Abstract

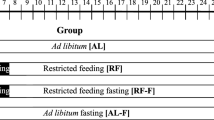

Circadian rhythms of behavior and physiology can be entrained by daily cycles of restricted food availability, but the pathways that mediate food entrainment are unknown. The dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus (DMH) is critical for the expression of circadian rhythms and receives input from systems that monitor food availability. Here we report that restricted feeding synchronized the daily rhythm of DMH activity in rats such that c-Fos expression in the DMH was highest at scheduled mealtime. During food restriction, unlesioned rats showed a marked preprandial rise in locomotor activity, body temperature and wakefulness, and these responses were blocked by cell-specific lesions in the DMH. Furthermore, the degree of food entrainment correlated with the number of remaining DMH neurons, and lesions in cell groups surrounding the DMH did not block entrainment by food. These results establish that the neurons of the DMH have a critical role in the expression of food-entrainable circadian rhythms.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Krieger, D.T. Food and water restriction shifts corticosterone, temperature, activity and brain amine periodicity. Endocrinology 95, 1195–1201 (1974).

Bolles, R.C. & Stokes, L.W. Rat's anticipation of diurnal and a-diurnal feeding. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 60, 290–294 (1965).

Boulos, Z., Rosenwasser, A.M. & Terman, M. Feeding schedules and the circadian organization of behavior in the rat. Behav. Brain Res. 1, 39–65 (1980).

Stephan, F.K. Limits of entrainment to periodic feeding in rats with suprachiasmatic lesions. J. Comp. Physiol. [A] 143, 401–410 (1981).

Stephan, F.K. Phase shifts of circadian rhythms in activity entrained to food access. Physiol. Behav. 32, 663–671 (1984).

Stephan, F.K. Resetting of a feeding-entrainable circadian clock in the rat. Physiol. Behav. 52, 985–995 (1992).

Inouye, S.I. Restricted daily feeding does not entrain circadian rhythms of the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the rat. Brain Res. 232, 194–199 (1982).

Damiola, F. et al. Restricted feeding uncouples circadian oscillators in peripheral tissues from the central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Dev. 14, 2950–2961 (2000).

Hara, R. et al. Restricted feeding entrains liver clock without participation of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Cells 6, 269–278 (2001).

Stokkan, K.A., Yamazaki, S., Tei, H., Sakaki, Y. & Menaker, M. Entrainment of the circadian clock in the liver by feeding. Science 291, 490–493 (2001).

Schibler, U., Ripperger, J. & Brown, S.A. Peripheral circadian oscillators in mammals: time and food. J. Biol. Rhythms 18, 250–260 (2003).

Lamont, E.W., Diaz, L.R., Barry-Shaw, J., Stewart, J. & Amir, S. Daily restricted feeding rescues a rhythm of period2 expression in the arrhythmic suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuroscience 132, 245–248 (2005).

Krieger, D.T., Hauser, H. & Krey, L.C. Suprachiasmatic nuclear lesions do not abolish food-shifted circadian adrenal and temperature rhythmicity. Science 197, 398–399 (1977).

Stephan, F.K. Entrainment of activity to multiple feeding times in rats with suprachiasmatic lesions. Physiol. Behav. 46, 489–497 (1989).

Stephan, F.K. Circadian rhythm dissociation induced by periodic feeding in rats with suprachiasmatic lesions. Behav. Brain Res. 7, 81–98 (1983).

Stephan, F.K., Swann, J.M. & Sisk, C.L. Entrainment of circadian rhythms by feeding schedules in rats with suprachiasmatic lesions. Behav. Neural Biol. 25, 545–554 (1979).

Watts, A.G., Swanson, L.W. & Sanchez-Watts, G. Efferent projections of the suprachiasmatic nucleus: I. Studies using anterograde transport of Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 258, 204–229 (1987).

Watts, A.G. & Swanson, L.W. Efferent projections of the suprachiasmatic nucleus: II. Studies using retrograde transport of fluorescent dyes and simultaneous peptide immunohistochemistry in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 258, 230–252 (1987).

Chou, T.C. et al. Critical role of dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus in a wide range of behavioral circadian rhythms. J. Neurosci. 23, 10691–10702 (2003).

Lu, J. et al. Contrasting effects of ibotenate lesions of the paraventricular nucleus and subparaventricular zone on sleep-wake cycle and temperature regulation. J. Neurosci. 21, 4864–4874 (2001).

Thompson, R.H. & Swanson, L.W. Organization of inputs to the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus: a reexamination with Fluorogold and PHAL in the rat. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 27, 89–118 (1998).

Elmquist, J.K., Elias, C.F. & Saper, C.B. From lesions to leptin: hypothalamic control of food intake and body weight. Neuron 22, 221–232 (1999).

Chou, T.C. et al. Afferents to the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus. J. Neurosci. 22, 977–990 (2002).

Simerly, R.B. & Swanson, L.W. The organization of neural inputs to the medial preoptic nucleus of the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 246, 312–342 (1986).

Thompson, R.H., Canteras, N.S. & Swanson, L.W. Organization of projections from the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus: a PHA-L study in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 376, 143–173 (1996).

Elmquist, J.K., Ahima, R.S., Elias, C.F., Flier, J.S. & Saper, C.B. Leptin activates distinct projections from the dorsomedial and ventromedial hypothalamic nuclei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 741–746 (1998).

Choi, S., Wong, L.S., Yamat, C. & Dallman, M.F. Hypothalamic ventromedial nuclei amplify circadian rhythms: do they contain a food-entrained endogenous oscillator? J. Neurosci. 18, 3843–3852 (1998).

Inouye, S.T. Ventromedial hypothalamic lesions eliminate anticipatory activities of restricted daily feeding schedules in the rat. Brain Res. 250, 183–187 (1982).

Krieger, D.T. Ventromedial hypothalamic lesions abolish food-shifted circadian adrenal and temperature rhythmicity. Endocrinology 106, 649–654 (1980).

Saper, C.B., Lu, J., Chou, T.C. & Gooley, J. The hypothalamic integrator for circadian rhythms. Trends Neurosci. 28, 152–157 (2005).

Mistlberger, R. & Rusak, B. Food anticipatory circadian rhythms in paraventricular and lateral hypothalamic lesioned rats. J. Biol. Rhythms 3, 277–292 (1988).

Landry, G.J., Simon, M., Webb, I.C. & Mistlberger, R.E. Persistence of a behavioral food anticipatory circadian rhythm following dorsomedial hypothalamic ablation in rats. Am. J. Physiol. published online January 19 2006 (10.1152/ajpregu.00874.2005).

Abe, M. et al. Circadian rhythms in isolated brain regions. J. Neurosci. 22, 350–356 (2002).

Angeles-Castellanos, M., Aguilar-Roblero, R. & Escobar, C. c-Fos expression in hypothalamic nuclei of food-entrained rats. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 286, R158–R165 (2004).

Zigman, J.M. & Elmquist, J.K. Minireview: from anorexia to obesity—the yin and yang of body weight control. Endocrinology 144, 3749–3756 (2003).

Fulwiler, C.E. & Saper, C.B. Subnuclear organization of the efferent connections of the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. Brain Res. 319, 229–259 (1984).

Davidson, A.J., Cappendijk, S.L. & Stephan, F.K. Feeding-entrained circadian rhythms are attenuated by lesions of the parabrachial region in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 278, R1296–R1304 (2000).

Comperatore, C.A. & Stephan, F.K. Effects of vagotomy on entrainment of activity rhythms to food access. Physiol. Behav. 47, 671–678 (1990).

Moreira, A.C. & Krieger, D.T. The effects of subdiaphragmatic vagotomy on circadian corticosterone rhythmicity in rats with continuous or restricted food access. Physiol. Behav. 28, 787–790 (1982).

Fei, H. et al. Anatomic localization of alternatively spliced leptin receptors (Ob-R) in mouse brain and other tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 7001–7005 (1997).

Elmquist, J.K., Bjorbaek, C., Ahima, R.S., Flier, J.S. & Saper, C.B. Distributions of leptin receptor mRNA isoforms in the rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 395, 535–547 (1998).

Mitchell, V. et al. Comparative distribution of mRNA encoding the growth hormone secretagogue-receptor (GHS-R) in Microcebus murinus (Primate, lemurian) and rat forebrain and pituitary. J. Comp. Neurol. 429, 469–489 (2001).

Mistlberger, R.E. & Marchant, E.G. Enhanced food-anticipatory circadian rhythms in the genetically obese Zucker rat. Physiol. Behav. 66, 329–335 (1999).

Sherin, J.E., Shiromani, P.J., McCarley, R.W. & Saper, C.B. Activation of ventrolateral preoptic neurons during sleep. Science 271, 216–219 (1996).

Lu, J., Greco, M.A., Shiromani, P. & Saper, C.B. Effect of lesions of the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus on NREM and REM sleep. J. Neurosci. 20, 3830–3842 (2000).

Akiyama, M. et al. Reduced food anticipatory activity in genetically orexin (hypocretin) neuron-ablated mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 20, 3054–3062 (2004).

Mieda, M. et al. Orexin neurons function in an efferent pathway of a food-entrainable circadian oscillator in eliciting food-anticipatory activity and wakefulness. J. Neurosci. 24, 10493–10501 (2004).

Morrison, S.F. Central pathways controlling brown adipose tissue thermogenesis. News Physiol. Sci. 19, 67–74 (2004).

Paxinos, G. & Watson, C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (Academic Press, San Diego, 1998).

Gooley, J.J., Lu, J., Fischer, D. & Saper, C.B. A broad role for melanopsin in nonvisual photoreception. J. Neurosci. 23, 7093–7106 (2003).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Q. Ha and M. Ha for superb technical assistance. This research was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health to C.B.S. (HL60292) and J.J.G. (MH67413).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Fig. 1

The daily rhythm of c–Fos in the DMH realigns with a restricted daytime meal. (PDF 388 kb)

Supplementary Fig. 2

DMH lesions block the preprandial rise in locomotor activity, body temperature, and wakefulness. (PDF 2156 kb)

Supplementary Fig. 3

Camera lucida drawings of ibotenic acid–induced lesions in the hypothalamus. (PDF 975 kb)

Supplementary Fig. 4

Lesions in the VMHdm do not abolish food entrainment. (PDF 538 kb)

Supplementary Fig. 5

Parabrachial nucleus lesions do not block food entrainment. (PDF 726 kb)

Supplementary Fig. 6

The DMH plays a critical role in the expression of SCN− and food–entrainable rhythms. (PDF 969 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gooley, J., Schomer, A. & Saper, C. The dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus is critical for the expression of food-entrainable circadian rhythms. Nat Neurosci 9, 398–407 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1651

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1651

This article is cited by

-

The intersection between ghrelin, metabolism and circadian rhythms

Nature Reviews Endocrinology (2024)

-

AgRP neurons encode circadian feeding time

Nature Neuroscience (2024)

-

Activity-based anorexia animal model: a review of the main neurobiological findings

Journal of Eating Disorders (2021)

-

The deletion of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors expressing neurons in the dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus disrupts the diurnal feeding pattern and induces hyperphagia and obesity

Nutrition & Metabolism (2021)

-

Sleep dysregulation in binge eating disorder and “food addiction”: the orexin (hypocretin) system as a potential neurobiological link

Neuropsychopharmacology (2021)