States, the current standard for ethical return of monogenic results requires healthcare professionals trained in genetics (for example, genetic counselors), typically working together with a physician who is an expert in preventing, screening for, or treating the disease under discussion. This approach typically involves genetic counseling before and after the genetic test, followed by a physician visit. For population-level screening, it is not feasible to scale this process for the return of PRS results to many individuals for many diseases, particularly because genetic counselors are in short supply in many countries57,58. However, there are existing models for successful large-scale return of genomic results in the primary care setting59, even when those HCPs report average levels of genetics training and comfort with genetic information60.

Communication of PRS results to patients or their primary care physicians are being trialed using a wide variety of formats, including indicating the individual’s position on a bell curve, their percentile, and categorical risks (for example ‘slightly increased risk’). For individuals from diverse ancestries and cultures, researchers are only just beginning to investigate which display formats optimize comprehension of PRSs45.

The majority of studies to date have found little evidence of lasting negative psychosocial effects of providing monogenic results to individuals who choose to receive them61. However, a few studies have found negative effects; in one, informing participants of the APOE genotype for risk of Alzheimer’s disease impacted their objective and subjective performance on subsequent memory tests62. Although there is a relatively large body of literature on the psychosocial effects of returning monogenic results to patients and families in clinical settings, the research assessing the impact of PRSs on individuals is still in the very early stages. This is understandable given the relatively nascent stage of PRS discovery research compared with research into rare high-penetrance variants, but it is vital that these translational studies are now conducted given the potentially widespread use of PRSs in the near future. At present, little is known about the potential harms of PRSs, such as anxiety, stress, or misunderstanding, and about how these harms can be best avoided via careful communication and delivery of the results and appropriate support before and after.

Mitigating societal risks

PRSs are becoming more widely available for a broad range of common conditions, which strengthens the case for stronger protections against genetic discrimination. History has shown that marginalized groups are especially vulnerable to both racism and genetic discrimination, as exemplified by mandatory sickle-cell screening in the United States in the 1970s63,64. In that case, discriminatory practices denied education opportunities, employment, and insurance on the basis of carrier status — which primarily affected individuals of African ancestries64. This and other historical injustices have been reported as causes of hesitancy in undergoing predictive genetic testing for African Americans65. Failure to strengthen and enforce antidiscrimination regulations is particularly pertinent as we seek to increase research participation from underrepresented groups63,66, who may be suspicious of medical research or healthcare more generally67.

Without appropriate communication of the uncertainty around PRS estimates, large-scale deployment of PRSs could potentially reinforce and amplify false genetic-determinism attitudes. If healthcare professionals adopt these attitudes, it may influence what type of care will be offered to whom. Widespread and irresponsible use of PRS risks may systematically downplay the role of the environment in an individual’s health. Not only would this be inaccurate, but it could potentially offset the work that has been done to highlight social determinants of health and work against interventions that help eliminate health disparities68. Ultimately, best practices for PRS delivery will need to be done in close consultation with behavioral and social scientists so that both the social and genetic determinants of health, and their respective interventions, are considered.

Human genetic information, and the language of geneticists themselves, can be easily misunderstood by the public and cause harm69. A particularly concerning risk for minority groups is the comparison of PRS distributions between populations (including ancestries). Any difference in mean value of a PRS between populations could be used in a potentially racist or sexist attempt to explain observed group differences in health outcomes, behaviors, wealth and other traits. Such inferences would be both harmful and incorrect because differences in mean PRS value between populations are typically due to allele-frequency differences and biases in the genetic discovery data, and thus unrelated to differences in phenotype70.

The availability and ease of developing PRS may also lead to inappropriate use. For example, some companies are offering PRSs for embryo selection of nonclinical traits under the rationale that PRSs are used in medicine71. However, the clinical value of using PRSs for embryo selection is likely to be limited71, and the ethics of parents selecting nonclinical traits or incompletely understood clinical traits in offspring is ethically dubious72.

Direct-to-consumer companies make genetic tests available to anyone who submits a sample, and they may also return PRS results for a wider variety of diseases and phenotypes. The mode of communication may be via email or web portal, and may have only limited or no capacity to offer genetic counseling. Traits that are behavioral or have a stigma attached may be particularly distressing to the consumer73. For preventable diseases, follow-up with a physician may be less likely to happen than when results are returned in a clinical setting. For diseases with no available intervention, the potential for psychosocial stress or harm must be considered, and the potential benefits (family planning or altered life goals) weighted against the stresses of receiving the result.

Gaps

Deployment of PRS holds both promises and risks, which may improve or detract from patient and population health. However, even for diseases with a large potential benefit and minimal risk of clinical PRS application, consistent and equitable implementation must remain a priority. Prior to large-scale deployment, there are gaps in PRS research that need to be filled for there to be confidence that PRSs will be used responsibly.

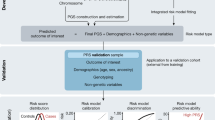

Polygenic risk score development and evaluation

PRS development typically involves selecting a set of genetic variants and corresponding weights, then testing the constructed PRS performance in an independent dataset. Reporting of PRSs and their resultant performance in external datasets has been historically lacking and inconsistent74. Data sharing is critical to PRS development, in particular full genome-wide association study (GWAS) summary statistics that underpin the selection and weighting of genetic variants for a particular trait. Comprehensive databases of GWAS summary statistics, such as the pioneering NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog75, are widely utilized by the community but still only a minority of published GWAS share their full summary statistics76. This is a critical gap that hampers the development, robustness, and generalizability of PRSs. The GWAS research community, global biobank collaborations, and private direct-to-consumer companies should require public sharing of summary statistics, and utilize standardized formats, to avoid exacerbating global health disparities66.

As noted above, some PRSs have reduced performance in people of non-European ancestries, which may exacerbate health inequities66,77. Patients of non-European ancestries with breast cancer are offered less genetic testing, and breast cancer PRSs are frequently relevant for women of European ancestry only78. The historic focus of cohort studies, and medical research more broadly, on people of European ancestry is a key factor in this bias, and the lack of study recruitment of people of non-European ancestries together with that of corresponding genomic and health data is a critical gap. For GWASs and thus PRSs to represent people of non-European ancestries66, we must prioritize resources for recruitment of and data generation for individuals of African, Asian, Indigenous, and other underrepresented ancestries in both wealthy and low-middle-income countries. So far, there are positive signs that human genetics and polygenic score research in particular are working to address ancestry biases, including large-scale diverse cohort recruitment and sharing of ancestry-specific GWAS summary statistics. We hope these continue and intensify to the point where PRSs are a model for other epidemiological and medical research areas where ethnic and ancestral diversity still lags.

Beyond current ancestry biases, there remain gaps in study design and analysis for PRSs. Cryptic substructure within a population or within an ancestry group, potentially related to geography or participation bias, may induce inaccuracies in PRS79,80. If these differences are related to confounders, such as differences in social environment or gene–environment interactions, then care is needed to ensure PRS performance estimates are accurate and fit to inform clinical practice. Multi-morbidity structures and correlations among PRSs also should be considered. Methods to determine PRSs vary in multiple ways; there is a need for clarity on the optimal number of variants to use, how to utilize ancestry information81, how to incorporate high-impact rare variants82, and reliable metrics for selecting the best-performing PRS. Recent analyses have shown that improved imputation reference panels, fine-mapping procedures, and GWASs that include even a small number of participants of of non-European ancestries can ameliorate differential PRS performance83,84. The centralization of well-documented PRS studies, as well as free and open provision of PRS models (genetic variants and weights), for example via the Polygenic Score Catalog85, are also vital. Further improvements will enable comprehensive PRS performance comparisons and will increase the transparency and reproducibility of and public trust in PRS.

Gaps in translation

Although there is largely a consensus that PRS should be used alongside other informative non-genetic risk factors, gaps remain in determining precisely how this should be done. Even once comprehensive models are constructed (whether joint or two-stage), it is not yet clear how best to communicate individual PRSs from laboratories and bioinformatics teams to HCPs, patients and research participants, although work towards this is ongoing by eMERGE Network investigators86, Our Future Health87, and many others. There are particular gaps in best practices regarding results reports for patients. Notably, there is wide diversity and no standards or agreement for clinical reports that include PRSs88.

There are gaps regarding how HCPs interpret and adjust clinical decisions with additional PRS information. There is some evidence to suggest that the use of PRS influence HCPs’ behavior in terms of clinical recommendations and prescribing, but this is largely limited to a handful of disease areas, most notably cardiovascular disease89. Very few clinical guidelines support HCPs in helping patients make informed choices or shared decisions about their healthcare on the basis of PRS results. For example, in England, HCPs have clear guidelines provided by NICE on strategies for patients with cardiovascular disease risk greater than the 10-year risk threshold of 10%90 (or 7.5% in the United States). However, what should the HCP recommend if a patient has high risk on the basis of a PRS alone? What are the potential risks of stigmatization or discrimination, particularly if early in life? What are the implications of parents having this information for their children early in life (prior to the child giving informed consent)? Additionally, effective counseling should take into account cultural beliefs91 and other social factors (for example, access to risk-reducing interventions). Training programs for genetic counselors and HCPs may need to be adapted to appropriately cover PRS-derived risk estimates for common diseases.

Finally, it is unclear whether the use of PRS in specific healthcare systems will be cost-effective if the benefits outweigh the risks. Although the technology needed to generate PRSs (genome-wide genotyping array) is relatively inexpensive, other costs associated with deployment of PRS at scale (for example, genetic counseling time, or training and educational resources for other HCPs) may not be. Early intervention and corresponding healthcare cost reductions are especially important in resource-challenged settings around the world. Addressing this translational gap is a priority that will require studies that consider both economic factors and healthcare management that vary across clinical settings and regions.

Regulation of polygenic risk scores

PRSs need a process for demonstrating and refining clinical utility; preferably, this would be dynamic, adaptive, and mainly focused on using real-world data. An ideal regulatory approach would allow for PRSs to be updated as the science evolves.

Existing regulatory frameworks ensure medical devices that are brought to market are safe and effective by evaluating their quality, effectiveness, accuracy, and safety; the same must be done for PRS. The timelines, costs, supporting documentation, and rigor under which medical devices are evaluated depend on the assigned risk class92, yet the rapid pace of software tool development (which may encompass PRSs) makes it difficult to determine regulatory needs, timing, and terms93. Current regulations recognize that software used for ‘medical purposes’ can, if certain conditions are met, be deemed and regulated as Software as a Medical Device (SaMD), for example those used for diagnosis, treatment, or prevention of disease94,95. In some jurisdictions, risk prediction models and PRSs have expanded the definition of medical purposes to also include prediction, monitoring, and screening96.

With PRS research rapidly iterating between basic and clinical, and subsequent clinical validity and utility constantly evolving, the scientific and technical limitations complicate their current definition within the regulatory frameworks44. Likewise, the use of PRSs for medical purposes is currently uncertain under most legislation44.

This uncertainty is exacerbated because, despite increasing efforts97, medical device regulatory frameworks are not internationally harmonized. The regulatory processes (requirements, costs, timelines, risk classes) as well as their applicability to the specific device vary across jurisdictions. The International Medical Device Regulators Forum SaMD guidelines provide inclusion and exclusion criteria and examine the significance of the information provided by the software for health decisions as well as the seriousness of the healthcare condition for which the software is intended96,98,99,100,101. Yet, there is significant variation in definitions and examples provided in guidelines. Although legal classifications are not settled, Canada102, for example, seems to exclude PRSs from the definition of a medical device; however, the United States could consider them as falling outside the technical definition of clinical-decision support tools and oversee them as medical devices. The European Union SaMD guidelines, on the other hand, focus on the specific intended uses, examples of software excluded from regulation, and whether it is standalone software or an accessory to an in vitro medical device. In the EU, PRSs could be an accessory SaMD depending on the accuracy with which they can predict the risk of developing a medical condition. In fact, the BOADICEA risk prediction model itself, which incorporates the use of a PRS, carries a CE (Conformitè Europëenne) marking as a medical device in the EU103. Where PRSs are not regulated as a SaMD, they would be considered non-device clinical decision support tools. Manufacturers in this case are not obligated to comply with any of the medical device regulations but are encouraged to follow best practices of validation and quality assurance. Efforts are also needed in other regions of the world outside of the EU and North America regarding regulations to anticipate future implementation of PRS in a globally equitable way.

The costs of complying with medical device regulations are likely an important but unknown factor for implementation, access, or use of PRS. These costs will be higher than those associated with following best practices, and high costs may create inequitable access between populations, countries, and subgroups within countries. Furthermore, improving the clinical utility and validity of PRS greatly depends on global collaboration. Burdensome or uncertain regulations can hinder this collaboration by discouraging, complicating, or increasing the costs37. Hence, it is crucial to address regulatory uncertainty and strike a balance between ensuring safety, improving health, and equitable use.

Conclusions

When estimating clinical risk, HCPs typically consider age, sex, ethnicity/ancestry, past medical history, family history, and biomarkers. Incorporating genomic risk information, which can be generated for hundreds of diseases with one DNA test, would mean these risk estimates could be more personalized, more accurate, and utilized earlier in life. Although many risk reduction strategies (for example, healthy diet, exercise, reduced consumption of alcohol and tobacco) are most effective when applied to the whole population, some strategies are not suitable for population-level intervention owing to factors like financial cost and adverse treatment effects. Some strategies (for example, statin use) should be prioritized for high-risk individuals for preventive interventions to effectively balance risk, benefit, and cost. Furthermore, genetically informed clinical tools can enhance diagnosis of subtypes of disease, predict progression and recurrence, and potentially guide treatment regimes. Early results suggest that genetic risk information may prompt patients to make behavioral changes to reduce their disease risk.

There are also risks of PRS deployment that should be considered. Patients or physicians may misunderstand the uncertainty in a PRS-informed risk estimate. Individuals with non-European ancestry may have inaccurate risk estimates due to a relative lack of large prospective cohorts with genomic data from these ancestries, potentially exacerbating inequities in healthcare. We advocate for effective and clear risk communication by trained professionals to minimize potential psychosocial effects.

As noted above, a current example of a PRS in clinical use is the 313-variant PRS for breast cancer104 implemented as part of the multifactorial BOADICEA/CanRisk tool34, which itself carries CE marking for use in the European Economic Area. BOADICEA/CanRisk is part of a first wave of PRSs moving into clinical practice, and it signifies the urgency of the clinical and research communities to develop responsible use frameworks more broadly across many clinical pathways.

Although many inequities in access to healthcare are evident across nations as well as demographic and socioeconomic groups, PRSs do also have the potential to improve equitable access to preventive care, hopefully serving as a model which aligns with and stimulates other equity initiatives in medicine. The International Common Disease Alliance’s PRS Task Force will continue to support research enabling the responsible and equitable use of PRSs for the betterment of human health. We look forward to working with cognate groups worldwide to ensure that medical insights from the human genome, exemplified by PRSs, are effective, transparent and available to all.

References

Torkamani, A., Wineinger, N. E. & Topol, E. J. The personal and clinical utility of polygenic risk scores. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 581–590 (2018).

Ganna, A. et al. Multilocus genetic risk scores for coronary heart disease prediction. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33, 2267–2272 (2013).

Abraham, G. et al. Genomic prediction of coronary heart disease. Eur. Heart J. 37, 3267–3278 (2016).

Tada, H. et al. Risk prediction by genetic risk scores for coronary heart disease is independent of self-reported family history. Eur. Heart J. 37, 561–567 (2016).

Inouye, M. et al. Genomic risk prediction of coronary artery disease in 480,000 adults: implications for primary prevention. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 72, 1883–1893 (2018).

Khera, A. V. et al. Genome-wide polygenic scores for common diseases identify individuals with risk equivalent to monogenic mutations. Nat. Genet. 50, 1219–1224 (2018).

Fahed, A. C. et al. Polygenic background modifies penetrance of monogenic variants for tier 1 genomic conditions. Nat. Commun. 11, 3635 (2020).

Mars, N. et al. The role of polygenic risk and susceptibility genes in breast cancer over the course of life. Nat. Commun. 11, 6383 (2020).

Mega, J. L. et al. Genetic risk, coronary heart disease events, and the clinical benefit of statin therapy: an analysis of primary and secondary prevention trials. Lancet 385, 2264–2271 (2015).

Natarajan, P. et al. Polygenic risk score identifies subgroup with higher burden of atherosclerosis and greater relative benefit from statin therapy in the primary prevention setting. Circulation 135, 2091–2101 (2017).

Khera, A. V. et al. Genetic risk, adherence to a healthy lifestyle, and coronary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 2349–2358 (2016).

Thomas, N. J. et al. Frequency and phenotype of type 1 diabetes in the first six decades of life: a cross-sectional, genetically stratified survival analysis from UK Biobank. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 6, 122–129 (2018).

Thomas, N. J. et al. Type 1 diabetes defined by severe insulin deficiency occurs after 30 years of age and is commonly treated as type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 62, 1167–1172 (2019).

Oram, R. A. et al. A Type 1 diabetes genetic risk score can aid discrimination between type 1 and type 2 diabetes in young adults. Diabetes Care 39, 337–344 (2016).

Sharp, S. A. et al. Development and standardization of an improved type 1 diabetes genetic risk score for use in newborn screening and incident diagnosis. Diabetes Care 42, 200–207 (2019).

Ferrat, L. A. et al. A combined risk score enhances prediction of type 1 diabetes among susceptible children. Nat. Med. 26, 1247–1255 (2020).

Abraham, G., Rohmer, A., Tye-Din, J. A. & Inouye, M. Genomic prediction of celiac disease targeting HLA-positive individuals. Genome Med. 7, 72 (2015).

Abraham, G. et al. Accurate and robust genomic prediction of celiac disease using statistical learning. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004137 (2014).

Romanos, J. et al. Improving coeliac disease risk prediction by testing non-HLA variants additional to HLA variants. Gut 63, 415–422 (2014).

Sharp, S. A. et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism genetic risk score to aid diagnosis of coeliac disease: a pilot study in clinical care. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 52, 1165–1173 (2020).

Cánovas, R. et al. Genomic risk scores for juvenile idiopathic arthritis and its subtypes. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 79, 1572–1579 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. Polygenic risk scores have high diagnostic capacity in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219446 (2021).

Damask, A. et al. Patients with high genome-wide polygenic risk scores for coronary artery disease may receive greater clinical benefit from alirocumab treatment in the ODYSSEY OUTCOMES trial. Circulation 141, 624–636 (2020).

Marston, N. A. et al. Predicting benefit from evolocumab therapy in patients with atherosclerotic disease using a genetic risk score: results from the FOURIER trial. Circulation 141, 616–662 (2020).

Jiang, G. et al. Obesity, clinical, and genetic predictors for glycemic progression in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes: a cohort study using the Hong Kong Diabetes Register and Hong Kong Diabetes Biobank. PLoS Med. 17, e1003209 (2020).

Udler, M. S., McCarthy, M. I., Florez, J. C. & Mahajan, A. Genetic risk scores for diabetes diagnosis and precision medicine. Endocr. Rev. 40, 1500–1520 (2019).

McBride, C. M., Koehly, L. M., Sanderson, S. C. & Kaphingst, K. A. The behavioral response to personalized genetic information: will genetic risk profiles motivate individuals and families to choose more healthful behaviors? Annu. Rev. Public Health 31, 89–103 (2010).

Saya, S. et al. A genomic test for colorectal cancer risk: is this acceptable and feasible in primary care? Public Health Genomics 23, 110–121 (2020).

Turnwald, B. P. et al. Learning one’s genetic risk changes physiology independent of actual genetic risk. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3, 48–56 (2019).

Brown, S. N., Jouni, H., Marroush, T. S. & Kullo, I. J. Effect of disclosing genetic risk for coronary heart disease on information seeking and sharing: The MI-GENES Study (Myocardial Infarction Genes). Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. https://doi.org/10.1161/circgenetics.116.001613 (2017)

Widén, E. et al. Communicating polygenic and non-genetic risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease — an observational follow-up study. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.18.20197137 (2020).

Kullo, I. J. et al. Incorporating a genetic risk score into coronary heart disease risk estimates: effect on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels (the MI-GENES Clinical Trial). Circulation 133, 1181–1188 (2016).

Forgetta, V. et al. Development of a polygenic risk score to improve screening for fracture risk: A genetic risk prediction study. PLoS Med. 17, e1003152 (2020).

Lee, A. et al. BOADICEA: a comprehensive breast cancer risk prediction model incorporating genetic and nongenetic risk factors. Genet. Med. 21, 1708–1718 (2019).

Carver, T. et al. CanRisk Tool-A web interface for the prediction of breast and ovarian cancer risk and the likelihood of carrying genetic pathogenic variants. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 30, 469–473 (2021).

Esserman, L. J. The WISDOM Study: breaking the deadlock in the breast cancer screening debate. NPJ Breast Cancer 3, 34 (2017).

Knoppers, B. M., Bernier, A., Granados Moreno, P. & Pashayan, N. Of screening, stratification, and scores. J. Pers. Med. 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11080736 (2021)

Elliott, J. et al. Predictive accuracy of a polygenic risk score-enhanced prediction model vs a clinical risk score for coronary artery disease. JAMA 323, 636–645 (2020).

Sun, L. et al. Polygenic risk scores in cardiovascular risk prediction: A cohort study and modelling analyses. PLoS Med. 18, e1003498 (2021).

Tikkanen, E., Havulinna, A. S., Palotie, A., Salomaa, V. & Ripatti, S. Genetic risk prediction and a 2-stage risk screening strategy for coronary heart disease. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33, 2261–2266 (2013).

Surakka, I. et al. Sex-specific survival bias and interaction modeling in coronary artery disease risk prediction. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.23.21259247 (2021).

Lewis, A. C. F. & Green, R. C. Polygenic risk scores in the clinic: new perspectives needed on familiar ethical issues. Genome Med. 13, 14 (2021).

Lambert, S. A., Abraham, G. & Inouye, M. Towards clinical utility of polygenic risk scores. Hum. Mol. Genet. 28, R133–R142 (2019).

Lewis, C. M. & Vassos, E. Polygenic risk scores: from research tools to clinical instruments. Genome Med. 12, 44 (2020).

Brockman, D. G. et al. Design and user experience testing of a polygenic score report: a qualitative study of prospective users. BMC Med. Genomics 14, 238 (2021).

Ding, Y. et al. Large uncertainty in individual PRS estimation impacts PRS-based risk stratification. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.30.403188 (2021).

Mills, M. C. & Rahal, C. The GWAS Diversity Monitor tracks diversity by disease in real time. Nat. Genet. 52, 242–243 (2020).

Morales, J. et al. A standardized framework for representation of ancestry data in genomics studies, with application to the NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog. Genome Biol. 19, 21 (2018).

Bitarello, B. D. & Mathieson, I. Polygenic scores for height in admixed populations. G3 10, 4027–4036 (2020).

Dikilitas, O. et al. Predictive utility of polygenic risk scores for coronary heart disease in three major racial and ethnic groups. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 106, 707–716 (2020).

Ekoru, K. et al. Genetic risk scores for cardiometabolic traits in sub-Saharan African populations. Int. J. Epidemiol. 50, 1283–1296 (2021).

Mostafavi, H. et al. Variable prediction accuracy of polygenic scores within an ancestry group. eLife 9, e48376 (2020).

Smith, C. E. et al. Using genetic technologies to reduce, rather than widen, health disparities. Health Aff. 35, 1367–1373 (2016).

Borrell, L. N. et al. Race and genetic ancestry in medicine — a time for reckoning with racism. New Engl. J. Med. 384, 474–480 (2021).

Cerdeña, J. P., Plaisime, M. V. & Tsai, J. From race-based to race-conscious medicine: how anti-racist uprisings call us to act. Lancet 396, 1125–1128 (2020).

Meisel, S. F. et al. Explaining, not just predicting, drives interest in personal genomics. Genome Med. 7, 74 (2015).

Abacan, M. et al. The global state of the genetic counseling profession. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 27, 183–197 (2019).

Aizawa, Y., Watanabe, A. & Kato, K. Institutional and social issues surrounding genetic counselors in Japan: current challenges and implications for the global community. Front. Genet. 12, 646177 (2021).

Schwartz, M. L. B. et al. A model for genome-first care: returning secondary genomic findings to participants and their healthcare providers in a large research cohort. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 103, 328–337 (2018).

Heck, P. R. & Meyer, M. N. Population whole exome screening: primary care provider attitudes about preparedness, information avoidance, and nudging. Med. Clin. North Am. 103, 1077–1092 (2019).

Parens, E. & Appelbaum, P. S. On what we have learned and still need to learn about the psychosocial impacts of genetic testing. Hastings Cent. Rep. 49, S2–S9 (2019).

Lineweaver, T. T., Bondi, M. W., Galasko, D. & Salmon, D. P. Effect of knowledge of APOE genotype on subjective and objective memory performance in healthy older adults. Am. J. Psych. 171, 201–208 (2014).

Holtzman, N. A. & Rothstein, M. A. Eugenics and genetic discrimination. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 50, 457–459 (1992).

Naik, R. P. & Haywood, C. Jr. Sickle cell trait diagnosis: clinical and social implications. Hematology Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2015, 160–167 (2015).

Peters, N., Rose, A. & Armstrong, K. The association between race and attitudes about predictive genetic testing. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 13, 361–365 (2004).

Martin, A. R. et al. Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities. Nat. Genet. 51, 584–591 (2019).

Washington, H. A. Medical Apartheid: the Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. 1st edn (Doubleday, 2006).

Matthew, D. B. Two threats to precision medicine equity. Ethn. Dis. 29, 629–640 (2019).

Birney, E., Inouye, M., Raff, J., Rutherford, A. & Scally, A. The language of race, ethnicity, and ancestry in human genetic research. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2106.10041 (2021).

Martin, A. R. et al. Human demographic history impacts genetic risk prediction across diverse populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 100, 635–649 (2017).

Turley, P. et al. Problems with using polygenic scores to select embryos. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 78–86 (2021).

Munday, S. & Savulescu, J. Three models for the regulation of polygenic scores in reproduction. J. Med. Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2020-106588 (2021).

Multhaup, M. L. et al. The Science Behind 23andMe’s Type 2 Diabetes Report Estimating the Likelihood of Developing Type 2 Diabetes with Polygenic Models White Paper 23-19 (2019).

Wand, H. et al. Improving reporting standards for polygenic scores in risk prediction studies. Nature 591, 211–219 (2021).

Buniello, A. et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D1005–D1012 (2019).

Thelwall, M. et al. Is useful research data usually shared? An investigation of genome-wide association study summary statistics. PLoS ONE 15, e0229578 (2020).

Akiyama, M. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 112 new loci for body mass index in the Japanese population. Nat. Genet. 49, 1458–1467 (2017).

Cragun, D. et al. Racial disparities in BRCA testing and cancer risk management across a population-based sample of young breast cancer survivors. Cancer 123, 2497–2505 (2017).

Kerminen, S. et al. Geographic variation and bias in the polygenic scores of complex diseases and traits in Finland. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 104, 1169–1181 (2019).

Sakaue, S. et al. Dimensionality reduction reveals fine-scale structure in the Japanese population with consequences for polygenic risk prediction. Nat. Commun. 11, 1569 (2020).

Marnetto, D. et al. Ancestry deconvolution and partial polygenic score can improve susceptibility predictions in recently admixed individuals. Nat. Commun. 11, 1628 (2020).

Barnes, D. R. et al. Polygenic risk scores and breast and epithelial ovarian cancer risks for carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants. Genet. Med. 22, 1653–1666 (2020).

Ruan, Y. et al. Improving polygenic prediction in ancestrally diverse populations. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.27.20248738 (2021).

Weissbrod, O. et al. Leveraging fine-mapping and non-European training data to improve cross-population polygenic risk scores. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.19.21249483 (2021)

Lambert, S. A. et al. The Polygenic Score Catalog as an open database for reproducibility and systematic evaluation. Nat. Genet. 53, 420–425 (2021).

eMERGE Genomics Risk Assessment and Management Network. https://www.genome.gov/Funded-Programs-Projects/eMERGE-Genomics-Risk-Assessment-and-Management-Network (2021).

Our Future Health. https://ourfuturehealth.org.uk/ (2021).

Lewis, A. C. F. & Green, R. C. Polygenic risk scores in the clinic: Translating risk into action. Hum. Genet. Genom. Adv. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xhgg.2021.100047 (2021).

Kullo, I. J. et al. Incorporating a genetic risk score into coronary heart disease risk estimates. Circulation 133, 1181–1188 (2016).

Cardiovascular Disease: Risk Assessment and Reduction, Including Lipid Modification (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2016).

Mittman, I., Crombleholme, W. R., Green, J. R. & Golbus, M. S. Reproductive genetic counseling to Asian-Pacific and Latin American immigrants. J. Genet. Couns. 7, 49–70 (1998).

Food & Drug Administration. Classify your medical device. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/overview-device-regulation/classify-your-medical-device (2021).

Thorogood, A., Touré, S. B., Ordish, J., Hall, A. & Knoppers, B. Genetic database software as medical devices. Hum. Mutat. 39, 1702–1712 (2018).

Food & Drug Administration. Software as a medical device (SaMD). https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health-center-excellence/software-medical-device-samd (2021).

REGULATION (EU) 2017/745 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCILof 5 April 2017on medical devices, amending Directive 2001/83/EC, Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 and repealing Council Directives 90/385/EEC and 93/42/EEC. (2017).

IMDRF Software as a Medical Device Working Group. ‘Software as a Medical Device’: Possible Framework for Risk Categorization and Corresponding Considerations. http://www.imdrf.org/docs/imdrf/final/technical/imdrf-tech-140918-samd-framework-risk-categorization-141013.pdf (2014)

About IMDRF. http://www.imdrf.org/about/about.asp (2021).

IMDRF Good Regulatory Review Practices Group. Essential Principles of Safety and Performance of Medical Devices and IVD Medical Devices. http://www.imdrf.org/docs/imdrf/final/technical/imdrf-tech-181031-grrp-essential-principles-n47.pdf (2018).

IMDRF SaMD Working Group. Software as a Medical Device (SaMD): Key Definitions. http://www.imdrf.org/docs/imdrf/final/technical/imdrf-tech-131209-samd-key-definitions-140901.pdf (2013)

IMDRF SaMD Working Group. Software as a Medical Device (SaMD): Application of Quality Management System. http://www.imdrf.org/docs/imdrf/final/technical/imdrf-tech-151002-samd-qms.pdf (2015).

IMDRF SaMD Working Group. Software as a Medical Device (SaMD). http://www.imdrf.org/workitems/wi-samd.asp (2021).

Canada, H. Guidance Document: Software as a Medical Device (SaMD). https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/medical-devices/application-information/guidance-documents/software-medical-device-guidance-document.html (2020).

CanRisk Tool. https://canrisk.org/about/ (2020).

Mavaddat, N. et al. Polygenic risk scores for prediction of breast cancer and breast cancer subtypes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 104, 21–34 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the International Common Disease Alliance (ICDA). In particular, we acknowledge the leadership of E. Lander, C. Lindgren, M. Daly, and R. Liao, the ICDA Ethics & Policy Working Group and its co-chairs C. Hutter and M. Zawati, and the administrative support of A. Trankiem. We are also grateful to T. Gjorgjieva for research assistance. Funding: C.J.W. is supported by NIH grants HL135824, HL109946, and HL127564. A.R.M. is supported by NIH grant R00 MH117229. Y.O. is supported by JSPS KAKENHI (19H01021 and 20K21834) and AMED (JP21km0405211, JP21ek0109413, JP21gm4010006, JP21km0405217, JP21ek0410075), JST Moonshot R&D (JPMJMS2021). S.R. is supported by the Academy of Finland Center of Excellence in Complex Disease Genetics (grant numbers 312062 and 336820) and Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (grant number 101016775 ‘INTERVENE’). B.M.K. and P.G.M. are supported by the PERSPECTIVE I&I project, which is funded by the Government of Canada through Genome Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Ministère de l’Économie et de l’Innovation du Québec through Genome Québec, the Quebec Breast Cancer Foundation, the CHU de Quebec Foundation and the Ontario Research Fund. B.M.K. is supported by the Canada Research Chair in Law and Medicine. M.N.M. is supported by Open Philanthropy (010623-00001), the Russell Sage Foundation and the JPB Foundation (1903-13498), and National Institute on Aging (R01AG042568-04 and R24AG065184). The Richards research group is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR: 365825; 409511, 100558, 169303), the McGill Interdisciplinary Initiative in Infection and Immunity (MI4), the Lady Davis Institute of the Jewish General Hospital, the Jewish General Hospital Foundation, the Canadian Foundation for Innovation, the NIH Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Genome Québec, the Public Health Agency of Canada, McGill University, Cancer Research UK (grant number C18281/A29019), and the Fonds de Recherche Québec Santé (FRQS). J.B.R. is supported by a FRQS Mérite Clinical Research Scholarship. Support from Calcul Québec and Compute Canada is acknowledged. TwinsUK is funded by the Welcome Trust, Medical Research Council, European Union, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded BioResource, Clinical Research Facility and Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King’s College London. These funding agencies had no role in the design, implementation, or interpretation of this study. M.I. is supported by the Munz Chair of Cardiovascular Prediction and Prevention. This study was supported by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support (OIS) program and by core funding from: the UK Medical Research Council (MR/L003120/1), the British Heart Foundation (RG/13/13/30194; RG/18/13/33946) and the National Institute for Health Research (Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre at the Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust). This work was supported by Health Data Research UK, which is funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, Department of Health and Social Care (England), Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates, Health and Social Care Research and Development Division (Welsh Government), Public Health Agency (Northern Ireland), British Heart Foundation, and Wellcome. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care. The support of the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) is gratefully acknowledged (ES/T013192/1). S.F. is funded by the Wellcome International Intermediate fellowship (220740/Z/20/Z) at the MRC/UVRI and LSHTM. S.F. is funded by the Wellcome International Intermediate fellowship (220740/Z/20/Z) at the MRC/UVRI and LSHTM. R.A.V. is supported by ANID Chile (FONDEF D10E1007, FONDECYT 1191948, COVID0961). R.A.V. is supported by ANID Chile (FONDEF D10E1007, FONDECYT 1191948, COVID0961).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Introduction: A.C F.L. Benefits: J.B.R., A.C.S., E.W., A.Z. Risks: A.A., D.D., K.K., M.N.M., L.R., G.L.W. Gaps: S.F., P.G.M., C.J.H., B.M.K., M.K., A.R.M., Y.O., S.C.S., R.A.V. Conclusions: M.I.M., S.R., C.N.R. Scientific administration: M.K.B. Co-Chairs: M.I., C.J.W.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The spouse of C.J.W. works at Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. J.B.R. has served as an advisor to GlaxoSmithKline and Deerfield Capital. His institution has received investigator-initiated grant funding from Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, and Biogen for projects unrelated to this research. He is the founder of 5 Prime Sciences. M.M. is an employee of Genentech and a holder of Roche stock.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Medicine thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Karen O’Leary was the primary editor on this article and managed its editorial process and peer review in collaboration with the rest of the editorial team.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Polygenic Risk Score Task Force of the International Common Disease Alliance. Responsible use of polygenic risk scores in the clinic: potential benefits, risks and gaps. Nat Med 27, 1876–1884 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01549-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01549-6

This article is cited by

-

Recent advances in polygenic scores: translation, equitability, methods and FAIR tools

Genome Medicine (2024)

-

Associations of combined polygenic risk score and glycemic status with atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease and ischemic stroke

Cardiovascular Diabetology (2024)

-

Establishment and analysis of a novel diagnostic model for systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis based on machine learning

Pediatric Rheumatology (2024)

-

“For and against” factors influencing participation in personalized breast cancer screening programs: a qualitative systematic review until March 2022

Archives of Public Health (2024)

-

Integration of polygenic and gut metagenomic risk prediction for common diseases

Nature Aging (2024)