Abstract

Monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) have become essential two-dimensional materials for their perspectives in engineering next-generation electronics. For related applications, the controlled growth of large-area uniform monolayer TMDs is crucial, while it remains challenging. Herein, we report the direct synthesis of 6-inch uniform monolayer molybdenum disulfide on the solid soda-lime glass, through a designed face-to-face metal-precursor supply route in a facile chemical vapor deposition process. We find that the highly uniform monolayer film, with the composite domains possessing an edge length larger than 400 µm, can be achieved within a quite short time of 8 min. This highly efficient growth is proven to be facilitated by sodium catalysts that are homogenously distributed in glass, according to our experimental facts and density functional theory calculations. This work provides insights into the batch production of highly uniform TMD films on the functional glass substrate with the advantages of low cost, easily transferrable, and compatible with direct applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) have opened new perspectives for engineering next-generation electronics and optoelectronics, thanks to their unique physical and chemical properties different from their bulk counterparts1,2,3,4,5. In particular, direct band gap semiconductors, such as MoS2 and WS2, exhibit ultrahigh optical responsivity6, efficient valley polarization7,8 and strong light–matter coupling9, making them highly promising materials for constructing electrical/optical and energy-related devices. For such applications, the controllable synthesis of large-area uniform and large-domain monolayer TMDs is highly desired, while still challenging. This challenge is similarly encountered in graphene researches, and many efforts have been made in recent decades10.

To date, various techniques have been developed to synthesize TMDs, including physical vapor deposition11, metal organic chemical vapor deposition12,13, chemical vapor deposition (CVD)14,15, etc. Among these, the CVD has been recognized as the most promising route for directly synthesizing large-area uniform multi- or monolayer TMD materials16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. Specifically, three strategies have been employed to deliver the metal precursors during the CVD process: the “pre-deposited” route, “point-to-face” supply, and “face-to-face” feeding methods. Taking the synthesis of MoS2 as an example, pre-deposition of Mo layers and MoO2 microcrystals followed by sulfurization processes were developed by Zhan et al.17 and Wang et al.18, respectively, for realizing the large-area growth of thin-layer MoS2 films. However, the TMDs usually evolved as polycrystalline layers due to limited migration/diffusion of metal precursors on macroscopic-scale surfaces. Subsequently, a point-to-face metal-precursor supply method was proposed to grow large-domain TMDs with controllable thicknesses. Lee et al. reported the successful synthesis of MoS2 atomic layers on SiO2/Si by mounting the substrate face-down over the MoO3 powder and sulfur precursors20. In addition, the substrate was also spin-coated with graphene-like molecules to promote the layered growth of MoS2. Without using seeds, Najmaei et al. demonstrated the synthesis of triangular domains and continuous MoS2 films by placing MoO3-nanoribbon-covered plate on the silicon substrate to reveal the nucleation and grain boundary formation mechanism26.

Notably, a point-to-face metal-source supply method has shown great potential for obtaining large-domain TMD monolayers using metal oxides (e.g, MoO3, MoO2) precursors placed upstream of (or below) the substrates. However, achieving large-scale uniform monolayer TMDs (over several centimeters) remains challenging, due to the variable release rates of the metal precursor and its inhomogeneous distribution along the gas-flow direction27,28. To guarantee a sufficient and uniform delivery of the metal precursor, a face-to-face deposition method was then proposed. Specifically, Yun et al. reported the direct synthesis of 2 × 3 cm2 uniform monolayer WS2 films by arranging (NH4)6H2W12O40·x(H2O) (AMT)-loaded Al2O3 plate above Au substrates29. However, the feeding rate of the precursors achieved through the two-step solution-processed assembly was still uncontrollable, and the method was too tedious to apply. Chen et al. reported the fast growth of millimeter-size monolayer MoSe2 crystals on molten glass22. A piece of Mo foil placed on SiO2/Si was used to hold the glass substrate. Very recently, the same group achieved the homoepitaxial growth of MoS2 patterns on monolayer MoS2 at a growth temperature of 1050 °C23. In the growth process, a piece of curved Mo foil was placed above the molten glass substrate serving as the Mo source. The ionic compounds in glass corroded the Mo foil thus helping with the volatilization of Mo, and resulting in a face-to-face metal-precursor feeding pathway.

Herein, we design a facile face-to-face metal-precursor supply strategy in the conventional CVD growth process, for synthesizing large-scale uniform, monolayer MoS2 by selecting a novel solid glass substrate and using Mo foil and sulfur as precursors. Soda-lime glass is chosen as the substrate as it is cost-effective and scalable, thus suitable for the batch production of monolayer MoS2 films. Meanwhile, the coating of MoS2 on glass endows it with novel optical and catalytic properties. Particularly, the large-scale uniformity, crystallinity, and growth efficiency of MoS2 on soda-lime glass substrate are carefully evaluated via detailed characterizations from atomic to centimeter scales. The ultrafast growth of MoS2 with the aid of trace amount of Na catalysts from the glass substrate is also discussed, according to intensive experimental efforts and density functional theory (DFT) calculations. In addition, by exploiting the hydrophilicity of the glass substrate, we also develop an etching-free transfer process for transferring inch-scale MoS2 films onto target substrates. This work, hereby, provides novel insights into the batch production and transfer of macroscopic uniform TMD films, which will propel their practical applications in various fields.

Results

Face-to-face metal-precursor feeding route

In order to obtain a highly uniform monolayer MoS2 film, we designed a unique face-to-face metal-precursor feeding route. As schematically illustrated in Fig. 1a, a Mo foil was placed above the soda-lime glass substrate in a parallel geometry with a gap of 10 mm. This configuration ensures a homogeneous supply of the Mo precursor through an onsite heating process with the aid of an O2 carrier (Supplementary Fig. 1). The concentration of the S precursor is usually oversaturated during the CVD growth process30. For the batch production purpose, commercial soda-lime glass (mainly composed of SiO2, Na2O, and CaO) was selected as the growth substrate considering the following factors: first, its low cost and scalability guarantees the cost-effective production of MoS2/glass hybrid materials; second, its hydrophilicity feature facilitates the transfer of MoS2 films to other substrates; third, the MoS2/glass hybrid itself may serve as a prototype material for directly fabricating optical and photoelectric devices due to its relatively high transparency (exceeds 91% at a wavelength λ = 550 mm). It is worthy of mention that the molten glass has been utilized as an ideal substrate for graphene growth in our previous efforts31. In another work, Ju et al. proposed the self-limited monolayer growth mechanism of MoS2 on molten glass for it is capable of trapping overflowing MoO3 precursors32. In contrast, the growth temperature in our system is set to 720 °C in order to preserve the original surface morphology of the glass substrate, thus providing higher potential for the batch production and the direct application of the hybrid material.

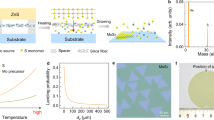

LPCVD growth of large-area uniform, monolayer MoS2 on soda-lime glass. a Schematic diagram of a face-to-face metal-precursor supply route. b Photograph of a 6-inch continuous MoS2 film on soda-lime glass synthesized for ~8 min. c Typical OM image of the MoS2 film, scale bar: 0.2 mm. d Raman (left panel) and PL (right panel) spectra of the as-grown MoS2, confirming its monolayer feature. e Raman mapping on the intensity of A1g peak for the continuous MoS2 film, scale bar: 10 µm. f OM image of triangular MoS2 domains on glass grown for ~5 min with the other parameters kept identical. Scale bar: 0.1 mm. g AFM image of the edge of a MoS2 crystal (transferred onto SiO2/Si) and its corresponding height profile. Scale bar: 1 µm. h Comparison of the uniform area (bars) and growth time (green squares) of monolayer MoS2 on glass and other monolayer TMDs on various substrates reported in the literatures14,26,29,38,39,40,41,42,43,44

In the low-pressure (LP) CVD process, an adequate sulfur vapor was conveyed downstream by a flow of Ar (50 sccm) and O2 (6 sccm). The O2 carrier was introduced to oxidize the Mo foil for directly releasing chemically active MoO3−x (x = 2, 3). This intermediate precursor presents relatively low sublimation temperature of about 500 °C, right below the melting point of the soda-lime glass. Notably, this temperature is much lower than that needed for the direct release of Mo atoms from Mo foils (~2600 °C). Generally, MoO3−x is regarded as active species for the CVD synthesis of MoS219,33. As shown in Fig. 1b, at relatively short growth time of 8 min, a 14 × 6 cm2 uniform, full-covered MoS2 film is synthesized on the glass substrate at 720 °C by a LPCVD strategy (see the Methods section). After this growth process, deformation of the glass substrate is negligible; however, its surface color changes from transparent to light brown, indicating the formation of MoS2.

According to the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) data, the Mo 3d5/2 (at 229.4 eV) and 3d3/2 (at 232.6 eV) peaks are in line with Mo4+ (Supplementary Fig. 2), and S 2p3/2 (at 162.2 eV) and 2p1/2 (at 163.4 eV) peaks are assigned to S2−. These results agree well with the standard XPS data for MoS218, thus suggesting the formation of a MoS2 film. Moreover, the typical optical microscopy (OM) of the sample surface shows a highly uniform color contrast, indicating the homogenous thickness and in-plane continuity of the MoS2 film (Fig. 1c).

The layer thickness and crystal quality of the achieved MoS2 film were then determined by Raman spectroscopy and photoluminescence (PL) analyses. As shown in Fig. 1d, the randomly selected Raman spectra (collected from the 100 sampling points on the MoS2-covered glass) exhibit two characteristic peaks of MoS2, corresponding to the E12g (at 385.7 cm−1) and A1g (at 406.2 cm−1) vibration modes, respectively. The specific frequency difference (∆) is 20.5 cm−1, highly indicative of the monolayer nature of the obtained film34. Moreover, the typical PL spectrum presents a sharp excitonic A peak at 1.88 eV (660 nm), its relatively high intensity and narrow full-width at half-maximum (54 meV) confirm the rather high crystallinity of our CVD-derived monolayer MoS235. Moreover, Raman mapping on the intensity of A1g mode manifests an extra uniform color contrast, further demonstrating its perfect thickness uniformity and good crystallinity over a large scale (Fig. 1e).

In order to investigate the intrinsic crystal quality, the growth time was deliberately reduced to 5 min. Large triangular domains are observed to be evenly dispersed on the surface by OM images, presenting an average edge length of ~200 µm (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 3). In this regard, the continuous film is proposed to arise from the merging of composite domains, either by extending the growth time or by increasing the precursors feeding rate. Notably, in a continuous monolayer film, the average domain size obtained in this work is much larger than previously reported ones synthesized on SiO2/Si26,28 or on Au foils36.

Interestingly, the domain size of the triangular MoS2 crystals is tunable by controlling the gap distance between the Mo foil precursor and the glass substrate. When the gap is decreased from 50 to 10 mm, the nucleation density reduces dramatically, and the average edge length of the resulting domains increases from 1 to 400 µm. This phenomenon is attributed to the gradual reduction in sulfur concentration over the gap region, which suppresses the nucleation density and increases the domain size accordingly. However, when the gap is further reduced to 2 mm, irregularly shaped MoO x S2−x crystals appear on the sample surface due to an insufficient feeding of the S precursor, similar to the observation from the published reference37 (Supplementary Fig. 4). In addition, the MoS2 domains also increase in size with increasing concentration of O2 (from 1 to 6 sccm), due to the gradually increased oxidization of the Mo foil and sufficient supply of the metal precursor (Supplementary Fig. 5).

In order to accurately determine the thickness of the MoS2 film, a modified polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA)-assisted method was also developed to transfer the as-grown MoS2 film onto the SiO2/Si substrate, which will be discussed later. Figure 1g shows an atomic force microscopy (AFM) image of a MoS2 domain edge, and the corresponding height profile reveals a value of 0.77 nm, the same as that of the previously reported data for a monolayer thickness20. Notably, using the current face-to-face metal-precursor feeding route, the thickness uniform region is much larger than that of previously reported ones using the pre-deposited and point-to-face metal-precursor supply methods (Fig. 1e)14,26,29,38,39,40,41,42,43,44. For the batch production capability, the maximum sample size is only limited by the diameter of the tube furnace (3-inch diameter for the current experiment); larger sample size is attainable by increasing the size of the furnace.

To highlight the excellent thickness uniformity of the 6-inch monolayer MoS2 film on glass synthesized through a face-to-face metal-precursor feeding method, a point-to-face feeding route with the MoO3 powder precursor was also utilized to grow MoS2 on glass for comparison. Digital photographs of two pieces of 6-inch MoS2/glass samples, synthesized with the MoO3 powder placed upstream and the Mo foil placed on top, are displayed in Fig. 2a and c, respectively. Notably, the different thickness uniformity of the two-type samples is visible even to the naked eye. A “point-to-face” route-derived MoS2/glass shows gradually fading brown color along the gas-flow direction (d = 1–8 cm, where d denotes the distance from the left edge of the sample shown in the photograph), and the glass surface is almost colorless at the downstream location d = 8–14 cm. More specifically, the corresponding OM images of the selected points A1, B1, and C1 (marked in Fig. 2a with circles, corresponding to d = 1, 4, and 7 cm, respectively), present the characteristic morphologies of multilayer domains, larger monolayer domains (edge length 300 µm), and smaller monolayer domains (edge length 40 µm), respectively.

Comparison of MoS2 synthesized by a point-to-face and face-to-face metal-precursor supply routes. a, c Photographs of MoS2 growth on 6-inch soda-lime glass using a MoO3 powder and c Mo foil as precursors. The gas-flow direction was from left to right in both cases. b, d Corresponding OM images of MoS2 synthesized using b MoO3 powder and d Mo foil as precursors, at the points labeled A1, B1, and C1 in a and A2, C2, and E2 in c (with the different locations marked by colored letters; scale bars: 100 µm). e, f Corresponding Raman spectra of MoS2 synthesized with the MoO3 powder and the Mo foil precursors, respectively, at the points labeled A–E in a and c. g, h Color-coded images of the typical Raman modes for the samples shown in a and c, respectively, collected from 70 positions (with an interval of 2 mm along the horizontal direction)

On the other hand, nearly homogenous contrast (uniform light-brown color) is noticeable over the entire face-to-face route-derived sample (Fig. 2c). Corresponding OM images of the points marked with A2, C2, and (shown by triangles in Fig. 2c) for d = 1, 4, and 13 cm, respectively, reveal a highly uniform color contrast over the entire surface, reconfirming the centimeter-scale uniformity of the obtained monolayer MoS2 films. To address the remarkably different thickness uniformity of the two-type samples, Raman spectra were also recorded at the five points (A to E) indicated in Fig. 2a, c. For a point-to-face precursor-feeding method, ∆ of the two characteristic peaks (E12g and A1g) decreases from ~22.6 to ~20.7 cm−1 along the upstream points (positions A1 and B1 in Fig. 2a), consistent with the thickness change from multilayer to monolayer (also shown in the OM images). In addition, only a faint Raman signal is visible at the downstream points (positions C1, D1, and E1 in Fig. 2a) due to the few nucleation sites.

However, the Raman spectra for a face-to-face precursor-feeding derived sample are nearly identical for various locations along the sample, with the characteristic ∆ value of 20.5 cm−1, highly indicative of its superior thickness uniformity (Fig. 2f). Moreover, Raman data from 70 typical locations (with an interval of 2 mm) were also collected in Fig. 2g and h for the two-type samples. Clearly, a “face-to-face” precursor-feeding derived sample exhibits excellent thickness uniformity in peak intensity and frequency difference (∆ of 20.6 ± 0.3 cm−1).

The disparate film thickness uniformities of the two-type MoS2/glass samples (synthesized using a face-to-face and point-to-face metal-precursor feeding routes) can be explained by the different concentration gradients of the Mo species over the substrate surfaces. In the latter case, the MoO3 powder is partially reduced by the sulfur vapor to form volatile MoO3−x species, which are subsequently transported downstream by the gas flow and react with sulfur19. Apparently, the concentration of the MoO3−x species gradually decreases along the gas-flow direction, leading to smaller and sparser MoS2 crystals at the downstream positions. However, in our designed growth strategy, wherein the Mo foil is placed face-to-face to the glass substrate, the MoO3–x species arising from the oxidized Mo foil can be uniformly released into the gap between Mo foil and glass, resulting in homogenous nucleation and growth over the entire glass surface. Accordingly, a large-area uniform monolayer MoS2 film is unexceptionally obtained.

Growth mechanism of monolayer MoS2 on soda-lime glass

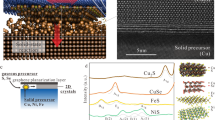

In our experiments, the continuous 6-inch monolayer MoS2 film is usually synthesized on glass at a quite short time of 8 min, in line with an edge growth rate of around 1.2 µm s−1. Notably, this growth rate is much faster than that on common insulating substrates, such as SiO2/Si (15 min; 0.4 µm s−1)26 and sapphire (30 min; 0.2 µm s−1)24. The glass substrate, thereby, plays a crucial role in the fast growth of monolayer MoS2 films. To understand this, the MoS2 growth both on soda-lime glass (mainly composed of SiO2, Na2O, and CaO) and quartz (mainly composed of SiO2) were compared in detail. Typical OM images of MoS2 grown for different time durations on soda-lime glass (2–8 min) and on quartz (10–70 min) are presented in Fig. 3a and b, respectively. This growth time difference should justify their different growth rates in general. As for the surface morphology, well-defined triangular flakes with an edge length of hundreds of microns can be noticed on glass, and the coverage is precisely tunable from 43 to 100% with increasing growth time from 2 to 8 min (with an interval of 2 min) (Fig. 3a, from left to right). In contrast, when using the same growth parameter, there is much poorer control of the morphology of MoS2 on quartz with the growth time varying from 10 to 70 min (with an interval of 20 min) (Fig. 3b, from left to right). The sample is characterized with much smaller domain sizes (edge lengths 5–10 μm), high density of nucleation sites, and nonuniform thicknesses. Moreover, according to statistical results, the coverage of MoS2/glass increases monotonically with growth time, and the growth rate is approximately 38 times higher than that on quartz (Fig. 3c; as calculated from the coverage expansion per minute). Intriguingly, by placing a piece of soda-lime glass on the upstream area of the quartz substrate, the domain size and the growth rate of MoS2 on quartz are significantly increased (Supplementary Fig. 6). Considering the different chemical compositions of soda-lime glass and quartz, the metallic elements in glass, e.g., Na and Ca, should take effect in the fast growth of MoS2.

The role of Na from soda-lime glass in promoting the growth rate of monolayer MoS2. Growth-time-dependent OM images of MoS2 synthesized on a soda-lime glass with growth time from 2 to 8 min (scale bars: 100 µm) and b quartz glass from 10 to 70 min (scale bars: 50 µm). Other than the substrate type, all experimental parameters were identical for the samples shown in a and b. c MoS2 coverage as a function of growth time on soda-lime glass (red) and quartz (blue). d MoS2 coverage as a function of growth time on quartz substrates either placed downstream from the glass (green) or spin-coated with NaCl (pink) prior to growth. e, f DFT-calculated energy diagrams for MoS2 growth along the S-terminated edges, e without and f with Na adsorption. The blue, yellow, and purple spheres represent molybdenum, sulfur, and sodium atoms, respectively

To confirm this, a quartz substrate was spin-coated with a solution of CaCl2 (0.01 g ml−1) or NaCl (0.01 g ml−1) before depositing MoS2. The derived MoS2 layer on the CaCl2-coated quartz exhibits nonuniform thicknesses and irregular domain shapes (Supplementary Fig. 7), indicating that the effect of Ca is negligible for accelerating the growth of MoS2. However, for the quartz substrate coated with NaCl, both the domain size and surface coverage of MoS2 are significantly enhanced (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 6). Statistically, the average growth rate of MoS2 on quartz with the assistance of upstream glass or spin-coated with NaCl is approximately 13 times faster than that on pure quartz (Fig. 3d).

In order to exclude the contribution of Cl, quartz spin-coated with NaOH solution (0.01 g ml−1) was also employed as a substrate for MoS2 growth. The result is quite similar to that for NaCl-coated substrate (Supplementary Fig. 8). Based on these experiments, the Na element in the soda-lime glass is considered to serve as a very effective promotor in the fast growth of MoS2. As an additional proof, Na is also detected in the oxidized Mo foil after MoS2 growth, as evidenced by XPS spectra (Supplementary Fig. 9). Thus, Na is expected to be widely distributed in the confined space between Mo foil and glass during the CVD growth process. However, after being transferred onto SiO2/Si, no Na signal appears for the monolayer MoS2 film, confirming that Na only serves as an intermediate catalyst for the rapid growth of MoS2 (Supplementary Fig. 9).

DFT calculations were then performed to provide an in-depth understanding of the growth mechanism. The energy diagrams for MoS2 growth along the S-terminated edges were calculated with and without Na adsorption (for the first six reaction steps), as displayed in Fig. 3e and f, respectively. With the incorporation of Na, the highest energy barrier (that of the step from Mo2S2 to Mo2S4) reduces from 0.53 to 0.29 eV for MoS2 growth. Assuming that the rates of atom attachment (S2 and Mo) are the same for the two cases, the ratio of growth rate with Na to that without Na is estimated as exp[(0.53–0.29)k−1T−1] ≈ 17 at T = 1000 K. This result is in good agreement with the experimental data shown in Fig. 3c. Meanwhile, for the growth of MoS2 along the Mo-terminated edge (Supplementary Fig. 10), the energy barriers are calculated to be 1.29 and 2.04 eV for those with and without Na assistance, respectively. Much faster growth of the S-terminated edge indicates the preferential evolution of Mo-terminated edges according to the published reference27, which corroborates our experimental results (as will be discussed in Fig. 4e).

Atomic structure of transferred monolayer MoS2. a OM image of a transferred MoS2 domain on a carbon TEM grid, scale bars: 100 µm. b–d SAED patterns from the regions numbered 1–3 in a. The dashed lines indicate the rotation angles (75.01°, 75.15°, and 75.43°) with respect to the horizontal line (scale bar: 3 nm−1). e STEM (upper) image of the MoS2 domain edge and the enlarged view (lower) of the marked rectangular region. Scale bars: 20 and 1 nm, respectively. f Atomically resolved image representing the defect-free hexagonal structure of MoS2. The bright spots are Mo atoms and the gray spots correspond to two-stacked S atoms. Scale bars: 1 nm. g Representative Moiré-scale STM image of MoS2 transferred on HOPG (VT = −0.21 V, IT = 5.19 nA, scale bar: 5 nm) and h corresponding atomic-resolution STM image (VT = −0.33 V, IT = 5.19 nA, scale bar: 2 nm). The arrows indicate the directions of the MoS2 lattice (yellow) and the Moiré pattern (blue). The unit cell for the Moiré pattern is outlined with a rhombus (period of 1.06 ± 0.05 nm)

Atomic structure characterizations of the crystal quality

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM), scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM), and scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) were then utilized to evaluate the crystal quality of the CVD-derived monolayer MoS2. Figure 4a shows an OM image of a typical triangular MoS2 domain with an edge length of 409 µm. Selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns regarding the numbered regions (1, 2, and 3 in Fig. 4a) present nearly identical lattice orientations (deviation smaller than ± 0.5°), suggesting the single-crystal nature of the MoS2 triangular domain (Fig. 4b–d). Moreover, the atomically resolved image from the domain edge presents a Mo-terminated zigzag edge type (Fig. 4e), which agrees well with the previously published result28. Specifically, the lattice inside the domain presents a well-organized honeycomb lattice with an interatomic distance of approximately 0.32 nm (Fig. 4f), which is identical to that previously documented for MoS245. And the nearly defect-free structure confirms the rather high crystal quality of the CVD-derived MoS2 on glass.

In order to present the relatively high stability and perfect crystal quality, the monolayer MoS2 flake was transferred onto a highly oriented pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) substrate for STM characterizations. Large-area uniform, hexagonal Moiré patterns are universally observed to show a period of 1.06 ± 0.05 nm (Fig. 4g, as marked by a rhombus in Fig. 4h), which arises from the lattice mismatch between MoS2 (a1 = 0.312 nm) and graphite (a2 = 0.246 nm). Briefly, STEM and STM observations provide consistent proof of the relatively high crystal quality of CVD-derived monolayer MoS2, as well as its perfect stability during the harsh sample transfer process.

Green transfer and electronic property characterizations

To fulfill the applications of large-area uniform monolayer MoS2, a convenient transfer process is highly desirable. To date, two-predominant strategies using PMMA as the supporting layer have been demonstrated, i.e., electrochemical bubbling and wet chemical etching methods. The former is mainly used to transfer monolayer TMDs on conductive substrates, such as Au foils, by virtue of the weak interfacial interaction14,29. In the latter case, structural damage and performance degradation usually occur due to the use of acidic and alkaline solutions44. To mitigate this issue, facile/rapid, environmentally friendly transfer routes need to be developed for specific growth systems. Recently, Gurarslan et al.46 and Xu et al.47 have developed similar methods to transfer MoS2 and WS2 from sapphire, based on the hydrophilic behavior of the sapphire substrate and the accompanying capillary force. For the former work, the polymer/MoS2 stack needed to be picked up from the water droplet and then transferred onto target substrates, which can hardly ensure the large-scale continuity of the large-size samples. For the latter work, a NaOH solution pre-etching process was highly necessary to open a gap between polymer and sapphire, which inevitably caused damage to both sample and substrate.

In this work, by virtue of the hydrophilicity of the glass substrate, an etching-free, easy processing, and scalable transfer strategy was developed for the high-quality transfer of large-area uniform samples (Supplementary Fig. 11). As illustrated in Figs. 5a and d, both PMMA-assisted and the roll-to-roll transfer strategies were designed to transfer MoS2 from glass to SiO2/Si and ethylene vinyl acetate/polyethylene terephthalate (EVA/PET) substrates, respectively. For the transfer to rigid substrates, a modified PMMA-assisted transfer process involving three essential steps was developed: first, spin-coating PMMA on MoS2/glass; then making cracks along the edge of PMMA/MoS2 with a knife, inducing natural penetration of water into the interface between MoS2/PMMA and substrate due to their different surface energies (Supplementary Fig. 11); finally, inclining the PMMA/MoS2/glass inside a container and injecting water at an optimized rate of 10 ml s−1 to minimize the interface stress. In this way, the 6-inch PMMA/MoS2 film can be easily delaminated from the glass substrate, mainly relying on the interfacial capillary force (Fig. 5b). Finally, the PMMA/MoS2 film was fished by the target substrate and then immersed in acetone to remove PMMA (Fig. 5c). Interestingly, the entire peel-off process can be completed within 60 s for a 6-inch MoS2 film. Directly injecting water rather than gradually feeding the sample into water is much easier to handle and is more suitable for transferring large-area samples.

Green transfer process and device performance of monolayer MoS2. a Schematic diagram of the PMMA-assisted etching-free transfer process onto rigid substrates. b Photograph of the delamination process for removing the PMMA/MoS2 film from the glass substrate. c Photograph of the 6-inch MoS2 film transferred onto a SiO2/Si substrate. d Schematic diagram of the roll-to-roll transfer route onto flexible substrates. e Photograph of a typical 6-inch uniform, flexible, monolayer MoS2/EVA/PET stack. f IDS–VG curves of a typical MoS2 FET device at VDS = 1 V

Compared to the PMMA-assisted transfer route, the developed roll-to-roll method was more convenient as follows: adhesion of EVA/PET plastic onto MoS2/glass via a portable hot lamination process, which is also used to transfer graphene48; immersion of the EVA/PET/MoS2/glass into the deionized water, thus induces automatically penetration of water into the interface between PET/EVA/MoS2 and the glass substrate, followed with effective delamination within 5 min for a 6-inch sample (Fig. 5e).

Notably, both the PMMA-assisted and roll-to-roll transfer pathways are free of acid or alkaline etching, thus avoiding unnecessary contamination and irreversible damage, either to the MoS2 film or to the glass substrate. Accordingly, these carefully designed transfer routes can preserve the original high quality of the CVD-derived monolayer MoS2, and they are more environmentally friendly, efficient, and easier to operate than the commonly used wet chemical etching route. This intact transfer route also guarantees the recyclable use of the glass substrate, as presented in Supplementary Fig. 12 by Raman spectra and OM images. Even so, the soda-lime glass substrate should be used for less than three times considering the gradually decreased Na content on the glass surface.

To evaluate the electrical performance of MoS2 samples, back-gated field-effect transistors (FETs) were fabricated on 300 nm SiO2/Si substrates based on transferred MoS2 monolayers with 10 nm Ti/50 nm Au as source and drain electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 13). The transfer characteristic curve of a typical FET device is presented in Fig. 5f, with a channel length of 1 µm and a channel width of 3 µm, which shows a typical n-type behavior. In addition, the transport characteristics of 46 randomly selected MoS2 FET devices are also analyzed (Supplementary Fig. 13). The achieved mobility and on/off ratio of these devices falls in a narrow range of 6.3 to 11.4 cm2 V−1 s−1 and 105 to106, respectively, suggesting the relative high-quality uniformity of our large-scale MoS2 samples. Both parameters are comparable to those of back-gated FETs fabricated with CVD-grown MoS2 flakes20,24,26,28,32,49,50,51,52 (Supplementary Table 1). Notably, the carrier mobility can be further improved by optimizing the interface contact by pre-treatment24 or changing source/drain electrodes53,54.

Discussion

In summary, by exploiting a face-to-face metal-precursor supply method, we have successfully synthesized a 6-inch uniform monolayer MoS2 film with the domain size larger than 400 µm on solid soda-lime glass. Particularly, the sample size is even scalable by increasing the size of the growth chamber, considering the rather homogenous precursor feeding route designed in this work. Intriguingly, the uniformly distributed Na in soda-lime glass is confirmed to serve as perfect catalysts for the rapid and large-scale uniform growth of monolayer MoS2, according to both experimental facts and DFT calculations. By exploiting the hydrophilicity feature of glass, we have also developed an etching-free method to transfer large-area MoS2 films onto targeted substrates. We believe that this work should pave the way for the cost-effective batch production, environment-friendly transfer, as well as versatile applications in both fundamental and industrial aspects.

Methods

Face-to-face metal-precursor feeding assisted synthesis of macroscopic uniform monolayer MoS2 on soda-lime glass

Before synthesis, the commercial soda-lime glass (14 × 6 cm2; 2 mm thick) was cleaned in deionized water to remove surface impurities. A rectangular piece of Mo foil (99.95%; 0.025 mm thick) was folded into a bridge and placed on top of the soda-lime glass, as shown in Fig. 1a. The Mo foil and glass were placed in a graphite boat and loaded into a 3-inch CVD chamber. Another quartz boat containing sulfur powder (99.5%) was placed upstream, 40 cm away from the substrate. Before heating, the furnace system was purged with 80 sccm Ar for 10 min. Then, Ar (50 sccm) and O2 (6 sccm) gas flows were introduced into the system to create a stable growth atmosphere. The sulfur zone and the substrate zone were heated to 100 and 720 °C within 35 min, respectively. The growth was performed for 8 min to achieve the 6-inch uniform monolayer MoS2 film, and the furnace was then cooled to room temperature automatically.

PMMA-assisted transfer of 6-inch monolayer MoS2 film

Firstly, the as-grown MoS2/glass was spin-coated with PMMA (950 K, Allresist, AR-P 679.04) at a speed of 80 rpm for 1 min followed by curing at 80 °C for 10 min. Then, the edge of PMMA film was scored with a knife to provide a path for the water penetration. Next, the PMMA/MoS2/glass was inclined against the edge of a petri dish, and water was injected with an optimized rate of 10 ml s−1, as shown in Fig. 5a. In this way, the PMMA/MoS2 stack was spontaneously delaminated from glass, and it was then collected by a target substrate. Finally, the PMMA coating was removed using acetone and dried under the flowing N2 gas. For TEM characterizations, the PMMA layer was dissolved with acetone droplets and dried naturally.

Roll-to-roll transfer of monolayer MoS2 film on PET

The 6-inch uniform MoS2 film on soda-lime glass was hot laminated at 180 °C with EVA (50 µm thick) pre-coated with PET (75 µm thick) using a lamination machine to form a glass/MoS2/EVA/PET stack. Then, the glass/MoS2/EVA/PET film was soaked in deionized water for ~5 min. After delamination, the MoS2/EVA/PET stack was dried by flowing N2.

DFT calculations

All calculations were performed adopting the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof55 parametrization for the generalized gradient approximation of the exchange-correlation effect embedded in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package56,57. The ion–electron interaction was described by the projector-augmented wave potentials58,59. Following the kink-flow scheme using a nanoreactor model for graphene60, S2 and Mo were introduced stepwise to the S- or Mo-terminated growth front. The growth fronts were modeled by zigzag nanoribbons of nine lattice units along the periodic direction. The energies of these nanoribbons with and without Na adsorption were taken as references for constructing the energy diagrams. To simplify the discussion, the chemical potential of S was obtained for the most stable sulfur molecule S2 at the growth temperature of 1000 K and partial pressure of 10 kPa, considering their transitional, rotational, and vibrational contributions61. Under such assumptions, the chemical potential of S2 was calculated to be about −10 eV, while those of the bulk material were used for Mo and Na. It should be noted that the choices of chemical potentials did not influence the relative energies for the two cases with and without Na adsorption. The adsorption energies of Na on Mo- and S-terminated edges were calculated as −0.82 and −2.09 eV, indicating their favorable incorporation into the growth fronts.

Characterization of MoS2 films

OM (Nikon ECLIPSE, LV100ND), contact angle measuring system (Dataphysics, OCA20), Raman spectroscopy (HORIBA, LabRAM HR-800, with an excitation wavelength of 514 nm), AFM (Bruker, Dimension Icon), XPS (Kratos Analytical AXIS-Ultra with monochromatic Al Kα X-ray), TEM (JEOL JEM-2100F), STEM (Titan Cubed Themis G2), and ultra high vacuum low temperature (UHV LT) STM were used to characterize the optical and structural properties of the MoS2 sample.

Data availability

The data reported by this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Costanzo, D., Jo, S., Berger, H. & Morpurgo, A. F. Gate-induced superconductivity in atomically thin MoS2 crystals. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 339–344 (2015).

Britnell, L. et al. Strong light–matter interactions in heterostructures of atomically thin films. Science 340, 1311–1314 (2013).

Pospischil, A., Furchi, M. M. & Mueller, T. Solar-energy conversion and light emission in an atomic monolayer p–n diode. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 257–261 (2014).

Chhowalla, M. et al. The chemistry of two-dimensional layered transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheets. Nat. Chem. 5, 263–275 (2013).

Lin, Z. et al. 2D materials advances: from large scale synthesis and controlled heterostructures to improved characterization techniques, defects and applications. 2D Mater. 3, 042001 (2016).

Lopez-Sanchez, O., Lembke, D., Kayci, M., Radenovic, A. & Kis, A. Ultrasensitive photodetectors based on monolayer MoS2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 497–501 (2013).

Saito, Y. et al. Superconductivity protected by spin–valley locking in ion-gated MoS2. Nat. Phys. 12, 144–149 (2016).

Deng, D. et al. Catalysis with two-dimensional materials and their heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 218–230 (2016).

Chen, H. et al. Ultrafast formation of interlayer hot excitons in atomically thin MoS2/WS2 heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 7, 12510 (2016).

Bae, S. et al. Roll-to-roll production of 30-inch graphene films for transparent electrodes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 574–578 (2010).

Muratore, C. et al. Continuous ultra-thin MoS2 films grown by low-temperature physical vapor deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 261604 (2014).

Kang, K. et al. High-mobility three-atom-thick semiconducting films with wafer-scale homogeneity. Nature 520, 656–660 (2015).

Kim, H., Ovchinnikov, D., Deiana, D., Unuchek, D. & Kis, A. Suppressing nucleation in metal-organic chemical vapor deposition of MoS2 monolayers by alkali metal halides. Nano Lett. 17, 5056–5063 (2017).

Gao, Y. et al. Large-area synthesis of high-quality and uniform monolayer WS2 on reusable Au foils. Nat. Commun. 6, 8569 (2015).

Wang, H. High-quality monolayer superconductor NbSe2 grown by chemical vapour deposition. Nat. Commun. 8, 394 (2017).

Zhang, Z. et al. Robust epitaxial growth of two-dimensional heterostructures, multiheterostructures, and superlattices. Science 357, 788–792 (2017).

Zhan, Y., Liu, Z., Najmaei, S., Ajayan, P. M. & Lou, J. Large-area vapor-phase growth and characterization of MoS2 atomic layers on a SiO2 substrate. Small 8, 966–971 (2012).

Wang, X., Feng, H., Wu, Y. & Jiao, L. Controlled synthesis of highly crystalline MoS2 flakes by chemical vapor deposition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 5304–5307 (2013).

Ji, Q., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Liu, Z. Chemical vapour deposition of group-VIB metal dichalcogenide monolayers: engineered substrates from amorphous to single crystalline. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 2587–2602 (2015).

Lee, Y. H. et al. Synthesis of large-area MoS2 atomic layers with chemical vapor deposition. Adv. Mater. 24, 2320–2325 (2012).

Ling, X. et al. Role of the seeding promoter in MoS2 growth by chemical vapor deposition. Nano Lett. 14, 464–472 (2014).

Chen, J. et al. Chemical vapor deposition of large-size monolayer MoSe2 crystals on molten glass. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 1073–1076 (2017).

Chen, J. et al. Homoepitaxial growth of large-scale highly organized transition metal dichalcogenide patterns. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704674 (2018).

Chen, W. et al. Oxygen-assisted chemical vapor deposition growth of large single-crystal and high-quality monolayer MoS2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 15632–15635 (2015).

Ji, Q. et al. Unravelling orientation distribution and merging behavior of monolayer MoS2 domains on sapphire. Nano Lett. 15, 198–205 (2015).

Najmaei, S. et al. Vapour phase growth and grain boundary structure of molybdenum disulphide atomic layers. Nat. Mater. 12, 754–759 (2013).

Wang, S. et al. Shape evolution of monolayer MoS2 crystals grown by chemical vapor deposition. Chem. Mater. 26, 6371–6379 (2014).

van der Zande, A. M. et al. Grains and grain boundaries in highly crystalline monolayer molybdenum disulphide. Nat. Mater. 12, 554–561 (2013).

Yun, S. J. et al. Synthesis of centimeter-scale monolayer tungsten disulfide film on gold foils. ACS Nano 9, 5510–5519 (2015).

Aljarb, A. et al. Substrate lattice-guided seed formation controls the orientation of 2D transition metal dichalcogenides. ACS Nano 11, 9215–9222 (2017).

Chen, Y. et al. Growing uniform graphene disks and films on molten glass for heating devices and cell culture. Adv. Mater. 27, 7839–7846 (2015).

Ju, M. et al. Universal substrate-trapping strategy to grow strictly monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides crystals. Chem. Mater. 29, 6095–6103 (2017).

Li, H., Li, Y., Aljarb, A., Shi, Y. & Li, L. J. Epitaxial growth of two-dimensional layered transition-metal dichalcogenides: growth mechanism, controllability, and scalability. Chem. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00212 (2017).

Zhao, Y. et al. Interlayer breathing and shear modes in few-trilayer MoS2 and WSe2. Nano Lett. 13, 1007–1015 (2013).

Frey, G. L., Tenne, R., Matthews, M. J., Dresselhaus, M. S. & Dresselhaus, G. Raman and resonance Raman investigation of MoS2 nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. B 60, 2883–2892 (1999).

Shi, J. et al. Controllable growth and transfer of monolayer MoS2 on Au foils and its potential application in hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Nano 8, 10196–10204 (2014).

Cong, C. et al. Synthesis and optical properties of large-area single-crystalline 2D semiconductor WS2 monolayer from chemical vapor deposition. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2, 131–136 (2014).

Liu, K. et al. Growth of large-area and highly crystalline MoS2 thin layers on insulating substrates. Nano Lett. 12, 1538–1544 (2012).

Lu, X. et al. Large-area synthesis of monolayer and few-layer MoSe2 films on SiO2 substrates. Nano Lett. 14, 2419–2425 (2014).

Shi, M. L. et al. Top-down integration of molybdenum disulfide transistors with wafer-scale uniformity and layer controllability. Small 13, 1603157 (2017).

Song, J. et al. Layer-controlled, wafer-scale, and conformal synthesis of tungsten disulfide nanosheets using atomic layer deposition. ACS Nano 7, 11333–11340 (2013).

Huang, J. et al. Large-area synthesis of highly crystalline WSe2 monolayers and device applications. ACS Nano 8, 923–930 (2014).

Zhou, H. et al. Large area growth and electrical properties of p-type WSe2 atomic layers. Nano Lett. 15, 709–713 (2015).

Gong, Y. et al. Synthesis of millimeter-scale transition metal dichalcogenides single crystals. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 2009–2015 (2016).

Shi, J. et al. All chemical vapor deposition synthesis and intrinsic bandgap observation of MoS2/Graphene heterostructures. Adv. Mater. 27, 7086–7092 (2015).

Gurarslan, A. et al. Surface-energy-assisted perfect transfer of centimeter-scale films onto arbitrary substrates. ACS Nano 8, 11522–11528 (2014).

Xu, Z. Q. et al. Synthesis and transfer of large-area monolayer WS2 crystals: moving toward the recyclable use of sapphire substrates. ACS Nano 9, 6178–6187 (2015).

Chandrashekar, B. N. et al. Roll-to-roll green transfer of CVD graphene onto plastic for a transparent and flexible triboelectric nanogenerator. Adv. Mater. 27, 5210–5216 (2015).

Liu, B. et al. High-performance chemical sensing using Schottky-contacted chemical vapor deposition grown monolayer MoS2 transistors. ACS Nano 8, 5304–5314 (2014).

Lee, Y.-H. et al. Synthesis and transfer of single-layer transition metal disulfides on diverse surfaces. Nano Lett. 13, 1852–1857 (2013).

Han, G. et al. Seeded growth of highly crystalline molybdenum disulphide monolayers at controlled locations. Nat. Commun. 6, 6128 (2015).

Sun, L. et al. Concurrent synthesis of high-performance monolayer transition metal disulfides. Adv. Funct. Mater. 6, 1605896 (2017).

Das, S., Chen, H. Y., Penumatcha, A. V. & Appenzeller, J. High performance multilayer MoS2 transistors with scandium contacts. Nano Lett. 13, 100–105 (2013).

Radisavljevic, B., Radenovic, A., Brivio, J., Giacometti, I. V. & Kis, A. Single-layer MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 147–150 (2011).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Artyukhov, V. I., Liu, Y. & Yakobson, B. I. Equilibrium at the edge and atomistic mechanisms of graphene growth. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 15136–15140 (2012).

Zou, X., Liu, M., Shi, Z. & Yakobson, B. I. Environment-controlled dislocation migration and superplasticity in monolayer MoS2. Nano Lett. 15, 3495–3500 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 51290272, 51472008, 61774003, and 11327902), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Nos. 2016YFA0200103, 2017YFA0304600, and 2017YFA0205700), the Open Research Fund Program of the State Key Laboratory of Low-Dimensional Quantum Physics (No. KF201601), the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (No. Z161100002116020), the Youth 1000-Talent Program of China, the Shenzhen Basic Research Project (No. JCYJ20170407155608882), and the Development and Reform Commission of Shenzhen Municipality for the development of the “Low-Dimensional Materials and Devices” Discipline. The authors also acknowledge the Electron Microscopy Laboratory in Peking University for the use of Cs corrected electron microscope.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. proposed and supervised the project; P.Y. and Y.Z. designed the experiments; P.Y. performed the large-area uniform MoS2 film synthesis and transfer experiments, and did the OM, Raman, AFM, and XPS measurement; Z.Z. conducted TEM measurement and prepared the STEM sample; M.H. conducted the STM characterizations and data analysis; S.C. and P.G. conducted the STEM measurement; J.S. and Q.C. fabricated devices on SiO2/Si and carried out the electrical properties measurement; L.Z. and Q.Z. did the Raman mapping measurement; X.Z. performed DFT calculations; P.Y. and Y.Z. wrote the manuscript; All the authors contributed to the results analysis and discussions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, P., Zou, X., Zhang, Z. et al. Batch production of 6-inch uniform monolayer molybdenum disulfide catalyzed by sodium in glass. Nat Commun 9, 979 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03388-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03388-5

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.