Abstract

The spectral dependence of light absorption by atmospheric particulate matter has major implications for air quality and climate forcing, but remains uncertain especially in tropical areas with extensive biomass burning. In the September-October 2007 biomass-burning season in Santa Cruz, Bolivia, we studied light absorbing (chromophoric) organic or “brown” carbon (BrC) with surface and space-based remote sensing. We found that BrC has negligible absorption at visible wavelengths, but significant absorption and strong spectral dependence at UV wavelengths. Using the ground-based inversion of column effective imaginary refractive index in the range 305–368 nm, we quantified a strong spectral dependence of absorption by BrC in the UV and diminished ultraviolet B (UV-B) radiation reaching the surface. Reduced UV-B means less erythema, plant damage, and slower photolysis rates. We use a photochemical box model to show that relative to black carbon (BC) alone, the combined optical properties of BrC and BC slow the net rate of production of ozone by up to 18% and lead to reduced concentrations of radicals OH, HO2, and RO2 by up to 17%, 15%, and 14%, respectively. The optical properties of BrC aerosol change in subtle ways the generally adverse effects of smoke from biomass burning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biomass burning emits large amounts of black carbon (BC) and organic carbon (OC) particles into the atmosphere. This has profound effects on Earth’s radiation budget and on atmospheric photochemistry. Most current aerosol models treat all OC from biomass burning as purely scattering, thus underestimating heating effect of the total carbon (OC + BC), the primary absorbing component of carbonaceous aerosols1. However, recent studies2,3,4,5,6 suggest that the light absorbing component of OC known as “brown carbon” (BrC) is capable of enhancing total absorption efficiency of OC, altering direct radiative forcing (DRF) at top of the atmosphere from negative to positive6,7. Our ‘assumed BrC’ is defined by the retrieved total absorption minus the retrieved absorption by the BC component. Measuring BrC absorption is also essential due to its effect on photolysis rates8,9 and solar UV radiation reaching the surface10,11,12 with important implications for plant growth13,14 and human health15.

Field measurements of light absorption by aerosols (defined as column effective imaginary part of the complex refractive index, k) in the visible and near-infrared (NIR) wavelengths (440, 670, 870, and 1020 nm) are available from ~400 global locations of the Aerosol Robotic Network (AERONET)16,17. Schuster et al.18 used those measurements to infer the column-averaged mass density and mass absorption efficiency (MAE) of BC at selected AERONET sites. Arola et al.19 advanced the method of Schuster et al.18 to infer both BC and BrC volume fractions from the AERONET inversions that show enhanced values of k at 440 nm relative to the red and NIR wavelengths. The spectral dependence of BrC absorption can vary strongly depending on the type of aerosol emissions (fossil fuel combustion versus biomass burning), as well as physical-chemical transformation (primary versus secondary organic aerosols)6,20. As a result, the 440 nm wavelength does not have enough sensitivity to properly detect some types of BrC. We combine AERONET almucantar inversions in the visible–NIR wavelengths with diffuse and direct surface irradiance measurements from UV Multifilter Rotating Shadowband Radiometer (UV-MFRSR)11,21 to estimate the BrC column mass density; this is not possible from standalone AERONET inversions. Previous measurements of column aerosol absorption in UV wavelengths have been conducted in urban/suburban locations21,22,23. We present the first measurements of the spectral dependence of k for smoke down to the biologically active, UV-B wavelengths (~305 nm) to estimate the MAE of BrC, the BrC/BC column mass density ratio, and effects on tropospheric ozone photochemistry.

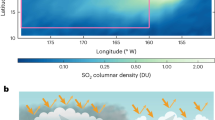

To measure UV absorption by smoke, we conducted a field campaign in Santa Cruz, Bolivia in September 2007, the month of peak carbonaceous aerosol production in South America from agricultural biomass burning in the Amazon Basin24,25, using UV-MFRSR irradiance measurements. The total (scattering and absorption) aerosol optical depth measured by AERONET at 440 nm ranged from 0.74 to 2.27. Satellite measurements of UV aerosol absorption optical depth (AAOD) from Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) on board NASA’s Earth Observing System Aura satellite26,27 (see Supplementary Section 2 for details) clearly show elevated AAOD values over Santa Cruz in September 2007 (Fig. 1a). The flow of smoke was blocked by the Andes Mountains (see the true color satellite imagery in Fig. 1b), so smoke accumulated over the area to the east of the mountain range. This increased the fraction of aged brown secondary organic aerosol, with less absorption at visible wavelengths but stronger absorption in the UV5,28. Biomass burning in the tropics also produces elevated levels of tropospheric ozone, a secondary pollutant resulting from photochemical reactions involving nitrogen oxides (NOx = NO + NO2) and volatile organic compounds (VOC) in the presence of sunlight29,30. Tropospheric ozone negatively affects agricultural crops, the human respiratory system, and is the main culprit responsible for photochemical smog.

Distribution of biomass burning and resultant smoke over South America.

(a) Satellite map of monthly mean aerosol absorption optical depth (AAOD = AOD*(1-SSA)) at 388 nm for September 2007 derived using two-channel OMAERUV aerosol algorithm applied to the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) on board NASA’s Aura satellite. The OMAERUV aerosol dataset is available from NASA’s Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center (http://disc.sci.gsfc.nasa.gov/uui/datasets/OMAERUV_V003/summary?keywords=%2522Aura%20OMI%2522#prod-summary). This plot was created using the IDL (Interactive Data Language) software version 7.1.1. The URL link to access the IDL software is http://www.harrisgeospatial.com/ProductsandSolutions/GeospatialProducts/IDL/Language.aspx. (b) MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) true-color image captured on 9 September 2007 over the same region showing active fire locations (marked in red) and a thick blanket of smoke stretching from the Amazon to Argentina; the image was obtained from NASA’s Earth Observatory website54. A solid black triangle shows the location of Santa Cruz.

Results

Retrieval and evaluation of spectral dependence of smoke absorption

Figure 2a shows joint UV-MFRSR and AERONET retrievals of spectral k (see details in Supplementary Section 1). Our assumptions about mixing state, size distribution, and sphericity are fully consistent with the standard AERONET inversions17,31. We only use sphericity retrievals by AERONET exceeding 95% to justify the sphericity assumption. Both retrievals agree at 440 nm. The flat spectral dependence of k in the visible–NIR region is consistent with a “BC only absorption” assumption18,32. However, this hypothesis (see the extrapolated red line in Fig. 2a) is grossly inconsistent with the observed enhanced values of k in the UV. We postulate that the enhanced k values in the UV are a manifestation of the presence of a selectively UV absorbing BrC component of the aged carbonaceous aerosols from tropical forest burning5,33.

Spectral dependence of smoke aerosol absorption parameters derived from ground-based and satellite (OMI) retrievals during the field campaign in Santa Cruz, Bolivia in September-October 2007.

(a) Imaginary part of the column effective refractive index (k), (b) Single scattering albedo (SSA), (c) Aerosol absorption optical depth (AAOD = AOD*(1-SSA)). Retrievals are from UV-MFRSR (blue symbols), Vis–NIR AERONET (red symbols), and satellite OMI UV (green symbols). All retrievals are shown as box-whisker plots. Boxes are the interquartile range (IQR; 25 to 75 percentiles) and whiskers are stretched to the maximum and minimum within 1.5 times the IQR. The circles show the outliers. The solid red line in a shows the theoretically calculated campaign–average k assuming that BC is the only absorbing component. The error bars in b and c for OMI-retrieved SSA and AAOD (±0.03 for SSA and ±30% for AAOD) are shown as thin vertical lines exceed the whisker’s range.

To compare with OMI retrievals at 354 nm and 388 nm, we convert the UV-MFRSR-retrieved k into single scattering albedo (SSA) assuming AERONET inferred aerosol size distribution and spherical aerosol shape (AERONET spherical particles fraction > 95%) (Fig. 2b). The average UV-MFRSR SSA at 388 nm (linearly interpolated from retrievals at 368 nm and 440 nm) is slightly smaller than the OMI values, but within the 0.03 error typically assumed in OMI retrievals27. Fig. 2c shows derived spectral dependence of AAOD, which describes the total column smoke absorption optical depth due to both BC and BrC. The UV-MFRSR AAOD values agree well with AERONET AAOD at 440 nm and are within the ±30% error bar of the OMI-retrieved AAOD at UV-A wavelengths (Fig. 2c).

Similarly to the Angstrom Exponent (AE), which characterizes spectral dependence of AOD parameterized by power law, the absorption Angstrom Exponent (AAE) characterizes spectral dependence of AAOD = AOD*(1-SSA). For smoke aerosols, there is no single power law parameterization describing AAOD spectral dependence from UV to the NIR wavelengths. This results in spectrally dependent values of AAE. The UV-MFRSR derived AAE in UV wavelengths (~3.0 in the range 305–368 nm) agrees well with the OMI assumed AAE (~2.8 between 354 nm and 388 nm)34, which is significantly larger than the AAE in the visible–NIR wavelengths (AAE ~1.1 ± 0.3 for BC only absorption)35. This confirms the general assumption that smoke absorption in the visible–NIR wavelengths is dominated by BC component, while in the UV band absorption by BrC plays a significant role. We calculated AAEBrC by fitting a power law equation to the retrieved values of BrC absorbing optical depth (AAODBrC) from 305–368 nm. AAODBrC(λ) = total AAOD(λ) −AAODBC(λ) (See Table 1) where AAODBC is calculated assuming a constant refractive index from the AERONET retrievals at 440 nm. Our estimated AAEBrC falls within the range of the previous measurements, e.g. 5.1 ± 1.9 in Indo-Gangetic Plain36, 5.83 ± 0.51 in Beijing37, and slightly less than the higher values of 6–7 measured for humic-like substances in the Amazon basin38. This confirms the spectral dependence that we believe describes South American forest burning BrC optical properties in chemistry- and aerosol- transport models.

Estimating the BrC volume fraction and BrC/BC ratio

Arola et al.19 inferred BrC volume fraction (fBrC) in addition to BC volume fraction (fBC), but only for cases when the AERONET retrieved k value at 440 nm is enhanced, compared to the longer visible and NIR wavelengths (670–1020 nm). This enhancement was attributed to additional BrC absorption and allowed the calculation of fBrC using a priori information about the complex refractive index of BrC from previous measurements. The method uses Maxwell-Garnett (MG) mixing rule assuming an internal mixture of BC and BrC embedded in non-absorbing host. The assumed refractive indices for these components are given in Arola et al.19. Our measurements show no evidence of enhanced BrC absorption at visible wavelengths (i.e., insignificant k enhancements at 440 nm compared to longer wavelengths, Fig. 2a), but significantly higher k in UV. Therefore, we advance the approach of Arola et al.19 to estimate fBrC using enhanced k values at a longer UV-A wavelength (i.e., 368 nm) which is not available from AERONET inversions. We also reduce the lower limit of the a priori BrC imaginary refractive index at 368 nm, kBrC-368 = 0.025, from recent smoke chamber experiments6. The upper limit on kBrC-368 = 0.14 is assumed from laboratory measurements of more absorbing African smoke samples2 (see Supplementary Fig. S1). Consequently, we calculate a range of values of fBrC from ~0.05 (using upper limit of kBrC-368)2 to ~0.27 (using lower limit of kBrC-368)6. We have verified low sensitivity of fBrC to the relative humidity by varying the real part of the refractive index (n) of host39. For instance, changing n by 10% would modify the BrC volume fraction by less than 2%. Assuming BrC mass density40 of 1.2 g/cm3, we estimate the range of BrC column mass densities from ~11 to 61 mg/m2, where the higher limit corresponds to the assumed lower limit of kBrC6 typical for Amazon forest burning smoke (see Methods section for details).

The inferred BrC/BC column mass density ratio ranges from 1.7 to 9.5 (see Supplementary Table S1). Previous studies have reported OC/BC ratios ranging from 4.3 to 12.5 for tropical forests, 8.3 to 16.7 for the Cerrado (South American savanna), and 12.5 to 33.3 for boreal forests41. These ratios are larger than our measured BrC/BC ratios because total OC is composed of absorbing (BrC) and non-absorbing OC. Thus, the ratio of BrC to BC is expected to be smaller than the ratio of total OC to BC. The primary sources of aged smoke in Santa Cruz are Cerrado and Amazon basin tropical forest burning, which is done for the purpose of clearing land for agricultural use, and the burning of crop residue after harvesting on existing agricultural land42. The highest smoke concentrations measured downwind at Santa Cruz are likely from tropical forest burning42. Our maximum estimated BrC/BC ratio (~9.5 using lower limit of kBrC values from Saleh et al.6) is consistent with the previous measurements for tropical forest and Cerrado burning. The lower limit of BrC/BC (~1.7) was obtained by assuming the upper limit of kBrC-368 from laboratory measurements of African savanna smoke samples collected on filters during the Southern African Regional Science Initiative (SAFARI 2000)2. A good agreement is found between BrC/BC and the OC/BC ratio (1.7) measured from agricultural land41.

Enhanced BrC spectral absorption in UV

Previous measurements2,6 of spectral absorption in the UV do not extend to biologically important wavelengths shorter than 350 nm. We use BrC volume fraction derived at 368 nm to infer spectral dependence of kBrC at shorter, more biologically active UV-B wavelengths down to 305 nm (Fig. 3). Specifically, we partitioned the retrieved kret into its kBrC and kBC components assuming that the smoke layer can be represented by a mixture of BC and BrC embedded into a non-absorbing host. The partitioning is carried out by applying the MG mixing rule to express the measured effective imaginary refractive index (kret), in terms of the volume fractions of BC (fBC) and BrC (fBrC) and their complex refractive indices (kBC and kBrC). The real part of the refractive index for the non-absorbing host, BC, and BrC is assumed to be spectrally constant as in Arola et al.19 Following this approach, kBrC values at 305, 311, 317, 325, and 332 nm are calculated by fitting the retrieved spectral kret using the MG mixing rule with the previously calculated and spectrally independent fBC, fBrC, and kBC (see Methods for details). The calculated spectral dependence of kBrC in the UV-B (characterized by the power exponent, w = 5.4–5.7) is significantly stronger than previous laboratory estimates, e.g. by Kirchstetter et al.2 (w = 3.9) and smoke chamber experiments by Saleh et al.6 (w = 1.6) (see Fig. 3). Thus, our measurements show that BrC in aged Amazonian smoke absorbs UV solar radiation with stronger spectral dependence than previously reported. This result has important implications for tropospheric photochemistry and biological effects of UV-B as discussed next.

The inferred spectral dependence of BrC imaginary refractive index (kBrC) in UV (blue circles with 20% error bars).

Black circles show the upper limit for kBrC-368 values derived from African savanna burning samples (10% uncertainty)2. Lower limit of kBrC-368 parameterization (green dashed lines) is based on smoke chamber experiments6 showing low spectral dependence (w = 1.6). The shaded area shows the variability range in our inferred kBrC in the UV wavelengths. We inferred much larger spectral dependence (w ~ 5.4–5.7) in the UV-B than previously reported (~1.6–4) in longer UV and visible wavelengths2,6.

We further convert our calculated AAOD for BrC (AAODBrC) and column mass density for BrC into specific mass absorption efficiency for BrC (MAEBrC) in the UV wavelengths (Table 1). MAEBrC is a useful parameter to compare with laboratory measurements and can be directly used in aerosol transport models. It has not been previously measured in the field under smoky conditions. The derived MAEBrC spectral dependence for smoke shows a strong increase at the shorter UV-B wavelengths similarly to those previously measured in anthropogenic aerosols43. The maximum and minimum values of MAEBrC (Table 1) are associated with the assumed range of kBrC-3682,6. Our minimum values (MAEBrC = 0.9–2.9 m2/g) are comparable with the previous measurements of low absorbing organic compounds in smoke from different locations, such as Alaska44, Siberia44, Indo-Gangetic Plain45, Beijing37, Colorado4, and Amazon basin38. Our maximum values (MAEBrC ~5–16 m2/g) are consistent with previous measurements for more absorbing organic aerosols originated from urban pollution43 and savanna burning2. The different ranges of MAEBrC for different wavelengths (See Table 1) suggest that BrC absorption should be treated regionally in chemical transport models. The upper limits of MAEBrC ranges should be used in areas where there is savannah burning. The lower limits of MAEBrC ranges should be used in areas where BrC is expected to be less absorbing. For Santa Cruz, the lower limits are more appropriate.

BrC absorption effect on surface UV and photochemistry

Excessive exposure to UV-B radiation causes damage to the eyes, suppression of the immune system, photoaging, and skin cancer15,46. There is also mounting evidence that it alters plant development and growth13,14. Under unpolluted and clear sky conditions, the levels of surface UV are high in Santa Cruz because of low overhead ozone and low solar zenith angles. Thus, the enhanced absorption of BrC at the most damaging UV-B wavelengths might play a role as a natural sunscreen. To quantify the specific spectral reduction of the surface UV due to absorption by BrC, we performed radiative transfer simulations of the spectral surface UV with and without BrC absorption. Figure 4 shows that the effect of BrC absorption causes an additional 20–25% reduction at the most damaging UV-B wavelengths reaching the surface (i.e., 305 nm) compared to the BC only (spectrally flat) absorption. This previously unaccounted reduction in surface UV-B irradiance is important for health risk assessments15,46 and estimating UV-B effects on crop yield13,14. Unaccounted absorption by BrC can also explain the positive bias in satellite derived surface UV-B compared to ground-based measurements11,47. The BrC absorption effect is smaller at longer UV-A wavelengths (~10% reduction at 320–330 nm).

Enhanced BrC absorption causes 20% decrease in the most damaging short wavelength surface UV-B irradiance (305–320 nm)

. Box-whisker plots show the relative difference [%] between our measured surface spectral UV (BC plus BrC absorption) and model (assuming BC only) surface UV: (UVmeas−UVBC)/UVBC × 100%. Red circles show independent model estimates using different LibRadtran (http://www.libradtran.org) RTM for the fixed SZA (45°) and ozone column amounts (272 DU).

The stronger absorption of BrC at UV-B wavelengths affects the atmospheric photochemistry. Dickerson et al.8 and other studies48,49 show that carbonaceous aerosols reduce the photolysis rate of NO2 (JNO2) responsible for ozone production by 10–30%. In extreme cases, JNO2 is reduced by 70% near the ground, while it is increased by 40% above the smoke layer due to aerosol backscattering50. Yet, these studies48,49,50 did not have the information necessary to discriminate between BC and BrC absorption. Our measurements allow us to isolate the effect of BrC absorption on photolysis rates (see Supplementary Fig. S2 for details) and ozone production using a radiative transfer model and a chemical box model (see Supplementary Section 3 and 4 for details). The enhanced absorption of BrC at the UV-B wavelengths around 308 nm (Fig. 3) decreases the photolysis rate of O3 (JO3) linked to the OH production by ~25% at the surface relative to BC only absorption (Fig. 5). But smaller absorption at longer UV wavelength (390 nm) decreases JNO2 linked to the ozone production mechanism by only 10%. Photolysis of carbonyls such as aldehydes is also inhibited by BrC, and this slows production of radicals OH, HO2, and RO2. Our box chemical model runs considering all major species subject to rapid photolysis (e.g., HCHO, CH3CHO, CH3OOH, HONO, H2O2, CHOCHO, CH3COCHO, CH3COONO2) reveal that the optical effects of BrC inhibit net surface and lower tropospheric ozone production by up to 18% (see Supplementary Fig. S3b). A recent study51 also reports that the absorption of BrC decreases OH concentration in South America in September by up to 35%. The reduced ozone and VOC photolysis rates due to BrC reduce concentrations of radicals OH, HO2, and RO2 by up to 17%, 15%, and 14%, respectively (see Supplementary Fig. S4), which in turn, produces less surface ozone. The reduction in the HOx (OH + HO2) and RO2 concentration also decreases the rate of removal of many other trace gases.

Modeling the impact of BrC absorption on the rate of tropospheric ozone production.

The vertical profiles show relative differences [%] in photolysis rates for NO2 (JNO2: dotted line) and ozone to O(1D) (JO3: dashed line) due to enhanced BrC UV absorption for different SZAs using a radiative transfer model. We assumed a homogeneously distributed smoke layer below 3 km as measured by space-based lidar. The ozone loss mechanism linked to JO3 is more significantly reduced than the production mechanism linked to JNO2. Input kret values for calculating photolysis rates are described in Supplementary Table S2.

Discussion

The combination of surface and space-based remote sensing of aerosol optical properties shows that biomass burning of the Cerrado, Amazonian forest, and agricultural lands in South America generates substantial amounts of light absorbing “brown carbon”, BrC. For the first time we have characterized the wavelength dependence of BrC absorption at the shortest and most biologically and chemically active UV-B wavelengths reaching Earth’s surface under aged biomass burning smoke conditions. The estimated optical properties of this BrC differ significantly from the optical models of BC or OC currently assumed in chemical- and aerosol-transport models. While the strong absorption of UV-B radiation seen for BrC can ameliorate some of the adverse health effects of smoke, biomass burning aerosols remain major environmental and health hazards52.

Our estimated range of the column volume fraction of BrC is 0.05 to 0.27 and of its column mass density is ~11 to 61 mg/m2. The best estimate is likely close to the upper limit because the lower limit represents more absorbing BrC (therefore, lower mass) from high temperature burn conditions in southern Africa savanna. The mass absorption efficiencies of BrC are largest at 305 nm, but vary significantly (e.g., 2.9 to 16.1 m2/g) due to variability in BrC column effective imaginary refractive index, kBrC. Regardless of this uncertainty in absolute values of kBrC, we were able to constrain its spectral dependence with improved accuracy. The best fit to the spectral dependence of kBrC in UV wavelengths is the power-law with retrieved exponent of 5.4 to 5.7.

Our derived total (BC + BrC) absorption Angstrom Exponent (AAE) in UV wavelengths (~3.0 in the range 305–368 nm) agrees well with the OMI assumed AAE (~2.8 between 354 nm and 388 nm)34, validating this a-priori assumption regarding k spectral dependence for smoke aerosols.

The primary difference between BrC and BC is the strong spectral dependence of the absorption of UV radiation by BrC. In comparison to BC alone, the combination of BC and BrC strongly decreases surface UV-B actinic flux, photolysis rates, and the rates of production of radicals ROx (ROx = OH+HO2+RO2+RO) and O3. Although a complex and nonlinear relationship exists with respect to concentrations of nitrogen oxide precursors, the observed optical properties of BrC reduce the rate of ozone production by up to ~18% over the full range of possible NOx values, from 100 ppb near the fires to 5 ppb well downwind of the fires. Radicals are also produced more slowly, and the lower concentrations of ROx mean longer lifetimes for ozone and its precursors (NOx and VOCs). This could lead to greater ozone concentrations downwind. The net impact will depend on the rate of dispersion and non-linear photochemistry including the speciation of VOCs. Future studies should include sufficient ambient measurements to initialize and constrain a 3-D chemical transport model.

Methods

Our field measurements of BrC and BC aerosol absorption are based on retrievals of total column effective imaginary refractive index (kret) from AERONET inversions at visible and NIR wavelengths17 and Diffuse/Direct irradiance inversions at UV wavelengths11. First, we derive the BC volume fraction (fBC) from AERONET kret at visible and NIR wavelengths from 670 to 1020 nm18. Next, we calculate the BrC volume fraction (fBrC) assuming (1) flat spectral dependence of kBC, (2) known value of kBrC at 368 nm from laboratory absorption measurements or smoke chamber experiments (see Supplementary Fig. S1). Finally, we use the inferred fBC and fBrC to calculate kBrC at short UV-B wavelengths by fitting kret at 305, 311, 317, 325, and 332 nm using MG mixing rule. The details are given below.

BrC volume fraction calculation

Here we demonstrate our strategy of BrC retrievals combining AERONET and UV-MFRSR inversions at UV and visible wavelengths. First, we obtain the BC volume fraction from AERONET retrieved k values at red and NIR wavelengths (670, 870, and 1020 nm) following the method of Schuster et al.18. Second, we apply Arola et al.19 method to calculate the BrC column volume fraction using UV-MFRSR retrievals of k at 368 nm (kret-368) instead of 440 nm. The method assumes a mixture of BC and BrC components embedded in non-absorbing host and applies the Maxwell-Garnett (MG) mixing rule to calculate the effective imaginary refractive index (kcalc), which depends on the volume fractions of BC (fBC) and BrC (fBrC) and their known a priori complex refractive indices (kBC and kBrC). We calculate fBrC by fitting kcalc(fBrC, fBC, kBrC, kBC) to kret-368 assuming lower and upper limits of kBrC-368 (see Fig. S1 in Supplement) and known fixed BC volume fraction (fBC = 0.019) from step 1. Compared to shorter UV-MFRSR UV channels, the 368 nm channel has the advantage of large signal-to-noise (S/N), negligible gaseous absorption, and moderate Rayleigh optical thickness ~0.5 thus reducing uncertainties in UV-MFRSR k inversions.

The retrieval requires a priori knowledge of the BrC complex refractive index. The real part of refractive index, nBrC, is fixed similar to Arola et al.19. We determine the possible range of the imaginary part, kBrC, from prior field and laboratory measurements for absorbing organic aerosols from biomass burning sources (e.g., see Fig. S1 in Supplement). We interpolate prior kBrC measurements to the 368 nm wavelength (kBrC-368) using least squares fitting to the power law spectral dependence (1):

where kBrC is the BrC imaginary refractive index and kBrC-550 is the measured BrC imaginary refractive index at reference wavelength (550 nm)2,6.

This range of kBrC-368 from 0.025 to 0.14 (Supplementary Fig. S1) together with the specific MG mixing rule assumption determines the possible range of calculated fBrC and BrC/BC fraction ratio that are consistent with our retrievals of k: the larger the assumed value of kBrC-368, the smaller the inferred value of fBrC. We obtain the upper limit on fBrC = 0.27 using the smallest reported a priori value of kBrC-368 ~0.025 from Saleh et al.6 and the lower limit value of fBrC = 0.05 using the upper limit of kBrC-368 ~0.14 from Kirchstetter et al.2.

BrC column mass density calculation

In order to derive column mass density for BC and BrC, we multiply their calculated volume fractions, fBC and fBrC by the AERONET-inferred total volume column density integrated over particle size distribution, and the assumed mass density (see equation (6) in Schuster et al.18 for BC and equation (2) in Arola et al.19 for BrC). We assume that the BrC mass density40 is 1.2 gm−3. Thus, lower and upper limits of the BrC column mass density are 10.9 and 61.2 mg/m2, while the average BC column mass density is 6.5 mg/m2 assuming a BC mass density53 equal to 1.8 gm−3.

BrC spectral absorption calculation in UV

We derive kBrC at UV wavelengths of 332, 325, 317, 311, and 305 nm by fitting UV-MFRSR retrieved kret assuming a fixed value of fBrC = 0.05 (0.27) inferred from kret-368 and known fBC = 0.019 calculated from step 1 (Fig. 3). In other words, we modified the algorithm to infer kBrC by fitting retrieved kret and kcalc at short UV wavelengths using fixed values of fBC and fBrC calculated in previous steps 1 and 2. Finally, we fit derived kBrC at several UV-B and UV-A wavelengths to the power law equation (2) similarly to equation (1).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Mok, J. et al. Impacts of brown carbon from biomass burning on surface UV and ozone photochemistry in the Amazon Basin. Sci. Rep. 6, 36940; doi: 10.1038/srep36940 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Myhre, G. et al. Radiative forcing of the direct aerosol effect from AeroCom Phase II simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 1853–1877 (2013).

Kirchstetter, T. W., Novakov, T. & Hobbs, P. V. Evidence that the spectral dependence of light absorption by aerosols is affected by organic carbon. J. Geophys. Res. 109, D21208 (2004).

Chen, Y. & Bond, T. C. Light absorption by organic carbon from wood combustion. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 1773–1787 (2010).

Lack, D. A. et al. Brown carbon and internal mixing in biomass burning particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 14802–14807 (2012).

Saleh, R. et al. Absorptivity of brown carbon in fresh and photo-chemically aged biomass-burning emissions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 7683–7693 (2013).

Saleh, R. et al. Brownness of organics in aerosols from biomass burning linked to their black carbon content. Nature Geosci. 7, 647–650 (2014).

Feng, Y., Ramanathan, V. & Kotamarthi, V. R. Brown carbon: a significant atmospheric absorber of solar radiation? Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 8607–8621 (2013).

Dickerson, R. R. et al. The impact of aerosols on solar ultraviolet radiation and photochemical smog. Science 278, 827–830 (1997).

He, S. & Carmichael, G. R. Sensitivity of photolysis rates and ozone production in the troposphere to aerosol properties. J. Geophys. Res. 104, 26307–26324 (1999).

Krotkov, N. A., Bhartia, P. K., Herman, J. R., Fioletov, V. & Kerr, J. Satellite estimation of spectral surface UV irradiance in the presence of tropospheric aerosols: 1. Cloud-free case. J. Geophys. Res. 103, 8779–8793 (1998).

Krotkov, N. A. et al. Aerosol ultraviolet absorption experiment (2002 to 2004), part 2: absorption optical thickness, refractive index, and single scattering albedo. Opt. Eng. 44, 041005 (2005).

Arola, A. et al. A new approach to correct for absorbing aerosols in OMI UV. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L22805 (2009).

Teramura, A. H. & Sullivan, J. H. Effects of UV-B radiation on photosynthesis and growth of terrestrial plants. Photosynth. Res. 39, 463–473 (1994).

Rousseaux, M. C. et al. Ozone depletion and UVB radiation: Impact on plant DNA damage in southern South America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 15310–15315 (1999).

Lautenschlager, S., Wulf, H. C. & Pittelkow, M. R. Photoprotection. Lancet 370, 528–537 (2007).

Holben, B. N. et al. AERONET—A Federated Instrument Network and Data Archive for Aerosol Characterization. Remote Sens. Environ. 66, 1–16 (1998).

Dubovik, O. et al. Variability of absorption and optical properties of key aerosol types observed in worldwide locations. J. Atmos. Sci. 59, 590–608 (2002).

Schuster, G. L., Dubovik, O., Holben, B. N. & Clothiaux, E. E. Inferring black carbon content and specific absorption from Aerosol Robotic Network (AERONET) aerosol retrievals. J. Geophys. Res. 110, D10S17 (2005).

Arola, A. et al. Inferring absorbing organic carbon content from AERONET data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 215–225 (2011).

Lu, Z. et al. Light Absorption Properties and Radiative Effects of Primary Organic Aerosol Emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol., 49, 4868–4877 (2015).

Krotkov, N. A. et al. Aerosol ultraviolet absorption experiment (2002 to 2004), part 1: ultraviolet multifilter rotating shadowband radiometer calibration and intercomparison with CIMEL sunphotometers. Opt. Eng. 44, 041004 (2005).

Krotkov, N. A. et al. Aerosol column absorption measurements using co-located UV-MFRSR and AERONET CIMEL instruments. Proc. SPIE 7462, Ultraviolet and Visible Ground- and Space-based Measurements, Trace Gases, Aerosols and Effects VI, 746205 (2009).

Buchard, V., Brogniez, C., Auriol, F. & Bonnel, B. Aerosol single scattering albedo retrieved from ground-based measurements in the UV and visible region. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 4, 1–7 (2011).

Eck, T. F. et al. Wavelength dependence of the optical depth of biomass burning, urban, and desert dust aerosols. J. Geophys. Res. 104, 31333–31349 (1999).

Torres, O. et al. OMI and MODIS observations of the anomalous 2008–2009 Southern Hemisphere biomass burning seasons. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 3505–3513 (2010).

Torres, O. et al. Aerosols and surface UV products from Ozone Monitoring Instrument observations: An overview. J. Geophys. Res. 112, D24S47 (2007).

Jethva, H., Torres, O. & Ahn, C. Global assessment of OMI aerosol single-scattering albedo using ground-based AERONET inversion. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 119, 9020–9040 (2014).

Laskin, A., Laskin, J. & Nizkorodov, S. A. Chemistry of Atmospheric Brown Carbon. Chem. Rev. 115, 4335−4382 (2015).

Dickerson, R. R., Measurements of reactive nitrogen compounds in the free troposphere. Atmos. Environ. 18, 2585−2593 (1984).

Pickering, K. E. et al. Photochemical ozone production in tropical squall line convection during NASA Global Tropospheric Experiment/Amazon Boundary Layer Experiment 2 A. J. Geophy. Res. 96, 3099–3114 (1991).

Schuster, G. L., Dubovik, O. & Arola, A. Remote sensing of soot carbon–Part 1: Distinguishing different absorbing aerosol species. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 1565–1585 (2016).

Moosmuller, H., Chakrabaty, R. K., Ehlers, K. M. & Arnott, W. P. Absorption Angstrom Coefficient, Brown Carbon, and Aerosols: Basic Concepts, Bulk Matter, and Spherical Particles. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 1217–1225 (2011).

Wang, X. et al. Exploiting simultaneous observational constraints on mass and absorption to estimate the global direct radiative forcing of black carbon and brown carbon. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 10989–11010 (2014).

Jethva, H. & Torres, O. Satellite-based evidence of wavelength-dependent aerosol absorption in biomass burning smoke inferred from Ozone Monitoring Instrument. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 10541–10551 (2011).

Lack, D. A. & Langridge, J. M. On the attribution of black and brown carbon light absorption using the Ångström exponent. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 10535–10543 (2013).

Srinivas, B., Rastogi, N., Sarin, M. M., Singh, A. & Singh, D. Mass absorption efficiency of light absorbing organic aerosols from source region of paddy-residue burning emissions in the Indo-Gangetic Plain. Atmos. Environ. 125, 360–370 (2016).

Yan, C. et al. Chemical characteristics and light-absorbing property of water-soluble organic carbon in Beijing: Biomass burning contributions. Atmos. Environ. 121, 4–12 (2015).

Hoffer, A. et al. Optical properties of humic-like substances (HULIS) in biomass-burning aerosols. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 6, 3563–3570 (2006).

Schuster, G. L., Lin, B. & Dubovik, O. Remote sensing of aerosol water uptake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L03814 (2009).

Turpin, B. J. & Lim, H. J. Species contributions to PM2.5 mass concentrations: Revisiting common assumptions for estimating organic mass. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 35, 602–610 (2001).

Reid, J. S., Koppmann, R., Eck, T. F. & Eleuterio, D. P. A review of biomass burning emissions part II: intensive physical properties of biomass burning particles. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 5, 799–825 (2005).

Reid, J. S. et al. Real-time monitoring of South American smoke particle emissions and transport using a coupled remote sensing/box-model approach. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L06107 (2004).

Barnard, J. C., Volkamer, R. & Kassianov, E. I. Estimation of the mass absorption cross section of the organic carbon component of aerosols in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 8, 6665–6679 (2008).

Chakrabarty, R. K. et al. Brown carbon aerosols from burning of boreal peatlands: microphysical properties, emission factors, and implications for direct radiative forcing. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 3033–3040 (2016).

Srinivas, B. & Sarin, M. M. Brown carbon in atmospheric outflow from the Indo-Gangetic Plain: Mass absorption efficiency and temporal variability. Atmos. Environ. 89, 835–843 (2014).

Mancebo, S. E. & Wang, S. Q. Skin cancer: role of ultraviolet radiation in carcinogenesis. Rev. Environ. Health 29, 265–273 (2014).

Arola, A. et al. Assessment of TOMS UV bias due to absorbing aerosols. J. Geophys. Res. 110, D23211 (2005).

Hodzic, A. et al. Wildfire particulate matter in Europe during summer 2003: meso-scale modeling of smoke emissions, transport and radiative effects. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 7, 4043–4064 (2007).

Castro, T., Madronich, S., Rivale, S., Muhlia, A. & Mar, B. The influence of aerosols on photochemical smog in Mexico City. Atmos. Environ. 35, 1765–1772 (2001).

Albuquerque, L. M. M. et al. Sensitivity studies on the photolysis rates calculation in Amazonian atmospheric chemistry–Part I: The impact of the direct radiative effect of biomass burning aerosol particles. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 5, 9325–9353 (2005).

Hammer, M. S. et al. Interpreting the ultraviolet aerosol index observed with the OMI satellite instrument to understand absorption by organic aerosols: implications for atmospheric oxidation and direct radiative effects. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 2507–2533 (2016).

Johnston, F. H. et al. Estimated Global Mortality Attributable to Smoke from Landscape Fires. Environ. Health Perspect. 120, 695–701 (2012).

Bond, T. C. & Bergstrom, R. W. Light Absorption by Carbonaceous Particles: An Investigative Review. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 40, 27–67 (2006).

Allen, J. In “Fires and Smoke Across South America” published in NASA Earth Observatory website on 07/11/2007 (Available online at: http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=8033&eocn=image&eoci=related_image Retrieved 07/12/2016).

Acknowledgements

J.M. and Z.L. were supported by ESSIC–NASA Master grant (5266960), the National Science Foundation (AGS1118325, AGS1534670), MOST (2013CB955804), and NSFC (91544217). G.S. and S.O. were supported by the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) and used the resources of the Supercomputing Laboratory at KAUST in Thuwal, Saudi Arabia. The authors acknowledge support from NASA Earth Science Division, Radiation Sciences and Atmospheric Composition programs. The authors also thank the AERONET and UV-B Monitoring and Research Program team members.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M. performed data analysis and wrote the manuscript. N.A.K. developed UV-MFRSR retrieval algorithm and validated with AERONET retrievals. Z.L. initiated the project. O.T. and H.J. performed satellite OMI aerosol absorption retrievals. H.J. also helped in developing the software for cosine correction and calibration of the UV-MFRSR instrument. R.R.D. and X.R. performed chemical box model runs and interpretations. T.F.E. quality assured AERONET data and participated in interpretations of results. A.A. developed first retrievals of brown carbon volume fraction using AERONET inversions. G.S. and S.O. calculated aerosol effects on photolysis rates necessary for a chemical box model. G.L., O.T., and M.A. performed the field measurements. All authors discussed the data and commented on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Mok, J., Krotkov, N., Arola, A. et al. Impacts of brown carbon from biomass burning on surface UV and ozone photochemistry in the Amazon Basin. Sci Rep 6, 36940 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36940

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36940

This article is cited by

-

More water-soluble brown carbon after the residential “coal-to-gas” conversion measure in urban Beijing

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2023)

-

Quantitative evaluation of mixed biomass burning and anthropogenic aerosols over the Indochina Peninsula using MERRA-2 reanalysis products validated by sky radiometer and MAX-DOAS observations

Progress in Earth and Planetary Science (2022)

-

Characterization of carbonaceous aerosols during the Indian summer monsoon over a rain-shadow region

Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.