Abstract

Tibetan loaches are the largest group of Tibetan fishes and are well adapted to the Tibetan Plateau. To investigate the origin of Tibetan loaches and their adaptations to the Tibetan Plateau, we determined 32 complete mitochondrial genomes that included 29 Tibetan loach species, two Barbatula species and Schistura longus. By combining these newly determined sequences with other previously published mitochondrial genomes, we assembled a large mitogenomic data set (11,433 bp) of 96 species in the superfamily Cobitoidea, to investigate the phylogenetic status of the genus Triplophysa. The resulting phylogeny strongly supported that the genus Triplophysa forms a monophyletic group within Nemacheilidae. Our molecular dating time suggests that the lineage leading to the Tibetan loaches and other loaches diverged approximately 23.5 Ma, which falls within the period of recent major uplifts of the Tibetan Plateau in the Early Miocene. Selection analyses revealed that the mitochondrial protein-coding genes of Tibetan loaches have larger ratios of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitutions than do those of non-Tibetan loaches, indicating that Tibetan loaches accumulated more nonsynonymous mutations than non-Tibetan loaches and exhibited rapid evolution. Two positively selected sites were identified in the ATP8 and ND1 genes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mitochondria are the energy metabolism centers of the cell and play critical roles in ATP synthesis and heat generation via cellular respiration. More than 95% of cellular energy is generated by mitochondria through oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Mitochondrial-encoded OXPHOS genes may therefore evolve under selection due to metabolic requirements and display evidence of adaptive evolution in mammals, birds and fishes1,2,3. Taxa subject to the cold and hypoxic conditions of high-altitude habitats have undergone alterations in mitochondrial function through changes in mitochondrial DNA4. Numerous studies have demonstrated the role of selection in mtDNA evolution and detected signals of positive selection in mitochondrial genes in endemic taxa of the Tibetan Plateau, including Tibetan humans5, the plateau pika6, the Tibetan horse7,8, the Tibetan antelope9, the Tibetan wild yak10, the Tibetan sheep11, Chinese snub-nosed monkeys12, galliform birds13 and schizothoracine fishes14. Mitochondria function in supplying cellular energy and are therefore extremely sensitive to energy-related selective pressure; furthermore, their small genome size, high substitution rate and easily accessible nature15 make them useful markers for phylogenetic reconstructions. Therefore, the mitogenome (mitochondrial genome) is widely used to not only explore phylogenetic relationships and estimate divergence times at different taxonomic levels16,17,18 but also detect signals of positive selection2,3,10.

The Superfamily Cobitoidea is comprised of seven monophyletic families Gyrinocheilidae, Catostomidae, Cobitidae, Botiidae, Vaillantellidae, Balitoridae and Nemacheilidae19. The Nemacheilidae is the largest group in the superfamily Cobitoidea, including numerous morphologically similar nemacheilid loaches20. Among the nemacheilid loaches, Triplophysa fishes have long been of great interest to researchers. The genus Triplophysa constitutes the largest of three major groups of Tibetan fishes and consists of 140 species reported in FishBase21, belonging to the family Nemacheilidae within the order Cypriniformes. Triplophysa species are widely distributed in the Tibetan Plateau and adjacent regions22. Studies of the morphological characteristics and geographical distribution of Triplophysa have suggested that the origin and evolution of this group is related to the uplift of the Tibetan Plateau22,23. The cold and hypoxic conditions of high-altitude habitats impose severe physiological challenges to organisms living in the Tibetan Plateau. As representative endemic species of the Tibetan Plateau, Triplophysa species are well adapted to the high-altitude environment. Nevertheless, except for some suggestions of mtDNA variation in Triplophysa associated with adaptation to high-altitude habitats6,24, an understanding of the genetic mechanisms that underlie the adaptations of this group to their high-altitude environment from a mitogenomic perspective is lacking. Moreover, the phylogenetic placement of Triplophysa and its divergence time from other nemacheilid loaches are not well understood.

In this study, we analyzed 32 complete, newly determined mitogenomes along with 64 published mitogenomes of the superfamily Cobitoidea, to 1) confirm the phylogenetic status of the genus Triplophysa within Nemacheilidae based on mitochondrial genomes and broad taxon sampling, 2) date the origin of the Triplophysa lineages, and 3) provide a comprehensive view of the adaptive evolution of the mitogenome in Triplophysa species during their independent acclimatization to high-altitude environments.

Results

Characteristics of the mitochondrial genome

The mitogenome sizes of the sequenced Triplophysa fishes ranged from 16,562 bp to 16,681 bp, and all of the mitogenomes exhibited similar sequence characteristics. Differences in mitogenome size resulted from variation in the length of the control regions. The gene arrangement, organization and content of the mitochondrial genome of Triplophysa fishes are similar to those of other teleosts25,26, which also contain 13 protein-coding genes, two ribosomal RNA genes (rRNA), 22 transfer RNA genes (tRNA), and a putative control region (CR). In the present study, the mitochondrial PCGs, tRNAs, rRNAs and CR were encoded on the heavy strand except for ND6 and eight tRNA genes (tRNA-Gln, tRNA-Ala, tRNA-Asn, tRNA-Cys, tRNA-Tyr, tRNA-Ser, tRNA-Glu, and tRNA-Pro), which were encoded on the light strand. The concatenated data set consisted of 11,433 bp from 13 PCGs of 96 mitochondrial genomes. Of the identified sites, 6,081 (53.2%) sites were variable and 5,387 sites (47.1%) were parsimony informative. Additional details on the concatenated gene sequences and each of the 13 mitochondrial protein-coding genes (alignment length, variable sites, parsimony-informative sites, mean nucleotide composition, and transition/transversion ratios) are provided in Table 1. The examined mitochondrial genomes exhibited AT-bias (ranging from 52.4 to 58.5; average = 56.0).

Phylogenetic status of the genus Triplophysa

Both the saturation plots and the Iss index values derived using DAMBE revealed no clear saturation for any codon position in the concatenated alignment (Figure S1). The combined data set of the 13 PCGs (total = 11,433 bp), including all codon positions, was used to conduct the phylogenetic analysis.

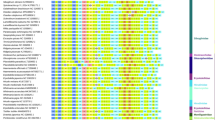

The ML and BI phylogenetic analyses of the concatenated data sets yielded consistent topological relationships for loaches with high bootstrap support values and Bayesian posterior probabilities (Fig. 1). Herein, ML bootstrap support values >70 and BI posterior probabilities >0.95 were defined as strongly supportive. The nodal support values obtained from two building methods are shown together on the BI topology (Fig. 1). The ML and BI trees strongly supported the monophyly of the loach clade. Within Cobitoidea, Gyrinocheilidae and Catostomidae rooted the phylogenetic tree. The remaining members of Cobitoidea represented a monophyletic group with strong nodal support and were resolved as ((Botiidae, Vaillantellidae), ((Cobitidae, Balitoridae), Nemacheilidae)). Vaillantellidae formed the sister group to the Botiidae clade with robust statistical support (posterior probability [PP] = 1.00 and bootstrap proportion [BP] = 81). Vaillantellidae and Botiidae formed the basal sister group to the other loaches and Cobitidae and Balitoridae formed a sister clade to Nemacheilidae. The above groups were used as outgroups while the family Nemacheilidae was used as the ingroups. Therefore, the family Nemacheilidae, especially the Triplophysa group is deserved our concern. A reasonably well-resolved phylogeny was yielded: the diverse nemacheilid loaches formed a monophyletic group with strong nodal support ([PP] = 1.00 and [BP] = 100), which comprised of 6 genera: Acanthocobitis, Schistura, Lefua, Homatula, Barbatula and Triplophysa. Each genera sampled formed its own monophyletic group, and most of the within-genera species relationships yielded high support values. The largest group, Triplophysa, was strongly supported as monophyletic ([PP] = 1.00 and [BP] = 100) with the exception of Hedinichthys yarkandensis, which is listed as a species of the subgenus Hedinichthys.

At each node, the upper and lower rectangles with deferent colcor indicate the Bayesian posterior probability and the bootstrap value for the ML analyses, respectively. Branch lengths were estimated by using Bayesian inference method. (Scale bar represents 0.08 substitutions per site). Note: * represents the mitochondrial genome sequence has been sequenced in the previous study.

Divergence time estimation for the Triplophysa lineage

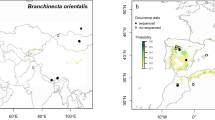

We provided a timescale for loaches through MCMCTREE analysis. The estimated divergence times for loaches are shown in Fig. 2 with 95% credible intervals (CIs). The most recent common ancestor of loaches date to 33.8 Ma (95%CI: 30.7–38.2 Ma). The family Vaillantellidae diverged from the family Botiidae at 30 Ma (95%CI: 23.8–35.4 Ma), whereas the Balitoridae diverged from the Cobitidae at 29 Ma (95%CI: 26.3–30.8 Ma). The most recent common ancestor of Nemacheilidae date to 28 Ma (95%CI: 26.1–30.2 Ma). The adaptive radiation of Triplophysa fishes is a major event in the evolution of nemacheilid loaches, with Triplophysa being the largest group within the Nemacheilidae. This group diverged from the other loaches within the Nemacheilidae at 23.5 Ma (95%CI: 20.5–26.1 Ma), and the most recent common ancestor of Triplophysa group arose 21.3 Ma (95%CI: 18.2–24.1 Ma).

Selection analysis

Selection analysis yielded a separate dN/dS ratio for each terminal branch of the phylogenetic tree (Table S1). The dN/dS ratio of Tibetan loaches was significantly larger than that of non-Tibetan loaches for the 13 concatenated mitochondrial protein-coding genes (Wilcoxon rank sum test, P = 0.03016). Moreover, each of the 13 mitochondrial protein-coding genes had a larger dN/dS ratio in the Tibetan loaches than in the non-Tibetan loaches (Fig. 3). In particular, the dN/dS ratios of COX1, ND4, ND4L, and ND6 in the Tibetan loaches were significantly larger than those in the non-Tibetan loaches (Wilcoxon rank sum test, P = 0.004286, 0.00044, 0.007778, and 0.02895, respectively) among all of the mitochondrial protein-coding genes. These results implied that Tibetan loaches experienced weaker purifying selection at mitochondrial protein-coding genes than did non-Tibetan loaches and that the former accumulated more nonsynonymous mutations.

(A) Comparisons of average dN/dS ratios for 13 individual protein-coding genes between Triplophysa fishes and Non-Triplophysa fishes. Note: *0.01 < P < 0.05, **0.001 < P < 0.01. (B) dN and dS estimated for the positive gene ATP8 using the FEL analysis method. The red arrow indicates the position of positive selected site. (C) dN and dS estimated for the positive gene ND1 using the FEL analysis method. The red arrow indicates the position of positive selected site.

The FEL analysis identified two positively selected sites in the ATP8 (corresponding to site 38, dN/dS = 3.228154003, P = 0.027923387) and ND1 (corresponding to site 80, dN/dS = 6.933321774, P = 0.049226799) genes (Fig. 3, Table S2).

Discussion

The loaches are generally recognized as comprising five families, i.e., Botiidae, Vaillantellidae, Cobitidae, Balitoridae, and Nemacheilidae, according to morphological characters27,28 and molecular data19,29. As a diverse group, the phylogenetic relationships of loaches have been studied extensively in the order Cypriniformes18,19,30,31. Nevertheless, previous studies did not recover a comprehensively consistent phylogenetic tree. Slechtova et al.19 confirmed the family status of the Vaillantellidae, but some discrepancies remained regarding its placement: Vaillantellidae, Botiidae or both were found to occupy the basal position among the loaches18,19,25,31. The present analysis strongly supports the clustering of Vaillantellidae and Botiidae as a basal clade within the loach families. The remaining loaches (Cobitidae, Balitoridae, and Nemacheilidae) have been clustered into a single clade18,30, which is supported by our analysis. However, conflicting results have been obtained regarding the sister-group relationships among these three families. A sister relationship between Balitoridae and Nemacheilidae is supported by some previous studies18,19,30, whereas a sister relationship between Cobitidae and Nemacheilidae was proposed by Tang et al.20. However, all of these studies involved a limited number of taxa or genes. For example, only one species of Balitoridae, Homaloptera leonardi, was included in the study by Mayden et al. 2009, and a single RAG1 gene was used for the phylogenetic reconstruction of Cobitoidea by Slechtova et al.19. Therefore, compared with the taxon data of previous studies, our study incorporated the largest data set of loach mitochondrial genomes. In the present study, the sister relationship between Cobitidae and Balitoridae is resolved, and Nemacheilidae forms a monophyletic group. Our analysis clustered Hedinichthys with Schistura within Nemacheilidae instead of with Triplophysa, which indicates that Hedinichthys yarkandensis is not a genuine Tibetan loach. He et al.32, found that Hedinichthys clustered with the genus Lefua based on analysis of the CYTB gene. We suggest that the placement of Hedinichthys should be redefined. The genus Triplophysa should exclude the subgenus Hedinichthys, recovering the genus Triplophysa as a monophyletic group.

A previous study found a correlation between the geological and biotic evolution of the Tibetan Plateau in a paleobiogeographical analysis of freshwater fishes33. Therefore, it is important for researchers to consider the divergence time of Triplophysa within the context of the geological history of the Tibetan Plateau. Previously, He et al.32 concluded that Triplophysa diverged from the other loaches of the family Nemacheilidae 13.5–10.3 Ma ago based on strict molecular clock estimation. Wang et al.24, proposed that Triplophysa rosa diverged from other Triplophysa species approximately 48.3 Ma (34.7–59.5 Ma) ago based on analysis of combined CYTB and D-loop sequences. Our age estimation for Triplophysa is incongruent with the above molecular clock estimations. Our molecular dating results indicate that the most recent common ancestor of Triplophysa fishes diverged from other nemacheilid loaches approximately 23.5 Ma (95% CI: 20.5–26.1 Ma). With respect to the origin of schizothoracine fishes, Ruber et al.34 revealed the common ancestor of the schizothoracine fishes was in the Oligocene-Miocene boundary (around 23 Ma) or older based on the relaxed molecular clock analysis of cyprinids from cytochrome b. Therefore, the molecular dating time of the Tibetan loach lineage is consistent with that of the schizothoracine fishes. Tibetan loaches are mainly distributed in the high-altitude lakes of the Himalayas. Considering this distribution and our divergence time estimates, we hypothesize that the formation of this distribution pattern is likely associated with the concomitant ecological changes that occurred during the Tibetan Plateau uplift process. It is reported that southern Tibet and the Himalayas began to uplift due to rapid crustal thickening in the Early Miocene approximately 21–17 Ma ago35,36,37. Our estimate of the origin of Triplophysa is compatible with the timing of the geological events that occurred during the rapid uplift in Tibet. Therefore, we assume that the uplift of the Tibetan Plateau played an important role in the speciation of Triplophysa fishes in the Early Miocene. At the same time, the divergence date estimates of Triplophysa fishes might reflect the occurrence of geological events associated with the uplift of plateau. The rapid and persistent rise of the Tibetan Plateau began approximately 8 Ma38; its ultimate height did not lead to the extinction of Triplophysa but rather its adaptation to the extreme environment.

Previously, Sun et al.3 proposed that mitochondrial genes have undergone adaptive evolution in teleosts because of their different metabolic requirements. They divided the mitochondrial data set of 401 fishes into “migratory” and “nonmigratory” groups and tested functional constraints act on mitochondria. In comparision, the size of data sets (96 complete mitochondrial genomes) in this study is smaller than that of the previous study. Nevertheless, our results also detected the significant difference between the dN/dS ratios of Tibetan loaches and the non-Tibetan loaches. Compared with the non-Tibetan loaches (ω = 0.04834), the Tibetan loaches (ω = 0.10665) had a significantly larger mean ω (dN/dS) ratio for the 13 concatenated mitochondrial protein-coding genes, indicating that the high-altitude groups have accumulated more nonsynonymous mutations. These nonsynonymous mutations have resulted in slightly beneficial amino acid changes that allowed adaption to the high-altitude environments. Individually, the 13 mitochondrial protein-coding genes were also shown to have larger dN/dS ratios in the Tibetan loaches than in the non-Tibetan loaches, which provide consistent evidence for accelerated evolution at the mitogenome level in Tibetan loaches compared with non-Tibetan loaches. A previous study of galliform birds also found a larger mean ω (dN/dS) ratio for 13 concatenated mitochondrial protein-coding genes in the branches of high-altitude birds13. Previously, we found evidence of genome-wide, rapid evolution of Tibetan loaches relative to fishes living at low altitudes from our analysis of Tibetan loach transcriptome data39. Tibetan loaches adapted well to the severe conditions of the Tibetan Plateau by means of accelerated evolutionary rates. Martin and Palumbi40 proposed that the larger dN/dS in mitochondrial genes could be related to some physiological variables, such as metabolic rate. Considering the distribution of Triplophysa and our divergence time estimate, these results suggest that the evolutionary rate of Triplophysa fishes might be influenced by the geological events of the Tibetan Plateau uplift in the Early Miocene.

Among the 13 mitochondrial protein-coding genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), ND1 and ATP8 have undergone positive selection. ND1 is one of seven subunits in NADH dehydrogenase; it is the first and largest enzyme complex and acts as a proton pump41,42. ATP8 is one of two subunits in ATP synthase; it is the last enzyme complex and uses a concentration gradient of protons to produce ATP43,44. Numerous studies have indicated that the adaptive evolution of the NADH dehydrogenase complex and ATP synthase has been vital in the evolution of energy generation by oxidative phosphorylation8,13,14,41,45. We suggest that both the ND1 and ATP8 genes are responsible for high-altitude adaptation in Triplophysa fishes. Similarly, with respect to the high altitude adaptation in schizothoracine fishes, Li et al.14 found the positively selected sites in ND1 gene. On the contrary, they also detected the positively selected sites in ATP6, CYTB, ND2, ND4 and ND5 genes. These results suggested that Tibetan loaches and schizothoracine fishes probably employ different genic toolkit to adapt to the extreme environment of the Tibetan Plateau.

Materials and Methods

All the methods were carried out in accordance with approved guidelines. All experimental protocols involving animals in this study were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Specimen collection and DNA extraction

Specimen information for 29 Triplophysa species, two Barbatula species, and Schistura longus is provided in Table 2. The species identification was following the previous book22. All of the samples were stored in 95% ethanol until DNA extraction. Total genomic DNA was extracted from muscle or fin tissue using a standard phenol/chloroform extraction method46.

Mitochondrial genome sequencing, assembly and annotation

The 17 PCR amplification primer sets used for the mitogenomes are described in Table S3. The primers were designed from the conserved regions identified based on the alignment of 15 complete mitogenomes available for Nemacheilidae (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). PCR was carried out in 30 μl reaction volumes containing 19.7 μl sterilized distilled water, 4 μl of 10 × PCR buffer II (Takara, China), 2.0 μl dNTP (2.5 mM), 1.5 μl of each primer (10 μM), 0.3 μl of Taq (5U/μl Takara, China), and 1.0 μl of template DNA (appropriate 30 ng). The cycling protocol was as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 4 min followed by 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 50–55 °C for 40 s, and 72 °C for 2 min, with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1.0% agarose gel, purified with a DNA Agarose Gel Extraction Kit (Omega, USA) and sequenced using an ABI3730xl sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

The sequences were edited and assembled using the SeqMan program from the Lasergene package (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI, USA). The protein-coding genes, rRNA genes, tRNA genes and non-coding regions of mitogenomes were annotated using MitoAnnotator47. Newly determined mitogenome sequences were deposited in GenBank (Table S4).

Phylogenetic reconstruction

Including the 32 complete mitogenomes that were newly determined in this study, a total of 96 mitochondrial genomes were used in the phylogenetic analysis, including the outgroup Catostomidae and Gyrinocheilidae. The taxonomic information, accession numbers and mitogenome sizes are provided in Table S4. The nucleotide sequences of the 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs) were first extracted using purpose-built perl scripts48 based on annotations and then separately aligned according to their corresponding amino acid translations using the software TranslatorX49. The gaps were not removed as they are known to contain valuable information for phylogenetic analyses50. The concatenated nucleotide sequence alignment from 13 PCGs (total = 11,433 bp) without stop codons was generated with our in-house scripts to conduct the phylogenetic analysis. Tests of the base substitution saturation were performed prior to the phylogenetic reconstruction. The extent of substitution saturation was estimated separately for entire codons and for the first, second, and third codon positions of the concatenated alignment using DAMBE51. The pairwise nucleotide differences (transitions and transversions) were plotted against the GTR genetic distance.

The best-fit global model GTR+I+G was selected for the alignment of the 13 concatenated PCGs based on the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) using jModelTest2.1.352. To improve the reliability of the phylogenetic analysis, the best-fit partitioning scheme across each gene and codon position was determined for each data set under the Bayesian information criterion using PartitionFinder software53.

Both partitioned maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian Inference (BI) approaches with the selected partition scheme (Table S5) were employed to reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships among the loach families. We implemented the Bayesian phylogenies in MrBayes v3.2.354,55 with the “unlink” and “prest ratepr = variable” model parameters. Two independent runs were performed with four independent Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains (three hot and one cold) for 50,000,000 generations initiated from a random tree, sampling one tree every 1000 generations. Convergence of the BI analyses was first assessed by the average standard deviation of split frequencies less than 0.01 and the potential scale reduction factors (PSRF) close to 1.0 for all parameters. We also used Tracer v1.6 software56 to investigate the convergence of the BI analyses. The first 12,500 trees were discarded as conservative burn-in, and the remaining samples were used to generate a majority-rule consensus tree. The support values of the BI tree were estimated by Bayesian posterior probability (BPP). The ML phylogenetic analysis was implemented in RAxML v8.1.1757 with the GTRGAMMAI model. 1,000 rapid bootstrapping replications were used to evaluate the bootstrap support values of the ML phylogenetic tree and search for the best-scoring ML tree.

Divergence time estimation

MCMCTREE in PAML v4.8 was implemented to estimate divergence times with an approximate likelihood calculation58. The ML phylogenetic tree topology from the 13 concatenated PCGs was used for divergence time estimation, and the ML branch lengths were estimated using the BASEML program in PAML under the GTR substitution model with the gamma prior set at 0.5. Two priors, the overall substitution rate (rgene gamma) and rate-drift parameter (sigma2 gamma), were set at G (1, 4.5) and G (1, 1.52), respectively, using the strict molecular-clock assumption with a root age of 152 Ma, which is suggested by previous studies59 (http://www.timetree.org/search/pairwise/). The independent rates model (clock = 2 in MCMCTREE)60 was used to specify the prior of rates among the internal nodes, which followed a log-normal distribution. The three parameters (birth rate λ, death rate μ and sampling fraction ρ) in the birth-death process with species sampling were specified as 1, 1, and 0, respectively. A loose maximum bound for the root was set at >0.658 <1.800 (i.e., between 65.8 Ma and 180 Ma).

The following four fossil calibrations were incorporated in this study: 1) The minimum age of Catostomidae is 60 Ma based on a catostomid fossil from the Paleocene61. 2) The oldest fossil of Plesiomyxocyprinus arratiae similar to Myxocyprinus asiaticus was constrained to from the middle Eocene or earlier, approximately 38–40 Ma62. 3) The estimated divergence time between Cobitinae and Nemacheilinae is approximately 30 Ma63. 4) The fossil calibrations of the genus Cobitis were recorded as 13.8–15.9 Ma64 (http://www.wahre-staerke.com/). The first 200,000 cycles in MCMCTREE were discarded as burn-in, and every 50 cycles were sampled to obtain a total of 20,000 samples. To ensure that convergence was reached, two replicate MCMC runs were initiated with two different random seeds. The distributions of the parameter values from the MCMC samples were assessed using Tracer v1.6 (ESS > 200)56.

Analysis of selective pressure

The codeml program in the PAML package58 with the free ratio model (model = 1) was used to estimate the ratio of nonsynonymous (dN) to synonymous (dS) substitutions rates (ω = dN/dS), which allowed for a separate dN/dS ratio for each branch on a tree. From the optimized ML tree topology derived from the 13 concatenated protein-coding genes, the dN/dS ratios of the 13 concatenated mitochondrial protein-coding genes and the 13 individual genes were computed separately for the terminal branches to evaluate the selective pressure operating on the mtDNA genomes. The dN/dS ratios for each terminal branch were divided into two groups: Tibetan loaches and non-Tibetan loaches. We tested the statistical significance of the differences in the dN/dS ratios of each gene between the Tibetan and non-Tibetan loaches using the Wilcoxon rank sum test implemented in R v2.10.065.

To identify the genes that have undergone positive selection for high-altitude adaptation, a branch model and a branch site model were employed to detect significant changes in selective pressure. However, the results of likelihood ratio tests (LRTs) for each mitochondrial gene were not significant. Therefore, the fixed-effects likelihood (FEL) approach implemented in HyPhy software66 was used to detect site-specific selection pressure; this approach is more powerful than the codeml program for detecting individual sites subject to episodic diversifying selection67. The FEL approach was run using the best-fitting nucleotide substitution model for each gene that was identified by jModelTest2.1.352 on the ML phylogenetic tree. The subtree consisting of the 35 Tibetan loaches was specified as the foreground branch and tested while the rest of the branches shared an arbitrary dN/dS ratio. Two models were nested in this method: H0, dN = dS (the neutral model) and HA, where dN and dS are estimated independently (the selection model). A nominal significance level of 0.1 for the likelihood ratio test was chosen based on the desired power of this analysis. When the LRT is significant, if dN > dS, the site is declared to be under positive selection, otherwise the site is under negative selection.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Wang, Y. et al. Mitogenomic perspectives on the origin of Tibetan loaches and their adaptation to high altitude. Sci. Rep. 6, 29690; doi: 10.1038/srep29690 (2016).

References

Shen, Y. Y. et al. Adaptive evolution of energy metabolism genes and the origin of flight in bats. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107, 8666–8671 (2010).

Shen, Y. Y., Shi, P., Sun, Y. B. & Zhang, Y. P. Relaxation of selective constraints on avian mitochondrial DNA following the degeneration of flight ability. Genome research 19, 1760–1765 (2009).

Sun, Y. B., Shen, Y. Y., Irwin, D. M. & Zhang, Y. P. Evaluating the roles of energetic functional constraints on teleost mitochondrial-encoded protein evolution. Mol Biol Evol 28, 39–44 (2011).

Luo, Y., Yang, X. & Gao, Y. Mitochondrial DNA response to high altitude: a new perspective on high-altitude adaptation. Mitochondrial DNA 24, 313–319 (2013).

Gu, M. L. et al. Differences in mtDNA whole sequence between Tibetan and Han populations suggesting adaptive selection to high altitude. Gene 496, 37–44 (2012).

Luo, Y. et al. Mitochondrial genome analysis of Ochotona curzoniae and implication of cytochrome c oxidase in hypoxic adaptation. Mitochondrion 8, 352–357 (2008).

Ning, T., Xiao, H., Li, J., Hua, S. & Zhang, Y. P. Adaptive evolution of the mitochondrial ND6 gene in the domestic horse. Genet Mol Res 9, 144–150 (2010).

Xu, S. et al. High altitude adaptation and phylogenetic analysis of Tibetan horse based on the mitochondrial genome. Journal of genetics and genomics = Yi chuan xue bao 34, 720–729 (2007).

Xu, S. Q. et al. A mitochondrial genome sequence of the Tibetan antelope (Pantholops hodgsonii). Genomics, proteomics & bioinformatics 3, 5–17 (2005).

Wang, Z. et al. Domestication relaxed selective constraints on the yak mitochondrial genome. Mol Biol Evol 28, 1553–1556 (2011).

Hassanin, A., Ropiquet, A., Couloux, A. & Cruaud, C. Evolution of the mitochondrial genome in mammals living at high altitude: new insights from a study of the tribe Caprini (Bovidae, Antilopinae). Journal of molecular evolution 68, 293–310 (2009).

Yu, L., Wang, X., Ting, N. & Zhang, Y. Mitogenomic analysis of Chinese snub-nosed monkeys: Evidence of positive selection in NADH dehydrogenase genes in high-altitude adaptation. Mitochondrion 11, 497–503 (2011).

Zhou, T., Shen, X., Irwin, D. M., Shen, Y. & Zhang, Y. Mitogenomic analyses propose positive selection in mitochondrial genes for high-altitude adaptation in galliform birds. Mitochondrion 18, 70–75 (2014).

Li, Y. et al. High altitude adaptation of the schizothoracine fishes (Cyprinidae) revealed by the mitochondrial genome analyses. Gene 517, 169–178 (2013).

Brown, W. M., George, M. & Wilson, A. C. Rapid Evolution of Animal Mitochondrial-DNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 76, 1967–1971 (1979).

Cameron, S. L., Lambkin, C. L., Barker, S. C. & Whiting, M. F. A mitochondrial genome phylogeny of Diptera: whole genome sequence data accurately resolve relationships over broad timescales with high precision. Syst Entomol 32, 40–59 (2007).

Nakatani, M., Miya, M., Mabuchi, K., Saitoh, K. & Nishida, M. Evolutionary history of Otophysi (Teleostei), a major clade of the modern freshwater fishes: Pangaean origin and Mesozoic radiation. BMC evolutionary biology 11, 177 (2011).

Mayden, R. L. et al. Reconstructing the phylogenetic relationships of the earth’s most diverse clade of freshwater fishes-order Cypriniformes (Actinopterygii: Ostariophysi): A case study using multiple nuclear loci and the mitochondrial genome. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution 51, 500–514 (2009).

Slechtova, V., Bohlen, J. & Tan, H. H. Families of Cobitoidea (Teleostei; Cypriniformes) as revealed from nuclear genetic data and the position of the mysterious genera Barbucca, Psilorhynchus, Serpenticobitis and Vaillantella. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution 44, 1358–1365 (2007).

Tang, Q. Y., Liu, H. Z., Mayden, R. & Xiong, B. X. Comparison of evolutionary rates in the mitochondrial DNA cytochrome b gene and control region and their implications for phylogeny of the Cobitoidea (Teleostei: Cypriniformes). Molecular phylogenetics and evolution 39, 347–357 (2006).

Froese, R. & Pauly, D. FishBase. World Wide Web electronic publication. www.fishbase.org, version (10/2015) (2015).

Zhu, S. Q. The Loaches of the Subfamily Nemacheilinae in China (Cypriniformes: Cobitidae). Nanjing: Jiangsu Scientific Technology Press (1989).

Wu, Y. & Wu, C. The Fishes of the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau. (Sichuan Publishing House of Science and Technology, 1992).

Wang, J. J. et al. The complete mitogenome sequence of a cave loach Triplophysa rosa (Teleostei, Balitoridae, Nemacheilinae). Mitochondrial DNA 23, 366–368 (2012).

Saitoh, K. et al. Mitogenomic evolution and interrelationships of the Cypriniformes (Actinopterygii: Ostariophysi): the first evidence toward resolution of higher-level relationships of the world’s largest freshwater fish clade based on 59 whole mitogenome sequences. Journal of molecular evolution 63, 826–841 (2006).

Broughton, R. E., Milam, J. E. & Roe, B. A. The complete sequence of the zebrafish (Danio rerio) mitochondrial genome and evolutionary patterns in vertebrate mitochondrial DNA. Genome research 11, 1958–1967 (2001).

Sawada, Y. Phylogeny and zoogeography of the superfamily Cobitoidea (Cyprinoidei, Cypriniformes). 65–223 (Hokkaido Univ, 1982).

Siebert, D. J. Interrelationships among families of the order Cypriniformes (Teleostei)-Unpubl.Ph.D. Thesis, City University of New York, New York, NY (1987).

Saitoh, K. et al. Evidence from mitochondrial genomics supports the lower Mesozoic of South Asia as the time and place of basal divergence of cypriniform fishes (Actinopterygii: Ostariophysi). Zool J Linn Soc-Lond 161, 633–662 (2011).

Liu, S. Q. et al. Phylogenetic relationships of the Cobitoidea (Teleostei: Cypriniformes) inferred from mitochondrial and nuclear genes with analyses of gene evolution. Gene 508, 60–72 (2012).

Mayden, R. L. et al. Inferring the Tree of Life of the order Cypriniformes, the earth’s most diverse clade of freshwater fishes: Implications of varied taxon and character sampling. J Syst Evol 46, 424–438 (2008).

He, D. K., Chen, Y. X. & Chen, Y. F. Molecular phylogeny and biogeography of the genus Triplophysa (Osteichthyes:Nemacheilinae) in the Tibetan Plateau inferred from cytochrome b DNA sequences. Prog Nat Sci 16, 1395–1404 (2006).

Lundberg, J. G. African-South American freshwater Wsh clades and continental drift: problems with a paradigm. In: Goldblatt, P. (Ed.), Biological Relationships between Africa and South America. 156–199 (New Haven, 1993).

Ruber, L., Kottelat, M., Tan, H. H., Ng, P. K. & Britz, R. Evolution of miniaturization and the phylogenetic position of Paedocypris, comprising the world’s smallest vertebrate. BMC evolutionary biology 7, 38 (2007).

Li, J. J. & Fang, X. M. Uplift of the Tibetan Plateau and environmental changes. Chinese Sci Bull 44, 2117–2124 (1999).

Harrison, T. M., Copeland, P., Kidd, W. S. F. & Yin, A. Raising Tibet. Science 255, 1663–1670 (1992).

Harrison, T. M., Copeland, P., Kidd, W. S. F. & Lovera, O. M. Activation of the Nyainqentanghla Shear Zone - Implications for Uplift of the Southern Tibetan Plateau. Tectonics 14, 658–676 (1995).

Li, J. J. et al. Late Miocene-Quaternary rapid stepwise uplift of the NE Tibetan Plateau and its effects on climatic and environmental changes. Quaternary Res 81, 400–423 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. Evidence for Adaptation to the Tibetan Plateau Inferred from Tibetan Loach Transcriptomes. Genome biology and evolution 7, 2970–2982 (2015).

Martin, A. P. & Palumbi, S. R. Body Size, Metabolic-Rate, Generation Time, and the Molecular Clock. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 90, 4087–4091 (1993).

da Fonseca, R. R., Johnson, W. E., O’Brien, S. J., Ramos, M. J. & Antunes, A. The adaptive evolution of the mammalian mitochondrial genome. BMC genomics 9, 119 (2008).

Hassanin, A., Ropiquet, A., Couloux, A. & Cruaud, C. Evolution of the Mitochondrial Genome in Mammals Living at High Altitude: New Insights from a Study of the Tribe Caprini (Bovidae, Antilopinae). Journal of molecular evolution 68, 293–310 (2009).

Wallace, D. C. Why do we still have a maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA? Insights from evolutionary medicine. Annu Rev Biochem 76, 781–821 (2007).

Mishmar, D. et al. Natural selection shaped regional mtDNA variation in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100, 171–176 (2003).

Garvin, M. R., Bielawski, J. P. & Gharrett, A. J. Positive Darwinian Selection in the Piston That Powers Proton Pumps in Complex I of the Mitochondria of Pacific Salmon. Plos one 6 (2011).

Sambrook, J. & Russell, D. W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, third ed. (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2001).

Iwasaki, W. et al. MitoFish and MitoAnnotator: a mitochondrial genome database of fish with an accurate and automatic annotation pipeline. Mol Biol Evol 30, 2531–2540 (2013).

Wang, M., Sun, S., Li, C. & Shen, X. Distinctive mitochondrial genome of Calanoid copepod Calanus sinicus with multiple large non-coding regions and reshuffled gene order: useful molecular markers for phylogenetic and population studies. BMC genomics 12, 73 (2011).

Abascal, F., Zardoya, R. & Telford, M. J. TranslatorX: multiple alignment of nucleotide sequences guided by amino acid translations. Nucleic acids research 38, W7–13 (2010).

Simmons, M. P. & Ochoterena, H. Gaps as characters in sequence-based phylogenetic analyses. Systematic biology 49, 369–381 (2000).

Xia, X., Xie, Z., Salemi, M., Chen, L. & Wang, Y. An index of substitution saturation and its application. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution 26, 1–7 (2003).

Darriba, D., Taboada, G. L., Doallo, R. & Posada, D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nature methods 9, 772 (2012).

Lanfear, R., Calcott, B., Ho, S. Y. & Guindon, S. Partitionfinder: combined selection of partitioning schemes and substitution models for phylogenetic analyses. Mol Biol Evol 29, 1695–1701 (2012).

Huelsenbeck, J. P. & Ronquist, F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 17, 754–755 (2001).

Ronquist, F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference and Model Choice Across a Large Model Space. Systematic biology 61, 539–542 (2012).

Rambaut, A., Suchard, M. A., Xie, D. & Drummond, A. J. Tracer v1.6, Available from http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/Tracer (2014).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313 (2014).

Yang, Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol 24, 1586–1591 (2007).

Hedges, S. B., Marin, J., Suleski, M., Paymer, M. & Kumar, S. Tree of life reveals clock-like speciation and diversification. Mol Biol Evol 32, 835–845 (2015).

Rannala, B. & Yang, Z. Inferring speciation times under an episodic molecular clock. Systematic biology 56, 453–466 (2007).

Cavender, T. M. Review of the fossil history of North American freshwater fishes. In: Hocutt, C. H. & Wiley, E. O. eds. Zoogeography of North American freshwater fishes. 699–724 (John Wiley & Sons, 1986).

Liu, J. & Chang, M. M. A new Eocene catostomid (Teleostei: Cypriniformes) from northeastern China and early divergence of Catostomidae. Sci China Ser D 52, 189–202 (2009).

Frickhinger, K. A. Fossilien atlas fishes [English translation 1995]. Mergus, Melle, Germany. 1088 pp (1991).

Zhou, J. J. A new Cobitis from the middle Miocene of Shanwang, Shandong. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 30, 71–76 (1992).

R Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL http://www.R-project.org/ (2013).

Pond, S. L. K., Frost, S. D. W. & Muse, S. V. HyPhy: hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Bioinformatics 21, 676–679 (2005).

Murrell, B. et al. Detecting individual sites subject to episodic diversifying selection. Plos Genet 8, e1002764 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Pilot projects (Grant No. XDB13020100). We are thankful to Dr Dekui He to help revise the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. contributed to fish sampling, experiments, data analysis and manuscript writing. Y.S. participated in the molecular experiments. C.F., K.Z., Z.S. and Y.Z. contributed to fish sampling. L.Y. contributed to data analysis. Y.W. and S.H. conceived and designed the experiments.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Shen, Y., Feng, C. et al. Mitogenomic perspectives on the origin of Tibetan loaches and their adaptation to high altitude. Sci Rep 6, 29690 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29690

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29690

This article is cited by

-

Age, growth, and energy storage of the subterranean fish Triplophysa rosa (Cypriniformes: Nemacheilidae) from Chongqing, China

BMC Ecology and Evolution (2023)

-

Adaptive evolution characteristics of mitochondrial genomes in genus Aparapotamon (Brachyura, Potamidae) of freshwater crabs

BMC Genomics (2023)

-

The first complete mitogenome of Acharax sp. (Protobranchia, Solemyida, Solemyidae): comparisons with other Solemyidae bivalves and deep-sea adaptive characteristics

Journal of Oceanology and Limnology (2023)

-

Divergent evolution of mitogenomics in Cetartiodactyla niche adaptation

Organisms Diversity & Evolution (2023)

-

Enlarged fins of Tibetan catfish provide new evidence of adaptation to high plateau

Science China Life Sciences (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.