Abstract

Mast seeding is one of the most intriguing reproductive traits in nature. Despite its potential drawbacks in terms of fitness, the widespread existence of this phenomenon suggests that it should have evolutionary advantages under certain circumstances. Using a global dataset of seed production time series for 219 plant species from all of the continents, we tested whether masting behaviour appears predominantly in species with low foliar nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations when controlling for local climate and productivity. Here, we show that masting intensity is higher in species with low foliar N and P concentrations, and especially in those with imbalanced N/P ratios, and that the evolutionary history of masting behaviour has been linked to that of nutrient economy. Our results support the hypothesis that masting is stronger in species growing under limiting conditions and suggest that this reproductive behaviour might have evolved as an adaptation to nutrient limitations and imbalances.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study can be found at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9863006.v1 and https://www.sciencebase.gov/catalog/item/5d9f7f49e4b036616294495d. Any use of trade, firm or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the US Government.

References

Salisbury, E. The Reproductive Capacity of Plants (Bell, 1942).

Silvertown, J. W. The evolutionary ecology of mast seeding in trees. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 14, 235–250 (1980).

Kelly, D. & Sork, V. L. Mast seeding in perennial plants: why, how, where? Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 33, 427–447 (2002).

Waller, D. M. Models of mast fruiting in trees. J. Theor. Biol. 80, 223–232 (1979).

Norton, D. A. & Kelly, D. Mast seeding over 33 years by Dacrydium cupressinum Lamb. (rimu) (Podocarpaceae) in New Zealand: the importance of economies of scale. Funct. Ecol. 2, 399–408 (1988).

Pearse, I. S., Koenig, W. D. & Kelly, D. Mechanisms of mast seeding: resources, weather, cues, and selection. New Phytol. 212, 546–562 (2016).

Espelta, J. M., Cortés, P., Molowny-horas, R., Sánchez-Humanes, B. & Retana, J. Masting mediated by summer drought reduces acorn predation in Mediterranean oak forests. Ecology 89, 805–817 (2008).

Espelta, J. M. et al. Beyond predator satiation: masting but also the effects of rainfall stochasticity on weevils drive acorn predation. Ecosphere 8, e01836 (2017).

Donaldson, J. S. Mast-seeding in the cycad genus Encephalartos: a test of the predator satiation hypothesis. Oecologia 94, 262–271 (1993).

Smith, C. C., Hamrick, J. L. & Kramer, C. L. The advantage of mast years for wind pollination. Am. Nat. 136, 154–166 (1990).

Fernández-Martínez, M., Belmonte, J., Maria Espelta, J. & Espelta, J. M. Masting in oaks: disentangling the effect of flowering phenology, airborne pollen load and drought. Acta Oecologica 43, 51–59 (2012).

Herrera, C., Jordano, P., Guitián, J. & Traveset, A. Annual variability in seed production by woody plants and the masting concept: reassessment of principles and relationship to pollination and seed dispersal. Am. Nat. 152, 576–594 (1998).

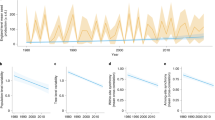

Pearse, I. S., LaMontagne, J. M. & Koenig, W. D. Inter-annual variation in seed production has increased over time (1900–2014). Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 284, 20171666 (2017).

Fernández-Martínez, M., Vicca, S., Janssens, I. A., Espelta, J. M. & Peñuelas, J. The role of nutrients, productivity and climate in determining tree fruit production in European forests. New Phytol. 213, 669–679 (2016).

Isagi, Y., Sugimura, K., Sumida, A. & Ito, H. How does masting happen and synchronize? J. Theor. Biol. 187, 231–239 (1997).

Ye, X. & Sakai, K. A new modified resource budget model for nonlinear dynamics in citrus production. Chaos Solitons Fract. 87, 51–60 (2016).

Pérez-Ramos, I. M., Ourcival, J. M., Limousin, J. M. & Rambal, S. Mast seeding under increasing drought: results from a long-term data set and from a rainfall exclusion experiment. Ecology 91, 3057–3068 (2010).

Fernández-Martínez, M., Vicca, S., Janssens, I. A., Espelta, J. M. & Peñuelas, J. The North Atlantic Oscillation synchronises fruit production in western European forests. Ecography 39, 864–874 (2016).

Sork, V. L., Bramble, J. & Sexton, O. Ecology of mast-fruiting in three species of North American deciduous oaks. Ecology 74, 528–541 (1993).

Perez-Ramos, I. M., Padilla-Díaz, C. M. & Koenig, W. D. & Marañón, T. Environmental drivers of mast-seeding in Mediterranean oak species: does leaf habit matter? J. Ecol. 103, 691–700 (2015).

Fernández-Martínez, M., Bogdziewicz, M., Espelta, J. M. & Peñuelas, J. Nature beyond linearity: meteorological variability and Jensen’s inequality can explain mast seeding behavior. Front. Ecol. Evol. 5, 134 (2017).

Wright, I. J. et al. The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature 428, 821–827 (2004).

Domingues, T. F. et al. Co-limitation of photosynthetic capacity by nitrogen and phosphorus in West Africa woodlands. Plant Cell Environ. 33, 959–980 (2010).

Field, C., Merino, J. & Mooney, H. A. Compromises between water-use efficiency and nitrogen-use efficiency in five species of California evergreens. Oecologia 60, 384–389 (1983).

Elser, J. J. et al. Nutritional constraints in terrestrial and freshwater food webs. Nature 408, 578–580 (2000).

Sardans, J. et al. Factors influencing the foliar elemental composition and stoichiometry in forest trees in Spain. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 18, 52–69 (2016).

Peñuelas, J. et al. The bioelements, the elementome, and the biogeochemical niche. Ecology 100, e02652 (2019).

Fernández-Martínez, M. et al. Nutrient-rich plants emit a less intense blend of volatile isoprenoids. New Phytol. 220, 773–784 (2018).

Camarero, J. J., Albuixech, J., López-Lozano, R., Casterad, M. A. & Montserrat-Martí, G. An increase in canopy cover leads to masting in Quercus ilex. Trees 24, 909–918 (2010).

Fernández-Martínez, M., Garbulsky, M., Peñuelas, J., Peguero, G. & Espelta, J. M. Temporal trends in the enhanced vegetation index and spring weather predict seed production in Mediterranean oaks. Plant Ecol. 216, 1061–1072 (2015).

Sala, A., Hopping, K., McIntire, E. J. B., Delzon, S. & Crone, E. E. Masting in whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) depletes stored nutrients. New Phytol. 196, 189–199 (2012).

Reekie, E. G. & Bazzaz, F. A. Reproductive effort in plants. 2. Does carbon reflect the allocation of other resources? Am. Nat. 129, 897–906 (1987).

Miyazaki, Y. et al. Nitrogen as a key regulator of flowering in Fagus crenata: understanding the physiological mechanism of masting by gene expression analysis. Ecol. Lett. 17, 1299–1309 (2014).

Han, Q., Kabeya, D., Iio, A., Inagaki, Y. & Kakubari, Y. Nitrogen storage dynamics are affected by masting events in Fagus crenata. Oecologia 174, 679–687 (2013).

Fujita, Y. et al. Low investment in sexual reproduction threatens plants adapted to phosphorus limitation. Nature 505, 82–86 (2014).

Sardans, J., Rivas-Ubach, A. & Peñuelas, J. The C:N:P stoichiometry of organisms and ecosystems in a changing world: a review and perspectives. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 14, 33–47 (2012).

Güsewell, S. N. P ratios in terrestrial plants: variation and functional significance. New Phytol. 164, 243–266 (2004).

McGroddy, M. E., Daufresne, T. & Hedin, O. L. Scaling of C:N:P stoichiometry in forests worldwide: implications of terrestrial redfield-type ratios. Ecology 85, 2390–2401 (2004).

Sardans, J. et al. Foliar and soil concentrations and stoichiometry of nitrogen and phosphorous across European Pinus sylvestris forests: relationships with climate, N deposition and tree growth. Funct. Ecol. 30, 676–689 (2016).

Eckstein, R. L. & Karlsson, P. S. Above-ground growth and nutrient use by plants in a subarctic environment: effects of habitat, life-form and species. Oikos 79, 311–324 (1997).

Fernández-Martínez, M., Vicca, S., Janssens, I. A., Martín-Vide, J. & Peñuelas, J. The consecutive disparity index, D, as measure of temporal variability in ecological studies. Ecosphere 9, e02527 (2018).

Martín-Vide, J. Notes per a la definició d’un índex de “desordre“ en pluviometria. Soc. Catalana Geogr. 7, 89–96 (1986).

Heath, J. P. Quantifying temporal variability in population abundances. Oikos 115, 573–581 (2006).

Losos, J. B. Phylogenetic niche conservatism, phylogenetic signal and the relationship between phylogenetic relatedness and ecological similarity among species. Ecol. Lett. 11, 995–1003 (2008).

Elser, J. J. et al. Global analysis of nitrogen and phosphorus limitation of primary producers in freshwater, marine and terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 10, 1135–1142 (2007).

LeBauer, D. S. & Treseder, K. K. Nitrogen limitation of net primary productivity in terrestrial ecosystems is globally distributed. Ecology 89, 371–379 (2008).

Erel, R. Flowering and fruit set of olive trees. Am. Soc. 133, 639–647 (2008).

Sardans, J. & Peñuelas, J. Drought changes phosphorus and potassium accumulation patterns in an evergreen Mediterranean forest. Funct. Ecol. 21, 191–201 (2007).

Elser, J. J. et al. Growth rate–stoichiometry couplings in diverse biota. Ecol. Lett. 6, 936–943 (2003).

Fernández-Martínez, M. et al. Nutrient availability as the key regulator of global forest carbon balance. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 471–476 (2014).

Nogueira, C. et al. Leaf nutrients, not specific leaf area, are consistent indicators of elevated nutrient inputs. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 400–406 (2019).

Smaill, S. J., Clinton, P. W., Allen, R. B. & Davis, M. R. Climate cues and resources interact to determine seed production by a masting species. J. Ecol. 99, 870–877 (2011).

Saura-Mas, S. & Lloret, F. Linking post-fire regenerative strategy and leaf nutrient content in Mediterranean woody plants. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 11, 219–229 (2009).

Kelly, D., Hart, D. & Allen, R. B. Evaluating the wind pollination benefits of mast seeding. Ecology 82, 117–126 (2001).

Fernández‐Martínez, M. et al. Towards a moss sclerophylly continuum: evolutionary history, water chemistry and climate control traits of hygrophytic mosses. Funct. Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.13443 (2019).

Fick, S. E. & Hijmans, R. J. WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4302–4315 (2017).

Harris, I., Jones, P. D. D., Osborn, T. J. J. & Lister, D. H. H. Updated high-resolution grids of monthly climatic observations—the CRU TS3.10 dataset. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 623–642 (2013).

Zhang, Y. et al. A global moderate resolution dataset of gross primary production of vegetation for 2000–2016. Sci. Data 4, 170165 (2017).

Kattge, J. et al. TRY—a global database of plant traits. Glob. Change Biol. 17, 2905–2935 (2011).

Maitner, B. S. et al. The bien r package: a tool to access the Botanical Information and Ecology Network (BIEN) database. Methods Ecol. Evol. 9, 373–379 (2017).

Rautio, P., Fürst, A., Stefan, K., Raitio, H. & Bartels, U. Sampling and analysis of needles and leaves (ICP Forests, 2010).

Cayuela, L. & Oksanen, J. Taxonstand: Taxonomic Standardization of Plant Species Names (2016).

Qian, H. & Jin, Y. An updated megaphylogeny of plants, a tool for generating plant phylogenies and an analysis of phylogenetic community structure. J. Plant Ecol. 9, 233–239 (2016).

R Development Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2018).

Revell, L. J. phytools: an R package for phylogenetic comparative biology (and other things). Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 217–223 (2012).

Tung Ho, L. S. & Ané, C. A linear-time algorithm for Gaussian and non-Gaussian trait evolution models. Syst. Biol. 63, 397–408 (2014).

Breheny, P. & Burchett, W. Visualization of regression models using visreg. R. J. 9:2, 56–71 (2017).

Bollback, J. P. SIMMAP: stochastic character mapping of discrete traits on phylogenies. BMC Bioinformatics 7, 88 (2006).

O’Meara, B. C., Ané, C., Sanderson, M. J. & Wainwright, P. C. Testing for different rates of continuous trait evolution using likelihood. Evolution 60, 922–933 (2006).

Thomas, G. H., Freckleton, R. P. & Székely, T. Comparative analyses of the influence of developmental mode on phenotypic diversification rates in shorebirds. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 273, 1619–1624 (2006).

Beaulieu, J. M., Jhwueng, D. C., Boettiger, C. & O’Meara, B. C. Modeling stabilizing selection: expanding the Ornstein–Uhlenbeck model of adaptive evolution. Evolution 66, 2369–2383 (2012).

Beaulieu, J. M. & O’Meara, B. OUwie: Analysis of Evolutionary Rates in an OU Framework (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Spanish Government project CGL2016-79835-P (FERTWARM), European Research Council Synergy Grant ERC-2013-726 SyG-610028 IMBALANCE-P and Catalan Government project SGR 2017-1005. M.F.-M. is a postdoctoral fellow of the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO). M.B. was supported by (Polish) NSF grants Sonatina 2017/24/C/NZ8/00151 and Uwertura 2018/28/U/NZ8/00003. This research was also supported by NSF grants DEB-1745496 630 to J.M.L. and DEB-1256394 to W.D.K.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.F.-M., I.P. and I.A.J. conceived the paper. M.F.-M and F.S. analysed the data. M.F.-M., J.S., J.P., I.P., W.D.K. and J.M.L. provided the data. All authors, including M.B., A.C., A.H.-P., G.V. and J.M.E. contributed substantially to the writing and discussion of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Plants thanks Shuli Niu, Ignacio Perez Ramos and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

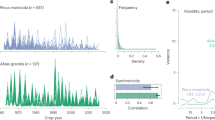

Extended Data Fig. 1 Evolutionary relationship between potential resource depletion coefficient (AR1) and temporal variability (PV) in seed production.

Evolutionary relationship between potential resource depletion coefficient (AR1) and temporal variability (PV) in seed production shown in a continuous trait phylogenetic reconstruction (a) and a phylomorphospace plot (b). Phylogenetic signal was estimated using Pagel’s lambda (λ). Potential resource depletion and variability in seed production were not evolutionary correlated. Negative values of AR1 indicate that potential resource depletion may happen, see Methods. N=219 species. t- value of the Pearson’s correlation was 1.95 (218 DF).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Mean differences (ΔAICc, second-order Akaike information criterion) between each of the model’s AICc and the model with the lowest AICc.

Mean differences (ΔAICc, second-order Akaike information criterion) between each of the model’s AICc and the model with the lowest AICc. Evolutionary models were Brownian motion (BM1, BMS) and generalised Ornstein-Uhlenbeck-based Hansen (OU1, OUM, OUMV), fitting “masting” and “non-masting” species-state and foliar nutrient concentrations (N: nitrogen, P: phosphorus, N:P: ratio N-to-P and, N×P: N times P (overall nutrient availability). Average AICc values were calculated using the subset of models in which none of them presented negative eigenvalues (sound models, n column: samples, independent simulations). Non-masting and masting columns indicate the number of species used in each category depending on the percentile of masting intensity used to classify species as non-masting (that is, higher than for example, 33%) and masting (that is, lower than for example, 66%). Models with ΔAICc lower than 2 (indicating equal performance) were highlighted. See Methods for further information.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Phylogenetic tree including the subset of low (non-masting) and high masting intensity (masting) species used to perform the generalised Ornstein-Uhlenbeck model results.

Phylogenetic tree including the subset of low (non- masting) and high masting intensity (masting) species used to perform the generalised Ornstein-Uhlenbeck model results presented in the main text (20th – 80th percentile thresholds for non-masting and masting species, Fig. 3, Extended Data Fig. 2 and Extended Data Fig. 4). The phylogenetic tree includes the estimated probability that ancestor nodes were masting or non-masting species (large circles) as pie charts. Small circles indicate the current category of the species. The ancestral character reconstruction was performed using 1000 stochastic character-mapped trees (see Methods for further information).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Estimated foliar nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) concentrations, N:P and N×P (overall nutrient availability) optimal values for masting and non-masting species.

Estimated foliar nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) concentrations, N:P and N×P (overall nutrient availability) optimal values for masting and non-masting species using OUMV and OUM models (see Methods for further information about the models), chosen based on the lowest ΔAICc estimating different state means for masting and non-masting species (Extended Data Fig. 2). Masting and non-masting species were classified depending on the percentile of masting intensity (for example, masting for higher than 66%, non-masting for lower than 33%, see subheaders within the table). Columns 2.5%, 50 and 97.5% indicate, for masting and non-masting species, the percentiles of the optimal values based on the sound models (without negative eigenvalues, n column: samples, independent simulations) used. M>N% indicate the percentage of models in which masting species presented average higher N, P, N:P or N×P optimal values than non-masting species. ΔM-N, followed by s.e.m (standard error of the mean), indicate the paired (across simulations) difference between optimal values in masting and non-masting species. P (two-sided t-test) shows the P-value of the paired t-test testing for differences in the mean optimal values of masting and non-masting species. ΔM-N%, followed by s.e.m., indicates the average percentual difference (geometric, paired differences) in mean optimal values between masting and non-masting species.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Evolutionary relationship between foliar N and P shown in a continuous trait phylogenetic reconstruction (a) and a phylomorphospace plot (b).

Evolutionary relationship between foliar N and P shown in a continuous trait phylogenetic reconstruction (a) and a phylomorphospace plot (b). Phylogenetic signal was estimated using Pagel’s lambda (λ). Foliar N and P concentrations were evolutionary correlated. N=168 species. t-value of the Pearson’s correlation was 5.38 (166 DF).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Map showing interannual variability (PV index) in mean annual precipitation (MAP) and site of origin of our fruit production data (blue dots).

Map showing interannual variability (PV index) in mean annual precipitation (MAP) and site of origin of our fruit production data (blue dots).

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fernández-Martínez, M., Pearse, I., Sardans, J. et al. Nutrient scarcity as a selective pressure for mast seeding. Nat. Plants 5, 1222–1228 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-019-0549-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-019-0549-y

This article is cited by

-

No evidence of carbon storage usage for seed production in 18 dipterocarp masting species in a tropical rain forest

Oecologia (2024)

-

Seed nutrient is more stable than leaf in response to changing multiple resources in an alpine meadow

Ecological Processes (2023)

-

Evolution of masting in plants is linked to investment in low tissue mortality

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Correlation between airborne pollen data and the risk of tick-borne encephalitis in northern Italy

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Masting is uncommon in trees that depend on mutualist dispersers in the context of global climate and fertility gradients

Nature Plants (2023)