Abstract

Imminent development of offshore wind farms on the outer continental shelf of the United States has led to significant concerns for marine wildlife. The scarcity of empirical data regarding fish species that may utilize development sites, further compounded by the novelty of the technology and inherent difficulty of conducting offshore research, make identification and assessment of potential stressors to species of concern problematic. However, there is broad potential to mitigate putatively negative impacts to seasonal migrants during the exploration and construction phases. The goal of this study was to establish baseline information on endangered Atlantic Sturgeon in the New York Wind Energy Area (NY WEA), a future offshore development site. Passive acoustic transceivers equipped with acoustic release mechanisms were used to monitor the movements of tagged fish in the NY WEA from November 2016 through February 2018 and resulted in detections of 181 unique individuals throughout the site. Detections were highly seasonal and peaked from November through January. Conversely, fish were relatively uncommon or entirely absent during the summer months (July–September). Generalized additive models indicated that predictable transitions between coastal and offshore habitat were associated with long-term environmental cues and localized estuarine conditions, specifically the interaction between photoperiod and river temperature. These insights into the ecology of marine-resident Atlantic Sturgeon are crucial for both defining monitoring parameters and guiding threat assessments in offshore waters and represent an important initial step towards quantitatively evaluating Atlantic Sturgeon at a scale relevant to future development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Offshore wind endeavors are increasingly being regarded as readily-available sources of renewable energy1,2,3,4,5. Favorable domestic policy, coupled with the rapid development and maturation of overseas wind energy markets during the last two decades, has created impetus for the exploitation of offshore wind energy resources in the US6,7,8,9. The majority of near-term activities are concentrated in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions of the US where a number of projects in federal waters of the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) have been proposed or are in the planning stages, dependent on clean energy goals and initiatives of individual states.

Imminent development of the OCS has led to concerns about the potential for offshore wind farms to negatively impact marine ecosystems and fauna10,11,12,13. The novelty of the technology and the inherent difficulty of conducting offshore research make identification and assessment of potential stressors to marine wildlife problematic12,14. Impacts of operational offshore wind farms—both positive and negative—are often locally influenced and contingent on specific site, species’ spatial and temporal distribution, and management objectives; however, there is broad potential to mitigate negative impacts during the exploration and construction phases through spatial and temporal considerations, particularly for migratory species that may only utilize a development site on a seasonal basis15,16,17.

Studies regarding the impacts of offshore wind development have largely focused on marine mammals and seabirds18,19,20,21 and there is a relative scarcity of information regarding marine fish species22,23,24,25. The lack of empirical data, particularly for commercially important and federally protected marine fish species, underscores the need for targeted research to better quantify the likely effects of offshore wind energy development14,16,26. Baseline data collection and modeling are critical for future decision making and regulation in wind energy areas and are especially important when designing impact assessments for species of concern with limited or no existing information on offshore distribution or abundance16.

The federally protected Atlantic Sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus) is a species of concern that may occupy marine habitat allocated for future offshore wind development. Atlantic Sturgeon are an anadromous, long-lived species with a broad distribution along the Atlantic Coast of the US. Atlantic Sturgeon are highly migratory and exhibit a complex life-history that is dependent on access to both freshwater and marine environments, contingent on life-stage. Although adults undertake obligatory migrations into natal river systems for spawning purposes, the majority of the late-juvenile and adult life-stages are spent in coastal marine waters27. Delayed sexual maturity and the subsequent increase in reproductive output that occurs at later ages indicate that a focus on the reduction of mortality in the marine resident life-stages of Atlantic Sturgeon is necessary to restore depleted populations28,29,30. Despite this, basic knowledge of Atlantic Sturgeon in marine waters is limited and, consequently, the identity and magnitude of current and emerging threats are often difficult to assess.

In the New York Bight (NYB), limited scientific and commercial fisheries data suggest that Atlantic Sturgeon spend significant time in near-coastal marine waters31,32,33,34,35,36. Documented movements and aggregation areas of Atlantic Sturgeon in the NYB are concentrated along the coasts of New York and New Jersey and have been observed within 13-km of the shoreline33. Commercial fisheries bycatch of Atlantic Sturgeon has been observed in offshore areas that are beyond recognized aggregation sites34,37. The Hudson River stock makes up a large part of the coastal bycatch of Atlantic Sturgeon in the NYB (42.2–46.3%38); however, the mixing of coast-wide genetic stocks that occurs in marine waters emphasizes the potential for emerging, localized threats (i.e., offshore wind farm development) to affect multiple stocks39,40.

The New York Wind Energy Area (NY WEA; Equinor, Lease OCS-A 0512), located between Long Island and the coast of New Jersey, is an offshore wind-lease area in the exploration and site assessment phase of development that will ostensibly host active construction in the near-future; as such, the area provides a unique opportunity to study the spatial and temporal trends of Atlantic Sturgeon in a future offshore wind energy site. Because effective management of Atlantic Sturgeon requires an understanding of marine movements and habitat use, the identification of the temporal and spatial trends of Atlantic Sturgeon in the NY WEA will provide important baseline information regarding habitat use and environmental preferences in offshore marine waters. These data are critical to informing management decisions in the NY WEA and are necessary to inform required statutory consultations and impact assessments under the Endangered Species Act and the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act41,42. Consequently, the goal of this study was to establish threshold information on endangered Atlantic Sturgeon in a future offshore wind energy site, with the specific objectives of identifying: (1) spatiotemporal trends in offshore occurrence; (2) residency in the NY WEA; and (3) environmental predictors of offshore movement.

Methods

Study site

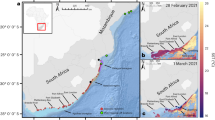

The NY WEA encompasses approximately 79,350 acres of offshore euhaline habitat in the NYB region of the western Atlantic Ocean, east of the Hudson Shelf Valley (Fig. 1). Located in federal waters off the coast of New York and New Jersey, the site extends 22–48 km (11.5–24.0 nm) southeast of Long Island, New York, and forms an expanding wedge positioned between the Ambrose to Nantucket (eastbound) and Hudson Canyon to Ambrose (northwest-bound) traffic lanes. The Cholera Bank feature, located adjacent to the westernmost end of the NY WEA, was removed from the original lease area43. Water depths in the NY WEA range from 23 to 41 m and generally increase away from shore in a southeasterly direction44. The bottom habitat is characterized as relatively flat and primarily composed of sandy sediments, although isolated patches of gravelly, muddy sand exist44,45. Seasonal fluctuations are strong in the study area and bottom temperatures range from 2 to 22 °C. Thermal stratification between bottom and surface waters generally occurs from April to August, with turnover during the fall months44.

Map of the New York Wind Energy Area study site (NY WEA; Equinor, Lease OCS-A 0512) and inset showing the relative location in federal waters of the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of New York and New Jersey. Transceiver station locations, assumed 600-m detection radii, and 1-m depth isoclines within the NY WEA are indicated. The transceiver array operated throughout the entire course of the study (November 10, 2016–February 5, 2018) with the exception of a single station indicated by (^) which was not recovered during the final download cruise; data for this station were unavailable for the period of August 4, 2017–February 5, 2018. Locations of relevant environmental monitoring stations are shown (NH = Entrance to New York Harbor, NOAA NDBC Station 44065; BB = Coastal Barnegat Bay, NOAA NDBC Station 44091; MP = Coastal Montauk Point, NOAA National NDBC Station 44017; OS = Offshore New York, NOAA NDBC Station 44025; HR = Hudson River below Poughkeepsie, New York, USGS Gauging Station 01372058).

Fish sampling

All methods for the capture and handling of Atlantic Sturgeon in this study were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and were authorized by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS; Endangered Species Permits 16422 and 20351), New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (Endangered/Threatened Species Scientific License 336), and Stony Brook University’s (SBU) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IRB-1022451–4).

Marine resident Atlantic Sturgeon [i.e., juvenile (500–1,000 mm fork length [FL]), sub-adult (1,000–1,300 mm FL), and adult (>1,300 mm FL) life-stages, based on NMFS permitting definitions] were opportunistically sampled in May 2016–2018 and October 2017 during targeted research tows aboard the RV Seawolf. Tows occurred peripheral to the study site and targeted known marine aggregations located off the Rockaway Peninsula, New York; sampling relied on previously described trawl gear33,34. Tows occurred in relatively shallow waters (8–20 m) at speeds of 3.0–3.5 knots for short durations (5–15 min) in order to maximize capture efficiency while minimizing the stress placed on captured fish.

Atlantic Sturgeon were immediately sorted from the catch and transferred to an onboard live-well where they were allowed to recover. All fish were then examined for internal and external tags. If none was found, a passive integrated transponder tag was inserted into the body musculature beneath the fourth dorsal scute and an external dart tag was inserted near the dorsal fin base. Measurements of total length, FL, and weight were recorded. Age-at-capture was estimated using the von Bertalanffy growth function46 and parameter estimates for Atlantic Sturgeon from the NYB distinct population segment (L∞ = 278.87, K = 0.057, t0 = −1.2747). A uniquely-coded VEMCO (Halifax, Nova Scotia) acoustic transmitter (V-16 6 H; 69 kHz; tag delay 70–150 s; estimated battery life = 3,650 d) was then surgically implanted into each individual fish48,49. Following surgeries, fish were returned to the live-well and monitored for 5–10 min until they had fully recovered before being released near their original capture site.

Passive acoustic telemetry

In November 2016, a stationary array consisting of 24 acoustic-release transceivers (VEMCO VR2AR) with omnidirectional hydrophones was deployed throughout the NY WEA to monitor movements of acoustically tagged fish (Fig. 1). Submerged transceivers were attached to anchored buoys and deployed so that they were suspended approximately 2 m from the seabed. Transceivers were placed in a grid pattern with nearest-adjacent transceiver stations located less than 4 km apart [mean (range) = 3.43 (2.87–3.94) km]. Preliminary range testing at transceivers was accomplished using a transponding hydrophone (VEMCO VR100) and revealed an average maximum detection radius of approximately 600 m (range = 200–1,000 m), depending on sea state. Previous studies utilizing acoustic receiver arrays in coastal waters have assumed a 600 m detection radius based on high detection rates of tags at similar ranges (e.g., ~65% at 600 m and a maximum range of 1,400 m50). Although the western-most transceiver was not directly positioned in the NY WEA, the assumed detection radius of 600 m overlapped with the study site and was therefore included in analyses.

An onboard tracking receiver and transponding hydrophone permitted surface communication with individual transceivers; acoustic-release and recovery of transceivers was facilitated through remote detachment of the transceiver from a sacrificial anchor during download and maintenance. Transceivers with acoustic release mechanisms allowed for deeper and longer deployments in offshore marine waters without the need for diver retrieval. Transceiver array download and maintenance cruises occurred in August 2017 and February 2018. The transceiver array operated throughout the entire course of the study (November 10, 2016–February 5, 2018) with the exception of a single station which was not recovered during the final download cruise; data for this station were unavailable for the period of August 4, 2017–February 5, 2018 (Fig. 1).

Telemetry data were carefully reviewed to identify and remove any spurious detections that were obvious based on the spatial and temporal chronology of individual fish51. Data management and analysis were primarily performed in R52. Additional detections of Atlantic Sturgeon that were tagged by SBU researchers during previous sampling efforts were included in analyses to increase the robustness of the study (~380 previously tagged Atlantic Sturgeon assumed at-large in fall 201653).

Environmental data

Potential environmental predictors were compiled from a variety of sources and matched to daily unique counts of Atlantic Sturgeon detections in the NY WEA. Environmental variables were selected based on putative biological significance to Atlantic Sturgeon as reported in previous studies as well as availability and completeness of datasets during the time-period of interest. Daily photoperiod and moon-fraction illumination were calculated using the R package “suncalc”52. Sea surface temperatures were compiled from environmental monitoring stations maintained by the National Data Buoy Center (NDBC) in nearshore-coastal and offshore waters, including: the entrance to New York Harbor (NOAA NDBC Station 44065), coastal Barnegat Bay, New Jersey (NOAA NDBC Station 44091), coastal Montauk Point, New York (NOAA National NDBC Station 44017), and offshore New York (NOAA NDBC Station 44025; Fig. 1). Hudson River environmental data, including temperature and discharge, were obtained from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) gauging station located at river kilometer (rkm) 115 in the lower Hudson River below Poughkeepsie, New York (USGS 01372058; Fig. 1). Average hourly bottom temperatures in the NY WEA were compiled from transceiver records; from these, monthly point values at transceiver locations were interpolated onto a raster surface using an inverse distance weighted technique in ArcGIS to simplify visual comparison of monthly temperatures in the NY WEA. Because anadromous Atlantic Sturgeon migrate between heterogeneous environments, pair-wise differences between water temperatures were also examined to explore potential triggers of movement between habitats.

Residency and movement

Periods of residency and movement were calculated using the behavioral event qualifier in the R package “V-Track”53,54,55. A residence event was defined as a minimum of two successive detections of an individual at a single transceiver station over a minimum period of two hrs. Residence events were terminated by either a detection of the individual on another transceiver station or a period of 12 hrs without detection (i.e., time-out period). Movement events were defined as non-residence events (i.e., movements of an individual between two transceivers) and were limited to non-residence events of less than five days. Rate of movement (ROM) was calculated using a transceiver-distance matrix that assumed direct distance movements and a 600 m detection radius for each transceiver. When available, calculations were aided by detections of Atlantic Sturgeon from cooperative arrays located outside of the study area.

Generalized additive models

Unique daily counts of Atlantic Sturgeon in the NY WEA were modeled using generalized additive models (GAMs)56. All GAMs were built in the R package “mgcv”57 using thin plate splines58,59. A log-link function with a quasi-Poisson error distribution was used to account for overdispersion in the count data. Independence of daily counts was assumed to be valid based on previously reported movement rates of Atlantic Sturgeon that suggest that daily mixing can occur. The initial model included photoperiod, moon-fraction illuminated, water temperatures, and discharge, and considered complexity up to first-order interactions. Stepwise backwards elimination of explanatory variables was performed to determine a minimally adequate model using minimization of the generalized cross validation (GCV) criterion to guide the process. AIC is not available for quasi-Poisson models, and GCV is an acceptable alternative in subset regression60,61. During model selection, GCV scores were compared with and without an explanatory variable to determine which terms to remove. Smoothing functions were replaced by linear terms if the estimated degrees of freedom approached a value of one, suggesting that a smooth was essentially a straight line62. Because the water temperatures for the New York Harbor and Hudson River estuary were highly correlated predictors (r2 = 0.91), only the latter was used to capture potential cues in river temperature associated with Atlantic Sturgeon movement. As a test of the quality of the selection process, the final and full models were compared using an F-ratio test to determine if the final (i.e., selected) model explained significantly less of the residual error compared to the full model62. A significant result would indicate that the final model explained less of the residual error than the full model and that the final model was under-parameterized.

Results

Fish sampling and acoustic telemetry

Atlantic Sturgeon (n = 133) were captured via targeted bottom trawling and tagged with acoustic transmitters during sampling cruises in May 2016 (n = 40), May 2017 (n = 81), and October 2017 (n = 12). The size range of the tagged fish was 619 to 2,050 mm FL, with a mean FL of 855 mm. Tagged fish were representative of juvenile (n = 114), sub-adult (n = 17), and adult (n = 2) life-stages, with age-at-capture estimates ranging from 4 to 28 years. Detections of Atlantic Sturgeon tagged during this study as well as at-large fish tagged by SBU researchers during previous sampling efforts were included in analyses to increase the robustness and scope of the study53.

Telemetry data indicated that Atlantic Sturgeon were present in the NY WEA during array operation. Total confirmed detections for Atlantic Sturgeon ranged from 1 to 310 detections per individual, with a total of 5,490 valid detections of 181 unique individuals. Detections in the NY WEA were representative of Atlantic Sturgeon tagged during the study (n = 39; 1,028 detections; Table 1) as well as at-large Atlantic Sturgeon tagged by SBU researchers during previous sampling efforts (n = 142; 4,462 detections; Supplementary Table S1). Atlantic Sturgeon occurred throughout the study site and were detected on all transceivers in the array (Fig. 2); importantly, Atlantic Sturgeon were observed on the most distal transceiver station, located 44.3 km offshore (21 total detections of 5 unique fish). Total counts and detections of unique fish were highest nearer to shore and appeared to decrease with distance from shore. Counts at each station ranged between 21–909 total detections and 4–59 unique detections of Atlantic Sturgeon.

Atlantic Sturgeon were regularly detected in the NY WEA throughout the study period and 55 individuals were observed in the site during multiple years. During 2016 and 2018, transceivers were only operational in the study site for a short period (November 10–December 31, 2016 and January 1–February 5, 2018) but 87 unique fish (2,098 detections) and 30 unique fish (761 detections) were detected, respectively. In 2017, the array was operational for the entire year and 126 Atlantic Sturgeon (2,631 detections) were observed in the study site. Monthly counts of individuals in the NY WEA were highest during the months of November, December, and January, and peaked in December 2016 (n = 58) (Figs 3 and 4). Importantly, two years of data are available for these months and similar abundances were observed for both datasets (e.g., relatively high abundances of Atlantic Sturgeon occurred during November and December 2016–2017 and January 2017–2018). Atlantic Sturgeon were relatively uncommon (i.e., <2 individuals detected) or entirely absent from the NY WEA during July, August, and September (Figs 3 and 4).

Monthly counts of unique Atlantic Sturgeon (represented by graduated symbols) detected at unique acoustic transceiver stations in the New York Wind Energy Area study site (Equinor, Lease OCS-A 0512) from November 2016 through January 2018. Monthly point values of average bottom temperature were compiled from transceiver metadata. The transceiver array operated throughout the entire course of the study with the exception of a single station indicated by (^) which was not recovered during the final download cruise; data for this station were unavailable for the months of August 2017–February 2018.

Within the NY WEA, both temporal and spatial variation in unique counts of Atlantic Sturgeon were observed (Fig. 4). The majority of individual fish were detected on transceivers located nearer to shore except during months of relatively high abundance when fish were more widely distributed throughout the array. The highest observed abundance of Atlantic Sturgeon at a single station (n = 22; 23.4 km from shore) occurred in November 2017; however, during this month individuals were observed in the study site >40 km from shore, demonstrating the wide distribution of fish in the NY WEA. During the months of December and January, fish were present and evenly distributed across the majority of transceivers in the NY WEA and in December 2016 Atlantic Sturgeon were detected on all transceivers in the array. Average monthly bottom temperatures observed in the study site ranged from 2.1 to 19.0 °C, with local minimum temperatures in February–March and local maximum temperatures in August–October (Fig 4). Evident temperature stratification between bottom and surface waters in the study site was observed April–November (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Atlantic Sturgeon residence and non-residence events at transceiver stations in the New York Wind Energy Area study site (Equinor, Lease OCS-A 0512) from November 10, 2016–February 5, 2018. Residence events are defined as a minimum of two successive detections of an individual at a single transceiver station over a minimum period of two hrs. Residence events are completed by either a detection of the individual on another transceiver station or a period of 12 hrs without detection. Non-residence events (i.e., movements of an individual between two transceivers) were limited to periods of less than five days.

Residency and movement

Residence events at individual transceiver stations in the NY WEA were uncommon (n = 22) and were only observed on five transceivers during the study period, with the majority of residence behaviors associated with near-shore stations in the NY WEA (Fig. 5). The station with the highest number of observed residence events (n = 8) was located 24.9 km from shore, and no residence events were observed beyond 30.1 km from shore. Residence events were of short duration [mean (SD) = 10.1 (14.0) hrs; range = 2.1–70.1 hrs] and the maximum ROM observed between stations was 0.86 m/s, although slower rates were common [mean (SD) = 0.31 (0.20) m/s]. By assuming the maximum observed ROM of 0.86 m/s and maximum straight-line distance of 40.6 km between stations from the transceiver-distance matrix, the minimum transit time for an Atlantic Sturgeon through the NY WEA at its longest point was estimated to be 13.1 hrs. This suggests that daily mixing could occur and, consequently, that the assumption of independence for daily counts used to model the data was valid.

Interaction between photoperiod and water temperature in the Hudson River estuary, New York, during 2017. Circle size represents the daily unique count of Atlantic Sturgeon in the New York Wind Energy Area study site (Equinor, Lease OCS-A 0512). Water temperature is from the USGS Gauging Station 01372058 at Hudson River below Poughkeepsie, New York. Winter = December 1–February 28; Spring = March 1–May 31; Summer = June 1–August 31; Fall = September 1–November 28.

Generalized additive model

The final, simplified GAM model contained a smooth term for the interaction between Hudson River estuary water temperature and photoperiod and a linear term for river discharge as predictors of unique daily counts of Atlantic Sturgeon in the NY WEA:

where UDC is unique daily count of Atlantic Sturgeon in the NY WEA, HRtemp is daily mean water temperature (°C) in the lower Hudson River, HRdischarge is daily mean discharge (ft3/s) in the lower Hudson River, P is daily photoperiod (hrs), and s() indicates a smoother was used. The final model explained 61.0% of the deviance and had a GCV score of 0.9407. No significant difference was found between the final and full model (F7.04,409.23 = 1.58, p = 0.1389), providing evidence that the selection process identified an appropriately complex model.

Exploration of the relationship between daily abundance of Atlantic Sturgeon in the NY WEA and the two-way interaction term above allows for clarification of the model structure (Fig. 6). Both temperature and photoperiod terms are cyclical (i.e., the same value can occur during a positive or negative trend) and out of phase. As water temperatures in the Hudson River decreased below 20 °C during the fall months along with decreasing daily photoperiod, daily counts of Atlantic Sturgeon in the NY WEA were observed to increase and reached a maximum as water temperature in the Hudson River approached its annual minimum (~0.0 °C). Conversely, as water temperatures in the Hudson River increased during the spring and into the summer months along with increasing daily photoperiod, detections of Atlantic Sturgeon in the NY WEA decreased and fish were entirely absent when temperature was at its summer maximum. While water temperature in the Hudson River was strongly correlated to photoperiod (r2 = 0.49), there was a notable temporal lag of ~ 35 days, presumably because of the high heat capacity of water. During this lag in the late summer, Atlantic Sturgeon were not detected in the NY WEA when temperatures in the river were near their maximum, despite the decreasing trend in photoperiod. The response curve for the linear discharge term had a clear, decreasing trend, and suggests that high daily abundance of Atlantic Sturgeon in the NY WEA was more likely in the fall and winter during periods of low river discharge (less than 20,000 ft3/s; Supplementary Fig. S3).

Discussion

This study provides benchmark information regarding the incidence and seasonality of marine-resident Atlantic Sturgeon use of offshore waters in the NY WEA and, importantly, identifies potential estuarine drivers of offshore occurrence. With the development of offshore wind energy in the United States comes the recognized need to prioritize offshore research and monitoring in the context of ecological risk assessment and mitigation; here, we establish effective baseline criteria regarding spatial and temporal trends of Atlantic Sturgeon within the putative area of effect—an obligatory prerequisite for evaluating the impact of activities during all stages of offshore wind energy development. Furthermore, this study demonstrates the effectiveness of acoustic-release transceivers for discerning cryptic behaviors of species of concern in an offshore wind energy site through the targeted monitoring of acoustically tagged individuals.

Overall, the results of this study suggest that offshore distribution of Atlantic Sturgeon in the NY WEA is highly seasonal. Observations of fish on the acoustic array broadly corroborate and expand the current knowledge of marine movements in the mid-Atlantic Bight31,32,33,34,37,38. However, the fine-scale documentation of Atlantic Sturgeon trends in the NY WEA and the identification of putative migratory pathways beyond the extent of traditional survey data may have important implications on species conservation. Consistent spatial and temporal trends of Atlantic Sturgeon occurrence were evident from telemetry data and indicated expansion into deeper, offshore waters of the NY WEA during the fall and winter months. High incidences of Atlantic Sturgeon during the winter were observed in both years, with a marked increase in unique counts and total detections in November and December. The absence of Atlantic Sturgeon in the NY WEA during the summer months, particularly from June through September, suggests a putative shift to nearshore habitat and corresponds with periods of known-residence in shallow, coastal waters that are associated with juvenile and sub-adult aggregations as well as adult spawning migrations29,55,63,64,65.

Despite the recent focus on coastal research, as well as the consequent designation of in-river critical habitat (n = 31 Critical Habitat Units)66, the offshore trends and distribution of Atlantic Sturgeon remain relatively unknown and the biological and physical features essential for their conservation in marine habitats have not been identified. The results of this study should help define monitoring parameters in offshore waters and guide future assessments in marine wind energy areas. An important finding from the telemetry data was that Atlantic Sturgeon used the majority of habitat available to them within the NY WEA. Individual counts and total detections of Atlantic Sturgeon were highest on transceivers located in shallow waters and exhibited a generally decreasing trend with increased depth and distance from shore. Although limited observations of adult Atlantic Sturgeon have been described on shelf waters at depths of up to 40 m32, the ubiquity of Atlantic Sturgeon documented throughout the study site was unexpected and suggests that the distribution and habitation of these fish in marine waters is greater than previously assumed. Throughout the range, research is needed to further characterize the extent of the offshore distribution of Atlantic Sturgeon; however, these results demonstrate the importance of targeted studies in marine waters where more traditional survey- or fisheries-dependent methodologies may underestimate habitat use, particularly at intermediate scales or at the boundaries of the known distribution of highly migratory fish.

The influence of environmental factors on Atlantic Sturgeon counts in the NY WEA suggests that transitions between coastal and offshore habitat are predictable and associated with long-term cues and localized estuarine conditions. Anadromous fish populations are known to undertake extensive annual migrations to optimize temporally predictable foraging and spawning conditions67,68; these migrations are assumed to be governed, at least in part, by seasonal and ontogenetic responses to complex abiotic factors67. In sturgeon species, photoperiod and water temperature (and, to a lesser extent, discharge) are recognized as factors that act to modulate migratory strategies69,70. Although the specific mechanisms driving movements and ontogenetic migrations of Atlantic Sturgeon are not well known, clinal variations in abiotic conditions have been broadly associated with temporal distribution and habitat selection35,51,71. The final GAM model indicates that a small subset of abiotic factors provide context-dependent cues regarding the timing of offshore migration. Day-length (i.e., photoperiod) is a reliable long-term trigger of migration that is largely autonomous of annual variation in environmental conditions, while both river temperature and discharge provide short-term signals that result from dynamic, localized conditions. Further evaluation of these cues as predictors of offshore migration is necessary on both a regional and coast wide scale; regardless, the identification of specific abiotic factors that trigger migration and, consequently, offshore distribution has important management implications for monitoring and conservation efforts in future wind energy sites.

Movements and distributions of Atlantic Sturgeon in marine habitats are widely acknowledged to be indicative of preferential selection for covarying environmental properties that are encountered in-situ35,72. Interestingly, although we considered various marine predictors from both within and outside of the study area, terms used as proxies of marine environmental conditions were not represented in the final model. The elimination of these terms during model selection was informative and suggests that in-river conditions have a significantly greater influence on annual offshore transitions than those encountered while at sea, at least on the scale considered in this study. Likewise, coastal or latitudinal movements, which might otherwise have been inferred from the influence of pair-wise differences in nearby marine conditions (e.g., Barnegat Bay, New Jersey, or Montauk Point, New York), were not indicated by the final model. Although telemetry detections from this study were limited and do not provide evidence of relocations outside of the NY WEA, the seasonal occurrence of marine-migrant Atlantic Sturgeon in near-shore and coastal waters is well documented and corresponds to periods when few or no fish were detected in the study site. In the Hudson River estuary, specifically, marine-migrant life-stages are present from April until the end of November63,64,65 and aggregate in adjacent coastal waters during May, June, September, and October before dispersing34,35, which is suggestive of temporal and spatial resource partitioning.

Preferential distribution of Atlantic Sturgeon on bottom types associated with high prey density, most notably sand and gravelly-sand substrates, has been inferred based on commercial bycatch and stomach content analysis31,73 but a clear linkage between foraging behavior and resource utilization in marine waters has yet to be determined. The presence of Atlantic Sturgeon over sand-dominated substrates throughout the NY WEA is informative and adds to the literature regarding marine habitat use; however, it does not provide direct evidence of foraging activities in the area. Additional information regarding vertical distributions of Atlantic Sturgeon and, particularly, the relationship between swimming depth and bottom depth could provide further indication as to habitat use74; however, the current criteria for defining foraging habitat in marine environments remain largely circumstantial or unknown, and further characterization of ecological correlates of foraging area use with environmental parameters is necessary.

The delineation of behavior modes from telemetry data allows for more informative conclusions regarding perceived habitat selection within the NY WEA as well as explicit guidance for identifying areas of concern at a scale relevant to future development. Over the course of this study, residence events were uncommon and of short duration, despite the use of a relatively non-restrictive time constraint (i.e., minimum residency period of two hrs) to discern any apparent spatial trends in behavior. Importantly, residence behaviors were generally limited to shallow water sites (i.e., depth < 30 m), which suggests the increased potential for negative interactions to occur in these areas during development activities. Site-fidelity of Atlantic Sturgeon in offshore waters is likely highly-variable based on resource availability and, moreover, may occur at a broad spatial scale beyond the scope of this study, as suggested by the migratory life-history of Atlantic Sturgeon and limited observations of mesoscale distribution32,35. Individual direct-distance movement rates observed in the NY WEA are comparable to estimates associated with adult foraging behavior in estuarine habitats75,76; however, because of the necessary assumption of direct movement, further classification of these behaviors as directional (i.e., transitory) or non-directional (i.e., foraging) is problematic. Regardless, the delineation of sub-seasonal behavior modes is an important step in linking habitat and resource utilization in marine waters.

While biotelemetry itself is not a new technique77, the use of acoustic release mechanisms to complement telemetry data collection is a recent development that allows research in deeper offshore areas where conventional array maintenance and data retrieval are problematic78. To our knowledge, the current study is the first to use transceivers equipped with acoustic release mechanisms to monitor fish behavior at an offshore wind energy site and may represent a new paradigm for future assessments. Passive acoustic monitoring techniques, coupled with acoustic release technology, provide long-term functionality and situational flexibility as necessary to inform baseline ecological characterization and subsequent ecological impact assessments in offshore wind energy leases. The recent proliferation of long-term acoustic tagging programs along the Atlantic coast of the US not only allows for the possibility of supplemental detections and increased sample size (e.g., the incorporation of previously tagged individuals into the current study) but also illustrates the need for an integrated approach to allow for among-site or comparative analyses. Although the primary focus of our study was to provide baseline pre-construction data, the methodology used could be modified or extended to provide data throughout all phases of development, including informing behavioral changes or fine-scale spatial shifts in distribution of Atlantic Sturgeon over time.

The findings of this study indicate that mitigation of potentially negative impacts of wind energy development, such as multiple-pulse sound sources, is possible through spatial and temporal avoidance during periods of increased Atlantic Sturgeon incidence. Detections of individuals on all transceivers in the study array provide strong evidence that Atlantic Sturgeon use a large amount of the habitat available to them in NY WEA, albeit on a highly seasonal basis. While previous studies have primarily associated the extreme noise from pile-driving during the construction phase with negative impacts to fish assemblages79,80, there is still large uncertainty in the literature regarding the physiological effects or behavioral responses of fish to these disturbances. Likewise, data are limited in regards to response distances and areas of potential effect16. The low relative abundance of Atlantic Sturgeon in offshore waters of the NY WEA that was observed during the summer months, when sub-adult and adult life-stages were putatively aggregated in riverine or more near-coastal habitats, suggests that the negative impacts of pile-driving activities on Atlantic Sturgeon could be reduced or largely avoided by incorporating data-directed management measures during the planning stages. Conversely, an increased emphasis on impact monitoring is suggested during periods of increased Atlantic Sturgeon abundance during the winter months—particularly November, December, and January—if construction activities cannot be avoided.

From a more general management standpoint, the observed occurrence of Atlantic Sturgeon in offshore waters of the NY WEA underscores the importance of long-term monitoring to recovery efforts, particularly with regard to life-stages and habitats that may be underrepresented in the literature. While considerable research and management attention has recently focused on riverine and coastal waters81, empirical evaluations of Atlantic Sturgeon populations in marine waters are inadequate and limited by a lack of basic knowledge. Recent annual survival rate estimates for Atlantic Sturgeon are already below the suggested threshold for recovery35,82,83,84 and, despite a lack of information regarding the magnitude of emerging threats such as offshore wind energy development, it is apparent that even a moderate increase in mortality resulting from anthropogenic sources could negatively impact Atlantic Sturgeon stocks. Further characterization of the broad spatiotemporal trends of Atlantic Sturgeon in offshore waters are necessary to better define monitoring parameters and guide threat assessments in marine wind energy areas; regardless, this study represents an important initial step towards quantitatively evaluating Atlantic Sturgeon in marine waters at a scale relevant to future development.

Data Availability

Atlantic Sturgeon telemetry detections used in the current study are archived and publicly viewable on the Harvard Dataverse website: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/. The complete environmental datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Esteban, M. D., Diez, J. J., Lopez, J. S. & Negro, V. Why offshore wind energy? Renew. Energy 36, 444–450 (2011).

Panwar, N. L., Kaushik, S. C. & Kothari, S. Role of renewable energy sources in environmental protection: a review. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 15, 1513–1524 (2011).

United States Department of Energy. Wind Vision: A New Era for Wind Power in the United States. DOE/GO-102015-4557. (U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, 2015).

Gilman, P. et al. National Offshore Wind Strategy: Facilitating the Development of the Offshore Wind Industry in the United States. DOE/GO-102016-4866. (U.S. Department of Energy; U.S. Department of the Interior 2016).

Li, J. & Yu, X. Onshore and offshore wind energy potential assessment near Lake Erie shoreline: a spatial and temporal analysis. Energy 147, 1092–1107 (2018).

Kaldellis, J. K. & Kapsali, M. Shifting towards offshore wind energy—recent activity and future development. Energy Policy 53, 136–148 (2013).

Higgins, P. & Foley, A. The evolution of offshore wind power in the United Kingdom. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 37, 599–612 (2014).

Kota, S., Bayne, S. B. & Nimmagadda, S. Offshore wind energy: a comparative analysis of UK, USA and India. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 41, 685–694 (2015).

Davis, C., Bollinger, L. A. & Dijkema, G. P. J. The state of the states: data-driven analysis of the US Clean Power Plan. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 60, 631–652 (2016).

Gill, A. B. Offshore renewable energy: ecological implications of generating electricity in the coastal zone. J. Appl. Ecol. 42, 605–615 (2005).

Inger, R. et al. Marine renewable energy: potential benefits to biodiversity? An urgent call for research. J. Appl. Ecol. 46, 1145–1153 (2009).

Boehlert, G. W. & Gill, A. B. Environmental and ecological effects of ocean renewable energy development. Oceanography 23, 68–81 (2010).

Verfuss, U. K., Sparling, C. E., Arnot, C., Judd, A. & Coyle, M. Review of offshore wind farm impact monitoring and mitigation with regard to marine mammals. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 875, 1172–1182 (2016).

Vallejo, G. C. et al. Responses of two marine top predators to an offshore wind farm. Ecol. Evol. 7, 8698–8708 (2017).

Leonhard, S. B., Stenberg, C. & Støttrup, J. G. Effect of the Horns Rev 1 Offshore Wind Farm on Fish Communities: Follow-up Seven Years after Construction. (DTU Aqua National Institute of Aquatic Resources, 2011).

Bailey, H., Brookes, K. L. & Thompson, P. M. Assessing environmental impacts of offshore wind farms: lessons learned and recommendations for the future. Aquat. Biosyst. 10, 8 (2014).

Bergstrom, L. et al. Effects of offshore wind farms on marine wildlife—a generalized impact assessment. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/9/3/034012 (2014).

Drewitt, A. L. & Langston, R. H. W. Assessing the impacts of wind farms on birds. Ibis 148, 29–42 (2006).

Gilles, A., Scheidat, M. & Siebert, U. Seasonal distribution of harbor porpoises and possible interference of offshore wind farms in the German North Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 383, 295–307 (2009).

Thompson, P. M. et al. Framework for assessing impacts of pile-driving noise from offshore wind farm construction on a harbour seal population. Environ. Impact Asses. 43, 73–85 (2013).

Russell, D. J. F. et al. Avoidance of wind farms by harbor seals is limited to pile driving activities. J. Appl. Ecol. 53, 1642–1652 (2016).

Wahlberg, M. & Westerberg, H. Hearing in fish and their reactions to sounds from offshore wind farms. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 288, 295–309 (2005).

Kituchi, R. Risk formulation for the sonic effects of offshore wind farms on fish in the EU region. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 60, 172–177 (2010).

Bergstrom, L., Sundqvist, F. & Bergstrom, U. Effects of an offshore wind farm on temporal and spatial patterns in the demersal fish community. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 485, 199–210 (2013).

Reubens, J. T., Pasotti, F., Degraer, S. & Vincx, M. Residency, site fidelity and habitat use of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) at an offshore wind farm using acoustic telemetry. Mar. Environ. Res. 90, 128–135 (2013).

Furness, R. W., Wade, H. M. & Masden, E. A. Assessing vulnerability of marine bird populations to offshore wind farms. J. Environ. Manage. 119, 56–66 (2013).

Smith, T. I. J. The fishery, biology, and management of Atlantic Sturgeon, Acipenser oxyrhynchus, in North America. Environ. Biol. Fishes 4, 61–72 (1985).

Boreman, J. Sensitivity of North American sturgeons and paddlefish to fishing mortality. Environ. Biol. Fishes 48, 399–405 (1997).

Van Eenennaam, J. P. & Doroshov, S. I. Effects of age and body size on gonadal development of Atlantic Sturgeon. J. Fish Biol. 53, 624–637 (1998).

Atlantic Sturgeon Status Review Team. Status review of Atlantic Sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus). Report to National Marine Fisheries Service, Northeast Regional Office (2007).

Stein, A. B., Friedland, K. D. & Sutherland, M. Atlantic Sturgeon marine distribution and habitat use along the Northeastern Coast of the United States. Trans Am Fish Soc. 133, 527–537 (2004).

Erickson, D. L. et al. Use of pop-up satellite tags to identify oceanic-migratory patterns for adult Atlantic Sturgeon, Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus Mitchell, 1815. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 27, 356–365 (2011).

Dunton, K. J., Jordaan, A., McKown, K. A., Conover, D. O. & Frisk, M. G. Abundance and distribution of Atlantic Sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus) within the Northwest Atlantic Ocean, determined from five fishery-independent surveys. Fish. Bull. 108, 450–465 (2010).

Dunton, K. J. et al. Marine distribution and habitat use of Atlantic Sturgeon in New York lead to fisheries interactions and bycatch. Mar. Coast. Fish. 7, 18–32 (2015).

Melnychuk, M. C., Dunton, K. J., Jordaan, A., McKown, K. A. & Frisk, M. G. Informing conservation strategies for the endangered Atlantic Sturgeon using acoustic telemetry and multi-state mark–recapture models. J. Appl. Ecol. 54, 914–925 (2017).

Breece, M. W., Fox, D. A., Haulsee, D. E., Wirgin, I. I. & Oliver, M. J. Satellite driven distribution models of endangered Atlantic Sturgeon occurrence in the mid-Atlantic Bight. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 75, https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsx187 (2017).

Stein, A. B., Friedland, K. D. & Sutherland, M. Atlantic Sturgeon marine bycatch and mortality on the continental shelf of the Northeast United States. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 24, 171–183 (2004).

Wirgin, I., Maceda, L., Grunwald, C. & King, T. L. Population origin of Atlantic Sturgeon Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus by-catch in U.S. Atlantic coast fisheries. J. Fish Biol. 86, 1251–1270 (2015).

Dunton, K. J. et al. Genetic mixed-stock analysis of Atlantic Sturgeon Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus in a heavily exploited marine habitat indicates the need for routine genetic monitoring. J. Fish Biol. 80, 207–217 (2012).

O’Leary, S. J., Dunton, K. J., King, T. L., Frisk, M. G. & Chapman, D. D. Genetic diversity and effective number of breeders of Atlantic Sturgeon, Acipenser oxyrhinchus oxyrhinchus. Conserv. Genet. 15, 1173–1181 (2014).

McDonald, J. Critical habitat designation under the Endangered Species Act: a road to recovery? Environ. Law 28, 671–700 (1998).

Robbins, K. Recovery of an endangered provision: untangling and reviving critical habitat under the Endangered Species Act. Buffalo Law Rev. 58, 1–31 (2010).

Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. Commercial Wind Lease Issuance and Site Assessment Activities on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf Offshore New York: Revised Environmental Assessment. (U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Office of Renewable Energy Programs, 2016).

Guida, V. et al. Habitat Mapping and Assessment of Northeast Wind Energy Areas. OCS Study BOEM 2017-088 (U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, 2017).

Poti, M., Kinlan, B. P. & Menza, C. Chapter 2: Bathymetry. In A Biogeographic Assessment of Seabirds, Deep Sea Corals and Ocean Habitats of the New York Bight: Science to Support Offshore Spatial Planning (eds Menza, C. et al.) 9–32 (NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS NCCOS 141, 2012).

von Bertalanffy, L. A quantitative theory of organic (inquiries on growth laws, II). Hum. Biol. 10, 181–213 (1938).

Dunton, K. J. et al. Age and growth of Atlantic Sturgeon in the New York Bight. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 36, 62–73 (2016).

Moser, M. L. et al. A Protocol for Use of Shortnose and Atlantic Sturgeons. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-OPR-18 (2000).

Boone, S. S. et al. Evaluation of four suture materials for surgical incision closure in Siberian Sturgeon. Trans. Am. Fish Soc. 142, 649–659 (2013).

Kilfoil, J. P., Wetherbee, B. M., Carlson, J. K. & Fox, D. A. Targeted catch-and-release of prohibited sharks: sand tigers in coastal Delaware waters. Fisheries 42, 281–287 (2017).

Ingram, E. C. & Peterson, D. L. Annual spawning migrations of adult Atlantic Sturgeon in the Altamaha River, Georgia. Mar. Coast. Fish. 8, 595–606 (2016).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria (2018).

Dunton, K. J. Population dynamics of juvenile Atlantic Sturgeon, Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus, within the northwest Atlantic Ocean. Doctoral Dissertation. Stony Brook University (2014).

Campbell, H. A., Watts, M. E., Dwyer, R. G. & Franklin, C. E. V-Track: software for analysing and visualising animal movement from acoustic telemetry detections. Mar. Freshwater Res. 63, 815–820 (2012).

Breece, M. W., Fox, D. A. & Oliver, M. J. Environmental drivers of adult Atlantic Sturgeon movement and residency in Delaware Bay. Mar. Coast. Fish. 10, 269–280 (2018).

Hastie, T. J. & Tibshirani, R. J. Generalized Additive Models. (Chapman & Hall, 1990).

Wood, S. N. Mixed GAM Computation Vehicle with Automatic Smoothness. R package version 1.8-27 (2011).

Duchon, J. Splines minimizing rotation-invariant semi-norms in Solobev spaces. In Construction Theory of Functions of Several Variables (eds Schempp, W. & Zeller, K.) 85–100 (Springer, 1977).

Wood, S. N. Thin plate regression splines. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B Stat. Methodol. 65, 95–114 (2003).

Golub, G. H., Health, M. & Wahba, G. Generalized cross-validation as a method for choosing a good ridge parameter. Technometrics 21, 215–223 (1979).

Burnham, K. P. & Anderson, D. R. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach. (Springer-Verlag, 1998).

Wood, S. N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R. (Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2006).

Dovel, W. L. & Berggren, T. J. Atlantic Sturgeon of the Hudson Estuary, New York. New York Fish Game J. 30, 140–172 (1983).

Bain, M. B. Atlantic and shortnose sturgeons of the Hudson River: common and divergent life history attributes. Environ. Biol. Fishes 48, 347–358 (1997).

Bain, M., Haley, N., Peterson, D., Waldman, J. R. & Arend, K. Harvest and habitats of Atlantic Sturgeon Acipenser oxyrinchus Mitchell, 1815 in the Hudson River estuary: lessons for sturgeon conservation. Bol. Inst. Esp. Oceanogr. 16, 43–54 (2000).

United States Office of the Federal Register. Endangered and threatened species; designation of Critical Habitat for the endangered New York Bight, Chesapeake Bay, Carolina and South Atlantic Distinct Population Segments of Atlantic Sturgeon and the threatened Gulf of Maine Distinct Population Segment of Atlantic Sturgeon. U.S. Office of the Federal Register 82, 39160–39274 (2017).

Gross, M. R., Coleman, R. M. & McDowall, R. M. Aquatic productivity and the evolution of diadromous fish migration. Science 239, 1291–1293 (1988).

Dingle, H. & Drake, V. A. What is migration? BioScience 57, 113–121 (2007).

Cech, J. J. Jr. & Doroshov, S. I. Environmental requirements, preferences, and tolerance limits of North American sturgeons. In Sturgeons and Paddlefish of North America (eds LeBreton, G. T. O., Beamish, F. W. H. & McKinley, S. R.) 73–86 (Springer, 2004).

Papoulious, D. M., DeLonay, A. J., Annis, M. L., Wildhaber, M. L. & Tillitt, D. E. Characterization of environmental cues for intitiation of reproductive cycling and spawning in shovelnose sturgeon Scaphirhynchus platorynchus in the Lower Missouri River, USA. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 27, 335–342 (2011).

Kieffer, M. C. & Kynard, B. Annual movements of shortnose and Atlantic Sturgeon in the Merrimack River, Massachusetts. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 122, 1088–1103 (1993).

Breece, M. W. et al. Dynamic seascapes predict the marine occurrence of an endangered species: Atlantic Sturgeon Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus. Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 725–733 (2016).

Johnson, J. H., Dropkin, D. S., Warkentine, B. E., Rachlin, J. W. & Andrews, W. D. Food habits of Atlantic Sturgeon off the central New Jersey coast. Trans. Am. Fish Soc. 126, 166–170 (1997).

Stokesbury, M. J. W. et al. Atlantic Sturgeon spatial and temporal distribution in Minas Passage, Nova Scotia, Canada, a region of future tidal energy extraction. PLoS ONE 11, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158387 (2016).

Hatin, D., Fortin, R. & Caron, F. Movements and aggregation areas of adult Atlantic Sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus) in the St Lawrence River estuary, Quebec, Canada. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 18, 586–594 (2002).

McClean, M. F., Simpfendorfer, C. A., Heupel, M. R., Dadswell, M. J. & Stokesbury, M. J. W. Diversity of behavioural patterns displayed by a summer feeding aggregation of Atlantic Sturgeon in the intertidal region of Minas Basin, Bay of Fundy, Canada. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 496, 59–69 (2014).

Johnson, J. H. Sonic tracking of adult salmon at Bonneville Dam, 1957. Fishery Bulletin 176 (United States Fish and Wildlife Service 1960).

Afonso, P. et al. Vertical migrations of a deep-sea fish and its prey. PLoS ONE 9, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0097884 (2014).

Popper, A. N. & Hastings, M. C. The effects of anthropogenic sources of sound on fish. J. Fish Biol. 75, 455–489 (2009).

Halvorsen, M. B., Casper, B. M., Matthews, F., Carlson, T. J. & Popper, A. N. Effects of exposure to pile-driving sounds on the lake sturgeon, Nile tilapia, and hogchoker. Proc. Royal Soc. B. 279, 4705–4714 (2012).

Hilton, E. J., Kynard, B., Balazik, M. T., Horodysky, A. Z. & Dillman, C. B. Review of the biology, fisheries, and conservation status of the Atlantic Sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus, Mitchill, 1815). J. Appl. Ichthyol. 32, 30–66 (2016).

Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. Estimation of Atlantic Sturgeon Bycatch in Coastal Atlantic Commercial Fisheries of New England and the Mid-Atlantic. Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, Washington, DC (2007).

Hightower, J. E., Loeffler, M., Post, W. C. & Peterson, D. L. Estimated survival of subadult and adult Atlantic Sturgeon in four river basins in the southeastern United States. Mar. Coast. Fish. 7, 514–522 (2015).

Dadswell, M. J. et al. The annual marine feeding aggregation of Atlantic Sturgeon Acipenser oxyrinchus in the inner Bay of Fundy: population characteristics and movement. J. Fish Biol. 89, 2107–2132 (2016).

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was provided in part by New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) and the U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) through Cooperative Agreement M16AC00003 between the U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and The Research Foundation for the State University of New York. In particular, we would like to extend our gratitude and thanks to Brian Hooker (BOEM) and Kim McKown (NYSDEC) for their role in administering project funding. Additional financial support for graduate studies was provided by the Hudson River Foundation for Science and Environmental Research through the Mark B. Bain Graduate Fellowship. We appreciate the invaluable field assistance provided by Justin Lashley, Kellie McCartin, Jill Olin, Joshua Zacharias, Catherine Ziegler, and Captain Christian Harter and the crew of the RV Seawolf.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.J.D., E.C.I. and M.G.F. conceived the study and secured project funding. E.C.I. and K.J.D. contributed to field work and data collection. E.C.I. and R.M.C. analyzed the results. E.C.I. drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and provided editorial comments on the draft manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ingram, E.C., Cerrato, R.M., Dunton, K.J. et al. Endangered Atlantic Sturgeon in the New York Wind Energy Area: implications of future development in an offshore wind energy site. Sci Rep 9, 12432 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48818-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48818-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.