Abstract

To elucidate the origin of African-specific mtDNA lineages, revealed previously in Slavonic populations (at frequency of about 0.4%), we completely sequenced eight African genomes belonging to haplogroups L1b, L2a, L3b, L3d and M1 gathered from Russians, Czechs, Slovaks and Poles. Results of phylogeographic analysis suggest that at least part of the African mtDNA lineages found in Slavs (such as L1b, L3b1, L3d) appears to be of West African origin, testifying to an opportunity of their occurrence as a result of migrations to Eastern Europe through Iberia. However, a prehistoric introgression of African mtDNA lineages into Eastern Europe (approximately 10 000 years ago) seems to be probable only for European-specific subclade L2a1a, defined by coding region mutations at positions 6722 and 12903 and detected in Czechs and Slovaks. Further studies of the nature of African admixture in gene pools of Europeans require the essential enlargement of databases of African complete mitochondrial genomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It has been previously found that African mtDNA lineages represent about 1% of Eurasian mtDNAs.1 Majority of them occurred in regions closest to North Africa – the Near East, Iberia and southern Europe.1, 2, 3, 4 It has been suggested that African mtDNAs appeared in Europe mostly as a result of the Atlantic slave trade beginning in seventeenth century, with Portugal being the destination point playing predominant role in further dispersal.3 In addition, the medieval Arab/Berber conquest of Iberia might have also contributed to this process.5, 6 As for eastern Europe, it seems that only African children's traffic from Turkey to Russia at the end of seventeenth century might have played the leading role in African slave trade.7 African children were bought on the Ottoman markets by Russian traders who brought them to Russia. It is impossible to present any detailed data as no research has ever been made to determine the exact amount. However, it seems that the inflow of Africans was not significant.

Genetic studies have shown that African-specific lineages are very rare in eastern European populations. They have not been found in a large sample of indigenous eastern Europeans, including Mordva, Mari, Udmurt, Tatar, Chuvash, Komi, Bashkir, Karels, Estonians, Lithuanians and Latvians.8, 9, 10 Less than 0.5% of African mtDNAs belonging to different haplogroups (L1b, L3b and M1) were detected in Russians whose origin is thought to be the result of an admixture between the Slavs and indigenous pre-Slavonic tribes of eastern Europe that occurred in the early Middle Ages due to migrations of Slavs from their putative homeland in central Europe.11, 12 It is noteworthy that African mtDNAs have been detected also in other Slavonic populations – in Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Bosnians13, 14, 15, 16 and Bulgarians.17 The precise ancestry of these mtDNAs is difficult to trace. Some African mtDNAs revealed in Europe are identical to those found in Africa; however some of them appear to be unique being found only in Europe.18, 19 For this, several explanations can be proposed: the African mtDNAs detected in Europe are either present in Africa but not yet detected, or they are of African origin but have been lost among Africans, or their unique mutations have occurred exclusively in Europe. The question concerning the time of these unique mutations to originate appears to be of high importance.

In the previous studies, based on the hypervariable segment I (HVS I) variation, it has been proposed that the evolutionary age of two clusters of African mtDNAs (marked by unique mutations at 16362 within haplogroup L1b and 16294 within haplogroup L3b) do not exceed 6500 years.18 Whereas, another study has shown that unique cluster marked by the 16175 transition within haplogroup L1b has not been found in Africa but is present in Germany,17 Russia11 and in medieval (twelfth–thirteenth century) population from south Iberia (Spain),19 suggesting that the ancestor of this motif arrived from Africa to Europe where the 16175 mutation occurred. The divergence time estimation for this cluster in Europe is around 20 000±16 000 years, pointing to a prehistoric arrival of the basic African L1b-motif in Europe.19 Meanwhile, it is likely that complete mtDNA sequencing will considerably improve the phylogenetic resolution that allows us to determine the ancestry of certain European lineages belonging to the African mtDNA haplogroups with a higher accuracy. The present research was aimed at elucidating the origin of eight African-specific mtDNA haplotypes, revealed previously in different Slavonic populations: Russians, Czechs, Slovaks and Poles.

Materials and methods

In the present study, we completely sequenced eight African haplotypes of mtDNAs revealed previously in 2018 individuals from Slavonic populations of Eastern and Central Europe by means of mtDNA control region sequencing and coding region RFLP analysis (Table 1). All individuals with African variants of mtDNA identified themselves as ethnical Slavs (ie ‘indigenous’ Russians, Slovaks, Czechs or Poles) and were unaware of their African ancestry until molecular genetic studies.

Whole mitochondrial genomes were amplified and sequenced by means of the procedures described in Torroni et al.21 Sequencing reactions were run on Applied Biosystems 3130 Genetic Analyzer. Sequences were edited and aligned by SeqScape v. 2.5 software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and mutations were scored relative to the rCRS.20 The eight complete mtDNA sequences have been submitted to GenBank (accession numbers EU200759–66).

For comparative purposes, a large number of published African and Eurasian mtDNA HVS I sequences and any available HVS II or RFLP data were used (see references1, 18, 19, 22, 23). In addition, complete or nearly complete mtDNA sequences pooled in MitoMap mtDNA tree24 were taken into analysis. The complete mtDNA tree was reconstructed manually and verified by using median-joining algorithm with NETWORK 4.1.0.9.25 For phylogeny construction, the length variation in the poly-C stretches at nts 16180–16193 and 309–315 were not used. Haplogroup divergence estimates ρ and their standard errors were calculated as average number of substitutions in the mtDNA coding region from the ancestral sequence type.26, 27 To estimate the time to the most recent common ancestor of each cluster, the evolutionary rate corresponding to 5140 years per substitution in the coding region was used.28

Results and discussion

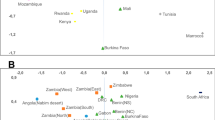

Haplogroup L1b lineage detected in Russian individual is characterized by the transition at position 16175 that is a marker of ‘European-specific’ L1b-subcluster revealed also in Germany and medieval Spain (Table 1). Comparison of its complete genome sequence with the data presented in MitoMap mtDNA tree24 shows that Russian sample belongs to L1b1a subcluster defined by mutations at positions 2768 and 5393 (Figure 1). This subcluster is widespread in Africa being found in 22 individuals presented in MitoMap mtDNA tree. A coalescence time estimate of subcluster L1b1a (calculated from the average sequence divergence and its standard error according to Sailard et al27) corresponds to 8943±1400 years, suggesting a relatively recent (post-Neolithic or later) arrival of the L1b1a lineage into Europe. Note that it is only the approximate lower time boundary of the actual arrival of this mtDNA lineage.

Complete genome-based phylogenetic tree of African-specific haplogroups found in Slavonic gene pools. The tree is rooted in macrohaplogroup L. Numbers along links refer to substitutions scored relative to the rCRS.20 Transversions are further specified, recurrent mutations are underlined, ‘d’ denotes a deletion. Two additional complete sequences were taken from the literature29, 30 and designated by AO and AT, respectively, followed by ‘_’ and the original sample code.

Haplogroup L2a samples were found in three individuals, two of whom are Slovaks and one comes from the Czech Republic. It is noteworthy that among them there is L2a branch defined by mutation at 16218 that is absent in published HVS I L2a data from Africa and Eurasia (Table 1). Complete genome sequencing demonstrates that these two individuals are characterized by two coding region mutations (at positions 6722 and 12903) and represent a branch that is absent among 50 L2a individuals collected together in MitoMap mtDNA tree (Figure 1). A coalescence time of this branch is estimated as 10 280±5140 years, though inferred only from two complete genomes. Slovak L2a1 haplotype characterized by transition at 16051 also seems to be very scarce. This control region sequence type has been recently detected in different parts of Eurasia only twice – in France31 and in Eastern Iran.32 Based on coding region variation data and comparison with MitoMap tree, this haplotype belongs to a specific subcluster defined by mutations at positions 3010 and 6663. Aforementioned subcluster seems to be ancient, with an estimated coalescence time of 24 672±3561 years for 10 mtDNA genomes analyzed.

Among Poles, the only African haplotype belonging to haplogroup L3d has been detected in population studies (Table 1). This haplotype contains a characteristic HVS I motif (16124–16223) of haplogroup L3d and complete mtDNA sequencing indicated that it belongs to the branch defined by mutation at position 6272 (Figure 1). This branch combines also two African individuals.30, 33 The age of this subcluster is 15 420±5140 years.

There is also one more African mtDNA haplotype detected among Russians belonging to haplogroup L3b1. It is characterized by HVS I key mutation at position 16294 that is rare both in African and European populations being found only in one Saharawi individual from northwest Africa,34 in two black individuals from Brazil23 and in one Italian individual from Tuscany.35 Complete genome sequencing demonstrates that Russian L3b sample belongs to a specific branch L3b1a defined by coding region mutations at positions 9079 and 15664 that were also found in two African individuals.36 The age of this subcluster is estimated as 20 560±5935 years.

It is interesting that haplogroup M1 lineages have been detected in two different Russian populations – in northwest region (two cases in Volot city) and in the Volga–Oka region (one case in Vladimir city). Haplogroup M1 is geographically restricted to East and North Africa, although it can be found at very low frequencies in populations from the Near East, the Caucasus and southern Europe.17 Meanwhile, M1 lineages revealed in Russians belong to a specific branch undergoing a back mutation at position 16223 (Table 1). Similar HVS I motifs have been detected previously in some African populations: in Chad,22 Egypt and Morocco.29 Complete genome sequencing shows that all Russian M1 lineages, together with the Egyptian29 and Spanish Basque37 ones, appear to be a part of the subcluster M1a3b defined by coding region mutation at position 12414 (Figure 1). In addition, related M1a3a lineages have been also found in the Mediterranean area – in Italians and Berbers of Morocco.29 The estimated age of subcluster M1a3b amounts 14 145±4262 years.

To sum up, it is striking that gene pools of different Slavonic populations include African-specific mtDNA lineages, some of which have their most related counterparts in Europe instead of Africa (such as haplotypes belonging to subclusters L1b1a and L2a1a). It is noteworthy that according to the results of phylogeographic studies, almost all African mtDNA lineages detected in the Slavs seem to be of West African origin. Only the haplogroup L2a is widespread within all regions of Africa, whereas haplogroups L1b, L3b1 and L3d are specific to West Africa.1 In Northwest Africa, haplogroup M1 has been found at high frequencies in Algerians, and at lower frequency in Tunisians, Mozabites and Morroccan Arabs, showing a slight east–west cline.34 Haplogroup M1 is rare in Iberia, but the presence of North African M1 mtDNA in the Basques remains that pre-date the Muslim invasion (eighth century) points to the prehistoric arrival of M1 lineages in Iberia.38 Therefore, since most of the African lineages found in eastern European populations are present in West Africa, their migration to eastern Europe likely took them through Iberia.

In this respect, a possible explanation for presence of African mtDNA lineages in gene pools of eastern Europeans is that the Franco-Cantabrian refuge area of southwestern Europe might be the source of late glacial expansions leading to dispersal of some Northwest African mtDNAs in central and northeastern parts of Europe. It has been previously shown that ancient Iberian carriers of West Eurasian haplogroups H1, H3, V, U5b1b and U8a have participated in demographic reexpansion to repopulate Central Europe in the last interglacial periods (10 000–15 000 years ago).39, 40, 41 According to the data obtained in our study, it seems probable that Northwest Africans also contributed their mtDNA lineages to ancient Iberians, and further, via their gene pool migrations, to Europeans. Meanwhile, the strongest argument in favor of the hypothesis of the prehistoric introgression of African mtDNA lineages into the European gene pool would come from a finding of the appropriately dated European-specific subclades of the African haplogroups. However, the only two lineages that appear to represent European-specific subclades are L1b1a and L2a1a, but the lower boundary of about 9000 years for the potential introgression of L1b1a is not a strong argument for the presence of this lineage in the Franco-Cantabrian refuge area. Coalescence time estimate of 10 280±5140 years for European-specific subclade L2a1a is by a margin consistent with the post-Last Glacial Maximum expansion scenario. One should note, however, that absence of this subclade among Africans does not mean absence of this lineage in Africa in general due to relatively small sample size of African L2a genomes completely sequenced to date.

Therefore, the present data do not allow us to infer exactly when the African mtDNA lineages were introduced into gene pool of eastern Europeans. Both prehistoric and more recent gene flows (for instance, such as the potential Jewish L2a1 contribution42) might have led to African mtDNA lineages admixture into Slavonic gene pools. More extensive studies of African populations based on complete mtDNA sequencing should provide more precise information about the genetic relationships between mitochondrial gene pools of Africans and Europeans.

Accession codes

References

Salas A, Richards M, De la Fe T et al: The making of the African mtDNA landscape. Am J Hum Genet 2002; 71: 1082–1111.

Richards M, Rengo C, Cruciani F et al: Extensive female mediated gene flow from sub-Saharan Africa into Near Eastern Arab populations. Am J Hum Genet 2003; 72: 1058–1064.

Salas A, Richards M, Lareu M-V et al: The African diaspora: mitochondrial DNA and the Atlantic slave trade. Am J Hum Genet 2004; 74: 454–465.

Pereira L, Cunha C, Amorim A : Predicting sampling saturation of mtDNA haplotypes: an application to an enlarged Portuguese database. Int J Legal Med 2004; 118: 132–136.

Larruga JM, Diez F, Pinto FM, Flores C, Gonzalez AM : Mitochondrial DNA characterisation of European isolates: the Maragatos from Spain. Eur J Hum Genet 2001; 9: 708–716.

Gonzalez AM, Brehm A, Perez JA, Maca-Meyer N, Flores C, Cabrera VM : Mitochondrial DNA affinities at the Atlantic fringe of Europe. Am J Phys Anthropol 2003; 120: 391–404.

Gnammankou D : African Slave Trade in Russia. Paris: UNESCO, 1988.

Sajantila A, Lahermo P, Anttinen T et al: Genes and languages in Europe – an analysis of mitochondrial lineages. Genome Res 1995; 5: 42–52.

Bermisheva M, Tambets K, Villems R, Khusnutdinova E : Diversity of mitochondrial DNA haplogroups in ethnic populations of the Volga–Ural region. Mol Biol (Mosk) 2002; 36: 990–1001.

Pliss L, Tambets K, Loogvali E-L et al: Mitochondrial DNA portrait of Latvians: towards the understanding of the genetic structure of Baltic-speaking populations. Ann Hum Genet 2006; 70: 439–458.

Malyarchuk BA, Derenko MV, Grzybowski T et al: Differentiation of mitochondrial DNA and Y chromosome in Russian populations. Hum Biol 2004; 76: 877–900.

Grzybowski T, Malyarchuk BA, Derenko MV, Perkova MA, Bednarek J, Wozniak M : Complex interactions of the Eastern and Western Slavic populations with other European groups as revealed by mitochondrial DNA analysis. Forensic Sci Int: Genetics 2007; 1: 141–147.

Malyarchuk BA, Grzybowski T, Derenko MV, Czarny J, Woniak M, Micicka-liwka D : Mitochondrial DNA variability in Poles and Russians. Ann Hum Genet 2002; 66: 261–283.

Malyarchuk BA, Grzybowski T, Derenko MV, Czarny J, Drobni K, Miscicka-Sliwka D : Mitochondrial DNA variability in Bosnians and Slovenians. Ann Hum Genet 2003; 67: 412–425.

Malyarchuk BA, Vanecek T, Perkova MA, Derenko MV, Sip M : Mitochondrial DNA variability in the Czech population, with application to the ethnic history of Slavs. Hum Biol 2006; 78: 681–696.

Malyarchuk BA, Perkova MA, Derenko MV, Vanecek T, Lazur J, Gomolcak P : Mitochondrial DNA variability in Slovaks, with application to the Roma origin. Ann Hum Genet 2008; 72: 228–240.

Richards MB, Macaulay VA, Hickey E et al: Tracing European founder lineages in the near eastern mtDNA pool. Am J Hum Genet 2000; 67: 1251–1276.

Malyarchuk BA, Czarny J : African DNA lineages in the mitochondrial gene pool of Europeans. Mol Biol (Mosk) 2005; 39: 703–709.

Casas MJ, Hagelberg E, Fregel R, Larruga JM, Gonzalez AM : Human mitochondrial DNA diversity in an archaeological site in al-Andalus: genetic impact of migrations from North Africa in medieval Spain. Am J Phys Anthropol 2006; 131: 539–551.

Andrews RM, Kubacka I, Chinnery PF, Lightowlers RN, Turnbull DM, Howell N : Reanalysis and revision of the Cambridge reference sequence for human mitochondrial DNA. Nat Genet 1999; 23: 147.

Torroni A, Rengo C, Guida V et al: Do the four clades of the mtDNA haplogroup L2 evolve at different rates? Am J Hum Genet 2001; 69: 1348–1356.

Cerny V, Salas A, Hájek M, aloudková M, Brdicka R : A bidirectional corridor in the Sahel–Sudan belt and the distinctive features of the Chad Basin populations: a history revealed by the mitochondrial DNA genome. Ann Hum Genet 2007; 71: 433–452.

Hünemeier T, Carvalho C, Marrero AR, Salzano FM, Pena SDJ, Bortolini MC : Niger-Congo speaking populations and the formation of the Brazilian gene pool: mtDNA and Y-chromosome data. Am J Phys Anthropol 2007; 133: 854–867.

Ruiz-Pesini E, Lott MT, Procaccio V et al: An enhanced MITOMAP with a global mtDNA mutational phylogeny. Nucleic Acids Res 2007; 35 (Database issue): D823–D828.

Bandelt HJ, Forster P, Rohl A : Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 1999; 16: 37–48.

Forster P, Harding R, Torroni A, Bandelt HJ : Origin and evolution of Native American mtDNA variation: a reappraisal. Am J Hum Genet 1996; 59: 935–945.

Saillard J, Forster P, Lynnerup N, Bandelt H-J, Norby S : MtDNA variation among Greenland Eskimos: the edge of the Beringian expansion. Am J Hum Genet 2000; 67: 718–726.

Mishmar D, Ruiz-Pesini E, Golik P et al: Natural selection shaped regional mtDNA variation in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100: 171–176.

Olivieri A, Achilli A, Pala M et al: The mtDNA legacy of the Levantine early upper Palaeolithic in Africa. Science 2006; 314: 1767–1770.

Torroni A, Achilli A, Macaulay V, Richards M, Bandelt H-J : Harvesting the fruit of the human mtDNA tree. Trends Genet 2006; 22: 339–345.

Richard C, Pennarun E, Kivisild T et al: An mtDNA perspective of French genetic variation. Ann Hum Biol 2007; 34: 68–79.

Derenko M, Malyarchuk B, Grzybowski T et al: Phylogeographic analysis of mitochondrial DNA in northern Asian populations. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 81: 1025–1041.

Herrnstadt C, Elson JL, Fahy E et al: Reduced median-network analysis of complete mitochondrial DNA coding-region sequences from the major African, Asian, and European haplogroups. Am J Hum Genet 2002; 70: 1152–1171.

Plaza S, Calafell F, Helal A et al: Joining the pillars of Hercules: mtDNA sequences show multidirectional gene flow in the western Mediterranean. Ann Hum Genet 2003; 67: 312–328.

Francalacci P, Bertranpetit J, Calafell F, Underhill PA : Sequence diversity of the control region of mitochondrial DNA in Tuscany and its implications for the peopling of Europe. Am J Phys Anthropol 1996; 100: 443–460.

Kivisild T, Shen P, Wall DP et al: The role of selection in the evolution of human mitochondrial genomes. Genetics 2006; 172: 373–387.

Gonzalez AM, Larruga JM, Abu-Amero KK, Shi Y, Pestano J, Cabrera VM : Mitochondrial lineage M1 traces an early human backflow to Africa. BMC Genomics 2007; 8: 223.

Alzualde A, Izagirre N, Alonso S et al: Insights into the ‘isolation’ of the Basques: mtDNA lineages from the historical site of Aldaieta (6th–7th centuries AD). Am J Phys Anthropol 2006; 130: 394–404.

Torroni A, Bandelt HJ, D'Urbano L et al: mtDNA analysis reveals a major late Paleolithic population expansion from southwestern to northeastern Europe. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 62: 1137–1152.

Achilli A, Rengo C, Battaglia V et al: Saami and Berbers – an unexpected mitochondrial DNA link. Am J Hum Genet 2005; 76: 883–886.

Gonzalez AM, Garcia O, Larruga JM, Cabrera VM : The mitochondrial lineage U8a reveals a Paleolithic settlement in the Basque country. BMC Genomics 2006; 7: 124.

Behar DM, Metspalu E, Kivisild T et al: The matrilineal ancestry of Ashkenazi Jewry: portrait of a recent founder event. Am J Hum Genet 2006; 78: 487–497.

Acknowledgements

We thank two anonymous reviewers for their useful comments. This study was supported by Far-East Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences grant 06-I-Ï1-032 and Program of Basic Research of Russian Academy of Sciences ‘Biodiversity and Dynamics of Gene Pools’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Malyarchuk, B., Derenko, M., Perkova, M. et al. Reconstructing the phylogeny of African mitochondrial DNA lineages in Slavs. Eur J Hum Genet 16, 1091–1096 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2008.70

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2008.70

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

60,000 years of interactions between Central and Eastern Africa documented by major African mitochondrial haplogroup L2

Scientific Reports (2015)

-

Divorcing the Late Upper Palaeolithic demographic histories of mtDNA haplogroups M1 and U6 in Africa

BMC Evolutionary Biology (2012)

-

Multiplex genotyping system for efficient inference of matrilineal genetic ancestry with continental resolution

Investigative Genetics (2011)