Abstract

Background:

Paracentesis for malignant ascites is usually performed as an in-patient procedure, with a median length of stay (LoS) of 3–5 days, with intermittent clamping of the drain due to a perceived risk of hypotension. In this study, we assessed the safety of free drainage and the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of daycase paracentesis.

Method:

Ovarian cancer admissions at Hammersmith Hospital between July and October 2009 were audited (Stage 1). A total of 21 patients (Stage 2) subsequently underwent paracentesis with free drainage of ascites without intermittent clamping (October 2010–January 2011). Finally, 13 patients (19 paracenteses, Stage 3), were drained as a daycase (May–December 2011).

Results:

Of 67 patients (Stage 1), 22% of admissions and 18% of bed-days were for paracentesis, with a median LoS of 4 days. In all, 81% of patients (Stage 2) drained completely without hypotension. Of four patients with hypotension, none was tachycardic or symptomatic. Daycase paracentesis achieved complete ascites drainage without complications, or the need for in-patient admission in 94.7% of cases (Stage 3), and cost £954 compared with £1473 for in-patient drainage.

Conclusions:

Free drainage of malignant ascites is safe. Daycase paracentesis is feasible, cost-effective and reduces hospital admissions, and potentially represents the standard of care for patients with malignant ascites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Malignant ascites is the accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity caused by an underlying cancer (Agarwal and Kaye, 2003). Around 15–50% of all cancer patients will develop malignant ascites (Ayantunde and Parsons, 2007). It is most commonly seen in ovarian, where it is present in 36% of women at the time of diagnosis of ovarian cancer (EOC), and is present in approximately 60% at the time of death (Sorbe and Frankendal, 1983). Other cancers associated with malignant ascites are primary peritoneal, endometrial, breast, pancreatic and gastrointestinal malignancies (Ayantunde and Parsons, 2007). The presence of large volume ascites causes abdominal discomfort, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, and deterioration in quality of life. Palliation of symptoms with minimal distress is therefore paramount.

In-patient paracentesis is the most commonly used procedure in over 85% of cases, which achieves prompt relief of symptoms (Macdonald et al, 2006; Keen et al, 2010). In-patient admission for paracentesis of malignant ascites utilises over 28 000 hospitals bed-days annually, and has a significant impact on healthcare resources and is onerous for patients (HESOnline, 2008). Malignant ascites re-accumulates in patients with disease progression. Diuretics have been used to diminish re-accumulation, with variable benefit and risk of dehydration and renal dysfunction (Ayantunde and Parsons, 2007). Other strategies for the management of recurrent ascites have included the use of peritoneovenous (PV) shunts, intraperitoneal (IP) interferon-alpha and tumour-necrosis factor (Rath et al, 1991; Hirte et al, 1997; White et al, 2011b). In addition, recent studies have demonstrated potential benefit from IP catumaxomab, a tri-functional antibody to CD3, EpCAM with a functional Fc domain and VEGF targeting with bevacizumab and aflibercept (Hu et al, 2005; Numnum et al, 2006; Hamilton et al, 2008; Kobold et al, 2009; Heiss et al, 2010; Gotlieb et al, 2011). However, PV shunts are associated with complications including pulmonary oedema, major vein thrombosis and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy in 38% of patients (White et al, 2011b). Catumaxomab leads to pyrexia, nausea and abdominal pain due to cytokine release in over 60% on patients, and VEGF inhibition is associated with fatal bowel perforation in a subset of patients (Kobold et al, 2009; Heiss et al, 2010; Gotlieb et al, 2011). The recent development of indwelling tunnelled catheters potentially offers patients with recurrent ascites, at short intervals, a safer alternative, albeit with the inconvenience, discomfort and infection risk of a long-term indwelling catheter (White et al, 2011a).

The Hospital Episode Statistics suggest an average length of in-patient stay (LoS) for paracentesis of 4 days (HESOnline, 2008). This is due to the common practice of intermittent clamping of drains, because of a perceived risk of hypotension with free drainage, based on historical experience with paracentesis for transudative ascites due to hypo-albuminaemia and portal hypertension in patients with liver cirrhosis. These patients frequently require intravenous fluid replacement, and many gastroenterology units routinely co-administer human albumin solution. Malignant ascites develops as a consequence of peritoneal carcinomatosis, portal vein compression and lymphatic invasion (Tan et al, 2006; Tamsma, 2007). Recent preclinical and clinical data have also identified a key role of VEGF and increased vascular permeability in the development of ascites, as also demonstrated by the efficacy of bevacizumab and aflibercept in some patients (Hu et al, 2005; Numnum et al, 2006; Tan et al, 2006; Tamsma, 2007; Hamilton et al, 2008). In view of the difference in the pathophysiology of malignant ascites, a recent study of 18 women (23 episodes of paracentesis) with ovarian cancer suggested that free drainage of malignant ascites was safe and did not cause significant hypotension (Decruze et al, 2010). Similarly, Gotlieb et al (1998) have previously shown that free drainage is associated with only modest (6 mm Hg) fall in systolic blood pressure (SBP), but no changes in diastolic BP, and is safe. Because in-patient admissions limit the quality of life of patients with advanced disease; daycase paracentesis if possible is a potentially preferable alternative. However, the attempts of Decruze et al (2010) to perform paracentesis as a daycase procedure was associated with a 44% admission rate due to incomplete drainage of ascites, whereas in another study in a hospice setting, daycase paracentesis achieved only partial fluid drainage (Stephenson and Gilbert, 2002).

Concerns over the risk of hypotension, the small size of the Decruze study, the lack of independent validation of their results and high admission or partial drainage rates continue to limit the adoption of daycase paracentesis clinically (Stephenson and Gilbert, 2002; Macdonald et al, 2006; Decruze et al, 2010).

To address these issues, we audited our in-patient bed utilisation for paracentesis, and re-assessed the safety of free drainage of ascites. Reasons for high admission rates owing to partial drainage in the previous study related to delays in drain insertion and slow fluid drainage. To eliminate the need for in-patient admission while retaining high rates of complete drainage, we evaluated the feasibility of daycase paracentesis, with radiological insertion of drains instead of junior doctors. We also determined the cost-effectiveness of such a strategy relative to in-patient paracentesis.

Method

This study was conducted in three stages.

Stage 1 – audit of admissions

An audit of all the 67 in-patient admissions (Stage 1) between July and October 2009, for ovarian cancer, to the Department of Oncology, Hammersmith Hospital, London, was performed to assess the proportion of in-patient resources utilised for ascitic drainage. Data on the reason for admission, LoS and whether patients were chemonaive, on chemotherapy, relapsing or in the terminal phase were collected from the oncology electronic patient database. For paracentesis, patients were marked for drainage using ultrasound guidance in radiology, and the drain was inserted on the medical ward by a junior doctor.

Stage 2 – safety of free drainage

A total of 21 consecutive patients with EOC requiring ascitic drainage between October 2010 and January 2011 were drained without intermittent clamping of the drain. The baseline characteristics of the patients (Stage 2) are shown in Table 1. Patients were admitted as in-patients, the drain insertion site marked by ultrasound in radiology, and the catheter was sited by a junior doctor on the ward. Following the drain insertion, catheters were left unclamped. The drain was re-clamped if the systolic blood pressure fell to <95 mm Hg or the patient was unwell.

A proforma (Supplementary Material 1) was used to prospectively record: date and time of admission; ultrasound marking for drainage and drain insertion; BP and heart rate prior to drain insertion, during drainage and hourly for 2 h following drain removal; and the total volume of ascites drained at specified time intervals. The renal function, albumin, platelet count and clotting prior to drain insertion were recorded. The following data was collected retrospectively from the medical and nursing notes: route of admission, LoS, stage, grade and histology of ovarian cancer, months since diagnosis, treatment history and the use of anti-hypertensives and anticoagulants.

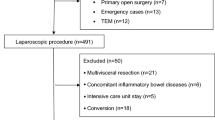

Stage 3 – feasibility and cost-effectiveness of daycase paracentesis

The feasibility of complete fluid drainage, without complication or the need for in-patient admission, as a daycase with radiological drain insertion, was evaluated in patients requiring non-emergency paracentesis (Supplementary Figure 1). Patients were eligible for daycase paracentesis if their performance status was 0–2, they were not taking warfarin, did not require hospital transport, were able to wait 2–7 days for drainage and had normal platelet counts and coagulation. If patients were on subcutaneous low-molecular weight heparin, the patient was asked to omit the dose the night before the procedure (Supplementary Material 2). All the patients received a Patient Information Sheet to explain the procedure (Supplementary Material 3). Patients were asked to complete a questionnaire following daycase paracentesis (Supplementary Material 4).

To enable complete drainage during working hours, the procedure was performed with ultrasound guidance prior to 1000 hours. Abdominal ultrasound was performed, and the largest locule of ascitic fluid was identified. The overlying skin was infiltrated with 1% lidocaine, a 2–3-mm incision was made and using the Seldinger technique, a 145-cm 035″ Fixed Core Curved Safe-T-J Wire Guide (3 mm) (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) was inserted and the needle exchanged for a 6-Fr Angiotech Skater drainage catheter (Angiotech, Vancouver, Canada). The catheter were sutured to the skin, connected to a Simpla Profile Night Bag (2000, ml) (Coloplast, Peterborough, UK) and left on free drainage.

No intravenous fluids were administered. Blood pressure and heart rate were assessed every 15 min in the radiology department for 1 h, then every 30 min for a second hour. After 2 h, the patient returned to the day unit. An armchair was made available for all patients and they were not required to lie flat. At 1600 hours, patients were reviewed, and if the patient had drained completely, the drain was removed and the patient is discharged home. If drainage was incomplete, or the patient became symptomatic, the patient was admitted. To assess the cost-effectiveness of daycase paracentesis, we estimated the difference in resources used between the standard in-patient paracentesis and the daycase paracentesis, based on the results of Stages 2 and 3 of this study, respectively. In-patient and daycase paracentesis differed in terms of length of hospital stay and the staff involved with the drain insertion. The cost of the drain was assumed to be constant, and therefore omitted for the cost comparison. Unit costs for these resources were obtained from the National Schedule of Reference Costs (Curtis, 2010; NHS Reference Costs , 2011).

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were analysed by using the Chi-square test and continuous variables by using Mann–Whitney U-test, with P<0.05 used to determine statistical significance. Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) were used to perform all analyses.

Results

Clinical and resource impact of paracentesis for malignant ascites

There were 67 admissions for 597 bed-days, for ovarian cancer, over the 4-month audit period (Stage 1). In all, 22% of admissions and 18% of bed-days were for ascitic drainage (Figure 1), with a median LoS for paracentesis of 4 days (range 1–26). Patients requiring ascitic drainage only, without any other procedures or investigations, had a median LoS of 3 days.

Safety of paracentesis with free ascitic drainage

A total of 21 paracenteses with free drainage of ascites were performed in 18 patients (Stage 2), between October 2010 and January 2011 (Table 1). The median age of women undergoing drainage was 64 years (range 54–84) (Table 1). Three had not received any prior treatment, including debulking surgery or chemotherapy. The average time from diagnosis was 24 months (0–98 months). Five of the patients had previously undergone ascitic drainage; the average length of time since OR from the previous paracentesis was 3 months (1–10 months). Overall, 13 of the patients were on antihypertensive medication and 10 on anticoagulants.

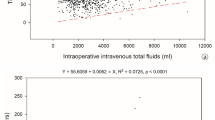

The average volume of ascites drained was 4500 ml (range 750–8400 ml). On average, 50% of the total ascitic fluid volume drained in 3 h, 70% in 6 h and 75% in 8 h (Figure 2). The median LoS for all patients undergoing drainage of malignant ascites was 7 days. Those admitted solely for drainage of ascites had a median LoS of 3 days (range 1–13), but if admitted via A&E (Accident and Emergency), the median LoS increased to 5 days (Table 2).

Of the 21 episodes of paracenteses with free drainage, 5 were clamped. One ascitic drain was accidentally clamped after 2 h. The patient was well and not hypotensive. In four patients (19%; 95% CI 2–36%), the drain was clamped due to a fall in SBP <95 mm Hg (Figure 3, Supplementary Table 1). However, none of the patients felt unwell or had a compensatory tachycardia, suggesting that the fall in BP was in part a re-normalisation of the BP, with the relief of abdominal discomfort and anxiety (Figure 3). None of these four patients subsequently developed renal dysfunction (a rise in creatinine >25 μmol) as a result of their ascites drainage. No individual patient characteristic predicted for the development of asymptomatic hypotension, in particular, a low pre-procedure BP did not predict for the development of asymptomatic hypotension.

Feasibility of daycase paracentesis

Between May and December 2011, 19 paracenteses were performed as a daycase (Stage 3), on 15 occasions in 11 patients with EOC, thrice in a patient with bladder cancer and once in patient with stomach cancer (Table 1). Eighteen out of nineteen paracenteses (94.6%; 95% CI 74–100%) were to dryness as a daycase. Only one patient was admitted because the ascitic drain was placed late in the day, preventing adequate drainage by the close of day. None of the patients developed hypotension, nor any other complications. Of patients who had previously undergone ascitic drainage as an in-patient, 71% (5 of 7) favoured daycase over in-patient paracentesis, and all 5 of 5 patients who had recurrent ascites consented to further daycase paracentesis.

Comparative costs of daycase vs in-patient paracentesis

We calculated the cost of in-patient paracentesis with free drainage based on our results from Stage 2 with a median LoS of 3 days, and for daycase paracentesis based on Stage 3 of the study. The cost of in-patient paracentesis was £1473 compared with £954 for daycase paracentesis, and suggests a cost saving of at least £519 per episode with a daycase procedure (Table 3).

Discussion

Paracentesis is a simple, low-risk procedure that provides rapid symptomatic relief from malignant ascites. The current practice of in-patient paracentesis is onerous for patients and consumes significant healthcare resources. Our study confirms the safety of free drainage of malignant ascites, and further demonstrates that in contrast to published studies, complete drainage can be achieved in a daycase setting in over 94% of patients, with radiological insertion of drains. The ability to perform complete paracentesis as an out-patient, within 6–8 h, and with minimal nursing intervention represents a significant improvement. It avoids lengthy hospital admission, improves the quality of life in palliative patients, with savings of over £500 per patient.

Our ability to achieve >95% success rate with daycase paracentesis compared with the study by Decruze et al (2010) is likely to relate to planned radiological insertion of drains, minimising both delays associated with drain insertion by junior doctors, and a reduction in failed attempts at drain insertion (Decruze et al, 2010). The drains used in our study were 6 Fr, which is larger than commonly used Bannano catheters, which is likely to have also expedited the rate of fluid drainage. Drain insertion by radiologist also has the advantage of consistency of the service over time compared with fluctuations that are inherent with changes in junior doctors on rotational attachments. However, provided that the drain is sited by a competent non-radiologist under image guidance, and within protected times early in the working day, the success of such a service should be reproducible.

Radiological drain insertion is often perceived as a costly option for paracentesis. However, our data indicate that overall there is a saving of approximately £519, with daycase compared with in-patient paracentesis. Similarly, an independent cost analysis reviewed by NICE costed in-patient ascitic drainage at £3145, PleureX drains at £2466 and daycase paracentesis at £1456 (White et al, 2011a). The cost savings of a daycase paracentesis service therefore range between £519 and £1689 relative to in-patient drainage. Given that paracentesis accounted for more than 28 000 bed-days in hospitals in England during 2007–2008, if implemented nationally, daycase paracentesis has the potential to save the NHS between 18 000 bed-days and £4–14 million per annum.

Although we have only included good-performance-status patients in the daycase service so far, our preliminary study suggests that patients with a poorer performance status are no more likely to experience haemodynamic compromise. The main limitation to this study is that most of the patients included in Stage 3 are ovarian cancer patients. However, of the few non-gynaecological patients included in the study, we saw no complications. The practicalities of hospital transport and day-unit capacity is currently the major obstacle locally preventing our ability to offer all eligible patients the option of daycase paracentesis.

The recent positive review of PleureX catheters compared with in-patient paracentesis urgently raises the issue of the best strategy for selecting patients for these three alternatives (White et al, 2011a). Although there is a role for long-term indwelling ascitic drains, such as the commonly used Pleurex and Rocket catheters, we feel that the majority of patients do not require sufficiently frequent drainage to necessitate an indwelling drain. Of the 29 patients with ovarian cancer in Stages 2 and 3, only 6 (21%) had been drained in the previous 17 months (Supplementary Table 2). This demonstrates that the majority of ovarian cancer patients are drained for platinum-sensitive relapse, and that daycase paracentesis is the preferred method for drainage. In contrast, in platinum-resistant patients, with recurrence ascites, long-term drains may be considered.

In summary, our results confirm the safety of free ascitic drainage and demonstrate the feasibility of daycase paracentesis with complete fluid drainage in over 94% of patients with radiological catheter insertion. Coupled with it’s cost-effectiveness, our results suggest that daycase paracentesis can potentially be considered the primary treatment modality for the management of malignant ascites, especially with ovarian cancer and good performance status, and should be an option more widely available to patients.

Change history

18 August 2012

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Agarwal R, Kaye SB (2003) Ovarian cancer: strategies for overcoming resistance to chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 3: 502–516

Ayantunde AA, Parsons SL (2007) Pattern and prognostic factors in patients with malignant ascites: a retrospective study. Ann Oncol 18: 945–949

Curtis L (2010) Unit Costs of Health & Social Care. Unit PSSR: Canterbury, Kent

Decruze SB, Macdonald R, Smith G, Herod JJ (2010) Paracentesis in ovarian cancer: a study of the physiology during free drainage of ascites. J Palliat Med 13: 251–254

Gotlieb WH, Amant F, Advani S, Goswami C, Hirte H, Provencher D, Somani N, Yamada SD, Tamby JF, Vergote I (2011) Intravenous aflibercept for treatment of recurrent symptomatic malignant ascites in patients with advanced ovarian cancer: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet Oncol 13: 154–162

Gotlieb WH, Feldman B, Feldman-Moran O, Zmira N, Kreizer D, Segal Y, Elran E, Ben-Baruch G (1998) Intraperitoneal pressures and clinical parameters of total paracentesis for palliation of symptomatic ascites in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 71: 381–385

Hamilton CA, Maxwell GL, Chernofsky MR, Bernstein SA, Farley JH, Rose GS (2008) Intraperitoneal bevacizumab for the palliation of malignant ascites in refractory ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 111: 530–532

Heiss MM, Murawa P, Koralewski P, Kutarska E, Kolesnik OO, Ivanchenko VV, Dudnichenko AS, Aleknaviciene B, Razbadauskas A, Gore M, Ganea-Motan E, Ciuleanu T, Wimberger P, Schmittel A, Schmalfeldt B, Burges A, Bokemeyer C, Lindhofer H, Lahr A, Parsons SL (2010) The trifunctional antibody catumaxomab for the treatment of malignant ascites due to epithelial cancer: results of a prospective randomized phase II/III trial. Int J Cancer 127: 2209–2221

HESOnline (2008) Hospital episode statistics: main procedures and interventions. Available at http://www.hesonline.nhs.uk/

Hirte HW, Miller D, Tonkin K, Findlay B, Capstick V, Murphy J, Buckman R, Carmichael J, Levine M, Hill W (1997) A randomized trial of paracentesis plus intraperitoneal tumor necrosis factor-alpha versus paracentesis alone in patients with symptomatic ascites from recurrent ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 64: 80–87

Hu L, Hofmann J, Holash J, Yancopoulos GD, Sood AK, Jaffe RB (2005) Vascular endothelial growth factor trap combined with paclitaxel strikingly inhibits tumor and ascites, prolonging survival in a human ovarian cancer model. Clin Cancer Res 11: 6966–6971

Keen A, Fitzgerald D, Bryant A, Dickinson HO (2010) Management of drainage for malignant ascites in gynaecological cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. CD007794

Kobold S, Hegewisch-Becker S, Oechsle K, Jordan K, Bokemeyer C, Atanackovic D (2009) Intraperitoneal VEGF inhibition using bevacizumab: a potential approach for the symptomatic treatment of malignant ascites? Oncologist 14: 1242–1251

Macdonald R, Kirwan J, Roberts S, Gray D, Allsopp L, Green J (2006) Ovarian cancer and ascites: a questionnaire on current management in the United kingdom. J Palliat Med 9: 1264–1270

NHS reference costs 2009–10 (2011) Health Do (ed). Available at http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_123459

Numnum TM, Rocconi RP, Whitworth J, Barnes MN (2006) The use of bevacizumab to palliate symptomatic ascites in patients with refractory ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 102: 425–428

Rath U, Kaufmann M, Schmid H, Hofmann J, Wiedenmann B, Kist A, Kempeni J, Schlick E, Bastert G, Kommerell B (1991) Effect of intraperitoneal recombinant human tumour necrosis factor alpha on malignant ascites. Eur J Cancer 27: 121–125

Sorbe B, Frankendal B (1983) Prognostic importance of ascites in ovarian carcinoma. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 62: 415–418

Stephenson J, Gilbert J (2002) The development of clinical guidelines on paracentesis for ascites related to malignancy. Palliat Med 16: 213–218

Tamsma J (2007) The pathogenesis of malignant ascites. Cancer Treat Res 134: 109–118

Tan DS, Agarwal R, Kaye SB (2006) Mechanisms of transcoelomic metastasis in ovarian cancer. Lancet Oncol 7: 925–934

White J, Carolan-Rees G, Dale M (2011a) External Assessment Centre Report: PleureX indwelling peritoneal catheter for vacuum assisted drainage of recurrent malignant ascites at home. Available at http://guidance.nice.org.uk/MT/131/Consultation/ExternalAssessment/pdf/English

White MA, Agle SC, Padia RK, Zervos EE (2011b) Denver peritoneovenous shunts for the management of malignant ascites: a review of the literature in the post LeVeen Era. Am Surg 77: 1070–1075

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a grant from the Imperial Healthcare Charity. RA is funded by a Clinician Scientist Fellowship from Cancer Research UK. The study was also supported by the Imperial College Biomedical Research Centre, Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre and Ovarian Cancer Action. We are grateful to Rosemary Fisher for her advice on the manuscript.

Author contributions

RA conceived the idea of the project and implementation of all stages. Data collection, analysis and data interpretation were done by RB and ND for Stage 1, VH, SN and HKL for Stage 2, and VH, HM, RS and MT for Stage 3 of the project. SM was responsible for the radiological drain insertions, and CEU for the implementation of Stage 3. HG and SB were involved in care of patients. All authors contributed to interpretation and writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Harding, V., Fenu, E., Medani, H. et al. Safety, cost-effectiveness and feasibility of daycase paracentesis in the management of malignant ascites with a focus on ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer 107, 925–930 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.343

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.343

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Continuous low flow ascites drainage through the urinary bladder via the Alfapump system in palliative patients with malignant ascites

BMC Palliative Care (2019)

-

HE4 level in ascites may assess the ovarian cancer chemotherapeutic effect

Journal of Ovarian Research (2018)

-

Palliativmedizinische Konzepte beim Ovarialkarzinom

Der Gynäkologe (2017)

-

Automated low flow pump system for the treatment of refractory ascites: a single-center experience

Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery (2015)

-

A survey of treatment approaches of malignant ascites in Germany and Austria

Supportive Care in Cancer (2015)