Abstract

Metal nanoparticle (NP), cluster and isolated metal atom (or single atom, SA) exhibit different catalytic performance in heterogeneous catalysis originating from their distinct nanostructures. To maximize atom efficiency and boost activity for catalysis, the construction of structure–performance relationship provides an effective way at the atomic level. Here, we successfully fabricate fully exposed Pt3 clusters on the defective nanodiamond@graphene (ND@G) by the assistance of atomically dispersed Sn promoters, and correlated the n-butane direct dehydrogenation (DDH) activity with the average coordination number (CN) of Pt-Pt bond in Pt NP, Pt3 cluster and Pt SA for fundamentally understanding structure (especially the sub-nano structure) effects on n-butane DDH reaction at the atomic level. The as-prepared fully exposed Pt3 cluster catalyst shows higher conversion (35.4%) and remarkable alkene selectivity (99.0%) for n-butane direct DDH reaction at 450 °C, compared to typical Pt NP and Pt SA catalysts supported on ND@G. Density functional theory calculation (DFT) reveal that the fully exposed Pt3 clusters possess favorable dehydrogenation activation barrier of n-butane and reasonable desorption barrier of butene in the DDH reaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heterogeneous catalysis plays an indispensable role in chemical production1. For a typical supported metal catalyst, many factors including the crystallographic surface, chemical composition, particle size, and metal–support interaction can affect catalytic performances2. Recently, it has been found that well-dispersed nanoparticles (NPs), clusters, and isolated metal atoms (or single atoms, SAs) exhibited surprisingly different catalytic performances from bulk materials with the development of the advanced characterization tools and well-controlled synthesis technology, leading to the establishment of the structure–performance relationship at the atomic level3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11.

In several previous works, SAs catalysts exhibit advantages such as unique reaction pathway12, low adsorption energy of reactants/intermediate13 and maximal atom utilization4,14,15. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that clusters, though with inactive bulk components, were more active than SAs in some catalytic reactions. Anderson et al.16 deposited size-selected Aun+ (n = 1, 2, 3, 4, 7) on TiO2 support to study the relationship between Au size and CO oxidation activity. Owing to adverse CO-Au binding, Au or Au2 was inactive for CO oxidation. The activity was found in the order of Au7 > Au3 > Au4 > Au2 ≈ Au1. Corma et al.17,18 studied the size effect of different types of Pt species (single atoms, clusters, and nanoparticles) supported on various oxides. In the low-temperature NO reduction reaction with CO, the surface of Pt clusters favored NO dissociation and CO oxidation. The moderate adsorption of CO on Pt clusters could suppress catalyst poisoning, leading to higher activity than that of Pt SAs. Szanyi et al.19 found that Ru clusters favored CH4 formation in contrast to Ru single atoms. Due to the limited ability to activate hydrogen, single Ru atoms can only allow CO formation but cannot further hydrogenate it to CH4. However, we find later that the modulation of the chemical state of metal species by strong metal–support interaction is more important for observed selectivity regulation (metallic Ir particles for CH4 while partially oxidized Ir species for CO production) in CO2 hydrogenation reaction over Ir/CeO2 catalyst with different size of Ir species20. Nevertheless, the highly dispersed subnanometer-sized metal clusters (<1 nm) achieve maximum atomic exposure and utilization and possess various chemical coordination environments and chemical states that eventually affect the activity, selectivity, and stability of catalysts. It is the cluster with certain size, instead of single atoms, that was linked to high stability, selectivity, and activity in the heterogeneous catalysis, where the catalysts showed remarkable performance on structure-sensitive catalytic reactions21,22. But the small clusters always suffered from aggregating into metal NPs at high temperature, limiting their applications into high-temperature reactions23,24,25,26. Therefore, considering industrial application, designing thermodynamically stable metal cluster with low metal loading (especially noble metal) still remains highly desired.

Direct dehydrogenation (DDH) for light olefins production has been a thematic research area resulting from the energy shortage and petroleum gas upgrading scenario27,28. The primary catalyst designated for DDH is a Pt-based catalyst29,30. The side reactions of DDH including coke deposition, hydrogenolysis, and cracking are usually structure-sensitive, which prefer to occur on Pt NPs with large average Pt–Pt coordination numbers (CN)31. An ideal solution to suppress side reactions and promote catalytic performance is to downsize Pt NPs and regulate CN of Pt to a moderate level. In general, the addition of promoter metals to Pt afforded bimetallic and alloying systems, which can improve both the dispersion and stability for Pt species. For instance, as to n-butane dehydrogenation, Pt particle sizes decreased with increasing Sn loading in the PtSn/θ-Al2O3 catalyst. Higher atomic efficiency and the formation of PtSn alloying phases were correlated with higher activity and n-C42− selectivity. But the conversion rate remained low at each active site in such a large size PtSn alloying system32. Considering maximize atomic utilization, Pt/Cu single atom alloy catalyst is proposed in propane dehydrogenation. Compared with Pt NPs, isolated Pt atoms dispersed on copper nanoparticles dramatically enhance the propylene selectivity and stability33. Several bimetallic cluster catalysts have also been reported, including small raft-like PtSn clusters34, PtSn/ND@G35, Pt/Sn-Beta catalysts36, PtSn cluster37,38, and PtZn clusters defined in zeolites39,40, which displayed high activity for DDH reaction with excellent durability. But it also remains major challenges to synthesize clusters with precisely controlled metal-metal coordination numbers, and fundamentally understand the structure effects (SA, cluster and nanoparticle) on dehydrogenation performance at atomic level.

In this paper, we fabricated fully exposed Pt3 clusters stabilized on the defective graphene through Pt–C bond, with the geometric partitioning by the atomically dispersed Sn promoter, which can precisely tune the CN of supported Pt clusters based our previous reported methods35. The obtained Pt3 clusters with 0.5 wt% Pt loading showed higher conversion for n-butane DDH than Pt NPs and Pt SAs supported on ND@G. At a relatively low temperature (450 °C), n-butane rate of Pt3 clusters has achieved 1.138 mol·gPt−1·h−1. Moreover, we systemically established the structure–performance relationship by correlating the DDH activity with the average CN of Pt–Pt bond on ND@G supported Pt NP, Pt cluster, and Pt SA catalysts. By density functional theory (DFT) calculations, we found that the Pt3 cluster catalyst’s unique structure facilitates the activation of C–H bond and the desorption of butene. Such a structure–performance relationship may provide an insight for rationally designing highly active heterogeneous DDH catalysts in atomic scale.

Results

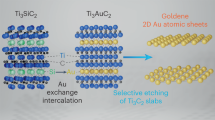

Construction of Pt3 clusters by the assistance of Sn

In order to fabricate ND@G supported Pt3 cluster catalysts, a serial of PtSn/ND@G catalysts were prepared by the co-impregnation method, denoted as Pt0.8Sn/ND@G (Sn/Pt atomic ratio = 0.85), Pt1.7Sn/ND@G (Sn/Pt atomic ratio = 1.7), Pt3.4Sn/ND@G (Sn/Pt atomic ratio = 3.4), and Pt6.8Sn/ND@G (Sn/Pt atomic ratio = 6.8). The Pt and Sn precursors anchored on the ND@G support composed of a diamond core and a defect-rich graphene shell (see the TEM images in Supplementary Fig. 1). The detailed structure and morphology of ND@G has been described in our previous reports12,35,41. The reference Pt/ND@G catalyst without the addition of any Sn was prepared by the same procedure. To elucidate the detailed structure of as-prepared PtSn catalysts, the study by aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) was carried out. Due to the difference in Z-contrast, the supported Pt species can be easily distinguished from Sn atoms, as shown in Fig. 1. As a control, the obtained Pt NPs of Pt/ND@G (nanoparticle diameter, d = 2.81 ± 0.95 nm) were located on the ND@G surface (Supplementary Fig. 2a-f), and the lattice fringes of the Pt NPs were apparent, implying the good crystallinity of the as-prepared Pt NPs on ND@G. The lattice spacing of Pt NPs is 0.23 nm, corresponding to the (111) facet of typical Pt NPs. Notably, with the addition of 0.25 wt% Sn, the well-dispersed Pt species, as nanoparticles with d = 1.43 ± 0.33 nm, were observed in Pt0.8Sn/ND@G (Supplementary Fig. 2g-i). The atomically dispersed Sn highlighted by green circles were located around the small Pt NPs (Supplementary Fig. 2i), suggesting that the presence of Sn can dramatically promote the dispersion of Pt NPs. For Pt1.7Sn/ND@G, the uniformly dispersed Pt clusters highlighted by red circles were found as closely connected “islands” on the ND@G support, surrounded by atomically dispersed Sn species in Fig. 1a-e. The extracted line profile shows that the Pt clusters were monolayered (Fig. 1f). It suggested that no Pt atoms covering each other and all Pt atoms were fully exposed35. Interestingly, as to the Pt3.4Sn/ND@G and Pt6.8Sn/ND@G catalysts, with the further addition of Sn, Pt atoms remained highly dispersed as irregular-shape tiny Pt clusters. Multiple adjacent Pt clusters aggregated into “islands”, which could be clearly resolved on the ND@G support (Fig. 1g–k and m–q). The extracted line profile showed that Pt clusters remained one-atomic-layer thick (Fig. 1l and r). However, high-density atomically dispersed Sn species were observed around the Pt clusters, resulting from larger loading amounts of Sn. These results indicate that the size and structure of Pt species are related to the geometric partitioning effect of Sn atoms, indicating that mono-dispersed Sn species facilitate the formation of atomically dispersed Pt clusters. When the atomic ratio Sn/Pt was greater than 1.7, almost all Pt atoms existed in the form of atomically dispersed Pt clusters.

a–e HAADF-STEM images of Pt1.7Sn/ND@G. g–k HAADF-STEM images of Pt3.4Sn/ND@G. m–q HAADF-STEM images of Pt6.8Sn/ND@G. In the images, Pt clusters are highlighted by the red circles, and atomically dispersed Sn atoms are highlighted by the green circles. f, l, r are the extracted line profiles along red directions in e, k, q, demonstrating the pronounced intensity difference between Pt and Sn, consistent well with their distinct atomic numbers (Z), together with the single-atomic-layer thickness of a typical Pt cluster. Scale bars: a, g, m, 5 nm; b–e, h–k, and n–q, 1 nm.

Besides, from the XRD profiles (Supplementary Fig. 3), the diffraction peak at 39.7° corresponding to the (111) plane of Pt crystal was found in Pt/ND@G, which is in good agreement with the STEM observation. There was no prominent diffraction peak observed for Pt0.8Sn/ND@G, which confirms the formation of well-dispersed tiny Pt NPs in Pt0.8Sn/ND@G. In terms of Pt1.7Sn/ND@G, Pt3.4Sn/ND@G, and Pt6.8Sn/ND@G, no diffraction peak of Pt NPs was detected, indicating that Pt clusters were atomically dispersed on the surface of ND@G, consistent well with HAADF-STEM results. To further reveal the unique structure of the catalysts, the Pt dispersion state was determined by H2/O2 titration measurements. For the Pt1.7Sn/ND@G catalyst, the dispersion of Pt was as high as 99.1%, indicating that almost all the Pt atoms were fully exposed on Pt1.7Sn/ND@G. It means that all the Pt atoms on Pt1.7Sn/ND@G are available for adsorptions under the reaction conditions. Meanwhile, excess Sn species partly covered the Pt atoms on Pt3.4Sn/ND@G (the dispersion of Pt was 81.9%) and Pt6.8Sn/ND@G (the dispersion of Pt was 5.6%). In other words, the excess Sn species did not further promote the Pt dispersion but covered up the Pt clusters, preventing Pt atoms from being exposed to adsorbed reactant molecules.

The X-ray adsorption fine structure (XAFS) measurement was employed to provide detailed information of the structure and the local environment of Pt and Sn species. From the X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectroscopy, the intensity of the white line for as-prepared catalysts situated above that of Pt foil, indicating the existence of slightly positively charged Ptδ+ species formed by stabilized on the defect-rich ND@G support (Fig. 2a). The EXAFS spectra of the as-prepared samples (Pt/ND@G, Pt0.8Sn/ND@G, Pt1.7Sn/ND@G, Pt3.4Sn/ND@G, and Pt6.8Sn/ND@G), Pt foil, and PtO2 are shown in Fig. 2b. The detailed EXAFS fitting parameters for these catalysts are shown in Table 1. For the Pt0.8Sn/ND@G catalyst, it exhibited a distinct peak at 1.7 Å and a weak peak at 2.6 Å, which matched up with the first coordination shell of Pt−C/O and Pt–Pt, respectively, indicating that Pt NPs were located on ND@G support through Pt–C bonds. The average CN of Pt−C/O was 3.1, and the average CN of Pt−Pt was 3.2. Notably, for the Pt1.7Sn/ND@G, Pt3.4Sn/ND@G and Pt6.8Sn/ND@G samples, they all showed a strong signal of Pt−C/O and a relatively weak signal of Pt–Pt. For the Pt1.7Sn/ND@G catalyst, the average CN of Pt−Pt is ~2 (2.3), verifying the presence of Pt3 clusters. Due to the limitation of the characterization methods (especially X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS)), the coordination property of Pt atoms is statistically averaged. The realistic Pt clusters on current catalyst could have distribution in both atomicity and configuration42, but the majority of Pt clusters compose of around three Pt atoms. Moreover, all the Pt atoms in the Pt3 clusters (dispersion of Pt was 99.1%) are fully exposed. Significantly, both the features of high dispersion and fully exposure allow all the Pt atoms accessible for adsorbing reactant molecules. For the Pt3.4Sn/ND@G and Pt6.8Sn/ND@G catalyst, the CN of Pt–Pt is 2.0 and 2.1, respectively, similar to that of Pt1.7Sn/ND@G, suggesting that Pt atoms in Pt3.4Sn/ND@G and Pt6.8Sn/ND@G mostly existed in the form of Pt3 clusters. In contrast, for the Pt/ND@G catalyst, the average CN of Pt−Pt bond was 6, indicating the formation of large Pt NPs, agreeing well with the STEM results. The wavelet transformation (WT) of Pt L3-edge EXAFS oscillations visually displayed the structure of Pt species in both the k and R spaces (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 5). Figure 2c is the WT contour plot of Pt1.7Sn/ND@G, showing a Pt–C/O back-scattering contribution near 1.6 Å. Moreover, another minor peak at 2.6 Å in Pt1.7Sn/ND@G can be attributed to the Pt–Pt scattering, further verifying the presence of Pt clusters with low CN. The Fourier transform of k3-weighted EXAFS at Sn K-edge was performed to examine the coordination environment of Sn atoms. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 6, all the samples show an apparent peak at 1.5 Å that corresponds to the first coordination shell of Sn–C or Sn–O, and no Sn–O–Sn or Sn–Sn scattering was observed, indicating the formation of atomically dispersed Sn species. No Pt–Sn bonding was observed, suggesting that Pt and Sn are not in the form of Pt–Sn alloy. The WT of Sn K-edge EXAFS oscillations displayed only a strong signal at 1.5 Å that corresponds to the Sn–C/O coordination (Supplementary Fig. 9), verifying that Sn was atomically dispersed in all the samples. To further confirm the local coordination environment of Pt clusters, the optimized structure of Pt3 cluster by density functional theory calculations is shown in Fig. 2d. A triangular Pt3 cluster is anchored on the ND@G via Pt–C bonds. The mean bond length of Pt–C and Pt–Pt bonds is 2.05 Å and 2.56 Å, respectively, which is in good agreement with the EXAFS measurements in experiment. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 10, the simulated STEM image also shows the monolayered Pt3 clusters on defective graphene surface, in agreement well with the experimental STEM observations. Supplementary Fig. 11 illustrates the relationship between Pt–Pt CN (or Pt dispersion) and Sn/Pt atomic ratio. Notably, with the increase of Sn/Pt atomic ratio from 0 to 1.7, the Pt–Pt CN decreases (and the Pt dispersion increases) in general, suggesting that mono-dispersed Sn species play a vital role in promoting the dispersion of Pt species on ND@G support. However, when the Sn/Pt atomic ratio was beyond 1.7, the Pt–Pt CN kept almost unchanged with the increasing atomic ratio of Sn/Pt. The Pt dispersion decreased to 5.6% at Sn/Pt = 6.8, indicating that the excess amount of Sn did not reduce the size of Pt clusters, but surrounded or covered up the Pt clusters, as shown by the STEM results.

The n-butane DDH reaction was evaluated over Pt/ND@G, Pt0.8Sn/ND@G, Pt1.7Sn/ND@G, Pt3.4Sn/ND@G, and Pt6.8Sn/ND@G to understand the role of Sn species on catalytic performance under the atmospheric condition and at 450 °C. The conversion of n-butane and the selectivity to C4 olefin over those catalysts are shown in Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 2. As shown in Fig. 3a, Pt/ND@G was initially active, and then a fast deactivation of selectivity from 11.6 to 8.2% in 10 h was observed. The n-butane conversion rate over the Pt/ND@G catalyst was only 0.373 mol·gPt−1·h−1. The value of Kd (deactivation rate constant, see its expression in the “reaction analysis” section) and the initial selectivity at 10 h were 0.0421 h−1 and 96.0%, respectively. In general, the deactivation of DDH reaction was attributed to the sintering of Pt NPs with large Pt–Pt CN, resulting in structure-sensitive side reactions and coke formation to block Pt active sites on the catalyst surface43. Notably, benefited from the mono-dispersed Sn, the catalytic performance of Pt0.8Sn/ND@G was dramatically enhanced. The butane conversion reached 25.9% and then dropped to 20.8% in 10 h test. The selectivity towards C4 olefin reached 98.9% at the initial stage. The value of Kd was 0.0313 h−1, showing that the lifetime was extended with decreasing CN of Pt–Pt. Significantly, the Pt1.7Sn/ND@G catalyst possessed excellent catalytic activity and remarkably high selectivity for n-butane DDH. Figure 3a shows that the n-butane conversion reached up to 35.4% and still exhibited a high activity level of 30.9% after 10 h reaction. The selectivity towards C4 olefin was as high as 99.0% at the initial stage, and the value for Kd was only 0.0223 h−1. When further adding Sn species, the conversion and n-butane rate dramatically decreased over the Pt3.4Sn/ND@G and Pt6.8Sn/ND@G catalysts as shown in Fig. 3a, b. However, the C4 olefin selectivity over Pt3.4Sn/ND@G and Pt6.8Sn/ND@G were both close to that of Pt1.7Sn/ND@G. For Pt3.4Sn/ND@G and Pt6.8Sn/ND@G, the structure of atomically dispersed Pt3 was almost intact, but the excess Sn species covered up the Pt3 clusters, causing Pt dispersion decrease from 99.1% to 5.6%, as shown in Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 11. Only a fraction of Pt atoms was available for adsorption during the reaction. Therefore, we conclude that the excess amount of Sn promoter for Pt3 clusters can significantly reduce the conversion and n-butane rate. As shown in Fig. 3b, with the decreasing CN of Pt–Pt, the n-butane conversion rate increased firstly for Pt0.8Sn/ND@G and Pt1.7Sn/ND@G. When Sn/Pt = 1.7, the atomically dispersed Pt3 cluster was thought to be the optimum catalyst, as all the Pt atoms are full exposed for n-butane DDH. Moreover, with the increase of reaction time, the butane conversion and the selectivity for Pt1.7Sn/ND@G catalyst remained constant at 24% even after 50-h of reaction (see Fig. 3c). Additionally, HAADF-STEM images of Pt1.7Sn/ND@G after 10-h in n-butane DDH showed that the fully exposed Pt clusters remained atomically dispersed on ND@G, implying their good stability during the DDH reaction (Supplementary Fig. 12).

Size effect of Pt NP and cluster and SA in butane DDH

To gain insights into the catalyst structure dependence for n-butane DDH reaction, the structure–performance relationship in catalysis was further established by comparing three representative catalysts: Pt/ND@G (Pt NP), Pt1.7Sn/ND@G (Pt3 cluster), and Pt1/ND@G (Pt SA). Firstly, aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM was employed to investigate the morphology of Pt1/ND@G. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 13a and b, individual Pt atoms without any visible clusters or NPs are exhibited as bright dots in high contrast to the ND@G support. The XRD patterns of Pt1/ND@G showed that no Pt crystal or Pt-oxide phase was observed (Supplementary Fig. 13c). In the Pt L3-edge EXAFS spectra (Supplementary Fig. 13d), the sample showed a dominant peak at 1.7–1.8 Å, which can be ascribed to the coordination of Pt atom to light elements such as C or O. Clearly, no Pt–Pt bond was observed, indicating that all the Pt atoms were atomically dispersed on ND@G support, consistent with the HAADF-STEM observation. WT of Pt L3-edge EXAFS (Supplementary Fig. 13e) further revealed the atomic dispersion nature of Pt1/ND@G。

Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 3 summarize the reaction data of Pt/ND@G (Pt NP), Pt1.7Sn/ND@G (Pt3 Cluster), and Pt1/ND@G (Pt SA), respectively. The fully exposed Pt3 clusters showed the best catalytic performance for n-butane DDH reaction than Pt/ND@G and Pt1/ND@G. Clearly, the n-butane DDH rate of Pt1.7Sn/ND@G (1.138 mol·gPt−1·h−1) was higher than those of Pt/ND@G (0.373 mol·gPt−1·h−1) and Pt1/ND@G (0.193 mol·gPt−1·h−1). Consistently, the initial selectivity towards butene on Pt1/ND@G was only 97.1%, followed by Pt1.7Sn/ND@G (96.6%) and Pt/ND@G (93.1%). Figure 4b illustrated the correlation between catalytic activity and coordination number. Generally, dehydrogenation catalysts with small CN have shown high efficiency resulting from their high utilization of metal atoms31. But interestingly, the n-butane conversion rate did not increase proportionally with a decrease of the Pt–Pt CN in Fig. 4b. A maximum butane conversion rate occurred for Pt1.7Sn/ND@G, but Pt1/ND@G.

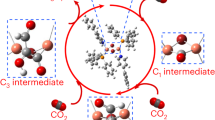

a n-butane conversion and butene selectivity by time-on-stream during n-butane DDH at 450 °C, GHSV = 18000 mL ⋅ gcat−1 ⋅ h−1, n-C4H10:H2 = 1:1 with He balance. b the conversion rate of n-butane in the n-butane DDH and Pt–Pt CN. c energy profile of butane dehydrogenation to 2-butene on the Pt1-Gr, Pt3-Gr, and Pt (111). (purple: Pt1-Gr, red: Pt3-Gr, green: Pt (111)).

To better understand the relationship between metal size and its catalytic performance, DFT calculations were conducted to unveil the difference in dehydrogenation among Pt/ND@G, Pt1.7Sn/ND@G, and Pt1/ND@G. In the DFT calculations, Pt (111) surface, Pt SA on single-lay graphene (Pt1-Gr), and a triangle Pt3 cluster doped into single-vacancy graphene (Pt3-Gr) were used to model Pt/ND@G, Pt1/ND@G, and Pt1.7Sn/ND@G, respectively. The dehydrogenation process follows four steps: (i) the adsorption of n-butane; (ii) the dehydrogenation of n-butane to surface adsorbed 2-C4H9 species (2-C4H9*); (iii) the surface adsorbed 2-C4H8 (2-C4H8*) is generated via the further dehydrogenation of 2-C4H9*; (iv) the desorption of 2-C4H8* to form the product 2-butene gas. Supplementary Tables 4–6 summarize the reaction energy and barriers of butane dehydrogenation for Pt1-Gr, Pt3-Gr, and Pt (111). The Gibbs free energy profile of butane dehydrogenation to 2-butene on these three models is shown in Fig. 4c. One can see that the overall barrier of butane dehydrogenation are 2.52 eV (Pt1-Gr), 1.19 eV (Pt3-Gr), and 2.00 eV (Pt (111)), respectively, suggesting that the Pt3-Gr is the most active for butane dehydrogenation. These data provide a rational interpretation for the high catalytic activity of Pt3-Gr and low activity of Pt1-Gr in our experimental observations. Deep hydrogenation (e.g., further dehydrogenation of 2-butene here) is known to be the origin of coke and hydrogenolysis44. The difference between the energy barriers of deep dehydrogenation (EDH) and the desorption (EDP) of 2-butene (ΔES = EDH − EDP) can be used to evaluate the selectivity of dehydrogenation from alkanes to alkenes44. The more positive of the value ΔES indicates the better selectivity of the catalyst. Supplementary Fig. 20 provides the ΔES for Pt1-Gr (0.45 eV), Pt3-Gr (0.11 eV), Pt (111) (−0.04 eV), respectively. Due to insufficient metal active sites to the further dehydrogenation and weak adsorption of 2-butene, Pt1-Gr exhibits the best selectivity compared to Pt3-Gr and Pt (111). Based on the calculated results, Pt3-Gr is predicted to have high activity and selectivity for the butane dehydrogenation to butene, while Pt1-Gr is expected to have high selectivity and relatively low activity, which agrees well with the aforementioned experimental observations.

Discussion

By optimizing the loading amount of Sn promoter, we fabricated fully exposed Pt3 clusters where the atomically dispersed Sn atoms play the role of geometric partitioning. We constructed the structure–performance relationship between Pt NP, fully exposed Pt3 cluster, and Pt SA for n-butane DDH reaction. The fully exposed Pt3 clusters showed the highest n-butane conversion and remarkable alkene selectivity, compared to Pt NPs and Pt SAs, resulting from the facilitated activation of C–H bond and the desorption of butene. Such relationship between Pt CN and n-butane DDH activity provides a valuable insight in the structure effect on catalytic performance and thus a new avenue to design DDH catalysts with high activity, selectivity, and stability.

Methods

Materials

Nanodiamond (ND) powders with the average diameter of 30 nm were purchased from Beijing Grish Hitech Co., China. Analytical grade chloroplatinic acid (H2PtCl6 ∙ 6H2O) and Tin (II) chloride dehydrate (SnCl2 ∙ 2H2O) as metal precursors were purchased from Sinopharm Co. Ltd.

Catalyst preparation

The nanodiamond@graphene (ND@G) hybrid carbon support was prepared by annealing fresh nanodiamond powders at 1100 °C (heating rate 5 °C·min−1) for 4 h under flowing Ar gas (80 mL·min−1). When it finished and cooled to room temperature, the final powder, ND@G, was collected for further use. A series of PtSn/ND@G catalysts were prepared by co-impregnation method using a fixed weight loading of Pt (0.5%) with varying weight loading of Sn: Pt0.8Sn/ND@G (Sn/Pt atomic ratio = 0.85), Pt1.7Sn/ND@G (Sn/Pt atomic ratio = 1.7), Pt3.4Sn/ND@G (Sn/Pt atomic ratio = 3.4), Pt6.8Sn/ND@G (Sn/Pt atomic ratio = 6.8). First, certain amount of H2PtCl6 (20 g/L) and SnCl2 ∙ 2H2O (6.0 g/L) were dissolved in 1 ml ethanol and generated a clear solution. Then, 100 mg ND@G powder was added and impregnated in the liquid solution. After that, the samples were dried in air at 80 °C for another 6 h. Finally, the solid sample were calcined in Ar (80 mL ⋅ min−1) at 500 °C for 4 h and subsequently reduced in H2 gas (80 mL ⋅ min−1) at 500 °C for 1 h. For reference, the Pt/ND@G (0.5 wt% Pt) was prepared with the same process without the addition of Sn. Pt1/ND@G (0.1 wt% Pt) was also prepared with the similar process without the addition of Sn and reduced by thermal treatment in H2 gas at 200 °C for 1 h.

Characterizations

The series of samples were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) on a D/MAX-2500 PC X-ray diffractometer with monochromated Cu K radiation (λ = 1.54 Å). HAADF-STEM measurements were conducted with a JEOL JEM ARM 200CF aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope at 200 kV accelerating voltage. XAFS measurements of the samples were carried out in Shanghai Synchroton Radiation Facility (SSRF). The H2-O2 titration measurements were performed on a Micromeritics AutoChem II 2920 equipped with a thermal conductive detector.

Reaction analysis

The catalytic test for the DDH reaction of n-butane was tested using a fixed-bed stainless-steel micro-reactor with a quartz lining under atmosphere pressure at 450 °C, equipped with an online gas chromatography instrument (Agilent 7890 with an FID and a TCD detector). First, 50 mg of sample was loaded into the stainless-steel reactor. The reaction was carried out in a feed gas with a composition of 2% H2, 2% n-C4H10 and He as carrier gas, and a gas hour space velocity (GHSV) of 18,000 mL∙gcat−1 ∙ h−1 on the basis of the whole feed gas (the total flow rate is 15 mL∙min–1).

The rate and conversion of n-butane and the selectivity of total C4 olefin (n-butene and 1, 3-butadiene) were calculated by the following formula:

The catalyst stability was described by a first-order deactivation model:

where Ci is initial conversion after reaction 30 min; Cf is final conversion value; t represents the reaction time (h); and kd is the deactivation rate constant (h−1) that is used to evaluate the catalyst stability (the higher kd value is, the lower the stability).

Computational details

The Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) code45,46 was used to perform spin-polarized DFT computations with the projector augmented wave (PAW) method47,48. The generalized gradient approximation in the form of the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functional (PBE)49 was chosen for electron exchange and correlation. An energy cutoff of 400 eV was employed for the plane wave expansion. The ground-state structure of bulk and surfaces were obtained by minimizing forces with the conjugate-gradient algorithm until the force on each ion is below 0.02 eV/Å, and the convergence criteria for electronic self-consistent interaction is 10−5.

A model with Pt3 cluster and Pt single atom embedded into a monovacancy at 5 × 5 supercell of graphene was adopted to simulate the active site of butane dehydrogenation (Pt3-Gr) through comparative investigation between potential Pt cluster models and EXAFS data. The vacuum layer was set to 20 Å to avoid interaction from adjacent cells. The Monkhorst–Pack k-point set to 3 × 3 × 1 in the reciprocal lattice, and the electronic occupancies were determined according to the Gaussian smearing method with σ = 0.1 eV. Spin-polarized calculations were performed. For Pt (111) surface, a four-layer slab with a (3 × 3) supercell (Totally 36 atoms) was employed. The successive slabs were separated by a vacuum region as thick as 20 Å to eliminate periodic interactions. The Brillouin zone is sampled with a 3 × 3 × 1 k-points mesh by the Monkhorst–Pack algorithm. The electronic occupancies were determined according to the Methfessel-Paxton scheme with σ = 0.2 eV. The bottom two layers of the slab were kept fixed to their crystal lattice positions. Spin-polarization is not considered in Pt (111) calculation. We have calculated zero-point energies (ZPE) of reaction species and transition states.

The most stable configurations of the reactant and intermediates on Pt3-Gr, Pt1-Gr and Pt (111) surface were obtained by the standard minimization of density functional theory (DFT). These configurations were used as the initial states, from which the constrained optimization method as described by Plessow. P. N50. was used to search the transition states (TS). The TS optimization convergence was regarded to be achieved when the force on each atom was less than 0.05 eV/Å. All transition states have been verified to include only one imaginary harmonic frequency corresponding to the transition vector of the reaction. Furthermore, small distortions along the transition vector followed by optimization toward the minima verified the connectivity of the transition states. The entropy contributions of butane, 2-butene and hydrogen gas were included in the free energy calculations. The most important contributions arise from the translational entropy51, which can be calculated using the following equation:

where M, R, k, h, T, and P refer to the molecular weight, ideal gas constant, Boltzmann constant, Plank constant, temperature and pressure, respectively. In the energy diagrams shown in Fig. 3c, the free energies were reported at under conditions (723.15 K and 100 kPa), it was estimated that n-butane in the gas phase lost 1.34 eV of entropic energy (TS) in the adsorption; the desorption of 2-butene and H2 gas gained 1.34 eV and 1.02 eV. It should be noted that the partial calculation work on the Pt3-Gr model is based on the theoretical part of our previous work35, and has been further improved in the Gibbs free energy calculations according to the main contribution of translational entropy.

Data availability

The data supporting this article and other findings are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Change history

30 June 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24374-4

References

Liu, L. & Corma, A. Metal catalysts for heterogeneous catalysis: from single atoms to nanoclusters and nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 118, 4981–5079 (2018).

Cao, S., Tao, F. F., Tang, Y., Li, Y. & Yu, J. Size- and shape-dependent catalytic performances of oxidation and reduction reactions on nanocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 4747–4765 (2016).

Ren, Y. et al. Unraveling the coordination structure-performance relationship in Pt1/Fe2O3 single-atom catalyst. Nat. Commun. 10, 4500 (2019).

Jin, R. et al. Low temperature oxidation of ethane to oxygenates by oxygen over iridium-cluster catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 18921–18925 (2019).

Lang, R. et al. Non defect-stabilized thermally stable single-atom catalyst. Nat. Commun. 10, 234 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. A stable low-temperature H2-production catalyst by crowding Pt on alpha-MoC. Nature 589, 396–401 (2021).

Yao, S. et al. Atomic-layered Au clusters on alpha-MoC as catalysts for the low-temperature water-gas shift reaction. Science 357, 389–393 (2017).

Lin, L. et al. Low-temperature hydrogen production from water and methanol using Pt/alpha-MoC catalysts. Nature 544, 80–83 (2017).

Li, S. et al. Atomically dispersed Ir/α-MoC catalyst with high metal loading and thermal stability for water-promoted hydrogenation reaction. Natl Sci. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwab026 (2021).

Ge, Y. Z. et al. Maximizing the synergistic effect of CoNi catalyst on alpha-MoC for robust hydrogen production. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 628–633 (2021).

Lin, L. L. et al. Atomically dispersed Ni/alpha-MoC catalyst for hydrogen production from methanol/water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 309–317 (2021).

Huang, F. et al. Anchoring Cu1 species over nanodiamond-graphene for semi-hydrogenation of acetylene. Nat. Commun. 10, 4431 (2019).

Qiao, B. et al. Single-atom catalysis of CO oxidation using Pt1/FeOx. Nat. Chem. 3, 634–641 (2011).

Sun, X. et al. Facile synthesis of precious-metal single-site catalysts using organic solvents. Nat. Chem. 12, 560–567 (2020).

Yang, Z. et al. Coking-resistant iron catalyst in ethane dehydrogenation achieved through siliceous zeolite modulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 16429–16436 (2020).

Lee, S. S., Fan, C. Y., Wu, T. P. & Anderson, S. L. CO oxidation on Aun/TiO2 catalysts produced by size-selected cluster deposition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 5682–5683 (2004).

Liu, L. et al. Determination of the evolution of heterogeneous single metal atoms and nanoclusters under reaction conditions: which are the working catalytic sites? ACS Catal. 9, 10626–10639 (2019).

Fernandez, E. et al. Low-temperature catalytic NO reduction with CO by subnanometric Pt clusters. ACS Catal. 9, 11530–11541 (2019).

Kwak, J. H., Kovarik, L. & Szanyi, J. CO2 reduction on supported Ru/Al2O3 catalysts: cluster size dependence of product selectivity. ACS Catal. 3, 2449–2455 (2013).

Li, S. et al. Tuning the selectivity of catalytic carbon dioxide hydrogenation over iridium/cerium oxide catalysts with a strong metal-support. Interact. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 10761–10765 (2017).

Baxter, E. T., Ha, M.-A., Cass, A. C., Alexandrova, A. N. & Anderson, S. L. Ethylene dehydrogenation on Pt4,7,8 clusters on Al2O3: strong cluster size dependence linked to preferred catalyst morphologies. ACS Catal. 7, 3322–3335 (2017).

Dong, C. et al. Supported metal clusters: fabrication and application in heterogeneous catalysis. ACS Catal. 10, 11011–11045 (2020).

Gates, B. C. Supported metal-clusters-synthesis, structure, and catalysis. Chem. Rev. 95, 511–522 (1995).

Hu, Q. et al. Facile synthesis of sub-nanometric copper clusters by double confinement enables selective reduction of carbon dioxide to methane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 19054–19059 (2020).

Tian, S. et al. Carbon nitride supported Fe2 cluster catalysts with superior performance for alkene epoxidation. Nat. Commun. 9, 2353 (2018).

Yan, H. et al. Bottom-up precise synthesis of stable platinum dimers on graphene. Nat. Commun. 8, 1070 (2017).

Kokalj, A. et al. Methane dehydrogenation on Rh@Cu(111): a first-principles study of a model catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 12448–12454 (2006).

Zhao, Z., Chiu, C. & Gong, J. Molecular understandings on the activation of light hydrocarbons over heterogeneous catalysts. Chem. Sc. 6, 4403–4425 (2015).

Furukawa, S., Tamura, A., Ozawa, K. & Komatsu, T. Catalytic properties of Pt-based intermetallic compounds in dehydrogenation of cyclohexane and n-butane. Appl. Catal. A. Gen. 469, 300–305 (2014).

Ballarini, A. D. et al. n-Butane dehydrogenation on Pt, PtSn and PtGe supported on gamma-Al2O3 deposited on spheres of alpha-Al2O3 by washcoating. Appl. Catal. A. Gen. 381, 83–91 (2010).

Sattler, J. J., Ruiz-Martinez, J., Santillan-Jimenez, E. & Weckhuysen, B. M. Catalytic dehydrogenation of light alkanes on metals and metal oxides. Chem. Rev. 114, 10613–10653 (2014).

Nagaraja, B. M., Shin, C.-H. & Jung, K.-D. Selective and stable bimetallic PtSn/theta-Al2O3 catalyst for dehydrogenation of n-butane to n-butenes. Appl. Catal. A. Gen. 467, 211–223 (2013).

Sun, G. et al. Breaking the scaling relationship via thermally stable Pt/Cu single atom alloys for catalytic dehydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 9, 4454 (2018).

Zhu, Y. et al. Lattice-confined Sn (IV/II) stabilizing raft-Like Pt clusters: high selectivity and durability in propane dehydrogenation. ACS Catal. 7, 6973–6978 (2017).

Zhang, J. Y. et al. Tin-assisted fully exposed platinum clusters stabilized on defect-rich graphene for dehydrogenation reaction. ACS Catal. 9, 5998–6005 (2019).

Xu, Z., Yue, Y., Bao, X., Xie, Z. & Zhu, H. Propane dehydrogenation over Pt clusters localized at the Sn single-site in zeolite framework. ACS Catal. 10, 818–828 (2020).

Liu, L. et al. Regioselective generation and reactivity control of subnanometric platinum clusters in zeolites for high-temperature catalysis. Nat. Mater. 18, 866–873 (2019).

Liu, L. et al. Structural modulation and direct measurement of subnanometric bimetallic PtSn clusters confined in zeolites. Nat. Catal. 3, 628–638 (2020).

Wang, Y., Hu, Z. P., Lv, X., Chen, L. & Yuan, Z. Y. Ultrasmall PtZn bimetallic nanoclusters encapsulated in silicalite-1 zeolite with superior performance for propane dehydrogenation. J. Catal. 385, 61–69 (2020).

Sun, Q. et al. Subnanometer bimetallic platinum-zinc clusters in zeolites for propane dehydrogenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 19450–19459 (2020).

Huang, F. et al. Atomically dispersed Pd on nanodiamond/graphene hybrid for selective hydrogenation of acetylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 13142–13146 (2018).

Peng, M. et al. Fully exposed cluster catalyst (FECC): toward rich surface sites and full atom utilization efficiency. ACS Cent. Sci. 7, 262–273 (2021).

Lian, Z. et al. Revealing the Janus character of the coke precursor in the propane direct dehydrogenation on Pt catalysts from a kMC simulation. ACS Catal. 8, 4694–4704 (2018).

Yang, M., Zhu, Y., Zhou, X., Sui, Z. & Chen, D. First-principles calculations of propane dehydrogenation over PtSn catalysts. ACS Catal. 2, 1247–1258 (2012).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blochl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1396–1396 (1997).

Plessow, P. N. Efficient transition state optimization of periodic structures through automated relaxed potential energy surface scans. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 14, 981–990 (2018).

Campbell, C. T. & Sellers, J. R. V. The entropies of adsorbed molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 18109–18115 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFA0204100, 2017YFB0602200), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91845201, 21961160722, 22072162, 21703261, 21725301, 21932002, and 21821004), the Liaoning Revitalization Talents Program XLYC1907055, and the Sinopec China. N.W. hereby acknowledges the funding support from the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (Project Nos. C6021-14E, N_HKUST624/19 and 16306818). The XAS experiments were conducted in Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF). D.M. thank OSSO State Key Lab for support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L. and D.M. conceived the research. X.Ch. conducted material synthesis and carried out the catalytic performance test. M.P., B.M., Y.D., and Zhe.J. conducted the X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopic measurements and analyzed the data. Y.C. and X.W. performed the DFT calculations. X.Ca. and N.W. contributed to the aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy. Zhi.J. performed some of the experiments. The manuscript was primarily written by X.Ch., D.X., H.L., and D.M. All authors contributed to discussions and manuscript review.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Peng, M., Cai, X. et al. Regulating coordination number in atomically dispersed Pt species on defect-rich graphene for n-butane dehydrogenation reaction. Nat Commun 12, 2664 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22948-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22948-w

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.