Key Points

-

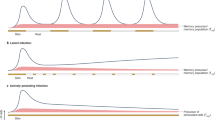

Most markers that define functional subsets of CD8+ T cells are regulated by activation, which complicates their use as differentiation markers.

-

Although during acute infection overall similarities dominate between T cells specific for different viruses, their phenotypes seem to be distinct in the memory/latency stage.

-

Infection with cytomegalovirus has a dominant influence on the circulating CD8+ T-cell pool, promoting the generation and maintenance of a population with stable cytolytic function.

-

Specific co-stimulatory ligands (or cytokines) present during the initial priming or memory/latency stages might direct CD8+ T-cell differentiation and account for differences between T cells that react to different viruses.

Abstract

CD8+ T cells are essential in the defence against viruses. Recently, peptide–HLA class I tetramers have been used to study immune responses to viruses in humans. This approach has indicated consecutive stages of human CD8+ T-cell development in acute viral infection and has illustrated the heterogeneity of CD8+ T cells that are specific for latent viruses. Here, we summarize these findings and discuss their significance for our understanding of antigen-induced CD8+ T-cell maturation in humans.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kaech, S. M., Wherry, E. J. & Ahmed, R. Effector and memory T-cell differentiation: implications for vaccine development. Nature Rev. Immunol. 2, 251–262 (2002).

Wong, P. & Pamer, E. G. CD8+ T cell responses to infectious pathogens. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21, 29–70 (2003).

Murali-Krishna, K. et al. Counting antigen-specific CD8+ T cells: a reevaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity 8, 177–187 (1998).

Berke, G. The CTL's kiss of death. Cell 81, 9–12 (1995).

Badovinac, V. P., Porter, B. B. & Harty, J. T. Programmed contraction of CD8+ T cells after infection. Nature Immunol. 3, 619–626 (2002). This paper shows that not only clonal expansion but also clonal contraction might be determined in the initial contact between a T cell and an antigen-presenting cell (APC).

Kaech, S. M., Hemby, S., Kersh, E. & Ahmed, R. Molecular and functional profiling of memory CD8+ T cell differentiation. Cell 111, 837–851 (2002).

Schluns, K. S. & Lefrancois, L. Cytokine control of memory T-cell development and survival. Nature Rev. Immunol. 3, 269–279 (2003).

Jordan, M. C., Jordan, G. W., Stevens, J. G. & Miller, G. Latent herpesviruses of humans. Ann. Intern. Med. 100, 866–880 (1984).

Marchant, A. et al. Mature CD8+ T lymphocyte response to viral infection during fetal life. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 1747–1755 (2003).

Gray, D. A role for antigen in the maintenance of immunological memory. Nature Rev. Immunol. 2, 60–65 (2002).

Selin, L. K. et al. Attrition of T cell memory: selective loss of LCMV epitope-specific memory CD8 T cells following infections with heterologous viruses. Immunity 11, 733–742 (1999).

Rabin, R. L. et al. Altered representation of naive and memory CD8 T cell subsets in HIV-infected children. J. Clin. Invest. 95, 2054–2060 (1995).

Hamann, D. et al. Phenotypic and functional separation of memory and effector human CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 186, 1407–1418 (1997).

Sallusto, F., Lenig, D., Forster, R., Lipp, M. & Lanzavecchia, A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature 401, 708–712 (1999).

Campbell, J. J. et al. CCR7 expression and memory T cell diversity in humans. J. Immunol. 166, 877–884 (2001).

Merkenschlager, M. & Beverley, P. C. Evidence for differential expression of CD45 isoforms by precursors for memory-dependent and independent cytotoxic responses: human CD8 memory CTLp selectively express CD45RO (UCHL1). Int. Immunol. 1, 450–459 (1989).

Sallusto, F., Cella, M., Danieli, C. & Lanzavecchia, A. Dendritic cells use macropinocytosis and the mannose receptor to concentrate macromolecules in the major histocompatibility complex class II compartment: downregulation by cytokines and bacterial products. J. Exp. Med. 182, 389–400 (1995).

de Jong, R., Brouwer, M., Miedema, F. & Van Lier, R. A. Human CD8+ T lymphocytes can be divided into CD45RA+ and CD45RO+ cells with different requirements for activation and differentiation. J. Immunol. 146, 2088–2094 (1991).

Tomiyama, H., Matsuda, T. & Takiguchi, M. Differentiation of human CD8+ T cells from a memory to memory/effector phenotype. J. Immunol. 168, 5538–5550 (2002).

Reinhardt, R. L., Khoruts, A., Merica, R., Zell, T. & Jenkins, M. K. Visualizing the generation of memory CD4+ T cells in the whole body. Nature 410, 101–105 (2001).

Masopust, D., Vezys, V., Marzo, A. L. & Lefrancois, L. Preferential localization of effector memory cells in nonlymphoid tissue. Science 291, 2413–2417 (2001).

Ravkov, E. V., Myrick, C. M. & Altman, J. D. Immediate early effector functions of virus-specific CD8+CCR7+ memory cells in humans defined by HLA and CC chemokine ligand 19 tetramers. J. Immunol. 170, 2461–2468 (2003).

Wherry, E. J. et al. Lineage relationship and protective immunity of memory CD8+ T cell subsets. Nature Immunol. 4, 225–234 (2003). This paper addresses the lineage relationship between memory T-cell subsets in vivo, providing evidence that central memory cells might develop from effector-memory cells relatively late after clearance of pathogen.

Unsoeld, H., Krautwald, S., Voehringer, D., Kunzendorf, U. & Pircher, H. Cutting edge: CCR7+ and CCR7− memory T cells do not differ in immediate effector cell function. J. Immunol. 169, 638–641 (2002).

Ellefsen, K. et al. Distribution and functional analysis of memory antiviral CD8 T cell responses in HIV-1 and cytomegalovirus infections. Eur. J. Immunol. 32, 3756–3764 (2002).

Azuma, M., Phillips, J. H. & Lanier, L. L. CD28− T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 150, 1147–1159 (1993).

Okumura, M., Fujii, Y., Inada, K., Nakahara, K. & Matsuda, H. Both CD45RA+ and CD45RA− subpopulations of CD8+ T cells contain cells with high levels of LFA-1 expression, a phenotype of primed T cells. J. Immunol. 150, 429–437 (1993).

Pittet, M. J., Speiser, D. E., Valmori, D., Cerottini, J. C. & Romero, P. Cutting edge: cytolytic effector function in human circulating CD8+ T cells closely correlates with CD56 surface expression. J. Immunol. 164, 1148–1152 (2000).

Brenchley, J. M. et al. Expression of CD57 defines replicative senescence and antigen-induced apoptotic death of CD8+ T cells. Blood 101, 2711–2720 (2003).

Speiser, D. E. et al. The activatory receptor 2B4 is expressed in vivo by human CD8+ effector αβ T cells. J. Immunol. 167, 6165–6170 (2001).

Bell, E. B. & Sparshott, S. M. Interconversion of CD45R subsets of CD4 T cells in vivo. Nature 348, 163–166 (1990).

Mingari, M. C. et al. Human CD8+ T lymphocyte subsets that express HLA class I-specific inhibitory receptors represent oligoclonally or monoclonally expanded cell populations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 12433–12438 (1996).

Baars, P. A. et al. Cytolytic mechanisms and expression of activation-regulating receptors on effector-type CD8+CD45RA+. J. Immunol. 165, 1910–1917 (2000).

Murphy, K. M. & Reiner, S. L. The lineage decisions of helper T cells. Nature Rev. Immunol. 2, 933–944 (2002).

van Leeuwen, E. M. et al. Proliferation requirements of cytomegalovirus-specific, effector-type human CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 169, 5838–5843 (2002).

Wierenga, E. A. et al. Human atopen-specific types 1 and 2 T helper cell clones. J. Immunol. 147, 2942–2949 (1991).

Rufer, N. et al. Ex-vivo characterization of human CD8+ T subsets with distinct replicative history and partial effector functions. Blood 105, 1779–1787 (2003).

Altman, J. D. et al. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science 274, 94–96 (1996).

Callan, M. F. et al. Direct visualization of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells during the primary immune response to Epstein–Barr virus in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 187, 1395–1402 (1998).

Callan, M. F. et al. T cell selection during the evolution of CD8+ T cell memory in vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 28, 4382–4390 (1998).

Hislop, A. D., Annels, N. E., Gudgeon, N. H., Leese, A. M. & Rickinson, A. B. Epitope-specific evolution of human CD8+ T cell responses from primary to persistent phases of Epstein–Barr virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 195, 893–905 (2002).

Catalina, M. D., Sullivan, J. L., Brody, R. M. & Luzuriaga, K. Phenotypic and functional heterogeneity of EBV epitope-specific CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 168, 4184–4191 (2002).

Roos, M. T. et al. Changes in the composition of circulating CD8+ T cell subsets during acute Epstein–Barr and human immunodeficiency virus infections in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 182, 451–458 (2000). This reference, together with references 44 and 46, describe longitudinal studies on primary responses to virus in humans.

Appay, V. et al. Dynamics of T cell responses in HIV infection. J. Immunol. 168, 3660–3666 (2002).

Wills, M. R. et al. Identification of naive or antigen-experienced human CD8+ T cells by expression of co-stimulation and chemokine receptors: analysis of the human cytomegalovirus-specific CD8+ T cell response. J. Immunol. 168, 5455–5464 (2002).

Gamadia, L. E. et al. Primary immune responses to human CMV: a critical role for IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells in protection against CMV disease. Blood 101, 2686–2692 (2003).

Thimme, R. et al. Determinants of viral clearance and persistence during acute hepatitis C virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 194, 1395–1406 (2001).

Lechner, F. et al. Analysis of successful immune responses in persons infected with hepatitis C virus. J. Exp. Med. 191, 1499–1512 (2000).

Urbani, S. et al. Virus-specific CD8+ lymphocytes share the same effector-memory phenotype but exhibit functional differences in acute hepatitis B and C. J. Virol. 76, 12423–12434 (2002).

Appay, V. et al. Memory CD8+ T cells vary in differentiation phenotype in different persistent virus infections. Nature Med. 8, 379–385 (2002). Together with reference 51, this study shows the phenotypic differences between virus-specific CD8+ T cells in large cohorts.

Tussey, L. G. et al. Antigen burden is major determinant of human immunodeficiency virus-specific CD8+ T cell maturation state: potential implications for therapeutic immunization. J. Infect. Dis. 187, 364–374 (2003).

Baron, V. et al. The repertoires of circulating human CD8+ central and effector memory T cell subsets are largely distinct. Immunity 18, 193–204 (2003).

Hislop, A. D. et al. EBV-specific CD8+ T cell memory: relationships between epitope specificity, cell phenotype, and immediate effector function. J. Immunol. 167, 2019–2029 (2001).

Geginat, J., Lanzavecchia, A. & Sallusto, F. Proliferation and differentiation potential of human CD8+ memory T-cell subsets in response to antigen or homeostatic cytokines. Blood 101, 4260–4266 (2003).

Alves, N. L., Hooibrink, B., Arosa, F. A. & Van Lier, R. A. IL-15 induces antigen-independent expansion and differentiation of human naive CD8+ T cells in vitro. Blood 102, 2541–2546 (2003)

Kuijpers, T. W. et al. Frequencies of circulating cytolytic, CD45RA+CD27−CD8+ T lymphocytes depend on infection with CMV. J. Immunol. 170, 4342–4348 (2003).

Khan, N. et al. Cytomegalovirus seropositivity drives the CD8 T cell repertoire toward greater clonality in healthy elderly individuals. J. Immunol. 169, 1984–1992 (2002).

Wang, E. C. et al. CD8highCD57+ T lymphocytes in normal, healthy individuals are oligoclonal and respond to human cytomegalovirus. J. Immunol. 155, 5046–5056 (1995).

Kern, F. et al. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) phosphoprotein 65 makes a large contribution to shaping the T cell repertoire in CMV-exposed individuals. J. Infect. Dis. 185, 1709–1716 (2002).

Champagne, P. et al. Skewed maturation of memory HIV-specific CD8 T lymphocytes. Nature 410, 106–111 (2001).

Monteiro, J., Batliwalla, F., Ostrer, H. & Gregersen, P. K. Shortened telomeres in clonally expanded CD28−CD8+ T cells imply a replicative history that is distinct from their CD28+CD8+ counterparts. J. Immunol. 156, 3587–3590 (1996).

Hamann, D. et al. Evidence that human CD8+CD45RA+. Int. Immunol. 11, 1027–1033 (1999).

Posnett, D. N., Sinha, R., Kabak, S. & Russo, C. Clonal populations of T cells in normal elderly humans: the T cell equivalent to 'benign monoclonal gammapathy'. J. Exp. Med. 179, 609–618 (1994).

Hendriks, J. et al. CD27 is required for generation and long-term maintenance of T cell immunity. Nature Immunol. 1, 433–440 (2000).

Arens, R. et al. Constitutive CD27/CD70 interaction induces expansion of effector-type T cells and results in IFN-γ-mediated B cell depletion. Immunity. 15, 801–812 (2001).

Hintzen, R. Q. et al. Regulation of CD27 expression on subsets of mature T-lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 151, 2426–2435 (1993).

McMichael, A. J. & Rowland-Jones, S. L. Cellular immune responses to HIV. Nature 410, 980–987 (2001).

van Baarle, D. et al. Lack of Epstein–Barr virus- and HIV-specific CD27−CD8+ T cells is associated with progression to viral disease in HIV-infection. AIDS 16, 2001–2011 (2002).

Appay, V. & Rowland-Jones, S. L. Premature ageing of the immune system: the cause of AIDS? Trends Immunol. 23, 580–585 (2002).

van Baarle, D., Kostense, S., Van Oers, M. H., Hamann, D. & Miedema, F. Failing immune control as a result of impaired CD8+ T-cell maturation: CD27 might provide a clue. Trends Immunol. 23, 586–591 (2002).

Janssen, E. M. et al. CD4+ T cells are required for secondary expansion and memory in CD8+ T lymphocytes. Nature 421, 852–856 (2003).

Sun, J. C. & Bevan, M. J. Defective CD8+ T cell memory following acute infection without CD4+ T cell help. Science 300, 339–342 (2003).

Shedlock, D. J. & Shen, H. Requirement for CD4 T cell help in generating functional CD8 T cell memory. Science 300, 337–339 (2003).

Riddell, S. R., Reusser, P. & Greenberg, P. D. Cytotoxic T cells specific for cytomegalovirus: a potential therapy for immunocompromised patients. Rev. Infect. Dis. 13 Suppl. 11, S966–S973 (1991).

Lee, P. P. et al. Characterization of circulating T cells specific for tumor-associated antigens in melanoma patients. Nature Med. 5, 677–685 (1999).

Dunbar, P. R. et al. A shift in the phenotype of melan-A-specific CTL identifies melanoma patients with an active tumor-specific immune response. J. Immunol. 165, 6644–6652 (2000).

Fong, L. et al. Altered peptide ligand vaccination with Flt3 ligand expanded dendritic cells for tumor immunotherapy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 8809–8814 (2001).

Trowbridge, I. S. & Thomas, M. L. CD45: an emerging role as a protein tyrosine phosphatase required for lymphocyte activation and development. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 12, 85–116 (1994).

Streuli, M., Hall, L. R., Saga, Y., Schlossman, S. F. & Saito, H. Differential usage of three exons generates at least five different mRNAs encoding human leukocyte common antigens. J. Exp. Med. 166, 1548–1566 (1987).

Smith, S. H., Brown, M. H., Rowe, D., Callard, R. E. & Beverley, P. C. Functional subsets of human helper-inducer cells defined by a new monoclonal antibody, UCHL1. Immunology 58, 63–70 (1986).

Sanders, M. E. et al. Human memory T lymphocytes express increased levels of three cell adhesion molecules (LFA-3, CD2, and LFA-1) and three other molecules (UCHL1, CDw29, and Pgp-1) and have enhanced IFN-γ production. J. Immunol. 140, 1401–1407 (1988).

Novak, T. J. et al. Isoforms of the transmembrane tyrosine phosphatase CD45 differentially affect T cell recognition. Immunity. 1, 109–119 (1994).

Springer, T. A. & Lasky, L. A. Cell adhesion. Sticky sugars for selectins. Nature 349, 196–197 (1991).

Kannagi, R. Regulatory roles of carbohydrate ligands for selectins in the homing of lymphocytes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12, 599–608 (2002).

Janeway, C. A., Jr & Bottomly, K. Signals and signs for lymphocyte responses. Cell 76, 275–285 (1994).

June, C. H., Bluestone, J. A., Nadler, L. M. & Thompson, C. B. The B7 and CD28 receptor families. Immunol. Today 15, 321–331 (1994).

Linsley, P. S., Bradshaw, J., Urnes, M., Grosmaire, L. & Ledbetter, J. A. CD28 engagement by B7/BB-1 induces transient downregulation of CD28 synthesis and prolonged unresponsiveness to CD28 signaling. J. Immunol. 150, 3161–3169 (1993).

Goodwin, R. G. et al. Molecular and biological characterization of a ligand for CD27 defines a new family of cytokines with homology to tumor necrosis factor. Cell 73, 447–456 (1993).

Hintzen, R. Q., de Jong, R., Lens, S. M. & Van Lier, R. A. CD27: marker and mediator of T-cell activation? Immunol. Today 15, 307–311 (1994).

de Jong, R. et al. The CD27− subset of peripheral blood memory CD4+ lymphocytes contains functionally differentiated T lymphocytes that develop by persistent antigenic stimulation in vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 22, 993–999 (1992).

Sallusto, F. & Lanzavecchia, A. Understanding dendritic cell and T-lymphocyte traffic through the analysis of chemokine receptor expression. Immunol. Rev. 177, 134–140 (2000).

Forster, R. et al. CCR7 coordinates the primary immune response by establishing functional microenvironments in secondary lymphoid organs. Cell 99, 23–33 (1999).

He, X. S. et al. Analysis of the frequencies and of the memory T cell phenotypes of human CD8+ T cells specific for influenza A viruses. J. Infect. Dis. 187, 1075–1084 (2003).

Chen, G. et al. CD8 T cells specific for human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein–Barr virus, and cytomegalovirus lack molecules for homing to lymphoid sites of infection. Blood 98, 156–164 (2001).

Kern, F. et al. Distribution of human CMV-specific memory T cells among the CD8+ subsets defined by CD57, CD27, and CD45 isoforms. Eur. J. Immunol. 29, 2908–2915 (1999).

Sandberg, J. K., Fast, N. M. & Nixon, D. F. Functional heterogeneity of cytokines and cytolytic effector molecules in human CD8+ T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 167, 181–187 (2001).

Gamadia, L. E. et al. Differentiation of cytomegalovirus-specific CD8+ T cells in healthy and immunosuppressed virus carriers. Blood 98, 754–761 (2001).

He, X. S. et al. Quantitative analysis of hepatitis C virus-specific CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood and liver using peptide–MHC tetramers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 5692–5697 (1999).

Ogg, G. S. et al. Longitudinal phenotypic analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes: correlation with disease progression. J. Virol. 73, 9153–9160 (1999).

Tomaru, U. et al. Detection of virus-specific T cells and CD8+ T-cell epitopes by acquisition of peptide–HLA–GFP complexes: analysis of T-cell phenotype and function in chronic viral infections. Nature Med. 9, 469–476 (2003).

Nagai, M. et al. Increased activated human T cell lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I) Tax11–19-specific memory and effector CD8+ cells in patients with HTLV-I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis: correlation with HTLV-I provirus load. J. Infect. Dis. 183, 197–205 (2001).

Lechner, F. et al. CD8+ T lymphocyte responses are induced during acute hepatitis C virus infection but are not sustained. Eur. J. Immunol. 30, 2479–2487 (2000).

Croft, M. Co-stimulatory members of the TNFR family: keys to effective T cell immunity? Nature Rev. Immunol. 3, 609–620 (2003).

Lens, S. M. et al. Phenotype and function of human B cells expressing CD70 (CD27 ligand). Eur. J. Immunol. 26, 2964–2971 (1996).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr E. Eldering for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Glossary

- PERFORIN

-

A calcium-sensitive membraneolytic protein that is found in cytoplasmic granules of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells.

- GRANZYME B

-

A member of a family of serine proteinases that are mainly found in the cytoplasmic granules of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells.

- MHC CLASS I TETRAMERS

-

Fluorescent-labelled tetravalent complexes of MHC class I or class II molecules complexed with antigenic peptide. They can be used to identify antigen-specific T cells by flow cytometry.

- SEROPOSITIVITY

-

The presence of virus-specific antibodies in the serum of an individual.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Lier, R., ten Berge, I. & Gamadia, L. Human CD8+ T-cell differentiation in response to viruses. Nat Rev Immunol 3, 931–939 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/nri1254

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nri1254

This article is cited by

-

Deletion of MIF gene from live attenuated LdCen−/− parasites enhances protective CD4+ T cell immunity

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Molecular changes associated with increased TNF-α-induced apoptotis in naïve (TN) and central memory (TCM) CD8+ T cells in aged humans

Immunity & Ageing (2018)

-

The pathogenesis of microcephaly resulting from congenital infections: why is my baby’s head so small?

European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (2018)

-

A constant companion: immune recognition and response to cytomegalovirus with aging and implications for immune fitness

GeroScience (2017)

-

Cytotoxic polyfunctionality maturation of cytomegalovirus-pp65-specific CD4 + and CD8 + T-cell responses in older adults positively correlates with response size

Scientific Reports (2016)