Aging causes significant changes in visual perception, even in healthy people with no dementia or eye disease. As a result, many people struggle with simple daily activities as they age—things like driving safely, walking on uneven ground or negotiating stairs. Unfortunately, the mechanisms underlying age-related defects in perception are not well understood. Few studies have investigated the kinds of perceptual changes that occur through adulthood, particularly in older individuals, and even fewer have correlated those changes with brain function and eye movements.

But visual illusions have begun to provide some important insights in this area. Because we know that specific ocular or brain mechanisms mediate certain illusions, how our perception of them alters with age provides clues to how aging affects related brain cell populations. These shifts also lay plain that the existence of illusions is not just an accident or mistake of evolution. Illusions are part and parcel of our perception, and their degradation with age—which, let's be clear, makes the observer see the world in a more accurate and less illusory fashion—indicates that some aspects of illusory perception may have enhanced survival. Such an advantage becomes less important as brain function decreases in senescence.

Other types of visual impairments can help us understand neurodegeneration in the aging brain. Yet illusions may stand out above other visual biomarkers because older vision scientists—themselves experts in illusory perception—are acutely aware when their own observations do not match those of their younger experimental test subjects. It is one thing to have back pain, or to lose the ability to run an eight-minute mile, or to have trouble memorizing phone numbers. Those problems are all annoying. But when an amazing new illusion fails to work for your brain—especially when all your younger colleagues are agog—it is downright unnerving. It certainly focuses the mind and makes those neuroscientists wonder if they may be slowly losing theirs.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Lothar Spillmann, currently a visiting professor at the National Taiwan University, is a case in point. Spillmann spent most of his career at the University of Freiburg. Then he turned 65—the German university system's mandatory retirement age—and he had to hit the road to find continued employment abroad. Now 77, he remains a highly productive scientist and serves as an international elder statesman for perceptual science.

As a world leader in his field, Spillman has discovered a number of important misperceptions, including the Ouchi-Spillmann illusion, which produces a motion effect that we described previously in this column. So you can imagine Spillmann's concern when—the same year he retired in Germany—he discovered he was blind to perhaps the most significant illusion of the past two decades, Akiyoshi Kitaoka's Rotating Snakes [below].

SNAKES ON A BRAIN

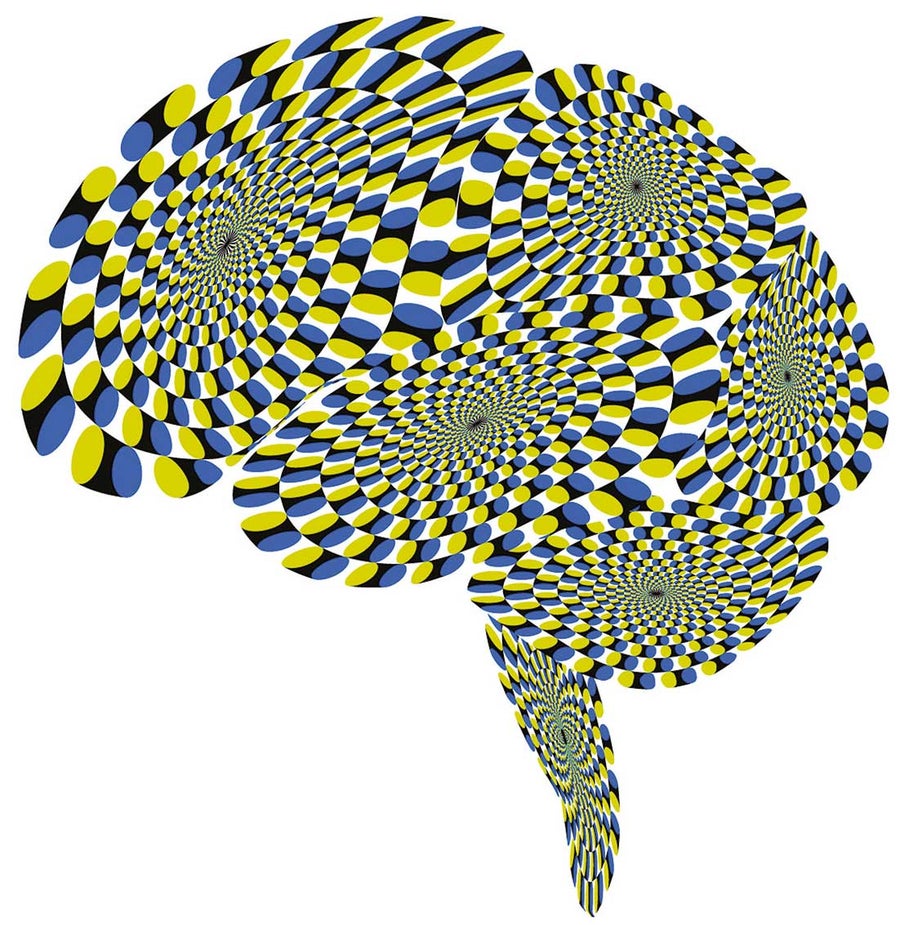

When most people look at Rotating Snakes—rendered here in the shape of a brain by neuroscientist and engineer Jorge Otero-Millan—they perceive illusory motion. Geneticist and painter Alex Fraser and biologist Kimerly J. Wilcox, both then at the University of Cincinnati, first discovered this type of illusory motion in 1979, when they elicited the effect from repetitive spiral arrangements of sawtooth-edged shapes shaded light to dark. Fraser and Wilcox’s illusion was not nearly as effective as Rotating Snakes, developed more than 20 years later by Akiyoshi Kitaoka, but it did spawn a number of related illusions. This family of perceptual phenomena is characterized by the periodic placement of colored or grayscale patches of particular brightnesses. In 2005 neuroscientist Bevil R. Conway, then at Harvard Medical School, and his colleagues showed that Kitaoka’s illusory layout activates motion-sensitive neurons in the visual cortex, providing a neural basis for why most of us perceive rotation: we see the snakes spin because our visual neurons respond as if we are in the presence of actual motion.

In our own research with Otero-Millan, now a postdoctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins University, we found a direct relation between the perception of this rotation and the production of transient eye movements, including eyelid blinks and tiny involuntary eye jerks called microsaccades. Could age-related eye-motion failures explain why Spillmann and other older people have trouble seeing the “snakes” rotate? Maybe. But the Ouchi-Spillmann illusion—which Spillmann does still perceive—also appears to rely on eye movements. So it may be that certain visual processes, such as motion perception, motion adaptation or brightness perception, which are also susceptible to aging, have a differential involvement in one illusion versus the other. Or the age-related loss may reflect a combination of oculomotor and visual deficits.

CREDIT: JORGE OTERO-MILLAN

ILLUSIONS ACROSS THE AGES

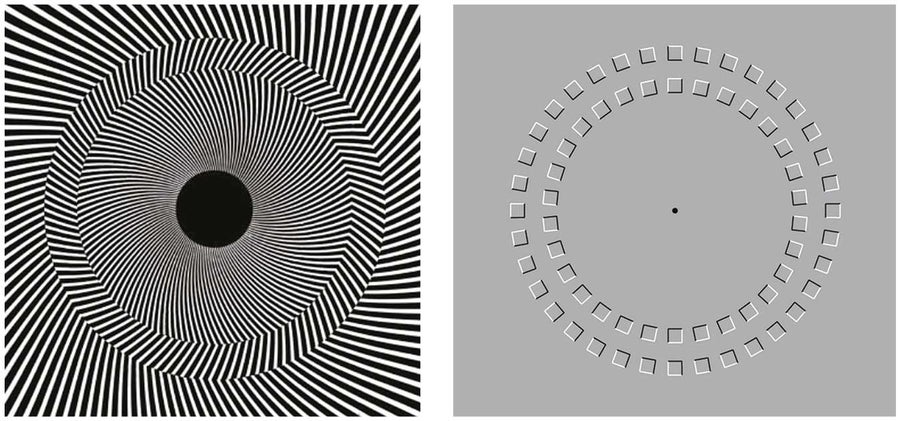

In a 2009 study, psychologists Jutta Billino, Kai Hamburger and Karl Gegenfurtner of the Justus Liebig University Giessen in Germany tested 139 subjects—old and young—with a battery of illusions involving motion, including Rotating Snakes. They found that older subjects perceived less illusory rotation than younger ones, not only in Rotating Snakes but also in the Rotating-Tilted-Lines illusion, depicted above on the left.

To experience this illusion, move your head forward and backward as you fixate on the central area (or alternatively, hold your head still and move the screen or page you are reading). Most young adults see illusory motion: the ring spins against the central and surrounding regions. But the Pinna illusion, which was the first to create a rotating motion effect (right), works for most observers, regardless of age: as you move your head (or the image) forward and back, you will see the inner and outer rings rotate in opposite directions.

Whatever causes these various percepts to change with age is not simply a failure to perceive illusory movement but reflects ongoing changes in the brain or visual system. We hope these findings will lead to future research and a more nuanced grasp of the mechanisms underlying our perception of real and illusory motion, as well as the specific neurodegenerative effects of aging on different brain circuits.

CREDIT: FROM “A NEW MOTION ILLUSION: THE ROTATING-TILTED-LINES ILLUSION,” BY SIMONE GORI AND KAI HAMBURGER, IN PERCEPTION, VOL. 35, NO. 6; JUNE 2006 (Rotating-Tilted-Lines illusion); FROM “A NEW VISUAL ILLUSION OF RELATIVE MOTION,” BY BAINGIO PINNA AND GAVIN J. BRELSTAFF, IN VISION RESEARCH, VOL. 40, NO. 16; JULY 1, 2000 (Pinna illusion)