Abstract

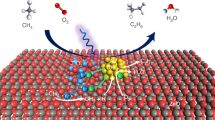

Nonoxidative coupling of methane (NOCM) is a highly important process to simultaneously produce multicarbons and hydrogen. Although oxide-based photocatalysis opens opportunities for NOCM at mild condition, it suffers from unsatisfying selectivity and durability, due to overoxidation of CH4 with lattice oxygen. Here, we propose a heteroatom engineering strategy for highly active, selective and durable photocatalytic NOCM. Demonstrated by commonly used TiO2 photocatalyst, construction of Pd–O4 in surface reduces contribution of O sites to valence band, overcoming the limitations. In contrast to state of the art, 94.3% selectivity is achieved for C2H6 production at 0.91 mmol g–1 h–1 along with stoichiometric H2 production, approaching the level of thermocatalysis at relatively mild condition. As a benchmark, apparent quantum efficiency reaches 3.05% at 350 nm. Further elemental doping can elevate durability over 24 h by stabilizing lattice oxygen. This work provides new insights for high-performance photocatalytic NOCM by atomic engineering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Methane, the predominant constituent of natural gas, shale gas and combustible ice, has provoked increasing attention as an important feedstock for energy supply and chemical production1,2. Conventionally, direct conversion of CH4 to value-added multicarbon (C2+) compounds is achieved via thermocatalysis through nonoxidative or oxidative routes3,4,5. Nevertheless, undesired side reactions, such as carbon deposition in nonoxidative routes and CH4 overoxidation in oxidative routes, inevitably occur in the thermochemical processes, concomitantly with insufficient selectivity and yield of C2+ compounds. Meanwhile, high temperatures (700−1110 °C) and pressure (>1 MPa) are required for such thermocatalytic approaches, resulting in high energy consumption and capital input6,7. Under such circumstances, future development demands new approaches to direct methane conversion in mild condition.

In this context, photocatalytic nonoxidative coupling of methane (NOCM), which requires only solar energy as energy input and CH4 as a reactant, emerges as an appealing approach for the production of value-added C2+ hydrocarbons and hydrogen8,9. Given strong oxidation capability and lattice oxygen reactivity, metal oxide photocatalysts have been mainly explored for photocatalytic NOCM10,11,12. Despite that, the use of metal oxide unavoidably results in unsatisfying photocatalytic NOCM selectivity and durability. In detail, the valence band of metal oxide is predominantly composed of O 2p states13,14, enabling the photogenerated holes to concentrate on O sites for cleaving C–H bond of CH4. Once C–H bonds are cleaved, overoxidation of CH4 would readily take place at the O sites while consuming lattice oxygen15,16. As an outcome, photocatalytic reactivity decays by losing lattice oxygen while overoxidation products, e.g., CO2 and CO arise17,18, restricting the product selectivity and catalyst durability of the oxide-based photocatalytic NOCM.

To overcome these limitations, the valence band of oxide photocatalysts should be rationally engineered. In the past decade, metallic single atoms (SAs) loaded nanostructures have attracted tremendous interest for photocatalysis19, one of whose advantages is their capability of tailoring photocatalyst electronic structure20. The incorporation of metallic d-orbital structure shows more occupied state in valence band maximum (VBM) and provides additional active sites in photocatalysts21,22. Against this background, we propose that tailoring VBM of oxide photocatalyst with metallic SAs could be a feasible approach to reduce the contribution of O 2p states to valence band near-surface, suppressing the overoxidation of CH4 with lattice oxygen.

Here, taking TiO2, a widely used oxide photocatalyst as a proof-of-concept model, we report that incorporation of Pd SAs in oxide surface lattice can overcome the limitations upon screening a series of metallic SAs toward photocatalytic NOCM. According to the simulation of the material, the Pd–O4 unit demonstrates the largest contribution to VBM of surface TiO2 so as to accumulate photogenerated holes, which in turn dissociate C–H bonds at Pd SAs. Furthermore, the unique feature of Pd in stabilizing ∙CH3 allows it to be the reaction site for coupling of reaction intermediates. As a result, the Pd SAs modified catalyst (Pd1/TiO2) exhibits the highest performance toward C2H6 production, with an apparent quantum efficiency of 3.05% at 350 nm and an extraordinary C2H6 production rate of 0.91 mmol g–1 h–1. More importantly, the occupied state of Pd–O4 in VBM suppresses the overoxidation of CH4 with lattice oxygen, which offers 94.3% selectivity toward C2H6 production and substantially improved stability of oxide photocatalyst. Furthermore, a pertinent element (i.e., Si) is selected to dope the TiO2 lattice for further stabilizing subsurface lattice oxygen to elevate catalyst durability over 24 h.

Results

Material screening and photocatalytic performance

To screen metallic SAs with the largest contribution to VBM, we employ density functional theory (DFT) calculation to examine various SAs modified TiO2 (M1/TiO2) catalysts near the surface. The key to the reconstruction of VBM is the coordination of SAs with lattice oxygen. To this end, we select TiO2 (001) plane as the surface for decorating metallic SAs because it contains relatively loosely packed oxygen atoms as illustrated in Fig. 1a, which allows the formation of the M–O bond between the metallic SAs and lattice oxygen of TiO223. For metallic nanoparticles, such a bond structure can hardly be formed so that they are mainly loaded on the TiO2 surface (Pdn/TiO2). Figure 1b, c shows the simulated density of states (DOS) for various M1/TiO2 catalysts (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for other calculation results). For M1/TiO2 catalysts, the composition of VBM is significantly altered although the decorated metallic SAs induce impurity states in the bandgap of TiO2. Pd–O4 unit exhibits the largest contribution to VBM among all the studied catalysts, implying the potential of accumulating photogenerated holes. Notably, for the Pd nanoparticles, the photogenerated electrons would be concentrated at Pd due to the formation of Schottky junction (Fig. 1c)19,24, while the photogenerated holes are remained in TiO2. Such an assumption is verified by Pd 3d X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Fig. 1d). Specifically, under light irradiation, the binding energy for Pd1/TiO2 is positively shifted for 0.2 eV, indicating the accumulation of photogenerated holes at Pd–O4 unit. In contrast, Pdn/TiO2 displays negatively shifted binding energy in Pd 3d XPS upon light irradiation (Supplementary Fig. 2). The charge accumulation is also proven by infrared spectroscopy with CO probe (Supplementary Fig. 3). Based on the theoretical simulation results, we prepare a series of metal SAs (Pd, Au, Rh, Ir, and Ru) modified TiO2 for photocatalytic NOCM as shown in Fig. 1e. Generally, the TiO2 loaded with Pd SAs, which owns the largest contribution to VBM of TiO2, demonstrates the highest activity and selectivity toward CH4−to−C2H6 conversion. Moreover, computational and experimental results show that TiO2 (001) is the optimal surface for loading Pd SAs as compared with other TiO2 facets (Supplementary Fig. 4).

a Schematic illustration for TiO2 (001)-based models—pristine TiO2 (top), Pd1/TiO2 (middle), and Pdn/TiO2 (bottom). b, c Total density of states (TDOS) of Pd1/TiO2 (b) and Pdn/TiO2 (c). The red line represents the contribution of metals to TDOS, in which Pd–O4 unit show the highest proportion in VBM (highlighted by blue arrow). d Pd 3d XPS spectra of Pd1/TiO2 and Pdn/TiO2 under light irradiation indicating charge accumulation. e The relationship of metal contribution in VBM and photocatalytic NOCM performance for various M1/TiO2 as well as Pdn/TiO2. Reaction condition: 0.1 MPa CH4, 3 h light irradiation. The error bars represent the standard deviation of the experiments.

In this context, we focus on the investigation of the photocatalytic NOCM process on Pd1/TiO2 in reference to pristine TiO2 and Pdn/TiO2 with similar Pd content (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 1). Typically, all the samples are based on TiO2 nanosheets dominated with (001) surface (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). To resolve the structure of Pd SAs, the Pd1/TiO2 catalyst is examined by a series of microscopic and spectroscopic techniques. The high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images of Pd1/TiO2 indicate that the Pd elements are atomically dispersed on the support (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 8), which is also verified by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping (Fig. 2b). To investigate the coordination environment of Pd in Pd1/TiO2 catalyst, the catalyst is further characterized by synchrotron radiation-based X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 9). As revealed by extended X-ray adsorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra in R space for Pd K-edge (Fig. 2c), only a single peak for Pd–O coordination (1.53 Å) can be observed on Pd1/TiO2, confirming the domination of isolated Pd atoms in Pd1/TiO2 catalyst. According to the fitting, the average coordination number is determined to be 4 (Supplementary Table 2)25. The presence of isolated Pd atoms on the TiO2 can be further affirmed via investigating the CO adsorption behavior on the catalysts (Supplementary Fig. 2)26,27. We thus conclude that the Pd atoms in Pd1/TiO2 are isolated from each other and coordinated with four O atoms in TiO2 to form Pd−O4 units.

a–c STEM image (a), elemental mappings (b) and Pd K-edge EXAFS spectra in R space (c) of Pd1/TiO2. The isolated Pd atoms are marked with red circles in (a). d, e The C2H6 production rates (d) and the corresponding selectivity of C2H6, C2H4, and CO2 (e) in 0.1 MPa CH4. f The AQEs for CH4−to−C2H6 conversion with their UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectra as references. The error bars represent the standard deviation of the experiments.

Upon acquiring structural information for the catalyst, the detailed photocatalytic NOCM measurements are performed at room temperature under 600 mW cm–2 xenon arc lamp irradiation. As shown in Fig. 2d, pristine TiO2 nanosheets exhibit a negligible C2H6 production rate. This performance is due to the large contribution of O atoms to VBM, which leads to the direct participation of the lattice oxygen in CH4 conversion. In detail, photogenerated holes in TiO2 are predominantly concentrated at O atoms to cleave C−H bonds of CH4. As the activated methyl species can hardly desorb from O sites, they are vulnerable to overoxidation. As a result, CO2 emerges as the major product with nearly 100% selectivity as shown in Fig. 2e. Since Pd nanoparticles play the role of electron accumulation, Pdn/TiO2 does not suppress overoxidation to CO2 but promotes C2H6 production owing to dehydrogenation and stabilization of ∙CH3 at Pd nanoparticles28,29. As such, Pdn/TiO2 exhibits an initial rate of ~0.18 mmol g–1 h–1 for C2H6 production in the first 1 h, which decreases gradually after 2 h of light irradiation due to lattice oxygen consumption by overoxidation (Fig. 2d). The overoxidation is evidenced by a large amount of produced CO2 with a selectivity of about 32% (Fig. 2e). In stark contrast, Pd1/TiO2 displays a very high C2H6 production rate of ~0.91 mmol g–1 h–1 at the initial 1 h of light irradiation (Fig. 2d). More importantly, catalyst stability has been dramatically improved (Supplementary Fig. 10), yielding C2H6 at 2.6 mmol g–1 with over 93% carbon balance (Supplementary Table 3). The high C2H6 production rate over Pd1/TiO2 can be maintained with a 33-fold scale-up of catalyst usage under appropriate reaction conditions (Supplementary Fig. 11). These results clearly demonstrate that the modification of TiO2 VBM with Pd SAs can allow the CH4 conversion to proceed on the Pd instead of the lattice oxygen of TiO2, substantially suppressing overoxidation of CH4 with lattice oxygen. As a direct outcome, the C2H6 selectivity for Pd1/TiO2 is maintained at ~94.3% (Fig. 2e). Notably, we observe that the measured amount of produced H2 is approximately in theoretically stoichiometric ratio with the production of C2H6 and trace CO2 (Supplementary Fig. 12), further confirming the superiority of Pd SAs in enhancing photocatalytic NOCM performance of TiO2. As a result, turnover number (TON) reaches as high as 186 toward C2H6 evolution over the Pd1/TiO2 catalyst for 3 h light irradiation. In terms of light utilization, the Pd1/TiO2 catalyst achieves an AQE of 3.05% under 350-nm light irradiation (Fig. 2f). Furthermore, the photocatalytic performance is directly proportional to the light intensity, demonstrating that the activation of CH4 is driven by photogenerated holes under mild condition (Supplementary Fig. 13). The outstanding NOCM performance indicates that Pd SAs modification enables an efficient C–C coupling process and suppresses CH4 overoxidation. To trace the origin of carbonaceous products, we further perform a series of control and isotope-labeling experiments (Supplementary Figs. 14–16), showing that the CH4 is indeed the source of the produced C2H6.

Insight into photocatalytic NOCM mechanism

The information gleaned above has recognized the superior performance of CH4 conversion by modifying VBM of TiO2 with Pd SAs. We are now in a position to look into the reaction mechanism over TiO2 with a focus on the role of Pd SAs. Based on photoelectrochemical measurements (Supplementary Fig. 17), it is demonstrated that the presence of Pd can greatly enhance the photogenerated charge carrier separation efficiency of the TiO2, and the Pd1/TiO2 demonstrates the highest efficiency due to the homogeneous dispersion of Pd SAs on the TiO2. To gain insight into the intermediates of photocatalytic NOCM on Pd1/TiO2, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) measurement is performed to investigate possible radicals by using 5,5′-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) as a radical scavenger in a liquid-phase reaction condition30. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 18, both the characteristic signals of ∙CH3 and ∙OH can be detected using Pd1/TiO2. Given that the ∙OH is formed due to the presence of water, this observation indicates that the surface ∙CH3 is the key intermediate for CH4 coupling31,32. In comparison, only ∙OH is detected for pristine TiO2 and Pdn/TiO2, suggesting the high efficiency of CH4 dissociation on Pd1/TiO2.

Furthermore, in situ diffuse reflectance-infrared Fourier-transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) is employed to investigate the intermediates for photocatalytic NOCM. The catalysts are exposed to CH4 under dark condition firstly for adsorption. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 19, apart from the peak at 1302 cm–1 corresponding to C–H deformation vibration of CH4, the peak at 1541 cm–1 can ascribed to the symmetric deformation vibrational mode of CH4 on metal oxide surface17,33. Upon light irradiation, the vibrational modes of CH2/CH3 deformation at 1469 and 1423 cm–1 appear immediately (Fig. 3a), indicating that CH4 is rapidly dissociated over Pd1/TiO2 surface by photogenerated charge carriers8. Furthermore, the peak of C–C stretching (876 cm–1) appears and gradually increase with the prolonged light irradiation, demonstrating C–C coupling on catalyst surface8,34. Meanwhile, the slight growth of C=O (1671 cm–1) and C–O (1042 cm–1) stretching vibrational modes are assigned to the species for CO2 formation, suggesting the sluggish overoxidation of CH4 on Pd1/TiO235,36,37. In contrast, intense C=O and C–O stretching vibration signals can be observed for Pdn/TiO2 (Fig. 3b), while the CH2/CH3 intermediates can hardly be resolved in the DRIFTS spectra for pristine TiO2 (Supplementary Fig. 20). Taken together, photocatalytic NOCM results and in situ DRIFTS characterizations clearly reveal that Pd SAs modification can promote the coupling route and diminish the overoxidation of CH4 under light irradiation. The surface hydrocarbon species are also monitored by in situ near ambient pressure XPS (NAP-XPS) studies. After introducing 45 Pa CH4 into NAP-XPS chamber under the dark, the peak of gas-phase CH4 (287.0 eV) is observed38. Subsequently, the peak of surface ∙CHx species at 285.6 eV appears and is gradually boosted along with light irradiation (Fig. 3c), further corroborating the dissociation of CH4 on catalyst surface39,40. Notably, the fitting curves of the C 1 s spectrum show the absence of C–O formation on the surface (Supplementary Fig. 21). This suggests that no C–O specie is involved in the CH4−to−C2H6 conversion.

To have a full image of the coupling process of NOCM, we perform DFT calculation to examine CH4 dissociation and intermediate coupling over Pd1/TiO2 with the assistance of photogenerated holes. In our calculation, Pd atom is stabilized in the fourfold hollow sites of TiO2 (001) face to form Pd–O4 complex. As demonstrated in our material screening, such a metal−support interaction modulates the VBM of TiO2. We, therefore, calculate the potential energy diagram of CH4 coupling reaction on the Pd1/TiO2 surface (Fig. 4a), based on the atomic configurations in Fig. 4b. When CH4 is adsorbed on Pd atom, the C–H bond is dissociated by the oxidation of photogenerated holes on Pd–O4 unit, releasing H atom and leaving Pd–CH3 (IM2) on the surface. Given the steric effect for adsorption, the activation of the second CH4 requires a substantially higher energy of 1.35 eV (i.e., green line between IM3 and IM4). As a result, the extremely high activation energy of 1.74 eV (167.9 kJ mol–1) from initial state to TS state hinders the NOCM process under dark condition. However, taking the extra potential provided by the photogenerated holes into account (Supplementary Fig. 22), the energy barrier of the step turns into downhill (i.e., red line between IM3 to IM4), followed by the C–C coupling over Pd atom (TS to IM5) and C2H6 desorption. Meanwhile, we also experimentally measure the activation energy of the NOCM process under light irradiation condition. A relatively low value of 9.54 kJ mol–1 is acquired (Supplementary Fig. 23). The dramatic decrease of activation energy under light irradiation suggests that the photogenerated carriers play a crucial role in overcoming the energy barrier of NOCM. Nevertheless, the simulation suggests that the efficiency of C–C coupling should be associated with the probability of the second CH4 reaching the active site, depending on the concentration of gaseous CH4. In our photocatalytic tests, we indeed recognize that the yield of C2H6 decreases when reducing the concentration of filling CH4 (Supplementary Fig. 24).

Performance enhancement with lattice oxygen stabilization

As revealed by the photocatalytic NOCM, the C2H6 is the primary product along with the minor CO2 using Pd1/TiO2. Note that no gaseous oxygen or other oxidizing agent is present in the reactor, implying that the overoxidation of CH4 to CO2 is derived from lattice oxygen of the catalyst15,16,17,18. Such oxidation by lattice oxygen is inevitably accompanied with its consumption that will eventually reduce photocatalytic performance. To this end, we investigate the time-dependent NOCM on Pd1/TiO2 (Supplementary Figs. 25 and 26), showing that the performance of the Pd1/TiO2 decays after 6 h of reaction and can be recovered by heating the catalyst in air. As such, the photocatalytic performance of Pd1/TiO2 is well maintained for eight cyclic tests with each cycle of 3 h followed by a recovering process (Fig. 5a). Furthermore, the characterizations including aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM, CO adsorption DRIFTS and EXAFS for Pd1/TiO2 after the cyclic tests show the chemical state of Pd is well preserved with single dispersion (Supplementary Figs. 27−29). Moreover, the H2–temperature-programmed reduction (H2–TPR) analysis shows that the Pd–O species in Pd1/TiO2 are more stable than Pd oxide, indicating the stability of Pd–O4 units (Supplementary Fig. 30). Apparently, the overoxidation of CH4 to CO2 can be suppressed by Pd1/TiO2 through the contribution of Pd SAs to VBM but still occurs via the consumption of lattice oxygen. On the basis of DFT calculation (Fig. 4b, IM2), we can elucidate the mechanism for the consumption of lattice oxygen on Pd1/TiO2 that one of Pd–O bonds in Pd–O4 unit is fractured to steady the state of [Pd…∙CH3] after CH4 activation on the Pd atom. As such, the exposed O atom from the fractured Pd–O, together with other O atoms uncoordinated with Pd atoms, can be consumed to produce CO2 via overoxidation, resulting in performance decay.

a Production rates and selectivity of C2H6 in the cyclic tests by Pd1/TiO2. Each cycle lasts 3 h, between which the catalyst is treated in air. b In situ EPR signals for Pd1/TiO2 catalyst in 0.1 MPa CH4 under different conditions. The inset is the formation of O vacancy during the reaction. c In situ high-resolution O 1 s XPS spectra for Pd1/TiO2 catalyst with different light illumination time in 45 Pa CH4. d, e The comparison of C2H6 (d) and CO2 (e) production between Pd1/TiO2 and Pd1/ST. f The photocatalytic NOCM by Pd1/ST and Pd1/TiO2 benchmarked against the photocatalytic NOCM and the mild-condition thermocatalytic NOCM in literature. The temperatures in thermocatalysis represent the reaction temperatures applied in those works.

To further prove the mechanism, we employ in situ EPR to examine the structural changes of the catalysts during photocatalytic NOCM. Upon light irradiation, Pd1/TiO2 shows the signal for −O•– radical sites in anatase crystals at g = 1.999, which is derived from the separation of photogenerated charge carriers and can participate in CH4 oxidation (Fig. 5b)41. After turning light off, the signal for the single electron trapped O defects at g = 2.001 can be observed, manifesting the emergence of O vacancies after the photocatalytic process42. A similar observation is also acquired for pristine TiO2 (Supplementary Fig. 31). Furthermore, the appearance of the O vacancy during the reaction can be further attested via the in situ NAP-XPS, corresponding with the results of in situ EPR (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Figs. 32 and 33)23,43. As determined by temperature-programmed oxidation (TPO), 0.7 wt.% of lattice oxygen has been consumed in the photocatalytic process (Supplementary Fig. 34). Moreover, the location of the formed O vacancies is determined by 17O magic angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance (17O MAS NMR) and EPR spectra. It turns out that the consumption of lattice oxygen preferentially takes place at the O atoms near the Ti sites with 2-fold oxide coordination (OTi2) on the catalyst surface (Supplementary Fig. 35).

Given the experimental results indicating the CH4 overoxidation process, we further conduct DFT calculation to simulate the possible steps of CH4–to–CO2 conversion with lattice oxygen consumption. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 36, taking the O site adjacent to Ti atom as an example, the photogenerated holes are required to provide extra potential for CH4 dehydrogenation at the O site; otherwise, the high energy barrier of further steps will inhibit the process thermodynamically. Specifically, the activation of the last hydrogen atom in CH4 requires a high energy of 1.82 eV (i.e., green line between O-IM4 and O-IM5), which is the rate-determining step for overoxidation process under dark condition. However, the energy barrier of this step turns into downhill with the assistance of photogenerated holes (i.e., red line between O-IM4 and O-IM5), and the bonding between the adsorbed CH4 and the second lattice oxygen becomes the rate-determining step with the energy barrier of 1.12 eV (i.e., O-IM3 to O-IM4). This indicates that the stabilization of the lattice oxygen can weaken the bonding between CH4 and O site and suppress the overoxidation of CH4 to CO2 under light irradiation.

The mechanistic study suggests that the stabilization of lattice oxygen should be an efficient method for further suppressing the CH4 overoxidation and enhancing the stability of Pd1/TiO2. To this end, we employ the elemental doping via Si to further stabilize O atoms of TiO2 (Supplementary Fig. 37)44. As shown in Fig. 5d as well as Supplementary Figs. 38 and 39, incorporating Si into Pd1/TiO2 (Pd1/ST) can mitigate CH4 overoxidation to a large extent and maintain photocatalytic activity for up to 24 h. The effect of Si doping on suppressing CH4 overoxidation is further verified by the comparison of CO2 production between Pd1/TiO2 and Pd1/ST (Fig. 5e). Moreover, the computational results demonstrate that the incorporation of Si can further increase the energy barrier of the rate-determining step in the conversion process of CH4 to CO2 as compared with that of Pd1/TiO2, indicating that the presence of Si atoms in TiO2 can suppress the overoxidation of CH4 by stabilizing the lattice oxygen atoms (Supplementary Fig. 40). It is worthwhile to note that the photocatalytic performance of optimized Pd1/TiO2 and Pd1/ST well exceed the existing photocatalysts for NOCM and reach the level of thermocatalysts working between 923 and 1073 K (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Table 4)45,46,47,48,49.

Discussion

To address the limitations in photocatalytic NOCM, we have developed a photocatalyst based on TiO2 by modifying valence band near-surface with Pd–O4 units, which achieves highly efficient light-driven CH4 conversion to C2H6 under mild condition. Benefiting from the contribution of Pd–O4 units to valence band, the single Pd sites display the accumulation of photogenerated holes, which are able to dissociate C–H bond and adsorb ∙CH3 for C2H6 formation. In the meantime, reducing the role of O atoms in valence band substantially suppresses the overoxidation of CH4 with lattice oxygen, dramatically improving catalytic durability. As a result, the catalyst exhibits the ultrahigh C2H6 production rate of 0.91 mmol g–1 h–1 and selectivity of 94.3%, reaching the level of thermocatalytic NOCM at relatively mild condition. Fundamentally, the in situ generation and retention of O vacancies on photocatalysts during photocatalytic NOCM have been experimentally observed and assigned to the consumption of lattice oxygen for CO2 generation, providing key information for further performance enhancement. Interestingly, the overoxidation process can be suppressed by steadying subsurface lattice oxygen with lattice doping, further enhancing catalyst reusability. This work highlights the importance of rational lattice engineering to tuning reaction pathways, and is expected to offer guideline for the design of high-performance catalysts toward NOCM at mild condition.

Methods

Catalysts preparation

TiO2 nanosheets were prepared by a simple hydrothermal method. Typically, 10 mL of tetrabutyl titanate (TBOT) was mixed with 1.6 mL HF with stirring for 30 min. Then the solution was transferred into a 50 mL Teflon-lined autoclave and reaction at 180 °C for 24 h. After that, the resulting white slurry was centrifuged and washed with distilled water several times and dried in a vacuum oven. For the synthesis of Pd1/TiO2 catalyst, 20 mg TiO2 nanosheets were dispersed in 5 mL dilute ammonia solution (pH = 10.5) to form a homogeneous white suspension. Separately, 20 μL Pd(NO3)2 solution (21.1 mM) was attenuated with dilute ammonia solution (pH = 10.5) to 3 mL. Next, the 3 mL mixture was injected into the TiO2 suspension with stirring by using the syringe pump at a rate of 1 mL h–1, followed by vigorous stirring for another 3.5 h. The obtained slurry was then washed with distilled water until the pH turns neutral and dried in the oven at 60 °C. After that, the collected solid was calcined in air at 300 °C in air for 2 h. The Pdn/TiO2 was prepared by reduction of NaBH4. Generally, 60 mg of TiO2 nanosheets were dispersed in 30 mL distilled water, then 60 μL Pd(NO3)2 solution (21.1 mM) was added into the mixture and further react with 5 mg NaBH4. The product was separated by centrifugation, washed with water several times and dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C overnight. The other metal SAs loaded M1/TiO2 catalysts were synthesized with the similar electrostatic adsorption wet impregnation technique by adding different metallic precursor solution with approximate content.

For Si-doping TiO2, 150 μL Tetraethoxysilane, 10 mL TBOT, and 1.2 mL HF were added into anhydrous ethanol (20 mL) with stirring for 30 min. The precursor solution was transferred into 50 mL Teflon-lined autoclave and reaction at 180 °C for 2 h. The Pd1/ST was obtained by a similar procedure with Pd1/TiO2.

Characterization

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns were recorded by using a Philips X’Pert Pro Super X-ray diffractometer with Cu–Kα radiation (λ = 1.54178 Å). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were taken on a Hitachi Model H-7700 microscope at 100 kV. High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images were taken on a JEOL JEM-2100 field-emission higher-resolution transmission electron microscope at 200 kV. The aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM images and corresponding EDS mapping profiles were measured on the JEOL ARM-200F field-emission transmission electron microscope operated at 200 kV. UV-Vis diffuse reflectance data were recorded in the spectral region of 200–800 nm with a Shimadzu SolidSpec-3700 spectrophotometer. The X-ray adsorption fine structure (XAFS) spectra of sample were acquired at beamline 1W1B of the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF) and beamline 14W1 of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF). For XANES spectra, the experimental absorption coefficients as a function of energies were processed by background subtraction and normalization procedures and reported as the normalized intensity. The acquired EXAFS data were processed according to the standard procedure using the WinXAS3.1 program. The in situ NAP-XPS measurements were carried at the beamline BL02B1 of SSRF under light irradiation (365 nm LED light) or dark condition. In situ EPR spectra for oxygen vacancies detection are obtained on the JEOL JES-FA200 spectrometer equipped with a 500 W xenon lamp as the illumination source.

Detection of methyl radical (∙CH3)

5, 5'-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) was used to trap the generated methyl or hydroxyl radicals in the reaction system. Briefly, the as-prepared catalysts and DMPO are dispersed in ice-bath DI water. The mixture was vigorously shaken for 10 s and irradiated under 0.1 MPa CH4 by using a 500 W xenon lamp, and then analyzed by EPR spectroscopy.

DRIFTS for CO adsorption

DRIFTS measurements were performed using a Bruker IFS 66 v Fourier-transform spectrometer equipped with Harrick diffuse reflectance accessory with ZnSe and quartz window at BL01B in the National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (NSRL) in Hefei, China. After the sample was loaded into the reaction chamber, pure Ar (99.999%) was purged into the chamber firstly for background spectra collection. Subsequently, CO was introduced into the system until CO adsorbed saturation. Then the pure Ar was purged to remove the gaseous CO and the spectra were collected by averaging 128 scans at a resolution of 2 cm–1.

In situ DRIFTS for CH4 activation

In situ DRIFTS measurements were performed using a Bruker IFS 66 v Fourier-transform spectrometer equipped with Harrick diffuse reflectance accessory with ZnSe and quartz window at BL01B in the NSRL in Hefei, China. Each spectrum is recorded by averaging 128 scans at a resolution of 2 cm–1. After sample loading, the pure Ar was purged into the chamber for background spectra collection. Subsequently, pure CH4 (99.999%) is introduced into the chamber for 10 min. For CH4-adsorption process, the spectra were collected under dark condition at 5, 10, 20, and 30 min, respectively. After that, the system was exposed to light irradiation and the spectra were collected when the irradiation times are 1, 5, 10, 20, and 30 min, respectively.

Photocatalytic CH4 conversion measurements

The photocatalytic CH4 conversion experiments were carried out in CH4 atmosphere (0.1 MPa) at room temperature in a 30 mL custom-made quartz tube reactor. In a typical test, 3.0 mg of catalyst is dispersed in 800 μL of DI water and then dropped onto a 1 × 3 cm clear glass and dried in air at 323 K. After the glass was vertically placed in the reactor, 1 vol %, 10 vol % CH4/Ar or pure CH4 was purged into the system. The reactor was irradiated by a 300 W xenon lamp (PLS-SXE300, Perfect light). The produced H2 and hydrocarbons were quantified by a gas chromatograph (GC, 7890B, Ar carrier, Agilent) equipped with thermal conductivity detector (TCD) and flame ionization detector (FID). Another GC (Techcomp GC-7900, China) equipped with a TDX-01 packed column was employed to determine the amounts of CO and CO2. The isotope-labeled experiments were performed by using pure 13CH4, 12CH4, or CD4 as feeding gas. The products were analyzed with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS, 7890 A and 5975 C, He carrier, Agilent). For the regeneration treatment, the catalyst was heated under 80 °C for 2 h in air.

Determination of AQE for C2H6 production

The AQE was obtained by using different monochromatic filters (350, 380, 400, 450, 500, and 600 nm) during light irradiation. The irradiance values in ultraviolet region were measured by an UV energy meter (UV DESIGN, UV-int 140). The AQE was calculated through the following equation:

where Ne and Np represent the number of reacted electrons and incident photons, respectively, n is the number of electrons transferred during C2H6 formation, M is the molar number of C2H6, NA is the Avogadro’s constant, and W, S, t, h, and v are the light intensity, irradiation area, irradiation time, Planck constant and light frequency, respectively.

Photocurrent measurements

The photoelectrochemical measurements were performed on CHI 660E electrochemical workstation (CH Instruments) in three-electrode system under light irradiation. In all, 3.0 mg of catalyst was dispersed in 800 μL of DI water and then dropped onto a 1 × 3 cm fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO)-coated glass for employed as work electrode. The Pt foil and saturated Ag/AgCl electrode were used as counter electrode and reference electrode, respectively. 0.5 M Na2SO4 aqueous solution was chosen as the electrolyte. The electrolyte was saturated with pure Ar or CH4 prior before the tests. The photocurrent responses of the prepared photoelectrodes (i.e., I–t) were operated by measuring the photocurrent densities under chopped light irradiation (light on/off cycles: 50 s) at a bias potential of 0.8 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 800 s.

Calculation of carbon balance

Carbon balance was calculated through the following equation:

Computational method

The spin-polarized density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed by using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)50,51. The interaction between the core and valence electrons was described using the frozen-core projector augmented wave (PAW) approach52,53. The generalized gradient approximation of Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional was used54. The energy cutoff was set to be 400 eV. The DFT-D2 vdW correction proposed by Grimme was adopted to describe long-range vdW interactions55. The convergence criteria of energy and force were set to be 10−5 eV and 0.02 eV Å−1, respectively. A Monkhorst–Pack grid of 9 × 9 × 3 k-points was used to sample the Brillouin zone of the unit cell for the anatase TiO2. The optimized lattice parameters were a = b = 3.789 Å and c = 9.479 Å. A 3 × 3 supercell with five layers of TiO2 was used to describe the (001) surface. The bottom layer Ti and O dangling bonds were saturated with pseudo-hydrogens with nuclear charges of +1.25 and +0.75, which has been reported in previous studies56,57. A vacuum space greater than 15 Å perpendicular to the surface was applied to separate the interactions between neighboring slabs. The Brillouin zone was sampled by the 1 × 1 × 1 Γ-centered k-point for the slab system.

The energy differences (ΔE) for the reactions were calculated according to the approach originally proposed by Nørskov and coworkers58,59, ΔE = ΔE0 + ΔEU, where ΔE0 is the computed reaction energy. The external potential supplied by photogenerated holes was added by ΔEU = −eUh, where Uh is the electrode potential relative to the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE). The transition states were searched with the nudged elastic band method with climbing images60.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article and its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Saha, D., Grappe, H. A., Chakraborty, A. & Orkoulas, G. Postextraction separation, on-board storage, and catalytic conversion of methane in natural gas: a review. Chem. Rev. 116, 11436–11499 (2016).

Kiani, D. et al. Methane activation by ZSM-5-supported transition metal centers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 1251–1268 (2021).

Schwach, P., Pan, X. & Bao, X. Direct conversion of methane to value-added chemicals over heterogeneous catalysts: challenges and prospects. Chem. Rev. 117, 8497–8520 (2017).

Farrell, B. L., Igenegbai, V. O. & Linic, S. A viewpoint on direct methane conversion to ethane and ethylene using oxidative coupling on solid catalysts. ACS Catal. 6, 4340–4346 (2016).

Tang, P., Zhu, Q., Wu, Z. & Ma, D. Methane activation: the past and future. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 2580–2591 (2014).

Liu, Z. et al. Online kinetics study of oxidative coupling of methane over La2O3 for methane activation: what Is behind the distinguished light-off temperatures? ACS Catal. 8, 11761–11772 (2018).

Lei, Y., Chu, C., Li, S. & Sun, Y. Methane activations by lanthanum oxide clusters. J. Phys. Chem. C. 118, 7932–7945 (2014).

Jiang, W. et al. Pd-modified ZnO–Au enabling alkoxy intermediates formation and dehydrogenation for photocatalytic conversion of methane to ethylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 269–278 (2021).

Li, L. et al. Efficient sunlight-driven dehydrogenative coupling of methane to ethane over a Zn+-modified zeolite. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 8299–8303 (2011).

Wu, S. et al. Ga-doped and Pt-loaded porous TiO2–SiO2 for photocatalytic nonoxidative coupling of methane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 6592–6600 (2019).

Chen, Z. et al. Non-oxidative coupling of methane: N-type doping of niobium single atoms in TiO2–SiO2 induces electron localization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 11901–11909 (2021).

Lang, J. et al. Highly efficient light-driven methane coupling under ambient conditions based on an integrated design of a photocatalytic system. Green. Chem. 22, 4669–4675 (2020).

Zhang, Y.-Y. et al. Origin of the type-II band offset between rutile and anatase titanium dioxide: Classical and quantum-mechanical interactions between O ions. Phys. Rev. B 95, 155308 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Origin of photocatalytic activity of nitrogen-doped TiO2 nanobelts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 12290–12297 (2009).

Chen, X. et al. Photocatalytic oxidation of methane over silver decorated zinc oxide nanocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 7, 12273 (2016).

Hu, D., Ordomsky, V. V. & Khodakov, A. Y. Major routes in the photocatalytic methane conversion into chemicals and fuels under mild conditions. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 286, 119913 (2021).

Yu, X. et al. Selective photocatalytic conversion of methane into carbon monoxide over zinc-heteropolyacid-titania nanocomposites. Nat. Commun. 10, 700 (2019).

Yu, X. et al. Stoichiometric methane conversion to ethane using photochemical looping at ambient temperature. Nat. Energy 5, 511–519 (2020).

Gao, C. et al. Heterogeneous single-atom photocatalysts: fundamentals and applications. Chem. Rev. 120, 12175–12216 (2020).

Thomas, A. G. et al. Comparison of the electronic structure of anatase and rutile TiO2 single-crystal surfaces using resonant photoemission and x-ray absorption spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 75, 035105 (2007).

Mete, E., Gülseren, O. & Ellialtıoğlu, Ş. Modification of TiO2(001) surface electronic structure by Au impurity investigated with density functional theory. Phys. Rev. B 80, 035422 (2009).

Murugan, P., Kumar, V. & Kawazoe, Y. Thickness dependence of the atomic and electronic structures of TiO2 rutile (110) slabs and the effects on the electronic and magnetic properties of supported clusters of Pd and Rh. Phys. Rev. B 73, 075401 (2006).

Wan, J. et al. Defect effects on TiO2 nanosheets: stabilizing single atomic site Au and promoting catalytic properties. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705369 (2018).

Bai, S., Jiang, J., Zhang, Q. & Xiong, Y. Steering charge kinetics in photocatalysis: intersection of materials syntheses, characterization techniques and theoretical simulations. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 2893–2939 (2015).

Zhang, X. et al. C–C coupling on single-atom-based heterogeneous catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 954–962 (2018).

Liu, P. et al. Photochemical route for synthesizing atomically dispersed palladium catalysts. Science 352, 797 (2016).

Liu, P. et al. A vicinal effect for promoting catalysis of Pd1/TiO2: supports of atomically dispersed catalysts play more roles than simply serving as ligands. Sci. Bull. 63, 675–682 (2018).

Chin, Y.-H. & Iglesia, E. Elementary steps, the role of chemisorbed oxygen, and the effects of cluster size in catalytic CH4–O2 reactions on palladium. J. Phys. Chem. C. 115, 17845–17855 (2011).

Chin, Y.-H., Buda, C., Neurock, M. & Iglesia, E. Consequences of metal–oxide interconversion for C–H bond activation during CH4 reactions on Pd catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 15425–15442 (2013).

Song, H. et al. Direct and selective photocatalytic oxidation of CH4 to oxygenates with O2 on cocatalysts/ZnO at room temperature in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 20507–20515 (2019).

Bai, S. et al. High-efficiency direct methane conversion to oxygenates on a cerium dioxide nanowires supported rhodium single-atom catalyst. Nat. Commun. 11, 954 (2020).

Shen, Q. et al. Single chromium atoms supported on titanium dioxide nanoparticles for synergic catalytic methane conversion under mild conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 1216–1219 (2020).

Li, C. & Xin, Q. FT-IR spectroscopic investigation of methane adsorption on cerium oxide. J. Phys. Chem. 96, 7714–7718 (1992).

Finnie, K. S. et al. Vibrational spectroscopy and EXAFS study of Ti(OC2H5)4 and alcohol exchange in Ti(iso-OC3H7)4. J. Mater. Chem. 10, 409–418 (2000).

Tao, F. F. et al. Understanding complete oxidation of methane on spinel oxides at a molecular level. Nat. Commun. 6, 7798 (2015).

Yee, A., Morrison, S. J. & Idriss, H. A study of the reactions of ethanol on CeO2 and Pd/CeO2 by steady state reactions, temperature programmed desorption, and in situ FT-IR. J. Catal. 186, 279–295 (1999).

Mudiyanselage, K. et al. Importance of the metal–oxide interface in catalysis: in situ studies of the water–gas shift reaction by ambient-pressure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 5101–5105 (2013).

Liu, Z. et al. Water-promoted interfacial pathways in methane oxidation to methanol on a CeO2-Cu2O catalyst. Science 368, 513 (2020).

Zuo, Z. et al. Low-temperature conversion of methane to methanol on CeOx/Cu2O catalysts: water controlled activation of the C–H bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 13810–13813 (2016).

Lustemberg, P. G. et al. Direct conversion of methane to methanol on Ni-ceria surfaces: metal–support interactions and water-enabled catalytic conversion by site blocking. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 7681–7687 (2018).

Naldoni, A. et al. Photocatalysis with reduced TiO2: from black TiO2 to cocatalyst-free hydrogen production. ACS Catal. 9, 345–364 (2019).

Gan, Q. et al. Defect-assisted selective surface phosphorus doping to enhance rate capability of titanium dioxide for sodium ion batteries. ACS Nano 13, 9247–9258 (2019).

Ou, G. et al. Tuning defects in oxides at room temperature by lithium reduction. Nat. Commun. 9, 1302 (2018).

Saputera, W. H. et al. Light-induced synergistic multidefect sites on TiO2/SiO2 composites for catalytic dehydrogenation. ACS Catal. 9, 2674–2684 (2019).

Wang, G. et al. Light-induced nonoxidative coupling of methane using stable solid solutions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 20760–20764 (2021).

Belgued, M., Pareja, P., Amariglio, A. & Amariglio, H. Conversion of methane into higher hydrocarbons on platinum. Nature 352, 789–790 (1991).

Soulivong, D. et al. Non-oxidative coupling reaction of methane to ethane and hydrogen catalyzed by the silica-supported tantalum hydride: (≡SiO)2Ta−H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 5044–5045 (2008).

Xiao, Y. & Varma, A. Highly selective nonoxidative coupling of methane over Pt-Bi bimetallic catalysts. ACS Catal. 8, 2735–2740 (2018).

Dipu, A. L. et al. Direct nonoxidative conversion of methane to higher hydrocarbons over silica-supported nickel phosphide catalyst. ACS Catal. 10, 375–379 (2020).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev., Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1787–1799 (2006).

Chu, W. et al. Ultrafast dynamics of photongenerated holes at a CH3OH/TiO2 rutile interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 13740–13749 (2016).

Chu, W., Zheng, Q., Prezhdo, O. V. & Zhao, J. CO2 photoreduction on metal oxide surface is driven by transient capture of hot electrons: ab initio quantum dynamics simulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 3214–3221 (2020).

Nørskov, J. K. et al. Origin of the overpotential for oxygen reduction at a fuel-cell cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 17886–17892 (2004).

Howalt, J. G., Bligaard, T., Rossmeisl, J. & Vegge, T. DFT based study of transition metal nano-clusters for electrochemical NH3 production. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 7785–7795 (2013).

Henkelman, G. & Jónsson, H. Improved tangent estimate in the nudged elastic band method for finding minimum energy paths and saddle points. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9978–9985 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported in part by the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFA0207301), NSFC (21725102, 22122506, 91961106, 22075267, 21688102, and 22073085), Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2008085J05 and 2008085QB71), Youth Innovation Promotion Association of CAS (2019444), DNL Cooperation Fund, CAS (DNL201922) and Users with Excellence Program of Hefei Science Center CAS (2020HSC-UE003). The in situ DRIFTS measurements were performed at beamline BL01B in the NSRL. NAP-XPS measurements were performed at the beamline BL02B1 of SSRF supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under contract no. 11227902. XAFS measurements were performed at the beamline 1W1B of the BSRF and beamline BL14W1 of SSRF. The authors thank the support from USTC Center for Micro- and Nanoscale Research and Fabrication. The numerical calculations were performed on the supercomputing system in the USTC-SCC and CAS-SCC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Z., R.L., and Y.X. conceived the idea for this work. W.Z. prepared the photocatalysts and performed the characterizations, catalytic measurements, and in situ experiments. C.F. and J.Y. carried out the DFT calculations. W.Z., J.M., Y.C., X.L., H.Z., and Z.L. contributed to the NAP-XPS measurements. W.Z., J.L., R.L., Y.Y., Z.Z., and Y.X. analyzed the data. D.D. conducted the XAS measurements. H.L. and Z.Q. contributed to the DRIFTS measurements. W.Z., C.F., J.L., R.L., Y.Y., and Y.X. wrote the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the interpretation of the data and the preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A patent application was submitted to China National Intellectual Property Administration (patent applicant: University of Science and Technology of China; names of inventors: Yujie Xiong, Wenqing Zhang, Ran Long; application number: 202111469224.3; status of application: submitted; specific aspect of manuscript covered in the patent application: the preparation of single-atom Pd-TiO2 catalysts, and their photocatalytic nonoxidative conversion of methane to ethane). Other than this, the authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Vitaly Ordomsky and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, W., Fu, C., Low, J. et al. High-performance photocatalytic nonoxidative conversion of methane to ethane and hydrogen by heteroatoms-engineered TiO2. Nat Commun 13, 2806 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30532-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30532-z

This article is cited by

-

Photocatalytic ethylene production by oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane with dioxygen on ZnO-supported PdZn intermetallic nanoparticles

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Efficient hole abstraction for highly selective oxidative coupling of methane by Au-sputtered TiO2 photocatalysts

Nature Energy (2023)

-

High-density frustrated Lewis pairs based on Lamellar Nb2O5 for photocatalytic non-oxidative methane coupling

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Light-driven flow synthesis of acetic acid from methane with chemical looping

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Internal quantum efficiency higher than 100% achieved by combining doping and quantum effects for photocatalytic overall water splitting

Nature Energy (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.