Abstract

Jupiter's X-ray aurora has been thought to be excited by energetic sulphur and oxygen ions precipitating from the inner magnetosphere into the planet's polar regions1,2,3. Here we report high-spatial-resolution observations that demonstrate that most of Jupiter's northern auroral X-rays come from a ‘hot spot’ located significantly poleward of the latitudes connected to the inner magnetosphere. The hot spot seems to be fixed in magnetic latitude and longitude and occurs in a region where anomalous infrared4,5,6,7 and ultraviolet8 emissions have also been observed. We infer from the data that the particles that excite the aurora originate in the outer magnetosphere. The hot spot X-rays pulsate with an approximately 45-min period, a period similar to that reported for high-latitude radio and energetic electron bursts observed by near-Jupiter spacecraft9,10. These results invalidate the idea that jovian auroral X-ray emissions are mainly excited by steady precipitation of energetic heavy ions from the inner magnetosphere. Instead, the X-rays seem to result from currently unexplained processes in the outer magnetosphere that produce highly localized and highly variable emissions over an extremely wide range of wavelengths.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

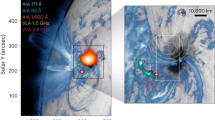

Observations were made with the high-resolution camera (HRC) of the Chandra X-ray Observatory on 18 December 2000 for an entire 10-h Jupiter rotation (from 10–20 UT) in support of the Cassini fly-by of Jupiter. These observations show strong auroral emissions from high latitudes (Fig. 1) as well as a rather featureless disk that probably results from a combination of reflected and fluoresced solar X-rays11. The Chandra data are time-tagged and thus can be mapped into jovian latitude and system III longitude coordinates (system III longitudes are based on the 9.925-hour rotation period of Jupiter's magnetic field). Comparison of the resulting X-ray emission map with simultaneous far-ultraviolet images obtained by the Hubble Space Telescope imaging spectrograph (HST-STIS) shows that the northern auroral X-rays are concentrated in a ‘hot spot’ within the main ultraviolet auroral oval at high magnetic latitudes (Fig. 2).

False colour brightnesses are indicated in rayleighs (R). The observation lasted 10 h (10–20 UT) and each X-ray photon has been smeared by double the 0.4-arcsecond full-width half-maximum point-spread-function of the high-resolution camera. A jovicentric graticule with 30° intervals is overplotted, along with the maximum equatorward extent of the L = 5.9 (orange lines) and L = 30 (green lines) footprints of the VIP4 model16 magnetosphere. The auroral emissions are located at much higher latitudes than we expected on the basis of previous X-ray observations and indicate a connection with Jupiter's outer magnetosphere. An animation showing the time dependence of these observations may be viewed at http://pluto.space.swri.edu/yosemite/jupiter/chandra_hrc.html.

The mapped locations of individual X-ray photons (crosses) are overlaid on averages of several northern (left) and southern (right) auroral images made with the Hubble Space Telescope imaging spectrograph (HST-STIS) during 10–20 UT on 18 December 2000. The mapping assumes that the X-ray and ultraviolet auroras peak in emission at 240 km above the 1-bar pressure level. The size of each cross gives an approximate indication of the uncertainty in location of the corresponding X-ray photon, and only photons with emission angles of <85° are shown. The HST-STIS images made with the 25MAMA filter are displayed in false colour with auroral H2 emission brightnesses in megarayleighs (MR) as indicated by the colour bar. Surface VIP4 model16 magnetic field strength contours are shown for comparison (dark blue). The L = 5.9 and L = 30 footprints of the VIP4 model magnetosphere are also included (outer and inner green ovals, respectively), and a 10° graticule (brown dotted lines) with system III longitudes labelled. Most of the northern auroral X-rays are unexpectedly located well within the main far-ultraviolet oval and are coincident with the polar-cap far-ultraviolet emissions. The red circle in the northern auroral plot (left) shows the region defined for the hot spot used in the timing analysis. The apparent increase in X-rays toward the equator is an artefact of the polar projection.

The hot spot is located roughly at 60–70° north latitude and 160–180° system III longitude; no similar hot spot is seen in the south, but this is almost certainly due to the poor viewing geometry for the southern polar cap. We note that this same hot-spot region is the site of enhanced infrared emissions from CH4 (ref. 4), C2H2 (ref. 5), C2H4 (ref. 6) and C2H6 (ref. 7), as well as highly variable H2 emissions at far-ultraviolet wavelengths8, and a ‘dark spot’ in the sunlight reflected from Jupiter at mid-ultraviolet wavelengths12.

Jupiter's main auroral oval lies at latitudes that map magnetically to radial distances near 30 jovian radii, RJ (refs 13,14,15); the location of the hot spot at latitudes poleward of the main oval indicates that the bulk of the jovian X-ray emissions must connect along magnetic field lines to regions in the jovian magnetosphere well in excess of 30RJ from the planet. The Chandra HRC observations therefore call into question earlier views that attribute the X-ray auroral emissions to energetic particles diffusing planetward from the outer regions of the Io plasma torus and precipitating in the atmosphere at latitudes below those of the main oval3. On the other hand, our magnetic mapping of the hot spot to distances greater than 30RJ means that the source of the precipitating particles is unclear, because at such large distances from Jupiter there are insufficient S and O ions (B. H. Mauk, personal communication) to account for the hot-spot emissions. Another ion source or excitation mechanism (such as electron bremsstrahlung) must be considered.

Further evidence that some process other than energetic ion precipitation from the inner magnetosphere is responsible for the bulk of the observed auroral X-rays is provided by the lack of expected correlation between the X-ray emission morphology and the surface magnetic field strength (that is, the magnetic field strength at 1RJ) as determined with the VIP4 model16 (Fig. 2). That is, for the nominal mechanism of generation by energetic ion precipitation, the brightest X-ray emissions would be expected where the eastward drifting (that is, toward lower longitude) ions encounter the most steeply decreasing surface magnetic field strength along their L-shell footprint (that is, the locus of intersection of their magnetic field lines with the surface of Jupiter) and only if the field strength is lower than in the conjugate hemisphere17,18. Thus, although we would expect emissions at slightly higher latitudes than the L = 5.9 footprint of the Io plasma torus, at system III longitudes of 0–60° in the north and 120–260° in the south, we found minor clusters of X-rays near the L = 5.9 footprint near 140° in the north and 80–120° in the south.

A result even more puzzling than the high-latitude location of the X-ray hot spot is revealed when the X-ray counts are plotted as a function of time. The resulting light curve and power spectrum (Fig. 3) show a very strong ∼45-min oscillation in the emitted X-rays. One of the primary goals of the Chandra and HST campaigns supporting the Cassini fly-by was to search for transient auroral variations that might be related to the interaction of the solar wind with Jupiter's magnetosphere. However, correlative Cassini solar-wind data acquired upstream at about 200RJ show no comparable periodicity, even accounting for the 5–10-h delay time for the propagation from the spacecraft to the planet. Likewise, no 45-min periodicities were seen in Galileo and Cassini energetic-particle and plasma-wave measurements at the time of the Chandra observations, although such periodicities are seen at other times (W. S. Kurth, personal communication). Forty-minute oscillations have been seen before in energetic particles in the outer magnetosphere and in radio waves9,10. Following the Ulysses fly-by of Jupiter, intermittent bursts of 1–200-kHz radio emissions with an approximately 40-min period were observed for several months originating from high southern-jovian latitudes; these bursts were correlated with Ulysses measurements of solar-wind velocity and both relativistic (>8 MeV) and lower (∼50 keV) energy electrons from Jupiter9. However, the origin of these quasi-periodic radio bursts has not been explained.

a, Light curve showing the X-ray count rate measured by Chandra as a function of time for the auroral hot spot. Here we defined the hot spot region to include only those X-rays emitted within a 5°-radius circle centred on a latitude of 65° and a system III longitude of 170° (as shown by the red circle in Fig. 2). The total number of X-rays emitted from this region is 113, and the plot shows an 11-min boxcar smoothing of a 1-min binning of the data. The orange dashed line shows the projected area of the hot spot (as a percentage of the projected area of Jupiter). The times of the HST-STIS northern auroral region images shown in Fig. 2 are indicated by vertical purple lines. Unfortunately, no images were obtained during any of the bright X-ray pulses. b, Power spectrum of the hot spot signal, normalized so that, if the photons were randomly distributed over the visibility period, the mean power spectral density of any particular frequency bin would be expected to have a value of 2 (ref. 26). The peak at a period of approximately 45 min is clearly seen. The peak at 300 min is associated with the approximately 600-min rotation period of Jupiter. The dashed lines are labelled with the probability of a random signal exceeding that level in a particular frequency bin (for example, the 45-min period peak has a 4 × 10-6 likelihood of having been attained at random).

As there is no apparent correlation between the auroral X-rays and the solar-wind parameters measured by Cassini before and during the Chandra observations, it seems most likely that the oscillations arise from processes internal to the jovian magnetosphere. Global ultra-low-frequency (ULF) oscillations of the magnetic field and of the density of high-energy ions are ubiquitous in the jovian magnetosphere and are generally found to have periods in the 10–20-min range19,20. Certain models of the ULF oscillations as standing waves along magnetic field lines indicate that spacecraft motion affects the measured periods so that they are closer to one hour in a reference frame that corotates with Jupiter19. The observed ULF oscillations may arise in a resonance with the bounce periods of the energetic particles (that is, the period for a magnetically trapped ion to repeat its north–south motion along a field line). Scattering of some portion of this particle population into the loss cone could result in quasi-periodic precipitation that would account for the periodicity observed in the X-ray emissions. However, bounce periods vary with particle energy, distance from Jupiter, and pitch angle, and it is unclear what would cause a narrow range of periods to dominate this resonance over much of the magnetosphere.

It is difficult to estimate the power in the emitted X-rays, because the Chandra HRC responds over a broad energy range (0.1–10 keV) with a variable sensitivity that peaks near an energy of 1.1 keV. We currently have no knowledge of the details of the emitted spectrum, so we can only make very rough estimates of the emitted power. Assuming a photon energy of 574 eV (corresponding to an O6+ emission feature expected to be bright in ion auroras or solar-wind charge exchange21,22), the estimated X-ray luminosities of the disk of Jupiter and its northern and southern auroras are about 2.3, 1.0 and 0.4 GW, respectively. These results are consistent with previous observations made with low spatial resolution1,2.

As we note above, it is difficult to account for the ion flux needed to produce the estimated luminosities with a source region located in the outer magnetosphere. If the emissions are indeed generated by heavy-ion precipitation, one possibility is high-latitude reconnection of the planetary and solar-wind magnetic fields, with the subsequent entry of the highly ionized (but low energy) heavy-ion component of the solar wind. The captured solar-wind ions could be accelerated to MeV energies by the field-aligned currents present in the outer magnetosphere22,23,24. Such particles could also be consistent with the observed plasma waves. For example, the bounce period of 20 MeV oxygen ions on a dipole field line at L = 120RJ with an equatorial pitch angle of 30° is about 38 minutes. Although outer magnetospheric field lines are not dipolar25, they are close enough for this simple calculation to be informative. We wondered whether electron bremsstrahlung, originally rejected primarily on energetic grounds, should be reconsidered as an explanation for the X-rays. The energetics argument still holds: the power needed to produce the brightest far-ultraviolet ‘flares’ seen in the same polar-cap region as the X-ray hot spot is a few tens of TW (ref. 8), much less than the estimated power of a few PW (ref. 1) needed to produce the observed X-rays by electron bremsstrahlung. Thus, explaining the observed hot-spot X-rays with electron bremsstrahlung still seems unpromising. Whatever ultimate source is determined for the hot-spot X-rays, it should probably also account for the far-ultraviolet flare emissions, the various hydrocarbon infrared emissions, and possibly the mid-ultraviolet dark spot, as it is unlikely that these various phenomena occur in the same area of the upper atmosphere of Jupiter and yet are unrelated to one another.

References

Metzger, A. E. et al. The detection of x-rays from Jupiter. J. Geophys. Res. 88, 7731–7741 (1983).

Bhardwaj, A. & Gladstone, G. R. Auroral emissions of the giant planets. Rev. Geophys. 38, 295–353 (2000).

Mauk, B. H. et al. Hot plasma parameters of Jupiter's inner magnetosphere. J. Geophys. Res. 101, 7685–7695 (1996).

Caldwell, J. J., Halthore, R., Orton, G. & Bergstralh, J. Infrared polar brightenings on Jupiter. 4. Spatial properties of methane emission. Icarus 74, 331–339 (1988).

Drossart, P. et al. Enhanced acetylene emission near the north pole of Jupiter. Icarus 66, 610–618 (1986).

Kostiuk, T., Romani, P., Espenak, F., Livengood, T. A. & Goldstein, J. J. Temperature and abundances in the Jovian auroral stratosphere. 2. Ethylene as a probe of the microbar region. J. Geophys. Res. 98, 18823–18830 (1993).

Livengood, T. A., Kostiuk, T., Espenak, F. & Goldstein, J. J. Temperature and abundances in the Jovian auroral stratosphere. 1. Ethane as a probe of the millibar region. J. Geophys. Res. 98, 18813–18822 (1993).

Waite, J. H. Jr et al. An auroral flare at Jupiter. Nature 410, 787–789 (2001).

MacDowall, R. J. et al. Quasiperiodic jovian radio bursts: Observations from the Ulysses radio and plasma wave experiment. Planet. Space Sci. 41, 1059–1072 (1993).

Krimigis, S. M. et al. A nebula of gases from Io surrounding Jupiter. Nature 415, 994–996 (2002).

Maurellis, A. N. et al. Jovian x-ray emission from solar x-ray scattering. Geophys. Res. Lett. 27, 1339–1342 (2000).

Vincent, M. B. et al. Jupiter's polar regions in the ultraviolet as imaged by HST/WFPC2: Auroral-aligned features and zonal motions. Icarus 143, 205–222 (2000).

Connerney, J. E. P., Baron, R., Satoh, T. & Owen, T. Images of excited H+3 at the foot of the Io flux tube in Jupiter's atmosphere. Science 262, 1035–1038 (1993).

Clarke, J. T. et al. Hubble Space Telescope imaging of Jupiter's UV aurora during the Galileo orbiter mission. J. Geophys. Res. 103, 20217–20236 (1998).

Prangé, R. et al. Detailed study of FUV jovian auroral features with the post-COSTAR HST faint object camera. J. Geophys. Res. 103, 20195–20215 (1998).

Connerney, J. E. P., Acuña, M. H., Ness, N. F. & Satoh, T. New models of Jupiter's magnetic field constrained by the Io flux tube footprint. J. Geophys. Res. 103, 11929–11939 (1998).

Gehrels, N. & Stone, E. C. Energetic oxygen and sulfur ions in the jovian magnetosphere and their contribution to the auroral excitation. J. Geophys. Res. 88, 5537–5550 (1983).

Herbert, F., Sandel, B. R. & Broadfoot, A. L. Observations of the jovian UV aurora by Voyager. J. Geophys. Res. 92, 3141–3154 (1987).

Khurana, K. K. & Kivelson, M. G. Ultralow frequency MHD waves in Jupiter's middle magnetosphere. J. Geophys. Res. 94, 5241–5254 (1989).

Wilson, R. J. & Dougherty, M. K. Evidence provided by Galileo of ultra low frequency waves within Jupiter's middle magnetosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 27, 835–838 (2000).

Liu, W. & Schultz, D. R. Jovian x-ray aurora and energetic oxygen ion precipitation. Astrophys. J. 526, 538–543 (1999).

Cravens, T. E. Comet Hyakutake x-ray source: Charge transfer of heavy solar wind ions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 24, 105–108 (1997).

Bunce, E. J. & Cowley, S. W. H. Local time asymmetry of the equatorial current sheet in Jupiter's magnetosphere. Planet. Space Sci. 49, 261–274 (2001).

Krupp, N. et al. Local time asymmetry of energetic ion anisotropies in the jovian magnetosphere. Planet. Space Sci. 49, 283–289 (2001).

Smith, E. J., Davis, L. Jr & Jones, D. E. in Jupiter (ed. Gehrels, T.) 788–829 (Univ. Arizona Press, Tucson, 1976).

Leahy, D. A. et al. On searches for pulsed emission with application to four globular cluster x-ray sources: NGC 1851, 6441, 6624, and 6712. Astrophys. J. 266, 160–170 (1983).

Acknowledgements

We thank B. H. Mauk, S. Krimigis, W. S. Kurth and M. Kaiser for helpful discussions. The support of the Chandra Project and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory is gratefully acknowledged. A portion of this work is based on observations made with the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, obtained at the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gladstone, G., Waite, J., Grodent, D. et al. A pulsating auroral X-ray hot spot on Jupiter. Nature 415, 1000–1003 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/4151000a

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/4151000a

This article is cited by

-

Rotationally driven magnetic reconnection in Saturn’s dayside

Nature Astronomy (2018)

-

Imaging Plasma Density Structures in the Soft X-Rays Generated by Solar Wind Charge Exchange with Neutrals

Space Science Reviews (2018)

-

The independent pulsations of Jupiter’s northern and southern X-ray auroras

Nature Astronomy (2017)

-

The surprising southern aurora

Nature Astronomy (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.