Abstract

Background/Objectives

The recent upsurge in online food delivery options has reshaped the food market. The aim of this study was to examine between-city differences and within-city socioeconomic differences in the number of online meal delivery options, meal types, and meal prices.

Subjects/Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in three international cities within high-income countries. Across 10 sampled addresses in Chicago (USA), Amsterdam (The Netherlands), and Melbourne (Australia), meal delivery options provided by a major international meal delivery company were sampled. Bonferroni adjusted Chi2-tests were conducted to assess between-city differences as well as within-city socioeconomic differences in price levels.

Results

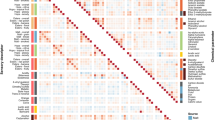

Across the 10 sampled addresses in each city, there were n = 1668 delivery options in Chicago, n = 1496 in Amsterdam and n = 1159 in Melbourne. In total, 10,220 keywords (representing 148 different meal types) were recorded across all 4323 delivery options. In all three cities, burgers, pizza and Italian were in the top 10 of most advertised meals. Compared with Amsterdam, healthy and meat-free meals were less commonly advertised in Chicago and Melbourne. In Chicago, the number of delivery options for addresses in the most disadvantaged and least disadvantaged neighborhoods were similar. In Amsterdam and Melbourne, a greater number of options was available for the addresses in the least disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Conclusions

This study highlights the vast number of meal delivery options individuals can source when at home via a meal delivery service, noting the number differs across and within cities. In each city, most food types available for delivery were not considered healthy.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Maimaiti M, Zhao X, Jia M, Ru Y, Zhu S. How we eat determines what we become: opportunities and challenges brought by food delivery industry in a changing world in China. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72:1282–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-018-0191-.

Pathak GS. Delivering the nation: the Dabbawalas of Mumbai. South Asia J South Asian Stud. 2010;33:235–57.

Platform-to-Consumer Delivery - worldwide | Statista Market Forecast. https://www.statista.com/outlook/376/100/platform-to-consumer-delivery/worldwide. Accessed 18 April 2019.

Online Food Delivery - worldwide | Statista Market Forecast. https://www.statista.com/outlook/374/100/online-food-delivery/worldwide. Accessed 18 April 2019.

Takeaway.com Press releases Q1 2019 trading update. https://corporate.takeaway.com/media/press-releases/. Accessed 18 April 2019.

NPD. Foodservice Delivery Among Fastest Growing U.S. Restaurant Industry Trends. https://www.npd.com/wps/portal/npd/us/news/press-releases/2018/foodservice-delivery-in-us-posts-double-digit-gains-over-last-five-years-with-room-to-grow/. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Caspi CE, Sorensen G, Subramanian SV, Kawachi I. The local food environment and diet: a systematic review. Health Place 2012;18:1172–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HEALTHPLACE.2012.05.006.

Cobb LK, Appel LJ, Franco M, Jones-Smith JC, Nur A, Anderson CAM. The relationship of the local food environment with obesity: a systematic review of methods, study quality, and results. Obesity 2015;23:1331–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21118.

Maimaiti M, Ma X, Zhao X, Jia M, Li J, Yang M et al. Multiplicity and complexity of food environment in China: full-scale field census of food outlets in a typical district. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-019-0462-5.

Keeble M, Burgoine T, White M, Summerbell C, Cummins S, Adams J. How does local government use the planning system to regulate hot food takeaway outlets? A census of current practice in England using document review. Health Place 2019;57:171–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.03.010.

Pigatto G, Machado JG, de CF, Negreti A, dos S, Machado LM. Have you chosen your request? Analysis of online food delivery companies in Brazil. Br Food J. 2017;119:639–57. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-05-2016-0207.

Correa JC, Garzón W, Brooker P, Sakarkar G, Carranza SA, Yunado L, et al. Evaluation of collaborative consumption of food delivery services through web mining techniques. J Retail Consum Serv. 2019;46:45–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JRETCONSER.2018.05.002.

Kapoor AP, Vij M. Technology at the dinner table: Ordering food online through mobile apps. J Retail Consum Serv. 2018;43:342–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JRETCONSER.2018.04.001.

Yeo VCS, Goh S-K, Rezaei S. Consumer experiences, attitude and behavioral intention toward online food delivery (OFD) services. J Retail Consum Serv. 2017;35:150–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JRETCONSER.2016.12.013.

Cho M, Bonn MA, Li J. Differences in perceptions about food delivery apps between single-person and multi-person households. Int J Hosp Manag. 2019;77:108–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHM.2018.06.019.

Poelman, MP, Steenhuis IHM. Food choice in Context. 7.5.4 Digital and Online context. In: Herbert L Meiselman, edito. Context: the effects of environment on product design and evaluation. 1st ed. Elsevier; 2019. p. 158–9.

Statistics Netherlands. Begrippen (‘terms’) - buurt (‘neighborhood’). https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/onze-diensten/methoden/begrippen?tab=b#id=buurt. Accessed 14 May 2019.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/2033.0.55.001. Accessed 14 May 2019.

Kimes PLS. Online, mobile, and text food ordering in the U.S. restaurant industry. Cornell Hosp Rep. 2011;11:6–15.

Turrell G, Giskes K. Socio-economic disadvantage and the purchase of takeaway food: A multilevel analysis. Appetite 2008;51:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APPET.2007.12.002.

Kent JL, Thompson S. The three domains of urban planning for health and well-being. J Plan Lit. 2014;29:239–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412214520712.

Caraher M, O’Keefe E, Lloyd S, Madelin T. The planning system and fast food outlets in London: lessons for health promotion practice. Rev Port Saúde Pública. 2013;31:49–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RPSP.2013.01.001.

Muller C. Restaurant delivery: are the “ODP” the Industry’s “OTA”? Part I & II. Boston Hospitality review. 2018. https://www.bu.edu/bhr/files/2018/10/Restaurant-Delivery-Are-the-ODP-the-Industrys-OTA-Part-I-and-II.pdf.

Acknowledgements

We thank Manuela Rigo for collecting the data used in this study. We also thank Jenny Phan for assisting with the neighborhood sampling in Chicago.

Funding

The contribution of the first author (MP) is supported by the Innovational Research Incentives Scheme (#451-16-029), financed by The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). Internal University funding (LT) was used to fund the data collection component of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MP and LT designed the research and analyzed the data, interpret the results, and drafted the paper. SZ contributed to the design of the study and interpretation of the results and critically revised the paper. All authors approved the final version and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Poelman, M.P., Thornton, L. & Zenk, S.N. A cross-sectional comparison of meal delivery options in three international cities. Eur J Clin Nutr 74, 1465–1473 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-020-0630-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-020-0630-7

This article is cited by

-

Response of the consumers to the menu calorie-labeling on online food ordering applications in Saudi Arabia

BMC Nutrition (2024)

-

Nutritional quality and consumer health perception of online delivery food in the context of China

BMC Public Health (2022)

-

Is having a 20-minute neighbourhood associated with eating out behaviours and takeaway home delivery? A cross-sectional analysis of ProjectPLAN

BMC Public Health (2022)

-

Associations between online food outlet access and online food delivery service use amongst adults in the UK: a cross-sectional analysis of linked data

BMC Public Health (2021)