Abstract

Amine-containing solids have been investigated as promising adsorbents for CO2 capture, but the low oxidative stability of amines has been the biggest hurdle for their practical applications. Here, we developed an extra-stable adsorbent by combining two strategies. First, poly(ethyleneimine) (PEI) was functionalized with 1,2-epoxybutane, which generates tethered 2-hydroxybutyl groups. Second, chelators were pre-supported onto a silica support to poison p.p.m.-level metal impurities (Fe and Cu) that catalyse amine oxidation. The combination of these strategies led to remarkable synergy, and the resultant adsorbent showed a minor loss of CO2 working capacity (8.5%) even after 30 days aging in O2-containing flue gas at 110 °C. This corresponds to a ~50 times slower deactivation rate than a conventional PEI/silica, which shows a complete loss of CO2 uptake capacity after the same treatment. The unprecedentedly high oxidative stability may represent an important breakthrough for the commercial implementation of these adsorbents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) has been investigated as an important option to reduce anthropogenic CO2 emissions1,2. CO2 adsorption using aqueous amine solutions (e.g., monoethanolamine) is considered a benchmark technology for postcombustion CO2 capture3. However, despite the several decades of optimization, the technology still has inherent limitations including volatile amine loss, reactor corrosion, and the high energy consumption for regeneration1,4,5. To overcome these limitations, solid adsorbents that are noncorrosive and can lower the energy consumption have emerged as potential alternatives1,6,7,8. Among various adsorbents, amine-containing solids are considered to be the most promising adsorbents because of high CO2 adsorption selectivity in a typical flue gas containing dilute CO2 (<15% CO2)6,7,8. Such materials can be prepared by the heterogenization of amines in porous supports via the impregnation of polymeric amines such as poly(ethyleneimine) (PEI)9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29, the grafting of aminosilanes14,20,23,24,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39, or the polymerization of amine monomers within the support pores14,20,39,40.

For commercial implementation of adsorbents, they should be stable upon repeated CO2 adsorption–desorption cycles over a long period. Generally, the low adsorbent stability necessitates the continuous addition of fresh adsorbents, which significantly increases the material cost for CO2 capture. Amine-containing adsorbents are known to degrade via various chemical pathways including the oxidative degradation of amines15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,30,31,32,33, urea formation under the CO2-rich atmosphere21,22,23,24,25,33,34,35, steam-induced degradation of the porous supports20,26,27,28, and irreversible adsorption of SO229,37,38. Aside from the oxidative degradation of amines, various solutions have been proposed for suppressing the degradation pathways. For instance, urea formation can be inhibited by selectively using secondary amines rather than primary amines24,34 or injecting steam during adsorbent regeneration14,22,23,28. Steam-induced degradation can be solved by using porous supports with enhanced hydrothermal stability26,27,28. In addition, the amine poisoning by SO2 can be avoided by employing advanced desulfurization unit before CO2 capture41. Therefore, the oxidative degradation of amines remains the biggest hurdle for the practical applications of these adsorbents.

The most ubiquitous impurity in flue gas is O2 (3–4%)1. Unfortunately, in the presence of O2, the amine-containing adsorbents undergo rapid deactivation because of amine oxidation15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,30,31,32,33. Amine oxidation is known to proceed via free radical formation by the reaction of O2 with amines at elevated temperatures42,43,44. The oxidation rate significantly depends on the amine structures. The isolated primary amines are known to be more stable than the isolated secondary amines30,31. In the case of PEI, the linear PEI mainly containing secondary amines is more stable than the branched PEI with a mixture of primary, secondary, and tertiary amines16. The results indicated that the co-existence of different types of amines can affect the oxidative degradation of amines. The polymers with only distant primary amines such as poly(allylamine) are more stable than conventional PEI17. Recently, the use of propylene spacers between amine groups has been found to substantially increase amine stability compared with the PEI containing ethylene spacers18. It has also been reported that the addition of poly(ethylene glycol) into polymeric amines can retard the amine oxidations due to hydrogen bonds between the hydroxy groups of poly(ethylene glycol) and the amines15. Despite these efforts, it still remains a great challenge to improve the oxidative stability of amines to a commercially meaningful level (i.e., stable over several months).

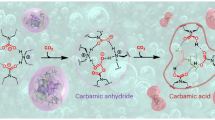

In the present work, we report the synthesis of a modified PEI/silica that shows unprecedentedly high oxidative stability. The adsorbent was prepared by combining two strategies. First, PEI was functionalized with 1,2-epoxybutane (EB), which generates tethered 2-hydroxybutyl groups. Second, small amounts of chelators (<2wt%) were pre-supported into a silica support before the impregnation of functionalized PEI. We discovered that the polymeric amines contain p.p.m.-level metal impurities including Fe and Cu, which catalyse amine oxidation. The addition of chelators as a catalyst poison could significantly suppress the rate of amine oxidation. Notably, the combination of two strategies resulted in great synergy, compared to when each method was used separately.

Results

PEI vs EB-functionalized PEI

The EB-functionalization of PEI (Nippon Shokubai, Epomin SP-012, MW 1200) was carried out as reported previously21 (Fig. 1). We reported that the functionalization can significantly increase the CO2 adsorption kinetics and amine stabilities against urea formation, while it can also retard the amine oxidation to some extent21. 50 wt% of PEI and EB-functionalized PEI (EB-PEI) were supported onto a macroporous silica synthesized by spray-drying a water slurry containing a fumed silica21,26. The silica has a high CO2 accessibility to the supported amines and excellent steam stability arising from its large pore diameter (56 nm in average) and thick framework (10–15 nm)26. The CO2 adsorption–desorption behaviours of PEI/SiO2 and EB-PEI/SiO2 were compared under practical temperature swing adsorption (TSA) conditions; CO2 adsorption was carried out with a simulated flue gas (15% CO2, 10% H2O, N2 balance) at 60 °C and desorption was carried out under 100% CO2 at 110 °C. As shown in Fig. 2a, EB-PEI/SiO2 (1.84 mmol g−1) showed smaller CO2 adsorption than PEI/SiO2 (4.05 mmol g−1) due to the reduced amine density after the EB-functionalization of PEI21. However, the amounts of desorbable CO2 during the adsorbent regeneration (i.e., CO2 working capacities) were similar for both samples (1.98 and 1.62 mmol g−1 for PEI/SiO2 and EB-PEI/SiO2, respectively), because of inefficient CO2 desorption in PEI/SiO2 at 110 °C. The more efficient regeneration of EB-PEI/SiO2 can be attributed to the fact that EB-functionalization lowers the heat of CO2 adsorption by generating tethered 2-hydroxybutyl groups on amines. The functional groups are electron-withdrawing groups that lower the amine basicity and also provide steric hindrance, lowering the heat of CO2 adsorption21. According to differential scanning calorimetry, EB-PEI/SiO2 exhibited a substantially lower heat of CO2 adsorption (66.2 kJ mol−1) than PEI/SiO2 (80.5 kJ mol−1).

Synthesis of oxidation-stable CO2 adsorbent. PEI was functionalized with 1,2-epoxybutane (EB), which generates tethered 2-hydroxybutyl groups. Small amounts of chelators were also pre-supported into a silica support to poison p.p.m.-level metal impurities in the polymeric amines that can catalyse the oxidative degradation of amines

Comparison of the CO2 adsorption–desorption behaviours and oxidative stabilities of PEI/SiO2 and EB-PEI/SiO2. a CO2 adsorption–desorption profiles of the fresh adsorbents (adsorption: 15% CO2, 10% H2O, in N2 balance at 60 °C; desorption: 100% CO2 at 110 °C). b CO2 working capacities before and after the oxidative aging under 3% O2 in N2 at 110 °C for 1 day

The CO2 working capacities of PEI/SiO2 and EB-PEI/SiO2 before and after oxidative aging under 3% O2 in N2 at 110 °C for 24 h are shown in Fig. 2b. The adsorbents were aged at the adsorbent regeneration temperature (110 °C), because it is the highest temperature the adsorbents can experience in TSA. PEI/SiO2 showed a 52% decrease in CO2 working capacity after aging, whereas EB-PEI/SiO2 showed only a 23% decrease. These results show that the EB-functionalization of PEI can increase the oxidative stability of amines, which is consistent with our earlier results21. The EB-functionalization converts the majority of the primary amines in PEI to secondary amines by alkylation with 2-hydroxybutyl groups. 13C NMR analysis showed that the primary:secondary:tertiary amine ratio in PEI is 36:37:27, whereas EB-PEI has a 10:56:34 ratio21. As Sayari pointed out, the oxidative degradation of amines in the PEI-type polymers is significantly affected by the co-existence of different types of amines16. Therefore, the increased stability of EB-PEI/SiO2 might originate from the increased portion of secondary amines at the expense of primary amines. Alternatively, it can also be attributed to the generation of abundant hydroxy (−OH) groups after EB-functionalization, which can form hydrogen bonds with nearby amines. Chuang et al. reported that oxidative stability of amines could be improved in the presence of additives containing hydroxy groups (e.g., polyethylene glycol) because of their abilities to form hydrogen bonds with amines15. FT-IR spectra (Supplementary Fig. 1) showed that N-H stretching bands (3360 and 3290 cm−1) became significantly broadened and the intensity of shoulder at 3160 cm−1 increased after the EB-functionalization of PEI, which could be attributed to the presence of amines hydrogen-bonded with hydroxy groups15.

Poisoning of metal impurities in amines

By coincidence, we discovered that the commercial PEI contains p.p.m.-level transition metal impurities, mainly Fe (17 p.p.m.) and Cu (6.9 p.p.m.) (Supplementary Table 1). Therefore, the EB-functionalized PEI had a more or less similar metal impurity content (Supplementary Table 1). Even though their concentrations are small, these metal species are known to catalyse amine oxidation by facilitating free radical formation via reaction with amines42,43,44. The Fe3+/Fe2+ and Cu2+/Cu+ redox cycles can oxidize amines to form amine radicals via single electron transfer42,43,44, which can significantly increase the amine oxidation rate. The catalytic effects of these metal species on amine oxidation have been comprehensively investigated in the case of aqueous amine solutions, because Fe ions are continuously leached out by reactor corrosion and Cu ions are often deliberately added into the amine solutions to inhibit reactor corrosion42,43,44. However, in the case of solid adsorbents, possible contamination of commercial amine sources with these metal impurities and their catalytic effects on amine oxidation have been completely ignored.

To study the catalytic effects of the metal impurities on amine oxidation, we pre-supported six different types of chelators (Fig. 3a) as catalyst poisons onto a silica support. Then, the silicas were further impregnated with PEI and EB-PEI (Fig. 1). The ionic chelators were not soluble in the polymeric amines (PEI and EB-PEI) and thus needed to be pre-dispersed on the silica surface to maximize their interaction with metal impurities. Because we introduced minor amounts of chelators (<2 wt% per composite), the CO2 working capacities of the adsorbents were not affected by the presence of the chelators (Supplementary Tables 2, 3). All chelators were effective in inhibiting amine oxidation (Fig. 3b, c). As the loading of chelators increased, more CO2 working capacities were retained after oxidative aging. Among the various chelators, phosphate or phosphonate sodium salts (1–3 in Fig. 3a) were the most effective at inhibiting amine oxidation in both PEI (Fig. 3b) and EB-PEI (Fig. 3c) systems. Notably, trisodiumphosphate (TSP, 1 in Fig. 3a), which is a completely inorganic and very economic chelator, showed the most promising inhibition effect. This is practically important because organic chelators themselves are known to be oxidatively degraded in the presence of oxygen and metal species45. This is why organic chelators are not generally regarded as good oxidation inhibitors in aqueous amine solutions44. Interestingly, TSP is known as a weak chelator that is ineffective in poisoning metal impurities in aqueous amine solutions44. We believe that even the TSP could efficiently poison the metal impurities in the solid adsorbents, because of the larger formation constant of corresponding metal phosphates in less polar polymeric amines (i.e., PEI and EB-PEI) than water. It has been reported that the formation constants of various metal complexes increase with decreasing solvent polarity46.

Poisoning of metal impurities using chelators and its retardation effects on amine degradation. a Types of chelators. b, c Retained CO2 working capacity (%) of PEI/SiO2 (b) and EB-PEI/SiO2 (c) containing different amounts of chelators after oxidative aging under 3% O2 in N2 at 110 °C for 1 day. The numbers on plots indicate the types of chelators shown in a

Long-term oxidative stabilities of adsorbents

Because a real flue gas contains CO2 and H2O in addition to O2, the adsorbents must be stable under this atmosphere rather than under an O2/N2 mixed gas. Sayari thoughtfully pointed out that amine oxidation is slower in a real flue gas than in O2/N2 mixtures, because of the preferential interaction of amines with CO2 and H2O22. As shown in Fig. 4, we also confirmed that the addition of CO2 and/or H2O can substantially retard amine oxidation in both of PEI/SiO2 and EB-PEI/SiO2 systems containing varied amounts of TSP. This means that the earlier aging experiments (Figs. 2 and 3) under 3% O2 in N2 should be considered as accelerated aging because they were carried out in the absence of CO2 and H2O. Therefore, to evaluate the long-term stability in a more realistic condition, we analysed the CO2 working capacities of adsorbents after aging in an O2-containing flue gas (3% O2, 15% CO2, 10% H2O in N2 balance) for 30 days.

To separately understand the effects of EB-functionalization and TSP addition on long-term oxidative stabilities, four adsorbents, i.e., PEI/SiO2 and EB-PEI/SiO2 prepared with and without 2 wt% TSP, were investigated (Fig. 5a). Fitting with the first-order deactivation kinetics (trend lines in Fig. 5a) showed that each of the EB-functionalization of PEI (EB-PEI/SiO2) and the TSP addition into PEI (PEI/SiO2 + 2 wt% TSP) could reduce the deactivation rate constant (kdeac) approximately to half (0.0546–0.0573 day−1), compared to that of PEI/SiO2 (0.123 day−1). Notably, the combination of both strategies (EB-PEI/SiO2 + 2 wt% TSP) led to remarkable synergy, and the kdeac (0.00258 day−1) became ~50 times smaller than that of PEI/SiO2. The adsorbent retained 91.5% of the initial CO2 working capacity after 30-days aging, while PEI/SiO2 showed a complete loss of CO2 capacity. The great synergy between the EB-functionalization and TSP addition was attributed to the lower polarity of EB-PEI than that of PEI due to the presence of ethyl side groups (Fig. 1), which can increase the formation constants of metal phosphates (i.e., stronger poisoning of metal species). Our adsorption experiments showed that EB-PEI/SiO2 adsorbed much less H2O (0.7 wt%) than PEI/SiO2 (4.7 wt%) under the simulated flue gas at 60 °C, which proved the lower polarity of EB-PEI.

Long-term oxidative stabilities of adsorbents. a Retained CO2 working capacity (%) of PEI/SiO2 and EB-PEI/SiO2 prepared with and without 2 wt% trisodiumphosphate (TSP) after aging under 3% O2, 15% CO2, 10% H2O in N2 balance at 110 °C. The trend lines are obtained by fitting with the first-order deactivation model. b FT-IR spectra of PEI/SiO2 without TSP and EB-PEI/SiO2 with 2 wt% TSP, before and after 30-days aging

In FT-IR spectra (Fig. 5b), PEI/SiO2 without TSP showed a marked increase in C = O/C = N stretching bands (1670 cm−1) and a decrease in C−H stretching band (2800–3000 cm−1) after the 30-days aging. The result indicates the formation of amide/imine species15,18,19,22. We also found that PEI/SiO2 lost 60% of the initial nitrogen content after the oxidative aging (Supplementary Fig. 2), which could be attributed to the hydrolysis of terminal imines to produce NH342,43. Notably, carbon content also substantially decreased (32%), which indicated a substantial polymer loss from the adsorbent. This implies that oxidation can partly cleave the polymer backbone into smaller fragments, which can be thermally evaporated. The chain degradation may be the consequence of complex amine oxidation reactions. It has been proposed that the ethylenediamine unit of PEI can be decomposed by oxidation into formamide and hemi-aminal47, which can subsequently be decomposed into formic acid, amines, and imines. Alternatively, the imines generated at the middle of the polymer backbone can be hydrolysed to produce amine and aldehydes, which can also result in chain cleavage. Based on these results, it can be concluded that the oxidation of polymeric amines can lead to the loss of CO2 capacity for two reasons: (1) the conversion of basic amines into non-basic amide/imine species, and (2) the accelerated loss of polymeric amines by oxidative fragmentation. In contrast, EB-PEI/SiO2 with 2 wt% TSP exhibited insubstantial change in FT-IR spectrum after aging. Furthermore, the decreases in nitrogen and carbon contents were insignificant (<6.2%).

Discussion

We synthesized oxidation-stable amine-containing adsorbents via the functionalization of PEI with 1,2-epoxybutane (EB) and the poisoning of the p.p.m.-level metal impurities with chelators. The combination of two different strategies could make remarkable synergy, because chelators form metal complexes more efficiently (i.e., stronger poisoning) in less polar EB-functionalized PEI. We believe that the amine-containing solid adsorbent is beneficial in terms of oxidative stability compared to conventional aqueous amine solutions, because the aqueous amine solutions cause the continuous leaching of metal species by reactor corrosion and these metals act as catalysts for amine oxidation. This requires the continuous and stoichiometric addition of inhibitors such as oxygen/radical scavengers or chelators, and also the removal of their decomposition products44. In the case of solid adsorbents, the initial poisoning of the p.p.m.-level metal impurities in polymeric amines is sufficient to increase the oxidative stability over a long period because there is no continuous metal buildup from reactor corrosion. Furthermore, the polymeric amines less polar than water can also enable more efficient metal poisoning by chelators. The unprecedentedly high oxidative stability of amine-containing solid adsorbents may represent an important breakthrough toward their commercial implementation.

Methods

Functionalization of PEI with 1,2-epoxybutane (EB)

EB-functionalization of a commercial PEI (Nippon Shokubai, Epomin SP-012, MW 1200) was carried out as we reported previously21. In a typical synthesis, 12 g of 1,2-epoxybutane (Sigma-Aldrich, 99%) was added dropwise to 60 g of a 33 wt% methanolic solution of PEI. The molar ratio between 1,2-epoxybutane and the nitrogen content in PEI (22 mmolN g−1) was fixed at 0.37. The reaction was carried out at room temperature for 12 h with stirring. The resultant methanolic solution containing 44 wt% EB-PEI was directly used for impregnation into a silica support.

Preparation of a macroporous silica support

A highly macroporous silica support was prepared following the procedure we reported previously21,26. The silica was synthesized by spray-drying a water slurry containing 9.5 wt% fumed silica (OCI, KONASIL K-300) and 0.5 wt% silica sol (Aldrich, Ludox AS-30) as a binder. In a typical synthesis, 0.95 kg fumed silica, 0.05 kg silica sol, and 9 kg water were mixed and the resultant slurry was injected for spray-drying. The spray-drying was carried out using a spray dryer with a co-current drying configuration and a rotary atomizer (Zeustec ZSD-25). The injection rate was 30 cm3 min−1, and the rotating speed of the rotary atomizer was set to 4000 r.p.m. The air blowing inlet temperature was 210 °C and the outlet temperature was 150 °C. The resultant silica particles were calcined in dry air at 600 °C to sinter the fumed silica into a three-dimensional porous network.

Impregnation of chelators into the silica support

In the present work, chelators in a completely basic form (all acidic functional groups were titrated with Na+) were impregnated into the macroporous silica support using their aqueous solutions (typically, 0.25–2.0 wt% chelator concentrations). For the preparation of the aqueous solutions, trisodiumphosphate (1 in Fig. 3a, Sigma Aldrich, 96%) and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tetrasodium salt dihydrate (4, Sigma Aldrich, 99%) were directly dissolved in deionized water. In the cases of chelators in an acidic form, such as 1-hydroxyethane 1,1-diphosphonic acid monohydrate (2, Sigma Aldrich, 95%), ethylenediamine tetramethylene phosphonic acid (3, Tokyo Chemical Industry, 98%), diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (5, Sigma Aldrich, 99%), and meso-2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid (6, Sigma Aldrich, 98%), controlled amounts of NaOH were dissolved together in deionized water to completely titrate acidic H+ into Na+. After the wet impregnation of the chelators into the silica support, the samples were dried in a vacuum oven at 100 °C for 12 h. The final loading of chelators was controlled in the range of 0–4 wt% with respect to the mass of silica support.

Preparation of the PEI/SiO2 and EB-PEI/SiO2 adsorbents

Methanolic solutions of PEI and EB-PEI were impregnated into the macroporous silica supports pre-impregnated with 0–4 wt% chelators. After impregnation, the samples were dried at 60 °C for 12 h in a vacuum oven to remove methanol completely. With respect to the mass of the final composite adsorbents, the polymer content was fixed to 50 wt% and the chelator content was controlled in the range of 0–2 wt%.

Material characterization

The heat of CO2 adsorption was measured by differential scanning calorimetry (Setaram Instrumentation, Setsys Evolution). Before the measurements, the samples were degassed at 100 °C for 1 h under N2 flow (50 cm3 min−1). Then, the samples were cooled to 60 °C. Subsequently, the gas was switched to 15% CO2 (50 cm3 min−1). The heat of adsorption was calculated through the integration of the heat flow curve. Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were recorded using an FT-IR spectrometer (Thermo Nicolet NEXUS 470). Prior to the analysis, 3 mg of the adsorbents were grinded with 18 mg of the silica (macroporous silica support) as a diluent. The mixtures were pressed into a self-supporting wafer. Before the FT-IR measurements, each sample was degassed at 100 °C for 3 h under vacuum in an in situ infrared cell equipped with CaF2 windows. FT-IR spectra were collected at room temperature. Elemental compositions (C, H, and N) of the adsorbents were analysed using a FLASH 2000 (Thermo Scientific) instrument. The contents of transition metal impurities (Fe, Cu, etc.) in PEI and EB-PEI were determined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS) using an ICP-MS 7700S instrument (Agilent). In the case of EB-PEI, the metal concentrations were determined after the complete evaporation of the methanol solvent at 60 °C for 12 h under vacuum after its synthesis.

CO2 adsorption–desorption experiments

CO2 adsorption–desorption profiles were collected by a thermogravimetric analysis-mass spectrometry (TGA-MS) setup21,35. Prior to the measurements, all samples were degassed at 100 °C for 1 h under N2 flow (50 cm3 min−1). CO2 adsorption was carried out using a simulated wet flue gas containing 15% CO2, 10% H2O, and N2 balance at 60 °C. After 30 min adsorption, the gas was switched to 100% CO2 flow (50 cm3 min−1) and the temperature was increased to 110 °C (ramp: 20 °C min−1). Then the temperature was maintained for 30 min for the desorption process. The adsorbed amount of CO2 was calculated by subtracting the amount of adsorbed H2O (determined by mass spectrometry) from the total mass increase determined by TGA. To confirm the reliability of the TGA-MS results, the CO2 uptake was also cross-checked with an automated chemisorption analyser (Micromeritics, Autochem II 2920) specially equipped with a cold trap (−10 °C) for H2O removal in front of the TCD detector21,35.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

D’Alessandro, D. M., Smit, B. & Long, J. R. Carbon dioxide capture: prospects for new materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 6058–6082 (2010).

Haszeldine, R. S. Carbon capture and storage: how green can black be? Science 325, 1647–1652 (2009).

Rochelle, G. T. Amine scrubbing for CO2 capture. Science 325, 1652–1654 (2009).

Figueroa, J. D., Fout, T., Plasynski, S., McIlvried, H. & Srivastava, R. D. Advances in CO2 capture technology–the U.S. department of energy’s carbon sequestration program. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 2, 9–20 (2008).

Nguyen, T., Hilliard, M. & Rochelle, G. T. Amine volatility in CO2 capture. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 4, 707–715 (2010).

Wang, J. et al. Recent advances in solid sorbents for CO2 capture and new development trends. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 3478–3518 (2014).

Choi, S., Drese, J. H. & Jones, C. W. Adsorbent materials for carbon dioxide capture from large anthropogenic point sources. ChemSusChem 2, 796–854 (2009).

Bollini, P., Didas, S. A. & Jones, C. W. Amine-oxide hybrid materials for acid gas separations. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 15100–15120 (2011).

Xu, X., Song, C., Andresen, J. M., Miller, B. G. & Scaroni, A. W. Novel polyethylenimine-modified mesoporous molecular sieve of MCM-41 type as high-capacity adsorbent for CO2 capture. Energy Fuels. 16, 1463–1469 (2002).

Xu, X., Song, C., Andrésen, J. M., Miller, B. G. & Scaroni, A. W. Preparation and characterization of novel CO2 “molecular basket” adsorbents based on polymer-modified mesoporous molecular sieve MCM-41. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 62, 29–45 (2003).

Goeppert, A., Meth, S., Prakash, G. K. S. & Olah, G. A. Nanostructured silica as a support for regenerable high-capacity organoamine-based CO2 sorbents. Energy Environ. Sci. 3, 1949–1960 (2010).

Ma, X., Wang, X. & Song, C. “Molecular basket” sorbents for separation of CO2 and H2S from various gas streams. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 5777–5783 (2009).

Qi, G. et al. High efficiency nanocomposite sorbents for CO2 capture based on amine-functionalized mesoporous capsules. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 444–452 (2011).

Li, W. et al. Steam-stripping for regeneration of supported amine-based CO2 adsorbents. ChemSusChem 3, 899–903 (2010).

Srikanth, C. S. & Chuang, S. S. C. Spectroscopic investigation into oxidative degradation of silica-supported amine sorbents for CO2 capture. ChemSusChem 5, 1435–1442 (2012).

Ahmadalinezhad, A. & Sayari, A. Oxidative degradation of silica-supported polyethylenimine for CO2 adsorption: insights into the nature of deactivated species. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 1529–1535 (2014).

Bali, S., Chen, T. T., Chaikittisilp, W. & Jones, C. W. Oxidative stability of amino polymer-alumina hybrid adsorbents for carbon dioxide capture. Energy Fuels. 27, 1547–1554 (2013).

Pang, S. H., Lee, L. C., Sakwa-Novak, M. A., Lively, R. P. & Jones, C. W. Design of amino polymer structure to enhance performance and stability of CO2 sorbents: poly(propylenimine) vs poly(ethylenimine). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 3627–3630 (2017).

Srikanth, C. S. & Chuang, S. S. C. Infrared study of strongly and weakly adsorbed CO2 on fresh and oxidatively degraded amine sorbents. J. Phys. Chem. C. 117, 9196–9205 (2013).

Li, W. et al. Structural changes of silica mesocellular foam supported amine-functionalized CO2 adsorbents upon exposure to steam. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2, 3363–3372 (2010).

Choi, W. et al. Epoxide-functionalization of polyethyleneimine for synthesis of stable carbon dioxide adsorbent in temperature swing adsorption. Nat. Commun. 7, 12640 (2016).

Heydari-Gorji, A. & Sayari, A. Thermal, oxidative, and CO2-induced degradation of supported polyethylenimine adsorbents. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 51, 6887–6894 (2012).

Sayari, A. & Belmabkhout, Y. Stabilization of amine-containing CO2 adsorbents: dramatic effect of water vapor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 6312–6314 (2010).

Sayari, A., Heydari-Gorji, A. & Yang, Y. CO2-induced degradation of amine-containing adsorbents: reaction products and pathways. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 13834–13842 (2012).

Drage, T. C., Arenillas, A., Smith, K. M. & Snape, C. E. Thermal stability of polyethylenimine based carbon dioxide adsorbents and its influence on selection of regeneration strategies. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 116, 504–512 (2008).

Min, K., Choi, W. & Choi, M. Macroporous silica with thick framework for steam-stable and high-performance poly(ethyleneimine)/silica CO2 adsorbent. ChemSusChem 10, 2518–2526 (2017).

Chaikittisilp, W., Kim, H. J. & Jones, C. W. Mesoporous alumina-supported amines as potential steam-stable adsorbents for capturing CO2 from simulated flue gas and ambient air. Energy Fuels. 25, 5528–5537 (2011).

Hammache, S. et al. Comprehensive study of the impact of steam on polyethyleneimine on silica for CO2 capture. Energy Fuels. 27, 6899–6905 (2013).

Rezaei, F. & Jones, C. W. Stability of supported amine adsorbents to SO2 and NOx in postcombustion CO2 capture. 1. Single-component adsorption. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 52, 12192–12201 (2013).

Bollini, P., Choi, S., Drese, J. H. & Jones, C. W. Oxidative degradation of aminosilica adsorbents relevant to postcombustion CO2 capture. Energy Fuels. 25, 2416–2425 (2011).

Heydari-Gorji, A., Belmabkhout, Y. & Sayari, A. Degradation of amine-supported CO2 adsorbents in the presence of oxygen-containing gases. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 145, 146–149 (2011).

Ahmadalinezhad, A., Tailor, R. & Sayari, A. Molecular-level insights into the oxidative degradation of grafted amines. Chem. Eur. J. 19, 10543–10550 (2013).

Didas, S. A., Zhu, R., Brunelli, N. A., Sholl, D. S. & Jones, C. W. Thermal, oxidative and CO2 induced degradation of primary amines used for CO2 capture: effect of alkyl linker on stability. J. Phys. Chem. C. 118, 12302–12311 (2014).

Sayari, A., Belmabkhout, Y. & Da’na, E. CO2 deactivation of supported amines: does the nature of amine matter? Langmuir 28, 4241–4247 (2012).

Kim, C., Cho, H. S., Chang, S., Cho, S. J. & Choi, M. An ethylenediamine-grafted Y zeolite: a highly regenerable carbon dioxide adsorbent via temperature swing adsorption without urea formation. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 1803–1811 (2016).

McDonald, T. M. et al. Cooperative insertion of CO2 in diamine-appended metal-organic frameworks. Nature 519, 303–308 (2015).

Khatri, R. A., Chuang, S. S. C., Soong, Y. & Gray, M. Thermal and chemical stability of regenerable solid amine sorbent for CO2 capture. Energy Fuels. 20, 1514–1520 (2006).

Belmabkhout, Y. & Sayari, A. Isothermal versus non-isothermal adsorption–desorption cycling of triamine-grafted pore-expanded MCM-41 mesoporous silica for CO2 capture from flue gas. Energy Fuels. 24, 5273–5280 (2010).

Qi, G., Fu, L. & Giannelis, E. P. Sponges with covalently tethered amines for high-efficiency carbon capture. Nat. Commun. 5, 5796 (2014).

Hicks, J. C. et al. Designing adsorbents for CO2 capture from flue gas-hyperbranched aminosilicas capable of capturing CO2 reversibly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 2902–2903 (2008).

Rao, A. B. & Rubin, E. S. A technical, economic, and environmental assessment of amine-based CO2 capture technology for power plant greenhouse gas control. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36, 4467–4475 (2002).

Chi, S. & Rochelle, G. Oxidative degradation of monoethanolamine. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 41, 4178–4186 (2002).

Goff, G. S. & Rochelle, G. T. Monoethanolamine degradation: O2 mass transfer effects under CO2 capture conditions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 43, 6400–6408 (2004).

Goff, G. S. & Rochelle, G. T. Oxidation inhibitors for copper and iron catalyzed degradation of monoethanolamine in CO2 capture processes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 45, 2513–2521 (2006).

Seibig, S. & van Eldik, R. Kinetics of [FeII(edta)] oxidation by molecular oxygen revisited. New evidence for a multistep mechanism. Inorg. Chem. 36, 4115–4120 (1997).

Mui, K.-K., Mcbryde, W. A. E. & Nieboer, E. The stability of some metal complexes in mixed solvents. Can. J. Chem. 52, 1821–1833 (1974).

Idris, S. A., Mkhatresh, O. A. & Heatley, F. Assignment of 1H NMR spectrum and investigation of oxidative degradation of poly(ethylenimine) using 1H and 13C 1-D and 2-D NMR. Polym. Int. 55, 1040–1048 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Korea CCS R&D Center (KCRC) grant funded by the Korea government (Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning) (NRF-2014M1A8A1049256) and the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2017R1A2B2002346).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C. conceived and designed this study. K.M., W.C., and C.K. performed material synthesis, characterizations, and CO2 adsorption–desorption experiments. M.C. wrote the manuscript with assistance from K.M., W.C., and C.K. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Min, K., Choi, W., Kim, C. et al. Oxidation-stable amine-containing adsorbents for carbon dioxide capture. Nat Commun 9, 726 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03123-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03123-0

This article is cited by

-

Non-solvent post-modifications with volatile reagents for remarkably porous ketone functionalized polymers of intrinsic microporosity

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Development of composite amine functionalized polyester microspheres for efficient CO2 capture

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

-

Indoor carbon dioxide capture technologies: a review

Environmental Chemistry Letters (2023)

-

Shaping and silane coating of a diamine-grafted metal-organic framework for improved CO2 capture

Communications Materials (2021)

-

Porous materials for carbon dioxide separations

Nature Materials (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.