Abstract

Two-photon-pumped dye lasers are very important because of their applications in wavelength up-conversion, optical data storage, biological imaging and photodynamic therapy. Such lasers are very difficult to realize in the solid state because of the aggregation-caused quenching. Here we demonstrate a new two-photon-pumped micro-laser by encapsulating the cationic pyridinium hemicyanine dye into an anionic metal-organic framework (MOF). The resultant MOF⊃dye composite exhibits significant two-photon fluorescence because of the large absorption cross-section and the encapsulation-enhanced luminescent efficiency of the dye. Furthermore, the well-faceted MOF crystal serves as a natural Fabry–Perot resonance cavity, leading to lasing around 640 nm when pumped with a 1064-nm pulse laser. This strategy not only combines the crystalline benefit of MOFs and luminescent behaviour of organic dyes but also creates a new synergistic two-photon-pumped lasing functionality, opening a new avenue for the future creation of solid-state photonic materials and devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have been rapidly developed as a new type of multifunctional luminescent materials1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Such organic–inorganic hybrid luminescence, which can take advantage of both traditional inorganic and organic photoluminescent materials, can provide unique luminescent properties and thus lead to some novel functional materials. In fact, the luminescent properties of MOF materials can not only be generated from the metal ions/clusters and organic linkers (two basic components for MOFs) but can also be tuned by guest molecules/ions and the interplay/interactions among these different components. Rapid progress in this area over the past several years has led to some potentially useful luminescent MOF materials as chemical sensors and light-emitting devices14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22.

Two-photon-excited fluorescence and two-photon-pumped (TPP) lasing are very important because of their diverse applications in optical data storage, optical limiting, biological imaging and photodynamic therapy23,24,25,26,27. Unlike conventional single-photon emission, TPP fluorescence and lasing can be pumped at a much longer excitation wavelength up to the red or near-infrared spectral region. This lower energy excitation requirement enables the implementation of semiconductor diode lasers as pump sources to significantly enhance the photostability of materials. More importantly, TPP lasing does not require stringent phase-matching, which is superior to second harmonic generation (SHG)-based frequency up-conversion. Although TPP lasing behaviours have been demonstrated in some organic dyes such as rhodamine 6 G, rhodamine B, DCM and pyridinium hemicyanine, they can only be realized in dilute solutions23,28,29,30,31. The aggregation-caused quenching, particularly in the solid state, has seriously limited the development of solid-state TPP up-conversion lasers31.

Serving as host matrices, MOFs offer a unique platform to stabilize and confine functional species, leading to specific behaviour inside the defined pore environments. In fact, through the introduction of a variety of metal ions, quantum dots, nanoparticles and fluorescent dyes into their pore spaces, a variety of MOF composites have been realized as novel functional materials for gas storage and optical devices32,33,34,35,36,37. Immobilization of organic dyes into the pore spaces of MOFs can minimize aggregation-caused quenching. Thus, MOF⊃ organic dye composites should be a very promising means of realizing two-photon-excited up-conversion luminescence and TPP dye lasers.

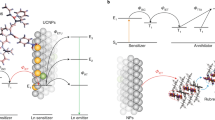

Herein, we report the first TPP micro-laser based on a MOF⊃ organic dye composite in which the cationic pyridinium hemicyanine dye 4-[p-(dimethylamino)styryl]-1-methylpyridinium (DMASM) with a large two-photon absorption (TPA) cross-section was encapsulated within an anionic MOF, bio-MOF-1 (Zn8(Ad)4(BPDC)6O·2Me2NH2, Ad=adeninate; BPDC=biphenyldicarboxylate)38. The bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM composite exhibits significant two-photon-excited fluorescence, with the well-faceted MOF crystal serving as a natural laser resonance cavity, leading to remarkable TPP red lasing when excited with a 1,064-nm near-infrared pulse laser.

Results

Synthesis and characterization

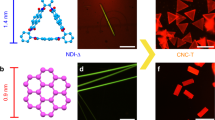

Micrometer-sized single crystals of bio-MOF-1 were synthesized via a solvothermal reaction of zinc acetate dihydrate, biphenyldicarboxylic acid and adenine as described in the literature38. Bio-MOF-1 is a crystalline porous material exhibiting two types of one-dimensional (1D) channels along the c axis of about 7 × 7 and 10 × 10 Å2, respectively (Fig. 1, Supplementary Figs S1 and S2). The channels are occupied by Me2NH2 cations, which allows the introduction of the cationic dye DMASM via an ion-exchange process through a process similar to that described in our previous work37. The content of DMASM dye inside the pores can be systematically controlled by making use of different concentrations of dye solution from 0.34 to 10.92 mM. It should be pointed out that bio-MOF-1 significantly enriches DMASM cations into the pores from the solution (Supplementary Fig. S3), attributed to the energetically favourable interactions between the dye molecules and the MOF scaffold39. Owing to the strong electrostatic interactions between cationic dyes and the anionic framework within bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM, 0.8 mmol cm−3 DMASM cations can be loaded into the pores, indicating that most Me2NH2 cations in the as-synthesized bio-MOF-1 have been replaced by DMASM cations in bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM.

The crystals of as-synthesized bio-MOF-1 exhibit blue emission derived from the BPDC linkers under ultraviolet light excitation of 365 nm (Supplementary Figs S4–S7). As the DMASM cations are gradually incorporated into the pore matrix, the resulting bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM composites display new luminescence emission profiles in the orange to red region (Fig. 2). Such colour changes are mainly because of the combination of emissions attributed to bio-MOF-1 (blue at 410 nm) and dye DMASM (red in the range of 610–640 nm), and the energy transfer from MOF to dye. As the dye concentration gradually increases, the red emission is enhanced while the blue one is gradually quenched, leading to intermediate colours of light magenta, orange and finally red. Furthermore, the energy transfer from bio-MOF-1 to the dye (as shown in Supplementary Fig. S7a, there are spectral overlap between the absorption of dye DMASM and the emission of bio-MOF-1, therefore the energy transfer from bio-MOF-1 to the dye occurs), particularly at high concentrations of the dye, leads to the dominant colour of the dye as red eventually. This unique feature enables in situ visualization of the entry of DMASM molecules into the pores of bio-MOF-1 by fluorescence microscopy.

Figure 3 shows the fluorescence microscopy images of a bio-MOF-1 crystal immersed in DMASMI solution for different periods of time. The end regions of the rod-like crystal generate bright-red emission first, and then the red luminescent regions gradually extend along the longitudinal direction of the crystal. The emission on the external faces may be attributed to the adsorption of trace amount of DMASM cations on the surface, given the fact that the fluorescence microscopy images were recorded on the bio-MOF-1 in DMASMI solution. Finally, the entire MOF crystal displays strong red emission after the as-synthesized bio-MOF-1 is immersed in DMASMI solution for 6 h. This implies that the ion-exchange process occurs through the diffusion of DMASM cations along the 1D channel pores of bio-MOF-1. Such diffusion behaviour was further rationalized by the simulated morphology of bio-MOF-1 using the Bravais–Friedel–Donnay–Harker method. The simulated results (Supplementary Fig. S8) indicate that the c axis direction of bio-MOF-1 corresponds to the longitudinal direction of the rod-like crystal. Apparently, only the 1D channel pores along the c axis allow the DMASM molecules to line up and diffuse into the framework because of the large size of the DMASM molecules. The uniform distribution of DMASM cations in the bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM crystals was confirmed using confocal laser scanning microscopy in both depth scan and lambda scan modes. As shown in Supplementary Figs S9, S10, the bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM crystals have a uniform fluorescence profile at different depths. Furthermore, lambda scanning using confocal microscopy shows that three different regions in the crystal exhibit similar emission spectra, indicating that the DMASM dyes are indeed uniformly distributed throughout bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM.

Enhanced fluorescence in bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM

To establish the confinement effect, the emission profile of a 1.0 × 10−5M DMASMI solution in DMF, a DMASMI powder and bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM with a dye content of 1.2% were examined. As shown in Fig. 4, the DMASMI solution and DMASMI powder display very weak emission at 620 and 636 nm, respectively, whereas the DMASM-included bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM exhibits a much stronger emission at 610 nm. Such a significant emission enhancement is attributed to the pore confinement of DMASMI molecules within bio-MOF-1, which was further confirmed by the large difference in fluorescence quantum efficiency of bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM versus both DMASMI solution and powder. The dye DMASMI exhibits a fluorescence quantum efficiency of 0.45 and 1.48% in DMF solution and solid powder, respectively; however, bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM exhibits a much higher efficiency of 25.87%. We speculate that the cationic DMASM dye molecules confined in the pores of bio-MOF-1 have restricted intramolecular torsional motion and restrained π–π interactions, which significantly diminish the aggregation-caused quenching effect observed in both DMASMI solution and powder40,41,42. As the MOF contains a large amount of highly conjugated organic linkers, we speculate that there also exists π–π interactions between dye molecules and the MOF organic linkers, although no direct evidence can be established. Unlike the π–π interactions within the dye molecules, the π–π interactions between the dye molecules and MOF organic linkers will enhance the quantum yield of observed emission. Under linear polarization excitation, the bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM crystal displays clear anisotropic emission. As shown in Supplementary Figs S11 and S12, the stronger emission was observed under the perpendicular polarized excitation (θ=90°), which means that the DMASM molecules are aligned preferentially and perpendicularly to the longitudinal direction of the MOF crystal. Such directional alignment of the DMASM molecules within the MOF channels is attributed to intermolecular interactions, particularly π–π interactions, between DMASM molecules and the conjugated organic linkers. In addition, SHG measurements indicate that, although both bio-MOF-1 and DMASMI powder do not exhibit any SHG response, bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM displays moderate SHG intensity that is 0.41 times that of α-quartz (Supplementary Fig. S13). The SHG response of bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM further indicates that the dye DMASM molecules are aligned and oriented in the channels of bio-MOF-1 (ref. 37).

TPP fluorescence and lasing

The large TPA cross-section of DMASMI dyes of about 104 GM (GM=10−50cm4s photon−1 per molecule) and the significantly enhanced luminescent efficiency enables the bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM to be an excellent two-photon-excited up-conversion emitter28. Figure 5a shows the single-photon- and two-photon-excited emission spectra of bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM with a dye content of 28%. The bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM shows a strong emission peaked at 637 nm under an excitation wavelength of 532 nm, whereas the emission peak is red-shifted by 15 nm when excited at 1,064 nm, accompanied by the narrowing of the full-width at half-maximum from 50 to 33 nm. The emission peak of bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM from excitation at 532 nm exhibits a 27 nm red-shift compared with the sample shown in Fig. 4, which we attribute to reabsorption effects and/or dye aggregation at higher concentrations43 (Supplementary Figs S14 and S15). In addition, the further red shift of 15 nm under 1,064 nm excitation can also be ascribed to the reabsorption effect23,29. The emission intensity under 1,064 nm excitation shows a quadratic dependence on the pump energy (Supplementary Fig. S16), indicating that a two-photon-excited process does occur.

(a) Single-photon- and two-photon-excited emission spectra of bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM; (b) two-photon-pumped lasing spectra of bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM under different pumped pulse energy. Inset: microscopy image of a bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM single crystal excited at 1,064 nm (left) and power dependence profile of the fluorescence intensity (right).

In order to generate TPP lasing, an isolated single crystal of bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM was placed under a microscope and pumped using a pulse Nd:YAG laser at 1,064 nm at room temperature. The resulting lasing output beam from the crystal was focused and collected using a high-resolution fibre optic spectrometer (Supplementary Fig. S17). The bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM crystal exhibits a strong red light spot of about 50 μm in diameter when focusing near infrared light of 1,064 nm to excite the middle part of the crystal. Figure 5b shows the lasing spectra of a bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM crystal under different pump powers. Under a low pump energy of 0.113 mJ, the emission spectra is dominated by a very weak and broad spontaneous emission. As the pump power increases to 0.172 mJ, a highly structured emission spectrum centred at 640 nm is apparent. The emission intensities are further enhanced when the pump energy is increased to 0.209 mJ. The inset of Fig. 5b illustrates the pump energy dependence of the fluorescence intensity, displaying clearly an energy threshold of about 0.148 mJ. The presence of a threshold energy coupled with the rapid increase in intensity with quadratic pump energy suggests that the TPP-stimulated emission has occurred in the bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM crystal. Compared with the emission peaked at 650 nm under two-photon excitation, the TPP lasing exhibits a 10-nm blue-shift. The possible reason for such a lasing emission at the lower wavelength is not very clear. Several examples have been reported in the literature. We speculate that the mechanism in the present case is similar to one rationalized previously: the amplified spontaneous emission is predominantly emitted before spectral relaxation of the excited states within the inhomogeneous broadened density of states takes place44,45.

Discussion

Generally, laser emission cannot happen without appropriate resonator cavity feedback. Several feedback mechanisms including random resonant effect, Fabry–Perot cavity resonance, distributed feedback and whispering gallery modes have been developed to account for lasing46,47,48,49,50,51,52. In the bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM crystal, the top and bottom facets of a rectangular MOF crystal can act as the mirrors of a Fabry–Perot cavity, thus efficiently reflecting the stimulated emission to provide the necessary feedback for lasing action. On the other hand, the sharp peaks in the PL spectra above the pump threshold also imply that the laser emission can be attributed to a Fabry–Perot cavity mechanism. In order to understand the relationship between the resonance modes and the size of the MOF microcavity, the lasing spectra of three bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM single crystals with thicknesses of 30, 50 and 85 μm were measured, respectively. As shown in Fig. 6, the laser emission presents an increasing number of resonance modes with increasing thickness of the MOF crystal. For a Fabry–Perot mechanism, the difference in peak position Δλ (mode spacing) is given by

where L is the cavity length, corresponding to the thickness of MOF crystal, λ is the light wavelength and ng is the group refractive index53. The measured mode spacing, Δλ, at λ=640 nm demonstrates clearly a linear relationship with 1/L (Supplementary Fig. S18), which agrees well with equation 1. This confirms that the opposing top and bottom faces of the MOF crystals indeed function as two reflectors of a Fabry–Perot cavity and provide strong self-cavity optical confinement and optical feedback. The formation of natural cavities in MOFs suggests a simple chemical approach to achieve a micro-laser without etching and coating. The factor, which is an important parameter to describe laser cavities, is estimated to be about 1,500 according to the definition

where f is the resonant frequency and Δf is the full-width at half-maximum of the resonant frequency, respectively46. The high factor may be attributed to the desirable TPP emission efficiency of bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM and the high crystal quality and photostability (Supplementary Fig. S19) that alleviates optical loss because of scattering.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a new TPP micro-laser based on dye-encapsulated MOF material, bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM. The high luminescent efficiency is attributed to the pore confinement of the porous anionic framework and the large TPA cross-section of the DMASMI dye. These features enable the bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM to generate significant two-photon-excited fluorescence and stimulated emission under excitation with an Nd:YAG laser at 1,064 nm. More importantly, the pair top and bottom faces of the bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM crystal act as reflectors to constitute a high-quality (≈1,500) Fabry–Perot cavity, leading to TPP lasing around 640 nm when pumped under a 1,064-nm pulse laser with a threshold of 0.148 mJ. These results open a new perspective for design of highly efficient TPP micro-lasers for integrated photonic circuits. As this TPP micro-laser can be further miniaturized through the nanoscale processing of MOFs, the dye/MOF composite strategy, which combines the porous and crystalline benefits of MOF matrices with the luminescent behaviour of organic dyes, will enable us to rationally incorporate multiple target chromophores within the MOF matrix to develop new photonic materials and devices in the near future.

Methods

Synthesis of bio-MOF-1

The synthesis method of bio-MOF-1 was carried out according to a literature method with minor modifications38. To a solution of adenine (0.25 mmol) and 4,4′-biphenyl dicarboxylic acid (H2BPDC) (0.375 mmol) in DMF (70 ml), was added dropwise a solution of zinc acetate dihydrate (0.15 mmol) in water (4 ml). A white precipitate formed was dissolved after the addition of nitric acid (0.25 ml), and the resultant solution was heated at 130 °C for 24 h to afford transparent rod-like crystals. Crystals of regular morphology were collected by filtration, washed with DMF and dried in air.

Synthesis of pyridinium hemicyanine dye DMASMI

4-Picoline (9.30 g, 0.10 mol) was dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (200 ml) and stirred vigorously while methyl iodide (56.70 g, 0.40 mmol, 24.9 ml) was added dropwise. The resultant mixture was refluxed for 6 h. After THF and methyl iodide were removed, brown needle-like crystals of 1,4-dimethylpyridinium iodide were obtained and used for the following reaction without further purification54.

To a solution of 4-(N, N-dimethylamino)benzaldehyde (14.95 g, 100 mmol) and 1,4-dimethylpyridinium iodide (23.10 g, 98 mmol) in ethanol (250 ml) was added piperidine (2.00 ml). The yellow solution was refluxed for 1 day and then cooled to room temperature. The resultant precipitate was collected and recrystallized from methanol to yield red needle-like crystals of DMASM iodide (DMASMI, 25.90 g, 72%). Mp: 262 °C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, δ p.p.m.) 8.67 (d, J=6 Hz, 2 H), 8.04 (d, J=6 Hz, 2 H), 7.90 (d, J=16 Hz, 1 H), 7.59 (d, J=8.5 Hz, 2 H), 7.17 (d, J=16 Hz, 1 H), 6.78 (d, J=8.5 Hz, 2 H), 4.17 (s, 3 H), 3.02 (s, 6 H). Calcd. for C16H19IN2 (366.24): C, 52.47; H, 5.23; N, 7.65. Found: C, 52.49; H, 5.28; N, 7.54. (see Supplementary Fig. S20).

Synthesis of bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM

Crystals of bio-MOF-1 were immersed in a solution of DMASMI in DMF with varying concentrations from 0.34 to 10.92 mM at ambient temperature for 4 days to yield a series of bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM MOF/dye composites with different DMASM cation content. The products were washed thoroughly with DMF four times and EtOH twice to remove residual DMASMI on the surface of bio-MOF-1 and dried at 60 °C for 4 h.

Measurements

Fluorescence microscopic images were taken on an Olympus IX 71 inverted fluorescence microscope using a U-MWU2 filter unit (transmittance centre is around 340 nm). An Ideaoptics PG2000 fibre optic spectrometer was used to record the microscopic spectra of crystals immersed in DMASMI solution. Confocal laser scanning images were taken on an Olympus FV 1000 laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with an Olympus IX 81 inverted microscope. A New Wave Q-switched Nd:YAG laser (1,064 nm, pulse duration about 3–5 ns, 10 Hz) was used as the two-photon excitation and pumping source. Diffuse reflective two-photon fluorescence excited by a 1-mm-diameter laser spot was recorded using a high-resolution fibre optic spectrometer (Ideaoptics FX4000). The lasing spectral measurement setup is shown in Supplementary Fig. S17. The incident laser was partially focused on crystals through an objective lens ( × 20, numerical aperture=0.40) with an exposure region of radius around 25 μm and a pulse energy in the range 0.05–0.40 mJ. The excited red light was focused and collected by the fibre optic spectrometer.

Excitation and emission spectra of DMASMI powder, solution in DMF and bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM were taken in a Hitachi F-4600 spectrometer. As the excitation filter of the fluorescent microscope has a transmittance centred around 340 nm, whereas both bio-MOF-1 and bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM exhibit good excitation efficiency in the range of 330–380 nm, especially, bio-MOF-1, which exhibits a maximum excitation wavelength at 365 nm (Supplementary Fig. S7), the emission spectra in our measurements were recorded at excitation wavelengths of 340 or 365 nm. Quantum yield measurements were performed using the absolute method on a FLS920 from Edinburgh Instruments equipped with a BaSO4-coated integrating sphere55, a 450 W Xe900 Xenon lamp and a R928P PMT detector. The samples bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM and DMASMI solution (1.0 × 10−5M) were measured at an excitation wavelength of 468 nm (Supplementary Fig. S21). A 142-mm (inner)-diameter integrating sphere equipped with a cuvette holder and mounts for solid samples and two access ports for the light path was fitted in place of the standard sample holder to collect the excitation and emission light. The absolute quantum yields were calculated by comparing the integral of emission and the absorption of excitation light, with a sensitivity correction for the detector.

Determination of dye contents

Well-dried dye-included crystals of bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM (~10 mg) were soaked in a saturated LiCl/DMF solution to exchange cations with Li+ to yield free dye cations in solution. The concentration and mass of DMASM in solution (mDMASM) were determined using ultraviolet–vis spectroscopy. Assuming the number of replaced cations is n, the chemical formula for dried dye-included compound is Zn8(C5H4N5)4(C14H8O4)6O(C16H19N2)2−n(C16H19N2)n, whose molecular weight is 2,516.78+46.09(2−n)+239.34n. In this compound, the mass content of dye cations is expressed as 242.23n/[2,516.78+46.09(2−n)+239.34n]=mDMASM/mbio-MOF-1⊃DMASM=R, where R is the mass fraction of cationic dye in the bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM composite, determined through the above procedure. In the case of completely dye-exchanged bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM composite, R=0.1598, and thus the value of n can be derived as n=2,608.96 R/(239.34–193.25 R), (R⩽0.1598).

The dye concentration of the bio-MOF-1⊃DMASM composite is calculated from c=nZ/NAV, where Z=4, V=16339.1 Å3 from crystallographic data38 and NA=6.02 × 1023mol−1 is Avogadro’s constant.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Yu, J. et al. Confinement of pyridinium hemicyanine dye within an anionic metal-organic framework for two-photon-pumped lasing. Nat. Commun. 4:2719 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3719 (2013).

References

Zhou, H.-C., Long, J. R. & Yaghi, O. M. Introduction to metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 112, 673–674 (2012).

Long, J. R. & Yaghi, O. M. The pervasive chemistry of metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1213–1214 (2009).

Kitagawa, S., Kitaura, R. & Noro, S. Functional porous coordination polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 2334–2375 (2004).

Kreno, L. E. et al. Metal-organic framework materials as chemical sensors. Chem. Rev. 112, 1105–1125 (2012).

Chen, B., Xiang, S. & Qian, G. Metal-organic frameworks with functional pores for recognition of small molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 43, 1115–1124 (2010).

Cui, Y., Yue, Y., Qian, G. & Chen, B. Luminescent functional metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 112, 1126–1162 (2012).

Rocha, J., Carlos, L. D., Paz, F. A. A. & Ananias, D. Luminescent multifunctional lanthanides-based metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 926–940 (2011).

Allendorf, M. D., Bauer, C. A., Bhakta, R. K. & Houk, R. J. T. Luminescent metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1330–1352 (2009).

Férey, G. et al. Why hybrid porous solids capture greenhouse gases? Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 550 (2011).

Horcajada, P. et al. Metal–organic frameworks in biomedicine. Chem. Rev. 112, 1232–1268 (2012).

Zhang, J.-P., Zhang, Y.-B., Lin, J.-B. & Chen, X.-M. Metal azolate frameworks: from crystal engineering to functional materials. Chem. Rev. 112, 1001–1033 (2012).

Shimizu, G. K. H., Vaidhyanathan, R. & Taylor, J. M. Phosphonate and sulfonate metal organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1430–1449 (2009).

Zheng, S.-T. et al. Development of composite inorganic building blocks for MOFs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 4517–4520 (2012).

Sato, H., Matsuda, R., Sugimoto, K., Takata, M. & Kitagawa, S. Photoactivation of a nanoporous crystal for on-demand guest trapping and conversion. Nat. Mater. 9, 661–666 (2010).

Takashima, Y. et al. Molecular decoding using luminescence from an entangled porous framework. Nat. Commun. 2, 168 (2011).

Cui, Y. et al. A luminescent mixed-lanthanide metal–organic framework thermometer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 3979–3982 (2012).

Chen, B. et al. A luminescent metal-organic framework with lewis basic pyridyl sites for the sensing of metal ions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 500–503 (2009).

Chen, B., Wang, L., Zapata, F., Qian, G. & Lobkovsky, E. B. A luminescent microporous metal-organic framework for the recognition and sensing of anions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 6718–6719 (2008).

Chen, B. et al. Luminescent open metal sites within a metal-organic framework for sensing small molecules. Adv. Mater. 19, 1693–1696 (2007).

Stylianou, K. C. et al. A guest-responsive fluorescent 3D microporous metal-organic framework derived from a long-lifetime pyrene core. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 4119–4130 (2010).

Jiang, H.-L., Tatsu, Y., Lu, Z.-H. & Xu, Q. Non-, micro-, and mesoporous metal−organic framework isomers: reversible transformation, fluorescence sensing, and large molecule separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 5586–5587 (2010).

Chandler, B. D., Cramb, D. T. & Shimizu, G. K. H. Microporous metal-organic frameworks formed in a stepwise manner from luminescent building blocks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 10403–10412 (2006).

He, G. S., Tan, L. S., Zheng, Q. & Prasad, P. N. Multiphoton absorbing materials: molecular designs, characterizations, and applications. Chem. Rev. 108, 1245–1330 (2008).

Zhang, C. et al. Two-photon pumped lasing in single-crystal organic nanowire exciton polariton resonators. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 7276–7279 (2011).

Li, L., Ge, J., Wu, H., Xu, Q. H. & Yao, S. Q. Organelle-specific detection of phosphatase activities with two-photon fluorogenic probes in cells and tissues. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 12157–12167 (2012).

Xing, G. et al. Ultralow-threshold two-photon pumped amplified spontaneous emission and lasing from seeded CdSe/CdS nanorod heterostructures. ACS Nano 6, 10835–10844 (2012).

Fan, H. H., Guo, L., Li, K. F., Wong, M. S. & Cheah, K. W. Exceptionally strong multiphoton-excited blue photoluminescence and lasing from ladder-type oligo(p-phenylene)s. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 7297–7300 (2012).

Zhao, C. F., He, G. S., Bhawalkar, J. D., Park, C. K. & Prasad, P. N. Newly synthesized dyes and their polymer/glass composites for one- and two-photon pumped solid-state cavity lasing. Chem. Mater. 7, 1979–1983 (1995).

Ren, Y. et al. Synthesis, structures and two-photon pumped up-conversion lasing properties of two new organic salts. J. Mater. Chem. 10, 2025–2030 (2000).

Zheng, M.-L., Fujita, K., Chen, W.-Q., Duan, X.-M. & Kawata, S. Two-photon excited fluorescence and second-harmonic generation of the DAST organic nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 8988–8993 (2011).

Fang, H.-H. et al. Two-photon pumped amplified spontaneous emission from cyano-substituted oligo(p-phenylenevinylene) crystals with aggregation-induced emission enhancement. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 11958–11961 (2010).

Ma, L., Falkowski, J. M., Abney, C. & Lin, W. A series of isoreticular chiral metal-organic frameworks as a tunable platform for asymmetric catalysis. Nat. Chem. 2, 838–846 (2010).

Yanai, N. et al. Gas detection by structural variations of fluorescent guest molecules in a flexible porous coordination polymer. Nat. Mater. 10, 787–793 (2011).

Lu, G. et al. Imparting functionality to a metal-organic framework material by controlled nanoparticle encapsulation. Nat. Chem. 4, 310–316 (2012).

Yang, S. et al. Cation-induced kinetic trapping and enhanced hydrogen adsorption in a modulated anionic metal-organic framework. Nat. Chem. 1, 487–493 (2009).

Wang, C., deKrafft, K. E. & Lin, W. Pt nanoparticles@photoactive metal-organic frameworks: efficient hydrogen evolution via synergistic photo-excitation and electron injection. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 7211–7214 (2012).

Yu, J. et al. Second-order nonlinear optical activity induced by ordered dipolar chromophores confined in the pores of an anionic metal-organic framework. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 10542–10545 (2012).

An, J., Geib, S. J. & Rosi, N. L. Cation-triggered drug release from a porous zinc-adeninate metal-organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 8376–8377 (2009).

Han, S., Hermans, T. M., Fuller, P. E., Wei, Y. & Grzybowski, B. A. Transport into metal-organic frameworks from solution is not purely diffusive. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 2662–2666 (2012).

Hong, Y., Lam, J. W. & Tang, B. Z. Aggregation-induced emission. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 5361–5388 (2011).

Dong, Y. et al. Switching the light emission of (4-biphenylyl)phenyldibenzofulvene by morphological modulation: crystallization-induced emission enhancement. Chem. Commun. 43, 40–42 (2007).

Shustova, N. B., McCarthy, B. D. & Dinca, M. Turn-on fluorescence in tetraphenylethylene-based metal-organic frameworks: an alternative to aggregation-induced emission. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 20126–20129 (2011).

Smiley, S. T. et al. Intracellular heterogeneity in mitochondrial membrane potentials revealed by a J-aggregate-forming lipophilic cation JC-1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 88, 3671–3675 (1991).

Vehse, M., Liu, B., Edman, L., Bazan, G. C. & Heeger, A. J. Light amplification by optical excitation of a chemical defect in a conjugated polymer. Adv. Mater. 16, 1001–1004 (2004).

Jin, F., Song, Y., Dong, X.-Z., Chen, W.-Q. & Duan, X.-M. Amplified spontaneous emission from dye-doped polymer film sandwiched by two opal photonic crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 031109–031103 (2007).

Chen, R., Van Duong, T. & Sun, H. D. Single mode lasing from hybrid hemispherical microresonators. Sci. Rep. 2, 244 (2012).

Bruhwiler, D. et al. Nanochannels for supramolecular organization of luminescent guests. J. Mater. Chem. 19, 8040–8067 (2009).

Calzaferri, G., Huber, S., Maas, H. & Minkowski, C. Host–guest antenna materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 3732–3758 (2003).

Calzaferri, G. et al. Photonic antenna system for light harvesting, transport and trapping. J. Mater. Chem. 12, 1–13 (2002).

Calzaferri, G., Li, H. & Brühwiler, D. Dye-modified nanochannel materials for photoelectronic and optical devices. Chem. Eur. J. 14, 7442–7449 (2008).

Vietze, U. et al. Zeolite-dye microlasers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 4628–4631 (1998).

Weiß, Ö. et al. Host-guest-systems Based on Nanoporous Crystals 544–557Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA (2005).

Xu, Z. et al. Low-threshold nanolasers based on slab-nanocrystals of H-aggregated organic semiconductors. Adv. Mater. 24, OP216–OP220 (2012).

Okada, S. et al. Synthesis and crystal structure of a novel organic ion-complex crystal for second-order nonlinear optics. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 29, 1112–1115 (1990).

Würth, C., Grabolle, M., Pauli, J., Spieles, M. & Resch-Genger, U. Relative and absolute determination of fluorescence quantum yields of transparent samples. Nat. Protocols 8, 1535–1550 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 51010002, 51272229, 51272231 and 51229201), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. LR13E020001) and the Welch Foundation AX-1730 (BC). We thank the reviewers for their very constructive comments, which have significantly improved the quality of our work. We also thank Dr. Zachary J. Tonzetich for proof-reading the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y., Y.C. and G.Q. conceived and designed the experiments; J.Y. synthesized the MOF materials and performed their characterization; H.X. performed luminescent spectroscopy measurement; Y.Y. and Z.W. designed and carried out the lasing experiments; J.Y., Y.C., B.C. and G.Q. analysed the data and co-wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S21 (PDF 1590 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, J., Cui, Y., Xu, H. et al. Confinement of pyridinium hemicyanine dye within an anionic metal-organic framework for two-photon-pumped lasing. Nat Commun 4, 2719 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3719

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3719

This article is cited by

-

Preparation and quantitative analysis of multicenter luminescence materials for sensing function

Nature Protocols (2023)

-

Low-dimensional assemblies of metal-organic framework particles and mutually coordinated anisotropy

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Specific sensing of antibiotics with metal-organic frameworks based dual sensor system

Nano Research (2022)

-

Tunable nonlinear optical responses based on host-guest MOF hybrid materials

Science China Materials (2021)

-

Let the light be a guide: Chromophore communication in metal-organic frameworks

Nano Research (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.