Abstract

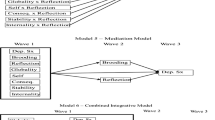

Cross-sectional and prospective research indicates that inferential feedback, a subtype of social support that addresses the cause, meaning, and consequences of negative life events, impacts depressed mood, depressogenic inferences, and depressive disorders. However, inferential feedback has not been manipulated in any prior study making it difficult to determine if it plays a causal role in depression. The current study represents the first controlled test of the role of adaptive inferential feedback in the reduction of depressive symptoms and depressogenic cognitive inferences. Individuals who received adaptive inferential feedback following a stressful life event demonstrated the greatest decreases in dysphoria and depressogenic inferences following the receipt of feedback compared to individuals who received other types of social support. Moreover, decreases in dysphoria were partially mediated by decreases in depressogenic inferences. The role of adaptive inferential feedback as a clinical tool in prevention and intervention programs is emphasized.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Abela, J. R. Z., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2000). The hopelessness theory of depression: A test of the diathesis-stress component in the interpersonal and achievement domains. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24(4), 361–378.

Abramson, L. Y., Alloy, L. B., Hogan, M. E., Whitehouse, W. G., Donovan, P., Rose, D. T., et al. (2002). Cognitive vulnerability to depression: Theory and evidence. In R. L. Leahy & E. T. Dowd (Eds.), Clinical advances in cognitive psychotherapy: Theory and application (pp. 75–92). New York: Springer.

Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., & Alloy, L. B. (1989). Hopelessness depression: A theory based subtype of depression. Psychological Review, 96, 358–372.

Alloy, L. B., & Abramson, L. Y. (1999). The Temple-Wisconsin Cognitive Vulnerability to Depression (CVD) Project: Conceptual background, design, and methods. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 13, 227–262.

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Hogan, M. E., Whitehouse, W. G., Rose, D. T., Robinson, M. S., et al. (2000). The Temple-Wisconsin Cognitive Vulnerability to Depression Project: Lifetime history of Axis I psychopathology in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 403–418.

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Tashman, N. A., Berrebbi, D. S., Hogan, M. E., Whitehouse, W. G., et al. (2001). Developmental origins of cognitive vulnerability to depression: Parenting, cognitive, and inferential feedback styles of the parents of individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. {Cognitive Therapy and Research}, 25(4), 397–423.

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., & Viscusi, D. (1981). Induced mood and the illusion of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41(6), 1129–1140.

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Whitehouse, W. G., Hogan, M. E., Tashman, N., Steinberg, D., et al. (1999). Depressogenic cognitive styles: Predictive validity, information processing and personality characteristics, and developmental origins. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 37, 503–531.

Alloy, L. B., & Clements, C. M. (1992). Illusion of control: Invulnerability to negative affect and depressive symptoms after laboratory and natural stressors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101(2), 234–245.

Barnett, P. A., & Gotlib, I. H. (1988). Psychosocial functioning and depression: Distinguishing among antecedents, concomitants, and consequences. Psychological Bulletin, 104(1), 97–126.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Garbin, M. G. (1988). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 8, 77–100.

Chartier, G. M., & Ranieri, D. J. (1989). Comparison of two mood induction procedures. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 13(3), 275–282.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357.

Crossfield, A. G., Alloy, L. B., Gibb, B. E., & Abramson, L. Y. (2002). The development of depressogenic cognitive styles: The role of negative childhood life events and parental inferential feedback. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 16(4), 487–502.

DeFronzo, R., & Cascardi, M. (2000). The Relationship Questionnaire. Unpublished questionnaire.

DeFronzo, R., & Panzarella, C. (1999, August). Attachment, support seeking, and adaptive feedback: Implications for psychological health. Poster session presented at the 107th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Boston, MA.

DeFronzo, R., & Panzarella, C. ( 2000, November). Adaptive feedback and its salubrious impact on a wide range of psychosocial variables for the insecurely attached. Poster session presented at the 34th Annual Convention of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy, New Orleans, LA.

DeFronzo, R., Panzarella, C., & Alloy, L. B. (2000). The Expectation Questionnaire. Unpublished questionnaire.

DeFronzo, R., Panzarella, C., & Butler, A. C. (2001). Attachment, support seeking, and adaptive feedback: Implications for psychological health. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 8, 48–52.

Doherty, K., & Schlenker, B. R. (1995). Excuses as mood protection: The impact of supportive and challenging feedback from others. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 14(2), 147–164.

Fava, G. A., Fabbri, S., & Sonino, N. (2002). Residual symptoms in depression: An emerging therapeutic target. Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 26, 1019–1027.

Follette, V. M., & Jacobson, N. S. (1987). Importance of attributions as predictor of how people cope with failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 1205–1211.

Gable, S. L., Reis, H. T., & Downey, G. (2003). He said, she said: A quasi-signal detection analysis of daily interactions between close relationship partners. Psychological Science, 14(2), 100–105.

Gibb, B. E., Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., & Marx, B. P. (2003). Childhood maltreatment and maltreatment-specific inferences: A test of Rose and Abramson's (1992) extension of the hopelessness theory. Cognition and Emotion, 17(6), 917–931.

Gottlieb, B. H. (1996). Theories and practices of mobilizing social support in stressful circumstances. Handbook of stress, medicine, & health (pp. 339–356) Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. Heller, K., & Rook, K. S. (1997). Distinguishing the theoretical functions of social ties: Implications for support interventions. In S. Duck (Ed.), Handbook of personal relationships: Theory, research, and interventions (pp.649-670). Chichester, England:Wiley.

Hopkins, W. G. (2000). A scale of magnitudes for effect statistics. A new view of statistics. Retrieved on January 25, 2004, from http://www.sportsci.org/resource/stats/effectmag.html

Houston, D. M. (1995). Surviving a failure: Efficacy and a laboratory based test of the hopelessness model of depression. European Journal of Social Psychology, 25, 545–558. Lakey, B., & Drew, J. B. (1997). A social-cognitive perspective on social support. In G. R. Pierce, B. Lakey, I. G. Sarason, & B. R. Sarason (Eds.), Sourcebook of social support and personality (The Plenum Series in Social/Clinical Psychology, pp.107-134). New York: Plenum Press. Lakey, B., & Lutz, C. J. (1996). Social support and preventive and therapeutic interventions. In G. R. Pierce, B. R. Sarason, & I. G. Sarason (Eds.), Handbook of social support and the family (pp.435-465). New York: Plenum Press.

Majon on-line IQ test section (n.d.). Retrieved August 1, 2000, from majon online IQ tests; seriously entertaining IQ tests

Mehlman, R. C., & Synder, C. R. (1985). Excuse Theory: A test of the protective role of attributions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49(4), 994–1007.

Metalsky, G. I., Abramson, L. Y., Seligman, M. E. P., Semmel, A., & Peterson, C. R. (1982). Attributional styles and life events in the classroom: Vulnerability and invulnerability to depressive mood reactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 612–617.

Metalsky, G. I., Halberstadt, L. J., & Abramson, L. Y. (1987). Vulnerability to depressive mood reactions: Toward a more powerful test of the diathesis-stress and causal mediation components of the reformulated theory of depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 386–393.Panzarella, C., & Alloy, L. B. (1995). Social support, hopelessness, and depression: An expanded hopelessness model. In L. B. Alloy (Chair), The hopelessness theory of depression: New developments in theory and research. Symposium conducted at the 29th annual convention of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy, Washington, DC.

Panzarella, C., Alloy, L. B., & Whitehouse, W. G.(2004). Expanded hopelessness theory of depression: On the mechanisms by which social support protects against depression. Manuscript in submission.

Peterson, C., & Villanova, P. (1988). An expanded attributional style questionnaire. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97, 87–89. Pierce, G. R., Sarason, I. G., & Sarason, B. R. (1996). Coping and social support. In M. Zeidner & N. S. Endler (Eds.), Handbook of coping: Theory, research, and applications (pp. 434-451). New York: Wiley

Roberts, J. E., & Gotlib, I. H. (1997). Social support and personality in depression: Implications from quantitative genetics. In G. R. Pierce, B. Lakey, I. G. Sarason, & B. R. Sarason (Eds.), Sourcebook of social support and personality (The Plenum Series in Social/Clinical Psychology, pp. 187–214). New York: Plenum Press.

Sacks, C. H., & Bugental, D. B. (1987). Attributions as moderators of affective and behavioral responses to social failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 939–947. Sarason, B. R., Sarason, I. G., & Gurung, R. A. R. (1997). Close personal relationships and health outcomes: A key to the role of social support. In S. Duck (Ed.), Handbook of personal relationships: Theory, research, and interventions (pp. 547-573). Chichester, England: Wiley.

Sarason, B. R., Sarason, I. G., & Pierce, G. R. (1990). Social support: An interactional view. New York: Wiley.

Seligman, M. E. P., Abramson, L. Y., Semmel, A., & von Baeyer, C. (1979). Depressive attributional style. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 88, 242–247.

Seriously entertaining IQ tests. (n.d.). Retrieved on August 1, 2000, from majon online IQ tests; seriously entertaining IQ tests

Stiensmeier-Pelster, J. (1989). Attributional style and depressive mood reactions. Journal of Personality, 57(3), 581–599.

Thase, M. E., Friedman, E. S., & Howland, R. H. (2001). Management of treatment-resistant depression: Psychotherapeutic perspectives. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62(18), 18–24. Turner, R. J. (1999). Social support and coping. In A. V. Horwitz & T. L. Scheid (Eds.), A handbook for the study of mental health. Social contexts, theories, and systems (pp. 198-210). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Turner-Cobb, J. (2000). Social support and salivary cortisol in women with metastatic breast cancer. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62(3), 337–345.

Vander Voort, D. (1999). Quality of social support in mental and physical health. Current Psychology: Developmental, Learning, Personality, and Social, 18(2), 205–222.

Zuckerman, M., & Lubin, B. (1965). Multiple Affect Adjective Checklist. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dobkin, R.D., Panzarella, C., Fernandez, J. et al. Adaptive Inferential Feedback, Depressogenic Inferences, and Depressed Mood: A Laboratory Study of the Expanded Hopelessness Theory of Depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research 28, 487–509 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1023/B:COTR.0000045560.71692.88

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/B:COTR.0000045560.71692.88