Abstract

Understanding magnetism and electron correlation in many unconventional superconductors is essential to explore mechanism of superconductivity. In this work, we perform a systematic numerical study of the magnetic and pair binding properties in recently discovered polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) superconductors including alkali-metal-doped picene, coronene, phenanthrene and dibenzopentacene. The π-electrons on the carbon atoms of a single molecule are modelled by the one-orbital Hubbard model and the energy difference  between carbon atoms with and without hydrogen bonds is taking into account. We demonstrate that the spin polarized ground state is realized for charged molecules in the physical parameter regions, which provides a reasonable explanation of local spins observed in PAHs. In alkali-metal-doped dibenzopentacene, our results show that electron correlation may produce an effective attraction between electrons for the charged molecule with one or three added electrons.

between carbon atoms with and without hydrogen bonds is taking into account. We demonstrate that the spin polarized ground state is realized for charged molecules in the physical parameter regions, which provides a reasonable explanation of local spins observed in PAHs. In alkali-metal-doped dibenzopentacene, our results show that electron correlation may produce an effective attraction between electrons for the charged molecule with one or three added electrons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The recent discovery of superconductivity in the solid state of various alkali-metal-doped PAHs, including picene1, coronene2, phenanthrene3,4 and 1, 2 : 8, 9-dibenzopentacene5, has attracted a growing interest in the condensed matter physics community. One of the most intriguing properties is that the superconducting transition temperature Tc increases dramatically with increasing the number of benzene rings, reaching up to 33.1 K as reported in alkali-metal-doped 1, 2 : 8, 9-dibenzopentacene5, comparable to that of alkali-metal-doped C606,7,8. This behavior suggests that PAHs with longer chains of benzene rings may exhibit higher Tc. Another interesting experimental finding is that the magnetic susceptibility in the normal state of superconducting compounds is considerable large and shows the Curie-Weiss behavior as a function of temperature1,3, evidencing that there exist local spins in the charge doped systems. Currently, the physical origin of local spins is unclear.

Theoretical studies mainly based on the first-principle calculations have been carried out to elucidate the superconducting mechanism in these PAH superconductors. There are three important findings: (1)The conduction band group around the Fermi level comprises four bands, which are derived from the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) and LUMO+19,10,11. (2) The bandwidth W around the Fermi energy is smaller than the effective Coulomb interaction Ueff in alkali-doped picene, placing it in the strong correlation regime12,13. (3) Intramolecular14,15, intermolecular and intercalant16 phonons are shown to have significant contribution to the electron-phonon interaction in alkali-doped picene. However, Kato et al.17 found that the electron-phonon coupling constant decreases with an increase of the number of carbon atoms in phenanthrene edge-type hydrocarbons, leading to a decrease of Tc with increasing size of phenanthrene edge-type hydrocarbons. This contradicts to the experimental results that Tc increases from ~ 5K in phenanthrene to ~ 33K in 1, 2 : 8, 9-dibenzopentacene. Finding (3) indicates that the superconductivity in PAHs can not be explained by considering only the electron-phonon interaction. Finding (2) suggests that electronic correlations are required to be taken into account for a complete understanding of the physical properties of PAHs.

To gain some insights on the effect of electronic correlations on the magnetic and pair binding properties of PAHs, we undertake a first step to study the electronic states on a single molecule, which provides an energy scale intermediate between the microscopic energetics at the level of carbon atom and the macroscopic scale of the molecular solids. The resulting many-body states form a basis for analyzing the low-energy physics at the length scale larger than the size of molecule18. The carbon atoms in PAHs are in a trigonal planar sp2 hybridization configuration with a half-filled pπ orbital perpendicular to the planar structure, which forms energy levels (including LUMO and LUMO+1) around the Fermi energy. The minimal description of interacting pπ-electrons on a single molecule is given by the one-orbital Hubbard model which incorporates an on-site Coulomb repulsion besides a simple Huckel picture for the one-electron part. The Hamiltonian reads,

The operators  and ciσ create and destroy a π-electron with spin σ at the ith carbon atom of a single molecule, respectively.

and ciσ create and destroy a π-electron with spin σ at the ith carbon atom of a single molecule, respectively.  is the number operator for an electron with spin σ at site i and ni = ni↑+ni↓. The sum 〈ij〉 is over nearest-neighbor (NN) carbon atoms and the primed sum runs over the carbon sites without connecting to hydrogen atoms. Here, U denotes the on-site Coulomb interaction and

is the number operator for an electron with spin σ at site i and ni = ni↑+ni↓. The sum 〈ij〉 is over nearest-neighbor (NN) carbon atoms and the primed sum runs over the carbon sites without connecting to hydrogen atoms. Here, U denotes the on-site Coulomb interaction and  the energy difference between carbon atoms with and without hydrogen bonds, which is due to different electron-negativity of carbon and hydrogen. Notice that the on-site Hubbard U is different from the effective Coulomb interaction Ueff12,13, which stands for the energetic cost to doubly occupy a molecular orbital. Based on the estimated parameters18,19,20: t ~ 2.5 eV to 3.0 eV and U ~ 6 eV to 10 eV, we mainly used U = 2t and 3t in our studies. Two accurate numerical methods, exact diagonalization (ED)21 and constrained-path Monte Carlo (CPMC)22,23, are employed to simulate the model Hamiltonian (1). In the followings, the results presented are obtained by the CPMC method, except where explicitly noted otherwise.

the energy difference between carbon atoms with and without hydrogen bonds, which is due to different electron-negativity of carbon and hydrogen. Notice that the on-site Hubbard U is different from the effective Coulomb interaction Ueff12,13, which stands for the energetic cost to doubly occupy a molecular orbital. Based on the estimated parameters18,19,20: t ~ 2.5 eV to 3.0 eV and U ~ 6 eV to 10 eV, we mainly used U = 2t and 3t in our studies. Two accurate numerical methods, exact diagonalization (ED)21 and constrained-path Monte Carlo (CPMC)22,23, are employed to simulate the model Hamiltonian (1). In the followings, the results presented are obtained by the CPMC method, except where explicitly noted otherwise.

Results

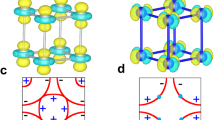

Four hydrocarbon molecules investigated in our studies are displayed in Fig. 1, which are defined as C14H10 (a), C30H18 (b), C22H14 − A (c) and C22H14 − B (d). The former three correspond to the hydrocarbon molecules in phenanthrene, 1, 2 : 8, 9-dibenzopentacene and picene, respectively. C22H14 − B, which has a similar structure to C30H18 with both linear and angular fusion of benzene rings, is degenerate with C22H14 − A from our first-principle calculations, suggesting its possible existence in alkali-metal-doped picene.

In the noninteracting limit, i.e. U = 0, the electronic spectrum can be easily obtained by diagonalizing the quadratic Hamiltonian in Eq. (1). The energy difference between LUMO and LUMO+1, E(LUMO+1)-E(LUMO), is shown in Fig. 2 as a function of  for different molecules. It is obviously that the electronic spectrum depends sensitively on the molecule structure. For C14H10 and C22H14 − A with phenanthrene edge-type termination, the energy difference decreases monotonically with increasing

for different molecules. It is obviously that the electronic spectrum depends sensitively on the molecule structure. For C14H10 and C22H14 − A with phenanthrene edge-type termination, the energy difference decreases monotonically with increasing  ; while for C30H18 and C22H14 − B, it decreases first with increasing

; while for C30H18 and C22H14 − B, it decreases first with increasing  and then turns to increase with

and then turns to increase with  beyond a certain

beyond a certain  . The energy differences between LUMO and LUMO+1 in phenanthrene and picene from the first-principle calculations are estimated to be about 0.1 eV and 0.07 eV (see Supplementary Information), respectively, which are consistent with the results for C14H10 at

. The energy differences between LUMO and LUMO+1 in phenanthrene and picene from the first-principle calculations are estimated to be about 0.1 eV and 0.07 eV (see Supplementary Information), respectively, which are consistent with the results for C14H10 at  and for C22H14 − A at

and for C22H14 − A at  . This indicates that PAHs could be well described by the model Hamiltonian (1) with

. This indicates that PAHs could be well described by the model Hamiltonian (1) with  .

.

Magnetic property

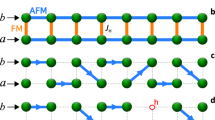

First, we show the spin phase diagram of different molecules in Fig. 3 at U = 2t. Here, we present the results for the neutral molecule (the total number of pπ-electrons Ne equals the total number of carbon atoms NC) and charged molecules with 1, 2, 3 and 4 added electrons. The total spin S of the ground state is obtained by comparing the energies in different spin sectors. The molecules not shown in Fig. 3 always lie in the lowest spin states (S = 0 for even Ne and S = 1/2 for odd Ne). One can clearly see that for the two electrons added cases, the total spin S switches from 0 to 1 at a certain critical  for all molecules shown in Fig. 1. Moreover, for the molecule C30H18, the four electrons added case shows a transition from the high spin (S = 1) state to the low spin (S = 0) state as

for all molecules shown in Fig. 1. Moreover, for the molecule C30H18, the four electrons added case shows a transition from the high spin (S = 1) state to the low spin (S = 0) state as  is increased. At U = 3t, the phase diagram is similar to the one presented in Fig. 3. Besides, we find that C30H18 with three electrons added changes from being in the low spin (S = 1/2) state to the high spin (S = 3/2) state at

is increased. At U = 3t, the phase diagram is similar to the one presented in Fig. 3. Besides, we find that C30H18 with three electrons added changes from being in the low spin (S = 1/2) state to the high spin (S = 3/2) state at  .

.

Spin phase diagram for charged hydrocarbon molecules as displayed in Fig. 1 at U = 2t.

The total spin S of the ground state is shown for a combination of molecule structure, charge and  . The integer in the bracket denotes the number of electrons added to the neutral molecule.

. The integer in the bracket denotes the number of electrons added to the neutral molecule.

The spin polarized state for the charged molecules with two added electrons at large  provides a unified explanation of local spins observed for PAHs superconductors in the normal states, with an average number of added electrons per molecule nave ~ 31,2,3,4,5. In alkali-metal-doped PAHs, the added electrons come from alkali-metal atoms intercalated between the stacked molecules9,10,11. Therefore, local inhomogeneous intercalation of alkali-metal atoms in the molecular solid may induce a local nonuniform charge distribution on different molecules. If two electrons happen to lie on the same molecule, the spin polarized state is favored, which contributes to the high magnetic susceptibility observed in experiments.

provides a unified explanation of local spins observed for PAHs superconductors in the normal states, with an average number of added electrons per molecule nave ~ 31,2,3,4,5. In alkali-metal-doped PAHs, the added electrons come from alkali-metal atoms intercalated between the stacked molecules9,10,11. Therefore, local inhomogeneous intercalation of alkali-metal atoms in the molecular solid may induce a local nonuniform charge distribution on different molecules. If two electrons happen to lie on the same molecule, the spin polarized state is favored, which contributes to the high magnetic susceptibility observed in experiments.

Now the question arising is why the Curie-Weiss behavior of magnetic susceptibility is only observed when nave is larger than two1,3. This issue can be addressed by studying the effect of long range Coulomb interaction on the ground state of charged molecules with two added electrons. An inclusion of NN Coulomb interaction  (V denotes the strength of screened NN Coulomb repulsion) to the Hamiltonian (1) indicates that the energy difference between the high spin (S = 1) state and the low spin (S = 0) state increases with increasing V, as shown in Table I. One can observe that this energy difference becomes positive for V ≥ 0.4t and V ≥ 0.1t on C14H10 and C22H14 − A, respectively, suggesting that the low spin state is more stable when the NN Coulomb interaction is not all screened out. Considering the fact that electronic screening decreases with decreasing the metallicity of the molecular solid, it was expected that when nave is not large enough, NN Coulomb interaction is not screened out, making the low spin state more stable than the spin polarized state.

(V denotes the strength of screened NN Coulomb repulsion) to the Hamiltonian (1) indicates that the energy difference between the high spin (S = 1) state and the low spin (S = 0) state increases with increasing V, as shown in Table I. One can observe that this energy difference becomes positive for V ≥ 0.4t and V ≥ 0.1t on C14H10 and C22H14 − A, respectively, suggesting that the low spin state is more stable when the NN Coulomb interaction is not all screened out. Considering the fact that electronic screening decreases with decreasing the metallicity of the molecular solid, it was expected that when nave is not large enough, NN Coulomb interaction is not screened out, making the low spin state more stable than the spin polarized state.

. Statistical errors are in the last digit and shown in the parentheses

. Statistical errors are in the last digit and shown in the parenthesesPair binding property

In a strongly correlated electronic system, electron pairing may be induced either by a purely electronic mechanism or by the interplay of electron-electron interaction and electron-phonon coupling. The effect of electronic correlations on the superconductivity can be explored by examining the pair binding energy, which is defined as: Δi = 2Ei−Ei−1− Ei+1 with Ei representing the ground state energy for the charged molecule having i added electrons18. In this notation, a positive Δi implies that an effective attraction between added electrons can be produced through a charge disproportionation process between the two molecules: (i) + (i) → (i − 1) + (i + 1), meaning that it is energetically favorable to have two molecules with i − 1 and i + 1 added electrons each rather than two molecules with i added electrons each. We have calculated the pair binding energy Δi (i = 1 and 3) for all molecules as shown in Fig. 1 and the results show that it is always negative in the whole parameter regime for C14H10, C22H14 − A and C22H14 − B (see Supplementary Information). In Fig. 4, we show Δ1 and Δ3 for C30H18 as a function of  . It is interesting to see that both Δ1 and Δ3 take positive values at U = 2t and U = 3t for

. It is interesting to see that both Δ1 and Δ3 take positive values at U = 2t and U = 3t for  , demonstrating that electron pair is favored in the C30H18 molecular solid at nave = 1.0 and nave = 3.0. The positive Δ1 and Δ3 actually represent the energy gain due to the formation of bounded S = 1 doubly-charged C30H18 and bounded S = 0 quadruply-charged C30H18, respectively, when two electrons are added to the neutral or already doubly-charged molecules. A similar pairing process was suggested to be responsible for superconductivity seen in alkali-meta-doped C60, but it occurs for U > 3.3t18.

, demonstrating that electron pair is favored in the C30H18 molecular solid at nave = 1.0 and nave = 3.0. The positive Δ1 and Δ3 actually represent the energy gain due to the formation of bounded S = 1 doubly-charged C30H18 and bounded S = 0 quadruply-charged C30H18, respectively, when two electrons are added to the neutral or already doubly-charged molecules. A similar pairing process was suggested to be responsible for superconductivity seen in alkali-meta-doped C60, but it occurs for U > 3.3t18.

The effective attraction between added electrons resulted from the positive pair binding energy may lead to various charge density-wave, magnetic and superconducting states, depending on the details of interactions between electrons around the Fermi level (including the intermolecular interaction which has not been considered in our present study)24. In the case that instability to superconductivity is predominant, it is expected that the positive pair binding energy has a contribution to the formation of Cooper pairs. In the potassium-doped 1,2:8,9-dibenzopentacene, superconductivity was observed for 3.0 ≤ nave ≤ 3.55. Therefore, a positive Δ3 at large epsilon suggests that electron correlation might have a contribution to the formation of Cooper pairs. The bounded S = 0 state for quadruply-charged C30H18 is consistent with possible s-wave superconductivity in dibenzopentacene, of which the magnetic susceptibility shows a similar temperature dependence to the one in barium-doped phenanthrene, where s-wave superconductivity has been demonstrated by specific-heat measurements25. At  , our calculations with an inclusion of nearest-neighbor Coulomb interaction

, our calculations with an inclusion of nearest-neighbor Coulomb interaction  show that both Δ1 and Δ3 are increased by a finite V, indicating that the effective attractive interaction between electrons is robust against the long range Coulomb interaction.

show that both Δ1 and Δ3 are increased by a finite V, indicating that the effective attractive interaction between electrons is robust against the long range Coulomb interaction.

Discussion

Our numerical calculations show that there exists strong magnetic instability in the charged molecules of PAHs, especially for the even number of added electrons, which provides a reasonable explanation of local spins observed in experiments. In alkali-metal-doped dibenzopentacene, electron correlation may produce an effective attraction between added electrons through charge disproportionation in different C30H18 molecules. This is not only useful for understanding the superconducting mechanism in alkali-metal-doped dibenzopentacene, but also encouraging for the search of higher Tc PAH superconductors with longer chains of benzene rings. Experimental test on the spin state and charge distribution in PAHs can be compared with our predictions and also is crucial for clarifying the magnetic and superconducting properties of charged PAHs.

Methods

To study the magnetic and pair binding properties of PAHs, we have mainly used the CPMC method22,23 to compute the ground state of interacting pπ-electrons described in the model Hamiltonian (1). The basic strategy of the CPMC method is to project the ground-state wave function from an initial wave function (with correct quantum numbers corresponding to the ground state) by a branching random walk in an overcomplete space of constrained Slater determinants, which have positive overlaps with a known trial wave function. For more technique details we refer to Refs. [22, 23]. Since the total spin S of the ground state is unknown a priori, we first applied the CPMC method to project the lowest eigenstates of Hamiltonian (1) in different spin sectors (S, Sz) and then defined the one with lowest energy as the ground state. In our calculations, the free-electron wave function, given by Eq. (1) at U = 0 and represented by a single Slater determinant, was chosen as the initial and trial wave functions. This choice achieves the projection in a certain spin sector with  . Here, N↑ and N↓ denote the total numbers of electrons with spin up and spin down, respectively.

. Here, N↑ and N↓ denote the total numbers of electrons with spin up and spin down, respectively.

To justify the accuracy of the CPMC program, in Fig. S1 and Fig. S2 (see Supplementary Information) we compare the pair binding energy obtained from both ED and CPMC methods on C14H10 at U = 2t and U = 3t. We observe that the CPMC data are in good agreement with the ED results and the systematic error induced by the constraint of Slater determinant is small. In Ref. [22], extensive benchmark calculations for the one-band Hubbard model defined on a square lattice also showed that in the weak and intermediate coupling regimes, the CPMC method can present us accurate energy and reliable correlations of the ground state.

References

Mitsuhashi, R. et al. Superconductivity in alkali-metal-doped picene. Nature 464, 76–79 (2010).

Kubozono, Y. et al. Metal-intercalated aromatic hydrocarbons: a new class of carbon-based superconductors. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 16476–16493 (2011).

Wang, X. F. et al. Superconductivity at 5 K in alkali-metal-doped phenanthrene. Nature Communications 2, 507–513 (2011).

Wang, X. F. et al. Superconductivity in A1.5phenanthrene (A = Sr,Ba). Phys. Rev. B 84, 214523 (2011).

Xue, M. et al. Superconductivity above 30 K in alkali-metal doped hydrocarbon. Scientific Reports 2, 389–392 (2012).

Hebard, A. F. et al. Superconductivity at 18 K in potassium-doped C60. Nature 350, 600–601 (1991).

Ganin, A. Y. et al. Bulk superconductivity at 38 K in a molecular system. Nature Mater. 7, 367–371 (2008).

Ganin, A. Y. et al. Polymorphism control of superconductivity and magnetism in Cs3C60 close to the Mott transition. Nature 466, 221–225 (2010).

Nomura, Y. et al. Ab initio derivation of electronic low-energy models for C60 and aromatic compounds. Phys. Rev. B 85, 155452 (2012).

Kosugi, T. et al. First-principles structural optimization and electronic structure of the superconductor picene for various potassium doping levels. Phys. Rev. B 84, 214506 (2011).

de Andres, P. L. et al. Ab initio electronic and geometrical structures of tripotassium-intercalated phenanthrene. Phys. Rev. B 84, 144501 (2011).

Giovannetti, G. & Capone, M. Electronic correlation effects in superconducting picene from ab initio calculations. Phys. Rev. B 83, 134508 (2011).

Kim, M. et al. Density functional calculations of electronic structure and magnetic properties of the hydrocarbon K3picene superconductor near the metal-insulator transition. Phys. Rev. B 83, 214510 (2011).

Kato, T. et al. Strong Intramolecular Electron-Phonon Coupling in the Negatively Charged Aromatic Superconductor Picene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 077001 (2011).

Subedi, A. & Boeri, L. Vibrational spectrum and electron-phonon coupling of doped solid picene from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 84, 020508(R) (2011).

Casula, M. et al. Intercalant and Intermolecular Phonon Assisted Superconductivity in K-Doped Picene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 137006 (2011).

Kato, T. et al. Electron-phonon coupling in negatively charged acene- and phenanthrene-edge-type hydrocarbon crystals. J. Chem. Phys. 116, 3420–3429 (2002).

Chakravarty, S. et al. Electron Correlation Effects and Superconductivity in Doped Fullerenes. Science 254, 970–974 (1991).

Castro Neto, A. H. et al. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 109–162 (2009).

Wehling, T. O. et al. Strength of Effective Coulomb Interactions in Graphene and Graphite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 236805 (2011).

Lin, H. Q. & Gubernatis, J. E. Exact Diagonalization Methods for Quantum Systems. Computers in Physics 7 (4), 400 (1993).

Zhang, S. W. et al. Constrained path Monte Carlo method for fermion ground states. Phys. Rev. B 55, 7464 (1997).

Huang, Z. B. et al. Quantum Monte Carlo study of Spin, Charge and Pairing correlations in the t − t′ − U Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 64, 205101 (2001).

Chakravarty, S. & Kivelson, S. A. Electronic mechanism of superconductivity in the cuprates, C60 and polyacenes. Phys. Rev. B 64, 064511 (2001).

Ying, J. J. et al. s-wave superconductivity in barium-doped phenanthrene as revealed by specific-heat measurements. Phys. Rev. B 85, 180511(R) (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by MOST 2011CB922200, the Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants Nos. 10974047 and 11174072 and by SRFDP under Grant No. 20104208110001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.B.H. developed the numerical codes and performed the calculations. C.Z. carried out the first-principle calculations. Z.B.H. and H.Q.L. analyzed the data, wrote the paper and led the project.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Magnetic instability and pair binding in aromatic hydrocarbon superconductors

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareALike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Z., Zhang, C. & Lin, HQ. Magnetic instability and pair binding in aromatic hydrocarbon superconductors. Sci Rep 2, 922 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00922

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00922

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

for C14H10 (solid line), C22H14 − A (dashed line), C22H14 − B (dotted line) and C30H18 (dashed-dotted line).

for C14H10 (solid line), C22H14 − A (dashed line), C22H14 − B (dotted line) and C30H18 (dashed-dotted line).

for C30H18.

for C30H18.