Abstract

For many years, bleeding has been perceived as an unavoidable consequence of strategies aimed at reducing thrombotic complications in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). However, the paradigm has now shifted towards bleeding being recognized as a prognostically unfavourable event to the same extent as having a new or recurrent ischaemic or thrombotic complication. As such, in parallel with progress in device and drug development for PCI, there is clinical interest in developing strategies that maximize not only the efficacy but also the safety (for example, by minimizing bleeding) of any antithrombotic treatment or procedural aspect before, during or after PCI. In this Review, we discuss contemporary data and aspects of bleeding avoidance strategies in PCI, including risk stratification, timing of revascularization, pretreatment with antiplatelet agents, selection of vascular access, choice of coronary stents and antithrombotic treatment regimens.

Key points

-

For years, concerns about thrombosis and recurrent ischaemia in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) have prevailed, prompting the use of potent antithrombotic strategies and long durations of dual antiplatelet therapy.

-

Remarkable improvements in the way in which PCI is performed have led to a new interest in investigating strategies that target bleeding, especially in patients at higher risk of bleeding.

-

Patients at high risk of bleeding should be promptly identified to define appropriate bleeding prevention strategies.

-

Bleeding avoidance strategies include actions targeted at minimizing the risk of bleeding before, during and after PCI.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Capodanno, D., Alfonso, F., Levine, G. N., Valgimigli, M. & Angiolillo, D. J. ACC/AHA versus ESC Guidelines on dual antiplatelet therapy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 72, 2915–2931 (2018).

Capodanno, D. et al. Dual-pathway inhibition for secondary and tertiary antithrombotic prevention in cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 17, 242–257 (2020).

Knuuti, J. et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 41, 407–477 (2020).

Costa, F. et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy duration based on ischemic and bleeding risks after coronary stenting. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 73, 741–754 (2019).

Valgimigli, M. et al. Trade-off of myocardial infarction vs. bleeding types on mortality after acute coronary syndrome: lessons from the Thrombin Receptor Antagonist for Clinical Event Reduction in Acute Coronary Syndrome (TRACER) randomized trial. Eur. Heart J. 38, 804–810 (2017).

Buccheri, S., Capodanno, D., James, S. & Angiolillo, D. J. Bleeding after antiplatelet therapy for the treatment of acute coronary syndromes: a review of the evidence and evolving paradigms. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 18, 1171–1189 (2019).

Giustino, G. et al. Characterization of the average daily ischemic and bleeding risk after primary PCI for STEMI. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 70, 1846–1857 (2017).

Palmerini, T. et al. Stent thrombosis with drug-eluting stents. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 62, 1915–1921 (2013).

Stone, G. W. et al. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 226–235 (2011).

Patel, M. R. et al. ACC/AATS/AHA/ASE/ASNC/SCAI/SCCT/STS 2017 appropriate use criteria for coronary revascularization in patients with stable ischemic heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 69, 2212–2241 (2017).

Subherwal, S. et al. Baseline risk of major bleeding in non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: the CRUSADE (Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress ADverse outcomes with Early implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines) bleeding score. Circulation 119, 1873–1882 (2009).

Mehran, R. et al. A risk score to predict bleeding in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55, 2556–2566 (2010).

Costa, F. et al. Derivation and validation of the predicting bleeding complications in patients undergoing stent implantation and subsequent dual antiplatelet therapy (PRECISE-DAPT) score: a pooled analysis of individual-patient datasets from clinical trials. Lancet 389, 1025–1034 (2017).

Urban, P. et al. Defining high bleeding risk in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation 140, 240–261 (2019).

Urban, P. et al. Assessing the risks of bleeding vs thrombotic events in patients at high bleeding risk after coronary stent implantation: the ARC-high bleeding risk trade-off model. JAMA Cardiol. 6, 410–419 (2021).

Raposeiras-Roubín, S. et al. Development and external validation of a post-discharge bleeding risk score in patients with acute coronary syndrome: the BleeMACS score. Int. J. Cardiol. 254, 10–15 (2018).

Yeh, R. W. et al. Development and validation of a prediction rule for benefit and harm of dual antiplatelet therapy beyond 1 year after percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA 315, 1735–1749 (2016).

Baber, U. et al. Coronary thrombosis and major bleeding after PCI with drug-eluting stents risk scores from paris. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67, 2224–2234 (2016).

Ducrocq, G. et al. Risk score to predict serious bleeding in stable outpatients with or at risk of atherothrombosis. Eur. Heart J. 31, 1257–1265 (2010).

Natsuaki, M. et al. Prediction of thrombotic and bleeding events after percutaneous coronary intervention: CREDO-Kyoto thrombotic and bleeding risk scores. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7, e008708 (2018).

Subherwal, S. et al. Temporal trends in and factors associated with bleeding complications among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 59, 1861–1869 (2012).

Das, D., Savu, A., Bainey, K. R., Welsh, R. C. & Kaul, P. Temporal trends in in-hospital bleeding and transfusion in a contemporary Canadian ST-elevation myocardial infarction patient population. CJC Open 3, 479–487 (2021).

Capodanno, D. & Angiolillo, D. J. Tailoring duration of DAPT with risk scores. Lancet 389, 987–989 (2017).

Ueki, Y. et al. Validation of bleeding risk criteria (ARC-HBR) in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention and comparison with contemporary bleeding risk scores. EuroIntervention 16, 371–379 (2020).

Cao, D. et al. Validation of the Academic Research Consortium high bleeding risk definition in contemporary PCI patients. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 75, 2711–2722 (2020).

Natsuaki, M. et al. Application of the Academic Research Consortium high bleeding risk criteria in an all-comers registry of percutaneous coronary intervention. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 12, e008307 (2019).

Corpataux, N. et al. Validation of high bleeding risk criteria and definition as proposed by the Academic Research Consortium for high bleeding risk. Eur. Heart J. 41, 3743–3749 (2020).

Collet, J.-P. et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur. Heart J. 42, 1289–1367 (2021).

Capodanno, D. & Angiolillo, D. J. Pretreatment with antiplatelet drugs in invasively managed patients with coronary artery disease in the contemporary era: review of the evidence and practice guidelines. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 8, e002301 (2015).

Parodi, G. et al. Comparison of prasugrel and ticagrelor loading doses in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 61, 1601–1606 (2013).

Capodanno, D. & Angiolillo, D. J. Reviewing the controversy surrounding pre-treatment with P2Y12 inhibitors in acute coronary syndrome patients. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 14, 811–820 (2016).

Montalescot, G. et al. Pretreatment with prasugrel in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 999–1010 (2013).

Montalescot, G. et al. Prehospital ticagrelor in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 1016–1027 (2014).

Tarantini, G. et al. Timing of oral P2Y12 inhibitor administration in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 76, 2450–2459 (2020).

Lemesle, G. et al. Optimal timing of intervention in NSTE-ACS without pre-treatment. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 13, 907–917 (2020).

Valgimigli, M. Pretreatment with P2Y 12 inhibitors in non-ST-segment-elevation acute coronary syndrome is clinically justified. Circulation 130, 1891–1903 (2014).

Valgimigli, M. et al. Radial versus femoral access and bivalirudin versus unfractionated heparin in invasively managed patients with acute coronary syndrome (MATRIX): final 1-year results of a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 392, 835–848 (2018).

Andò, G. & Capodanno, D. Radial access reduces mortality in patients with acute coronary syndromes results from an updated trial sequential analysis of randomized trials. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 9, 660–670 (2016).

Andò, G. & Capodanno, D. Radial versus femoral access in invasively managed patients with acute coronary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 163, 932–940 (2015).

Ferrante, G. et al. Radial versus femoral access for coronary interventions across the entire spectrum of patients with coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JACC. Cardiovasc. Interv. 9, 1419–1434 (2016).

Chiarito, M. et al. Radial versus femoral access for coronary interventions: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 97, 1387–1396 (2021).

Jhand, A. et al. Meta-analysis of transradial vs transfemoral access for percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 141, 23–30 (2021).

Neumann, F.-J. et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. EuroIntervention 14, 1435–1534 (2019).

Mignatti, A., Friedmann, P. & Slovut, D. P. Targeting the safe zone: a quality improvement project to reduce vascular access complications. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 91, 27–32 (2018).

Rao, S. V. & Stone, G. W. Arterial access and arteriotomy site closure devices. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 13, 641–650 (2016).

Montalescot, G. et al. Enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin in elective percutaneous coronary intervention. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 1006–1017 (2006).

Montalescot, G. et al. Intravenous enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin in primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the international randomised open-label ATOLL trial. Lancet 378, 693–703 (2011).

Silvain, J. et al. Efficacy and safety of enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin during percutaneous coronary intervention: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 344, e553 (2012).

Capodanno, D. & De Caterina, R. Bivalirudin for acute coronary syndromes: premises, promises and doubts. Thromb. Haemost. 113, 698–707 (2015).

Erlinge, D. et al. Bivalirudin versus heparin monotherapy in myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 1132–1142 (2017).

Briguori, C. et al. Novel approaches for preventing or limiting events (Naples) III trial: randomized comparison of bivalirudin versus unfractionated heparin in patients at increased risk of bleeding undergoing transfemoral elective coronary stenting. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 8, 414–423 (2015).

Shahzad, A. et al. Unfractionated heparin versus bivalirudin in primary percutaneous coronary intervention (HEAT-PPCI): an open-label, single centre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 384, 1849–1858 (2014).

Valgimigli, M. et al. Bivalirudin or unfractionated heparin in acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 997–1009 (2015).

Bikdeli, B. et al. Individual patient data pooled analysis of randomized trials of bivalirudin versus heparin in acute myocardial infarction: rationale and methodology. Thromb. Haemost. 120, 348–362 (2020).

Wiviott, S. D. et al. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 2001–2015 (2007).

Wallentin, L. et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 1045–1057 (2009).

Schüpke, S. et al. Ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 1524–1534 (2019).

Menichelli, M. et al. Age- and weight-adapted dose of prasugrel versus standard dose of ticagrelor in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Ann. Intern. Med. 173, 436–444 (2020).

Capodanno, D. et al. Management of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation patients undergoing PCI. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 74, 83–99 (2019).

Angiolillo, D. J. et al. Antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with oral anticoagulation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation 143, 583–596 (2021).

Sarafoff, N. et al. Triple therapy with aspirin, prasugrel, and vitamin K antagonists in patients with drug-eluting stent implantation and an indication for oral anticoagulation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 61, 2060–2066 (2013).

Gimbel, M. et al. Clopidogrel versus ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients aged 70 years or older with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (POPular AGE): the randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 395, 1374–1381 (2020).

Capranzano, P. & Angiolillo, D. J. Evidence and recommendations for uninterrupted versus interrupted oral anticoagulation in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 14, 764–767 (2021).

Bhatt, D. L. et al. Antibody-based ticagrelor reversal agent in healthy volunteers. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 1825–1833 (2019).

Capodanno, D., Milluzzo, R. P. & Angiolillo, D. J. Intravenous antiplatelet therapies (glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors and cangrelor) in percutaneous coronary intervention: from pharmacology to indications for clinical use. Ther. Adv. Cardiovasc. Dis. 13, 1753944719893274 (2019).

Groves, E. M. et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of acquired thrombocytopenia after percutaneous coronary intervention: a pooled, patient-level analysis of the CHAMPION trials (cangrelor versus standard therapy to achieve optimal management of platelet inhibition). Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 11, e005635 (2018).

Vaduganathan, M. et al. Cangrelor with and without glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 69, 176–185 (2017).

Vaduganathan, M. et al. Evaluation of ischemic and bleeding risks associated with 2 parenteral antiplatelet strategies comparing cangrelor with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors: an exploratory analysis from the CHAMPION trials. JAMA Cardiol. 2, 127–135 (2017).

Angiolillo, D. J. et al. Impact of cangrelor overdosing on bleeding complications in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the CHAMPION trials. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 40, 317–322 (2015).

Steg, P. G. et al. Effect of cangrelor on periprocedural outcomes in percutaneous coronary interventions: a pooled analysis of patient-level data. Lancet 382, 1981–1992 (2013).

Franchi, F. et al. Platelet inhibition with cangrelor and crushed ticagrelor in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the CANTIC study. Circulation 139, 1661–1670 (2019).

Urban, P. et al. Polymer-free drug-coated coronary stents in patients at high bleeding risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 2038–2047 (2015).

Varenne, O. et al. Drug-eluting stents in elderly patients with coronary artery disease (SENIOR): a randomised single-blind trial. Lancet 391, 41–50 (2018).

Ariotti, S. et al. Is bare-metal stent implantation still justifiable in high bleeding risk patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention? JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 9, 426–436 (2016).

Windecker, S. et al. Polymer-based or polymer-free stents in patients at high bleeding risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1208–1218 (2020).

Morice, M.-C., Urban, P., Greene, S., Schuler, G. & Chevalier, B. Why are we still using coronary bare-metal stents? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 61, 1122–1123 (2013).

Krucoff, M. W. et al. Global approach to high bleeding risk patients with polymer-free drug-coated coronary stents. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 13, e008603 (2020).

Kozuma, K. et al. 1-Year safety of 3-month dual antiplatelet therapy followed by aspirin or P2Y12 receptor inhibitor monotherapy using a bioabsorbable polymer sirolimus-eluting stent. Circ. J. 85, 19–26 (2020).

Kandzari, D. E. et al. One-month dual antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention with zotarolimus-eluting stents in high-bleeding-risk patients. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 13, e009565 (2020).

Mehran, R. & Valgimigli, M. The XIENCE short DAPT program: XIENCE 90/28 evaluating the safety of 3- and 1-month DAPT in HBR patients (TCT Connect, 2020).

Kirtane, A. J. et al. Primary results of the EVOLVE short DAPT study: evaluation of 3-month dual antiplatelet therapy in high bleeding risk patients treated with a bioabsorbable polymer-coated everolimus-eluting stent. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 14, e010144 (2021).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04137510 (2021).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04500912 (2021).

Capodanno, D. et al. Trial design principles for patients at high bleeding risk undergoing PCI. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 76, 1468–1483 (2020).

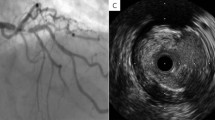

Buccheri, S. et al. Clinical outcomes following intravascular imaging-guided versus coronary angiography-guided percutaneous coronary intervention with stent implantation: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis of 31 studies and 17,882 patients. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 10, 2488–2498 (2017).

Mauri, L. et al. Twelve or 30 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stents. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 2155–2166 (2014).

Fiedler, K. A. et al. Duration of triple therapy in patients requiring oral anticoagulation after drug-eluting stent implantation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 65, 1619–1629 (2015).

Hoshi, T. et al. Short-duration triple antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation patients who require coronary stenting: results of the SAFE-A study. EuroIntervention 16, e164–e172 (2020).

Byrne, R. A. COBRA-REDUCE: randomized trial of COBRA PzF stenting to reduce duration of triple therapy (TCT Connect, 2020).

Frigoli, E. et al. Design and rationale of the management of high bleeding risk patients post bioresorbable polymer coated stent implantation with an abbreviated versus standard DAPT regimen (MASTER DAPT) study. Am. Heart J. 209, 97–105 (2019).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03287167 (2020).

Gwon, H.-C. et al. Six-month versus 12-month dual antiplatelet therapy after implantation of drug-eluting stents. Circulation 125, 505–513 (2012).

Kim, B.-K. et al. A new strategy for discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 60, 1340–1348 (2012).

Kedhi, E. et al. Six months versus 12 months dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stent implantation in ST-elevation myocardial infarction (DAPT-STEMI): randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. BMJ 363, k3793 (2018).

Hahn, J.-Y. et al. 6-month versus 12-month or longer dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome (SMART-DATE): a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 391, 1274–1284 (2018).

De Luca, G. et al. Final results of the randomised evaluation of short-term dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with acute coronary syndrome treated with a new generation stent (REDUCE) trial. EuroIntervention 15, e990–e998 (2019).

Lemmert, M. E. et al. Reduced duration of dual antiplatelet therapy using an improved drug-eluting stent for percutaneous coronary intervention of the left main artery in a real-world, all-comer population: rationale and study design of the prospective randomized multicenter I. Am. Heart J. 187, 104–111 (2017).

Feres, F. et al. Three vs twelve months of dual antiplatelet therapy after zotarolimus-eluting stents. JAMA 310, 2510–2522 (2013).

Colombo, A. et al. Second-generation drug-eluting stent implantation followed by 6- versus 12-month dual antiplatelet therapy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 64, 2086–2097 (2014).

Schulz-Schüpke, S. et al. ISAR-SAFE: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 6 vs. 12 months of clopidogrel therapy after drug-eluting stenting. Eur. Heart J. 36, 1252–1263 (2015).

Han, Y. et al. Six versus 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after implantation of biodegradable polymer sirolimus-eluting stent: randomized substudy of the I-LOVE-IT 2 trial. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 9, e003145 (2016).

Hong, S.-J. et al. 6-month versus 12-month dual-antiplatelet therapy following long everolimus-eluting stent implantation. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 9, 1438–1446 (2016).

Nakamura, M. et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy for 6 versus 18 months after biodegradable polymer drug-eluting stent implantation. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 10, 1189–1198 (2017).

Didier, R. et al. 6- versus 24-month dual antiplatelet therapy after implantation of drug-eluting stents in patients nonresistant to aspirin. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 10, 1202–1210 (2017).

Lee, B.-K. et al. Safety of six-month dual antiplatelet therapy after second-generation drug-eluting stent implantation: OPTIMA-C randomised clinical trial and OCT substudy. EuroIntervention 13, 1923–1930 (2018).

Hong, M. One-month dual antiplatelet therapy followed by aspirin monotherapy after drug-eluting stent implantation: randomized one-month DAPT trial (American Heart Association, 2020).

Capodanno, D. & Angiolillo, D. J. Dual antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation and PCI. Lancet 394, 1300–1302 (2019).

Dewilde, W. J. et al. Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 381, 1107–1115 (2013).

Capodanno, D. et al. Aspirin-free strategies in cardiovascular disease and cardioembolic stroke prevention. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 15, 480–496 (2018).

Hindricks, G. et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J. 42, 373–498 (2021).

Gibson, C. M. et al. Prevention of bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 2423–2434 (2016).

Cannon, C. P. et al. Dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran after PCI in atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 1513–1524 (2017).

Lopes, R. D. et al. Antithrombotic therapy after acute coronary syndrome or PCI in atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 1509–1524 (2019).

Vranckx, P. et al. Edoxaban-based versus vitamin K antagonist-based antithrombotic regimen after successful coronary stenting in patients with atrial fibrillation (ENTRUST-AF PCI): a randomised, open-label, phase 3b trial. Lancet 394, 1335–1343 (2019).

Alexander, J. H. et al. Risk/benefit tradeoff of antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation early and late after an acute coronary syndrome or percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation 141, 1618–1627 (2020).

Peterson, B. E. et al. Evaluation of dual versus triple therapy by landmark analysis in the RE-DUAL PCI Trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 14, 768–780 (2021).

Gargiulo, G. et al. Safety and efficacy outcomes of double vs. triple antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation following percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant-based randomized clinical trials. Eur. Heart J. 40, 3757–3767 (2019).

Capodanno, D. et al. Safety and efficacy of double antithrombotic therapy with non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 9, e017212 (2020).

Watanabe, H. et al. Effect of 1-month dual antiplatelet therapy followed by clopidogrel vs 12-month dual antiplatelet therapy on cardiovascular and bleeding events in patients receiving PCI: the STOPDAPT-2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 321, 2414–2427 (2019).

Hahn, J.-Y. et al. Effect of P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy vs dual antiplatelet therapy on cardiovascular events in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the SMART-CHOICE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 321, 2428–2437 (2019).

Vranckx, P. et al. Ticagrelor plus aspirin for 1 month, followed by ticagrelor monotherapy for 23 months vs aspirin plus clopidogrel or ticagrelor for 12 months, followed by aspirin monotherapy for 12 months after implantation of a drug-eluting stent: a multicentre, open-la. Lancet 392, 940–949 (2018).

Franzone, A. et al. Ticagrelor alone or conventional dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with stable or acute coronary syndromes. EuroIntervention 16, 627–633 (2020).

Mehran, R. et al. Ticagrelor with or without aspirin in high-risk patients after PCI. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 2032–2042 (2019).

Kim, B.-K. et al. Effect of ticagrelor monotherapy vs ticagrelor with aspirin on major bleeding and cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome. JAMA 323, 2407–2416 (2020).

Valgimigli, M. et al. Ticagrelor monotherapy versus dual-antiplatelet therapy after PCI. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 14, 444–456 (2021).

O’Donoghue, M. L., Murphy, S. A. & Sabatine, M. S. The safety and efficacy of aspirin discontinuation on a background of a P2Y12 inhibitor in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation 142, 538–545 (2020).

Khan, S. U. et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention and drug-eluting stents. Circulation 142, 1425–1436 (2020).

Cuisset, T. et al. Benefit of switching dual antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome: the TOPIC (timing of platelet inhibition after acute coronary syndrome) randomized study. Eur. Heart J. 38, 3070–3078 (2017).

Sibbing, D. et al. Guided de-escalation of antiplatelet treatment in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (TROPICAL-ACS): a randomised, open-label, multicentre trial. Lancet 390, 1747–1757 (2017).

Claassens, D. M. F. et al. A genotype-guided strategy for oral P2Y12 inhibitors in primary PCI. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 1621–1631 (2019).

Kim, H.-S. et al. Prasugrel-based de-escalation of dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome (HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS): an open-label, multicentre, non-inferiority randomised trial. Lancet 396, 1079–1089 (2020).

Pereira, N. L. et al. Effect of genotype-guided oral P2Y12 inhibitor selection vs conventional clopidogrel therapy on ischemic outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: the TAILOR-PCI randomized clinical trial. JAMA 324, 761–771 (2020).

Sibbing, D. et al. Updated expert consensus statement on platelet function and genetic testing for guiding P2Y12 receptor inhibitor treatment in percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 12, 1521–1537 (2019).

Angiolillo, D. J. et al. International expert consensus on switching platelet P2Y12 receptor-inhibiting therapies. Circulation 136, 1955–1975 (2017).

Galli, M. et al. Guided versus standard antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 397, 1470–1483 (2021).

Pannach, S. et al. Management and outcome of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients taking oral anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs. J. Gastroenterol. 52, 1211–1220 (2017).

Wärme, J. et al. Helicobacter pylori screening in clinical routine during hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction. Am. Heart J. 231, 105–109 (2021).

Grosser, T. et al. Drug resistance and pseudoresistance: an unintended consequence of enteric coating aspirin. Circulation 127, 377–385 (2013).

Angiolillo, D. J. et al. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic assessment of a novel, pharmaceutical lipid-aspirin complex: results of a randomized, crossover, bioequivalence study. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 48, 554–562 (2019).

Bhatt, D. L. et al. Enteric coating and aspirin nonresponsiveness in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 69, 603–612 (2017).

Cryer, B. et al. Low-dose aspirin-induced ulceration is attenuated by aspirin-phosphatidylcholine: a randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 106, 272–277 (2011).

Sinnaeve, P. et al. Subcutaneous selatogrel inhibits platelet aggregation in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 75, 2588–2597 (2020).

Milluzzo, R. P., Franchina, G. A., Capodanno, D. & Angiolillo, D. J. Selatogrel, a novel P2Y12 inhibitor: a review of the pharmacology and clinical development. Expert Opin Investig. Drugs 29, 537–546 (2020).

Roux, S. & Bhatt, D. L. Self-treatment for acute coronary syndrome: why not? Eur. Heart J. 41, 2144–2145 (2020).

Mayer, K. et al. Efficacy and safety of revacept, a novel lesion-directed competitive antagonist to platelet glycoprotein VI, in patients undergoing elective percutaneous coronary Intervention for stable ischemic heart disease: the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled ISAR-PLASTER phase 2 trial. JAMA Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2021.0475 (2021).

Ray, W. A. et al. Association of proton pump inhibitors with reduced risk of warfarin-related serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology 151, 1105–1112.e10 (2016).

Olsen, A.-M. S. et al. Risk of gastrointestinal bleeding associated with oral anticoagulation and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with atrial fibrillation: a nationwide study. Eur. Hear. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 6, 292–300 (2020).

Bhatt, D. L. et al. Clopidogrel with or without omeprazole in coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 1909–1917 (2010).

Moayyedi, P. et al. Pantoprazole to prevent gastroduodenal events in patients receiving rivaroxaban and/or aspirin in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 157, 403–412.e5 (2019).

Glikson, M. et al. EHRA/EAPCI expert consensus statement on catheter-based left atrial appendage occlusion – an update. EuroIntervention 15, 1133–1180 (2020).

Franzone, A. et al. Ticagrelor alone versus dual antiplatelet therapy from 1 month after drug-eluting coronary stenting. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 74, 2223–2234 (2019).

Zwart, B., Parker, W. A. E. & Storey, R. F. New antithrombotic drugs in acute coronary syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 9, 2059 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.C. and D.J.A. researched data for the article and wrote the manuscript. All the authors contributed substantially to discussions of content and reviewed and/or edited the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

D.C. reports advisory board or speaker’s honoraria from Amgen, Biotronik, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Menarini and Sanofi. D.L.B. discloses the following relationships: advisory board of Cardax, CellProthera, Cereno Scientific, Elsevier Practice Update Cardiology, Level Ex, Medscape Cardiology, MyoKardia, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma and Regado Biosciences; board of directors of Boston VA Research Institute, Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care and TobeSoft; chair of AHA Quality Oversight Committee; membership of data monitoring committees for the Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute, for the PORTICO trial, funded by St. Jude Medical, now Abbott), the Cleveland Clinic (including for the ExCEED trial, funded by Edwards), Contego Medical (chair, PERFORMANCE 2), Duke Clinical Research Institute, Mayo Clinic, Mount Sinai School of Medicine (for the ENVISAGE trial, funded by Daiichi Sankyo) and Population Health Research Institute; honoraria from ACC (Senior Associate Editor, Clinical Trials and News, ACC.org; Vice-Chair, ACC Accreditation Committee), the Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute; RE-DUAL PCI clinical trial steering committee funded by Boehringer Ingelheim; AEGIS-II executive committee funded by CSL Behring), Belvoir Publications (Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter), Canadian Medical and Surgical Knowledge Translation Research Group (clinical trial steering committees), Duke Clinical Research Institute (clinical trial steering committees, including for the PRONOUNCE trial, funded by Ferring Pharmaceuticals), HMP Global (Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Invasive Cardiology), Journal of the American College of Cardiology (Guest Editor, Associate Editor), K2P (Co-Chair, interdisciplinary curriculum), Level Ex, Medtelligence/ReachMD (CME steering committees), MJH Life Sciences, Population Health Research Institute (for the COMPASS operations committee, publications committee, steering committee, and USA national co-leader, funded by Bayer), Slack Publications (Chief Medical Editor, Cardiology Today’s Intervention), Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care (Secretary/Treasurer) and WebMD (CME steering committees); others including Clinical Cardiology (Deputy Editor), NCDR-ACTION Registry Steering Committee (Chair), VA CART Research and Publications Committee (Chair); research funding from Abbott, Afimmune, Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cardax, Chiesi, CSL Behring, Eisai, Ethicon, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Forest Laboratories, Fractyl, HLS Therapeutics, Idorsia, Ironwood, Ischemix, Lexicon, Lilly, Medtronic, MyoKardia, Owkin, Pfizer, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, Synaptic and The Medicines Company; royalties from Elsevier (editor, Cardiovascular Intervention: A Companion to Braunwald’s Heart Disease); site co-investigator for Biotronik, Boston Scientific, CSI, St. Jude Medical (now Abbott) and Svelte; trustee for ACC; and unfunded research for FlowCo, Merck, Novo Nordisk and Takeda. C.M.G. reports research support from Johnson & Johnson and consulting support from AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, Janssen and Bayer. T.K. reports research grant from Abbott Vascular and Boston Scientific. R.M. reports institutional research grants from Abbott Laboratories, Abiomed, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Beth Israel Deaconess, Bristol Myers Squibb, CERC, Chiesi, Concept Medical, CSL Behring, DSI, Medtronic, Novartis Pharmaceuticals and OrbusNeich, Zoll; consultant fees from Boston Scientific, Cine-Med Research, Janssen Scientific Affairs, Medscape/WebMD; consultant fees paid to the institution from Abbott Laboratories, Abiomed (spouse), Bayer (spouse), Beth Israel Deaconess, Bristol Myers Squibb, CardiaWave, Chiesi, Concept Medical, DSI, Duke University, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Novartis and Spectranetics/Philips/Volcano Corp; equity of <1% from Applied Therapeutics, Elixir Medical, STEL and CONTROLRAD (spouse); consulting (no fee) for Regeneron Pharmaceuticals; and Associate Editor for ACC and AMA. P.G.S. discloses the following relationships: research grant from Amarin, Bayer, Sanofi and Servier; speaking or consulting fees from Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer/Janssen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Idorsia, Myokardia, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, PhaseBio, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi and Servier. P.U. reports consulting honoraria from Biosensors and MedAlliance, and CEC honoraria from Edwards Lifesciences and Cardialysis; honoraria as medical co-director at CERC; and is a shareholder of MedAlliance. S.W. reports research and educational grants to the institution from Abbott, Amgen, Bayer, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cardinal Health, Cardiovalve, CSL Behring, Daiichi Sankyo, Edwards Lifesciences, Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, Querbet, Polares, Sanofi, Terumo and Sinomed, and unpaid advisory board membership and/or unpaid membership of the steering/executive group of trials funded by Abbott, Abiomed, Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cardiovalve, Edwards Lifesciences, MedAlliance, Medtronic, Novartis, Polares, Sinomed, V-Wave and Xeltis, but has not received personal payments from pharmaceutical companies or device manufacturers; he is also member of the steering/executive committee group of several investigator-initiated trials that receive funding from industry without impact on his personal remuneration; he is an unpaid member of the Pfizer Research Award selection committee in Switzerland. D.J.A. has received payment as an individual as a consulting fee or honorarium from Abbott, Amgen, Aralez, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biosensors, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Chiesi, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Haemonetics, Janssen, Merck, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Pfizer, Sanofi and The Medicines Company, and for participation in review activities from CeloNova and St. Jude Medical; has received institutional payments as grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biosensors, CeloNova, CSL Behring, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, Eli-Lilly, Gilead, Idorsia, Janssen, Matsutani Chemical Industry Co., Merck, Novartis, Osprey Medical, Renal Guard Solutions and the Scott R. MacKenzie Foundation. All the other authors report no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Cardiology thanks D. Alexopoulos, J. P. Collet and K. Huber for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Capodanno, D., Bhatt, D.L., Gibson, C.M. et al. Bleeding avoidance strategies in percutaneous coronary intervention. Nat Rev Cardiol 19, 117–132 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-021-00598-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-021-00598-1

This article is cited by

-

Optimizing antithrombotic therapy in patients with coexisting cardiovascular and gastrointestinal disease

Nature Reviews Cardiology (2024)

-

Clinical and Pre-Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Bentracimab

Clinical Pharmacokinetics (2023)

-

P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention

Nature Reviews Cardiology (2022)

-

Abbreviating DAPT reduces the risk of bleeding

Nature Reviews Cardiology (2021)