Abstract

Blood pressure (BP) is important to measure during pregnancy because it provides the basis for classifying hypertension, which has several etiologies. Similarly, monitoring home and ambulatory BP can provide useful information outside a medical setting for adults who are not pregnant. Office BP is higher during early pregnancy in primiparous women than in multiparous women, whereas out-of-office BP does not differ between them. White-coat hypertension might be benign compared with hypertension determined from ambulatory BP values that might be associated with a high risk for preeclampsia. Although reference values have been proposed on the basis of the distribution of BP among normotensive pregnant women, prognosis-based reference values are also required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Blood pressure (BP) is important to measure during pregnancy because it provides the basis for classifying hypertension. BP can be monitored in several ways. Office BP measured in a medical environment is used for diagnosis. However, for monitoring BP outside the office, ambulatory BP monitoring and home BP monitoring have recently been recommended to diagnose hypertension in nonpregnant adults. There is a little difficulty in diagnosing hypertension in pregnancy because there are several subclassifications and several hemodynamic changes during pregnancy. The evidence of the benefits of measuring ambulatory BP and home BP in pregnant women has been accumulating.

Definition of hypertension in pregnancy

Hypertension with or without proteinuria that emerges after 20 weeks of gestation, but resolves up to 12 weeks postpartum, is defined as pregnancy-induced hypertension in these guidelines of the Japanese Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy.1 In the guidelines, pregnancy-induced hypertension is subclassified as gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia and superimposed preeclampsia. Extant hypertension before pregnancy is described as pregnancy complicated by hypertension in the guidelines. Hypertensive disorders during pregnancy include pregnancy-induced hypertension and pregnancy complicated by hypertension. Proteinuria occurring in normotensive pregnant women is classified as gestational proteinuria and is excluded from the current definition of pregnancy-induced hypertension. The reported incidence of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy is 5% of all pregnancies and is 11% of primiparous women.2 Preeclampsia accounts for 3–5% of all pregnancies.3 Hypertension is defined as office values of systolic/diastolic BP ⩾140/90 mm Hg. Office BP values of 140–159/90–109 and ⩾160/110 mm Hg are classified as mild and severe hypertension, respectively. Proteinuria <2.0 g for 24 h or <3+ is defined as mild, and proteinuria ⩾2.0 g for 24 h or ⩾3+ is defined as severe. Other subclassifications are on the basis of the period of occurrence. The Japanese guidelines classify pregnancy-induced hypertension that occurs before or after 32 weeks of gestation as early- and late-onset, respectively. This classification differs somewhat from other classification systems.4, 5, 6, 7, 8

The reported etiology of pregnancy-induced hypertension varies. Insufficient remodeling of the uterine spiral artery during placentation is one proposed cause of early-onset pregnancy-induced hypertension or hypertension that develops into preeclampsia.9 Several cardiovascular risk factors are similar between gestational hypertension and preeclampsia,10 and factors associated with immunological mechanisms, primipara, pregnancy during adolescence, autoimmune diseases and primigravida infection are considered risk factors.11, 12

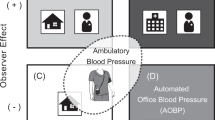

BP can be monitored in several ways. Office BP measured in a medical environment is used for diagnosis. However, monitoring BP outside the office at home and while ambulatory in a nonmedical environment has recently been recommended to diagnose hypertension in nonpregnant adults. In Canada, 83% of obstetricians tried to exclude white-coat hypertension, and 78 and 12% of them encourage BP monitoring at home and while ambulatory in nonmedical settings, respectively.13

Ambulatory BP monitoring

Monitoring ambulatory BP is useful not only for diagnosing masked and white-coat hypertension, but also for assessing circadian variations in BP. Japanese health insurance has covered this type of monitoring since 2008. Proposed normal ranges of diurnal BP before 16 weeks, between 26 and 30 weeks, and after 30 weeks of gestation on the basis of the data derived from 276 pregnant women are <130/77, <133/81 and <135/86 mm Hg, respectively.14 BP varies diurnally during pregnancy with reported systolic and diastolic nocturnal declines of 12–14 and 18–19%, respectively.14 Diurnal variations in BP and heart rate become attenuated during normal late pregnancy, because 80–90% of individuals with extreme hypertension or severe preeclampsia have attenuated nocturnal declines in BP (non-dippers; ND) or increased nocturnal BP (risers; R).14 One report suggests that the nocturnal decline in BP is attenuated before the onset of preeclampsia.15

Ayala and Hermida16 found no significant difference in BP between primiparous and multiparous pregnant women after adjusting for possible confounding factors, whereas office BP might differ between them. Another study found that 32% of hypertensive women had white-coat hypertension during early pregnancy on the basis of ambulatory BP values.17 After excluding white-coat hypertension, 22% of pregnant women who were considered hypertensive according to ambulatory BP and 8% of those with white-coat hypertension on the basis of ambulatory BP developed preeclampsia.17 Newborns who were small for their gestational age were more closely associated with ambulatory BP than office BP. The risk of small for their gestational age per 10 mm Hg elevation in ambulatory and office systolic BP was 1.74- and 1.40-fold higher, respectively, and office systolic BP did not reach statistical significance.18

Home BP monitoring

Home BP should have priority when office and home BP values differ among subjects who are not pregnant according to the Japanese guidelines for treating hypertension,19 and evidence of the benefits for measuring home BP in pregnant women has been accumulating. In a joint statement of the American Heart Association, American Society of Hypertension and the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Society of Hypertension,20 home BP monitoring during pregnancy is cited as being theoretically ideal for determining changes in BP during pregnancy because it is the optimal way to provide multiple readings recorded at the same time of day over prolonged periods.21 The Guidelines of the European Society of Hypertension state that home BP monitoring, although not commonly practiced, has considerable potential for improving the management of pregnant women.22 The recent task force recommendations from ACOG (2013) suggest that pregnant women with chronic hypertension or with poorly controlled BP should measure BP at home.5

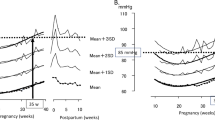

Home BP slightly decreases in normal pregnant women and reaches a nadir ~20 weeks of gestation. Systolic and diastolic BP increases by 10 and 7 mm Hg, respectively, throughout 40 weeks of gestation.23 The same study found that both environmental temperature and gestational age affect home BP values. Notably, home systolic/diastolic BP during pregnancy changed by 12.8/12.5 and 3.1/3.0 mm Hg in women who delivered in January and July, respectively.23 Hypertension during pregnancy has not yet been defined on the basis of home BP monitoring. The critical level of hypertension determined from BP measured at home in subjects who were not pregnant might be inadequate for those who are.24 Similar to the diagnostic criteria for hypertension in subjects who were not pregnant, evidence should be on the basis of outcomes of pregnancy and newborns. A cross-sectional study of 4021 multiethnic pregnant women at an outpatient clinic of a university hospital in Switzerland reported that values for automated BP in >95% of pregnant women were 128/74, 128/78 and 131/78 mm Hg at 12, 20 and 36 weeks of gestation, respectively.25 Denolle et al.26 analyzed data from six French hospitals and proposed that the upper normal limits of mean home BP +2 s.d. were 118/73, 117/73 and 121/80 mm Hg, and 116/70, 113/70 and 118/76 mm Hg in >95% of pregnant women during the first, second and third trimesters, respectively. Mean home BP values (±s.d.) among 101 normotensive Japanese women were 101.8±7.9/59.8±5.8 and 110.1±9.7/66.8±7.7 mm Hg at 20 and 40 weeks of gestation, respectively.27 Home BP values were almost identical between these two studies.

Ishikuro et al.28 reported that office BP was significantly higher in primiparous women compared with multiparous women, whereas home BP did not significantly differ between the groups. They also reported that the white-coat effect was more obvious in primiparous, rather than multiparous, women.29 One study found that 76% of 57 hypertensive pregnant women who tele-transmitted their BP values measured at home had white-coat hypertension.30

Home BP is also associated with prognosis among women who are not pregnant. Iwama et al.31 reported that birth weight was more significantly associated with home BP than office BP. An elevation of 1 s.d. in home and clinical diastolic BP was associated with a 1.28- and 1.06-fold higher risk, respectively, for a 500 g lower birth weight. When new parameters were compared with office BP, other indexes such as the prognosis of newborns should be included in a gold standard as Hermida et al.32 discussed.33 For long-term prognosis, maternal gestational hypertension defined by office BP was reported to be associated with home BP as well as office BP measured 7 years after delivery.32 In such situations, other indexes instead of office BP during pregnancy may reflect the ideal association between gestational hypertension and long-term prognosis.

Labor-onset hypertension and out-of-office BP measurement

Labor-onset and postpartum hypertension have recently been emphasized. Goel et al.34 reported that of 184 (18.6%) women who were hypertensive among 968 pregnant women, 77 (7.8%) of them developed hypertension only after delivery.34 They also associated a high body mass index, a history of diabetes mellitus and sFlt-1/PIGF during pregnancy with BP after pregnancy. Ohno et al.35 reported that risk factors for labor-onset hypertension comprised more advanced age, higher body mass index at delivery, relatively higher BP at 36 weeks of pregnancy, positive proteinuria and edema. Out-of-office BP values between labor-onset and postpartum hypertension have not been reported. Out-of-office BP monitoring during this period might have an important role in the treatment and management of hypertensive pregnant women.

Conclusions

Prognostic factors might differ according to pathophysiology among hypertensive pregnant women. Out-of-office BP might improve the accuracy of classifying hypertension during pregnancy. Fine classification might help to identify novel prognostic factors and improve treatment. Early treatment strategies to improve the prognosis of both mother and newborn should be on the basis of an early fine diagnosis, especially for out-of-office BP values.

References

Takagi K, Yamasaki M, Nakamoto O, Saito S, Suzuki H, Seki H, Takeda S, Ohno Y, Sugimura M, Suzuki Y, Watanabe K, Matsubara K, Makino S, Metoki H, Yamamoto T . A review of best practice guide 2015 for care and treatment of hypertension in pregnancy. Hypertens Res Pregnancy 2015; 3: 65–103.

Villar J, Say L, Shennan A, Lindheimer M, Lindheimer M, Duley L, Conde-Agudelo A, Merialdi M . Methodological and technical issues related to the diagnosis, screening, prevention and treatment of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2004; 85: S28–S41.

Redman CW, Sargent IL . Latest advances in understanding preeclampsia. Science 2005; 308: 1592–1594.

National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health (UK). Hypertension in pregnancy: the management of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy. NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 107. RCOG Press, London. 2010.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Hypertension in Pregnancy 2013.

Magee LA, Pels A, Helewa M, Rey E, von Dadelszen P Canadian Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy (HDP) Working Group. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Pregnancy Hypertens 2014; 4: 105–145.

Lowe SA, Bowyer L, Lust K, McMahon LP, Morton MR, North RA, Paech MJ, Said JM Society of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand. The SOMANZ guidelines for the management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy 2014. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2015; 55: 11–16.

Tranquilli AL, Brown MA, Zeeman GG, Dekker G, Sibai BM . The definition of severe and early-onset preeclampsia. Statements from the International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP). Pregnancy Hypertens 2013; 3: 44–47.

Khong TY, De Wolf F, Robertson WB, Brosens I . Inadequate maternal vascular response to placentation in pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia and by small-for-gestational age infants. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1986; 93: 1049–1059.

Egeland GM, Klungsøyr K, Øyen N, Tell GS, Næss Ø, Skjærven R . Preconception cardiovascular risk factor differences between gestational hypertension and preeclampsia: cohort Norway study. Hypertension 2016; 67: 1173–1180.

Duckitt K, Harrington D . Risk factors for pre-eclampsia at antenatal booking: systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ 2005; 330: 565.

Gold RA, Gold KR, Schilling MF, Modilevsky T . Effect of age, parity, and race on the incidence of pregnancy associated hypertension and eclampsia in the United States. Pregnancy Hypertens 2014; 4: 46–53.

Dehaeck U, Thurston J, Gibson P, Stephanson K, Ross S . Blood pressure measurement for hypertension in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2010; 32: 328–334.

Brown MA, Robinson A, Bowyer L, Buddle ML, Martin A, Hargood JL, Cario GM . Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in pregnancy: what is normal? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998; 178: 836–842.

Cugini P, Di Palma L, Battisti P, Leone G, Pachí A, Paesano R, Masella C, Stirati G, Pierucci A, Rocca AR, Morabito S . Describing and interpreting 24-hour blood pressure patterns in physiologic pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992; 166: 54–60.

Ayala DE, Hermida RC . Influence of parity and age on ambulatory monitored blood pressure during pregnancy. Hypertension 2001; 38: 753–758.

Brown MA, Mangos G, Davis G, Homer C . The natural history of white coat hypertension during pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2005; 112: 601–606.

Eguchi K, Ohmaru T, Ohkuchi A, Hirashima C, Takahashi K, Suzuki H, Kario K, Matsubara S, Suzuki M . Ambulatory BP monitoring and clinic BP in predicting small-for-gestational-age infants during pregnancy. J Hum Hypertens 2016; 30: 62–67.

Shimamoto K, Ando K, Fujita T, Hasebe N, Higaki J, Horiuchi M, Imai Y, Imaizumi T, Ishimitsu T, Ito M, Ito S, Itoh H, Iwao H, Kai H, Kario K, Kashihara N, Kawano Y, Kim-Mitsuyama S, Kimura G, Kohara K, Komuro I, Kumagai H, Matsuura H, Miura K, Morishita R, Naruse M, Node K, Ohya Y, Rakugi H, Saito I, Saitoh S, Shimada K, Shimosawa T, Suzuki H, Tamura K, Tanahashi N, Tsuchihashi T, Uchiyama M, Ueda S, Umemura S Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee for Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension.. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2014). Hypertens Res 2014; 37: 253–390.

Pickering TG, Miller NH, Ogedegbe G, Krakoff LR, Artinian NT, Goff D American Heart Association, American Society of Hypertension, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association.. Call to action on use and reimbursement for home blood pressure monitoring: a joint scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American Society Of Hypertension, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Hypertension 2008; 52: 10–29.

Pickering TG . Reflections in hypertension: how should blood pressure be measured during pregnancy? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2005; 7: 46–49.

Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, Bilo G, de Leeuw P, Imai Y, Kario K, Lurbe E, Manolis A, Mengden T, O’Brien E, Ohkubo T, Padfield P, Palatini P, Pickering T, Redon J, Revera M, Ruilope LM, Shennan A, Staessen JA, Tisler A, Waeber B, Zanchetti A, Mancia G, . ESH Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring. European Society of Hypertension guidelines for blood pressure monitoring at home: a summary report of the Second International Consensus Conference on Home Blood Pressure Monitoring. J Hypertens 2008; 26: 1505–1526.

Metoki H, Ohkubo T, Obara T, Akutsu K, Yamamoto M, Ishikuro M, Sakurai K, Iwama N, Katagiri M, Sugawara J, Hirose T, Sato M, Kikuya M, Yagihashi K, Matsubara Y, Yaegashi N, Mori S, Suzuki M, Imai Y BOSHI Study Group. Daily serial hemodynamic data during pregnancy and seasonal variation: the BOSHI study. Clin Exp Hypertens 2012; 34: 290–296.

Rey E, Pilon F, Boudreault J . Home blood pressure levels in pregnant women with chronic hypertension. Hypertens Pregnancy 2007; 26: 403–414.

Ochsenbein-Kolble N, Roos M, Gasser T, Huch R, Huch A, Zimmermann R . Cross sectional study of automated blood pressure measurements throughout pregnancy. BJOG 2004; 111: 319–325.

Denolle T, Daniel JC, Calvez C, Ottavioli JN, Esnault V, Herpin D . Home blood pressure during normal pregnancy. Am J Hypertens 2005; 18: 1178–1180.

Metoki H, Ohkubo T, Watanabe Y, Nishimura M, Sato Y, Kawaguchi M, Hara A, Hirose T, Obara T, Asayama K, Kikuya M, Yagihashi K, Matsubara Y, Okamura K, Mori S, Suzuki M, Imai Y BOSHI Study Group. Seasonal trends of blood pressure during pregnancy in Japan: the babies and their parents’ longitudinal observation in Suzuki Memorial Hospital in Intrauterine Period study. J Hypertens 2008; 26: 2406–2413.

Ishikuro M, Obara T, Metoki H, Ohkubo T, Yamamoto M, Akutsu K, Sakurai K, Iwama N, Katagiri M, Yagihashi K, Yaegashi N, Mori S, Suzuki M, Kuriyama S, Imai Y . Blood pressure measured in the clinic and at home during pregnancy among nulliparous and multiparous women: the BOSHI study. Am J Hypertens 2013; 26: 141–148.

Ishikuro M, Obara T, Metoki H, Ohkubo T, Iwama N, Katagiri M, Nishigori H, Narikawa Y, Yagihashi K, Kikuya M, Yaegashi N, Hoshi K, Suzuki M, Kuriyama S, Imai Y . Parity as a factor affecting the white-coat effect in pregnant women: the BOSHI study. Hypertens Res 2015; 38: 770–775.

Denolle T, Weber JL, Calvez C, Getin Y, Daniel JC, Lurton O, Cheve MT, Marechaud M, Bessec P, Carbonne B, Razafintsalama T . Diagnosis of white coat hypertension in pregnant women with teletransmitted home blood pressure. Hypertens Pregnancy 2008; 27: 305–313.

Iwama N, Metoki H, Ohkubo T, Ishikuro M, Obara T, Kikuya M, Yagihashi K, Nishigori H, Sugiyama T, Sugawara J, Yaegashi N, Hoshi K, Suzuki M, Kuriyama S, Imai Y BOSHI Study Group. Maternal clinic and home blood pressure measurements during pregnancy and infant birth weight: the BOSHI study. Hypertens Res 2016; 39: 151–157.

Hermida RC, Ayala DE . Prognostic value of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in pregnancy. J Hypertens 2010; 28: 1110–1111.

Hosaka M, Asayama K, Staessen JA, Tatsuta N, Satoh M, Kikuya M, Ohkubo T, Satoh H, Imai Y, Nakai K . Relationship between maternal gestational hypertension and home blood pressure in 7-year-old children and their mothers: Tohoku Study of Child Development. Hypertens Res 2015; 38: 776–782.

Goel A, Maski MR, Bajracharya S, Wenger JB, Zhang D, Salahuddin S, Shahul SS, Thadhani R, Seely EW, Karumanchi SA, Rana S . Epidemiology and mechanisms of de novo and persistent hypertension in the postpartum period. Circulation 2015; 132: 1726–1733.

Ohno Y, Terauchi M, Tamakoshi K, Shiozaki A, Saito S . The risk factors for labor onset hypertension. Hypertens Res 2016; 39: 260–265.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grants for Scientific Research (Nos. 18390192, 21390201, 22890017, 23590771, 23659347, 24689061, 25670314, 26860412 and 16H05243) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, a Grant-in-Aid (H21-Junkankitou[Seishuu]-Ippan-004) from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Health and Labor Sciences Research Grants, Japan, a Grant-in-Aid for the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) fellows (19.7152), Grants from the Takeda Science Foundation and Grants from the OTC Self-Medication Promotion Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Aside from the present study, HM is executing collaborative research with Omron Healthcare. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Metoki, H., Iwama, N., Ishikuro, M. et al. Monitoring and evaluation of out-of-office blood pressure during pregnancy. Hypertens Res 40, 107–109 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2016.112

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2016.112

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Differences in visit-to-visit blood pressure variability between normotensive and hypertensive pregnant women

Hypertension Research (2019)

-

The impact of salt intake during and after pregnancy

Hypertension Research (2018)