Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO) reduction pathways are systematically studied on a (111) facet of the octahedral nickel (Ni85) nanocluster in the presence/absence of hydrogen. Thermodynamic (reaction free energies) and kinetic (free energy barriers and temperature dependent reaction rates) parameters are investigated to find out the most favoured reduction pathway for NO reduction. The catalytic activity of the Ni-nanocluster is investigated in greater detail toward the product selectivity (N2 vs. N2O vs. NH3). The previous theoretical (catalyzed by Pt, Pd, Rh and Ir) and experimental reports (catalyzed by Pt, Ag, Pd) show that direct N-O bond dissociation is very much unlikely due to the high-energy barrier but our study shows that the reaction is thermodynamically and kinetically favourable when catalysed by the octahedral Ni-nanocluster. The catalytic activity of the Ni-nanocluster toward NO reduction reaction is very much efficient and selective toward N2 formation even in the presence of hydrogen. However, N2O (one of the major by-products) formation is very much unlikely due to the high activation barrier. Our microkinetic analysis shows that even at high hydrogen partial pressures, the catalyst is very much selective toward N2 formation over NH3.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reduction of NO has attracted considerable attention in recent years due to the environmental pollutions and industrial applications1,2. NO is produced as a by-product during the combustion of hydrocarbons and is responsible for environmental (such as photochemical smog, acid rain, ozone depletion) and biological problems3,4,5. Therefore, the removal of NO is highly sought after and a major challenge for researchers. Extensive progress has been made over Pt6,7,8,9,10,11,12, Pd13,14,15, Rh16,17,18,19,20 and Ir21,22,23 metal surfaces for the catalytic conversion of NO to N2. However, the N-O bond dissociation is one of the most important steps and N-O can be dissociated via two pathways (i) direct N-O bond dissociation or (ii) indirect (hydrogenation followed by N-O bond dissociation). Earlier studies6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23 reported that direct N-O bond dissociation is not thermodynamically favourable over Pt6,7,8,9,10,11,12, Pd13,14,15, Rh16,17,18,19,20 and Ir21,22,23 metal surfaces, but possible from their hydrogenated products (NOH, HNO, HNOH, H2NO), which increases the possibility of unwanted by-products. Therefore, the relative selectivity of N2 vs. other products (N2O and NH3) varies from catalyst to catalyst. The reduction selectivity toward N2 formation is more dependent on the direct N-O bond dissociation kinetics. Hence the main objective of this work is to design an efficient catalyst to improve the N-O bond dissociation kinetics to increase the N2 production selectivity.

NO reduction reactions have been studied mainly over precious metal based catalysts. However, considerable efforts have been made to reduce the cost of metal catalysts and among all the low-cost based metal-catalysts, Ni is the most effective catalyst due to the easy availability of valence shell d-electrons24,25,26,27,28,29,30. Experimental and theoretical studies have been carried out for NO reduction reactions catalysed by Ni-catalysts31,32,33,34,35,36,37 and it is reported that NO undergoes dissociative adsorption over Ni-catalyst38, resulting in the formation of N2 as a major product. However, the role of hydrogen (reducing agent) is not considered in any of these studies and thus a vis-à-vis comparison cannot be made between the direct and indirect N-O bond activation processes. Therefore, it is very important to find out whether Ni-catalyst could trigger the direct N-O bond dissociation or favours the indirect N-O bond dissociation as reported for noble metal based catalysts6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23.

Apart from different metal based catalysts, the surface morphology and size of the metal catalyst play important roles in the bond scission process, which in turn control the catalytic activity of a metal catalyst. In this context, metal nanoclusters surrounded by well-defined facets show better catalytic activities compared to their bulk surfaces. Metal nanoclusters enclosed by multi-facets are very noble catalysts and are reported to be very promising for electro-catalytic reactions39,40,41 due to the presence of high surface unsaturation. Many theoretical studies have been reported on small size metal nano-clusters42,43,44,45 to understand their catalytic activities toward nitric oxide reduction. However, the size of the nanoclusters is very important for catalytic reactivity due to their finite-size effects46,47,48,49,50,51 and well-defined facets. These low-coordinated sites have higher d-band energies, which actually increase their reactivity42,43. To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports on NO reduction on a well-defined nanocluster based catalyst. Therefore, to understand the activity of the nanocluster, it is necessary to model a nanocluster surrounded by well-defined facets. The nanocluster with octahedral shape is one of the most stable forms due to its high symmetry52,53. In fact, the Ni(111) surface is mainly observed in the experimentally synthesized Ni-nanoclusters54,55,56. Hence we have modelled a ~1 nm size of octahedral nickel nanocluster (Ni85) enclosed by well-defined low index facets [eight (111) facets] to understand the NO reduction activity (Fig. 1).

It is also very important to study the complete catalytic process in the presence and absence of hydrogen to understand the underlying NO reduction reaction mechanism to improve the product selectivity. The N2 production selectivity can be significantly improved if the reduction mechanism goes through the following two steps: direct NO dissociation [*NO → *N + *O] followed by N2 formation [*N + *N → *N2]. Species are denoted with an asterisk (*) while adsorbed on the surface. But then there are possibilities of by-product formation, such as N2O formation: *NO + *N → *N2O. Koper et al.57 reported that NH3 is formed via an indirect N-O bond dissociation process. In that case hydrogenation of NO (formation of *HNO and *H2NO intermediates) followed by N-O bond dissociation favours the formation of NH3. Cuesta et al.58 found *HNOH as the predominant intermediate for NH3 formation. Previous theoretical studies reported Ir(211) selectively produces N2, while Pt(211) produces8 N2 and N2O but they did not consider the role of hydrogen. Carrie et al.6 studied NO reduction on the Pt (111) surface to understand the N2O formation as a major product observed experimentally at low temperatures59,60. In spite of several studies, direct N-O bond dissociation is calculated to be the least favourable pathway in the presence/absence of hydrogen gas.

Here we have systematically studied the complete NO reduction pathways on a Ni(111) facet of the nanocluster to find out the most favoured pathway(s) to control the product selectivity. Microkinetic analysis is performed to understand the role of temperature and partial pressure towards the product selectivity. The catalytic activity of the nanocluster is compared with the bulk Ni(111) surface to have a vis-à-vis comparison for the NO reduction reaction. For comparison with a noble metal catalyst, the catalytic activity is compared with that of bulk Pt(111). An attempt has been made to understand the excellent catalytic activity of the nanocluster toward NO reduction and product selectivity compared to any other catalysts reported previously.

Results

Adsorption

Four different catalytic sites (Fig. 1) are present on the (111) facet of the nanocluster: (i) top, (ii) bridge, (iii) hexagonal close packed (hcp) and (iv) face centred cubic (fcc). The relative stabilities of the adsorbed conformers are studied at four possible sites and the most stable conformer is considered for further study.

Intermediates adsorbed on the Ni(111) facet of the nanocluster are presented in Fig. 2. The most preferred binding sites of the intermediates and their respective binding energies are presented (Fig. 2) and compared with previous theoretical studies on Ni(111)35,36,61 and Pt(111)6 surfaces. The adsorption energies (Ead) for all possible adsorbates are calculated using the following equation:

Site preference, binding energy (eV) of the most stable adsorbates on the (111) facet of the Ni85 naocluster.

The sites preferences and binding energies of the respective adsorbates are compared with previous reports on Pt(111)6 and Ni(111)35,36,61 surfaces. Yellow, cyan, red and blue spheres represent N, H, O and Ni, respectively.

where Ecluster-species is the total energy of the cluster with adsorbed species, Ecluster is the energy of the nickel cluster and Especies is the energy of the intermediate species. The binding energies are in very much agreement with previous studies6,7,35,36,37 though some of our calculated binding energies are higher than the previous reported values. The differences in adsorption energies compared to previous theoretical values could be due to the excellent catalytic activity of the Ni-nanocluster. The adsorption patterns of some of the important intermediates (*NO, *N2O, *N2, *NOH, *HNO, *H2NOH and *NH3) are discussed and compared to previous experimental and theoretical reports.

*NO

*NO prefers to be adsorbed at the fcc site (Fig. 2) of Ni(111) through its N atom with an adsorption energy of −3.08 eV. Wu et al.35 reported that the *NO molecule prefers to occupy the fcc site of the Ni(111) surface with an adsorption energy of −2.46 eV. It has been experimentally38 as well as theoretically35,62 reported that NO prefers to be adsorbed through its N atom as it has more vacant orbitals than an O-atom. The vibrational frequency of the *N-O bond (1460–1543 cm−1) while adsorbed at the fcc site of Ni(111) surface is characterized38 using RAIRS, EELS and PED and agrees well with our calculated value of 1530 cm−1. Therefore, our results are in very much agreement with previous reports on binding energy and vibrational frequency35,36,37.

*N2O

*N2O prefers (Fig. 2) to be adsorbed at a top site of the Ni(111) facet. A theoretical study63 on the (111) terrace of the high index Ni(755) surface reported a <N-N-O bond angle of 180° and Ni-N, N-N and N-O bond distances of 1.84, 1.15 and 1.20 Å, respectively. They are in very much agreement with our calculated (Fig. 2) <N-N-O bond angle of 179.66° and Ni-N, N-N and N-O bond distances of 1.83, 1.14, 1.20 Å respectively. Using XPS and TPD studies, they reported that *N2O weakly adsorbed on the Ni(111) surface through its N-atom64,65. Thus, the calculated structural parameters are in very much agreement with the previous report35. This suggests that our study on the Ni(111) facet is in very close agreement with previous experimental reports on the high index Ni(755) surface64,65.

*NOH and *HNO

In the presence of hydrogen, *NO can react with *H to form *NOH and *HNO. *NOH adsorbs strongly at the fcc-site (Fig. 2) through its N atom with adsorption energy of −4.27 eV. On the other hand, *HNO binds in a di-sigma manner (Fig. 2) with an adsorption energy of −4.56 eV. Their binding preferences are very much in agreement with previous findings6,7,13.

*N2

*N2 binds perpendicular to the top site of the (111) facet of the nanocluster (Fig. 2) with adsorption energy of −0.23 eV. The calculated Ni-N and N-N bond distances are 1.78 Å and 1.12 Å respectively. The N-N bond distance is slightly lengthened while adsorbed on the surface compared to the N-N distance (1.10 Å) in the N2 gas molecule, suggesting that the interaction is very weak between the surface and gas molecule. Previous studies35,36 on the Ni(111) surface reported that the top site is the most favoured position for N2 adsorption. Using infrared reflection absorption spectroscopy, Yoshinobu et al.66 reported that *N2 adsorbs perpendicular on the Ni(111) surface with an adsorption energy of −0.36 eV.

*NHx (x = 1–3)

*NHx containing species (Fig. 2) can be formed during the course of reaction. These intermediates (*NH, *NH2 and *NH3) are most stable at the fcc, bridge and top sites with Ni-N bond distances of 1.81, 1.91 and 2.01 Å respectively (Fig. 2). *NH and *NH2 bind strongly, whereas *NH3 binds weakly on the Ni-nanocluster surface. The calculated adsorption energies are −5.05 eV, −3.02 eV and −0.51 eV for *NH, *NH2 and *NH3 respectively. Sergey et al.61 reported *NH3 prefers to bind on the top site of the Ni(111) surface, which agrees well with our finding. The weak adsorption of *NH3 suggests the easy desorption of NH3 from the catalyst surface, which in turn reduces the possibility of surface poisoning.

*H2NOH

*H2NOH can be formed via hydrogenation at the N- and O- sites of *HNOH and *H2NO. *H2NOH adsorbs on the top-bridge position by its N- (Ni-N = 1.97 Å) and O atoms (Fig. 2).

It is interesting to find out that adsorption energy decreases (Fig. 2) from NO to higher hydrogenated products implying that the interactions are weaker for higher hydrogenated products.

Reaction Free Energy and Activation Barriers

The reaction free energies are calculated from the total energy difference between the products and reactants. Thus negative free energy suggests the exergonic nature of the reaction, whereas positive reaction energy suggests the endergonic nature of the reaction. Activation barriers are calculated from the energy differences between the transition and initial states.

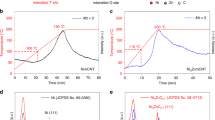

*N2 and *N2O Formation

The direct N-O bond dissociation (Fig. 3) can lead to the formation of important products such as *N2 and *N2O.

Reaction Scheme.

Reaction free energies (eV) and activation barriers (eV, in parenthesis) are presented for all the possible elementary steps for NO reduction over the (111) facet of the Ni85 nanocluster. Our calculated respective values are compared with previous reports on NO reduction over Ni(111)35 and Pt(111)6,7 bulk surfaces.

The direct N-O bond dissociation (step 1) is a downhill process (−0.69 eV) with an activation barrier of 1.03 eV. The *N-O bond distance is 1.22 Å, which is higher than the N-O bond distance (1.15 Å) in the gas (NO) molecule. This suggests that the gas molecule gets activated during the adsorption process. The previously calculated N-O bond dissociation barriers are 1.49 eV36 and 1.58 eV35 on Ni(111) surfaces, which are far higher than our calculated barrier of 1.03 eV. In fact, the higher *N-O bond distance (1.22 Å), compared to previous report (1.18 Å)37, suggests the excellent catalytic activity of the nanocluster. Earlier reports of N-O bond dissociation barriers on bulk Pt(111) surfaces are 2.60 eV8 and 2.32 eV6, respectively, which are considerably higher than our calculated barrier of 1.03 eV. Therefore, Ni85 nanocluster is certainly an efficient catalyst for the direct N-O bond activation reaction.

The formation of *N2 (step 2) from the atomic nitrogens (*N) is exergonic by −0.19 eV with an activation barrier of 1.05 eV. Wu et al.35 reported an activation barrier of 2.34 eV for the same step on the bulk Ni(111) surface. Carrie et al.6 studied the *N2 formation on Pt(111) surface and reported a free energy barrier of 1.55 eV. Therefore, the Ni85 nanocluster shows excellent catalytic activity toward *N2 formation compared to noble metal based catalysts.

*N2 formation is possible via another pathway where *N2O (step 3) formation takes place, followed by *N2O dissociation (step 4). The *N2O formation is highly endergonic (1.62 eV) with a free energy barrier of 2.54 eV, whereas *N2O dissociation is highly exergonic (−2.58 eV) with an activation barrier of 0.39 eV. Wu et al.35 reported the *N2O formation barrier of 1.74 eV (step 3) on the Ni(111) surface. Carrie et al. reported the *N2O formation and dissociation barriers6 of 1.18 eV and 0.61 eV on Pt(111). The calculated barrier for *N2O formation is significantly higher than the previous reports on Ni(111) and Pt(111) surfaces.

Wu et al.35 studied the first three steps of NO reduction on the Ni(111) surface as follows: (i) *NO dissociation, (ii) *N2 and (iii) *N2O formation. The calculated activation barriers are 1.58 eV (*NO dissociation), 2.34 (*N2 formation) and 1.74 eV (*N2O formation) respectively. Similarly Carrie et al.6, reported activation barriers of 2.32 eV (*NO dissociation), 1.55 eV (*N2 formation), 1.18 eV (*N2O formation) and 0.61 eV (*N2O dissociation) over Pt(111). Therefore, the previous reports show *N2O formation is favourable over *N2 formation, whereas our study shows *N2 formation is favourable over *N2O formation. However, *N2O dissociation is very favourable (step 4) in all the cases. But on the Ni85 cluster’s surface, the *N2O formation is very unlikely to happen due to the high activation barrier of 2.54 eV. Therefore, our nanocluster shows excellent catalytic activity toward *N2 formation, compared to earlier reports6,8,35,36,37. Hence, the dissociation of the N-O bond followed by N-N bond formation (*NO → *N → *N2) is the most favourable pathway in the absence of hydrogen.

*NH3 Formation

Hydrogen is used as a reducing agent for NO reduction. The dissociation of hydrogen toward atomic hydrogens (*H2 → *H + *H) is highly exergonic (−1.07 eV) with an activation barrier of 0.02 eV. The dissociative adsorption of hydrogen on the Pt (111) bulk surface is reported to be exergonic by −0.87 eV with an activation barrier of 0.00 eV6. The activation barrier for hydrogen dissociation on Ni(111) surface is very much comparable with that on the Pt(111) surface. However, the reaction is highly exergonic on the Ni-surface compared to the Pt(111) surface25,67. Therefore, the Ni-nanocluster is a promising candidate for the hydrogenation reaction.

The first hydrogenation on *N (step 5, *NH formation) has an activation barrier of 0.51 eV though the reaction is exergonic by −0.11 eV. In contrast, the second hydrogenation (step 6) for the formation of *NH2 is endergonic by 0.50 eV with an activation barrier of 1.01 eV. The formation between *NH2 (step 6) and *N2 (step 2) can be very competitive as both the reaction steps (Fig. 3) have comparable free energy barriers (1.01–1.05 eV). However, the third hydrogenation (step 7, *NH3 formation) has an activation barrier of 0.49 eV with reaction free energy of −0.01 eV, suggesting that the *NH3 formation is very much favourable.

Hence, in the presence of hydrogen, *NO dissociation could lead to competition between *N2 and *NH formation. The calculated activation barriers show that *NH formation (barrier = 0.51 eV) is more favourable than *N2 formation (barrier = 1.05 eV). However, *NH2 formation (barrier = 1.01 eV) is not much favourable compared to *N2 formation (barrier = 1.05 eV). But, our reaction thermodynamics shows, *N2 formation is highly exergonic (−0.19 eV) compared to *NH2 formation (0.50 eV). Therefore, *N2 formation is a spontaneous process where as *NH2 formation is not thermodynamically favourable. Even the *NH (*NH → *N + *H) dissociative barrier (Fig. 3) is calculated to be 0.62 eV with a reaction energy of 0.11 eV, indicating the tendency of *NH to decompose to *N instead of hydrogenation to *NH2. Therefore *N2 formation is very much favourable, compared to ammonia formation even in the presence of hydrogen.

The hydrogenation at *NO on the Pt(111) surface leads to the indirect dissociation of the N-O bond, which in turn reduces the selectivity of *N2 formation over *NH3 formation68,69. Surprisingly, we find that the direct N-O bond dissociation barrier is lower compared to the indirect (*N-OH and *HN-O) bond dissociation barrier on the Ni(111) facet of the nanocluster. Therefore, on the Ni-nanocluster surface, *NO can be reduced to *N2 even in the absence of hydrogen, which minimizes the possibility of unwanted by-products (*NH3 and *N2O) formation.

*N2O can also be formed (Fig. 3) by the direct combination of *NO and *NH (step 8) followed by the dissociation of *ONNH (step 9).

The formation of *ONNH from *NO and *NH (step 8), is highly endergonic (1.38 eV) with an activation barrier of 1.38 eV. However, the dissociation of *ONNH (step 9) leads to the formation of *N2O, which is mildly endergonic (0.06 eV), with an activation barrier of 1.22 eV. But *N2O dissociation is a spontaneous process with an activation barrier of 0.39 eV (step 4). Thus, *N2O formation is very unlikely due to the high activation barrier.

*NO Hydrogenation

First Hydrogenation and Dissociation steps

In the hydrogenation pathways (Fig. 3), *NO can be hydrogenated to form *NOH and *HNO respectively. Here, we have studied all the hydrogenated intermediates (Fig. 3) to find out the thermodynamic and kinetic feasibility of such reactions.

The *NO hydrogenation reactions (step 10 and 11) are endergonic by 0.94 eV (step 10) and 1.07 eV (step 11) with activation barriers of 1.28 eV (step 10) and 1.83 eV (step 11), respectively. Therefore, hydrogenation at the O atom is more favourable over the N atom. The relative stabilities of the isomers (*NOH and *HNO) show that *NOH is more stable (by 0.15 eV) over *HNO. Previous reports also show that NO undergoes hydrogenation at O-7 and N- atoms6 though favourable at the O atom.

The reaction energies for N-O bond dissociation of the hydrogenated species are −1.28 eV (step 12) and −1.81 eV (step 13) and activation barriers are 0.88 eV and 0.76 eV for *NOH and *HNO respectively. Therefore, hydrogenation on NO (Fig. 3) lowers the N-O bond dissociation barrier. Our study shows that *HNO has a lower N-O bond dissociation barrier than *NOH. As *NH and *N are the two competitive intermediates for *NH3 and *N2 formation, therefore N-O dissociation barriers of *HNO and *NOH give an idea about the selectivity of product formation. Carrie et al.6 reported that the dissociation barrier of the N-O bond is less in *NOH than in *NO on the Pt (111) surface, suggesting that *N2O is the predominant product. In fact, all the previous studies6,7 show indirect N-O bond dissociation is favourable over direct N-O bond dissociation, whereas we find direct N-O bond dissociation is favourable over indirect N-O bond dissociation. Therefore, the Ni85 nanocluster is an efficient and a selective catalyst for *N2 formation over *N2O and *NH3 formation.

Second Hydrogenation and Dissociation steps

The *NOH can further undergo hydrogenation for the formation of *HNOH (step 14). It has an activation barrier of 1.24 eV with reaction free energy of 0.71 eV. Similarly *HNO can undergo hydrogenation for the formation of *HNOH (step 15) and *H2NO (step 16). *HNOH formation is endergonic by 0.29 eV with an activation barrier of 0.53 eV and *H2NO formation is endergonic by 0.32 eV with an activation barrier of 0.91 eV. Hence, hydrogenation on *HNO is thermodynamically and kinetically favourable over hydrogenation on *NOH.

Now, both the hydrogenated intermediates (*HNOH and *H2NO) can undergo N-O bond dissociation to produce *NH and *NH2 respectively (step 17–18). The dissociation reactions (step 17–18) are highly exergonic and have low activation barriers and are easy to dissociate.

Our results show that *NO prefers to be hydrogenated at the O-centre to form *NOH followed by hydrogenation at the N-centre to form *HNOH, which support the preference of hydrogenation at the O-centre over the N-centre. The preference of hydrogenation at the O-centre is also found for the first hydrogenation of *NO (*NO + *H → *NOH). Andre et al.7 also reported that *NOH and *HNOH are the favourable intermediates over *HNO and *H2NO intermediates. Therefore, the most favourable pathway for *NH3 formation is *NO → *NOH → *HNOH → *NH, whereas the least favourable pathway is *NO → *HNO → *HNOH → *NH.

Third Hydrogenation and Dissociation steps

The third hydrogenation (step 19–20) on *NO can take place for the formation of *H2NOH and *H2NOH. Hydrogenation at the N-centre (step 19) is mildly endergonic by 0.05 eV with an activation barrier of 0.89 eV, whereas hydrogenation at the O-centre (step 20) is mildly endergonic by 0.08 eV with an activation barrier of 0.24 eV. Interestingly, hydrogenation becomes more and more favourable as the number of hydrogens increases.

The N-O dissociation from *H2NOH is highly exergonic (−2.14 eV, step 21) with an activation barrier of 0.32 eV. However, the N-O bond dissociation barrier is lower in *HN-OH (0.14 eV) than in *H2N-O, indicating that *HNOH is likely to dissociate (step 17). Therefore, the N-O bond dissociation barriers are lower and lower for the higher hydrogenated intermediates.

The N-O bond distances in the intermediate species support such a trend. The calculated N-O bond distances are 1.22 Å, 1.40 Å, 1.43 Å and 1.44 Å in *NO, *NOH, *HNOH and *H2NOH respectively, suggesting that N-O bond dissociation is very likely for the higher hydrogenated products.

After going through all the possible hydrogenation and non-hydrogenation pathways, we find N2 formation is highly favourable over NH3 formation. Therefore, the most favourable route toward N2 formation is *NO → *N → *N2, whereas *NO → *ONNH → *N2O → *N2 is the less favourable route. The most favourable route toward NH3 formation is *NO → *NOH → *HNOH → *NH → *NH2 → *NH3 and the less favourable routes are *NO → *HNO → *HNOH → *NH → *NH2 → *NH3 and *NO → *HNO → *HNOH → *H2NOH → *NH2 → *NH3.

Non-favourable Pathways

Along with the most favourable pathways, we have studied some other possible pathways, which are discussed as follows.

*NOH could react with *NO to form *ONNOH (step 22) with an activation barrier of 1.99 eV. As the barrier is very high, this reaction is very unlikely to proceed. *ONNOH has a dissociation barrier of 0.59 eV for the formation of *N2O (step 23). The other possibility is *NO reacting with *HNO for the formation of a N-N bond (step 24; via *ONNHO) followed by N-O bond dissociation (step 25). The N-N bond formation step is highly endergonic by 1.77 eV with an activation barrier of 2.37 eV and thus is very unlikely to happen. However, the N-O bond dissociation (step 25) is highly exergonic (−1.66 eV) with an activation barrier of 0.89 eV. The calculated activation barriers are 2.37 eV and 0.89 eV for N-N bond formation and N-O bond dissociation steps respectively. The lower activation barrier for the formation of *ONNOH over *ONNHO is due to the stability (by 0.15 eV) and strong adsorption energy (by 2.58 eV) of *ONNOH species compared with *ONNHO. The lower activation barrier for N-O bond dissociation in *ONNOH over *ONNHO is attributed to the longer N-O bond distance (1.42 Å) in *ONNOH than in *ONNHO (1.32 Å). Such higher activation barrier for *ONNHO (2.04 eV) formation over *ONNOH formation (1.42 eV) has been reported previously on the Pt(111) surface7.

Kinetic Analysis

From the elementary pathways, we discover that many pathways are possible for a N-O bond dissociation reaction. The Gibbs free energy versus reaction coordinate gives an overall idea to locate the minimum energy pathway from several possibilities. The roles of surface coverage, gas phase partial pressures of reactant and product and reaction temperature cannot be fully understood from the Gibbs free energy calculations. These experimental parameters can provide further insights to find out the most favoured pathway for the NO reduction reaction. Thus, we have done a detailed microkinetic analysis based on our preliminary DFT results to understand the roles of surface coverage, partial pressures of reactants/products and reaction temperatures toward the reaction kinetics. The forward (ki) and backward (k−i) rate constants for all the elementary steps are calculated using the following equation:

where kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature, h is the Plank constant. Here qI and qF are vibrational partition functions for the initial and final state structures and ΔG‡ is the Gibbs free energy barrier for the initial and final state of the elementary reaction. The vibrational partition functions (q) are calculated using the following equation:

where υi are the vibrational frequencies. All the exergonic reactions are assumed to be irreversible. Hence only forward steps are considered. For endergonic reactions, both the forward and backward steps are considered while developing the microkinetic model. ki and k−i are used for the forward and backward reaction steps respectively for the i-th step. The details of the microkinetic model are given in the Supporting Information.

Here, using the mickokinetic model, we would like to understand the role of hydrogen partial pressure toward the hydrogenation of NO. In the presence of high hydrogen partial pressures, we would like to study whether or not *NO will favour hydrogenation over *N-O direct dissociation.

As the experimental NO reduction temperature ranges from 300 K to 500 K68,69, the rate constants (Table 1) are calculated in the same temperature range (300 K to 500 K). The rate constants improve significantly as we increase the temperature. At 300 K, the ratio between the rate constants (k10/k11) is ~109 for *NO hydrogenation at O- and N-sites respectively. Hence, *NOH formation is highly favourable over *HNO formation (*NO + *H → *NOH and *NO + *H → *HNO). The higher possibility of *NOH formation can be further confirmed from the surface coverage (Θ) study. The surface coverage ratio of the ΘNOH/ΘHNO (see Supporting Information for details) is calculated using the steady state approximation70, where the rates of production and decomposition are assumed to be equal. Therefore, ΘNOH and ΘHNO are calculated considering their equal rate of formation and decomposition in the complete reaction pathway. The ΘNOH/ΘHNO ratio is calculated to be 1.78, suggesting that the hydrogenation of *NO proceeds through the NOH intermediate, rather than through the *HNO intermediate. Surprisingly, the ratio between the forward and backward rate constants (k10/k11: ~109) is very high compared to their coverage ratio (1.78). The large difference is due to the high dissociation kinetics of *NOH (k−10) compared with *HNO (k−11). This is very much consistent with the previous trend observed from the relative energetics and activation barriers study, where we find hydrogenation at the O-centre is preferred over the N-centre.

However, hydrogenation at the N- and O- (of NO) is very important as hydrogenation at *N and O* sites will favour the formation of *NH3 and *N2 respectively, which in turn decides the product selectivity. The dissociation of *NOH leads to the formation of *N, whereas *HNO leads to the formation of *NH. *NH can be further hydrogenated for the formation of *NH3, whereas *N can undergo either hydrogenation or nitrogenation toward the formation of *NH3 and *N2 respectively. Thus, it is very important to understand that these hydrogenated pathways improve the product (*N2 vs. *NH3) selectivity.

Here ΘNOH/ΘHNO ratio implies the partial pressure ratio of NO and H2. Several ratios of partial pressures of NO/H2 are used to understand their roles toward the product selectivity. The surface coverage ratios of ΘNOH/ΘHNO are calculated for different partial pressure ratios of pNO/pH2. The calculated ΘNOH/ΘHNO are 5.53 × 10−02, 1.59 × 10−01, 3.13 × 10−01, 6.41 × 10−01, 1.77 × 1000, 4.98 × 1000, 1.22 × 1001, 3.51 × 1001 and 3.92 × 1002 for 500, 40, 12, 4, 1, 0.25, 0.08, 0.025, 0.002 atmospheres of partial pressure (pNO/pH2) respectively. Therefore, *NOH coverage increases with increasing partial pressure of hydrogen, which further improves the product selectivity (*N2 formation).

From the DFT calculated parameters (Gibbs free energy and activation barriers) and the rate constant of the reaction analysis, we have already proposed that *N2 is the predominant product over *NH3 in the presence and absence of hydrogen. We find the spontaneous formation of *N2 with lower activation barrier and the exergonic behaviour of *NH2 dissociation with low activation barrier are the underlying reasons for the *N2 formation with higher selectivity. However, we wonder whether increasing hydrogen partial pressures can turn the selectivity toward *NH3? Therefore, after cropping the crucial steps from the complete microkinetic model, we have shown the effect of external hydrogen partial pressure toward the product selectivity. The small and effective microkinetic model is developed considering the following steps: (i) , (ii)

, (ii)  , (iii)

, (iii)  and (iv)

and (iv) .

.

Therefore, the rate of formation of N2 and NH2  can be written as follows (see Supporting Information for details):

can be written as follows (see Supporting Information for details):

Several ratios of partial pressures of NO/H2 are used to understand their role toward the product selectivity. The calculated  value is ≈6.77 × 1035 when the partial pressure ratio (pH2/pNO) of 500:1 is used. Therefore, our results suggest that even with extreme hydrogen partial pressures, N2 is the predominant product.

value is ≈6.77 × 1035 when the partial pressure ratio (pH2/pNO) of 500:1 is used. Therefore, our results suggest that even with extreme hydrogen partial pressures, N2 is the predominant product.

However, under the 1:1 partial pressure ratio of NO and H2, ΘNOH/ΘHNO is found to be 1.78. Therefore, there could be a possibility of the reaction proceeding through the *HNO intermediate. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the extent of possibility for proceeding the reaction further from the *HNO intermediate. The ratio of rate constants (k5/k2) for  and

and  is 1.58 × 1009, implying that the *NH formation is favourable over *N2. However, the ratio of rate constants (k−5/k6) for *NH dissociation

is 1.58 × 1009, implying that the *NH formation is favourable over *N2. However, the ratio of rate constants (k−5/k6) for *NH dissociation  and *NH2 formation

and *NH2 formation  is 4.17 × 1006, suggesting the tendency of *NH to decompose to *N instead of hydrogenation to *NH2. Therefore, it does not matter whether the reaction proceeds through the *HNO intermediate or not as it dissociates into *NH and *O (*HNO → *NH + *O). Interestingly, further hydrogenation on *NH is highly unfavourable (*NH + *H → *NH2) compared to *NH decomposition (*NH → *N + *H). Therefore, the Ni85 nanocluster shows excellent catalytic activity toward high product (N2) selectivity.

is 4.17 × 1006, suggesting the tendency of *NH to decompose to *N instead of hydrogenation to *NH2. Therefore, it does not matter whether the reaction proceeds through the *HNO intermediate or not as it dissociates into *NH and *O (*HNO → *NH + *O). Interestingly, further hydrogenation on *NH is highly unfavourable (*NH + *H → *NH2) compared to *NH decomposition (*NH → *N + *H). Therefore, the Ni85 nanocluster shows excellent catalytic activity toward high product (N2) selectivity.

In the earlier sections, we have shown that *NOH coverage increases with increasing partial pressure of hydrogen. This in fact improves the formation of *N2. But with increasing of hydrogen partial pressures, does the formation of higher hydrogenated products (*HNOH and *H2NO) increase or not? Moreover, do such higher hydrogenated products also show greater selectivity towards the *N2 formation over *NH3 formation or not? The rate constants ratio [(k14 + k15)/k16] for the formation of *HNOH (*NOH + *H → *HNOH, *HNO + *H → *HNOH) and *H2NO is 5.88 × 1006, implying that *HNOH is the major product. Now, after N-O bond dissociation, *HNOH and *H2NO lead to the formation of *HN and *NH2, respectively. Interestingly, we already found *NH favours the formation of *N2 over *NH3.

Therefore, our study shows that the Ni85 nanocluster can efficiently and selectively reduce nitric oxide toward nitrogen even in the presence of high hydrogen partial pressure. Moreover, the most favourable pathway for *N2 formation is *NO → *N → *N2, whereas the least favourable pathway for *N2 formation is *NO → *ONNH → *N2O → *N2. Our results on the Ni-nanocluster are very much promising for product selectivity compared to previous experimental and theoretical reports on noble metal based catalysts (Pt, Pd, Rh, Ag, Pd).

Discussions

DFT calculations have been performed to understand the nitric oxide reduction reaction over (111) facet of the octahedral nickel nanocluster (Ni85) enclosed by well-defined facets. Our results on the Ni-nanocluster show that direct N-O bond dissociation is thermodynamically as well as kinetically very much favourable even in the presence of hydrogen, which is completely opposite to earlier experimental and theoretical reports on noble metal based catalysts (Pt, Pd, Rh, Ag), where indirect N-O bond dissociation (from their hydrogenated products: NOH, HNO, HNOH, H2NO) is favourable over direct N-O bond dissociation. Hence, the product selectivity (N2 vs. N2O/NH3) increases on a Ni-nanocluster surface, whereas selectivity decreases on noble metal surfaces. The NO reduction reaction on Ni(111) bulk surfaces is reported by several groups, but no one has studied the reduction reaction in the presence of the hydrogen. Thus, a vis-à-vis comparison could not be made. The lower *N-O bond dissociation and N-N bond formation barriers make the Ni85 cluster an efficient and a selective catalyst toward NO reduction for N2 formation. In the presence of hydrogen, the reaction might proceed through *NOH or higher hydrogenated intermediates, but such intermediates easily dissociate into *NH or *N, which in turn favours *N2 formation over *NH3. Our microkinetic analysis shows that even with extreme hydrogen partial pressures, *N2 formation is favourable over *NH3. Thus, the product selectivity towards N2 does not change even under high hydrogen partial pressures on a Ni-nanocluster surface, which is again completely opposite to earlier experimental and theoretical reports on noble metal based catalysts (Pt, Pd, Rh, Ag). Hence, we report that nickel based nanoclusters could be very promising catalysts for the efficient and selective reduction of nitric oxide to nitrogen.

Methods

The first-principles calculations are performed using the projected augmented wave (PAW) method71, as implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)72,73,74. The exchange-correlation potential is described by using the generalized gradient approximation of Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (GGA-PBE)75. The projector augmented wave (PAW) method71 is employed to treat interactions between ion cores and valance electrons. The structure optimization is based on the conjugate gradient-minimization scheme under a spin polarization consideration. Our calculated magnetic value shows that each nickel has a magnetic moment of 0.71 μB which is in very much agreement with the previously reported value of 0.69 μB25. For the consideration of van der Waals interactions, we have used Grimme’s D3-type of semiempirical method for dispersion energy correction76,77. But, we have listed the non-dispersion corrected values for a vis-à-vis comparison with earlier reports, as they have not included dispersion correction in their calculations. However, we have given both the dispersion-corrected and non-corrected values in the Supporting Information. A 22 × 22 × 22 Å3 cubic supercell is used to optimize the metal clusters to rule out the possibility of interaction of periodically repeated clusters. The Brillouin zone is sampled using gamma k-point (1 × 1 × 1). The total energy improved by 0.0001 eV when k-points are increased to 2 × 2 × 2. As the box size is quite high therefore we have used gamma point for our calculations. Plane wave with a kinetic energy cut off of 470 eV is used to expand the electronic wave functions. All the atoms are relaxed for the full structural relaxation. The climbing nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) method78 is used to locate the transition states. Six intermediate images are used in each CI-NEB pathway. Vibrational frequencies for the initial, transition and final states of the reactions are calculated and the transition state is confirmed from the presence of one imaginary frequency along the reaction coordinate. Zero-point energy (ZPE) is calculated from the following equation:

where h is the Planck constant and υi is the frequency of the ith vibrational mode.

The reaction free energies (ΔG) and activation barriers (ΔG‡) are calculated using zero point energy (ZPE) and entropy corrections. The species are denoted with asterisk (*) while adsorbed on the surface.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Mahata, A. et al. Octahedral Ni-nanocluster (Ni85) for Efficient and Selective Reduction of Nitric Oxide (NO) to Nitrogen (N2). Sci. Rep. 6, 25590; doi: 10.1038/srep25590 (2016).

References

Duca, M. et al. Selective catalytic reduction at quasi-Perfect Pt(100) domains: A universal low-temperature pathway from nitrite to N2 . J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 10928–10939 (2011).

Yang, J., Calle-Vallejo, F., Duca, M. & Koper, M. T. M. Electrocatalytic reduction of nitrate on a Pt electrode modified by p-Block metal adatoms in acid solution. ChemCatChem 5, 1773–1783 (2013).

Paredis, K. et al. Evolution of the structure and chemical state of Pd nanoparticles during the in situ catalytic reduction of NO with H2 . J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 13455–13464 (2011).

Liu, Z. M., Li, J. H. & Woo, S. I. Recent advances in the selective catalytic reduction of NOx by hydrogen in the presence of oxygen. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 8799–8814 (2012).

Privett, B. J., Shin, J. H. & Scoenifisch, M. H. Electrochemical nitric oxide sensors for physiological measurements. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 1925–1935 (2010).

Farberow, C. A., Dumesic, J. A. & Mavrikakis, M. Density functional theory calculations and analysis of reaction pathways for reduction of nitric Oxide by hydrogen on Pt(111). ACS Catal. 4, 3307–3319 (2014).

Clayborne, A., Chun, H., Rankin, R. B. & Greeley, J. Elucidation of pathways for NO electroreduction on Pt(111) from first principles. Angew Chem Int Ed. 54, 8255–8258 (2015).

Liu, Z., Jenkins, S. J. & King, D. A. Step-Enhanced selectivity of NO reduction on platinum-group metals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 14660–14661 (2003).

Rima, F. R., Nakata, K., Shimazu, K. & Osawa, M. Surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopic studies of adsorbed nitrate, nitric Oxide and related compounds. 3. formation and reduction of adsorbed nitrite at a platinum electrode. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 6011–6018 (2010).

Burch, R., Daniells, S. T. & Hu, P. N2O and NO2 formation on Pt(111): A density functional theory study. J. Chem. Phys. 117, 2902 (2002).

Burch, R., Daniells, S. T. & Hu, P. The mechanism of N2O formation via the (NO)2 dimer: a density functional theory study. J. Chem. Phys. 121, 2737 (2004).

Duca, M., Cucarella, M. O., Rodriguez, P. & Koper, M. T. M. Direct reduction of nitrite to N2 on a Pt(100) electrode in alkaline media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 18042–18044 (2010).

Shin, H., Jung, S., Bae, S., Lee, W. & Kim, H. Nitrite reduction mechanism on a Pd surface. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 12768–12774 (2014).

Ahmed, F. et al. CO oxidation and NO reduction on a MgO(100) supported Pd cluster: A quantum chemical molecular dynamics study. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 24123–24132 (2011).

Huai, L. et al. NO dissociation and reduction by H2 on Pd(111): A first-principles study. J. Catal. 322, 73–83 (2015).

Beniya, A. et al. Adsorption and reaction of NO on the clean and nitrogen modified Rh(111) surfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 131, 084704 (2009).

Gonzalez, S., Loffreda, D., Sautet, P. & Illas, F. Theoretical study of NO dissociation on stepped Rh(221) and RhCu(221) surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 11376–11383 (2007).

Siriwatcharapiboon, W. et al. Promotion effects of Sn on the electrocatalytic reduction of nitrate at Rh nanoparticles. ChemElectroChem 1, 172–179 (2014).

Loffreda, D., Simon, D. & Sautet, P. Structure sensitivity for NO dissociation on palladium and rhodium surfaces. J. Catal. 213, 211–225 (2003).

Loffreda, D., Simon, D. & Sautet, P. Molecular and dissociative chemisorption of NO on palladium and rhodium (100) and (111) surfaces: A density-functional periodic study. J. Chem. Phys. 108, 6447 (1998).

Rempel, J. et al. Step effects on the dissociation of NO on close-packed rhodium surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 20623–20631 (2009).

Rosca, V. & Koper, M. T. M. Mechanism of electrocatalytic reduction of nitric oxide on Pt(100). J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 16750–16759 (2005).

He, C., Wang, H., Zhu, P. & Liu, J. Adsorption and dissociation of NO on Ir(100): a first-principles study. J. Chem. Phys. 135, 204707 (2011).

Ding, X. et al. Interaction of carbon dioxide with Ni(110): A combined experimental and theoretical study. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 76, 195425 (2007).

Mahata, A., Rai, R. K., Choudhuri, I., Singh, S. K. & Pathak, B. Direct vs. indirect pathway for nitrobenzene reduction reaction on a Ni catalyst surface: a density functional study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 26365–26374 (2014).

Zhang, J., Yang, H., Fang, J. & Zou, S. Synthesis and oxygen reduction activity of shape-controlled Pt3Ni nanopolyhedra. Nano Lett. 10, 638–644 (2010).

Zhang, C., Sandorf, W. & Peng, Z. Octahedral Pt2CuNi uniform alloy nanoparticle catalyst with high activity and promising stability for oxygen reduction reaction. ACS Catal. 5, 2296–2300 (2015).

Park, J. et al. Atomic layer-by-layer deposition of platinum on palladium octahedra for enhanced catalysts toward the oxygen reduction reaction. ACS Nano 9, 2635–2647 (2015).

Zhao, X. et al. Octahedral Pd@Pt1.8Ni core–shell nanocrystals with ultrathin PtNi alloy shells as active catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 2804–2807 (2015).

Choi, S. et al. Synthesis and characterization of Pd@Pt–Ni core–shell octahedra with high activity toward oxygen reduction. ACS Nano 8, 10363–10371 (2014).

Aminopirooz, S., Schmaltz, A., Becker, L. & Haase, J. Threefold-coordinated hollow adsorption site for c(4 × 2)-NO/Ni(111): A surface-extended x-ray-absorption fine-structure study. Phys. Rev. B 45, 6337 (1992).

Lindsay, R. et al. The structure of NO on Ni(111) at low coverage.Surf. Sci. 405, L566–L572 (1998).

Mapledoram, L. D., Wander, A. & King, D. A. Islanding or random growth? The low coverage growth modes and structure of NO on Ni{111} studied by diffuse ATLEED. Surf. Sci. 312, 54–61 (1994).

Caputi, L. S. et al. Orientational study of low coverage CO and NO on Ni(111). Surf. Sci. 289, L591–L594 (1993).

Wu, S. & Ho, J. The interaction of NOx on Ni(111) surface investigated with quantum-chemical calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 13707–13714 (2010).

Wu, S., Lin, Y. & Ho, J. Reaction of NO on Ni-Pt bimetallic surfaces investigated with theoretical calculations. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 7538–7544 (2011).

Chang, C. & Ho, J. Catalytic enhancement in dissociation of nitric oxide over rhodium and nickel small-size clusters: a DFT study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 5393–5398 (2014).

Brown, W. A. & King, D. A. NO chemisorption and reactions on metal surfaces: A new perspective. J. Phys. Chem. B 104, 2578–2595 (2000).

Tian, N., Zhou, Z., Sun, S., Ding, Y. & Wang, Z. L. Synthesis of tetrahexahedral platinum nanocrystals with high-index facets and high electro-oxidation activity. Science 316, 732–735(2007).

Tian, N., Zhou, Z. & Sun, S. Platinum metal catalysts of high-index surfaces: From single-crystal planes to electrochemically shape-controlled nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 112, 19801–19817 (2008).

Mahata, A., Choudhuri, I. & Pathak, B. A cuboctahedral platinum (Pt79) nanocluster enclosed by well defined facets favours di-sigma adsorption and improves the reaction kinetics for methanol fuel cells. Nanoscale 7, 13438–13451 (2015).

Piotrowski, M. J. & Piquini, P. Adsorption of NO on the Rh13, Pd13, Ir13 and Pt13 clusters: A density functional theory investigation. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 20540–20549 (2012).

Liu, X., Tian, D., Ren, S. & Meng, C. Structure sensitivity of NO adsorption–dissociation on Pdn (n = 8, 13, 19, 25) clusters. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 12941–12948 (2015).

Xu, Y., Getman, R. B., Sheltonc, W. A. & Schneider, W. F. A first-principles investigation of the effect of Pt cluster size on CO and NO oxidation intermediates and energetics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 6009–6018 (2008).

Xie, H., Ren, M., Lei, Q. & Fang, W. Nitric oxide adsorption and reduction reaction mechanism on the Rh7+ cluster: A density functional theory study. J. Phys. Chem. A 115, 14203–14208 (2011).

Dobrin, S. CO oxidation on Pt nanoclusters, size and coverage effects: a density functional theory study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 12122–12129 (2012).

Yudanov, I. V., Genest, A. & Rösch, N. DFT Studies of palladium model catalysts: structure and size effects. J. Cluster Sci. 22, 433–448 (2011).

Yudanov, I. V., Genest, A., Schauermann, S., Freund, H. J. & Rösch, N. Size dependence of the adsorption energy of CO on metal nanoparticles: A DFT search for the minimum value. Nano Lett. 12, 2134–2139 (2012).

Li, L. et al. Investigation of catalytic finite-size-effects of platinum metal clusters. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 222–226 (2013).

Lopez, N. et al. On the origin of the catalytic activity of gold nanoparticles for low-temperature CO oxidation. J. Catal. 223, 232–235 (2004).

Molina, L. M. & Hammer, B. Some recent theoretical advances in the understanding of the catalytic activity of Au. Appl. Catal. A 291, 21–31 (2005).

Helveg, S. et al. Atomic-scale imaging of carbon nanofibre growth. Nature 427, 426–429 (2004).

Mahyari, M. & Shaabani, A. Nickel nanoparticles immobilized on three-dimensional nitrogen-doped graphene as a superb catalyst for the generation of hydrogen from the hydrolysis of ammonia borane. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 16652–16659 (2014).

Geng, J., Jefferson, D. A. & Johnson, B. F. G. The unusual nanostructure of nickel–boron catalyst. Chem. Commun. 969–971 (2007).

Jiang, Z., Xie, J., Jiang, D., Wei, X. & Chen, M. Modifiers-assisted formation of nickel nanoparticles and their catalytic application to p-nitrophenol reduction. CrystEngComm 15, 560–569 (2013).

Chen, D. & Hsieh, C. Synthesis of nickel nanoparticles in aqueous cationic surfactant solutions. J. Mater. Chem. 12, 2412–2415 (2002).

Rosca, V., Beltramo, G. L. & Koper, M. T. M. Reduction of NO adlayers on Pt(110) and Pt(111) in acidic media: evidence for adsorption site-specific reduction. Langmuir 21, 1448–1456 (2005).

Cuesta, A. & Escudero, M. Electrochemical and FTIRS characterisation of NO adlayers on cyanide-modified Pt(111) electrodes: the mechanism of nitric oxideelectroreduction on Pt. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 3628– 3634 (2008).

Baker, R. A. & Doerr, R. C. Catalyzed nitric oxide reduction with carbon monoxide. Ind. Eng. Chem. Process Des. Dev. 4, 188–191 (1965).

Burch, R., Shestov, A. A. & Sullivan, J. A. A Transient Kinetic Study of the Mechanism of the NO+H2 Reaction over Pt/SiO2 Catalysts: 1. Isotopic Transient Kinetics and Temperature Programmed Analysis. J. Catal. 186, 353–361 (1999).

Stolbov, S. & Rahman, T. S. First-principles study of some factors controlling the rate of ammonia decomposition on Ni and Pd surfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 123, 204716 (2005).

Zeng, Z. H., Silva, J. L. F. D. & Li, W. X. Theory of nitride oxide adsorption on transition metal (111) surfaces: a first-principles investigation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 2459–2470 (2010).

Orita, H. & Itoh, N. Adsorption of N2 and N2O on Ni(755) surface: ab initio periodic density functional study. Sur. Sci. 550, 166–176 (2004).

Kodama, C., Orita, H. & Nozoye, H. Peculiar decomposition behavior of N2O on Ni(755). Appl. Surf. Sci. 121/122, 579–582 (1997).

Orita, H., Kondoh, H. & Nozoye, H. Decomposition of N2O on Ni(755) and the character of the atomic oxygen deposited at step sites. J. Catal. 177, 217–223 (1998).

Yoshinobu, J., Zenobi, R., Xu, J., Xu, Z. & Yates, J. T. Jr. N2 chemisorption on Ni(111). An infrared investigation under steady‐state conditions. J. Chem. Phys. 95, 9393 (1991).

Rai, R. K. et al. Room-temperature chemoselective reduction of nitro groups using non-noble metal nanocatalysts in water. Inorg. Chem. 53, 2904–2909 (2014).

Burch, R., Shestov, A. A. & Sullivan, J. A. A transient kinetic study of the mechanism of the NO+H2 reaction over Pt/SiO2 catalysts: 1. isotopic transient kinetics and temperature programmed analysis. J. Catal. 186, 353–361 (1999).

Zhou, S., Varughese, B., Eichhorn, B., Jackson, G. & McIlwrath, K. Pt–Cu core–shell and alloy nanoparticles for heterogeneous NOx reduction: Anomalous stability and reactivity of a core–shell nanostructure. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 4539–4543 (2005).

Bukoski, A., Abbott, H. L. & Harrisona, I. Microcanonical unimolecular rate theory at surfaces. III. Thermal dissociative chemisorption of methane on Pt(111) and detailed balance. J. Chem. Phys. 123, 094707 (2005).

Blochl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phy. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phy. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phy. Rev. B 49, 14251–14269 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phy. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Atoms, molecules, solids and surfaces: Applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation. Phy. Rev. B 46, 6671–6687 (1992).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical gga-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comp. Chem. 27, 1787–1799 (2006).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, S. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Henkelman, G. & Jonsson, H. Improved tangent estimate in the nudged elastic band method for finding minimum energy paths and saddle points. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9978–9985 (2000).

Acknowledgements

We thank IIT Indore for the lab and computing facilities. This work is supported by CSIR [Grant number: 01(2723)/13/EMR(II)] and DST-SERB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M. designed the project, did the calculation work and wrote the manuscript. K.S.R. and I.C. helped in the scientific discussion and commented on the manuscript. B.P. supervised the project and co-wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Mahata, A., Rawat, K., Choudhuri, I. et al. Octahedral Ni-nanocluster (Ni85) for Efficient and Selective Reduction of Nitric Oxide (NO) to Nitrogen (N2). Sci Rep 6, 25590 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25590

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25590

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.