Abstract

Topological semimetals can support one-dimensional Fermi lines or zero-dimensional Weyl points in momentum space, where the valence and conduction bands touch. While the degeneracy points in Weyl semimetals are robust against any perturbation that preserves translational symmetry, nodal lines require protection by additional crystalline symmetries such as mirror reflection. Here we report, based on a systematic theoretical study and a detailed experimental characterization, the existence of topological nodal-line states in the non-centrosymmetric compound PbTaSe2 with strong spin-orbit coupling. Remarkably, the spin-orbit nodal lines in PbTaSe2 are not only protected by the reflection symmetry but also characterized by an integer topological invariant. Our detailed angle-resolved photoemission measurements, first-principles simulations and theoretical topological analysis illustrate the physical mechanism underlying the formation of the topological nodal-line states and associated surface states for the first time, thus paving the way towards exploring the exotic properties of the topological nodal-line fermions in condensed matter systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The discovery of the time-reversal invariant topological insulator has stimulated an enormous research interest in novel topological states protected by different symmetries1,2,3. One of the key properties of topological materials is the existence of symmetry-protected metallic edge or surface modes in bulk-insulating ground states, which is due to a topologically nontrivial ordering of bulk wave functions. Recently, because of the experimental observations of Weyl semimetals4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14, the research interest in topological phenomena in condensed matter systems has partially shifted from insulating materials to semimetals and metals. A Weyl semimetal is a topological state of matter whose low-energy bulk electrons are linearly dispersing Weyl fermions. The twofold degenerate Weyl nodes, carrying non-zero chiral charge, are connected on the boundary by Fermi arc surface states, which are predicted to exhibit unusual transport behaviours such as negative magnetoresistance and non-local transport current15,16,17,18. In contrast to Weyl semimetals whose bulk Fermi surface has dimension zero, nodal-line semimetals have extended band touching along one-dimensional curves in k space, presenting a significant expansion of topological materials beyond topological insulators and Weyl semimetals, and new opportunities to explore exotic topological nodal physics. Line-like touchings of a conduction and valence band need extra symmetries besides translation, such as mirror reflection, to be topologically protected. Kinematically, this protection involves a finite fraction of Brillouin zone. For this reason, this leads potentially to many anomalies in electromagnetic and transport response19,20,21,22. Similar to the case of Weyl nodes, one can define an integer topological invariant for the line node along which two nondegenerate bands touch19. Despite the many theoretical discussions of nodal-line semimetals, a material realization of topological nodal-line fermions has been lacking for many years, just like Weyl semimetals.

In this work we performed systematic theoretical study and experimental characterization of the electronic structure of a spin-orbit metal PbTaSe2, indicating the existence of topological nodal-line phase in this compound for the first time. The crystal lattice of this material lacks space inversion symmetry, which lifts the spin degeneracy of its electronic bulk bands. Our angle-resolved photoemission (ARPES) measurements together with density functional theory (DFT) calculations show that the conduction band originated from Pb-6p orbitals and the valence band from Ta-5d orbitals cross each other, forming three nodal-line states close to the Fermi energy. The nodal lines are protected by a reflection symmetry of the space group. The topological nodal-line state in PbTaSe2 belongs to the symmetry class A+R (p=2) of symmetry-protected semimetals19. We also demonstrate through effective Hamiltonian modelling and DFT simulations that the nodal lines are accompanied by surface bands. These surface states are due to the π Berry phase agglomerated around the nodal line in analogy to the states on the graphene zigzag edge. Our detailed theoretical modelling and calculation, aided by a systematic experimental characterization, establish the existence of topological nodal-line fermions in the superconducting compound PbTaSe2, opening the door for exploring the exotic properties of nodal-line states in condensed matter.

Results

Crystal and electronic structure

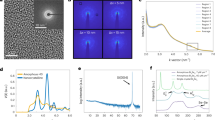

Our PbTaSe2 single crystals were prepared by the chemical vapour transport method, see Fig. 1a. The samples were of high structural quality, which was confirmed by our X-ray diffraction and scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM) measurements. The X-ray diffraction peaks shown in Fig. 1b are consistent with the space group of PbTaSe2,  (187), therefore demonstrating the lack of inversion symmetry of our PbTaSe2 single crystals. This is crucially important for lifting the spin degeneracy, a necessary condition for the formation of topological nodal lines. To further check the chemical composition of our samples, we performed a photoemission core-level scan. Clear Pb-5d, Ta-4f and Se-3d core-level peaks were observed in the photoemission spectrum, which confirms the correct chemical composition in our PbTaSe2 single-crystal samples, shown in Fig. 1c. To verify the superconducting property of our samples, a transport measurement was carried out. The measured resistivity curve (Fig. 1d) shows a clear superconducting transition temperature at 3.8 K, consistent with the value reported in ref. 23. Figure 1e,f shows STM images of the cleaved (001) surface. The topography image clearly reveals a hexagonal lattice with few defects, demonstrating the high quality of our samples. Furthermore, no surface reconstruction was observed on the cleaved surface. The high-resolution STM topography yields a lattice constant of 3.2 Å.

(187), therefore demonstrating the lack of inversion symmetry of our PbTaSe2 single crystals. This is crucially important for lifting the spin degeneracy, a necessary condition for the formation of topological nodal lines. To further check the chemical composition of our samples, we performed a photoemission core-level scan. Clear Pb-5d, Ta-4f and Se-3d core-level peaks were observed in the photoemission spectrum, which confirms the correct chemical composition in our PbTaSe2 single-crystal samples, shown in Fig. 1c. To verify the superconducting property of our samples, a transport measurement was carried out. The measured resistivity curve (Fig. 1d) shows a clear superconducting transition temperature at 3.8 K, consistent with the value reported in ref. 23. Figure 1e,f shows STM images of the cleaved (001) surface. The topography image clearly reveals a hexagonal lattice with few defects, demonstrating the high quality of our samples. Furthermore, no surface reconstruction was observed on the cleaved surface. The high-resolution STM topography yields a lattice constant of 3.2 Å.

(a) Optical image of PbTaSe2 single crystals measured in this work. (b) X-ray diffraction measurements showing the lattice parameters matching with the space group (187)  . (c) ARPES core-level spectrum showing clear Pb-5d, Se-3d and Ta-4f core-level peaks. (d) Resistivity as a function of temperature showing a superconducting transition at 3.8 K. (e,f) STM topography of PbTaSe2, indicative of a surface lattice constant 3.2 Å.

. (c) ARPES core-level spectrum showing clear Pb-5d, Se-3d and Ta-4f core-level peaks. (d) Resistivity as a function of temperature showing a superconducting transition at 3.8 K. (e,f) STM topography of PbTaSe2, indicative of a surface lattice constant 3.2 Å.

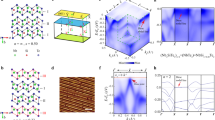

PbTaSe2 crystalizes in a hexagonal lattice system in which the unit cell consists of one Pb, one Ta and two Se atoms, and each atom resides on a hexagonal flat layer, shown in Fig. 2a. The stacking sequence of these atomic planes within the unit cell is Pb-Se-Ta-Se: A-A-B-A (A, B and C, here refer to the three high-symmetry spots on a hexagonal lattice). The lattice can also be viewed as a Pb layer intercalating two adjacent TaSe2 layers with Pb atoms sitting above Se atoms. The Pb intercalation suppresses the softening of phonon modes associated with the charge density wave in TaSe2 and stabilizes the hexagonal lattice on the surface24. This particular stacking does not preserve the space inversion symmetry; however, the lattice is reflection-symmetric with respect to the Ta atomic plane. In other words, the Ta atomic planes are a mirror plane of the crystal lattice under the mirror operation Rz that sends z to −z. This reflection symmetry of the lattice provides a protection for the topological nodal lines, as discussed later on. The bulk and (001)-projected surface Brillouin zones are shown in Fig. 2b. The A, H and L points are high-symmetry points on the kz=π plane, which is a mirror plane of the bulk Brillouin zone. Figure 2c presents an overview of the band structure calculation for PbTaSe2, which was performed by the method of generalized gradient approximation. Close to the Fermi level, two prominent features in the band structure are observed. One is a giant hole pocket around Γ, whose states are mainly derived from the Ta  orbitals that are oriented out of the Ta atomic plane, taking the Ta plane as the x–y plane. The second major contribution to the density of states at the Fermi level comes from the four bands that cross each other near H. The two electron-like conduction bands originate from Pb-6px/py orbitals and the two hole-like valence bands from

orbitals that are oriented out of the Ta atomic plane, taking the Ta plane as the x–y plane. The second major contribution to the density of states at the Fermi level comes from the four bands that cross each other near H. The two electron-like conduction bands originate from Pb-6px/py orbitals and the two hole-like valence bands from  orbitals. We note that all these orbitals are invariant under Rz. A zoom-in view of the bands around H without/with spin-orbit coupling (SOC) is shown in Fig. 2d,e, respectively. Without the inclusion of SOC, the conduction and valence bands become spin-degenerate. The two bands belong to different representations of the space group (the representation of the electron-like band is A′ and that of the hole-like band is A′′); therefore, the intersection of the two bands is protected by the crystalline symmetry, forming a spinless nodal ring. Once SOC is turned on, each band split into two spin branches with opposite spin orientations and mirror reflection eigenvalues as indicated in Fig. 2e. Only the crossings of branches with opposite mirror reflection eigenvalues remain gapless as a result of symmetry protection, forming a pair of nodal rings. Interestingly, SOC also gives rise to a third nodal ring on kz=0 plane. The detailed band dispersion and the rise of three nodal rings are very well captured by our effective k·p Hamiltonian (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Before proceeding to a detailed discussion of the nodal-line states, we will present the results of our ARPES measurement, verifying the overall band dispersion of Pb conduction bands and Ta valence bands obtained from our DFT calculation.

orbitals. We note that all these orbitals are invariant under Rz. A zoom-in view of the bands around H without/with spin-orbit coupling (SOC) is shown in Fig. 2d,e, respectively. Without the inclusion of SOC, the conduction and valence bands become spin-degenerate. The two bands belong to different representations of the space group (the representation of the electron-like band is A′ and that of the hole-like band is A′′); therefore, the intersection of the two bands is protected by the crystalline symmetry, forming a spinless nodal ring. Once SOC is turned on, each band split into two spin branches with opposite spin orientations and mirror reflection eigenvalues as indicated in Fig. 2e. Only the crossings of branches with opposite mirror reflection eigenvalues remain gapless as a result of symmetry protection, forming a pair of nodal rings. Interestingly, SOC also gives rise to a third nodal ring on kz=0 plane. The detailed band dispersion and the rise of three nodal rings are very well captured by our effective k·p Hamiltonian (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Before proceeding to a detailed discussion of the nodal-line states, we will present the results of our ARPES measurement, verifying the overall band dispersion of Pb conduction bands and Ta valence bands obtained from our DFT calculation.

(a) Hexagonal lattice of PbTaSe2. (b) Bulk band structure of PbTaSe2. (c) Calculated bulk band structure of PbTaSe2. (d,e) Zoom-in band structure around H without/with the inclusion of SOC. The colour code (red and blue) shows the orbital components. The up and down arrows indicate spin up and spin down along the z axis, respectively. (f,g) Same as d,e but for band structure around K. The bands in e,g correspond to those in the red rectangular boxes in c.

ARPES and DFT results of PbTaSe2

Figure 3a shows a brief overview of our ARPES band mapping, and the corresponding numerical calculation of the PbTaSe2 band structure is presented in Fig. 3b. The projected bulk bands and surface bands (as highlighted by white lines) were calculated for the Pb-terminated (001) surface. The DFT band structure reproduces the ARPES spectrum very well. Specifically, in the ARPES spectral cut, a band marked as SS1 with high intensity poke the Fermi level between  and

and  . This is the surface band associated with the Pb-terminated (001) surface and it corresponds to Dirac surface mode arising from a continuous bulk band gap opened by SOC23,24. Around

. This is the surface band associated with the Pb-terminated (001) surface and it corresponds to Dirac surface mode arising from a continuous bulk band gap opened by SOC23,24. Around  there are three concave bands whose binding energies at

there are three concave bands whose binding energies at  are 0.21, 0.75 and 0.80 eV. The top and bottom bands correspond to the electron-like bands derived from Pb-6p orbitals. The middle band, marked as SS2, is consistent with the surface band as plotted in Fig. 3b. The two bands at

are 0.21, 0.75 and 0.80 eV. The top and bottom bands correspond to the electron-like bands derived from Pb-6p orbitals. The middle band, marked as SS2, is consistent with the surface band as plotted in Fig. 3b. The two bands at  are tails of the two Ta-5d bands that cross the two Pb-6p bands forming the nodal rings in the vicinity of

are tails of the two Ta-5d bands that cross the two Pb-6p bands forming the nodal rings in the vicinity of  . Two Ta-5d bands have to degenerate in energy at

. Two Ta-5d bands have to degenerate in energy at  according to the Kramers theorem. The ARPES measured (001) Fermi surface with the incident photon energy of 64 eV, and the theoretical simulations are shown in Fig. 3c,d. At the Fermi level, our data show that the Fermi surface consists of three parts: a hexagon-shaped pocket centred at

according to the Kramers theorem. The ARPES measured (001) Fermi surface with the incident photon energy of 64 eV, and the theoretical simulations are shown in Fig. 3c,d. At the Fermi level, our data show that the Fermi surface consists of three parts: a hexagon-shaped pocket centred at  with smeared intensity inside, a dog-bone-shaped contour centred at the

with smeared intensity inside, a dog-bone-shaped contour centred at the  point and several circles surrounding the

point and several circles surrounding the  point. Our ARPES data and calculation show an agreement on those features. Furthermore, the hexagon centred at

point. Our ARPES data and calculation show an agreement on those features. Furthermore, the hexagon centred at  and the intensity inside are the surface band and the bulk hole pocket at

and the intensity inside are the surface band and the bulk hole pocket at  , respectively. The dog-bone-shaped contour corresponds to the one branch of the Ta valence band and the circles around

, respectively. The dog-bone-shaped contour corresponds to the one branch of the Ta valence band and the circles around  are from the other branch of the Ta valence band; the surface states and the spin-split conduction band are derived from Pb orbitals. As the binding energy decreases, we find that the Pb pockets at

are from the other branch of the Ta valence band; the surface states and the spin-split conduction band are derived from Pb orbitals. As the binding energy decreases, we find that the Pb pockets at  shrink while the Ta pockets expand outwards, which is in good accordance with the characteristics of the electron-like Pb bands and hole-like Ta bands.

shrink while the Ta pockets expand outwards, which is in good accordance with the characteristics of the electron-like Pb bands and hole-like Ta bands.

(a) ARPES spectra taken along  −

− −

− with 64-eV photons. (b) DFT-projected bulk bands and surface bands (bright white lines) of (001) surface with Pb termination. (c) ARPES isoenergy concours taken with 64-eV photons. (d) DFT Fermi surface contour of PbTaSe2 (001) surface. The yellow lines indicate the surface states on Pb-terminated (001) surface.

with 64-eV photons. (b) DFT-projected bulk bands and surface bands (bright white lines) of (001) surface with Pb termination. (c) ARPES isoenergy concours taken with 64-eV photons. (d) DFT Fermi surface contour of PbTaSe2 (001) surface. The yellow lines indicate the surface states on Pb-terminated (001) surface.

TaSe2 can be regarded as a building block of PbTaSe2, and therefore its electronic structure can be traced from that of PbTaSe2. To highlight the difference between electronic structures of TaSe2 and PbTaSe2, we mapped out the Fermi surface and band structure along  −

− −

− of the two compounds, shown in Fig. 4a,b. In the Fermi surface mapping of TaSe2, there are one dog-bone-shaped contour centred at

of the two compounds, shown in Fig. 4a,b. In the Fermi surface mapping of TaSe2, there are one dog-bone-shaped contour centred at  and only one circle-shaped contour centred at

and only one circle-shaped contour centred at  . Those contours are from Ta valence bands, and are consistent with previous work25. By contrast, the Fermi surface of PbTaSe2 has more ring-shaped contours centred at

. Those contours are from Ta valence bands, and are consistent with previous work25. By contrast, the Fermi surface of PbTaSe2 has more ring-shaped contours centred at  , signifying the contribution from the Pb layers. It is easier to view this difference from the

, signifying the contribution from the Pb layers. It is easier to view this difference from the  −

− −

− cut. TaSe2 does not show any electron-like bands at

cut. TaSe2 does not show any electron-like bands at  that exist in PbTaSe2. Figure 4c shows the ARPES mapping of the Pb and Ta bands of PbTaSe2 with photon energies from 54 to 70 eV. The middle band at

that exist in PbTaSe2. Figure 4c shows the ARPES mapping of the Pb and Ta bands of PbTaSe2 with photon energies from 54 to 70 eV. The middle band at  does not show any photon-energy dependence, which is consistent with the surface nature of this band. However, the other bands at

does not show any photon-energy dependence, which is consistent with the surface nature of this band. However, the other bands at  and

and  do not exhibit obvious changes with different photon energies either. This seems to contradict to the assignment of those bands as bulk bands according to our DFT calculations. The inconsistency can be understood by considering the fact that the Pb-6px/py and

do not exhibit obvious changes with different photon energies either. This seems to contradict to the assignment of those bands as bulk bands according to our DFT calculations. The inconsistency can be understood by considering the fact that the Pb-6px/py and  orbitals that constitute those bands are primarily confined within the Pb and Ta atomic planes (which are parallel to the x–y plane), and, thus, the interlayer couplings (say, the coupling of one Pb-6px/py orbital with another orbital on the adjacent Pb plane) is largely suppressed, which results in little kz/photon-energy dependence. In addition, we mapped out the ARPES spectrum of PbTaSe2 along

orbitals that constitute those bands are primarily confined within the Pb and Ta atomic planes (which are parallel to the x–y plane), and, thus, the interlayer couplings (say, the coupling of one Pb-6px/py orbital with another orbital on the adjacent Pb plane) is largely suppressed, which results in little kz/photon-energy dependence. In addition, we mapped out the ARPES spectrum of PbTaSe2 along  −

− with photon energy from 105 to 135 eV, shown in Fig. 4d. We observed that the intensity from the hole-like bulk pocket around Γ varied prominently with photon energy. It can be attributed to the fact that the states on the hole pocket are mainly derived from the Ta

with photon energy from 105 to 135 eV, shown in Fig. 4d. We observed that the intensity from the hole-like bulk pocket around Γ varied prominently with photon energy. It can be attributed to the fact that the states on the hole pocket are mainly derived from the Ta  orbitals that are oriented out of the Ta atomic plane and, thus, exhibit strong dispersion along the kz direction. By contrast, the band marked as SS1 did not show any photon-energy dependence, indicative of the surface nature of this band. We note that both our theoretical calculation and our ARPES measurement unambiguously indicate the existence of the electron-like Pb-6p bands around

orbitals that are oriented out of the Ta atomic plane and, thus, exhibit strong dispersion along the kz direction. By contrast, the band marked as SS1 did not show any photon-energy dependence, indicative of the surface nature of this band. We note that both our theoretical calculation and our ARPES measurement unambiguously indicate the existence of the electron-like Pb-6p bands around  , which inevitably cross the hole-like Ta-5d bands with a similar energy, leading to the formation of the nodal rings. The remarkable consistency between ARPES result and the our first-principles calculation lay a solid foundation for our theoretical investigation of the topological nodal lines in PbTaSe2.

, which inevitably cross the hole-like Ta-5d bands with a similar energy, leading to the formation of the nodal rings. The remarkable consistency between ARPES result and the our first-principles calculation lay a solid foundation for our theoretical investigation of the topological nodal lines in PbTaSe2.

Nodal lines and drumhead surface states of PbTaSe2

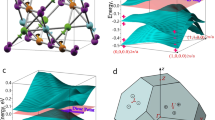

From the discussion before, we know that the electron-like bands from the intercalated Pb layers are the essential components for forming the topological-nodal-ring band structure. By comparing with the TaSe2 spectrum, our ARPES established unambiguously the existence of the Pb bands. To further examine the topological nodal-line states and associated surface states, we calculated the band structure for Pb- and Se-terminated surfaces as shown in Fig. 5a–d. The projected bulk band on each cut from  shows three nodal points at 0.05, 0.15 and 0.03 eV above the Fermi level. The first two closer to

shows three nodal points at 0.05, 0.15 and 0.03 eV above the Fermi level. The first two closer to  lie on the kz=π plane, while the third one is on the kz=0 plane. Let us refer to these three nodal lines as NL1, NL2 and NL3. Corresponding nodal points can be found on a cut of arbitrary orientation that includes

lie on the kz=π plane, while the third one is on the kz=0 plane. Let us refer to these three nodal lines as NL1, NL2 and NL3. Corresponding nodal points can be found on a cut of arbitrary orientation that includes  . For example, the band structure along a generic direction

. For example, the band structure along a generic direction  −

− is shown in Fig. 5b,d. Unlike the projected bulk band, which is independent of surface termination, the dispersion of surface bands is found to be sensitive to the surface condition. However, in both cases we do find a surface band connecting to each nodal line, indicative of the topological nature of the bulk nodal lines. In the Pb-termination case, the surface bands disperse outwards with respect to

is shown in Fig. 5b,d. Unlike the projected bulk band, which is independent of surface termination, the dispersion of surface bands is found to be sensitive to the surface condition. However, in both cases we do find a surface band connecting to each nodal line, indicative of the topological nature of the bulk nodal lines. In the Pb-termination case, the surface bands disperse outwards with respect to  , from NL1. The surface band connecting to NL2 grazes inwards at the edge of the lower bulk Dirac cone and merge into the bulk band. The surface band from NL3 disperses inwards with respect to

, from NL1. The surface band connecting to NL2 grazes inwards at the edge of the lower bulk Dirac cone and merge into the bulk band. The surface band from NL3 disperses inwards with respect to  , consistent with the SS2 band in our ARPES spectrum in Fig. 3, which forms a drumhead surface state contour. By contrast, on the Se-terminated surface the surface band connecting to NL2 first moves into the bulk band gap and then fall into the bulk band region. The surface band from NL1 disperses outwards and connects to NL3. Please refer to Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Note 2 for a detailed visualization of connection of the surface bands to the bulk nodal lines. To get an overall view of the nodal ring and surface band, we plot in Fig. 5e,f the isoenergy contour in the vicinity of the NL1 nodal ring of the Pb-terminated surface and the NL2 nodal ring of the Se-terminated surface, as indicated by the red dashed lines in Fig. 5a–d. Indeed, gapless nodal points and surface states can be found at every in-plane angle departing from

, consistent with the SS2 band in our ARPES spectrum in Fig. 3, which forms a drumhead surface state contour. By contrast, on the Se-terminated surface the surface band connecting to NL2 first moves into the bulk band gap and then fall into the bulk band region. The surface band from NL1 disperses outwards and connects to NL3. Please refer to Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Note 2 for a detailed visualization of connection of the surface bands to the bulk nodal lines. To get an overall view of the nodal ring and surface band, we plot in Fig. 5e,f the isoenergy contour in the vicinity of the NL1 nodal ring of the Pb-terminated surface and the NL2 nodal ring of the Se-terminated surface, as indicated by the red dashed lines in Fig. 5a–d. Indeed, gapless nodal points and surface states can be found at every in-plane angle departing from  . These nodal rings are protected against gap opening by the crystalline symmetry. Specifically, the states in the two Pb branches belong to two different representations of the space group, namely S3 and S4 as shown in Fig. 5g. The same is true for the two Se branches. In particular, with respect to the Ta atomic plane, the two representations have opposite mirror eigenvalues under the reflection operation. Therefore, gap opening is forbidden at the crossing point between two branches of different mirror eigenvalues, which results in the nodal rings discussed in this work. In this sense, the nodal rings are under the protection of the reflection symmetry. If we shift the Pb atom slightly in the vertical direction, thus breaking the reflection symmetry, all of the four branches are found to belong to the same S2 representation of the reduced space group and, in this case, a gap opening is allowed at every crossing point of these branches as illustrated in Fig. 5h. A similar gap opening is also found in NL3 on kz=0 plane on breaking the reflection symmetry, please see Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Note 3.

. These nodal rings are protected against gap opening by the crystalline symmetry. Specifically, the states in the two Pb branches belong to two different representations of the space group, namely S3 and S4 as shown in Fig. 5g. The same is true for the two Se branches. In particular, with respect to the Ta atomic plane, the two representations have opposite mirror eigenvalues under the reflection operation. Therefore, gap opening is forbidden at the crossing point between two branches of different mirror eigenvalues, which results in the nodal rings discussed in this work. In this sense, the nodal rings are under the protection of the reflection symmetry. If we shift the Pb atom slightly in the vertical direction, thus breaking the reflection symmetry, all of the four branches are found to belong to the same S2 representation of the reduced space group and, in this case, a gap opening is allowed at every crossing point of these branches as illustrated in Fig. 5h. A similar gap opening is also found in NL3 on kz=0 plane on breaking the reflection symmetry, please see Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Note 3.

(a,b) DFT project bulk bands and surface bands (bright white lines) of Pb-terminated (001) surface along  −

− −

− and a generic direction

and a generic direction  −

− , respectively. (c,d) Same as a,b but of Se-terminated (001) surface. (e,f) The isoenergy contour showing the nodal-line states (NL) and surface states (SS). The energy is 0.10 and 0.15 eV above the Fermi level for Pb- and Se termination, respectively, as indicated by the red dashed lines in a–d. (g,h) Bulk band structure of PbTaSe2 with and without the reflection symmetry, respectively. In h, the reflection symmetry is broken by moving the Pb atom slightly in the vertical direction. (i) Schematic of the closed contours encircling the nodal lines for the calculation of the winding number. The arrows indicate the direction on the loops along which the Berry’s connection is integrated. (j) Schematic of a spectral cut passing

, respectively. (c,d) Same as a,b but of Se-terminated (001) surface. (e,f) The isoenergy contour showing the nodal-line states (NL) and surface states (SS). The energy is 0.10 and 0.15 eV above the Fermi level for Pb- and Se termination, respectively, as indicated by the red dashed lines in a–d. (g,h) Bulk band structure of PbTaSe2 with and without the reflection symmetry, respectively. In h, the reflection symmetry is broken by moving the Pb atom slightly in the vertical direction. (i) Schematic of the closed contours encircling the nodal lines for the calculation of the winding number. The arrows indicate the direction on the loops along which the Berry’s connection is integrated. (j) Schematic of a spectral cut passing  . The grey shaded region indicates the projected bulk band associated with a single nodal ring encircling

. The grey shaded region indicates the projected bulk band associated with a single nodal ring encircling  , and the red curves depict the surface states (SS).

, and the red curves depict the surface states (SS).

Discussion

Let us briefly discuss the topological characterization of the nodal lines and the origin of the surface bands. The material PbTaSe2 is time-reversal-symmetric, with time-reversal symmetry represented by  , where

, where  denotes complex conjugation and σ2 is the second Pauli matrix acting on the electron spin. The mirror symmetry Rz acts in spin space as iσ3 and therefore commutes with

denotes complex conjugation and σ2 is the second Pauli matrix acting on the electron spin. The mirror symmetry Rz acts in spin space as iσ3 and therefore commutes with  . This would place PbTaSe2 in class AII in the classification of ref. 19. However, since the nodal lines are centred around momenta H/H′ and K/K′, which are not invariant under time-reversal, but pairwise map into each other, the time-reversal symmetry imposes no constraints on the nodal lines individually. The material has, therefore, to be classified according to the time-reversal breaking class A-R, which admits an integer topological classification for Fermi surfaces of codimension 2, that is, lines (p=2 in ref. 19). The nodal lines carry a topological quantum number n+, which is given by the difference in the number of occupied bands with Rz eigenvalue +i inside and outside the line. In the case at hand, n+=−1 for the nodal line (NL3) in the kz=0 plane, while n+=+1 (NL1) and n+=−1 (NL2) for the two nodal lines in the kz=π plane. We have also computed numerically under the DFT framework the winding number

. This would place PbTaSe2 in class AII in the classification of ref. 19. However, since the nodal lines are centred around momenta H/H′ and K/K′, which are not invariant under time-reversal, but pairwise map into each other, the time-reversal symmetry imposes no constraints on the nodal lines individually. The material has, therefore, to be classified according to the time-reversal breaking class A-R, which admits an integer topological classification for Fermi surfaces of codimension 2, that is, lines (p=2 in ref. 19). The nodal lines carry a topological quantum number n+, which is given by the difference in the number of occupied bands with Rz eigenvalue +i inside and outside the line. In the case at hand, n+=−1 for the nodal line (NL3) in the kz=0 plane, while n+=+1 (NL1) and n+=−1 (NL2) for the two nodal lines in the kz=π plane. We have also computed numerically under the DFT framework the winding number  , where A(k)=i∑a〈ua,k|∇ ua,k〉 is the Berry connection of the occupied Bloch bands |ua,k〉. For a closed loop encircling any of the nodal lines, we find that γ=±π, indicating the topological protection of the nodal line as shown in Fig. 5i.

, where A(k)=i∑a〈ua,k|∇ ua,k〉 is the Berry connection of the occupied Bloch bands |ua,k〉. For a closed loop encircling any of the nodal lines, we find that γ=±π, indicating the topological protection of the nodal line as shown in Fig. 5i.

The topological origin of the observed surface states is rather subtle. Surface states associated with the topological invariant n+ via the bulk-boundary correspondence should only appear on surfaces that preserve Rz. The (001) surface, however, breaks Rz. The reason why we still observe surface states can be understood from the Berry phase of π around the nodal line and the analogy to the edge states on the zigzag edge of graphene. Consider the bulk Hamiltonian on a plane in momentum space that contains both K and H. At low energies, each nodal ring pierces this plane twice, giving rise to two Dirac cones in this Hamiltonian. These two cones have a Berry phase +π and −π with respect to the orientation of the plane, precisely as in (spinless) graphene, as schematically depicted in Fig. 5j. We know that for any termination of a graphene sample, an edge state emanates from the projection of each of the Dirac points in the edge Brillouin zone (except for the pathological case where both Dirac points project on the same spot in the edge Brillouin zone). By this analogy, we also expect these edge states to emanate from the surface projections of the nodal lines in any direction away from the  point, thereby forming a surface band. We note that the dispersion of this band and even whether it appears inside or outside the projection of the nodal line is not universal and depends on the details of the surface termination.

point, thereby forming a surface band. We note that the dispersion of this band and even whether it appears inside or outside the projection of the nodal line is not universal and depends on the details of the surface termination.

Recently, some preprint theoretical lines of work have reported on Ca3P2 and Cu3PdN, proposing that there may be nodal-line states26,27,28. We note that our work is distinct from those lines of work in many ways. Both Ca3P2 and Cu3PdN are centrosymmetric and, therefore, because of the coexistence of time-reversal and inversion symmetry, have fourfold degeneracy at the nodal ring. By contrast, the degeneracy of nodal-ring states is two in PbTaSe2 because of the lack of inversion symmetry. In Ca3P2 and Cu3PdN, the nodal-line states exist only in the absence of SOC. In real materials SOC, however, always exists. In PbTaSe2, SOC is an essential ingredient for the formation of nodal-ring states. Our ARPES measurement established an experimental characterization of the topological nodal-line material PbTaSe2.

In summary, our direct experimental observation by ARPES of the coexistence of Pb concave bands and Ta convex bands centred at  in the non-centrosymmetric superconductor PbTaSe2 is in good agreement with our first-principles band structure calculations, establishing the realization of the unusual ring-shaped topological nodal-line states in this compound. The topological nodal rings are protected by the reflection symmetry of the system. Meanwhile, the nodal rings are uniquely associated with drumhead-like surface states in a manner that resembles the connections of edge states and the nodal points in graphene. Considering the one-dimensional nodal characteristics of the bulk band and the two-dimensional topological ‘drumhead’ surface states, topological nodal-line semimetals stand as a distinct class of topological materials beyond Weyl semimetals and topological insulators. For example, nodal-line states possess an extra degree of freedom for manipulating novel properties of Weyl materials, which is the finite size of the nodal line. Furthermore, interaction-induced instabilities that have been broadly discussed for Weyl semimetals should be more likely occurring in nodal-line states because of the higher density of states at the Fermi energy. In addition, superconductivity is induced by intercalating Pb layers to TaSe2, which also offers the essential ingredient, the Pb-conducting orbitals, for the formation of the topological nodal-line states. Considering the intrinsic superconductivity, the spin-split bulk nodal-line band structure and the nontrivial surface states close to the Fermi level, it is possible that helical superconductivity and p-wave Cooper pairing may exist in this compound without the aid of the proximity effect29,30. Therefore, novel physics may arise from the interplay of the nodal-line states and the emergent superconductivity of PbTaSe2, which calls for further experimental investigation on PbTaSe2. Our ARPES measurements, detailed DFT simulation and theoretical analysis demonstrate the fundamental mechanism for realizing topological nodal-line fermions in PbTaSe2, and pave the way for exploring the exotic properties of topological nodal-line states in condensed matter systems.

in the non-centrosymmetric superconductor PbTaSe2 is in good agreement with our first-principles band structure calculations, establishing the realization of the unusual ring-shaped topological nodal-line states in this compound. The topological nodal rings are protected by the reflection symmetry of the system. Meanwhile, the nodal rings are uniquely associated with drumhead-like surface states in a manner that resembles the connections of edge states and the nodal points in graphene. Considering the one-dimensional nodal characteristics of the bulk band and the two-dimensional topological ‘drumhead’ surface states, topological nodal-line semimetals stand as a distinct class of topological materials beyond Weyl semimetals and topological insulators. For example, nodal-line states possess an extra degree of freedom for manipulating novel properties of Weyl materials, which is the finite size of the nodal line. Furthermore, interaction-induced instabilities that have been broadly discussed for Weyl semimetals should be more likely occurring in nodal-line states because of the higher density of states at the Fermi energy. In addition, superconductivity is induced by intercalating Pb layers to TaSe2, which also offers the essential ingredient, the Pb-conducting orbitals, for the formation of the topological nodal-line states. Considering the intrinsic superconductivity, the spin-split bulk nodal-line band structure and the nontrivial surface states close to the Fermi level, it is possible that helical superconductivity and p-wave Cooper pairing may exist in this compound without the aid of the proximity effect29,30. Therefore, novel physics may arise from the interplay of the nodal-line states and the emergent superconductivity of PbTaSe2, which calls for further experimental investigation on PbTaSe2. Our ARPES measurements, detailed DFT simulation and theoretical analysis demonstrate the fundamental mechanism for realizing topological nodal-line fermions in PbTaSe2, and pave the way for exploring the exotic properties of topological nodal-line states in condensed matter systems.

Methods

Sample growth method

Single crystals of PbTaSe2 were grown with the chemical vapor transport (CVT) method using chlorine in the form of PbCl2 as a transport agent. For the pure synthesis of PbTaSe2, stoichiometric amounts of the elements (purity of Pb and Ta: 6N, of Se: 5N) were loaded into a quartz ampoule, which was evacuated, sealed and fed into a furnace (850 °C) for 5 days. About 10 g of the prereacted PbTaSe2 were placed together with a variable amount of PbCl2 (purity 5 N) at one end of another silica ampoule (length 30–35 cm, inner diameter 2.0 cm and outer diameter 2.5 mm). All treatments were carried out in an Argon box, with continuous purification of the Argon atmosphere resulting in an oxygen and water content of less than 1 p.p.m. Again, the ampoule was evacuated, sealed and fed into a furnace. The end of the ampoule containing the prereacted material was held at 850 °C, while the crystals grew at the other end of the ampoule at a temperature of 800 °C (corresponding to a temperature gradient of 2.5 K cm−1) during a time of typically 1 week. Compact single crystals of sizes of up to 8 × 5 × 5 mm3 were obtained.

ARPES and STM methods

ARPES measurements were performed at the liquid nitrogen temperature in the beamline I4 at the MAX-lab in Lund, Sweden. The energy and momentum resolution was better than 20 meV and 1% of the surface Brillouin zone for ARPES measurements at the beamline I4 at the MAX-lab. Samples were cleaved in situ under a vacuum condition better than 1 × 10−10 torr. Samples were found to be stable and without degradation for a typical measurement period of 24 h. STM experiments were conducted with a commercial system (Unisoku). Samples were cleaved at room temperature in a vucuum better than 2 × 10−10 mbar and were transferred to a STM head precooled to 77 K. Constant-current mode STM images were taken with chemical-etched Pt/Ir tips. Bias voltages were applied to the samples.

Computational method

We computed electronic structures using the norm-conserving pseudopotentials as implemented in the OpenMX package within the generalized gradient approximation schemes31,32. Experimental lattice constants were used33. A 12 × 12 × 4 Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh was used in the computations. The SOC effects are included self-consistently34. For each Pb atom, three, three, three and two optimized radial functions were allocated for the s, p, d and f orbitals (s3p3d3f2), respectively, with a cutoff radius of 8 Bohr. For each Ta atom, d3p2d2f1 was adopted with a cutoff radius of 7 Bohr. For each Se atom, d3p2d2f1 was adopted with a cutoff radius of 7 Bohr. A regular mesh of 300 Ry in real space was used for the numerical integrations and for the solution of the Poisson equation. To calculate the surface electronic structures, we constructed first-principles tight-binding model Hamilton. The tight-binding model matrix elements are calculated by projecting onto the Wannier orbitals35. We use Pb p, Ta s and d, and Se p orbitals were constructed without performing the procedure for maximizing localization.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Bian, G. et al. Topological nodal-line fermions in spin-orbit metal PbTaSe2. Nat. Commun. 7:10556 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10556 (2016).

References

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010).

Qi, X.-L. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110 (2011).

Hasan, M. Z., Xu, S.-Y. & Neupane, M. Topological Insulators, Topological Dirac semimetals, Topological Crystalline Insulators, and Topological Kondo Insulators. in Topological Insulators, Fundamentals and Perspectives (eds Ortmann F., Roche S., Valenzuela S. O. John Wiley & Sons (2015).

Wan, X., Turner, A. M., Vishwanath, A. & Savrasov, S. Y. Topological Semimetal and Fermi-arc surface states in the electronic structure of pyrochlore iridates. Phys. Rev. B 83, 205101 (2011).

Burkov, A. A. & Balents, L. Weyl semimetal in a topological insulator multilayer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 127205 (2011).

Xu, G. et al. Chern semi-metal and quantized anomalous Hall effect in HgCr2Se4 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 186806 (2011).

Singh, B. et al. Topological electronic structure and Weyl semimetal in the TlBiSe2 class of semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 86, 115208 (2012).

Huang, S.-M. et al. An inversion breaking Weyl semimetal state in the TaAs material class. Nat. Commun. 6, 7373 (2015).

Weng, H., Fang, C., Fang, Z., Bernevig, A. & Dai, X. Weyl semimetal phase in non-centrosymmetric transition metal monophosphides. Phys. Rev. X 5, 011029 (2015).

Xu, S.-Y. et al. Discovery of a Weyl Fermion semimetal and topological Fermi arcs. Science 349, 613–617 (2015).

Lu, L. et al. Experimental observation of Weyl points. Science 349, 622–624 (2015).

Lv, B. Q. et al. Experimental discovery of Weyl semimetal TaAs. Phys. Rev. X 5, 031013 (2015).

Xu, S.-Y. et al. Observation of Fermi arc surface states in a topological metal. Science 347, 294–298 (2015).

Yang, B.-J. & Nagaosa, N. Classification of stable three-dimensional Dirac semimetals with nontrivial topology. Nat. Commun. 5, 4898 (2014).

Hosur, P. Friedel oscillations due to Fermi arcs in Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 86, 195102 (2012).

Son, D. T. & Spivak, B. Z. Chiral anomaly and classical negative magnetoresistance of Weyl metals. Phys. Rev. B 88, 104412 (2013).

Vazifeh, M. M. & Franz, M. Electromagnetic response of Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 027201 (2013).

Ojanen, T. Helical Fermi arcs and surface states in time-reversal invariant Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 87, 245112 (2013).

Chiu, C. & Schnyder, A. Classification of reflection symmetry protected topological semimetals and nodal superconductors. Phy. Rev. B 90, 205136 (2014).

Yang, S. A., Pan, H. & Zhang, F. Dirac and Weyl superconductors in three dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 046401 (2014).

Burkov, A. A., Hook, M. D. & Balents, L. Topological nodal semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 84, 235126 (2011).

Phillips, M. & Aji, V. Tunable line node semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 90, 115111 (2014).

Ali, M. N., Gibson, Q. D., Klimczuk, T. & Cava, R. J. Noncentrosymmetric superconductor with a bulk three-dimensional Dirac cone gapped by strong spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. B 89, 020505(R) (2014).

Chang, T.-R. et al. Topological dirac states and pairing correlations in the non-centrosymmetric superconductor PbTaSe2. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1511.06231 (2015).

Laverock, J. et al. k-resolved susceptibility function of 2H-TaSe2 from angle-resolved photoemission. Phys. Rev. B 88, 035108 (2013).

Xie, L. S. et al. Potential ring of Dirac nodes in a new polymorph of Ca3P2 . APL Mater. 3, 083602 (2015).

Yu, R., Weng, H., Fang, Z., Dai, X. & Hu, X. Topological node-line semimetal and dirac semimetal state in antiperovskite Cu3PdN. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 036807 (2015).

Kim, Y., Wieder, B. J., Kane, C. L. & Rappe, A. M. Dirac line nodes in inversion-symmetric crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 036806 (2015).

Fu, L. & Kane, C. L. Superconducting proximity effect and Majorana fermions at the surface of a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 096407 (2008).

Xu, S.-Y. et al. Momentum-space imaging of Cooper pairing in a half-Dirac-gas topological superconductor. Nat. Phys. 10, 943–950 (2014).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Ozaki, T. Variationally optimized atomic orbitals for largescale electronic structures. Phys. Rev. B 67, 155108 (2003).

Eppinga, R. & Wiegers, G. A. A generalized schene for niobium and tatalum dichalcogenides intercalated with pos-transition elements. Phys. B. C 99, 121–127 (1980).

Theurich, G. & Hill, N. A. Self-consistent treatment of spin-orbit coupling in solids using relativistic fully separable ab initio pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 64, 073106 (2001).

Weng, H., Ozaki, T. & Terakura, K. Revisiting magnetic coupling in transition-metal-benzene complexes with maximally localized Wannier functions. Phys. Rev. B 79, 235118 (2009).

Acknowledgements

Work at Princeton University and Princeton-led synchrotron-based ARPES measurements were supported by the US Department of Energy (DOE)/Basic Energy Sciences under DE-FG-02-05ER46200. We gratefully acknowledge C.M. Polley, J. Adell, M. Leandersson and T. Balasubramanian for their beamline assistance at the Max-lab. We also thank A.P. Schnyder, C. Fang and M. Franz for discussions. The work at the Northeastern University was supported by the USDOE, Office of Science BES grant number DE-FG02-07ER46352, and was benefited from Northeastern University’s Advanced Scientific Computation Center (ASCC) and the NERSC supercomputing centre through DOE grant number DE-AC02-05CH11231. S.J. acknowledges National Basic Research Program of China under Grant Nos 2013CB921901 and 2014CB239302. H.L. acknowledges the Singapore National Research Foundation for the support under NRF Award No. NRF-NRFF2013-03. F.C. acknowledges the support provided by the Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan under project number MOST-102-2119-M-002-004. R.S. and F.C. acknowledge the support provided by the Academia Sinica research programme on nanoscience and nanotechnology project number NM004. T.-R.C. and H.-T.J. were supported by the National Science Council, Taiwan. H.-T.J. also thanks the National Center for High-Performance Computing, Computer and Information Network Center National Taiwan University and National Center for Theoretical Sciences, Taiwan, for technical support. Sample characterization was supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundations-Emergent Phenomena in Quantum Systems Initiative through grant GBMF4547 (M.Z.H.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.B., S.-Y.X., H.Z. and I.B. performed the experiments with assistance from D.S.S., C.L., N.A., M.N. and M.Z.H.; R.S., F.C., Z.Y., C.Z. and S.J. provided samples; T.-R.C., G.B., H.-T.J., S.-M.H., G.C., B.W., C.-C.L., H.L. and A.B. carried out the first-principles calculations; T.N., C.-K.C., G.B. and M.Z.H. performed the theoretical modelling and analysis. M.Z.H. was responsible for the overall direction, planning and integration among different research units.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-3 and Supplementary Notes 1-3 (PDF 407 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Bian, G., Chang, TR., Sankar, R. et al. Topological nodal-line fermions in spin-orbit metal PbTaSe2. Nat Commun 7, 10556 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10556

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10556

This article is cited by

-

Comprehensive investigation of quantum oscillations in semimetal using an ac composite magnetoelectric technique with ultrahigh sensitivity

npj Quantum Materials (2024)

-

Experimental observation of multiple topological nodal structure in LaSb2

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2024)

-

Weyl nodal ring states and Landau quantization with very large magnetoresistance in square-net magnet EuGa4

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Node line semimetal states in tungsten-based materials

Tungsten (2023)

-

3D quantum Hall effect in a topological nodal-ring semimetal

Quantum Frontiers (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

−

− −

− of PbTaSe2 (top) and TaSe2 (bottom). (c) ARPES spectra of PbTaSe2 along

of PbTaSe2 (top) and TaSe2 (bottom). (c) ARPES spectra of PbTaSe2 along  −

− taken with different photon energies. (d) ARPES spectra along

taken with different photon energies. (d) ARPES spectra along  −

− taken with different photon energies.

taken with different photon energies.