Abstract

Revascularization of immature necrotic teeth is a reliable treatment alternative to conventional apexogenesis or apexification. In case 1, a 12-year-old boy had his necrotic, immature mandibular left second premolar treated with a revascularization technique. At a 24-month follow-up, periapical radiolucency had disappeared and thickening of the root wall was observed. In cases 2 and 3, a 10-year-old boy had his necrotic, immature, bilateral mandibular second premolars treated with the same modality. At 48-month (in case 2) and 42-month (in case 3) follow-ups, loss of periapical radiolucencies and increases in the root wall thickness were also observed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pulp necrosis of immature teeth may give rise to complications.1 It prevents further development of the root, leaving a tooth with thin root walls. Conventional root canal treatment techniques used in mature teeth are difficult to use in immature teeth which have various anatomical complexities.2 The instrumentation and obturation of immature root canals are difficult or impossible with conventional techniques.3 Furthermore, weak teeth with thin root walls are susceptible to fracture.

Conventional apexification uses calcium hydroxide as intracanal medicament to induce apical closure over time. This is a successful treatment technique for immature teeth, but it has several disadvantages, including the need for multiple visits over a relatively long period of time (an average of 12 months). In addition, the root canal may not be reinforced.4 An alternative to conventional apexification with calcium hydroxide is to make an artificial apical barrier to prevent the extrusion of root canal filling materials. The material of choice is mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) which has good sealing ability and biocompatibility.5 However, it does not also promote further root development.

Recently, an alternative biologically based treatment has been introduced for immature teeth with necrotic pulp.6 Procedures that preserve the remaining dental pulp stem cells and mesenchymal stem cells of the apical papilla can result in intracanal revascularization and continued root development.7 The revascularization of these teeth is based on the concept that vital stem cells in the apical papilla can survive pulpal necrosis, even in the presence of periapical infection, because the open apex provides good communication to the periapical tissues.8,9 The present case reports evaluated the long-term prognosis of revascularization in necrotic immature teeth, with the aim of providing reliable evidences for the revascularization technique.

Case reports

Case 1

A 12-year-old boy was referred to our department for treatment of his mandibular left second premolar. His medical history was unremarkable. When taking the dental history, the patient stated that prior to the first visit, he experienced severe pain, which had decreased over the past 5 days, but increased with chewing. Clinical examination revealed that the tooth was not responsive to electric pulp test and was sensitive to percussion. Periodontal probing depths were within normal limits (<3 mm). Radiographic examination revealed a immature tooth with periapical radiolucency (Figure 1a).

Periapical radiographs in case 1. (a) Pre-treatment periapical radiograph of the mandibular left second premolar. Note the periapical radiolucency and root immaturity (white arrows). (b) Periapical radiograph obtained immediately after placement of MTA into the root canal (white arrow). (c) Periapical radiograph obtained after gutta-percha (white arrow) obturation and composite resin restoration (black arrow). (d) Periapical radiograph obtained at the 6-week follow-up. Note the diminished periapical radiolucency (white arrow). (e) Periapical radiograph obtained at the 24-month follow-up. The root wall thickness has increased (white arrow) and apical closure is complete. MTA, mineral trioxide aggregate.

Based on the results of the clinical and radiographic examinations, a diagnosis was made of pulp necrosis with symptomatic apical periodontitis. Under local anesthesia, the tooth was isolated with a rubber dam and the access cavity was prepared. The root canal was irrigated with 10 mL of 3% sodium hypochlorite for 2 min, and then dried with sterile paper points. A creamy paste mixture of metronidazole (Samil Pharm, Seoul, Korea), ciprofloxacin (Sinil Pharm, Seoul, Korea) and cefaclor (Myungin Pharm, Seoul, Korea) in sterile saline was applied using a lentulo-spiral and tapped down into the canal with the blunt end of sterile paper points. The tooth was temporarily restored using Caviton (GC, Aichi, Japan).

The patient was asymptomatic 2 weeks later. The Caviton was removed under rubber dam isolation. The mixture of antibiotics was completely removed with 3% sodium hypochlorite and sterile saline. The apical tissue was stimulated with a No. 10 K-file to induce bleeding. A blood clot formed in the canal about 15 min after stimulation. MTA (Dentsply Tulsa Dental, Johnson City, TN, USA) was applied over the blood clot, followed by a moist cotton pellet (Figure 1b). Caviton was placed temporarily over the cotton pellet. Two weeks later, the Caviton was removed and the remainder of the root canal space was obturated using an Obtura-II (Obtura Corp., Fenton, MO, USA). A composite resin restoration (Z250; 3M ESPE, St Paul, MN, USA) was placed into the access cavity to create a tight coronal seal (Figure 1c).

When the patient came back for 6-week follow-up, the periapical radiolucency had diminished (Figure 1d). At the 24-month follow-up, a completely closed root apex was observed, and no periapical pathosis was seen (Figure 1e). Preoperative and 24-month follow-up radiographs were compared with ImageJ software (version 1.41; National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) and a TurboReg plug-in (Biomedical Imaging Group, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Lausanne, VD, Switzerland) to minimize any dimensional changes in the images due to angular differences in the x-ray central beam at the time of image acquisition.10,11 This revealed an increase in root length and root wall thickness.

Case 2

A 10-year-old boy was referred to our department for treatment of his mandibular left second premolar. According to the patient, he first felt moderate pain 7 days prior to presentation to our department. He then presented to a dental emergency center with sudden facial swelling and severe pain 1 day ago. His mandibular left second premolar was treated with a pulpotomy at the center. His medical history was unremarkable. Clinical examinations revealed a negative response to electric pulp test and sensitivity to percussion. In addition, buccal gingival swelling was observed. Periodontal probing depth was within normal limits (<3 mm) (Figure 2a and b). A periapical radiograph revealed an immature root with periapical radiolucency (Figure 2c). The patient stated that his pain and facial swelling had decreased following the pulpotomy treatment.

Intraoral photographs and periapical radiographs in case 2. (a) Pre-treatment occlusal photograph of the mandibular left second premolar. (b) Pre-treatment intraoral photograph of the tooth. Gingival swelling is evident on the buccal side (white arrow). (c) Pre-treatment periapical radiograph of the tooth. Periapical radiolucency with root immaturity is evident (white arrow). (d) Intraoral photograph obtained 2 weeks later. Buccal gingival swelling has disappeared (white arrow). (e) Periapical radiograph obtained immediately after placement of MTA into the root canal. (f) Periapical radiograph obtained after gutta-percha obturation and composite resin restoration. (g) Periapical radiograph obtained at the 2-month follow-up. Periapical radiolucency has decreased and the root wall has thickened (white arrow). (h) Periapical radiograph obtained at the 48-month follow-up. Thickening of the root wall is evident and periapical radiolucency has disappeared completely (white arrow). MTA, mineral trioxide aggregate.

The tooth was isolated with a rubber dam and the access cavity was prepared. The root canal was irrigated with 10 mL of 3% sodium hypochlorite for 2 min, and then dried with sterile paper points. A creamy paste mixture of metronidazole (Samil Pharm), ciprofloxacin (Sinil Pharm) and cefaclor (Myungin Pharm) in sterile saline was applied into the canal using a lentulo-spiral and tapped down into the canal with the blunt end of sterile paper points. The tooth was temporarily restored using Caviton.

The patient returned to our department 2 weeks later. His buccal gingival swelling had disappeared completely, and he did not feel any discomforts (Figure 2d). The Caviton was removed under rubber dam isolation. The antibiotic mixture was thoroughly removed with 3% sodium hypochlorite and sterile saline. The apical tissue was stimulated with a No. 10 K-file to induce bleeding. A blood clot formed in the canal about 15 min after stimulation. MTA was applied over the blood clot followed by a moist cotton pellet (Figure 2e). Caviton was placed temporarily over the cotton pellet. The patient was asymptomatic 2 weeks later. The Caviton was removed carefully under rubber dam isolation. The remainder of the root canal space was obturated using an Obura-II (Obtura Corp.), and a composite resin restoration (Z250; 3M ESPE) was placed into the access cavity (Figure 2f).

At the 2-month follow-up, the periapical radiograph revealed a decrease in the periapical radiolucency (Figure 2g). The patient exhibited no clinical discomforts. At the 48-month follow-up, the periapical radiolucency had disappeared completely (Figure 2h). Preoperative and 48-month follow-up radiograph were analyzed with same modality described for case 1 and confirmed an increase in root thickness.

Case 3

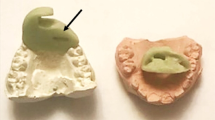

This case involved the same patient as case 2. At the 6-month follow-up of the revascularized mandibular left second premolar, slight gingival swelling was observed on the buccal surface of the mandibular right second premolar (Figure 3a). Clinical examinations revealed a sensitivity to percussion and negative response to electric pulp test. The periodontal probing depths were within normal limits (<3 mm). A periapical radiograph revealed an immature root with periapical radiolucency (Figure 3b).

Intraoral photographs and periapical radiographs in case 3. (a) Pre-treatment intraoral photograph of the mandibular right second premolar. Gingival swelling on the buccal side is evident (white arrow). (b) Pre-treatment periapical radiograph of the tooth. Note the periapical radiolucency with thin root walls (white arrow). (c) Intraoral photograph obtained after access cavity preparation. Note the bloody purulent discharge (white arrow). (d) Intraoral photograph obtained 1 week later. Complete reduction of gingival swelling is evident (white arrow). (e) Periapical radiograph obtained immediately after placement of MTA into the root canal. (f) Periapical radiograph obtained at the 2-month follow-up. Periapical radiolucency has decreased (white arrow). (g) Periapical radiograph obtained at the 42-month follow-up. Thickness of the root wall has increased and the periapical radiolucency has disappeared completely (white arrow). MTA, mineral trioxide aggregate.

The tooth was isolated with a rubber dam under local anesthesia. When the access cavity was prepared, bloody purulent discharge was evident (Figure 3c). The root canal was irrigated with 20 mL of 3% sodium hypochlorite for 5 min until the pus discharge ceased. No instrumentation was applied into the canal. The root canal was dried with sterile paper points. A creamy paste mixture of metronidazole (Samil Pharm), ciprofloxacin (Sinil Pharm) and cefaclor (Myungin Pharm) in sterile saline was applied into the canal using a lentulo-spiral and tapped down into the canal with the blunt end of sterile paper points. The tooth was temporarily restored using Caviton.

After 1 week, the gingival swelling disappeared completely (Figure 3d). The Caviton was removed under rubber dam isolation. The antibiotic mixture was flushed thoroughly with 3% sodium hypochlorite and sterile saline. The apical tissue was stimulated with a No. 10 K-file to induce bleeding in the canal space. A blood clot formed in the canal about 15 min after stimulation. MTA was applied over the blood clot, followed by a moist cotton pellet (Figure 3e). Caviton was placed temporarily over the cotton pellet. Two weeks later, the patient was asymptomatic. The Caviton was removed and the remainder of the root canal space was obturated using an Obura-II (Obtura Corp.). A composite resin restoration (Z250; 3M ESPE) was then placed into the access cavity.

At the 2-month follow-up, a periapical radiograph showed that the periapical radiolucency had decreased (Figure 3f). The patient exhibited no clinical discomfort. At the 42-month follow-up, the periapical radiolucency had disappeared completely (Figure 3g). The preoperative and 42-month follow-up radiographs were analyzed with same modality used in cases 1 and 2, which confirmed an increase in root thickness.

Discussion

Some reports have suggested that the revascularization technique is a reliable alternative treatment because it promotes the development of a longer and thicker root that is less susceptible to fracture.12,13,14 In the present case reports, the root walls and open apexes of necrotic immature teeth were thickened and closed after revascularization.

Various combinations of topical antibiotics may be used to disinfect necrotic, infected root canals. One combination that is effective against bacteria commonly found in infected root canals is a mixture of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole and cefaclor. Hoshino et al.15 performed a laboratory study testing the antibacterial efficacy of these drugs alone and in combination against bacteria from infected dentin, infected pulp and periapical lesions. Alone, none of the drugs resulted in the complete elimination of bacteria. However, in combination, these drugs provided a consistent sterilization of all bacterial samples. In addition, Sato et al.16 determined that this drug combination was effective for eliminating bacteria in the deep layers of root dentin. However, possible complications such as crown discoloration,17 development of resistant bacterial strains18,19,20 and allergic reactions to the intracanal medication21,22,23 may occur after the use of these antibiotics.

It is difficult or impossible to obtain a perfectly standardized radiographic image. In the present case reports, preoperative and final follow-up radiographs differed from each other, which precluded a proper evaluation of the radiographic changes occurring after revascularization. To minimize differences among the obtained radiographic images, we used the TurboReg plug-in of the ImageJ analysis program.

The main difference in the present case reports compared to earlier reports is the longer follow-up period. Although some successful revascularization case reports have been reported, long-term follow-up cases have rarely been reported. Thibodeau and Trope reported only a 9.5-month follow-up of a revascularized necrotic tooth.24 Shin et al. reported revascularization of a necrotic tooth after a 19-month follow-up.25 Jung et al. reported 11 revascularized teeth; however, only one case was reported with over a 2-year follow-up.13 Another clinical study reported three revascularization cases, but follow-up periods of these cases were also only between 15 and 19 months.26 The present study provides follow-up information for 24, 48 and 42 months for cases 1, 2 and 3. All of the revascularized teeth showed satisfactory clinical and radiographical performances at long-term follow-ups. Therefore, we consider that the revascularization technique can be regarded as a reliable treatment modality for clinical use.

Conclusion

These case reports demonstrate the long-term reliable prognoses of revascularization for immature necrotic teeth. In well-selected cases, the revascularization technique may be a trustworthy alternative to conventional apexogenesis or apexification.

References

Cvek M . Prognosis of luxated non-vital maxillary incisors treated with calcium hydroxide and filled with gutta-percha. A retrospective clinical study. Endod Dent Traumatol 1992; 8( 2): 45–55.

Mente J, Hage N, Pfefferle T et al. Mineral trioxide aggregate apical plugs in teeth with open apical foramina: a retrospective analysis of treatment outcome. J Endod 2009; 35( 10): 1354–1358.

Al Ansary MA, Day PF, Duggal MS, Brunton PA . Interventions for treating traumatized necrotic immature permanent anterior teeth: inducing a calcific barrier & root strengthening. Dent Traumatol 2009; 25( 4): 367–379.

Sheehy EC, Roberts GJ . Use of calcium hydroxide for apical barrier formation and healing in non-vital immature permanent teeth: a review. Br Dent J 1997; 183( 7): 241–246.

Torabinejad M, Parirokh M . Mineral trioxide aggregate: a comprehensive literature review—Part II: Leakage and biocompatibility investigations. J Endod 2010; 36( 2): 190–202.

Shah N, Logani A, Bhaskar U, Aggarwal V . Efficacy of revascularization to induce apexification/apexogensis in infected, nonvital, immature teeth: a pilot clinical study. J Endod 2008; 34( 8): 919–925; Discussion 1157.

Sonoyama W, Liu Y, Fang D et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated functional tooth regeneration in swine. PLoS ONE 2006; 1: e79.

Sonoyama W, Liu Y, Yamaza T et al. Characterization of the apical papilla and its residing stem cells from human immature permanent teeth: a pilot study. J Endod 2008; 34( 2): 166–171.

Huang GT, Sonoyama W, Liu Y et al. The hidden treasure in apical papilla: the potential role in pulp/dentin regeneration and bioroot engineering. J Endod 2008; 34( 6): 645–651.

Bose R, Nummikoski P, Hargreaves K . A retrospective evaluation of radiographic outcomes in immature teeth with necrotic root canal systems treated with regenerative endodontic procedures. J Endod 2009; 35( 10): 1343–1349.

Cehreli ZC, Isbitiren B, Sara S, Erbas G . Regenerative endodontic treatment (revascularization) of immature necrotic molars medicated with calcium hydroxide: a case series. J Endod 2011; 37( 9): 1327–1330.

Chueh LH, Huang GT . Immature teeth with periradicular periodontitis or abscess undergoing apexogenesis: a paradigm shift. J Endod 2006; 32( 12): 1205–1213.

Jung IY, Lee SJ, Hargreaves KM . Biologically based treatment of immature permanent teeth with pulpal necrosis: a case series. J Endod 2008; 34( 7): 876–887.

Banchs F, Trope M . Revascularization of immature permanent teeth with apical periodontitis: new treatment protocol? J Endod 2004; 30( 4): 196–200.

Hoshino E, Kurihara-Ando N, Sato I et al. In-vitro antibacterial susceptibility of bacteria taken from infected root dentine to a mixture of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole and minocycline. Int Endod J 1996; 29( 2): 125–130.

Sato I, Ando-Kurihara N, Kota K et al. Sterilization of infected root-canal dentine by topical application of a mixture of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole and minocycline in situ. Int Endod J 1996; 29( 2): 118–124.

Kim JH, Kim Y, Shin SJ et al. Tooth discoloration of immature permanent incisor associated with triple antibiotic therapy: a case report. J Endod 2010; 36( 6): 1086–1091.

Greenstein G, Polson A . The role of local drug delivery in the management of periodontal diseases: a comprehensive review. J Periodontol 1998; 69( 5): 507–520.

Eickholz P, Kim TS, Burklin T et al. Non-surgical periodontal therapy with adjunctive topical doxycycline: a double-blind randomized controlled multicenter study. J Clin Periodontol 2002; 29( 2): 108–117.

Slots J . Selection of antimicrobial agents in periodontal therapy. J Periodontal Res 2002; 37( 5): 389–398.

de Paz S, Perez A, Gomez M et al. Severe hypersensitivity reaction to minocycline. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 1999; 9( 6): 403–404.

Hausermann P, Scherer K, Weber M, Bircher AJ . Ciprofloxacin-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis mimicking bullous drug eruption confirmed by a positive patch test. Dermatology 2005; 211( 3): 277–280.

Isik SR, Karakaya G, Erkin G, Kalyoncu AF . Multidrug-induced erythema multiforme. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2007; 17( 3): 196–198.

Thibodeau B, Trope M . Pulp revascularization of a necrotic infected immature permanent tooth: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dent 2007; 29( 1): 47–50.

Shin SY, Albert JS, Mortman RE . One step pulp revascularization treatment of an immature permanent tooth with chronic apical abscess: a case report. Int Endod J 2009; 42( 12): 1118–1126.

Ding RY, Cheung GS, Chen J et al. Pulp revascularization of immature teeth with apical periodontitis: a clinical study. J Endod 2009; 35( 5): 745–749.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, DS., Park, HJ., Yeom, JH. et al. Long-term follow-ups of revascularized immature necrotic teeth: three case reports. Int J Oral Sci 4, 109–113 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijos.2012.23

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijos.2012.23

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Advances in Research on Stem Cell-Based Pulp Regeneration

Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine (2021)

-

What is the best long-term treatment modality for immature permanent teeth with pulp necrosis and apical periodontitis?

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (2021)