Abstract

The interpenetrating morphology formed by the electron donor and acceptor materials is critical for the performance of polymer:fullerene bulk heterojunction (BHJ) photovoltaic (PV) cells. In this work we carried out a systematic investigation on a high PV efficiency (>6%) BHJ system consisting of a newly developed 5,6-difluorobenzo[c]1,2,5 thiadiazole-based copolymer, PFBT-T20TT and a fullerene derivative. Grazing incidence X-ray scattering measurements reveal the lower-ordered nature of the BHJ system as well as an intermixing morphology with intercalation of fullerene molecules between the PFBT-T20TT lamella. Steady-state and transient photo-induced absorption spectroscopy reveal ultrafast charge transfer (CT) at the PFBT-T20TT/fullerene interface, indicating that the CT process is no longer limited by exciton diffusion. Furthermore, we extracted the hole mobility based on the space limited current (SCLC) model and found that more efficient hole transport is achieved in the PFBT-T20TT:fullerene BHJ as compared to pure PFBT-T20TT, showing a different trend as compared to the previously reported highly crystalline polymer:fullerene blend with a similar intercalation manner. Our study correlates the fullerene intercalated polymer lamella morphology with device performance and provides a coherent model to interpret the high photovoltaic performance of some of the recently developed weakly-ordered BHJ systems based on conjugated polymers with branched side-chain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organic semiconductors offer opportunities for manufacturing low-cost, roll-to-roll compatible photovoltaic (PV) cells because of their low-temperature solution processibility1,2,3,4,5,6,7. To obtain high PV efficiency, it is desirable to create an interpenetrating network of electron- donor and acceptor components within the active layer, creating what is often referred to as a “bulk heterojunction” (BHJ)2. Organic BHJ PV cells based on blends of a conjugated polymer (donor) and a fullerene derivative (acceptor) have shown rapidly increasing efficiencies owing to the remarkable progress in material design and processing8,9,10,11. In these BHJ cells, the PV performance depends crucially on the nanoscale interpenetrating morphology. In detail, the domain size of each component, the nature of the hetero-interface and the configuration of molecular packing would all affect the photogeneration and extraction of charge carriers12,13,14.

Crystallinity, or ordering, of conjugated polymers is often correlated with exciton and charge transport properties15,16. In the past decades, many studies have been focused on BHJ systems formed by a proto-type semicrystalline polymer, poly (3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) and a fullerene derivative, phenyl-C61-butyric acid methyl ester (PC61BM)17,18,19. The studies correlate high PV performance with two-phase morphology that consists of pure polymer and pure fullerene domains with an optimal domain size comparable to the diffusion length of excitons10,11,20,21. Recently, alternative views of morphology have been proposed for other BHJ material systems22,23,24,25,26,27. For instance, an intermixing phase, called “a bimolecular crystal”, was observed in a BHJ of a long side-chain polymer, poly(2,5-bis(3-hexadecylthiophen-2-yl)thieno3,2-bthiophene (pBTTT) and phenyl-C71-butyric acid methyl ester (PC71BM)22,26. In this structure, the pBTTT and PC71BM molecules are arranged in a highly ordered fashion with PC71BM intercalated between the side chains of pBTTT25,27. Despite its high crystallinity, the pBTTT: PC71BM BHJ demonstrates a relatively low power conversion efficiency (PCE) of 2–3%28. On the other hand, an amorphous intermixing phase has been reported in a BHJ of thieno[3,4-b]thiophene/benzodithiophene (PTB7) and PC71BM8,9,29,30. The studies suggest that the BHJ is composed of pure PCBM droplet dispersed in an intermixed PTB7:PC71BM matrix. Shrinking the fullerene domain size (by using a solvent additive) can help to achieve a higher interface-to-volume ratio and consequently facilitate charge separation and achieve high PV efficiency (>8%)12,31. Another representative amorphous BHJ system with high PV performance is the blend of poly [N-9-hepta-decanyl-2,7-car-bazole-alt-5,5-(4,7-di-2-thienyl-2,1,3-benzothiadiazole)] (PCDTBT) and PC71BM31. Different from pBTTT and PTB7, pure PCDTBT films already show amorphous structure33. X-ray studies revealed an unusual bilayer lamellar structure in both pure PCDTBT and PCDTBT:PC71BM blend. This bilayer structural motif likely contributes to this material's superior PV performance34.

In this work we focused on an amorphous-like BHJ system consisting of a newly developed donor-acceptor copolymer, PFBT-T20TT and PC71BM, which yields a PCE of over 6% in a PV structure. Grazing incidence X-ray scattering (GIXS) measurements show the intercalation of PC71BM molecules between the PFBT-T20TT lamella in an intermixed domain. Different from the pBTTT:PC71BM system, the isotropic nature of PFBT-T20TT network leads to formation of more effective percolation paths for charge transport and thus allows lower loading ratio of fullerene to achieve optimized PV performance. Steady-state and transient photo-induced absorption spectroscopy reveals ultrafast charge transfer (CT) at the PFBT-T20TT/PC71BM interface, indicating that the CT process is no longer limited by exciton diffusion. Furthermore, space charge limited current (SCLC) model is used to extract the hole mobility for pure PFBT-T20TT and PFBT-T20TT: PC71BM BHJ. The result suggests that more efficient hole transport is achieved in the PFBT-T20TT:PC71BM BHJ as compared to pure PFBT-T20TT.

Results and Discussions

PV Characteristics

Figure 1 shows the device information for the PFBT-T20TT:PC71BM (1:2 mass ratio) BHJ PV cells based on a structure of ITO/PEDOT:PSS/PFBT-T20TT:PC71BM/Ca/Al. The current density-voltage (J–V) characteristics of the PV cell are plotted in Figure 1(a), which exhibit an open-circuit voltage (Voc) of 0.82 V, an short-circuit current density (Jsc) of 12.93 mA·cm−2, a fill factor of 61% and an overall PCE of 6.3% under AM 1.5 illumination. Figure 1(b) represents the detailed energy level alignments of the PV cells. The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy levels of PFBT-T20TT are −5.46 eV and −3.59 eV, respectively. For optimized PFBT-T20TT:PCBM mixing ratio (1:2), all devices show efficiency over 5% (Figure S1, Supplementary Information). Adding more PC71BM loading would lead to lower Jsc and fill factor, thus reducing the PCE (Figure S1, Supplementary Information).

Morphology and Structure

To investigate the morphology and molecular packing in pure PFBT-T20TT and PFBT-T20TT: PC71BM blends, we carried out grazing-incidence wide-angle X-ray scattering (GIWAXS) (Figure 2(a–c)) measurements. The GIWAXS pattern of pure PFBT-T20TT thin film (Figure 2(a)) exhibits an intense peak along qz axis at q = 0.25 Å−1, indicating a preferential lamellar stacking in the surface normal direction with a lattice spacing of 25.13 Å. This so-called “edge-on” lamellar stacking was commonly observed in pure P3HT thin films35. However, in contrast to P3HT:PCBM blends, this lamellar ordering was not preserved in PFBT-T20TT:PC71BM blend thin films in mass ratios of 1:2 and 1:4, indicated by the disappearance of the lamellar peak in the corresponding GIWAXS patterns (Figure 2(b,c)). Only the amorphous PC71BM ring at q ≈ 1.3 Å−1 and monotonically decreasing scattering intensity from the origin were observed in Figure 2(b,c). The PC71BM ring is narrower in Figure 2(c), which is reasonable as the higher loading of PC71BM may lead to a bit better ordering in the amorphous PC71BM domains. Just from the GIWAXS patterns, we cannot tell whether the mixing of PFBT-T20TT and PC71BM gives rise to a randomly mixed molecular packing structure without lamellar ordering or the lamellar structure is still maintained while its corresponding peak moves to a smaller q region which was shadowed by the beam stop of the GIWAXS detector.

2D GIWAXS patterns of (a) pure PFBT-T20TT film (b) 1:2 and (c) 1:4 PFBT-T20TT: PC71BM blend films and (d-f) the corresponding 2D GISAXS patterns. (g–h) Intensity integrals versus |q| of (g) GIWAXS and (h) GISAXS patterns for pure PFBT-T20TT and PFBT-T20TT:PC71BM blends in the mass ratio of 1:2 and 1:4. The integrals are taken over a polar range between 30° and 45°, as illustrated in (d).

Herein, grazing incident small-angle X-ray scattering (GISAXS) measurements were performed simultaneously to complement the scattering in the smaller q region that is uncovered in GIWAXS19,35,36,37,38. Figure 2(d–f) present the GISAXS results for pure PFBT-T20TT, 1:2 and 1:4 PFBT-T20TT: PC71BM blend thin films, respectively. The vertical streak along qz axis originates from the intense diffuse reflectivity, which is partially blocked by the beam stop. The horizontal streak at q ~ 0.03 Å−1 is the so called “Yoneda” peak due to the scattering enhancement at the critical angle of the sample39. Besides these signatures of GISAXS, additional scattering features resulting from the molecular packing of the films were observed. In Figure 2(d), the pure thin film exhibits a broad peak at the upper right corner of the scattering pattern (as indicated by the arrow). In Figure 2(e, f), this broad peak disappears while another broad arc appears at smaller q. This corresponds to an enlargement of certain layer spacing.

In order to figure out a detailed molecular packing scheme for PFBT-T20TT before and after the mixing with PC71BM, intensity integrals along the radial axis over a polar range between 30° and 45° was plotted for all the GIWAXS (Figure 2 (g)) and GISAXS patterns (Figure 2 (h)). In the GIWAXS integrals (shown in Figure 2(g)), the peaks at q ≈ 1.3 Å−1 come from the amorphous PC71BM domains in the PFBT-T20TT: PC71BM BHJ blends. For the pure PFBT-T20TT sample (blue curve), a lamellar peak locating at q = 0.25 Å−1, can be clearly identified. No lamellar peaks were observed for the blends. (Note that the cutoff of the beamstop locates at q ~ 0.2 Å−1.) We now turn to the GISAXS integrals (Figure 2(h)) where smaller q values corresponding to larger length scale can be resolved. First, in the overlapping q region of GIWAXS and GISAXS we observed consistently the lamellar peak at q = 0.25 Å−1 for pure polymer. Interestingly, this peak moves to a new position at q = 0.166 Å−1 for the blends (Figure 2(h)), corresponding to an increasing of lamellar spacing from 25.1 Å to 37.8 Å. The 12 Å increase in the lamellar spacing indicates intercalation of PC71BM molecules between the PFBT-T20TT lamellar after the mixing. Similar behavior was reported for the pBTTT system, where about 9 Å lamellar spacing increase is found after mixing with fullerenes40. The lamellar peak of the blends are much broader and weaker than that of the pure polymer, confirming the weakly-ordered morphology of this BHJ system.

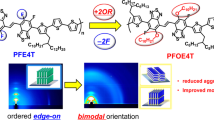

Figure 3 illustrates the schematics of the molecular packing for pure PFBT-T20TT and blends based on the combined GIWAXS and GISAXS results. Despite the lack of strong π-π stacking (Figure S2, Supplementary Information), lamellar stacking is preferentially normal to the substrate in pure PFBT-T20TT thin films as illustrated in Figure 3(a). Blend films are more disordered with no preferential lamellar orientation (Figure S3, Supplementary Information), as evidenced by the ring-like lamellar peak observed in the scattering patterns. The significant shift in the lamellar spacing strongly suggests the intercalation of fullerene derivatives into the PFBT-T20TT domains (Figure 3 (b)). It is likely that the branched side chains attached to PFBT-T20TT backbones provide ample room for the PC71BM molecules. No crystalline PFBT-T20TT domain remains after mixing, as indicated by the scattering data. Note that when increasing the polymer:PCBM ratio from 1:2 to 1:4 the lamella distance of the polymer stays the same, indicating that a constant PCBM fraction in the mixing phase.

Exciton Dissociation and Charge Separation

Correlating the charge-separation mechanism and nanoscale molecular packing of the organic BHJ solar cells could facilitate optimization of their overall efficiency41,42,43. In order to understand how the intercalation of PC71BM between the PFBT-T20TT backbones affects the charge generation process, we performed ultrafast transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy measurements. Figure 4 (a) shows the TA spectra of a pure PFBT-T20TT film upon excitation at 600 nm. A broader and positive fractional transmission signal (ΔT/T) is found from 530 nm to 800 nm and is mainly attributed to photobleaching (PB) and stimulated emission (SE) with probably some overlap with a stimulated emission band at longer wavelengths. A red shift of the band can be noticed in the first ten ps which may be related to exciton diffusion to lower energy states (see dynamics in the Figure S4, Supplementary Information). Also two negative bands appear upon photoexcitation at wavelengths, λ < 530 nm (PA1) and λ > 800 nm (PA2). The latter, though broad, is centering around 1050 nm. All bands exhibit virtually the same decay dynamics (Figure S4, Supplementary Information) thus suggesting that they are all related to the transitions from the first excited singlet state.

The TA spectra of the PFBT-T20TT: PC71BM blend are shown in Figure 4 (b). In this, photoexcited state dynamics are modified by the interface effect. Firstly, no shift can be observed towards longer wavelength of the broad positive band. This may indicate both an quenching of the SE signal band and a lack diffusive dynamics, in both cases pointing to effective charge transfer at the PFBT-T20TT:PC71BM interface. The negative bands in the near-infrared (NIR) region change its features. The broad band centered at 1050 nm for the pure film is now shifted for the blends and splitted in a main band (PA*1) peaking around ~1100 nm; and a second one, which can be as a tail of a negative band peaking around 800 nm. In the inset a zoom of the spectrum at 400ps time delay is presented. Note that the spectral shape perfectly matches with the steady-state photo-induced absorption measurement (Figure S4, Supplementary Information), thus leading us to conclude that the two PA bands, not present in the pure film, represent the fingerprint of charges (i.e., polaron) in PFBT-T20TT. Importantly, the PA* bands appear from the earliest time (<200 fs) and get further resolved over time (probably due to an initial overlap with the singlet PA2 band). This suggests that due to PC71BM intercalation, the fine intermixing results in the ultrafast charge formation in PFBT-T20TT (<150 fs). To further confirm our hypothesis, we investigated the BHJ of another PFBT derivative, PFBT-T12TT and with the same mass ratio. In PFBT-T12TT, the PFBT backbone remains the same while the side chain is shortened. No PC71BM intercalation was observed in this system (Figure S5, Supplementary Information). The TA spectra of PFBT-T12TT: PC71BM blend shows a clear difference in the NIR negative band as compared to the PFBT-T20TT: PC71BM blend, with the PA* band charge bands growing after the 1 ps (Figure S5, Supplementary Information), suggesting that the charge transfer without fullerene intercalation is not ultrafast, but still limited by exciton diffusion from pure PFBT-T12TT phase to the PFBT-T12TT/PC71BM interface. It is worth noting that despite the ultrafast charge transfer (<150 fs), biomolecular recombination in PFBT-T20TT:PC71BM still follows the same dynamics (Figure S4, Supplementary Information) as PFBT-T12TT:PC71BM and other BHJ systems. This suggests that charge generation yield is not compromised due to the intercalation of PC71BM.

Hole transport studies on PFBT-T20TT: PC71BM BHJ systems

Thin-film transistor (TFT) and space charge-limited current (SCLC) measurements were used to investigate the in-plane and out-of-plane film mobilities respectively. Pure PFBT-T20TT exhibits an optimized hole mobility (μ) of 1.02 × 10−2 cm2·(V·s)−1 in field-effect transistor (FET) configurations (Figure S1, Supplementary Information). Intermixing fullerene molecules with polymer can either increase or decrease the hole mobility of the polymer by several orders of magnitude17,44. It has been observed in P3HT: PCBM blends that intimate mixing of P3HT and PCBM disrupts P3HT crystallization45,46, resulting in a decrease of hole mobility17. In contrast, hole mobility of PCDTBT and poly(2-methoxy-5-{3′,7′-dimethyloctyloxy}-p-phenylene vinylene) (MDMO-PPV) films are increased when fullerene derivatives are added47. To gain insights into how PC71BM intercalation affect the hole transport in PFBT-T20TT, we fabricated hole-only diodes based on both pure PFBT-T20TT and PFBT-T20TT: PC71BM BHJ. In our hole-only diodes we used MoO3/Pd (~5.3 eV) as the electron blocking contact and PEDOT: PSS (~5.0 eV) as the hole injection contact. A thin layer of MoO3 can prevent Pd diffusion into the organic layer during evaporation. Both contacts can provide large barriers for electron injection and ensure efficient hole injection. Figure 5 shows the JV characteristics of the devices, together with the fitting curves generated from the space charge limited model17,44,47. The fitting results shown in Table 1 clearly suggest that the hole mobility increases in the blend. This can be understood by the cartoon presented in Figure 3. For the diode configuration the direction of hole transport is perpendicular to the substrates. In the pure PFBT-T20TT device the polymer backbones mostly take the edge-on orientation and the hole transport is limited by hopping between the largely separated lamella of backbones. On the other hand, when blended with PC71BM, the orientation of PFBT-T20TT becomes randomly oriented. This morphology helps formation of more efficient percolation pathways for holes, thus resulting in enhanced hole mobility. Note here the hole mobility of 1:4 blend is improved from that of the pure polymer film, but not as high as the 1:2 blend. This is reasonable since more PC71BM loading leads to improved ordering in the amorphous PC71BM domains, which will impede the hold transport to some extent. To obtain a complete picture of the charge transport process, we also fabricated and characterized electron-only devices for pure PC71BM and PFBT-T20TT:PC71BM blends (Figure S6, Supplementary Information). The results show that although the electron mobility is reduced from 2.34 × 10−3 cm2·(V·s)−1 for pure to 1.05 × 10−3 cm2 (V·s)−1 for the 1:2 blend, the electron and hole mobility is on the same order and therefore the transport can be well balanced in the 1:2 blended PV cells.

Conclusions

In summary, we investigated the impact of molecular packing on the electronic processes in PFBTT20TT:PC71BM BHJ system, which exhibits a low degree of crystallinity while yields relatively high PCE in solar cell structures. The GIXS measurement reveals an intermixing morphology with intercalation of fullerene molecules between the PFBT-T20TT lamella. To understand how this morphology affects the electronic processes in the PV cells, we performed spectroscopic measurements on the BHJ system to probe the charge transfer (CT) process. Steady-state and transient photo-induced absorption spectroscopy reveal ultrafast CT at the polymer/fullerene interface, indicating that the CT process is no longer limited by exciton diffusion. This is very different from the prototype P3HT:fullerene BHJ PV cells. Also, we studied the charge transport property and found that more efficient hole transport is achieved in the BHJ as compared to pure polymer, exhibiting a different trend as compared to the previously reported highly crystalline polymer:fullerene blend that shows a similar intercalation behavior. These, together with the ultrafast charge photo-generation process, are critical to achieve highly efficient BHJ solar cells. How morphology and miscibility of donor and acceptor materials affect the PV performance has been a key question to answer for this research field. Our study sheds new light on this question and provides a coherent model to interpret the high PV performance of some of the recently developed weakly-ordered BHJ systems based on conjugated polymers with branched side-chain.

Methods

Device Fabrication

ITO-coated glass substrates were cleaned stepwise in detergent, water, acetone and isopropyl alcohol under ultrasonication for 10 min each and subsequently dried by N2 blowing and then pretreated by the oxygen plasma for 1.5 min. The PEDOT:PSS (VP Al 4083 FROM H.C.Stack, filtered through 0.45 μm PVDF syringe filter) buffer layer was spin-coated at 3000 rpm for 60 s. Then, the ITO substrates with PEDOT:PSS layer were annealed at 155°C for 10 minutes in a nitrogen-filled glove box (<0.1 ppm O2 and H2O). After that, the active layer was spin-coated from the PFBT-T20TT:PC71BM dichlorobenzene solution at 1000 rpm for 60 s, followed by thermal annealing at 155°C for 10 minutes. Ca and Al were subsequently thermal evaporated as the top contacts through a shadow mask. It is noted that the defined active area of devices is 2 × 1.5 mm2. FETs with double-gate, bottom-contact configuration were fabricated on a heavily n-type-doped silicon wafer with a SiO2 layer. The Au contacts were treated with a 10 mM solution of pentafluorobenzene thiol in isopropyl alcohol for 2 min. Then, the 4 mg/mL PFBT-T20TT solution in dichlorobenzene was spin-cast at 2000 rpm. The active layer deposition was carried out in a N2 atmosphere controlled glovebox and followed by annealing at 155°C for 10 minutes. After that, the gate electrode Al was deposited by thermal evaporation. The fabrication of the hole only diodes and the electron only diodes kept the same processes as solar cells but with different interfacial layers. For electron only diode, the processing of ZnO followed the method described by S. Bai et al49. The SCLC mobilities were estimated using the Mott-Gurney square law17,44,47,48.

Device Characterizations

JV Characteristics of the solar cells were measured by a Keithley 236 source meter unit. The light source was calibrated by using silicon reference cells with an AM 1.5 G solar simulator with an intensity of 1000 W m−2. Characterizations of FETs were carried out by a Keithley 2612 analyzer. The morphologies of pristine PFBT-T20TT film and PFBT-T20TT:PC71BM BHJ film were investigated by AFM (DI, Nanoscope III). The films were spin-cast on silicon wafer and annealed at 155°C for 10 min for AFM measurements. For selected area electron diffraction (SAED), the films were prepared by first spin coating a 4 mg/ml Dichlorobenzene solution onto mica substrates. The substrates were then dissolved in aqueous hydrogen fluoride and the resulting organic layer was transferred to a copper mesh TEM grid. SAED images were taken on a FEI Tecnai G2 F20 electron microscope with an accelerating voltage of 160 kV.

X-ray scattering measurements

The GIXS experiments were performed at the 23A SWAXS beamline of a superconductor wiggler at the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center, Hsinchu50. With a 10.0 keV (λ = 1.3776 nm) beam of 0.15 mm in height and 0.2 mm in width, GISAXS and GIWAXS data were collected together at 0.15o beam incidence, using respectively Pilatus 1M-F and C9728DK area detectors.The scattering image presents out-of-plane structure (normal to the substrate) along vertical axis (qz) and in-plane structure (parallel to the substrate) along horizontal axis (qr). We have accounted for the intersection of Ewald sphere and reciprocal space in the extracted scattering profiles and the measured peak positions.

CW Photoinduced Absorption

Photoinduced absorption (PIA) spectroscopy is a quasi-cw pump-probe technique sensitive to the absorption of photo-generated long-lived species (from μs to ms). A mechanical chopper modulated light beam (a diode laser at 532 nm) excites samples. Using a “probe-light” (a 100 W halogen lamp) the excited species are analyzed. The changes in transmission under the photoexcitation were detected by a Germanium photodiode and a lock-in amplifier referenced to the modulation frequency, allowing a precise quantification of the signal in phase and out of phase respect to the laser pump. Finally, the signal was normalized to the unmodulated transmission for every wavelength (ΔT/T). All samples were measured in a cryostat at 80 K.

Ultra-fast transient absorption

In a typical pump-probe experiment, the system under study is resonantly photoexcited by a short “pump” pulse and its subsequent dynamical evolution is detected by measuring the transmission (T) changes of a delayed “probe” pulse as a function of pump-probe delay given by the differential transmission ΔT/T = [(Tpumpon − Tpumpoff)/Tpumpoff]. The laser source consists of a regene-ratively amplified mode-locked Ti:sapphire laser (Clark-MXR Model CPA-1), delivering pulses at 1 kHz repetition rate with 780 nm center wavelength, 150 fs duration (The limited time resolution measured from pump-probe cross correlation is 150 fs). A fraction of this beam is used to pump an optical parametric amplifier (OPA) capable of delivering tunable pulses in the visible (500-700 nm) with ≈10 nm bandwidth and 70–100 fs duration. Details can be found elsewhere51. Another small fraction of the Ti: sapphire amplified output is independently focused into a 1-mm-thick sapphire plate to generate a stable single-filament white-light supercontinuum, which serves as a probe pulse. A short-pass filter with 760 nm cutoff wavelength is used to filter out the residual 780 nm pump light. All samples were excited at 600 nm (10 nJ energy, 150 μm spot size) and measured in a vacuum chamber to prevent any oxygen effect or sample degradation.

References

Tang, C. W. Two–layer organic photovoltaic cell. App. Phys. Lett. 48, 183–185 (1986).

Yu, G., Gao, J., Hummelen, C. J., Wudl, F. & Heeger, A. J. Polymer Photovoltaic Cells: Enhanced Efficiencies via a Network of Internal Donor-Acceptor Heterojunctions. Science 270, 1789–1791 (1995).

Forrest, S. R. The path to ubiquitous and low-cost organic electronic appliances on plastic. Nature 428, 911–918 (2004).

Service, R. F. Outlook Brightens for Plastic Solar Cells. Science 332, 293 (2011).

Søndergaard, R. et al. Roll to roll fabrication of polymer solar cells. Material today 15, 36–49 (2012).

You, J. et al. A polymer tandem solar cell with 10.6% power conversion efficiency. Nat. Commun. 4, 1446; 10.1038/ncomms2411 (2013).

Darling, S. B. & You, F. The case for organic photovoltaics. RSC Adv. 3, 17633-17648. (2013).

Chen, W. et al. Hierarchical nanomorphologies promote exciton dissociation in polymer/fullerene bulk heterojunction solar cells. Nano Lett. 11, 3707–3713 (2011).

Liang, Y. et al. For the Bright Future-Bulk Heterojunction Polymer Solar Cells with Power Conversion Efficiency of 7.4%. Adv. Mater. 22, 135–138 (2010).

Dou, L. et al. Tandem polymer solar cells featuring a spectrally matched low-bandgap polymer. Nat. Photon. 6, 180–185 (2012).

He, Z. et al. Enhanced power-conversion efficiency in polymer solar cells using an inverted device structure. Nat. Photon. 6, 591–595 (2012).

Hammond, M. R. et al. Molecular Order in High-Efficiency Polymer/Fullerene Bulk Heterojunction Solar Cells. ACS Nano 5, 8248–8257 (2011).

Ma, W. et al. Domain Purity, Miscibility and Molecular Orientation at Donor/Acceptor Interfaces in High Performance Organic Solar Cells: Paths to Further Improvement. Adv. Energy Mater. 3, 864–872 (2013).

Chen, W., Nikiforov, M. P. & Darling, S. B. Morphology characterization in organic and hybrid solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 8045–8074 (2012).

Li, G. et al. Solvent annealing effect in polymer solar cells based on poly (3-hexylthiophene) and methanofullerenes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 17, 1636–1644 (2007).

Erb, T. et al. Correlation between structural and optical properties of composite polymerfullerene films for organic solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 15, 1193–1196 (2005).

Mihailetchi, V. D., Xie, H. X., de Boer, B., Koster, L. J. A. & Blom, P. W. M. Charge transport and photocurrent generation in poly(3-hexylthiophene):methanofullerene bulk-heterojunction solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 16, 699–708 (2006).

Kim, Y. et al. A strong regioregularity effect in self-organizing conjugated polymer films and high-efficiency polythiophene:fullerene solar cells, Nat. Mater. 5, 197–203 (2006).

Wu, W. R. et al. Competition between fullerene aggregation and poly(3-hexylthiophene) crystallization upon annealing of bulk heterojunction solar cells. ACS Nano 5, 6233–6243 (2011).

Benanti, T. L. & Venkataraman, D. Organic solar cells: an overview focusing on active layer morphology. Photosynth. Res. 87, 73–81 (2006).

Moon, J. S., Lee, J. K., Cho, S. N., Byun, J. Y., Heeger, A. J. ‘Columnlike’ structure of the cross-sectional morphology of bulk heterojunction materials. Nano Lett. 9, 230–234 (2009).

Mayer, A. C. et al. Bimolecular crystals of fullerenes in conjugated polymers and the implications of molecular mixing for solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 19, 1173–1179 (2009).

Yin, W. & Dadmun, M. A new model for the morphology of P3HT/PCBM organic photovoltaics from small-angle neutron scattering: rivers and streams. ACS Nano 5, 4756–4768 (2011).

Chen, D., Nakahara, A., Wei, D., Nordlund, D. & Russell, T. P. P3HT/PCBM bulk heterojunction organic photovoltaics: correlating efficiency and morphology. Nano Lett. 11, 561–567 (2011).

Beiley, Z. M. et al. Morphology-dependent trap formation in high performance polymer bulk heterojunction Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 1, 954–962 (2011).

Miller, N. C. et al. Factors governing intercalation of fullerenes and other small molecules between the side chains of semiconducting polymers used in solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2, 1208–1217 (2012).

Miller, N. C. et al. Use of X-Ray Diffraction, molecular simulations and spectroscopy to determine the molecular packing in a polymer-fullerene bimolecular crystal. Adv. Mater. 24, 6071–6079 (2012).

Parmer, J. E. et al. Organic bulk heterojunction solar cells using poly(2,5-bis(3- tetradecyllthiophen-2-yl)thieno[3,2,-b]thiophene). Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 113309 (2008).

Liang, Y. et al. Highly efficient solar cell polymers developed via fine-tuning of structural and electronic properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 7792–7799 (2009).

He, Z. et al. Simultaneous enhancement of open-circuit voltage, short-circuit current density and fill factor in polymer solar cells. Adv. Mater. 23, 4636–4643 (2011).

Collins, B. A. et al. Absolute measurement of domain composition and nanoscale size distribution explains performance in PTB7: PC71BM solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 3, 65–74 (2013).

Blouin, N., Michaud, A. & Leclerc, M. A low-bandgap poly(2,7-carbazole) derivative for use in high-performance solar cells. Adv. Mater. 19, 2295–2300 (2007).

Blouin, N. et al. Toward a Rational Design of Poly(2,7-Carbazole) Derivatives for Solar Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 732–742 (2008).

Lu, X. et al. Bilayer order in a polycarbazole-conjugated polymer. Nat. Commun. 3, 795; 10.1038/ncomms1790 (2012).

Hlaing, H. et al. Nanoimprint-induced molecular orientation in semiconducting polymer nanostructures. ACS Nano 5, 7532–7538 (2011).

Kozub, D. R. et al. Polymer crystallization of partially miscible polythiophene/fullerene mixtures controls morphology. Macromolecules 44, 5722–5726 (2011).

Szarko, J. M. et al. When function follows form: effects of donor copolymer side chains on film morphology and BHJ solar cell performance. Adv. Mater. 22, 5468–5472 (2010).

Liao, H. C. et al. Quantitative Nanoorganized structural evolution for a high efficiency bulk heterojunction polymer solar cell. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 13064–13073 (2011).

Yoneda, Y. Anomalous surface reflection of X rays. Physical Review 131, 2010–2013 (1963).

Mayer, A. C. et al. Bimolecular crystals of fullerenes in conjugated polymers and the implications of molecular mixing for solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 19, 1173–1179 (2009).

Gélinas, S. et al. Ultrafast long-range charge separation in organic semiconductor photovoltaic diodes. Science 343, 512–516 (2014).

Grancini, G. et al. Hot exciton dissociation in polymer solar cells. Nat. Mater. 12, 29–33 (2013).

Vandewal, K. et al. Efficient charge generation by relaxed charge-transfer states at organic interfaces. Nat. Mater. 13, 63–68 (2014).

Melzer, C., Koop, E. J., Mihailetchi, V. D. & Blom, P. W. M. Hole transport in poly(phenylene vinylene)/methanofullerene bulk-heterojunction solar cells. Adv. Funct. ?Mater. 14, 865–870 (2004).

Verploegen, E. et al. Effects of thermal annealing upon the morphology of polymer–fullerene blends. Adv. Funct. Mater. 20, 3519–3529 (2010).

Yang, X. et al. Nanoscale morphology of high-performance polymer solar cells. Nano Lett. 5, 579–583 (2005).

Blom, P. W. M., Mihailetchi, V. D., Koster, L. J. A. & Markov, D. E. Device physics of polymer:fullerene bulk heterojunction solar cells. Adv. Mater. 19, 1551–1566 (2007).

Mihailetchi, V. D., Blom, P. W. M., Hummleen, J. C. & Rispens, M. T. Cathode dependence of the open-circuit voltage of polymer:fullerene bulk heterojunction solar cells. J. Appl. Phys. 94, 6849 (2003).

Bai, S. et al. Inverted organic solar cells based on aqueous processed ZnO interlayers at low temporature. App. Phys. Lett. 100, 203906 (2012).

Jeng, U. et al. A small/wide-angle X-ray scattering instrument for structural characterization of air–liquid interfaces, thin films and bulk specimens. J. Appl. Cryst. 43, 110–121 (2010).

Cerullo, G. & Silvestri, S. D. Ultrafast optical parametric amplifiers. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 74, 1 (2003).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Yizheng Jin and Mr. Sai Bai from Zhejiang University for providing the ZnO precursor solution for the fabrication of the electron-only diodes. We gratefully acknowledge funding from Research Grant Council of Hong Kong (Grant No. CUHK 419311), Shun Hing Institute of Advanced Engineering (Grant no. 8115041), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 61205036) and CUHK Focused Innovation Scheme B Grant “Centre for Solar Energy Research” (Grant No. 1902034). J.Q.M. and X.L. acknowledge the financial support from CUHK Direct Grant No. 4053015. Y.W., X.X., Y.L., N.S.C., H.X. and B.S.O. also acknowledge the financial support from A*Star of Singapore for the project Grant No. 1021700135.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.X., X.H.L. and N.Z. wrote the main text. T.X. contributed to device and film fabrications, device characterizations and photo-induced absorption (PIA) spectroscopy measurements (Fig. 1, Fig. 5, Fig. S1, Fig. S2, Fig. S4 and Fig. S6). H.H.X. assisted in device characterizations and PIA spectroscopy measurements (Fig. S1 and Fig. S4). T.X., J.Q.M., U.S.J. and X.H.L. undertook the Grazing incidence X-ray scattering measurements and the interpretation of the morphology analysis (Fig. 2, Fig. S3 and Fig. S5). G.G. and A.P. were responsible for the transient spectroscopy measurements (Fig. 4, Fig. S4 and Fig. S5). Y.W., X.X., Y.L., N.S.C., H.X., B.S.O. conducted material design and synthesis. All authors agree the contents of the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supporting information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The images in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the image credit; if the image is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the image. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, T., Xu, H., Grancini, G. et al. Molecular Packing and Electronic Processes in Amorphous-like Polymer Bulk Heterojunction Solar Cells with Fullerene Intercalation. Sci Rep 4, 5211 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05211

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05211

This article is cited by

-

Influence of an Amide-Functionalized Monomeric Unit on the Morphology and Electronic Properties of Non-Fullerene Polymer Solar Cells

International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing-Green Technology (2022)

-

Improving the Power Conversion Efficiency and Stability of Planar Perovskite Solar Cells via Small Molecule Doping

Journal of Electronic Materials (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.