Abstract

Giant spin-orbit torque (SOT) from topological insulators (TIs) provides an energy efficient writing method for magnetic memory, which, however, is still premature for practical applications due to the challenge of the integration with magnetic tunnel junctions (MTJs). Here, we demonstrate a functional TI-MTJ device that could become the core element of the future energy-efficient spintronic devices, such as SOT-based magnetic random-access memory (SOT-MRAM). The state-of-the-art tunneling magnetoresistance (TMR) ratio of 102% and the ultralow switching current density of 1.2 × 105 A cm−2 have been simultaneously achieved in the TI-MTJ device at room temperature, laying down the foundation for TI-driven SOT-MRAM. The charge-spin conversion efficiency θSH in TIs is quantified by both the SOT-induced shift of the magnetic switching field (θSH = 1.59) and the SOT-induced ferromagnetic resonance (ST-FMR) (θSH = 1.02), which is one order of magnitude larger than that in conventional heavy metals. These results inspire a revolution of SOT-MRAM from classical to quantum materials, with great potential to further reduce the energy consumption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-volatile magnetic memory is a promising candidate for next-generation memory technology beyond complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS). Such magnetic random-access memory (MRAM)1,2, has ultralow energy consumption (~fJ), ultrafast speed (~ns) and almost infinite endurance (1015 cycles). The information of MRAM is stored in the magnetic tunnel junction (MTJ) of a ferromagnetic electrode/insulator/ferromagnetic electrode (FM/I/FM) structure, where the tunneling resistance strongly depends on the magnetization orientations of two FM electrodes, and thus the information of “0” and “1” can be stored in the parallel and antiparallel magnetization states, respectively3,4,5,6,7,8. Besides the magnetic field, current-induced spin torques such as spin-transfer torque (STT) and spin-orbit torque (SOT) can be used to provide an efficient switching mechanism of the magnetization9,10,11,12.

In particular, SOT-driven magnetization switching has been demonstrated in heavy metal/ferromagnet (HM/FM) based structures, where the spin current generated by the strong spin-orbit coupling in HMs exerts a spin torque to the adjacent FM and thus switches the magnetization with a current (typically with a density around 107 A cm−2)11,12,13,14,15. Compared to the 2-terminal STT-MRAM in which the writing current flows vertically through the MTJ stack, in the 3-terminal SOT-MRAM, the writing current only flows transversely in a separate bottom electrode, and thus the electromigration resulting damage to the tunneling barrier can be minimized, which dramatically increases the endurance of MRAM16,17,18,19,20,21.

Reducing the energy consumption is a major challenge for SOT-MRAM. Quantum materials such as topological insulators (TIs) inspire a promising route to overcome the limitation of charge-spin conversion efficiency θSH = Js /Je < 1 in classical materials22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34, where Js and Je represent the spin current density and charge current density, respectively. In TIs, the topological surface states give rise to a large θSH due to the spin-momentum locking of the surface Dirac electrons, where the bulk is insulating in the ideal case25,27,35. A great interest has been focused on the SOT in TI/FM bilayer structures, in which θSH is found to be 1-2 orders of magnitude larger than that in HMs even at room temperature28,29,30,31,32,33. However, there is still a big challenge for integrating TIs with MTJs for SOT-MRAM applications: conventional SOT-MRAM is based on the current Si-based CMOS technology, whereas the single-crystal TI layer needs to be epitaxially grown on specific substrates (such as GaAs and Al2O3) by molecular beam epitaxy (MBE)36. Therefore, for TI-driven SOT-MRAM, the following issues need to be solved: How to control the interface between TIs and MTJs to achieve state-of-the-art tunneling magnetoresistance (TMR) ratio and at the same time preserve the topological surface states? How to reduce the element diffusion that damages the TI surface states during the annealing treatment for MTJ? How to avoid the chemical degradation of the TI crystal quality during the photolithography process of SOT devices?

In this article, we demonstrate a TI-driven SOT-MRAM cell with a state-of-the-art TMR ratio (over 100%) and an ultralow switching current density Jc (105 A cm−2) at room temperature, where the topological surface states contribute to the large charge-spin conversion (θSH > 1). Two types of SOT switching are demonstrated: the collinear spin polarization σ and easy axis (EA), for which can realize the field-free switching with lower Jc (1.2 × 105 A cm−2); the orthogonal σ and EA, which leads to a much faster switching speed. The charge-spin conversion efficiency θSH in TIs is quantified by two methods: the SOT-induced shift of the magnetic switching field and the SOT-induced ferromagnetic resonance (ST-FMR), which give rise to θSH = 1.59 and θSH = 1.02, respectively. At last, SOT switching is demonstrated in the all-sputtered TI-MTJ device for potential industry-level applications. This work demonstrates the SOT-MRAM cell driven by TIs with ultralow energy consumption.

Results and discussion

Device structure and magnetic properties

The full TI-MTJ stack consists of a sequence of layers: (BiSb)2Te3(10)/Ru(5)/CoFeB(2.5)/MgO(1.9)/CoFeB(5)/Ta(8)/Ru(7) (thickness in nanometers). The TI of (BiSb)2Te3 is epitaxially grown on the Al2O3(0001) substrate by the MBE method, where the layer-by-layer growth mode is monitored by the reflection high-energy electron diffraction (RHEED) patterns. Then, the (BiSb)2Te3 sample is transferred from the MBE chamber to the magnetron sputtering chamber to grow the MTJ stack of Ru(5)/CoFeB(2.5)/MgO(1.9)/CoFeB(5)/Ta(8)/Ru(7). The Ru interlayer is inserted to decouple the exchange interaction between (BiSb)2Te3 and CoFeB and block the element diffusion during annealing, which may destroy the topological surface states37,38. The TI-MTJ stack is patterned into the SOT devices by the photo and electron-beam lithography combined with the ion milling process. A 300 oC annealing process is performed to improve the crystal quality of the MgO barrier and the TMR ratio, during which an in-plane magnetic field (8 kOe) is applied to induce an in-plane magnetic easy axis (EA) for the top and bottom CoFeB (T-CoFeB and B-CoFeB) electrodes39,40.

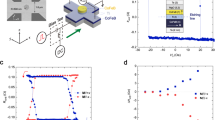

Figure 1a shows the helical Dirac-cone band structure of the topological surface states, where the spin-momentum locking gives rise the spin-polarized electron current. In the schematic of the 3-terminal SOT device of TI-MTJ, as shown in Fig. 1a, the writing current is applied between terminal 1 (T1) and T2, where the spin-polarized current in topological surface states is employed to provide the SOT and switch the magnetization of the free-layer (B-CoFeB) of the MTJ. For reading, a small vertical current between T1 and T3 is applied to pass through the tunneling barrier MgO, where the tunneling resistance strongly depends on the magnetization orientation between the free-layer (B-CoFeB) and the fixed-layer (T-CoFeB): low resistance for the parallel state (“0” state) and high resistance for the antiparallel state (“1” state), respectively, i.e., the TMR effect. From the cross-sectional scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) results, we see the layer-by-layer (i.e., van der Waals) structure of the TI [(BiSb)2Te3] and the clear interface between TI and MTJ.

a Schematic of the 3-terminal SOT-MRAM cell with a topological insulator (TI). The writing current applied between T1 and T2 is used to switch the magnetic tunnel junction (MTJ) between the parallel and antiparallel states by the spin-orbit torque (SOT), and the reading is done by the tunneling magnetoresistance (TMR) between T1 and T3. In the TI, the surface is conducting while the bulk is insulating, and the spin-momentum locking of the surface states provides a giant SOT. Cross-sectional scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) results show the layer-by-layer structure of the TI [(BiSb)2Te3] and the clear interface between TI and MTJ. b The two-step switching process in the M-H curves shows the different coercive fields of the bottom and top CoFeB layers in the MTJ stack. c Microscopic picture of the patterned SOT-MRAM device, where the TI layer serves as the bottom electrode, and the MTJ device on top is 2 μm × 6 μm in size. The scale bar is 20 μm. d Tunneling resistance R and TMR ratio as a function of the magnetic field, where the 102% TMR ratio indicates the high quality of MTJ.

The magnetic hysteresis (M-H) loop of the TI-MTJ stack is shown in Fig. 1b, where the magnetic field is scanned along the EA of the MTJ. The 2-step magnetization reversal process clearly shows the different coercive fields of T-CoFeB (Hc1 = 10 Oe) and B-CoFeB (Hc2 = 20 Oe), which supports an antiparallel state between Hc1 and Hc2. The microscopic picture of the patterned SOT device is shown in Fig. 1c, where the TI layer serves as the bottom electrode, and the MTJ stack of a 2 μm × 6 μm size is located at the intersection region between the bottom and top electrodes. Figure 1d shows the tunneling resistance R and the TMR ratio as a function of the magnetic field H at room temperature, where a TMR ratio of 102% indicates the high-quality of the MTJ on top of the TI surface.

Current-driven SOT switching

The current-driven SOT switching is performed in two types of configurations41: the collinear case between σ and EA (EA along y) and the orthogonal case (EA along x). A writing current pulse Je (1 ms) between T1 and T2 is applied to provide the SOT, followed by a small reading current pulse JR (10 μA, 1 ms) that passes through the MTJ between T1 and T3 to detect the magnetization at 1-s later.

For the collinear σ∥EA case (EA along y), as shown in Fig. 2a, the damping-like torque [\(-m\times (m\times \sigma )\)] breaks the mirror symmetry between +my and −my and thus efficiently switches the magnetization without the external magnetic field, i.e., field-free switching. Macrospin simulation results show the magnetization gradually precesses from +my to −my states, i.e., precessional switching mode, with a switching speed of 7.5 ns (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1b). Figure 2b shows the MTJ resistance as a function of the writing current density in the TI layer (R-Je) at room temperature, with a critical switching current density Jc of 1.2 × 105 A cm−2, which is 1-2 orders of magnitude lower than that in HM-based systems11,12,13,14,15.

a, b show the SOT switching for the collinear case between the spin polarization (σ) and the easy axis (σ∥EA). b The current-driven SOT switching shows the deterministic switching without external magnetic field, i.e., field-free switching, where the magnetic field Hz has not effect on the switching polarity. c, d show the SOT switching for the orthogonal case of σ⊥EA, where a Hz is needed for deterministic switching. d For the σ⊥EA case, an external magnetic field Hz is needed to break the mirror symmetry between +mx and −mx for deterministic SOT switching, as indicated by the opposite SOT switching polarities under Hz = ±100 Oe. e, SOT switching for the MTJ scaling down from 4 µm × 8 µm to 100 nm × 200 nm (σ∥EA).

For the orthogonal σ⊥EA case (EA along x), an external magnetic field Hz is needed to break the mirror symmetry between +mx and −mx for the deterministic switching41, as shown in Fig. 2c. For σ⊥EA, due to the polarity of the magnetization changes once the SOT is applied, the dynamic reversal mode produces a much shorter switching trajectory and a much faster switching speed of 1.0 ns (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1e). Figure 2d shows that Jc in the σ⊥EA case (4.1 × 105 A cm−2) is more than 3 times higher than that in the σ∥EA case (1.2 × 105 A cm−2). The opposite switching polarities at Hz = ±100 Oe indicate the standard SOT switching characteristic.

Only the partial SOT switching is achieved in large-size (µm) MTJs, because of the magnetic domain pining from the steps at the (BiSb)2Te3 surface induced by the layer-by-layer growth. In order to realize the full SOT switching, the size of MTJ is scaling down from 4 µm × 8 µm to 100 nm × 200 nm, as shown in Fig. 2e, and the results show that the SOT switching ratio increases with scaling down the MTJ, where the almost full SOT switching is achieved in 100 nm × 200 nm (switching ratio ΔTMR/TMR = 95%) and 150 nm × 300 nm (switching ratio 92%) MTJs. The MTJ size for full SOT switching is consistent with the crystal grain size (200~300 nm) of the (BiSb)2Te3 surface42.

SOT-induced shift of the magnetic switching field

The SOT-induced effective field HSOT is quantified by the shift of the magnetic switching field Hc2 of B-CoFeB in the R-Hy loops43, under a bias SOT current Je in the bottom electrode between T1 and T2, where EA is along the y axis, as shown in Fig. 3a. Due to the HSOT, the Hc2 is shifted to the opposite direction under ±Je, respectively, and the shift field Hc2shift = (Hc2+shift + Hc2−shift)/2 = HSOT( + Je) − HSOT( − Je) = 2 HSOT(Je), where Hc2+shift and Hc2−shift represent the shift of the positive and negative switching fields of B-CoFeB, respectively.

a R-Hy curves measured under the opposite bias SOT current ±Je between T1 and T2, where the shift of the magnetic switching field of B-CoFeB indicates the SOT-induced effective field Hc2shift = (Hc2+shift + Hc2−shift)/2 = HSOT(+Je) − HSOT(−Je) = 2HSOT(Je). b HSOT as a function of the bias SOT current Je, where the linear dependence shows the typical SOT characteristic.

The HSOT as a function of Je is plotted in Fig. 3b, and the linear dependence is consistent with the spin-momentum locking induced spin polarization in topological surface states. The SOT efficiency χSOT = HSOT/Je = 24.1 × 10−6 Oe A−1 cm2 is obtained by fitting the HSOT-Je curve, and thus contributes to a charge-spin conversion efficiency of \({\theta }_{SH}=(2|e|{M}_{s}{t}_{F}/\hslash )\times {\chi }_{SOT}=1.59\), where e is the electron charge, Ms is the saturation magnetization (1100 emu cm−3), tF is the magnetic film thickness (2.5 nm), and \(\hslash\) is the reduced Planck constant. The obtained value of θSH (1.59) here is consistent with that (θSH = 2.5) in (BiSb)2Te3/Ti/CoFeB/MgO system with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy by the 2nd harmonic measurement31. By considering the 2-dimentional (2D) current distribution in the TI surface, we can also obtain the interfacial charge-spin conversion efficiency \({q}_{{{{{{\rm{ICS}}}}}}}={J}_{{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}}/{J}_{{{{{{\rm{e}}}}}}}^{2{{{{{\rm{D}}}}}}}={\theta }_{{{{{{\rm{SH}}}}}}}/{t}_{{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}}=1.06\,{{{{{{\rm{nm}}}}}}}^{-1}\), where \({{J}_{{{{{{\rm{e}}}}}}}}^{{{{{{\rm{2D}}}}}}}\) represents the 2D electric current density, and ts represents the surface thickness of TI [1.5 nm for (BiSb)2Te3]31,44.

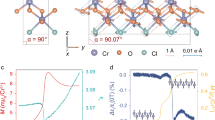

SOT-induced ferromagnetic resonance

The SOT-induced ferromagnetic resonance (ST-FMR)23,34,45 is also employed to quantify the charge-spin conversion efficiency in (BiSb)2Te3, with the structure of (BiSb)2Te3(10)/Ru(5)/CoFeB(2.5)/MgO(1.9), which is the same as the free layer in the TI-MTJ stack. As shown in the schematic of the ST-FMR measurement in Fig. 4a, a microwave current (12 dBm) is applied to excite the magnetic resonance, where an in-plane magnetic field H is scanned with a fixed angle θ = 45°. The microwave is modulated by the lock-in amplifier with a 20 kHz frequency. The damping-like torque τDL and the field-like torque τFL originate from the SOT and the Oersted field of the ac current, respectively. Figure 4b shows the magnetic resonant frequency f as the function of the magnetic field H, which can be fitted well by the standard Kittel equation \({f}=\frac{\gamma} {2{{{{{\rm{\pi}}}}}}}\sqrt{H_{{{{{\rm{res}}}}}} ({H}_{{{{{\rm{res}}}}}} +4{{{{{{\rm{\pi}}}}}}}{M}_{{{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}}})}\) with an effective in-plane magnetization 4πMeff ~ 1.19 T.

a Schematic of the SOT-induced FMR measurement. A microwave current is applied to excite the magnetic resonance, and an applied in-plane magnetic field H with θ = 45° is scanned during the measurement. The damping-like torque τDL is dominated by the SOT, where the field-like torque τFL mainly comes from the Oersted field. b Resonance frequency f as a function of the magnetic field H, which can be fitted by the Kittel equation. c The Vmix-H curve can be fitted by Eq. (1), where the SOT and Oersted field contributions can be obtained by the symmetric and antisymmetric parts, respectively. d The charge-spin conversion efficiency θSH is almost independent with the frequency from 5 to 8 GHz. The error bar comes from the fitting process in Fig. 4c.

During the magnetization precession, the mixing of the oscillation magnetoresistance and the ac current produces a dc voltage Vmix, as shown in the Fig. 4c, which can be fitted by \({V}_{{{{{\rm{mix}}}}}}=S\frac{{\triangle}^{2}}{{\triangle}^{2}{+}{({H}_{{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}}-{H}_{{{{{\rm{res}}}}}})}^{2}}{+}A\frac{\triangle ({H}_{{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}}-{H}_{{{{{\rm{res}}}}}})}{{\triangle }^{2}{+}{({H}_{{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}}-{H}_{{{{{\rm{res}}}}}})}^{2}}\), where Δ is the linewidth, Hres is the resonant magnetic field, S and A represents the coefficient of symmetric part and antisymmetric part, respectively. The symmetric part S is attributed to the SOT (τDL) from (BiSb)2Te3, which is proportional to the current density JTI; on the other hand, the antisymmetric part A comes from the Oersted field contribution (τFL), which is dominated by the current density JRu in the Ru layer. The charge-spin conversion efficiency θSH could be expressed as:

where tRu and tCoFeB represent the thickness of Ru and CoFeB, respectively. After subtracting the spin pumping contribution (27% of the symmetric part, Supplementary Note 6), the obtained θSH by ST-FMR for f = 5-8 GHz is shown in the Fig. 4d, and the θSH is almost constant at different frequencies, with the average value of 1.02 (qICS = 0.68 nm−1), which is consistent with θSH = 1.59 (qICS = 1.06 nm−1) from the SOT-induced switching field shift in the TI-MTJ device.

All sputtered BiSb-MTJ device

In order to be compatible with the industry-level manufacture, the topological insulator of BiSb is prepared by the magnetron sputtering method29,46, and the MTJ stack of Ru(5)/CoFeB(2.5)/MgO(2)/CoFeB(5)/Ta(8)/Ru(7) is in-situ deposited on top of the sputtered BiSb(10) without breaking the vacuum (thickness in nanometers), i.e., all sputtered BiSb-MTJ. The TMR ratio of the all sputtered BiSb-MTJ is around 90%, as shown in Fig. 5a. The current-induced SOT can efficiently switch the bottom CoFeB layer and thus the resistance state of MTJ at room temperature, with a critical switching current density Jc of 1.4 × 106 A cm−2, as shown in Fig. 5b. Even Jc for the sputtered BiSb is 1 order of magnitude higher than the MBE-grown (BiSb)2Te3, the high conductivity of the sputtered BiSb (1.8 × 105 Ω−1 m−1) could help to reduce the Ohmic loss, especially from the shunting effect.

In conclusion, the SOT-MRAM cell is demonstrated in a TI-MTJ device with over 100% TMR ratio, where the energy consumption is significantly reduced due to the ultralow switching current density of 105 A cm−2. The >1 charge-spin conversion efficiency (θSH) in (BiSb)2Te3 is quantified by the SOT-induced switching field shift and the ST-FMR measurements at room temperature, which breaks down the limitation of θSH < 1 in classical material systems. This work paves a path for the application of TI-driven magnetic memory, and potentially inspires the revolution of current magnetic memory technology from classical to quantum materials.

Methods

Sample growth and device fabrication

The high-quality (Bi0.2Sb0.8)2Te3 films were grown on Al2O3(0001) substrates by using a Perkin Elmer MBE system in ultrahigh vacuum. Before the growth, the substrate was pre-annealed in the vacuum chamber at up to 700 °C to clean the surface. High-purity Bi (99.9999%), Te (99.9999%) and Sb (99.999%) were co-evaporated by conventional effusion cells and cracker cells. During the TI growth, the substrate was maintained at 200 °C, where the Bi, Sb and Te cells were kept at 457 °C, 387 °C and 340 °C, respectively. The layer-by-layer epitaxial growth was monitored by the in-situ reflection high-energy electron diffraction (RHEED).

The MTJ stacks of Ru (5 nm)/CoFeB (2.5 nm)/MgO (1.9 nm)/CoFeB (5 nm)/Ta (8 nm)/Ru (7 nm) were deposited by using a Singulus ROTARIS magnetron sputtering system at room temperature with a base pressure of 1 × 10−6 Pa. The CoFeB denotes Co40Fe40B20 alloy with nominal target compositions. When depositing the CoFeB ferromagnetic layers, a magnetic field of 50 Oe was applied to induce the magnetic easy axis. The MTJ devices with a rectangular shape were fabricated by using two photolithography, one electron-beam lithography and two Ar ion milling steps. To avoid the chemical degradation of the TI films caused by the developer, a poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) layer with a thickness of 300 nm was spin-coated on top of the film before the photolithography step, and then removed by O2 plasma before the Ar ion milling step. Subsequently, the final patterned MTJ devices were annealed in the vacuum at 300 °C for 1 h with a magnetic field of 8 kOe.

Magnetic and spin transport measurements

The SOT switching in the 3-terminal TI-MTJ device was measured by the probe station system with an electromagnet, where the pulse current was applied by the Keithley 2612 current source, and the voltage through the MTJ was measured by a Keithley 2182 A voltmeter. For the ST-FMR measurement, a signal generator was used to apply the microwave current with a nominal power of 12 dBm, where a lock-in amplifier (Stanford Research SR-830) was used to measure the voltage. In order to improve the signal-to-noise ratio, the microwave current was modulated by a sine function from the lock-in amplifier with 20 kHz. The magnetic properties of the TI-MTJ stack were measured by a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) system. All measurements were performed at room temperature.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Apalkov, D., Dieny, B. & Slaughter, J. M. Magnetoresistive random access memory. Proc. IEEE 104, 1796–1830 (2016).

Bhatti, S. et al. Spintronics based random access memory: a review. Mater. Today 20, 530–548 (2017).

Julliere, M. Tunneling between ferromagnetic films. Phys. Lett. A 54, 225–226 (1975).

Miyazaki, T. & Tezuka, N. Giant magnetic tunneling effect in Fe/Al2O3/Fe junction. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 139, L231–L234 (1995).

Moodera, J. S., Kinder, L. R., Wong, T. M. & Meservey, R. Large magnetoresistance at room temperature in ferromagnetic thin Film tunnel junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 3273–3276 (1995).

Butler, W. H., Zhang, X. G., Schulthess, T. C. & MacLaren, J. M. Spin-dependent tunneling conductance of Fe|MgO|Fe sandwiches. Phys. Rev. B 63, 54416 (2001).

Yuasa, S., Nagahama, T., Fukushima, A., Suzuki, Y. & Ando, K. Giant room-temperature magnetoresistance in single-crystal Fe/MgO/Fe magnetic tunnel junctions. Nat. Mater. 3, 868–871 (2004).

Parkin, S. S. P. et al. Giant tunnelling magnetoresistance at room temperature with MgO (100) tunnel barriers. Nat. Mater. 3, 862–867 (2004).

Slonczewski, J. C. Current-driven excitation of magnetic multilayers. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 159, L1–L7 (1996).

Ralph, D. C. & Stiles, M. D. Spin transfer torques. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 320, 1190–1216 (2008).

Miron, I. M. et al. Perpendicular switching of a single ferromagnetic layer induced by in-plane current injection. Nature 476, 189–193 (2011).

Liu, L. et al. Spin-torque switching with the giant spin Hall effect of tantalum. Science 336, 555–558 (2012).

Ryu, J., Lee, S., Lee, K.-J. & Park, B.-G. Current-induced spin–orbit torques for spintronic applications. Adv. Mater. 32, 1907148 (2020).

Yu, G. et al. Switching of perpendicular magnetization by spin–orbit torques in the absence of external magnetic fields. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 548–554 (2014).

Manchon, A. et al. Current-induced spin-orbit torques in ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 035004 (2019).

Rahaman, S. Z. et al. Size-dependent switching properties of spin-orbit torque MRAM with manufacturing-friendly 8-inch wafer-level uniformity. IEEE J. Electron Devices Soc. 8, 163–169 (2020).

Sato, N., Xue, F., White, R. M., Bi, C. & Wang, S. X. Two-terminal spin–orbit torque magnetoresistive random access memory. Nat. Electron. 1, 508–511 (2018).

Wang, M. et al. Field-free switching of a perpendicular magnetic tunnel junction through the interplay of spin–orbit and spin-transfer torques. Nat. Electron. 1, 582–588 (2018).

Nguyen, M.-H. et al. Efficient switching of 3-terminal magnetic tunnel junctions by the giant spin Hall effect of Pt85Hf15 alloy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 062404 (2018).

Rahaman, S. Z. et al. Pulse-width and temperature effect on the switching behavior of an etch-stop-on-MgO-barrier spin-orbit torque MRAM cell. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 39, 1306–1309 (2018).

Kong, W. J. et al. All-electrical manipulation of magnetization in magnetic tunnel junction via spin–orbit torque. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 162401 (2020).

Fan, Y. et al. Magnetization switching through giant spin–orbit torque in a magnetically doped topological insulator heterostructure. Nat. Mater. 13, 699–704 (2014).

Mellnik, A. R. et al. Spin-transfer torque generated by a topological insulator. Nature 511, 449–451 (2014).

Yasuda, K. et al. Current-nonlinear Hall effect and spin-orbit torque magnetization switching in a magnetic topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 137204 (2017).

Fan, Y. et al. Electric-field control of spin–orbit torque in a magnetically doped topological insulator. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 352–359 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Magnetization switching by magnon-mediated spin torque through an antiferromagnetic insulator. Science 366, 1125–1128 (2019).

Che, X. et al. Strongly surface state carrier-dependent spin–orbit torque in magnetic topological insulators. Adv. Mater. 32, 1907661 (2020).

Han, J. et al. Room-temperature spin-orbit torque switching induced by a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 077702 (2017).

Dc, M. et al. Room-temperature high spin–orbit torque due to quantum confinement in sputtered BixSe(1–x) films. Nat. Mater. 17, 800–807 (2018).

Khang, N. H. D., Ueda, Y. & Hai, P. N. A conductive topological insulator with large spin Hall effect for ultralow power spin–orbit torque switching. Nat. Mater. 17, 808–813 (2018).

Wu, H. et al. Room-temperature spin-orbit torque from topological surface states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 207205 (2019).

Wu, H. et al. Spin-orbit torque switching of a nearly compensated ferrimagnet by topological surface states. Adv. Mater. 31, 1901681 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Room temperature magnetization switching in topological insulator-ferromagnet heterostructures by spin-orbit torques. Nat. Commun. 8, 1364 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Topological surface states originated spin-orbit torques in Bi2Se3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 257202 (2015).

Tang, P., Han, X. & Zhang, S. Spin transport and dynamic properties of two-dimensional spin-momentum locked states. Europhys. Lett. 130, 58001 (2020).

Pai, C.-F. Switching by topological insulators. Nat. Mater. 17, 755–757 (2018).

Wray, L. A. et al. A topological insulator surface under strong Coulomb, magnetic and disorder perturbations. Nat. Phys. 7, 32–37 (2011).

Zhang, J., Velev, J. P., Dang, X. & Tsymbal, E. Y. Band structure and spin texture of Bi2Se3 3d ferromagnetic metal interface. Phys. Rev. B 94, 014435 (2016).

Chen, A. et al. Giant nonvolatile manipulation of magnetoresistance in magnetic tunnel junctions by electric fields via magnetoelectric coupling. Nat. Commun. 10, 243 (2019).

Chen, A. et al. Full voltage manipulation of the resistance of a magnetic tunnel junction. Sci. Adv. 5, eaay5141 (2019).

Fukami, S., Anekawa, T., Zhang, C. & Ohno, H. A spin–orbit torque switching scheme with collinear magnetic easy axis and current configuration. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 621–625 (2016).

Wu, H. et al. Ferrimagnetic skyrmions in topological insulator/ferrimagnet heterostructures. Adv. Mater. 32, 2003380 (2020).

Liu, Y.-T. et al. Determination of spin-orbit-torque efficiencies in heterostructures with in-plane magnetic anisotropy. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 044032 (2020).

Park, K., Heremans, J. J., Scarola, V. W. & Minic, D. Robustness of topologically protected surface states in layering of Bi2Te3 thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 186801 (2010).

Liu, L., Moriyama, T., Ralph, D. C. & Buhrman, R. A. Spin-torque ferromagnetic resonance induced by the spin Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 036601 (2011).

Khang, N. H. D., Nakano, S., Shirokura, T., Miyamoto, Y. & Hai, P. N. Ultralow power spin–orbit torque magnetization switching induced by a non-epitaxial topological insulator on Si substrates. Sci. Rep. 10, 12185 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NSF Award Nos. 1935362, 1909416, 1810163 and 1611570, the Nanosystems Engineering Research Center for Translational Applications of Nanoscale Multiferroic Systems (TANMS), the U.S. Army Research Office MURI program under Grants No. W911NF-16-1-0472 and No. W911NF-15-1-10561. The work at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) was supported by KAUST Office of Sponsored Research (OSR) under award No. CRF-2017-3427-CRG6. The work at Tokyo Tech. was supported by the CREST program (No. JPMJCR18T5) of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), and the Spintronics Research Network of Japan (Spin-RNJ). H.W. acknowledges the help of the schematic design from Chin-Chung Chen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.W. and K.L.W. conceived and supervised the project. P.Z., A.C., H.W. and X.Z. grew materials. A.C., H.W., B.F., Y.W., Y.M. and K.W. fabricated devices. H.W., P.Z., A.C. and S.A.R. performed magnetic and electrical transport measurements. H.H. and H.W. performed ST-FMR measurements. J.N., H.W. and G.P.C. performed macrospin and micromagnetic simulations. C.G., G.Y. and X.H. performed structural characterizations. J.S., T.S. and P.N.H. prepared the all-sputtered TI-MTJ. All authors contributed to discussions. H.W. and K.L.W. wrote the manuscript with the input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, H., Chen, A., Zhang, P. et al. Magnetic memory driven by topological insulators. Nat Commun 12, 6251 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26478-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26478-3

This article is cited by

-

Room temperature nonlocal detection of charge-spin interconversion in a topological insulator

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2024)

-

Spintronics intelligent devices

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2023)

-

Above-room-temperature strong intrinsic ferromagnetism in 2D van der Waals Fe3GaTe2 with large perpendicular magnetic anisotropy

Nature Communications (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.