Key Points

-

Complement activation can occur through three established pathways: classical, alternative and lectin, resulting in the cleavage of C3 and C5 to generate anaphylatoxin peptides (C3a and C5a) and C3b and C5b. C3b is a major phagocytosis-promoting product, whereas C5b interacts with C6–C9 to form the membrane-attack complex on cell membranes.

-

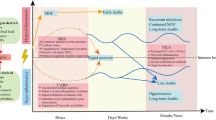

There is clear evidence of complement activation in sepsis, including increased serum levels of C3a, C5a and the soluble C5b–C9 complex. In addition, blood neutrophils show loss of C5a receptor (C5aR), reduced in vitro binding of C5a and loss of chemotactic responsiveness to C5a.

-

C5a, under normal circumstances and under conditions of regulated production, provides defensive functions by enhancing chemotactic responses of neutrophils, phagocytosis and the respiratory burst (production of H2O2) that is involved in killing bacteria.

-

During experimental sepsis, excessive production of C5a results in a series of harmful consequences: defective mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling in neutrophils and loss of chemotactic and phagocytic function, loss of the ability to contain bacteria in the tissues and the blood, and death.

-

In rodents with sepsis, blocking strategies directed against complement include blockade of C5a, blockade of C5aR or blockade of interleukin-6 (which upregulates C5aR). However, these strategies have not yet been successfully translated in human trials, possibly owing to the inability of rodent models to adequately recreate the events that occur in human sepsis.

Abstract

Sepsis is a major clinical problem for which therapeutic interventions have been largely unsuccessful, in spite of promising strategies that were successful in animals, especially rodents. There is new evidence that sepsis causes excessive activation of the complement system and that this induces paralysis of innate immune functions in phagocytic cells due to effects of the powerful complement-activation product, C5a. This review describes our present understanding of how and why sepsis is a life-threatening condition and how it might be more effectively treated.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bone, R. C., Sprung, C. L. & Sibbald, W. J. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure. Crit. Care Med. 20, 724–726 (1992).

Bone, R. C. et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest 101, 1644–1655 (1992).

Levy, M. M. et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International sepsis definitions conference. Crit. Care Med. 31, 1250–1256 (2003). References 1–3 describe the clinical classifications for patients with sepsis.

Sarnak, M. J. & Jaber, B. L. Mortality caused by sepsis in patients with end-stage renal disease compared with the general population. Kidney Int. 58, 1758–1764 (2000).

Waage, A., Halstensen, A. & Espevik, T. Association between tumour necrosis factor in serum and fatal outcome in patients with meningococcal disease. Lancet 1, 355–357 (1987).

Marty, C. et al. Circulating interleukin-8 concentrations in patients with multiple organ failure of septic and nonseptic origin. Crit. Care Med. 22, 673–679 (1994).

Cannon, J. G. et al. Circulating interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor in septic shock and experimental endotoxin fever. J. Infect. Dis. 161, 79–84 (1990).

Pinsky, M. R. et al. Serum cytokine levels in human septic shock. Relation to multiple-system organ failure and mortality. Chest 103, 565–575 (1993).

Vincent, J. L., Sun, Q. & Dubois, M. J. Clinical trials of immunomodulatory therapies in severe sepsis and septic shock. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34, 1084–1093 (2002).

Riedemann, N. C., Guo, R. F. & Ward, P. A. Novel strategies for the treatment of sepsis. Nature Med. 9, 517–524 (2003).

Laudes, I. J. et al. Anti-c5a ameliorates coagulation/fibrinolytic protein changes in a rat model of sepsis. Am. J. Pathol. 160, 1867–1875 (2002).

Guo, R. F. et al. Protective effects of anti-C5a in sepsis-induced thymocyte apoptosis. J. Clin. Invest. 106, 1271–1280 (2000).

Haviland, D. L. et al. Cellular expression of the C5a anaphylatoxin receptor (C5aR): demonstration of C5aR on nonmyeloid cells of the liver and lung. J. Immunol. 154, 1861–1869 (1995).

Monsinjon, T. et al. Regulation by complement C3a and C5a anaphylatoxins of cytokine production in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. FASEB J. 17, 1003–1014 (2003).

Schraufstatter, I. U., Trieu, K., Sikora, L., Sriramarao, P. & DiScipio, R. Complement c3a and c5a induce different signal transduction cascades in endothelial cells. J. Immunol. 169, 2102–2110 (2002).

Riedemann, N. C. et al. Expression and function of the C5a receptor in rat alveolar epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 168, 1919–1925 (2002).

Laudes, I. J. et al. Expression and function of C5a receptor in mouse microvascular endothelial cells. J. Immunol. 169, 5962–5970 (2002).

Schellenberg, R. R. & Foster, A. In vitro responses of human asthmatic airway and pulmonary vascular smooth muscle. Int. Arch. Allergy Appl. Immunol. 75, 237–241 (1984).

del Balzo, U., Polley, M. J. & Levi, R. C3a-induced contraction of guinea pig ileum consists of two components: fast histamine-mediated and slow prostanoid-mediated. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 248, 1003–1009 (1989).

Erdei, A., Kerekes, K. & Pecht, I. Role of C3a and C5a in the activation of mast cells. Exp. Clin. Immunogenet. 14, 16–18 (1997).

Schlesinger, L. S., Bellinger-Kawahara, C. G., Payne, N. R. & Horwitz, M. A. Phagocytosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is mediated by human monocyte complement receptors and complement component C3. J. Immunol. 144, 2771–2780 (1990).

Payne, N. R. & Horwitz, M. A. Phagocytosis of Legionella pneumophila is mediated by human monocyte complement receptors. J. Exp. Med. 166, 1377–1389 (1987).

Pryzwansky, K. B., Lambris, J. D., MacRae, E. K. & Schwab, J. H. Opsonized streptococcal cell walls crosslink human leukocytes and erythrocytes by complement receptors. Infect. Immun. 49, 550–556 (1985).

Vogt, W., Zimmermann, B., Hesse, D. & Nolte, R. Activation of the fifth component of human complement, C5, without cleavage, by methionine oxidizing agents. Mol. Immunol. 29, 251–256 (1992).

Kilgore, K. S., Flory, C. M., Miller, B. F., Evans, V. M. & Warren, J. S. The membrane attack complex of complement induces interleukin-8 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 secretion from human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Am. J. Pathol. 149, 953–961 (1996).

Vogel, C. W. & Muller-Eberhard, H. J. The cobra complement system: I. The alternative pathway of activation. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 9, 311–325 (1985).

Wessels, M. R. et al. Studies of group B streptococcal infection in mice deficient in complement component C3 or C4 demonstrate an essential role for complement in both innate and acquired immunity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 11490–11494 (1995).

Fischer, M. B. et al. Increased susceptibility to endotoxin shock in complement C3- and C4-deficient mice is corrected by C1 inhibitor replacement. J. Immunol. 159, 976–982 (1997).

Sylvestre, D. et al. Immunoglobulin G-mediated inflammatory responses develop normally in complement-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 184, 2385–2392 (1996).

Larsen, G. L., Mitchell, B. C. & Henson, P. M. The pulmonary response of C5 sufficient and deficient mice to immune complexes. Am. Rev. Respir Dis. 123, 434–439 (1981).

Clynes, R. et al. Modulation of immune complex-induced inflammation in vivo by the coordinate expression of activation and inhibitory Fc receptors. J. Exp. Med. 189, 179–185 (1999).

Barrington, R., Zhang, M., Fischer, M. & Carroll, M. C. The role of complement in inflammation and adaptive immunity. Immunol. Rev. 180, 5–15 (2001).

Stahl, G. L. et al. Role for the alternative complement pathway in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Am. J. Pathol. 162, 449–455 (2003).

Frank, M. M. Complement deficiencies. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 47, 1339–1354 (2000). This is a comprehensive review of complement deficiencies.

Trouw, L. A., Seelen, M. A. & Daha, M. R. Complement and renal disease. Mol. Immunol. 40, 125–134 (2003).

Shin, H. S., Snyderman, R., Friedman, E., Mellors, A. & Mayer, M. M. Chemotactic and anaphylatoxic fragment cleaved from the fifth component of guinea pig complement. Science 162, 361–363 (1968).

Chenoweth, D. E. & Hugli, T. E. Demonstration of specific C5a receptor on intact human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 75, 3943–3947 (1978).

van Epps, D. E. & Chenoweth, D. E. Analysis of the binding of fluorescent C5a and C3a to human peripheral blood leukocytes. J. Immunol. 132, 2862–2867 (1984).

Gerard, N. P. & Gerard, C. The chemotactic receptor for human C5a anaphylatoxin. Nature 349, 614–617 (1991).

Huber-Lang, M. S. et al. Structure-function relationships of human C5a and C5aR. J. Immunol. 170, 6115–6124 (2003).

Chen, Z. et al. Residues 21–30 within the extracellular N-terminal region of the C5a receptor represent a binding domain for the C5a anaphylatoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 10411–10419 (1998).

Siciliano, S. J. et al. Two-site binding of C5a by its receptor: an alternative binding paradigm for G protein-coupled receptors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 91, 1214–1218 (1994).

Raffetseder, U. et al. Site-directed mutagenesis of conserved charged residues in the helical region of the human C5a receptor. Arg2O6 determines high-affinity binding sites of C5a receptor. Eur. J. Biochem. 235, 82–90 (1996).

Kola, A. et al. Epitope mapping of a C5a neutralizing mAb using a combined approach of phage display, synthetic peptides and site-directed mutagenesis. Immunotechnology 2, 115–126 (1996).

Chao, T. H. et al. Role of the second extracellular loop of human C3a receptor in agonist binding and receptor function. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 9721–9728 (1999).

Huber-Lang, M. S. et al. Complement-induced impairment of innate immunity during sepsis. J. Immunol. 169, 3223–3231 (2002). This report describes the signalling defects that are acquired in blood neutrophils during caecal ligation and puncture (CLP)-induced sepsis.

Zaitsu, M. et al. New induction of leukotriene A4 hydrolase by interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Blood 96, 601–609 (2000).

Pompeia, C., Cury-Boaventura, M. F. & Curi, R. Arachidonic acid triggers an oxidative burst in leukocytes. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 36, 1549–1560 (2003).

Marder, S. R., Chenoweth, D. E., Goldstein, I. M. & Perez, H. D. Chemotactic responses of human peripheral blood monocytes to the complement-derived peptides C5a and C5a des Arg. J. Immunol. 134, 3325–3331 (1985).

Schumacher, W. A., Fantone, J. C., Kunkel, S. E., Webb, R. C. & Lucchesi, B. R. The anaphylatoxins C3a and C5a are vasodilators in the canine coronary vasculature in vitro and in vivo. Agents Actions 34, 345–349 (1991).

Goldstein, I. M. & Weissmann, G. Generation of C5-derived lysosomal enzyme-releasing activity (C5a) by lysates of leukocyte lysosomes. J. Immunol. 113, 1583–1588 (1974).

Mollnes, T. E. et al. Essential role of the C5a receptor in E. coli-induced oxidative burst and phagocytosis revealed by a novel lepirudin-based human whole blood model of inflammation. Blood 100, 1869–1877 (2002).

Sacks, T., Moldow, C. F., Craddock, P. R., Bowers, T. K. & Jacob, H. S. Oxygen radicals mediate endothelial cell damage by complement-stimulated granulocytes. An in vitro model of immune vascular damage. J. Clin. Invest. 61, 1161–1167 (1978).

Perianayagam, M. C., Balakrishnan, V. S., King, A. J., Pereira, B. J. & Jaber, B. L. C5a delays apoptosis of human neutrophils by a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-signaling pathway. Kidney Int. 61, 456–463 (2002).

Jagels, M. A., Daffern, P. J. & Hugli, T. E. C3a and C5a enhance granulocyte adhesion to endothelial and epithelial cell monolayers: epithelial and endothelial priming is required for C3a-induced eosinophil adhesion. Immunopharmacology 46, 209–222 (2000).

Molad, Y., Haines, K. A., Anderson, D. C., Buyon, J. P. & Cronstein, B. N. Immunocomplexes stimulate different signalling events to chemoattractants in the neutrophil and regulate L-selectin and β2-integrin expression differently. Biochem. J. 299, 881–887 (1994).

Foreman, K. E. et al. C5a-induced expression of P-selectin in endothelial cells. J. Clin. Invest. 94, 1147–1155 (1994).

Hopken, U. et al. Inhibition of interleukin-6 synthesis in an animal model of septic shock by anti-C5a monoclonal antibodies. Eur. J. Immunol. 26, 1103–1109 (1996).

Strieter, R. M. et al. Cytokine-induced neutrophil-derived interleukin-8. Am. J. Pathol. 141, 397–407 (1992).

Younger, J. G. et al. Systemic and lung physiological changes in rats after intravascular activation of complement. J. Appl. Physiol. 90, 2289–2295 (2001).

Hangen, D. H. et al. Complement levels in septic primates treated with anti-C5a antibodies. J. Surg. Res. 46, 195–199 (1989).

Stevens, J. H. et al. Effects of anti-C5a antibodies on the adult respiratory distress syndrome in septic primates. J. Clin. Invest. 77, 1812–1816 (1986).

Smedegard, G., Cui, L. X. & Hugli, T. E. Endotoxin-induced shock in the rat. A role for C5a. Am. J. Pathol. 135, 489–497 (1989).

Czermak, B. J. et al. Protective effects of C5a blockade in sepsis. Nature Med. 5, 788–792 (1999). This was the first paper to establish the protective effects of C5a-specific antibody in CLP-induced sepsis.

Huber-Lang, M. et al. Role of C5a in multiorgan failure during sepsis. J. Immunol. 166, 1193–1199 (2001).

Brandtzaeg, P., Mollnes, T. E. & Kierulf, P. Complement activation and endotoxin levels in systemic meningococcal disease. J. Infect. Dis. 160, 58–65 (1989).

Gardinali, M. et al. Complement activation and polymorphonuclear neutrophil leukocyte elastase in sepsis. Correlation with severity of disease. Arch. Surg. 127, 1219–1224 (1992).

Stove, S. et al. Circulating complement proteins in patients with sepsis or systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 3, 175–183 (1996).

Gerard, C. Complement C5a in the sepsis syndrome — too much of a good thing? N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 167–169 (2003). References 66–70 describe evidence for the generation of complement-activation products during sepsis.

Solomkin, J. S., Jenkins, M. K., Nelson, R. D., Chenoweth, D. & Simmons, R. L. Neutrophil dysfunction in sepsis. II. Evidence for the role of complement activation products in cellular deactivation. Surgery 90, 319–327 (1981).

Tomhave, E. D. et al. Cross-desensitization of receptors for peptide chemoattractants. Characterization of a new form of leukocyte regulation. J. Immunol. 153, 3267–3275 (1994).

Guo, R. F. et al. Neutrophil C5a receptor and the outcome in a rat model of sepsis. FASEB J. 17, 1889–1891 (2003).

Seely, A. J. et al. Alteration of chemoattractant receptor expression regulates human neutrophil chemotaxis in vivo. Ann. Surg. 235, 550–559 (2002).

Riedemann, N. C. et al. Regulation by C5a of neutrophil activation during sepsis. Immunity 19, 193–202 (2003).

Ikeda, K. et al. C5a induces tissue factor activity on endothelial cells. Thromb. Haemost. 77, 394–398 (1997).

Muhlfelder, T. W. et al. C5 chemotactic fragment induces leukocyte production of tissue factor activity: a link between complement and coagulation. J. Clin. Invest. 63, 147–150 (1979).

Carson, S. D. & Johnson, D. R. Consecutive enzyme cascades: complement activation at the cell surface triggers increased tissue factor activity. Blood 76, 361–367 (1990).

Aird, W. C. The role of the endothelium in severe sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Blood 101, 3765–3777 (2003).

Hotchkiss, R. S. et al. Sepsis-induced apoptosis causes progressive profound depletion of B and CD4+ T lymphocytes in humans. J. Immunol. 166, 6952–6963 (2001).

Hotchkiss, R. S. et al. Caspase inhibitors improve survival in sepsis: a critical role of the lymphocyte. Nature Immunol. 1, 496–501 (2000). References 79 and 80 describe the protective effects of caspase blockade in CLP-induced sepsis in mice, apparently by preserving the immune system.

Riedemann, N. C. et al. C5a receptor and thymocyte apoptosis in sepsis. FASEB J. 16, 887–888 (2002).

Riedemann, N. C. et al. Increased C5a receptor expression in sepsis. J. Clin. Invest. 110, 101–108 (2002).

Riedemann, N. C. et al. Protective effects of IL-6 blockade in sepsis are linked to reduced C5a receptor expression. J. Immunol. 170, 503–507 (2003).

Banks, R. E. et al. The acute phase protein response in patients receiving subcutaneous IL-6. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 102, 217–223 (1995).

Bernard, G. R. et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 699–709 (2001).

Huber-Lang, M. S. et al. Protection of innate immunity by C5aR antagonist in septic mice. FASEB J. 16, 1567–1574 (2002).

Short, A. et al. Effects of a new C5a receptor antagonist on C5a- and endotoxin-induced neutropenia in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 126, 551–554 (1999).

Bustin, M. Regulation of DNA-dependent activities by the functional motifs of the high-mobility-group chromosomal proteins. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 5237–5246 (1999).

Andersson, U. et al. High mobility group 1 protein (HMG-1) stimulates proinflammatory cytokine synthesis in human monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 192, 565–570 (2000).

Fiuza, C. et al. Inflammation-promoting activity of HMGB1 on human microvascular endothelial cells. Blood 101, 2652–2660 (2003).

Wang, H. et al. HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science 285, 248–251 (1999).

Nishihira, J. et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF): its potential role in tumor growth and tumor-associated angiogenesis. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 995, 171–182 (2003).

Gando, S. et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor is a critical mediator of systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 27, 1187–1193 (2001).

Calandra, T. et al. Protection from septic shock by neutralization of macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Nature Med. 6, 164–170 (2000).

Beutler, B., Milsark, I. W. & Cerami, A. C. Passive immunization against cachectin/tumor necrosis factor protects mice from lethal effect of endotoxin. Science 229, 869–871 (1985).

Tracey, K. J. et al. Anti-cachectin/TNF monoclonal antibodies prevent septic shock during lethal bacteraemia. Nature 330, 662–664 (1987).

Hamilton, G., Hofbauer, S. & Hamilton, B. Endotoxin, TNF-α, interleukin-6 and parameters of the cellular immune system in patients with intraabdominal sepsis. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 24, 361–368 (1992).

Vogt, W. Cleavage of the fifth component of complement and generation of a functionally active C5b6-like complex by human leukocyte elastase. Immunobiology 201, 470–477 (2000).

Huber-Lang, M. et al. Generation of C5a by phagocytic cells. Am. J. Pathol 161, 1849–1859 (2002).

Amatruda, T. T., Steele, D. A., Slepak, V. Z. & Simon, M. I. Gα16, a G protein α subunit specifically expressed in hematopoietic cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 88, 5587–5591 (1991).

Jiang, H. et al. Pertussis toxin-sensitive activation of phospholipase C by the C5a and fMet-Leu-Phe receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 13430–13434 (1996).

Buhl, A. M., Osawa, S. & Johnson, G. L. Mitogen-activated protein kinase activation requires two signal inputs from the human anaphylatoxin C5a receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 19828–19832 (1995).

Wu, D., Huang, C. K. & Jiang, H. Roles of phospholipid signaling in chemoattractant-induced responses. J. Cell. Sci. 113, 2935–2940 (2000).

Reinhart, K. & Karzai, W. Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in sepsis: update on clinical trials and lessons learned. Crit. Care Med. 29, S121–125 (2001).

Cohen, J. Adjunctive therapy in sepsis: a critical analysis of the clinical trial programme. Br. Med. Bull. 55, 212–225 (1999).

Liu, D. et al. C1 inhibitor prevents endotoxin shock via a direct interaction with lipopolysaccharide. J. Immunol. 171, 2594–2601 (2003).

Fisher, C. J., Jr et al. Recombinant human interleukin 1 receptor antagonist in the treatment of patients with sepsis syndrome. Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Phase III rhIL-1ra Sepsis Syndrome Study Group. JAMA 271, 1836–1843 (1994).

Opal, S. M. et al. Confirmatory interleukin-1 receptor antagonist trial in severe sepsis: a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. The Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist Sepsis Investigator Group. Crit. Care Med. 25, 1115–1124 (1997).

Dhainaut, J. F. et al. Platelet-activating factor receptor antagonist BN 52021 in the treatment of severe sepsis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trial. BN 52021 Sepsis Study Group. Crit. Care Med. 22, 1720–1728 (1994).

Dhainaut, J. F. et al. Confirmatory platelet-activating factor receptor antagonist trial in patients with severe gram-negative bacterial sepsis: a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. BN 52021 Sepsis Investigator Group. Crit. Care Med. 26, 1963–1971 (1998).

Vincent, J. L. et al. A multi-centre, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of liposomal prostaglandin E1 (TLC C-53) in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 27, 1578–1583 (2001).

Yu, M. & Tomasa, G. A double-blind, prospective, randomized trial of ketoconazole, a thromboxane synthetase inhibitor, in the prophylaxis of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Crit. Care Med. 21, 1635–1642 (1993).

Spies, C. D. et al. Influence of N-acetylcysteine on indirect indicators of tissue oxygenation in septic shock patients: results from a prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Crit. Care Med. 22, 1738–1746 (1994).

Avontuur, J. A., Tutein Nolthenius, R. P., van Bodegom, J. W. & Bruining, H. A. Prolonged inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis in severe septic shock: a clinical study. Crit. Care Med. 26, 660–667 (1998).

Warren, B. L. et al. Caring for the critically ill patient. High-dose antithrombin III in severe sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 286, 1869–1878 (2001).

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to R.-F. Guo for his assistance in preparation of the manuscript. Research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Glossary

- SEPSIS

-

The most recent definition of sepsis involves a body temperature >38.3°C or <36°C, heart rate >90 beats/minute, blood leukocyte count >12 × 109/litre, and evidence of bacterial infection but not necessarily bacteraemia. The range of classifications of sepsis include: systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), severe sepsis, septic shock and multi-organ failure.

- BROAD-SPECTRUM ANTIBIOTICS

-

Drugs that kill a wide variety of bacteria or cause cessation of bacterial growth.

- ANAPHYLATOXINS

-

Glycosylated peptides, C3a and C5a, generated during activation of the complement system, with molecular weights of ∼8,000 kDa. These peptides interact with rhodopsin-type receptors (C3a receptor and C5a receptor) on various cell types and induce features of acute inflammation, such as increased blood flow, oedema and smooth-muscle contraction.

- CAECAL LIGATION AND PUNCTURE

-

(CLP). CLP involves ligation of the caecum in rats or mice followed by needle-induced perforation. This induces a state of sepsis with peritonitis and growth of intestine-derived bacteria in the peritoneal cavity, followed by presence of bacteria in the blood and various organs (for example, the liver, lungs and kidneys). The presence of mixed bacteria species (aerobic and anaerobic) is referred to as polymicrobial sepsis.

- ISCHAEMIA-REPERFUSION INJURY

-

Partial or complete cessation of blood flow to an organ or tissue (ischaemia), followed by re-establishment of blood flow (reperfusion). The result is injury, which might be reversible or irreversible, depending on duration of ischaemia and the organ involved.

- RHODOPSIN-TYPE RECEPTOR

-

A seven transmembrane-spanning structure in the cell membrane of a receptor with a cytoplasmic peptide linkage to G-proteins. When a ligand (agonist) interacts with the outer regions of the receptor, intracellular signalling occurs.

- WEIBLE-PALADE GRANULES

-

Cytoplasmic granules in endothelial cells that contain the adhesion molecule, P-selectin, and the clotting factor, von-Willebrand factor (vWF). When endothelial cells are exposed to C5a or stimuli such as histamine, these granules fuse with the cell membrane, causing cell-surface expression of P-selectin and secretion of vWF.

- MULTI-ORGAN FAILURE

-

Evidence of functional failure of numerous organs (for example, the liver, lungs and kidneys) during sepsis or shock, or both.

- CYTOKINE/CHEMOKINE STORM

-

The presence of numerous cytokines (such as tumour-necrosis factor and interleukin-1, IL-1) and chemokines (such as IL-8 and CC-chemokine ligand 2) in the serum during sepsis. This has also been referred to as the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).

- CONSUMPTIVE COAGULOPATHY

-

A reduction in the levels of clotting factors in the plasma as a result of the depletion of these proteins through excessive activation of the clotting system. Under such conditions, the plasma often contains activated clotting factors and complexes (such as thrombin–anti-thrombin), indicating marked activation of the clotting system.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ward, P. The dark side of C5a in sepsis. Nat Rev Immunol 4, 133–142 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/nri1269

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nri1269

This article is cited by

-

Dual inhibition of complement C5 and CD14 attenuates inflammation in a cord blood model

Pediatric Research (2023)

-

The complement system in pediatric acute kidney injury

Pediatric Nephrology (2023)

-

Salvianolic acid A alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation by inhibiting complement activation

BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies (2022)

-

Sepsis-induced immunosuppression: mechanisms, diagnosis and current treatment options

Military Medical Research (2022)

-

Crosstalk between the renin–angiotensin, complement and kallikrein–kinin systems in inflammation

Nature Reviews Immunology (2022)