Abstract

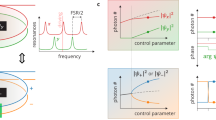

Any system of coupled oscillators may be characterized by its spectrum of resonance frequencies (or eigenfrequencies), which can be tuned by varying the system’s parameters. The relationship between control parameters and the eigenfrequency spectrum is central to a range of applications1,2,3. However, fundamental aspects of this relationship remain poorly understood. For example, if the controls are varied along a path that returns to its starting point (that is, around a ‘loop’), the system’s spectrum must return to itself. In systems that are Hermitian (that is, lossless and reciprocal), this process is trivial and each resonance frequency returns to its original value. However, in non-Hermitian systems, where the eigenfrequencies are complex, the spectrum may return to itself in a topologically non-trivial manner, a phenomenon known as spectral flow. The spectral flow is determined by how the control loop encircles degeneracies, and this relationship is well understood for \(N=2\) (where \(N\) is the number of oscillators in the system)4,5. Here we extend this description to arbitrary \(N\). We show that control loops generically produce braids of eigenfrequencies, and for \(N > 2\) these braids form a non-Abelian group that reflects the non-trivial geometry of the space of degeneracies. We demonstrate these features experimentally for \(N=3\) using a cavity optomechanical system.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The experimental data and numerical calculations are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used for data analysis is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

El-Ganainy, R. et al. Non-Hermitian physics and PT symmetry. Nat. Physics 14, 11–19 (2018).

Miri, M.-A. & Alù, A. Exceptional points in optics and photonics. Science 363, eaar7709 (2019).

Wiersig, J. Review of exceptional point-based sensors. Photon. Res. 8, 1457–1467 (2020).

Kato, T. Perturbation Theory for Linear Operators (Springer-Verlag, 1995).

Dembowski, C. et al. Experimental observation of the topological structure of exceptional points. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 787–790 (2001).

Arnold, V. I. On matrices depending on parameters. Russ. Math. Surv. 26, 29–43 (1971).

Gilmore, R. Catastrophe Theory for Scientists and Engineers 345–366 (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1981).

Ota, Y. et al. Active topological photonics. Nanophotonics 9, 547–567 (2020).

Bahari, B. et al. Nonreciprocal lasing in topological cavities of arbitrary geometries. Science 358, 636–640 (2017).

Naghiloo, M., Abbasi, M., Joglekar, Y. N. & Murch, K. M. Quantum state tomography across the exceptional point in a single dissipative qubit. Nat. Physics 15, 1232–1236 (2019).

Zhong, Q., Özdemir, S. K., Eisfeld, A., Metelmann, A. & El-Ganainy, R. Exceptional-point-based optical amplifiers. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 014070 (2020).

Assawaworrarit, S., Yu, X. & Fan, S. Robust wireless power transfer using a nonlinear parity–time-symmetric circuit. Nature 546, 387–390 (2017).

Xu, H., Mason, D., Jiang, L. & Harris, J. G. E. Topological energy transfer in an optomechanical system with an exceptional point. Nature 537, 80–83 (2016).

Doppler, J. et al. Dynamically encircling an exceptional point for asymmetric mode switching. Nature 537, 76–79 (2016).

Gao, T. et al. Observation of non-Hermitian degeneracies in a chaotic exciton-polariton billiard. Nature 526, 554–558 (2015).

Graefe, E.-M., Günther, U., Korsch, H. J. & Niederle, A. E. A non-Hermitian PT-symmetric Bose–Hubbard model: eigenvalue rings from unfolding higher-order exceptional points. J. Phys. A: Math. Theoret. 41, 255206 (2008).

Heiss, W. D. Chirality of wavefunctions for three coalescing levels. J.Phys. A: Math. Theoret. 41, 244010 (2008).

Cartarius, H., Main, J. & Wunner, G. Exceptional points in the spectra of atoms in external fields. Phys. Rev. A 79, 053408 (2009).

Demange, G. & Graefe, E.-M. Signatures of three coalescing eigenfunctions. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor 45, 025303 (2011).

Lee, S.-Y., Ryu, J.-W., Kim, S. W. & Chung, Y. Geometric phase around multiple exceptional points. Phys. Rev. A 85, 064103 (2012).

Ryu, J.-W., Lee, S.-Y. & Kim, S. W. Analysis of multiple exceptional points related to three interacting eigenmodes in a non-Hermitian Hamiltonian. Phys. Rev. A 85, 042101 (2012).

Zhen, B. et al. Spawning rings of exceptional points out of Dirac cones. Nature 525, 354 (2015).

Ding, K., Zhang, Z. Q. & Chan, C. T. Coalescence of exceptional points and phase diagrams for one-dimensional PT-symmetric photonic crystals. Phys. Rev. B 92, 235310 (2015).

Ding, K., Ma, G., Xiao, M., Zhang, Z. Q. & Chan, C. T. Emergence, coalescence, and topological properties of multiple exceptional points and their experimental realization. Phys. Rev. X 6, 021007 (2016).

Wu, Y.-S. General theory for quantum statistics in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 52, 2103–2106 (1984).

Artin, E. Theory of braids. Ann. Math. 48, 101–126 (1947).

Hatcher, A. Algebraic Topology (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2002).

Hurwitz, A. Ueber Riemann'sche Flächen mit gegebenen Verzweigungspunkten. Math. Ann. 39, 1–60 (1891).

Fox, R. & Neuwirth, L. The braid groups. Math. Scand. 10, 119–126 (1962).

Arnold, V. I. in Vladimir I. Arnold, Collected Works Vol. II (eds Givental, A. B. et al.) 199–220 (Springer-Verlag, 2014).

Aspelmeyer, M., Kippenberg, T. J. & Marquardt, F. Cavity optomechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 1391–1452 (2014).

Nenciu, G. & Rasche, G. On the adiabatic theorem for nonself-adjoint Hamiltonians. J. Phys. A 25, 5741 (1992).

Uzdin, R., Mailybaev, A. & Moiseyev, N. On the observability and asymmetry of adiabatic state flips generated by exceptional points. J. Phys. A 44, 435302 (2011).

Berry, M. V. & Uzdin, R. Slow non-Hermitian cycling: exact solutions and the Stokes phenomenon. J. Phys. A 44, 435303 (2011).

Emmanouilidou, A., Zhao, X. G., Ao, P. & Niu, Q. Steering an Eigenstate to a destination. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 1626 (2000).

Berry, M. V. Transitionless quantum driving. J. Phys. A 42, 365303 (2009).

Ibáñez, S., Martínez-Garaot, S., Chen, X., Torrontegui, E. & Muga, J. G. Shortcuts to adiabaticity for non-Hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. A 84, 023415 (2011).

Wu, B., Liu, J. & Niu, Q. Geometric phase for adiabatic evolutions of general quantum states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 140402 (2005).

Graefe, E.-M. & Korsch, H. J. Crossing scenario for a nonlinear non-Hermitian two-level system. Czech. J. Phys. 56, 1007–1020 (2006).

Wang, H., Assawaworrarit, S. & Fan, S. Dynamics for encircling an exceptional point in a nonlinear non-Hermitian system. Optic. Lett. 44, 638–641 (2019).

Garling, D. J. H. Galois Theory and its Algebraic Background 2nd edn 123, 124 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Milnor, J. Singular Points of Complex Hypersurfaces (Princeton Univ. Press, 1968).

Henry, P. A. Measuring the Knot of Non-Hermitian Degeneracies and Non-Abelian Braids. Thesis, Yale University, New Haven, CT (2022).

Buchmann, L. F. & Stamper-Kurn, D. M. Nondegenerate multimode optomechanics. Phys. Rev. A 92, 013851 (2015).

Shkarin, A. B. et al. Optically mediated hybridization between two mechanical modes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 013602 (2014).

Zhong, Q., Khajavikhan, M., Christodoulides, D. N. & El-Ganainy, R. Winding around non-Hermitian singularities. Nat. Commun. 9, 4808 (2018).

Wang, S. et al. Arbitrary order exceptional point induced by photonic spin–orbit interaction in coupled resonators. Nat. Commun. 10, 832 (2019).

Xiao, Z., Li, H., Kottos, T. & Alù, A. Enhanced sensing and nondegraded thermal noise performance based on PT-symmetric electronic circuits with a sixth-order exceptional point. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 213901 (2019).

Makris, K. G., El-Ganainy, R., Christodoulides, D. N. & Musslimani, Z. H. Beam dynamics in PT symmetric optical lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 103904 (2008).

Szameit, A., Rechtsman, M. C., Bahat-Treidel, O. & Segev, M. PT-symmetry in honeycomb photonic lattices. Phys. Rev. A 84, 021806(R) (2011).

Leykam, D., Bliokh, K. Y., Huang, C., Chong, Y. D. & Nori, F. Edge modes, degeneracies, and topological numbers in non-Hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 040401 (2017).

Chen, W., Lu, H.-Z. & Hou, J. M. Topological semimetals with a double-helix link. Phys. Rev. B 96, 041102(R) (2017).

Bi, R., Yan, Z., Lu, L. & Wang, Z. Nodal-knot semimetals. Phys. Rev. B. 96, 201305(R) (2017).

Carlström, J. & Bergholtz, E. J. Exceptional links and twisted Fermi ribbons in non-Hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. A. 98, 042114 (2018).

Shen, H., Zhen, B. & Fu, L. Topological band theory for non-Hermitian Hamiltonians. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 146402 (2018).

Wojcik, C. C., Sun, X.-Q., Bzdušek, T. & Fan, S. Homotopy characterization of non-Hermitian Hamiltonians. Phys. Rev. B. 101, 205417 (2020).

Hu, H. & Zhao, E. Knots and Non-Hermitian Bloch bands. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 010401 (2021).

Wang, K., Dutt, A., Wojcik, C. C. & Fan, S. Topological complex-energy braiding of non-Hermitian bands. Nature 598, 59–64 (2021).

Zhang, X., Li, G., Liu, Y., Tai, T., Thomale, R. & Lee, C. H. Tidal surface states as fingerprints of non-Hermitian nodal knot metals. Commun. Phys. 4, 47 (2021).

Nash, L. M. et al. Topological mechanics of gyroscopic metamaterials. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 14495–14500 (2015).

Mitchell, N. P., Turner, A. M. & Irvine, W. T. M. Real-space origin of topological band gaps, localization, and reentrant phase transitions in gyroscopic metamaterials. Phys. Rev. E. 104, 025007 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Air Force Office of Scientific Research award no. FA9550-15-1-0270, Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship no. N00014-20-1-2628 and National Science Federation grant no. DMR-1724923. We thank Y. Wang for helpful discussions, and the Yale Center for Research Computing for guidance and use of the research computing infrastructure, specifically M. Guy. J.G.E.H. thanks H. Vanderbilt. J.H. is now supported by Howard Hughes Medical Institute Janelia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.R. and J.G.E.H. conceived the project. Y.S.S.P., J.H., P.A.H., C.G., L.J. and N.K. designed the experiment. Y.S.S.P., P.A.H. and C.G. took the data. Y.S.S.P., J.H., P.A.H., C.G. and Y.Z. analysed and modelled the data. J.G.E.H. supervised the project. All authors contributed to the writing of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 The trefoil knot of degeneracies and the eigenvalue braids for a three-mode system.

a, At a fixed distance from the three-fold degeneracy, the control space for the spectrum is \({{\mathscr{S}}}^{3}\) (shown here in stereographic projection). The degeneracies in this space are all two-fold and form a trefoil knot (orange). Three control loops (green, red, blue), each parameterized by \(0\le s\le 1\) share a common basepoint (black cross).b–d, Evolution of the eigenvalues as \(s\) is varied around each loop in a. The black crosses show \({\boldsymbol{\lambda }}\) at the basepoint. The dashed lines are guides to the eye. This figure is calculated from the characteristic polynomial of a three-mode system (see the Supplementary Information).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Locating EP3.

The quantity \(d\left({\boldsymbol{\Psi }}\right)\) (which ideally vanishes at \({{\boldsymbol{\Psi }}}_{{\rm{EP}}3}\)), measured on six 2D sheets passing through \({{\boldsymbol{\Psi }}}_{{\rm{EP}}3}^{\left({\rm{est}}\right)},\) the location of the \({{\rm{EP}}}_{3}\) that is estimated from scanning individual components of \({\boldsymbol{\Psi }}\) (Methods). Top row: raw data. Middle row: data after outlier rejection and smoothing described in the Supplementary Information. The black circles show the minima that are located using the algorithm described in the Supplementary Information. Bottom row: the values of \(d\) calculated from the optomechanical model.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Locating EP3 (perspective view).

The data of Extended Data Fig. 2 arranged in 3D to illustrate the minimum of \(d\left({\boldsymbol{\Psi }}\right)\) in the neighbourhood of the experimentally estimated location of the \({{\rm{EP}}}_{3}\).

Extended Data Fig. 4 The locations of the sixty-one 2D sheets within \(\boldsymbol{\mathscr{S}}\).

The sheets are colour-coded by the 3D face in which they lie. a, The sheets are shown within each of the eight 3D faces of \({\mathscr{S}}\). b, The same sheets as in a, shown using the ‘rectilinear stereographic’ projection of Fig. 3b. Note that in this projection, all of the sheets are contained within the plot’s bounding box. c, The same sheets, shown using the stereographic projection of Fig. 3a. The thin black lines show the boundary of each sheet. Thin grey lines show where a sheet exits the plot’s bounding box. The projections are described in Methods. The data from these sheets are shown in Video 5 of the Supplementary Information.

Extended Data Fig. 5 The knot of EP2 via four different signatures.

The same data as in Fig. 3a, b, but in separate plots for the EP2 locations determined by each of the four different signatures. a, Zeroes of the discriminant \(D\). b, Phase vortices of the discriminant \(D\). c, Zeroes of the eigenvector indicator \(E\). d, Phase vortices of the eigenvector indicator \(E\). The quantities \(D\) and \(E\) are defined in the main text, and additional discussion of \(E\) is in the Supplementary Information. The projections used here are the same as in Fig. 3a, b. The solid curve is the same in all eight panels, and is the best-fit knot shown in Fig. 3a, b.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Comparison of measured and calculated braids.

a–f, The same panels as in Fig. 3c–h. They show the control loops (green, red, and blue in a–c) in relation to the measured knot (yellow circles) and the best-fit knot (orange curve). d–f, The resulting eigenvalue braids. g–i, The eigenvalue spectrum as calculated using the optomechanical parameters determined from fitting the knot of EP2. The dashed lines are guides to the eye.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Additional braids of eigenvalues.

a–c, Three loops (green, red, blue), each from a different homotopy class. They share a common basepoint (black sphere) and are non-self-intersecting. The measured knot \({\mathscr{K}}\) (yellow circles) and the best-fit knot (orange curve) are shown for reference. The projection used here is the same as in Fig. 3a. d–f, The eigenvalue spectrum \({\boldsymbol{\lambda }}({\boldsymbol{\Psi }})\) as \({\boldsymbol{\Psi }}\) is varied around a loop. The variable \(\xi \) indexes the values of \({\boldsymbol{\Psi }}\) (along each loop) at which \({\boldsymbol{\lambda }}\) is measured. The black crosses show \({\boldsymbol{\lambda }}\) at the start and stop of the loop. The dashed lines are guides to the eye. The 1\(\sigma \) confidence intervals for \({\boldsymbol{\lambda }}\) are comparable to the size of the plotted points. The braids realized are: \({\sigma }_{1}^{2}\) (d), \({\sigma }_{1}^{3}\) (e), and \({\sigma }_{2}{\sigma }_{1}^{2}\) (f).

Extended Data Fig. 8 Details of the experimental setup.

a, The optical and electronic layout. Red arrows: beam path from the ‘probe’ laser. Blue arrows: beam path from the ‘control’ laser. Purple arrows: overlapped beam path of the two lasers. Black arrows: electronic lines. Grey region: cryostat containing the optical cavity and membrane. The various components are described in the Supplementary Information. b, The optical spectrum. Red lines: tones produced from the probe laser. Blue lines: tones produced from the control laser. The tones and their generation are described in Methods and the Supplementary Information. Grey curves: the two cavity modes used in this work.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Characterizing the optomechanical coupling.

Here the cavity is driven with a single control tone, whose detuning (from the cavity resonance) is \(\Delta \). Each panel shows the measured deviation of the (real or imaginary part of the) mechanical mode’s eigenvalue from its bare value (that is, from the relevant component of \({\widetilde{{\boldsymbol{\lambda }}}}^{\left(0\right)}\), whose numerical value is written in the panel). The error bars show the 1\(\sigma \) confidence interval for each data point. A global fit to standard optomechanical theory gives the bare resonance frequencies \({\widetilde{{\boldsymbol{\lambda }}}}^{\left(0\right)}\) and the optomechanical couplings \({\boldsymbol{g}}\). A detailed description of this procedure is in the Supplementary Information.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Control loops from Fig. 3c–e.

The three control loops in Fig. 3c–e were assembled from data taken in the two 2D sheets shown here. The two sheets’ common border is shown as the dashed grey line. Each small grey disc represents a value of \({\boldsymbol{\Psi }}\) at which \({\boldsymbol{\lambda }}\) was measured (that is, a ‘pixel’ in the 2D sheet). The black crosses show the location of the EP2 in these sheets as determined by the minima-finding algorithm described in the Supplementary Information.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This Supplementary Information file describes various technical aspects of the experimental apparatus, the data acquisition, analysis and fitting.

Supplementary Video 1

Laying out the hypersurface 𝓢 in terms of the experimental parameters. See Supplementary Information PDF for the full video caption.

Supplementary Video 2

Visualizing the EP2 knot in the rectilinear stereographic projection. See Supplementary Information PDF for the full video caption.

Supplementary Video 3

This video is simply a rotating version of Fig. 3a,b from the main text.

Supplementary Video 4

This video is simply a rotating version of Fig. 3c–h from the main text.

Supplementary Video 5

The 61 2D data sheets used to locate the ψEP2 in the hypersurface 𝓢. See Supplementary Information PDF for full video caption.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Patil, Y.S.S., Höller, J., Henry, P.A. et al. Measuring the knot of non-Hermitian degeneracies and non-commuting braids. Nature 607, 271–275 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04796-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04796-w

This article is cited by

-

Exceptional classifications of non-Hermitian systems

Communications Physics (2024)

-

Optomechanical realization of the bosonic Kitaev chain

Nature (2024)

-

Third-order exceptional line in a nitrogen-vacancy spin system

Nature Nanotechnology (2024)

-

Resolving the topology of encircling multiple exceptional points

Nature Communications (2024)

-

A second wave of topological phenomena in photonics and acoustics

Nature (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.