Abstract

Pressure-induced amorphization (PIA) and thermal-driven recrystallization have been observed in many crystalline materials. However, controllable switching between PIA and a metastable phase has not been described yet, due to the challenge to establish feasible switching methods to control the pressure and temperature precisely. Here, we demonstrate a reversible switching between PIA and thermally-driven recrystallization of VO2(B) nanosheets. Comprehensive in situ experiments are performed to establish the precise conditions of the reversible phase transformations, which are normally hindered but occur with stimuli beyond the energy barrier. Spectral evidence and theoretical calculations reveal the pressure–structure relationship and the role of flexible VOx polyhedra in the structural switching process. Anomalous resistivity evolution and the participation of spin in the reversible phase transition are observed for the first time. Our findings have significant implications for the design of phase switching devices and the exploration of hidden amorphous materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Materials that contain no long-range structural order (for example, glass or amorphous phase) are fundamentally interesting to both the basic sciences and for practical industrial applications1,2. Glass, which has been considered a metastable and kinetically frozen disordered state, can be synthesized by rapidly quenching a melt from high temperature to prevent crystallization. Another frequently reported but distinct approach to amorphous phases or glasses is via pressure-induced amorphization (PIA)3,4. The disordering process in PIA differs significantly from the thermally-induced disorder in substance melting, where a much higher density is expected. PIA has been observed in many materials such as ice5,6,7, α-quartz SiO2 (refs 8, 9, 10), AlPO4 (ref. 11), R-Al5Li3Cu (ref. 12), and so on, and is widely accepted as an important condensed matter phenomenon. In some cases, mechanical instability caused by ‘thermodynamic melting’ and increased atomic coordination are considered to contribute most to PIA8,13. While in other cases, such as ZrW2O8, negative thermal expansion (NTE) may have some possible connection with the PIA14,15,16,17. However, determining the underlying mechanism still remains one of the most fascinating challenges and some recent evidence even shows that previously reported PIAs were due to the fragmentation of bulky particles into nanocrystals and strongly correlated pressurization environments3. Furthermore, new high-density PIA generated materials are expected to drive new theoretical approaches for modelling this phenomenon, which is essential for discovering their practical applications. Recently, pressure-induced crystallization revealed the topological ordering in metallic glasses at room temperature18. But upon heating, the recovered amorphous phase tends to return to its stable crystalline phase to minimize the system’s energy, depending on the kinetic barrier it needs to overcome. Such examples include the main group compounds SnI4, LiKSO4, Ca(OH)2, clathrasils and berlinite AlPO4 (refs 19, 20, 21, 22, 23). Molecular dynamics calculations on PIA-AlPO4 (ref. 23) showed that the presence of non-deformable, fourfold coordinated PO4 interlinking units in the crystal structure have a crucial role in the reversible amorphization and crystallization phase transition, where they acted as templates around which the original structure and even the original orientation were restored23,24. So far, reversible PIA has only been observed in the above-mentioned main group compounds, where only the lattice participates in the intriguing structure transformation. The study of more variables (that is, charge, spin and orbital) involved in PIA and the subsequent recrystallization processes could potentially allow a more comprehensive understanding of the order–disorder transformation mechanism and the electronic behaviour in highly disordered materials.

Discovering new external-stimuli responsive compounds with switchable ground states is a major objective in material science because these materials often lead to unusual phenomena or useful functionalities25,26. When considering PIA materials as metastable and dense phases distinct from their crystalline forms, it is important to achieve a controllable phase switching between either the PIA glass and their crystalline polymorphisms or even between two PIA phases.

In this work, we report a reversible structural switch between the metastable crystalline phase VO2(B) and its PIA glass, in the form of nanosheets. The phase switch between these two metastable phases is realized with low-pressure compression (∼20 GPa) and relative low-temperature annealing (∼200 °C). The phase transformation and underlying mechanism is thoroughly studied using in situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction (XRD), infrared, Raman spectroscopy and theoretical calculations. High-pressure electronic transport properties and magnetic properties are also studied to provide direct evidence of the participation of charge and spin during the phase transformation, for the first time. Our findings may provide a new research platform for the exploration of novel amorphous materials and phenomena under controllable external stimuli.

Results

Material and crystal structure

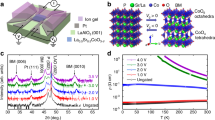

There are several crystalline phases of VO2 at ambient conditions: VO2(A), VO2(B), VO2(M), VO2(R) and other metastable phases27,28,29,30,31. Among them, VO2(M) is the thermodynamically stable phase but it undergoes an insulator-to-metal transition (ITM) under high pressure to a metallic phase VO2(R) around room temperature. The structures and physical properties of the phases differ significantly due to the distinct coordination environments of V atoms in the VOx polyhedra, the V4+–V4+ interactions and the various cross linking manners (Supplementary Fig. 1). VO2(B) is a thermodynamically metastable phase adopting an anisotropic layered structure, and is frequently used as a battery material32. Its unique structural features, such as well-embedded layers and hierarchical V–O bonding, also make VO2(B) an interesting candidate for structural stability studies under high pressure. In this work, VO2(B) nanosheets were synthesized from high pure V2O5 raw material via a hydrothermal route with citric acid as the reducing agent33. The product consisted of well-shaped nanosheets that were several micrometres in length/width and tens of nanometres in thickness, and its single crystal nature is proven by the well-arranged spots in the selected-area electron diffraction pattern (Fig. 1a,b). The structure of VO2(B) is characterized by the layered feature in the bc plane with a twofold connected O1 atom between the layers (Fig. 1c). Less electron charge distribution between the layers makes the [100] direction more compressible, and there is also a distinct gap along the [001] direction. Overall, the VO2(B) structure has a hierarchical structure consisting of condensed face-sharing VOx polyhedra. More structural features of VO2(B) along different axes are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

(a) Bright field TEM images of VO2(B) nanosheets. Scale bar, 2 μm. (b) Selected-area electron diffraction of VO2(B) nanosheets along the [010] zone axis showing its single crystal nature. Scale bar, 5 nm−1. (c) Crystal structure of VO2(B) showing a dense packed vanadium–oxygen layer in the bc plane and ac plane with hierarchical V–O bonding. The O1 atoms with shortest V=O bonds are highlighted in green.

PIA at room temperature

The in situ synchrotron XRD patterns of VO2(B) nanosheets, as a function of pressure without pressure transition medium, are shown in Fig. 2a. There was no structural transition until the onset of amorphization around 20 GPa. The XRD pattern at ambient conditions is well-indexed with the monoclinic space group C2/m and lattice constants a=12.054(3) Å, b=3.693(1) Å, c=6.424(2) Å and β=106.96(1)°, in good agreement with other reported values12,13. As discussed above, from a structural chemistry viewpoint, the VO2(B) nanosheet was expected to show an anisotropic compressibility under pressure. The lattice parameters at various pressures before PIA were obtained by Reitveld refinements of these XRD patterns, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. During compression, the diffraction peaks became broader and weaker from about 17 GPa, and completely vanished around 20 GPa, indicating the loss of long-range ordering in the pressure-amorphized state. To check the shear and non-hydrostaticity effect on the PIA, we repeated the experiments using neon and helium as pressure-transmitting medium (PTM) for comparison. In all cases, the PIA process occurred and the amorphous PIA-VO2(B) was preserved to ambient conditions after releasing pressure. In contrast, no PIA was observed in the thermal-stable VO2(M) phase up to 55 GPa34.

(a) In situ synchrotron XRD patterns of VO2(B) as a function of pressure show the pressure-induced amorphization happened around 21 GPa. (b) Infrared spectra taken between ambient pressure and 23.6 GPa. (c) Raman spectra taken between 1.4 and 22.7 GPa. (d,e) Detailed infrared and Raman spectra at the starting, highest pressure and recovered states.

Spectroscopic techniques can probe the short-range structural features of local atomic coordinates. We employed infrared and Raman spectroscopy to examine the local structural evolution of VO2(B) nanosheets during compression and decompression. Figure 2b displays the infrared spectrum of VO2(B) as a function of pressure up to 23.6 GPa. Characteristic peaks located around 1,000 cm−1 (at ambient conditions) are assigned to the shortest V4+=O1 bonds pointing perpendicularly into the bc interlayer. The mode frequency barely shifted (<50 cm−1) towards high wave numbers upon compression. However, the broadening of the vibrational mode increases with pressure, and finally merging with other broad bands down to 600 cm−1 is a more profound change. These were associated with angle deformations of the VOx polyhedral upon compression and eventually a disordered state resulted in amorphization. This evidence clearly indicates the nature of the degenerated chemical environments of oxygen around the V4+ centres. As pressure increases, the enhanced oxygen coordination around vanadium atoms in VO2(B) is expected to lead to the dynamical lattice instability, which triggers the PIA. It is interesting that the preserved PIA-VO2(B) has similar local vibrational modes to the pristine VO2(B) nanosheets, indicating that the short-range structure features of VO2(B) are preserved, as indicated in Fig. 2d. Moreover, Raman spectroscopy was employed to evaluate the contribution of the electron–phonon interactions to the PIA phase transition of VO2(B) (Fig. 2c). At low pressure, only five bands near 198, 260, 570, 780 and 1,020 cm−1 were observed with moderate intensity in the VO2(B) nanosheets. Typically, the peak located at 1,020 cm−1 can be assigned to the V4+=O1 stretching modes of terminal oxygen atoms. Upon compression above 10 GPa, all the bands weakened and finally vanished. Meanwhile, broad bands between 600 and 1,000 cm−1 were observed corresponding with the PIA process. As anticipated, similarly to the infrared results, all of the atomic location information was preserved with a more disordered state as indicated by the broadening of the vibrational bands in Fig. 2e, which closely resembles the Raman changes during the ITM process from VO2(M) to metallic VO2(R).

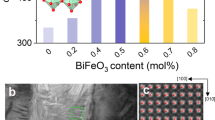

Thermal-driven recrystallization and the phase diagram

The PIA-VO2(B) phase returns to the pristine VO2(B) structure upon annealing at relatively low temperature (∼200 °C by in situ annealing experiment) for a short time (∼5 min). Figure 3 shows the XRD pattern of the starting VO2(B) nanosheets and PIA-VO2(B) before and after annealing at 250 °C (50 °C above the critical temperature to guarantee a complete recrystallization). To ensure that the PIA process was achieved, a higher pressure of 31.5 GPa (far beyond the PIA starting point) was applied. As discussed, the loss of the X-ray diffraction peaks in the recovered PIA-VO2(B) sample suggests the absence of long-range ordering. After annealing at 250 °C in a vacuum environment for 5 min, surprisingly, we noticed that the diffraction pattern from this heat-treated sample showed the same powder characteristic peaks as the VO2(B) phase with a monoclinic space group C2/m, lattice constants a=12.065(3) Å, b=3.650(9) Å, c=6.482(11) Å and β=107.53(7)° (Supplementary Fig. 4) and a little expanded cell volume (273.5 Å3 versus 272.2 Å3 of the pristine sample). This structure switching phenomenon is distinct from the previously reported reversible PIA phenomena with the following characteristics:23,24 (1) In the cases of some so-called ‘memory glasses’, such as AlPO4, the PIA phases can be restored to their initial crystalline structures spontaneously at room temperature once pressure is released. In contrast, PIA-VO2(B) can exist as a metastable, high density, intermediate phase, and the small active energy barrier between PIA-VO2(B) and crystalline VO2(B) enables feasible control of the phase switch; (2) The reversible PIA and recrystallization processes are guaranteed to occur between VO2(B) and PIA-VO2(B) (except some thermodynamically stable phases such as VO2(M)), due to the relatively low operating temperature (compression at room temperature and annealing at ∼200 °C). The illustration that dynamically low temperature can hinder both the pressure- and temperature-induced traditional phase transitions indicates that more hidden phase relationships may be discovered at low temperature. (3) Moreover, the crystal structure of VO2(B) is built up of a 3d metal V4+ (S=1/2) based framework. Both the atomic coordination preference of the distorted VOx polyhedra and possible electron/magnetic interactions within the crystal lattice may contribute to the reversible structure transformation. The latter will be discussed in detail in the electron transport property section.

(a) XRD pattern of the pristine VO2(B) nanosheets; (b) XRD pattern of PIA-VO2(B) recovered from 31.5 GPa; (c) XRD pattern of PIA-VO2(B) after annealing at 250 °C in a vacuum for 5 min. Bottom: theoretical Bragg lines of VO2(B) and VO2(M). The peaks of (c) are indexed with the monoclinic space group C2/m and lattice constants: a=12.065(3) Å, b=3.650(9) Å, c=6.482(11) Å and β=107.53(7)°.

Recent investigations by more powerful and precise techniques show that PIA is highly related to the pressurization environments and crystallinity of the starting materials. Some of the phenomena previously reported as PIA were likely due to either the formation of multiple polymorphic phases, or even that the PIA process did not occur if single crystal samples were adopted or more hydrostatic compression was applied8,9,10,35. To check this issue in the VO2(B) system and obtain the exact conditions where the phase transformations occurred, in situ powder XRD experiments were conducted. Firstly, the PIA process of VO2(B) with different PTMs were evaluated. Figure 4a displays the integrated (110) peak intensity of VO2(B) as a function of pressure without a PTM or with Ne, He as the PTMs. VO2(B) nanosheets under all of these three conditions showed the onset of PIA around 10 GPa. Without PTM, the PIA process accomplished concluded around 20 GPa or a little higher when a better hydrostatic pressure condition was given (30 and 35 GPa for neon and helium as PTMs, respectively). This indicates that the PIA of VO2(B) is somewhat related to the deviatoric stress36, which is reasonable considering the hierarchical structural features of VO2(B). Fortunately, the value of 20 GPa was low enough to obtain bulk samples using a large volume press apparatus for routine magnetism measurements. Figure 4b shows the (110) peak intensity of PIA-VO2(B) as a function of the annealing temperature. The recrystallization starts from as low as 100 °C and completes around 200 °C. The relatively low annealing temperature makes the switch between PIA-VO2(B) and crystalline VO2(B) feasible. The pressure- and temperature-induced phase transformations of VO2(B) nanosheets observed in our work are summarized schematically in Fig. 4c with other known VO2 crystalline phases. Under compression at room temperature, the expected phase transformation from metastable VO2(B) to thermodynamically stable VO2(M) does not occur. This indicates a higher kinetic barrier (Ebarrier2) of atomic diffusion, and the large surface energy from the nanosheets at room temperature. The formed high-density PIA-VO2(B) returned to the pristine metastable VO2(B) structure after short-time annealing at relatively low temperature (250–300 °C, 10 min), instead of transforming to the thermodynamically stable VO2(M) phase. This indicates a relatively low kinetic barrier transforming to metastable VO2(B) compared with the high crystallization energy associated with the VO2(M) phase and demonstrate that hidden structural switching can be realized using a compression and heating route, as shown in Fig. 4c. Such an intriguing phase transition is the first ever example observed in a 3d metal involved material. Similar structure switching behaviour was observed in PbTe nanoparticles37, but in our case the switching between two thermally metastable phases was highly dependent on the temperature parameter. We believe that the key factor enabling this reversible phase transformation is the temperature, which is kinetically low enough for sufficient atomic mobility, which thus causes the elastic deformation of the structure. However, when the annealing temperature was high enough to surpass the VO2(B) to VO2(M) phase transition temperature (∼550 °C)33, the PIA-VO2(B) can also transfer to VO2(M) via the intermediate VO2(B) phase.

(a) The integrated (110) peak intensity of VO2(B) as a function of pressure under three different compression conditions. (b) The integrated (110) peak intensity of PIA-VO2(B) as a function of the annealing temperature. The error bars in (b) indicate the s.d. values of the integrated peak intensity at a given pressure. (c) Density-energy scheme of the VO2 system and the reversible structure switching. Blue and red arrows show the thermal dynamically allowed phase transitions between VO2(B) and PIA-VO2(B); The black arrow shows the dynamically hindered transition from VO2(B) to VO2(M) under compression.

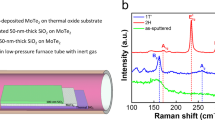

First-principles calculation of the pressure-phase relationship

The experimental results evidently show the pressure- and thermal-controlled structure switching of VO2(B) nanosheets. To provide further thermodynamic and kinetic insight into the pressure-phase relationship during the phase transformation, we performed density functional theory (DFT) simulations using CASTEP code38. Detailed calculation information is provided in the Supplementary Materials. Total energy calculations demonstrate that VO2(M) is the most stable phase of VO2 under ambient pressure at room temperature, and that VO2(M) and VO2(R) have a higher density than VO2(A) and VO2(B) (Supplementary Fig. 5). Upon compression up to 100 GPa, VO2(B) was thermodynamically metastable compared with VO2(M) and VO2(R). However, no crystal-to-crystal phase transition from VO2(B) to VO2(M) or VO2(R) was observed, due to the high-kinetic energy barrier between them at room temperature. Figure 5 shows both the calculated pressure–volume equations of states of the four crystalline VO2 phases and the experimental data of VO2(B) nanosheets upon compression. The experimental data of the VO2(B) nanosheets exhibit a larger unit cell volume than those theoretically predicted, which is reasonable considering the nanosheet surface defects. This large cell volume falls into the traditional VO2 glass region. Upon compressing to around 20 GPa, the VO2(B) nanosheets passed through the ideal pressure–volume boundary of VO2(B) and became amorphous with a higher density. The stable region of PIA-VO2(B) is indicated in Fig. 5, which passed between VO2(B) and VO2(M) under high pressure. Several possibilities have been proposed for the underlying mechanism of a PIA process, such as the mechanical instability beyond the Born stability conditions and ‘thermodynamic melting’1,9. In the case of VO2(B), we propose that the combination of kinetic hindrance of the phase transformation to thermodynamically stable VO2(M) and the increased atomic coordination are the driving forces of PIA. Upon moderate temperature annealing, the preference of VOx polyhedra in thermodynamically metastable PIA-VO2(B) drives the structure to return to the pristine VO2(B).

Squares present the simulated results based on DFT calculations of VO2(A), VO2(B), VO2(M) and VO2(R) upon compression up to 60 GPa; asterisks are the experimental data of the VO2(B) nanosheets. The equation of state of VO2(B) nanosheets has the parameters: zero-pressure volume V0=34.325 Å3 per VO2, bulk modulus B0=129.1 GPa and bulk modulus pressure derivative B0′=4.

In the P–V phase diagram, one can clearly see the difference between PIA-VO2(B) and VO2 glass. It is important to note that other hidden phases of VO2 may exist, either in the low-density glass range or the high-density pressure-induced amorphous range. In this study, we observed profound structure switching behaviour of PIA-VO2(B) at kinetically moderate temperatures, which demonstrates an interesting phenomenon of how temperature has a critical role in governing phase transformations under high pressure. The exploration of yet more interesting physical properties related to high density VO2 glass with a short-range order may greatly boost the development of condensed matter science.

Discussion

VO2 phases as the famous strongly correlated family always shows interesting magnetic and electric properties. To gain more insight into the participation of charge and spin interactions during the PIA, in situ electrical resistance within a diamond anvil cell (DAC) and ex situ magnetic susceptibility measurements (using an amorphized sample synthesized by a large volume press apparatus) were performed. Figure 6 shows the resistance change during compression and decompression, and those at 7.5 and 26 GPa (before and after amorphization) as a function of temperature. At the first stage (P<10 GPa), the resistance drop can be associated with the broadening and partial overlapping of the valence and conduction bands, caused by the normal pressure-induced shortening of V–V distances and bending of the V–O bonds. A steep increase in the resistance, which is caused by the onset and completion of the PIA, dominates the profile between 10 and 18 GPa. During the PIA process, point defects accompany the breaking of the long-range order, and thus the electron transport is suppressed by these increased defects, which serve as scattering centres. After the PIA process, band overlapping proceeds, as revealed by the continuous decrease of the electrical resistance, and finally drops to 30 GPa; nearly the same level as the crystalline VO2(B) before PIA. However, after decompression, the resistance increases by two orders of magnitude than the pristine VO2(B) sample (Fig. 6b), which indicates a reinforced electronic localization in PIA-VO2(B). The temperature dependence of the electric resistance before and after the PIA process (7.5 and 26.0 GPa) proves that PIA-VO2(B) remains a semiconductor but has poorer electrical conductivity (Fig. 6c). We also fabricated PIA-VO2(B) samples using a large volume press apparatus at room temperature and 20 GPa. The decrease of the effective Bohr magnetic moment in PIA-VO2(B) from 1.35μB to 1.15μB per V4+, as derived from the ex situ magnetic susceptibility measurement, suggests that the electron localization may be due to the formation of more V–V pairs/dimers (Supplementary Fig. 6). More investigations are required to further probe the role of charge and spin in the PIA phenomenon and structure memory of VO2(B) nanosheets.

In conclusion, we report a precise control of the structure switching between crystalline and pressure-induced amorphous phases in VO2(B) nanosheets for the first time. The PIA-VO2(B) has no long-range periodicity, but preserves the inherited VOx polyhedral from VO2(B) with highly distorted local ordering. Upon moderate temperature annealing, these VOx polyhedra release excess energy and restore the pristine long-range periodicity. Spectral evidence and DFT calculations provide additional insight into the phase relationship between crystalline VO2 phases and PIA-VO2(B) glass. The dynamically moderate annealing temperature provides a key mechanism of energetic control on the hidden reversible amorphization of metastable VO2(B). Preliminary evidence for the participation of charge and spin interactions during PIA were also observed for the first time. The robust control of the phase transition between the metastable crystalline VO2(B) phase and the PIA-VO2(B) amorphous phase, via compression and low-temperature annealing, reveals the structure switching behaviour within a tetravalent vanadium-based material for the first time. This highlights exploration of thermodynamically hindered phase transformations with pressure and temperature tuning. Further investigations on the physical mechanism behind the phenomenon are expected, including orbital, electron and magnetic interactions.

Methods

Sample preparation

VO2(B) nanosheets were synthesized from high pure V2O5 raw material via a hydrothermal route, with citric acid as the reducing agent. Briefly, 0.182 g V2O5 powder (1 mmol) and 0.288 g citric acid (1.5 mmol) were added into 20 ml distilled water and continuously stirred to obtain the precursor. The precursor was then transferred into a Teflon-lined autoclave (25 ml capacity, 80% filling). The autoclave was heated to 200 °C at a rate of 3 °C min−1 and maintained at 200 °C for 5 h, followed by air cooling to room temperature by switching the power off. The resulting precipitates were washed with deionized water and dried at 80 °C overnight. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) techniques were applied to check the morphology of the as-synthesized nanosheets at ambient pressure.

In situ high-pressure characterizations

A symmetric DAC was employed to generate high pressure. A stainless steel gasket was pre-indented to a 40 μm thickness, followed by laser-drilling the central part to form a 120 μm diameter hole to serve as the sample chamber. Pre-compressed VO2(B) powder pellets and a small ruby ball were loaded in the chamber. Helium or neon was used as the pressure-transmitting medium and the pressures were determined by the ruby fluorescence method39. The in situ high-pressure angular-dispersive XRD experiments were carried out at the 16BM-D station of the High-Pressure Collaborative Access Team (HPCAT) at the Advanced Phonon Source (APS), Argonne National Laboratory (ANL). A focused monochromatic X-ray beam about 5 μm in diameter (FWHM) and with wavelengths of 0.4246 Å was used for the diffraction experiments. The diffraction data were recorded by a MAR345 image plate and processed with the Fit2D programme. High-pressure infrared spectroscopic experiments were performed at the U2A beamline of National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS), Brookhaven National Laboratory and the mid-IR beamline of the Canadian Light Source. The infrared spectra were collected in transmission mode by a Bruker FTIR spectrometer using a nitrogen-cooled mid-band MCT (MCT-A) detector. The recorded frequencies were in the range of 600–8,000 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1. High-pressure Raman spectra were measured by a Raman spectrometer with a 532.1 nm excitation laser at HPCAT.

For the ex situ annealing experiments, the PIA-VO2(B) samples were removed with the gaskets after depressurization. They were then annealed at different temperatures (200, 250, 300, 350, 400, 450, 500, 550 °C) each for 5 min within a vacuum furnace, and the resulting phases were checked with synchrotron XRD. While in the in situ annealing experiments, the bulky PIA-VO2(B) sample was made using a large volume press apparatus and sealed in a glass tube. Then XRD patterns were taken at 30, 60, 90, 120, 160, 190 and 220 °C with electric heating, respectively. The holding time at each temperature was 5 min. Structure refinements were performed with the FULLPROF programme40.

Resistance and magnetic susceptibility measurements

In situ electrical resistance was measured by a four-probe resistance measurement system consisting of a Keithley 6,221 current source, a 2182A nanovoltmeter and a 7,001 voltage/current switch system. A DAC device was used to generate pressures up to 30 GPa, and a cubic boron nitride layer was inserted between the steel gasket and diamond anvil to provide electrical insulation between the electrical leads and gasket. Four gold wires were arranged to contact the sample in the chamber for resistance measurements. For the magnetism measurement, 0.1 g sample was made using a large volume press apparatus at 20 GPa for 1 h at room temperature. The DC magnetic susceptibility was measured using a SQUID magnetometer (Quantum Design) with an applied magnetic field of 500 Oe.

DFT calculations

Total energy and pressure–volume equations of state for the four VO2 crystalline phases were calculated at the atomic level using the first-principles plane-wave pseudopotential method41 based on the density functional theory, with the CASTEP package38. The exchange-correlation function is described by the local density approximation42. The ion-electron interactions were modelled with ultrasoft pseudopotentials43 for all constituent elements, where the V 4s23d3 and O 2s22p4 electrons were treated as the valence electrons, respectively. The kinetic energy cut-off of 380 eV and Monkhorst-Pack k-point meshes44 spanning <0.04 Å−3 in the Brillouin zone were chosen. The starting structure models were obtained from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) for VO2(A), VO2(B), VO2(M) and VO2(R). The cell parameters and atomic positions within the unit cell of these four phases, under hydrostatic pressure ranging between 0 and 100 GPa (with the interval of 5 GPa), were fully optimized using the quasi-Newton method45. The convergence thresholds between the optimization cycles for energy change, maximum force, maximum stress, and maximum displacement were set as 5.0 × 10–6 eV per atom, 0.01 eV Å−1, 0.02 GPa and 5.0 × 10–4 Å, respectively. The optimization terminates when all of these criteria are satisfied. All these computational parameters were tested to ensure the sufficient accuracy for the present purposes.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Wang, Y. et al. Reversible switching between pressure-induced amorphization and thermal-driven recrystallization in VO2(B) nanosheets. Nat. Commun. 7:12214 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12214 (2016).

References

Mishima, O., Calvert, L. D. & Whalley, E. ‘Melting ice’ I at 77 K and 10 kbar: a new method of making amorphous solids. Nature 310, 393–395 (1984).

Yamanaka, T., Nagai, T. & Tsuchiya, T. Mechanism of pressure-induced amorphization. Z. Kristallogr. 212, 401–410 (1997).

Machon, D., Meersman, F., Wilding, M. C., Wilson, M. & McMillan, P. F. Pressure-induced amorphization and polyamorphism: inorganic and biochemical systems. Prog. Mater. Sci. 61, 216–282 (2014).

Sharma, S. M. & Sikka, S. K. Pressure induced amorphization of materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 40, 1–77 (1996).

Hemley, R. J., Chen, L. C. & Mao, H. K. New transformations between crystalline and amorphous ice. Nature 338, 638–640 (1989).

Mishima, O., Takemura, K. & Aoki, K. Visual observations of the amorphous-amorphous transition in H2O under pressure. Science 254, 406–408 (1991).

Tse, J. S. et al. The mechanisms for pressure-induced amorphization of ice Ih . Nature 400, 647–649 (1999).

McNeil, L. E. & Grimsditch, M. Pressure-amorphized SiO2 α-quartz: an anisotropic amorphous solid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 83–85 (1992).

Hemley, R. J., Jephcoat, A. P., Mao, H. K., Ming, L. C. & Manghnani, M. H. Pressure-induced amorphization of crystalline silica. Nature 334, 52–54 (1988).

Sato, T. & Funamori, N. Six-fold-coordinated amorphous polymorph of SiO2 under high pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 255502 (2008).

Jayaraman, A., Wood, D. L. & Mains, R. G. Sr High-pressure Raman study of the vibrational modes in AlPO4 and SiO2 (α-quartz). Phys. Rev. B 35, 8316–8321 (1987).

Winters, R. R. & Hammack, W. S. Pressure-induced amorphization of R-Al5Li3Cu: a structural relation among amorphous metals, quasi-crystals, and curved space. Science 260, 202–204 (1993).

Zhang, J. et al. Pressure-induced amorphization and phase transformations in β-LiAlSiO4 . Chem. Mater. 17, 2817–2824 (2005).

Keen, D. A. et al. Structural description of pressure-induced amorphization in ZrW2O8 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 225501 (2007).

Perottoni, C. A. & Jornada, J. A. H. Pressure-induced amorphization and negative thermal expansion in ZrW2O8 . Science 280, 886–889 (1998).

Varga, T. et al. Pressure-induced amorphization of cubic ZrW2O8 studied in situ and ex situ by synchrotron X-ray diffraction and absorption. Phys. Rev. B 72, 024117 (2005).

Arora, A. K., Okada, T. & Yagi, T. Structural analysis of pressurre-amorphized zirconium tungstate. Phys. Rev. B 81, 134103 (2010).

Zeng, Q. et al. Long-range topological order in metallic glass. Science 332, 1404–1406 (2011).

Fuji, Y., Kowaka, M. & Onodera, A. The pressure-induced metallic amorphous state of SnI4: I. A novel crystal-to-amorphous transition studied by x-ray scattering. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 18, 789–797 (1985).

Sankaran, H., Sikka, S. K., Sharma, S. M. & Chidambaram, R. Pressure-induced noncrystalline phase of LiKSO4 . Phys. Rev. B 38, 170–173 (1988).

Kruger, M. B., Williams, Q. & Jeanloz, R. Vibrational spectra of Mg(OH)2 and Ca(OH)2 under pressure. J. Chem. Phys. 91, 5910–5915 (1989).

Tse, J. S., Klug, D. D., Rlpmeester, J. A., Desgreniers, S. & Lagarec, K. The role of non-deformable units in pressure-induced reversible amorphization of clathrasils. Nature 369, 724–727 (1994).

Tse, J. S. & Klug, D. D. Structural memory in pressure-amorphized AlPO4 . Science 255, 1559–1561 (1992).

Kruger, M. B. & Jeanloz, R. Memory glass: an amorphous material formed from AlPO4 . Science 249, 647–649 (1990).

Lim, H. S., Kwak, D., Lee, D. Y., Lee, S. G. & Cho, K. UV-driven reversible switching of a roselike vanadium oxide film between superhydrophobicity and superhydrophilicity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 4128–4129 (2007).

Geyer, T., Born, P. & Kraus, T. Switching between crystallization and amorphous agglomeration of alkyl thiol-coated gold nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 128302 (2012).

Popuri, S. R. et al. VO2(A): reinvestigation of crystal structure, phase transition and crystal growth mechanisms. J. Solid State Chem. 213, 79–86 (2014).

Oka, Y., Yao, T., Yamamoto, N., Ueda, Y. & Hayashi, A. Phase transition and V4+–V4+ pairing in VO2(B). J. Solid State Chem. 105, 271–278 (1993).

Galy, J. & Miehe, G. Ab initio structures of (M2) and (M3) VO2 high pressure phases. Solid State Sci. t1, 433–448 (1999).

Leroux, C., Nihoul, G. & Van Tendeloo, G. From VO2(B) to VO2(R): Theoretical structures of VO2 polymorphs and in situ electron microscopy. Phys. Rev. B 57, 5111–5121 (1998).

Zhang, S. et al. From VO2(B) to VO2(A) nanobelts: first hydrothermal transformation, spectroscopic study and first principles calculation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 15873–15881 (2011).

Li, H., He, P., Wang, Y., Hosono, E. & Zhou, H. High-surface vanadium oxides with large capacities for lithium-ion batteries: from hydrated aerogel to nanocrystalline VO2(B), V6O13 and V2O5 . J. Mater. Chem. 21, 10999–11009 (2011).

Popuri, S. R. et al. Rapid hydrothermal synthesis of VO2(B) and its conversion to thermochromic VO2(M1). Inorg. Chem. 52, 4780–4785 (2013).

Bai, L. et al. Pressure-induced phase transitions and metallization in VO2 . Phys. Rev. B 91, 104110 (2015).

Hu, Q. Y. et al. Polymorphic phase transition mechanism of compressed coesite. Nat. Commun. 6, 6630 (2015).

Klotz, S., Chervin, J.-C., Munsch, P. & Marchand, G. L. Hydrostatic limits of 11 pressure transmitting media. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys 42, 075413 (2009).

Quan, Z. et al. Pressure-induced switching between amorphization and crystallization in PbTe nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 13, 3729–3735 (2013).

Clark, S. J. et al. First principles methods using CASTEP. Z. Kristallogr. 220, 567–570 (2005).

Mao, H. K., Xu, J. & Bell, P. M. Calibration of the ruby pressure gauge to 800 kbar under quasi-fydrostatic conditions. J. Geophys. Res. 91, 4673–4676 (1986).

Rodriguez-Carvajal, J. Recent advances in magnetic structure determination by neutron powder diffraction. Phys. B 192, 55–69 (1993).

Payne, M. C., Teter, M. P., Allan, D. C., Arias, T. A. & Joannopoulos, J. D. Iterative minimization techniques for ab initio total-energy calculations: molecular dynamics and conjugate gradients. Rev. Mod. Phys. 64, 1045–1097 (1992).

Ceperley, D. M. & Alder, B. J. Ground state of the electron gas by a stochastic method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 566–569 (1980).

Lin, J. S., Qteish, A., Payne, M. C. & Heine, V. Optimized and transferable nonlocal separable ab initio pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 47, 4174–4180 (1993).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special point for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Pfrommer, B. G., Cote, M., Louie, S. G. & Cohen, M. L. Relaxation of crystals with the quasi-Newton method. J. Comput. Phys. 131, 233–240 (1997).

Acknowledgements

The UNLV High Pressure Science and Engineering Center (HiPSEC) is a DOE-NNSA Center of Excellence supported by Cooperative Agreement DE-NA0001982. HPCAT operations are supported by DOE−NNSA under Award DE-NA0001974 and DOE-BES under Award DE-FG02-99ER45775, with partial instrumentation funding by NSF. U2A beamline was supported by National Science Foundation (EAR 1606856, COMPRES) and DOE/NNSA (DE-NA-0002006, CDAC). The gas loading was performed at GeoSoilEnviroCARS, APS, ANL, supported by EAR-1128799 and DE-FG02-94ER14466. The authors thank Q. Li (JLU), L. Bai (HPCAT), L. Tang, L. Yang and R. Ferry (HPSynC), D. Sneed and Q. Smith (UNLV) for their valuable suggestions and help in the experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Y. and Y.Z. conceived the project and designed the experiments. Y.W. and T.W. performed material synthesis, characterizations and high-pressure measurements. J.Z., M.P. and Z.L. performed IR measurements. M.H. and Y.F. synthesized the large volume amorphous sample. J.Z. and C.J. performed the magnetism measurements. L.K. and Z.L. performed the DFT calculation. Y.W., W.Y. and Y.Z. analyzed the data and co-wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-6 (PDF 730 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Zhu, J., Yang, W. et al. Reversible switching between pressure-induced amorphization and thermal-driven recrystallization in VO2(B) nanosheets. Nat Commun 7, 12214 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12214

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12214

This article is cited by

-

Towards Room Temperature Thermochromic Coatings with controllable NIR-IR modulation for solar heat management & smart windows applications

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Drastic enhancement of magnetic critical temperature and amorphization in topological magnet EuSn2P2 under pressure

npj Quantum Materials (2022)

-

Microwave assisted growth of highly oriented vanadium oxides nanostructures: structural, vibrational and electrical properties

Applied Physics A (2021)

-

Temperature-induced amorphization in CaCO3 at high pressure and implications for recycled CaCO3 in subduction zones

Nature Communications (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.