Abstract

Endocannabinoids inhibit hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis activity; however, the neural substrates and pathways subserving this effect are not well characterized. The amygdala is a forebrain structure that provides excitatory drive to the HPA axis under conditions of stress. The aim of this study was to determine the contribution of endocannabinoid signaling within distinct amygdalar nuclei to activation of the HPA axis in response to psychological stress. Exposure of rats to 30-min restraint stress increased the hydrolytic activity of fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) and concurrently decreased content of the endocannabinoid/CB1 receptor ligand N-arachidonylethanolamine (anandamide; AEA) throughout the amygdala. In stressed rats, AEA content in the amygdala was inversely correlated with serum corticosterone concentrations. Pharmacological inhibition of FAAH activity within the basolateral amygdala complex (BLA) attenuated stress-induced corticosterone secretion; this effect was blocked by co-administration of the CB1 receptor antagonist AM251, suggesting that stress-induced decreases in CB1 receptor activation by AEA contribute to activation of the neuroendocrine stress response. Local administration into the BLA of a CB1 receptor agonist significantly reduced stress-induced corticosterone secretion, whereas administration of a CB1 receptor antagonist increased corticosterone secretion. Taken together, these findings suggest that the degree to which stressful stimuli reduce amygdalar AEA/CB1 receptor signaling contributes to the magnitude of the HPA response.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis governs the neuroendocrine adrenocortical response to aversive stimuli. Corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) neurosecretory cells within the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) integrate input from other regions of the nervous system and activation of these cells is the initiating step of the adrenocortical response to stress. The endpoint of HPA axis activation is the release of glucocorticoid hormones, such as corticosterone, from the adrenal cortex into the general circulation. Among other effects, glucocorticoids promote glucose mobilization and redirect energy stores necessary for rapid, adaptive responses to stress (Pecoraro et al, 2006). Although the HPA axis is ubiquitously activated in response to aversive stimuli, the up-stream neural circuits mediating this activation depend on the nature of the stressor. ‘Physiological’ stressors, which evoke disturbances in internal homeostasis, activate the HPA axis through a bottom–up circuit in which brainstem nuclei recruit the HPA axis directly, whereas ‘psychological’ stressors elicit a neuroendocrine response through top–down processes (Pecoraro et al, 2006; Sawchenko et al, 2000; Herman et al, 2003). In this circuit, psychological stressors activate corticothalamic sensory systems, which convey information to cortical and limbic integrative areas where information is processed and aversive salience is determined. These integrative limbic areas, particularly the amygdala, then regulate the HPA axis through trans-synaptic relays, including those within the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and local hypothalamic nuclei (Herman et al, 2005).

Recent data indicate that the endocannabinoid system negatively regulates the neuroendocrine response to psychological stress (see Gorzalka et al, 2008; Steiner and Wotjak, 2008). The endocannabinoid system is composed of two neuroactive signaling lipids, N-arachidonylethanolamine (anandamide; AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), which bind to the cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) receptor localized to axonal processes (Freund et al, 2003). Both endocannabinoid ligands and the CB1 receptor are expressed within the amygdala (Herkenham et al, 1991; Bisogno et al, 1999), and endocannabinoid signaling within the amygdala is known to modulate both excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission (Katona et al, 2001; Azad et al, 2003, 2004; Zhu and Lovinger, 2005; Domenici et al, 2006). Additionally, tissue content of AEA and 2-AG within the amygdala is modulated in response to psychological stressors (Patel et al, 2005c; Hill et al, 2008; Rademacher et al, 2008).

At a systems level, genetic or pharmacological disruption of endocannabinoid signaling increases CRH transcription within the PVN, enhances both basal and stress-induced corticosterone secretion and impairs glucocorticoid-mediated negative feedback regulation of the HPA axis (Patel et al, 2004; Cota et al, 2007; Steiner et al, 2008a). On the other hand, pharmacological augmentation of endocannabinoid neurotransmission attenuates the neuroendocrine response to psychological stressors (Patel et al, 2004). The neural circuitry subserving the inhibitory effects of endocannabinoids on the HPA axis is not well characterized; in particular, the influence of endocannabinoid signaling within limbic structures on activation of the HPA axis by psychological stress is not known. In this regard, the aim of this study was to use biochemical analyses of endocannabinoid signaling and local microinjections of cannabinoid ligands to determine the contributions of stress-induced modulation of endocannabinoid signaling within discrete nuclei of the amygdala to the activation of the HPA axis. Our findings reveal that endocannabinoid/CB1 receptor signaling in the amygdala is disrupted by acute exposure to psychological stress, which in turn contributes to stress-induced activation of the HPA axis.

METHODS

Subjects

Seventy-day-old male Sprague–Dawley rats (300 g; University of British Columbia Breeding Center) were used in this study. The rats were pair housed (except after surgical procedures, when they were individually housed) in standard maternity bins lined with contact bedding. Colony rooms were maintained at 21°C, and on a 12 h light/dark cycle, with lights on at 0900 h. All rats were given ad libitum access to Purina Rat Chow and tap water. All protocols were approved by the Canadian Council for Animal Care and the Animal Care Committee of the University of British Columbia. All studies occurred during the first third of the light cycle, during the daily nadir of HPA axis activity.

Biochemical Studies

For biochemical studies, animals were randomly assigned to either basal or stress conditions. For stress conditions, rats were put into a polystyrene tube (diameter 6 cm, length 20 cm) with breathing holes. Tubes were long enough to completely encase the rat and too narrow for turning or other large movements. Rats were left in the tubes for 30 min, then removed and immediately decapitated. Basal animals remained in their home cage until they were decapitated. The amygdala was dissected as described earlier (Hill et al, 2006), frozen in liquid nitrogen within 5 min of decapitation and stored at −80°C until analysis. Trunk blood was collected at the time of decapitation for the analysis of serum corticosterone. One cohort of animals (n=10) was used to determine brain regional endocannabinoid contents and serum corticosterone levels. Membrane fractions were isolated from brain regions of another cohort of animals (n=4) and were used for CB1 receptor radioligand binding, CB1 receptor-mediated GTPγS binding and fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) activity.

Membrane Preparation

Brain sections were homogenized in 10 volumes of TME buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 1 mM EDTA and 3 mM MgCl2). Homogenates were centrifuged at 18 000 g for 20 min and the resulting pellet, which constituted the membrane fraction, was resuspended in 10 volumes of TME buffer. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

CB1 Receptor Radioligand Binding Assay

CB1 receptor radioligand binding was performed using a Multiscreen Filtration System with Durapore 1.2-μM filters (Millipore, Bedford, MA) as described earlier (Hillard et al, 1995a). Incubations (total volume=0.2 ml) were carried out using TME buffer containing 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (TME/BSA). Membranes (10 μg protein per incubate) were added to the wells containing 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, or 2.5 nM [3H]CP 55 940, a cannabinoid CB1 receptor agonist. Ten μM Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol was used to determine nonspecific binding. Kd and Bmax values were determined by nonlinear curve fitting to the single site binding equation using GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA, USA).

CB1 Receptor-Mediated GTPγS Binding Assay

The assay for [35S]GTPγS binding was performed as described earlier by Kearn et al (1999). Membranes (final concentration, 5 μg of protein per incubation mixture) were added to TME buffer containing 0.1% fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin, 10 μmol/l GDP, and 150 mmol/l NaCl. [35S]GTPγS (final concentration, 0.65 nmol/l) was added, and the incubation was continued for 30 min at 37°C using the Multiscreen Filtration System with Durapore filters (pore size, 1.2 μm; Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μmol/l Gpp(NH)p and accounted for <15% of the total binding. Bound [35S]GTPγS was separated from free [35S]GTPγS by filtration followed by washing the filters four times with cold TME buffer containing NaCl and GDP. The cannabinoid CB1 receptor agonist WIN 55 212 was added in 1 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide at concentrations of 0, 0.1, 0.3, 0.6, 1, 2, 3, 6, 10, 20, and 30 μmol/l. In each experiment, the agonist-dependent [35S]GTPγS binding was calculated as a percentage of agonist-independent binding. The EC50 values and maximal agonist-induced increase in binding (Emax) of [35S]GTPγS were determined by fitting the data to a sigmoidal concentration–response curve using nonlinear regression (Prism; GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA).

FAAH Activity Assay

FAAH activity was measured as the conversion of AEA labeled with [3H] in the ethanolamine portion of the molecule ([3H]AEA; Omeir et al, 1995) to [3H]ethanolamine preparations as reported earlier (Hillard et al, 1995b). Membranes were incubated in a final volume of 0.5 ml of TME buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 3.0 mM MgCl2, and 1.0 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) containing 1.0 mg/ml fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin and 0.2 nM [3H]AEA. Isotherms were constructed using eight concentrations of AEA at concentrations between 10 nM and 10 μM. Incubations were carried out at 37°C and were stopped with the addition of 2 ml of chloroform/methanol (1 : 2). After standing at ambient temperature for 30 min, 0.67 ml of chloroform and 0.6 ml of water were added. Aqueous and organic phases were separated by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 10 min. The amount of [3H] in 1 ml each of the aqueous and organic phases was determined by liquid scintillation counting and the conversion of [3H]AEA to [3H]ethanolamine was calculated. The KI and Vmax values for this conversion were determined by fitting the data to a single site competition equation using Prism.

Endocannabinoid Extraction and Analysis

Brain regions were subjected to a lipid extraction process as described earlier (Patel et al, 2003). Tissue samples were weighed and placed into borosilicate glass culture tubes containing 2 ml of acetonitrile with 84 pmol of [2H8]anandamide and 186 pmol of [2H8]2-AG. Tissue was homogenized with a glass rod and sonicated for 30 min. Samples were incubated overnight at −20°C to precipitate proteins, then centrifuged at 1500 g to remove particulates. The supernatants were removed to a new glass tube and evaporated to dryness under N2 gas. The samples were resuspended in 300 μl of methanol to recapture any lipids adhering to the glass tube, and dried again under N2 gas. Final lipid extracts were suspended in 20 μl of methanol, and stored at −80oC until analysis. The contents of the two primary endocannabinoids AEA and 2-AG within lipid extracts in methanol from brain tissue were determined using isotope-dilution, liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry as described earlier (Patel et al, 2005a).

Radioimmunoassay of Serum Corticosterone

After collection, blood was allowed to settle for 1 h before centrifugation. Samples were centrifuged at 3000 g for 20 min after which serum was removed and stored at −80°C until analysis. Serum corticosterone (5 μl) was measured using commercial RIA kits (MP Biomedicals, Costa Mesa, CA), as described earlier (Bingham and Viau, 2008). Briefly, for corticosterone analysis, the serum samples were diluted 1 : 100 and 1 : 200 for basal and stress conditions, respectively, to render hormone detection within the linear part of the standard curve. [125I]-labeled corticosterone was used as trace; the corticosterone antibody cross-reacts slightly with desoxycorticosterone (0.34%) and testosterone and cortisol (0.10%).

Microinjection Studies

For microinjection studies, animals were subjected to stereotaxic surgery. Rats were anesthetized with 100 mg/kg of ketamine hydrochloride and 7 mg/kg xylazine, and implanted with bilateral 23-gauge stainless-steel guide cannulae. Separate cohorts of animals were generated with implantations of cannulae into the basolateral amygdala complex (BLA; flat skull anterior/posterior (AP)=−3.1 mm from bregma, medial/lateral (ML)=±5.0 mm from midline, dorsal/ventral (DV)=−6.1 mm from dura), the medial amygdala (MeA; AP=−2.6 mm; ML=±3.4 mm; DV=−7.4 mm) or the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA; AP=−2.2 mm; ML=±4.1 mm; DV=−6.5 mm; Paxinos and Watson (1998)). Four steel screws and dental acrylic were used to permanently affix the guide cannulae to the skull. Stainless-steel stylets (30-gauge) were inserted into the guide cannulae until the time of infusion. Immediately after surgery, antibiotic ointment was applied to the skull and surrounding incision. All rats were individually housed during recovery and were given 1 week of recovery before testing.

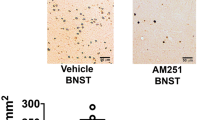

Animals received bilateral infusions of either the CB1 receptor agonist HU-210 (2.5 μg), the CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 (2.5 μg), the FAAH inhibitor URB597 (0.1 or 1.0 μg) or vehicle (DMSO). For studies determining the CB1 receptor dependency of HU-210 and URB597, mixtures of HU-210 and AM251 or URB597 and AM251 were infused using the same doses as above. These doses were chosen based on earlier data showing efficacy and selectivity for the target (McLaughlin et al, 2007; Rubino et al, 2008; Lin et al, 2006). A 30-gauge injection cannula extending 0.8 mm below the tips of the guide cannulae was used for infusions. Drug solutions or vehicle were delivered at a rate of 0.5 μl/72 s using a microsyringe pump (Sage Instruments Model 341). Injection cannulae were left in place for an additional 1 min to allow for diffusion. After infusions, animals were returned to their home cages. For stress induction, animals in studies using HU-210 or AM251 were left in their cages for 10 min before being put into restrainers, whereas animals for studies using URB597 were left in their cages for 20 min (to allow time for enzyme inhibition to occur) before being put into restrainers. At the conclusion of the 30-min restraint stress session, a small nick was made at the tip of the tail from which 300 μl of blood was collected for corticosterone analysis. Blood from a tail nick was also collected from the nonstressed rats at 40 or 50 min after bilateral infusions, depending on the drug infused. All rats were killed in a carbon dioxide chamber 24 h after testing. Brains were removed and fixed in a 4% formalin solution. The brains were frozen and sliced in 50 μm sections and mounted. Placements were verified with reference to the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1998) and histological analysis showed that approximately 85% of cannula placements were in boundaries of the nuclei of interest (see Figure 1). Subjects with cannulae outside of the desired structure were excluded from subsequent analysis.

Schematic of coronal sections of the rat brain showing the placements of the tips of the cannulae for all rats that received infusions of HU-210, AM251 or URB597 into the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala, the central nucleus of the amygdala and the medial amygdala. Representative histological pictures of infusions into the amygdala nuclei are adjacent to placement diagrams.

Statistics

Analyses of the effects of restraint stress on the tissue contents of AEA and 2-AG, CB1 receptor binding parameters and CB1 receptor-mediated GTPγS binding were performed using independent t-tests. Examination of the effects of URB597 on stress-induced corticosterone secretion was performed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), whereas the effects of HU-210 and AM251 on basal and stress-induced corticosterone secretion were analyzed using a univariate ANOVA with drug (HU-210 or AM251) and stress as fixed factors. For all neuroendocrine studies, post hoc analysis was performed using a Tukey's test. All analyses used P<0.05 as an indication of significance.

RESULTS

Psychological Stress Dampens Endocannabinoid Signaling Within the Amygdala

Restraint stress resulted in a significant reduction in tissue content of AEA within the amygdala [t(18)=2.35, P<0.03; Figure 2], whereas there was no effect of stress on amygdalar 2-AG content [t(18)=0.85, P>0.05; Figure 2]. The reduction in amygdalar AEA content after stress is likely attributable to an enhancement of hydrolysis as stress robustly increased the Vmax of FAAH for AEA hydrolysis [t(6)=2.59, P<0.05; Table 1 ]. Stress did not affect the Km of FAAH for AEA [t(6)=1.58, P>0.05; Table 1].

Acute psychological stress modulates endocannabinoid content in the amygdala. The effect of 30-min restraint stress on the tissue content of the endocannabinoid ligands N-arachidonylethanolamide (anandamide; AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) within the amygdala. Values are denoted as means±SEM. *Significant differences (P<0.05) between animals under basal and stress conditions.

Exposure of rodents to 30 min of restraint stress did not significantly affect the maximal binding site density [Bmax; t(6)=1.10, P>0.05; Table 2 ] or the binding affinity of [3H]CP55940 for the CB1 receptor [Kd; t(6)=1.27, P>0.05; Table 2]. Similarly, there was no effect of restraint stress on the maximal stimulation of CB1 receptor-mediated GTPγS binding [t(6)=0.53, P>0.05; Table 2], but there was a trend for stress to increase the EC50 of WIN 55212-2, suggestive of reduced agonist sensitivity of the CB1 receptor to induce GTP exchange [t(6)=1.94, P=0.10; Table 2].

Suppression of AEA/CB1 Receptor Signaling Within the BLA Contributes to Stress-Induced Activation of the HPA Axis

As anticipated, restraint stress increased serum corticosterone levels [t(18)=20.7, P<0.001; Figure 3]. To determine whether the changes in amygdalar endocannabinoid content after stress were related to the magnitude of the HPA axis response, we examined the correlation between serum corticosterone concentrations and both AEA and 2-AG, under stress conditions. Although amygdalar 2-AG tissue content did not exhibit a significant correlation with serum corticosterone (r=−0.18, P>0.05; Figure 3), amygdalar AEA content was significantly and negatively correlated with corticosterone levels (r=−0.72, P<0.02; Figure 3), indicating that higher levels of serum corticosterone after stress were associated with lower levels of AEA content within the amygdala.

Acute stress-induced increases in corticosterone secretion: correlations with endocannabinoid content within the amygdala. The 30-min restraint stress resulted in a significant increase in circulating corticosterone. Values are denoted as means±SEM. *Significant differences (P<0.05) in corticosterone levels between basal and stress conditions. Under stress conditions, the magnitude of corticosterone secretion correlated significantly and negatively with anandamide (AEA) content in the amygdala. There was no significant correlation between corticosterone and 2-AG content in the amygdala. *Significant correlation (P<0.05).

To further explore the relationship between amygdalar FAAH activity, AEA content and serum corticosterone, we determined the effect of local inhibition of FAAH activity within the BLA, CeA, and MeA on stress-induced corticosterone secretion. Administration of the FAAH inhibitor URB597 blocks AEA hydrolysis by FAAH and increases AEA content (Kathuria et al, 2003), providing an ideal tool to examine this relationship. Within the BLA there was a significant effect of infusion of the FAAH inhibitor, URB597, on stress-induced corticosterone secretion [F(4,26)=65.7, P<0.001; Figure 4], with post hoc analysis revealing that administration of 0.1 μg URB597 into the BLA significantly reduced stress-induced increases in corticosterone secretion (P<0.05). The fact that 1 μg of URB597 into the BLA did not mimic the effects seen with the lower dose is consistent with earlier work showing that URB597 is optimally effective at a dose of 0.1 μg, presumably due to the fact that greater increases in AEA are believed to lose selectivity for the CB1 receptor and begin to saturate TRPV1 vanilloid receptors (Rubino et al, 2008). Animals that received an infusion of the CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 in conjunction with URB597 exhibited no significant difference in stress-induced corticosterone secretion relative to vehicle-infused animals (P>0.05), supporting the hypothesis that URB597 administration into the BLA, at this dose, reduced HPA axis activation through increased activation of the CB1 receptor by AEA. URB597 infusions into the CeA and MeA were without effect on stress-induced serum corticosterone levels (Table 3).

Inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase within the basolateral amygdala reduces stress-induced corticosterone secretion. Infusion of URB597 (0.1 and 1 μg), a pharmacological inhibitor of FAAH, into the basolateral amygdala significantly reduced stress-induced increases in corticosterone secretion. Values are denoted as means±SEM. *Significant differences (P<0.05).

These data suggest that decreased tonic CB1 receptor activity within the BLA promotes HPA axis activation by stress; to test this hypothesis, we examined the effects of local administration of AM251 into the BLA on both basal and stress-induced corticosterone secretion (Figure 5). There was a significant main effect of both stress [F(1,15)=121.77, P<0.001] and intra-BLA administration of AM251 [F(1,15)=4.81, P<0.05] on serum corticosterone but no significant interaction between AM251 administration and stress [F(1,15)=0.14, P>0.05]. AM251 administration into the BLA resulted in a moderate increase in serum corticosterone under both basal and stress conditions, but did not potentiate stress-induced corticosterone secretion, per se. Infusion of AM251 into the CeA and MeA did not affect stress-induced serum corticosterone (Figure 5).

Antagonism of the CB1 receptor within distinct amygdalar nuclei differentially affects stress-induced increases in corticosterone secretion. Infusion of the CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 (2.5 μg) into the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala (BLA) significantly increased corticosterone secretion, whereas there was no effect of AM251 infusion into the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) or the medial amygdala (MeA). Values are denoted as means±SEM. *Significant differences (P<0.05).

In the next set of studies, we examined the effects of intra-amygdalar infusion of a direct CB1 receptor agonist on basal and stress-induced serum corticosterone. There was a significant interaction between administration of the CB1 receptor agonist HU-210 into the BLA and stress on serum corticosterone [F(1,15)=12.72, P<0.005; Figure 6]. Post hoc analysis revealed that HU-210 administration into the BLA had no effect on serum corticosterone levels in nonstressed rats; however, administration of HU-210 into the BLA before stress resulted in a significant reduction of stress-induced corticosterone secretion compared with vehicle (P<0.01). When HU-210 was co-administered with the CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 into the BLA (Figure 6), corticosterone levels after stress were no different than those of animals receiving a vehicle infusion before stress (P>0.05) and were significantly higher than those after HU-210 infusion alone (P<0.05).

Pharmacological activation of the CB1 receptor within distinct amygdalar nuclei differentially affects stress-induced increases in corticosterone secretion. Infusion of the CB1 receptor agonist HU-210 (HU; 2.5 μg) into the basolateral amygdala (BLA) suppressed stress-induced corticosterone secretion, in a CB1 receptor-dependent manner, whereas infusion of HU-210 into the medial amygdala (MeA) enhanced stress-induced corticosterone secretion. There was no effect of HU-210 infusion into the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA). Values are denoted as means±SEM. *Significant differences (P<0.05).

There was a significant interaction between stress and administration of HU-210 into the MeA on serum corticosterone levels [F(1,15)=6.72, P<0.03; Figure 6] with subsequent analysis indicating that administration of HU-210 into the MeA before stress resulted in a significant facilitation of stress-induced corticosterone secretion (P<0.02 relative to vehicle-infused animals). There was no significant interaction between stress and infusion of HU-210 into the CeA [F(1,13)=0.3, P>0.05; Figure 6] nor a main effect of HU-210 administration into the CeA [F(1,13)=0.2, P>0.05] on serum corticosterone levels, whereas there was a main effect of stress to increase serum corticosterone [F(1,13)=52.7, P<0.001].

DISCUSSION

The results of this study show that exposure of rats to a psychological stressor evokes an increase in FAAH-mediated hydrolysis of AEA within the amygdala, which results in a suppression of AEA/CB1 receptor signaling within the BLA. This reduction in AEA/CB1 receptor signaling within the BLA determines the magnitude of the corticosterone response during the stress-induced activation of the HPA axis. On the basis of these and other findings, we propose that AEA/CB1 receptor signaling in the rat amygdala is tonically active, and that it serves as a functional gatekeeper of HPA axis activation. Thus, after exposure to stress, FAAH activity increases, which results in a drop in AEA tone that promotes neuronal activation within the BLA and increases activation of the HPA axis.

Stress-Induced Suppression of AEA/CB1 Signaling Within the BLA Promotes Activation of the HPA Axis

The effect of restraint stress to reduce the tissue content of AEA within the amygdala of the rat is consistent with earlier reports in mice (Patel et al, 2005c; Rademacher et al, 2008). Within this study, the content of AEA within the amygdala determined at the termination of restraint stress was negatively correlated with the magnitude of the corticosterone response to stress within these same animals, indicating a relationship between amygdalar AEA and HPA axis activation by a psychological stressor. As pharmacological inhibition of FAAH activity within the BLA reduced the corticosterone response to psychological stress, it is likely that AEA content in the BLA has a function in constraining HPA axis activation, rather than the converse explanation, that the stress-induced reduction in amygdalar AEA is driven by increased levels of glucocorticoids. It is our hypothesis that stress-induced activation of FAAH within the amygdala is an early event in the cascade of signaling processes that ultimately regulate glucocorticoid secretion. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that we have seen reductions in AEA as rapidly as 5 min after the initiation of stress, which would preclude mediation by an increase in glucocorticoid secretion (MN Hill, RJ McLaughlin, BB Gorzalka and CJ Hillard, unpublished findings). Furthermore, despite the fact that tissue measurements of FAAH activity and AEA content were performed in sections of the entire amygdala, the pharmacological data would suggest that this increase in FAAH activity and reduction in AEA content is primarily occurring in the BLA. However, the mechanism by which stress rapidly induces FAAH activity has yet to be determined.

Consistent with this hypothesis, antagonism of the CB1 receptor within the BLA increased HPA axis drive, whereas there was no effect of CB1 receptor antagonism within the CeA or MeA on HPA axis output. Collectively, these data suggest that AEA/CB1 receptor signaling in the BLA exerts tonic inhibition over the HPA axis. However, given that the independent effects of FAAH inhibition and CB1 receptor antagonism within the BLA on stress-induced corticosterone secretion were modest, it appears that the role of endocannabinoid signaling within the BLA is modulatory in nature.

Pharmacological Activation of CB1 Receptors Within the BLA Dampens HPA Axis Activation in Response to Stress

In agreement with the model that CB1 receptor activation within the BLA limits activation of the HPA axis, local administration of the CB1 receptor agonist HU-210 into the BLA reduced the stress-induced increase in circulating levels of corticosterone. This phenomenon was mediated through a CB1 receptor-dependent process (as it was prevented by co-administration of the CB1 receptor antagonist AM251), and the magnitude of this suppression was greater than what was seen after inhibition of AEA hydrolysis. In contrast, infusion of HU-210 into the CeA did not modulate the HPA axis response to restraint stress, whereas administration of HU-210 into the MeA resulted in an unexpected facilitation of stress-induced corticosterone secretion. These data show that the role of CB1 receptor signaling in HPA axis regulation is functionally dissociable among amygdalar nuclei. Given that expression analysis of the CB1 receptor reveals considerably higher densities in the BLA than in the CeA or MeA (Herkenham et al, 1991; Katona et al, 2001), it is not surprising that the most robust effects that were documented occurred through modulation of CB1 receptor signaling in the BLA. Additionally, the fact that administration of a CB1 receptor agonist into distinct amygdalar nuclei exerted different responses on stress-induced corticosterone secretion, confirms that the effects are due to CB1 receptor activation within these restricted regions and not due to spillover of the infusion into surrounding amygdalar regions.

The mechanism by which CB1 receptor activity within the BLA regulates HPA axis activity is not known. With respect to amygdalar nuclei, the predominance of research has focused on the roles of the CeA and MeA in the neuroendocrine response to stress, whereas the BLA has been largely neglected (Herman et al, 2003, 2005; Dayas et al, 1999). The BLA is the integration site within the amygdala that receives afferents from cortical, hippocampal and thalamic sites encoding external sensory and visceral information (McDonald, 1992; Sah et al, 2003). Immediate early gene studies have revealed that projection neurons of the BLA are activated in response to restraint stress (Patel et al, 2005b; Reznikov et al, 2008) and lesions of the BLA dampen neuroendocrine responses to psychological stressors, such as restraint or footshock (Bhatnagar et al, 2004; Goldstein et al, 1996). Similarly, direct stimulation of the BLA can increase HPA axis activity (Szafarcyk et al, 1986; Feldman et al, 1982, 1983). Moreover, overexpression of the SK2 potassium channel in the BLA attenuates stress-induced corticosterone secretion (Mitra et al, 2009). These data suggest that activation of BLA projection neurons positively contribute to HPA axis activation during psychological stress, likely through projection relays to the MeA or BNST, which, in turn, communicate directly to the PVN (Herman et al, 2003, 2005; Ulrich-Lai and Herman, 2009).

There is convincing evidence that the CB1 receptor is present on both GABAergic and glutamatergic axons in the BLA. Immunohistochemical studies showed that CB1 receptors are present on GABAergic synapses and function to inhibit GABAergic transmission (Katona et al, 2001; McDonald and Mascagni, 2001). Although it has been difficult to show the presence of CB1 receptors on glutamatergic terminals using immunohistochemistry (Katona et al, 2001; McDonald and Mascagni, 2001), electrophysiological studies have established that activation of CB1 receptors within the BLA inhibits excitatory synaptic transmission and the firing rate of BLA projection neurons (Pistis et al, 2004; Perra et al, 2008; Domenici et al, 2006; Azad et al, 2003). Furthermore, the ability of cannabinoids to reduce glutamatergic signaling overrides the suppression of GABAergic transmission, resulting in a net reduction in the excitability of BLA projection neurons (Azad et al, 2003). In line with this, immediate early-gene studies have found that systemic administration of a CB1 receptor antagonist increases the neuronal activation of the BLA in unstressed animals (Singh et al, 2004; Patel et al, 2005b), supporting the hypothesis that endocannabinoid signaling tonically inhibits excitatory transmission in the BLA. Given that the primary source of excitatory inputs to BLA projection neurons are cortical and thalamic afferents transmitting sensory information regarding external conditions (Sah et al, 2003: McDonald, 1992), CB1 receptor activation within the BLA likely attenuates HPA axis activity by gating excitatory sensory input afferents to the BLA, and subsequently dampens the firing rate of BLA projection neurons, which exert trans-synaptic relays to the PVN. This hypothesis is in agreement with recent transgenic data showing that endocannabinoid regulation of HPA axis responsivity is governed by CB1 receptors on principal forebrain neurons, but not GABAergic interneurons (Steiner et al, 2008b).

It is also possible that the effects of endocannabinoid signaling in the BLA on the HPA axis are not due to modulation of the CRH-ACTH pathway originating in the PVN, but instead are due to action on the autonomic arm of the stress axis. Specifically, it is possible that changes in amygdalar neuronal activity could affect principal autonomic relay nuclei, such as those in the brainstem and regions of the PVN that exhibit projections to autonomic spinal regions, which in turn could affect corticosterone secretion at a different peripheral level, either through changes in adrenal cortical cell sensitivity to ACTH or in hepatic blood flow to inhibit corticosterone clearance from the circulation. Although this pathway could account for the modest effect size that is seen after modulation of endocannabinoid signaling in the BLA, it seems less plausible given that the BLA, as well as the MeA, through which the BLA is believed to communicate under conditions of psychological stress (Herman et al, 2005; Ulrich-Lai and Herman, 2009), exhibit little to no projections to the primary autonomic output nuclei (Ulrich-Lai and Herman, 2009).

It should be noted, however, that we have found earlier using c-fos immunohistochemistry, that CB1 receptor agonists (but not FAAH inhibitors) potentiate stress-induced neuronal activation of the CeA, but not the BLA, when administered systemically to mice (Patel et al, 2005b). It is our hypothesis that systemically administered agonists, which globally increase CB1 receptor signaling throughout the brain, promote activation of incoming excitatory afferents to the amygdala through effects in an extra-amygdalar brain region. This pattern of activation could override the local suppressive effect AEA/CB1 receptor activation within the BLA and concurrently promote activation of the CeA.

Activation of CB1 Receptors Within the Medial or Central Nucleus of the Amygdala Exerts Differential Effects on Stress-Induced HPA Axis Activation

Administration of the CB1 receptor agonist HU-210 into the MeA before restraint potentiated the corticosterone response to stress. Similarly, systemic administration of CB1 receptor agonists can enhance stress-induced HPA axis activation (Patel et al, 2004; Jacobs et al, 1979; Hill and Gorzalka, 2006). The present data suggest that activation of CB1 receptors within the MeA could contribute to the stress-potentiating effects of systemically administered cannabinoid agonists. Given that lesion studies have indicated that the MeA is recruited by psychological stressors to activate the HPA axis (Dayas et al, 1999; Figueiredo et al, 2003; Ma and Morilak, 2005; Herman et al, 2005), the current data suggest that CB1 receptor activation within the MeA, when coupled with stressful stimuli, promotes the output neurons of this nucleus to increase the neuronal activation of the PVN. Our finding that neither AM251 nor URB597 infusions in the MeA affected the corticosterone response to stress suggests that this CB1 receptor-mediated effect is not endogenously activated by stress.

Pharmacological modulation of CB1 receptor signaling within the CeA did not alter the HPA axis response to acute restraint stress. This finding is not entirely unexpected, as the expression levels of FAAH and the CB1 receptor within this part of the amygdala are relatively sparse (Katona et al, 2001; Gulyas et al, 2004). Furthermore, the CeA appears to be more important for HPA axis activation after physiological stressors, rather than psychological stressors, particularly restraint (Prewitt and Herman, 1997; Dayas et al, 1999, 2001).

Neurobehavioral Implications

The present findings likely generalize and extend beyond the regulation of the HPA axis. Amygdalar endocannabinoid signaling is important for adaptive emotional flexibility (Marsicano et al, 2002; Lin et al, 2006), such as fear extinction, which is disrupted by stressful stimuli (Izquierdo et al, 2006; Miracle et al, 2006; Holmes and Wellman, 2009; Baran et al, 2009). Specifically, AEA signaling within the amygdala mediates forms of synaptic plasticity, such as inhibitory long-term depression, which are conducive to fear extinction and emotional flexibility (Azad et al, 2004). Accordingly, it is possible that stress-induced reductions in AEA/CB1 receptor signaling in the BLA contribute to the alterations in emotional reactivity and flexibility elicited by exposure to stressful stimuli.

A recent report has shown that endocannabinoid signaling within the BLA is also critical for the consolidation of aversive memories (Campolongo et al, 2009). Moreover, this research showed that endocannabinoid signaling in the BLA was also required in order for corticosterone to modulate aversive memory consolidation (Campolongo et al, 2009), suggesting that glucocorticoids were capable of inducing amygdalar endocannabinoid synthesis in vivo (Hill and McEwen, 2009). As the current data indicate that stress decreases amygdalar AEA content, collectively, these studies would suggest that stress and glucocorticoids differentially affect amygdalar endocannabinoid content, per se. That is, stress may decrease amygdalar endocannabinoid tone, through a glucocorticoid-independent mechanism of action, whereas glucocorticoids in the absence of stress may promote amygdalar endocannabinoid signaling. In a similar vein, unlike stress exposure, administration of glucocorticoid hormones can actually promote emotional flexibility and enhance fear extinction (de Quervain et al, 2009; Yang et al, 2006). Given the parallels between the effects of stress and glucocorticoids on fear extinction and amygdalar endocannabinoid signaling, the distinct possibility exists that endocannabinoid signaling is a direct mediator of these processes on adaptive emotional flexibility. Future research is required to address this question.

Conclusions

Psychological stress is hypothesized to activate the HPA axis through a top–down process wherein the HPA axis is activated by a complex network of afferents arising from the limbic forebrain (Pecoraro et al, 2006; Herman et al, 2003; Sawchenko et al, 2000). Within this circuit, the amygdala has been identified as a primary site providing excitatory drive to the HPA axis (Herman et al, 2005). The present findings suggest that endocannabinoid signaling is integrated into this circuit such that stress dampens AEA/CB1 receptor signaling within the BLA, which in turn modulates the magnitude of HPA axis responses to stressful stimuli. This process, and ability of CB1 receptors to inhibit glutamate release from excitatory afferents, suggests a model by which tonic AEA within the BLA produces steady-state activation of the CB1 receptor and results in tonic inhibition of corticothalamic sensory afferents to the BLA. The application of a psychological stressor results in increased FAAH activity, which reduces AEA/CB1 receptor signaling, and disinhibits excitatory transmission in the BLA. As a result, the neural activity of BLA projection neurons that indirectly communicate with the PVN is increased. These data support the ‘gatekeeper’ hypothesis of endocannabinoid regulation of the HPA axis (Patel et al, 2004), but show that in addition to the PVN (Di et al, 2003), the BLA is an important structure involved in the suppression of the neuroendocrine response to stress by endocannabinoid signaling. Taken together, the present data indicate that stress-induced regulation of endocannabinoid signaling within the amygdala could be an important determinant in the neuroendocrine, and possibly emotional, responses to aversive, environmental stimuli.

References

Azad SC, Eder M, Marsicano G, Lutz B, Zieglgansberger W, Rammes G (2003). Activation of the cannabinoid receptor type 1 decreases glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptic transmission in the lateral amygdala of the mouse. Learn Mem 10: 116–128.

Azad SC, Monory K, Marsicano G, Cravatt BF, Lutz B, Zieglgansberger W et al (2004). Circuitry for associative plasticity in the amygdala involves endocannabinoid signaling. J Neurosci 24: 9953–9961.

Baran SE, Armstrong CE, Niren DC, Hanna JJ, Conrad CD (2009). Chronic stress and sex differences on the recall of fear conditioning and extinction. Neurobiol Learn Mem 91: 323–332.

Bhatnagar S, Vining C, Denski K (2004). Regulation of chronic stress-induced changes in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity by the basolateral amygdala. Ann NY Acad Sci 1032: 315–319.

Bingham B, Viau V (2008). Neonatal gonadectomy and adult testosterone replacement suggest an involvement of limbic arginine vasopressin and androgen receptors in the organization of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Endocrinology 149: 3581–3591.

Bisogno T, Berrendero F, Ambrosino G, Cebeira M, Ramos JA, Fernandez-Ruiz JJ et al (1999). Brain regional distribution of endocannabinoids: implications for their biosynthesis and biological function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 256: 377–380.

Campolongo P, Roozendaal B, Trezza V, Hauer D, Schelling G, McGaugh JL et al (2009). Endocannabinoids in the rat basolaterl amaygdala enhance memory consolidation and enable glucocorticoid modulation of memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 4888–4893.

Cota D, Steiner MA, Marsicano G, Cervino C, Herman JP, Grubler Y et al (2007). Requirement of cannabinoid receptor type 1 for the basal modulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function. Endocrinology 148: 1574–1581.

Dayas CV, Buller KM, Day TA (1999). Neuroendocrine responses to an emotional stressor: evidence for involvement of the medial but not the central amygdala. Eur J Neurosci 11: 2312–2322.

Dayas CV, Buller KM, Crane JW, Xu Y, Day TA (2001). Stressor categorization: acute physical and psychological stressors elicit distinctive recruitment patterns in the amygdala and in medullary noradrenergic cell groups. Eur J Neurosci 14: 1143–1152.

de Quervain DJ, Aerni A, Schelling G, Roozendaal B (2009). Glucocorticoids and the regulation of memory in health and disease. Front Neuroendocrinol 30: 358–370.

Di S, Malcher-Lopes R, Halmos KC, Tasker JG (2003). Nongenomic glucocorticoid inhibition via endocannabinoid release in the hypothalamus: a fast feedback mechanism. J Neurosci 23: 4850–4857.

Domenici MR, Azad SC, Marsicano G, Schierloh C, Wotjak CT, Dodt HU et al (2006). Cannabinoid receptor type 1 located on presynaptic terminals of principal neurons in the forebrain controls glutamatergic synaptic transmission. J Neurosci 26: 5794–5799.

Feldman S, Conforti N, Siegel RA (1982). Adrenocortical responses following limbic stimulation in rats with hypothalamic deafferentations. Neuroendocrinology 35: 205–211.

Feldman S, Siegel RA, Conforti N (1983). Differential effects of medial forebrain bundle lesions on adrenocortical responses following limbic stimulation. Neuroscience 9: 157–163.

Figueiredo HF, Bruestle A, Bodie B, Dolgas CM, Herman JP (2003). The medial prefrontal cortex differentially regulates stress-induced c-fos expression in the forebrain depending on type of stressor. Eur J Neurosci 18: 2357–2364.

Freund TF, Katona I, Piomelli D (2003). Role of endogenous cannabinoids in synaptic signaling. Physiol Rev 83: 1017–1066.

Goldstein LE, Rasmusson AM, Bunney BS, Roth RH (1996). Role of the amygdala in the coordination of behavioral, neuroendocrine, and prefrontal cortical monoamine responses to psychological stress in the rat. J Neurosci 16: 4787–4798.

Gorzalka BB, Hill MN, Hillard CJ (2008). Regulation of endocannabinoid signaling by stress: implications for stress-related affective disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 32: 1152–1160.

Gulyas AI, Cravatt BF, Bracey MH, Dinh TP, Piomelli D, Boscia F et al (2004). Segregation of two endocannabinoid-hydrolyzing enzymes into pre- and postsynaptic compartments in the rat hippocampus, cerebellum and amygdala. Eur J Neurosci 20: 441–458.

Herkenham M, Lynn AB, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, de Costa BR, Rice KC (1991). Characterization and localization of cannabinoid receptors in rat brain: a quantitative in vitro autoradiographic study. J Neurosci 11: 563–583.

Herman JP, Figueiredo HF, Mueller NK, Ulrich-Lai Y, Ostrander MM, Choi DC et al (2003). Central mechanisms of stress integration: hierarchical circuitry controlling hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical responsiveness. Front Neuroendocrinol 24: 151–180.

Herman JP, Ostrander MM, Mueller NK, Figueiredo HF (2005). Limbic system mechanisms of stress regulation: hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 29: 1201–1213.

Hill MN, Carrier EJ, McLaughlin RJ, Morrish AC, Meier SE, Hillard CJ et al (2008). Regional alterations in the endocannabinoid system in an animal model of depression: effects of concurrent antidepressant treatment. J Neurochem 106: 2322–2336.

Hill MN, Gorzalka BB (2006). Increased sensitivity to restraint stress and novelty-induced emotionality following long-term, high dose cannabinoid exposure. Psychoneuroendocrinology 31: 526–536.

Hill MN, McEwen BS (2009). Endocannabinoids: the silent partner of glucocorticoids in the synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 4579–4580.

Hill MN, Ho WS, Sinopoli KJ, Viau V, Hillard CJ, Gorzalka BB (2006). Involvement of the endocannabinoid system in the ability of long-term tricyclic antidepressant treatment to suppress stress-induced activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Neuropsychopharmacology 31: 2591–2599.

Hillard CJ, Edgemond WS, Campbell WB (1995a). Characterization of ligand binding to the cannabinoid receptor of rat brain membranes using a novel method: application to anandamide. J Neurochem 64: 677–683.

Hillard CJ, Wilkison DM, Edgemond WS, Campbell WB (1995b). Characterization of the kinetics and distribution of N-arachidonylethanolamine (anandamide) hydrolysis by rat brain. Biochim Biophys Acta 1257: 249–256.

Holmes A, Wellman CL (2009). Stress-induced prefrontal reorganization and executive dysfunction in rodents. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 33: 773–783.

Izquierdo A, Wellman CL, Holmes A (2006). Brief uncontrollable stress causes dendritic retraction in infralimbic cortex and resistance to fear extinction in mice. J Neurosci 26: 5733–5738.

Jacobs JA, Dellarco AJ, Manfredi RA, Harclerode J (1979). The effects of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol, and shock on plasma corticosterone concentrations in rats. J Pharm Pharmacol 31: 341–342.

Kathuria S, Gaetani S, Fegley D, Valino S, Duranti A, Tontini A et al (2003). Modulation of anxiety through blockade of anandamide hydrolysis. Nat Med 9: 76–81.

Katona I, Rancz EA, Acsady L, Ledent C, Mackie K, Hajos N et al (2001). Distribution of CB1 cannabinoid receptors in the amygdala and their role in the control of GABAergic transmission. J Neurosci 21: 9506–9518.

Kearn CS, Greenberg MJ, DiCamelli R, Kurzawa K, Hillard CJ (1999). Relationships between ligand affinities for the cerebellar cannabinoid receptor CB1 and the induction of GDP/GTP exchange. J Neurochem 72: 2379–2387.

Lin HC, Mao SC, Gean PW (2006). Effects of intra-amygdala infusion of CB1 receptor agonists on the reconsolidation of fear-potentiated startle. Learn Mem 13: 316–321.

McDonald AJ (1992). Projection neurons of the basolateral amygdala: a correlative Golgi and retrograde tract tracing study. Brain Res Bull 28: 179–185.

McDonald AJ, Mascagni F (2001). Localization of the CB1 type cannabinoid receptor in the rat basolateral amygdala: high concentrations in a subpopulation of cholecystokinin-containing interneurons. Neuroscience 107: 641–652.

McLaughlin RJ, Hill MN, Morrish AC, Gorzalka BB (2007). Local enhancement of cannabinoid CB1 receptor signalling in the dorsal hippocampus elicits an antidepressant-like effect. Behav Pharmacol 18: 431–438.

Ma S, Morilak DA (2005). Norepinephrine release in medial amygdala facilitates activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in response to acute immobilisation stress. J Neuroendocrinol 17: 22–28.

Marsicano G, Wotjak CT, Azad SC, Bisogno T, Rammes G, Cascio MG et al (2002). The endogenous cannabinoid system controls extinction of aversive memories. Nature 418: 530–534.

Miracle AD, Brace MF, Huyck KD, Singler SA, Wellman CL (2006). Chronic stress impairs recall of extinction of conditioned fear. Neurobiol Learn Mem 85: 213–218.

Mitra R, Ferguson D, Sapolsky RM (2009). SK2 potassium channel overexpression in basolateral amygdala reduces anxiety, stress-induced corticosterone secretion and dendritic arborization. Mol Psychiatry (in press).

Omeir RL, Chin S, Hong Y, Ahern DG, Deutsch DG (1995). Arachidonoyl ethanolamide-[1,2-14C] as a substrate for anandamide amidase. Life Sci 56: 1999–2005.

Patel S, Rademacher DJ, Hillard CJ (2003). Differential regulation of the endocannabinoids anandamide and 2-arachidonylglycerol within the limbic forebrain by dopamine receptor activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 306: 880–888.

Patel S, Roelke CT, Rademacher DJ, Cullinan WE, Hillard CJ (2004). Endocannabinoid signaling negatively modulates stress-induced activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Endocrinology 145: 5431–5438.

Patel S, Carrier EJ, Ho WS, Rademacher DJ, Cunningham S, Reddy DS et al (2005a). The postmortal accumulation of brain N-arachidonylethanolamine (anandamide) is dependent upon fatty acid amide hydrolase activity. J Lipid Res 46: 342–349.

Patel S, Cravatt BF, Hillard CJ (2005b). Synergistic interactions between cannabinoids and environmental stress in the activation of the central amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology 30: 497–507.

Patel S, Roelke CT, Rademacher DJ, Hillard CJ (2005c). Inhibition of restraint stress-induced neural and behavioural activation by endogenous cannabinoid signalling. Eur J Neurosci 21: 1057–1069.

Paxinos G, Watson C (1998). The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 4th edn. Academic: San Diego.

Pecoraro N, Dallman MF, Warne JP, Ginsberg AB, Laugero KD, la Fleur SE et al (2006). From Malthus to motive: how the HPA axis engineers the phenotype, yoking needs to wants. Prog Neurobiol 79: 247–340.

Perra S, Pillolla G, Luchicchi A, Pistis M (2008). Alcohol inhibits spontaneous activity of basolateral amygdala projection neurons in the rat: involvement of the endocannabinoid system. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32: 443–449.

Pistis M, Perra S, Pillolla G, Melis M, Gessa GL, Muntoni AL (2004). Cannabinoids modulate neuronal firing in the rat basolateral amygdala: evidence for CB1- and non-CB1-mediated actions. Neuropharmacology 46: 115–125.

Prewitt CM, Herman JP (1997). Hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical regulation following lesions of the central nucleus of the amygdala. Stress 1: 263–280.

Rademacher DJ, Meier SE, Shi L, Ho WS, Jarrahian A, Hillard CJ (2008). Effects of acute and repeated restraint stress on endocannabinoid content in the amygdala, ventral striatum, and medial prefrontal cortex in mice. Neuropharmacology 54: 108–116.

Reznikov LR, Reagan LP, Fadel JR (2008). Activation of phenotypically distinct neuronal subpopulations in the anterior subdivision of the rat basolateral amygdala following acute and repeated stress. J Comp Neurol 508: 458–472.

Rubino T, Realini N, Castiglioni C, Guidali C, Vigano D, Marras E et al (2008). Role in anxiety behavior of the endocannabinoid system in the prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex 18: 1292–1301.

Sah P, Faber ES, Lopez de Armentia M, Power J (2003). The amygdaloid complex: anatomy and physiology. Physiol Rev 83: 803–834.

Sawchenko PE, Li HY, Ericsson A (2000). Circuits and mechanisms governing hypothalamic responses to stress: a tale of two paradigms. Prog Brain Res 122: 61–78.

Singh ME, Verty AN, Price I, McGregor IS, Mallet PE (2004). Modulation of morphine-induced Fos-immunoreactivity by the cannabinoid receptor antagonist SR 141716. Neuropharmacology 47: 1157–1169.

Steiner MA, Marsicano G, Nestler EJ, Holsboer F, Lutz B, Wotjak CT (2008a). Antidepressant-like behavioral effects of impaired cannabinoid receptor type 1 signaling coincide with exaggerated corticosterone secretion in mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology 33: 54–67.

Steiner MA, Marsicano G, Wotjak CT, Lutz B (2008b). Conditional cannabinoid receptor type 1 mutants reveal neuron subpopulation-specific effects on behavioral and neuroendocrine stress responses. Psychoneuroendocrinology 33: 1165–1170.

Steiner MA, Wotjak CT (2008). Role of the endocannabinoid system in regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Prog Brain Res 170: 397–432.

Szafarcyk A, Caracchini M, Rondouin G, Ixart G, Malaval F, Assenmacher I (1986). Plasma ACTH and corticosterone responses to limbic kindling in the rat. Exp Neurol 92: 583–590.

Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP (2009). Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nat Rev Neurosci 10: 397–409.

Yang YL, Chao PK, Lu KT (2006). Systemic and intra-amygdala administration of glucocorticoid agonist and antagonist modulate extinction of conditioned fear. Neuropsychopharmacology 31: 912–924.

Zhu PJ, Lovinger DM (2005). Retrograde endocannabinoid signaling in a postsynaptic neuron/synaptic bouton preparation from basolateral amygdala. J Neurosci 25: 6199–6207.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by operating grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) to BBG and by National Institute of Health (NIH) grant R21DA022439 to CJH; partial funding was provided by Research for a Healthier Tomorrow, a component of the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin endowment at the Medical College of Wisconsin (CJH); by an NSERC postgraduate scholarship and a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR) Trainee Award to MNH; SBF and VV are MSFHR senior scholars.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hill, M., McLaughlin, R., Morrish, A. et al. Suppression of Amygdalar Endocannabinoid Signaling by Stress Contributes to Activation of the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis. Neuropsychopharmacol 34, 2733–2745 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2009.114

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2009.114

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

NAPE-PLD deletion in stress-TRAPed neurons results in an anxiogenic phenotype

Translational Psychiatry (2023)

-

Fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibition alleviates anxiety-like symptoms in a rat model used to study post-traumatic stress disorder

Psychopharmacology (2023)

-

The effects of cannabis and cannabinoids on the endocrine system

Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders (2022)

-

CB1R activation in nucleus accumbens core promotes stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking by elevating extracellular glutamate in a drug-paired context

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Basolateral amygdala CB1 receptors gate HPA axis activation and context-cocaine memory strength during reconsolidation

Neuropsychopharmacology (2021)