Abstract

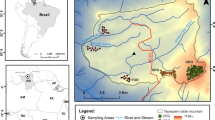

I analyzed the distribution of Acanthaceae, Araceae, Bromeliaceae, Cactaceae, Melastomataceae, and Pteridophyta in 62 vegetation plots of 400 m2 along an elevational transect between 500 m and 2450 m, and at a nearby lowland site in western Santa Cruz department, Bolivia. These groups were selected because they are physiognomically distinctive, have high species numbers, are comparatively easy to identify, adequately reflect overall floristic relationships, include a wide range of life forms, and are small. The transect was located in the Tucumano-Boliviano biogeographic zone and included drought-deciduous (<850–1000 m), mixed evergreen (850–1000 m to 1800 m), and evergreen Podocarpus-dominated (>1800 m) forests. Elevational patterns of species richness were group-specific and probably related to the ecophysiological properties of each group. Species richness in Pteridophyta and Melastomataceae was correlated with moss cover (i.e., humidity), with elevation (i.e., temperatures) in Acanthaceae and epiphytic Bromeliaceae, with potential evapotranspiration (i.e., ecosystem productivity) in Araceae, and with light availability at ground level in terrestrial Bromeliaceae and Cactaceae. Community endemism generally increased with elevation, but showed a maximum at 1700 m for terrestrial Pteridophyta, and a nonsignificant decline for epiphytic Bromeliaceae and Cactaceae. Endemism was higher for terrestrial than for epiphytic taxa, and was lower among Pteridophyta compared to all other groups, reflecting different dispersal ability among taxonomic and ecological groups. Elevational zonation, tested against a null-model of random distribution of elevational limits, revealed a significant accumulation of upper and lower elevational range boundaries at 900–1050 m and at 1500–1850 m, corresponding to the elevational limits of the main physiognomic vegetation types.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Austin, M. P. 1985. Continuum concept, ordination methods, and niche theory. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 16: 39–61.

Backeberg, C. 1979. Das Kakteenlexikon. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Jena.

Balslev, H. 1988. Distribution patterns of Ecuadorean plant species. Taxon 37: 567–577.

Balslev, H., Valencia, R., Paz y Miñ o, G. Christensen, H. & Nielsen, I. 1998. Species count of vascular plants of humid lowland forest in Amazonian Ecuador. Pp. 585–594. In: Dallmeier, F. & Comiskey, J. A. (eds), Forest biodiversity in North, Central and South America and the Caribbean. Man and the Biosphere Series, Vol. 21. The Parthenon Publishing Group, Carnforth, U.K.

Barthlott, W., Lauer, W. & Placke, A. 1996. Global distribution of species diversity in vascular plants: towards a world map of phytodiversity. Erdkunde 50: 317–327.

Beck, S. G., Libermann C., M., Pedrotti, F. & Venanzoni, R. 1992. Estado actual de los bosques en la cuenca del Río Camacho (Departamento de Tarija-Bolivia). Studi Geologici Camerini, Vol. speziale 1992: 41–61.

Bianchi, R. 1981. Las Precipitaciones del Noroeste Argentino. Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria, Salta, Argentina.

Fjeldså , J., Kessler, M. & Swanson, G. 1999. Cocapata and Saila Pata. People and biodiversity in an Andean valley. DIVA technical report no 7. National Environmental Research Institute, Kalø , Denmark.

Brown, A. D., Chalukian, S. D. & Malmierca, L. M. 1985. Estudio florístico-estructural de un sector de selva semidecidua del noroeste argentino. I. Composició n florística, densidad y diversidad. Darwiniana 26: 27–41.

Cabrera, A. L. 1976. Regiones fitogeográficas Argentinas. Enciclopedia Argentina de Agricultura y Jardinería. Ed. 2(1): 1–85.

Chao, A. 1984. Non-parametric estimation of the number of classes in a population. Scand. J. Stat. 11: 265–270.

Cody, M. L. 1986. Diversity, rarity, and conservation in Meditarranean-climate regions. Pp. 123–152. In: Soulé, M. (ed.), Conservation biology: the science of scarcity and diversity. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts.

Colwell, R. K. & Coddington, J. A. 1995. Estimating terrestrial biodiversity through extrapolation. Pp. 101–118. In: Hawksworth, D. L. (ed.), Biodiversity: Measurement and Estimation. Chapman and Hall, London.

Colwell, R. K. & Hurtt, G. C. 1994. Nonbiological gradients in species richness and a spurious Rapoport effect. Am. Nat. 144: 570–595.

Croat, T. B. 1995. Floristic comparisons of Araceae in six Ecuadorian florulas. Pp. 489–499. In: Churchill, S. P., Balslev, H., Forero, E. & Luteyn, J. L. (eds), Biodiversity and conservation of neotropical montane forests. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx.

Davidse, G., Sousa S., M. & Knapp, S. (general eds), 1995. Flora Mesoamericana. Vol. 1. Psilotaceae a Salviniaceae. Univ. Nac. Autó noma de México, México, D.F.

Davis, S. D., Heywood, V. H., Herrera-MacBryde, O., Villa-Lobos, J. & Hamilton, A. C. (eds). 1997. Centres of plant diversity. A guide and strategy for their conservation, Vol. 3. The Americas. WWF/IUCN, Washington, D.C.

de la Sota, E. R. 1977. Flora de la Provincia de Jujuy, Repú blica Argentina. Parte II. Pteridophyta. INTA, Buenos Aires.

Dinerstein, E., Olson, D. M., Graham, D. J., Webster, A. L., Primm, S. A., Bookbinder, M. P. & Ledec, G. 1995. A conservation assessment of the terrestrial ecoregions of Latin America and the Caribbean. The World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Eriksen, W. 1986. Frostwechsel und hygrische Bedingungen in der Punastufe Boliviens: Ein Beitrag zur Ökoklimatologie der randtropischen Anden. Pp. 1–21. In: Buchholz, H. J. (ed.), Bolivien: Beiträge zur physischen Geographie eines Andenstaates. Jahrb. Geogr. Gesellsch. Hannover, 1985.

Fjeldså , J. 1994. Geographical patterns for relict and young species of birds in Africa and South America and implications for conservation priorities. Biodiv. Cons. 3: 207–226.

Fjeldså , J., Lambin, E. & Mertens, B. 1999. Correlation between endemism and local ecoclimatic stbility documented by comparing Andean bird distributions and remotely sensed land surface data. Ecography 22: 63–78.

Fjeldså , J. & Mayer, S. 1996. Recent ornithological surveys in the Valles region, southern Bolivia and the possible role of Valles for the evolution of the Andean avifauna. DIVA technical report no 1. National Environmental Research Institute, Kalø , Denmark.

Fjeldså , J. & Rahbek, C. 1997. Species richness and endemism in South American birds: implications for the design of networks of nature reserves. Pp. 466–482. In: Laurance, W. F. & Bierregaard, R. (eds), Tropical forest remnants: ecology, management and conservation of fragemented communities. Chicago University Press, Chicago.

Frahm, J.-P. & Gradstein, S. R. 1991. An altitudinal zonation of tropical rain forests using bryophytes. J. Biogeogr. 18: 669–678.

Gentry, A. H. 1988. Changes in plant community diversity and floristic composition on environmental and geographical gradients. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 75: 1–34.

Gentry, A. H. 1995. Patterns of diversity and floristic composition in neotropical montane forests. Pp. 103–126. In: Churchill, S. P., Balslev, H., Forero, E. & Luteyn, J. L. (eds), Biodiversity and conservation of neotropical montane forests. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx.

Gentry, A. H. & Dodson, C. H. 1987. Contribution of nontrees to species richness of a tropical rain forest. Biotropica 19: 149–156.

Gerold, G. 1987. Untersuchungen zur Klima-, Vegetations-, Höhenstufung und Bodensequenz in SE-Bolivien. Ein randtropisches Profil vom Chaco bis zur Puna. Pp. 1–70. In: Beiträge zur Landeskunde Boliviens. Geographisches Institut der RWTH Aachen, Germany.

Grau, H. R. & Brown, A. D. 1995. Patterns of tree species diversity along latitudinal and altitudinal gradients in the Argentinian subtropical montane forests. Pp. 295–300. In: Churchill, S. P., Balslev, H. Forero, E. & Luteyn, J. L. (eds), Biodiversity and conservation of neotropical montane forests. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx.

Graves, G. L. 1985. Elevational correlates of speciation and interspecific geographic variation in plumage in Andean forest birds. Auk 102: 556–579.

Gurung, V. D. L. 1985. Ecological observations on the pteridophyte flora of Langtang National Park, central Nepal. Fern Gaz. 13: 25–32.

Henderson, A., Galeano, G. & Bernal, R. 1995. Field Guide to the Palms of the Americas. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Holdridge, L. R., Grenke,W. C., Hatheway, W. H., Liang T. & Tosi, J. A. 1971. Forest environments in tropical life zones: a pilot study. Pergamon Press, Oxford.

Hueck, K. & Seibert, P. 1981. Vegetationskarte von Südamerika. 2nd ed. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart, Germany.

Ibisch, P. L. 1996. Neotropische Epiphytendiversität -das Beispiel Bolivien. Archiv naturwissenschaftlicher Disertationen 1. Martina Galunder-Verlag, Wiehl, Germany.

Ibisch, P. L., Boegner, A., Nieder, J. & Barthlott, W. 1996. How diverse are neotropical epiphytes? An analysis based on the 'Catalogue of the flowering plants and gymnosperms of Peru'. Ecotropica 1: 13–28.

Karson, M. J. 1982. Multivariate statistical methods. Iowa University Press, Iowa.

Kessler, M. 2000. Altitudinal zonation of Andean cryptogam communities. J. Biogeogr. 27: 275–282.

Kessler, M. & Bach, K. 1999. Using indicator groups for vegetation classification in species-rich Neotropical forests. Phytocoenologia 29: 485–502.

Kessler, M., Krömer, T. & Jimenez, I. In Press. Inventario de grupos selectos de plantas en el Valle de Masicurí, Santa Cruz. Rev. Boliviana de Ecología y Conservació n Ambiental.

Kitayama, K. 1992. An altitudinal transect study of the vegetation of Mount Kinabalu, Borneo. Vegetatio 102: 149–171.

Krömer, T., Kessler, M., Holst, B. K., Luther, H. E., Gouda, E., Till, W., Ibisch, P. L. & Vásquez, R. 1999. Checklist of Bolivian Bromeliaceae with notes on species distribution and levels of endemism. Selbyana 20: 201–223.

Levins, R. & Lewontin, R. 1982. Dialectics and reductionism in ecology. Pp. 107–138. In: Saarinen, E. (ed.), Conceptual issues in ecology. D. Reidel Publ. Co., Dortrecht, Holland.

Lieberman, D., Lieberman, M., Peralta, R. & Hartshorn, G. S. 1996. Tropical forest structure and composition on a large-scale altitudinal gradient in Costa Rica. J. Ecol. 84: 137–152.

Lieth, H. 1975. Modeling the primary productivity of the world. Pp. 237–263. In: Lieth, H. & Whittaker, R. H. (eds), Primary Productivity of the biosphere. Springer-Verlag, New York.

McCullogh, P. & Nelder, J. A. 1983. Generalized linear models. Chapman & Hall, London.

Morales, C. de. 1990. Bolivia. Medio ambiente y ecología aplicada. Instituto de Ecología, UMSA, La Paz.

Moyano, M. Y. & Movia, C. P. 1989. Relevamiento fisonomicoestructural de la vegetació n de las Sierras de San Javier y El Periquillo. Lilloa 37: 123–135.

Myers, N. 1988. Threatened biotas: 'hot spots' in tropical forests. The Environmentalist 10: 243–256.

Navarro, G. 1996. Catálogo ecoló gico preliminar de las cactáceas de Bolivia. Lazaroa 17: 33–84.

Navarro, G. 1997. Contribució n a la clasificació n ecoló gica y florística de los bosques de Bolivia. Rev. Boliviana Ecol. 2: 3–38.

Pareja, J., Vargas, C., Suárez, R., Balló n, R., Carrasco, R. y Villarroel, C. 1978. Mapa geoló gico de Bolivia. YPFB-Servicio Geoló gico de Bolivia, La Paz.

Parker, T. A. III, Gentry, A. H., Foster, R. B., Emmons, L. H. & Remsen, J. V., Jr. 1993. The lowland dry forests of Santa Cruz, Bolivia: A global conservation priority. RAP Working Papers 4. Conservation International. Washington, D.C.

Rahbek, C. 1995.The elevational gradient of species richness: a uniform pattern? Ecography 18: 200–205.

Rahbek, C. 1997. The relationship among area, elevation, and regional species richness in neotropical birds. Am. Nat. 149: 875–902.

Ribera, M. O., Libermann, M., Beck, S. & Moraes, M. 1992. Vegetació n de Bolivia. Pp. 169–222. In: Mihotek B., K. (ed.), Comunidades, Teritorios Indígenas y Biodiversidad en Bolivia. U.A.G.R.M.-CIMAR, Santa Cruz, Bolivia.

Richter, M. & Lauer, W. 1987. Pflanzenmorphologische Merkmale der hygrischen Klimavielfalt in der Ost-Kordillere Boliviens. Pp. 71–108. In: Gerold, G., Köster, G., Lauer, W., Mahnke, L. & Richter, M. (eds), Beiträge zur Landeskunde Boliviens. Geogr. Inst. RWTH Aachen, Germany.

Ritter, F. 1980. Kakteen in Südamerika. Vol. 2. Argentinien/ Bolivien. Friedrich Ritter Selbstverlag, Spangenberg, Germany.

Rosenzweig, M. L. 1968. Net primary productivity of terrestrial communities: prediction from climatic data. Am. Nat. 102: 67–74.

Rosenzweig, M. L. 1995. Species diversity in space and time. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Saldias P., M. 1991. Inventario de árboles en el bosque alto del Jardín Botánico de Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Ecol. Bolivia 17: 31–46.

Schulenberg, T. S. & Awbrey, K. 1997. A rapid assessment of the humid forests of South Central Chuquisaca. Bolivia. RAP Working Papers 8. Conservation International. Washington, D.C.

Shipley, B. & Keddy, P. A. 1987. The individualistic and community-unit concepts as falsifiable hypotheses. Vegetatio 69: 47–55.

Smith, A. R. 1972. Comparison of fern and flowering plant distributions with some evolutionary interpretations for ferns. Biotropica 4: 4–9.

Smith, L. B. & Downs, R.vJ. 1974- 1979. Bromeliaceae. Flora Neotropica Monograph 14, Parts 1- 3. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York.

Sokal, R. R. & Rohlf, F.vJ. 1995. Biometry. 3rd edn. Freeman, New York

Steyermark, J. A., Berry, P. E. & Holst, B. K. (eds), 1995. Flora of the Venezuelan Guayana, Vol. 2. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon.

SYSTAT. 1997. SYSTAT for Windows, statistics, version 7.0. SPSS Inc., Chicago.

Terborgh, J. & Winter, B. 1983. A method for siting parks and reserves with special reference to Colombia and Ecuador. Biol. Cons. 27: 45–58.

Thornthwaite, C. W. & Mather, J. R. 1957. Instructions and tables for computing potential evapotranspiration and the water balance. Drexel Institute of Technology, Laboratory of Climatology, Publications on Climatology 10: 181–311.

Tryon, R. M. 1985. Fern speciation and biogeography. Proc. Royal Soc. Edinburgh 86B: 353–360.

Tryon, R. M. & Stolze, R. G. 1989-1994. Pteridophyta of Peru. Parts I-VI. Fieldiana Botany 20: 1–145; 22: 1- 128; 27: 1- 176; 29: 1- 80; 32: 1- 190; 34: 1- 123.

van derWerff, H. 1990. Ferns as indicators of vegetation types in the Galapagos Archipelago. Mongr. Syst. Bot. Missouri Bot. Gard. 32: 79–92.

Vásquez, J. A. & Givnish, T. J. 1998. Altitudinal gradients in tropical forest composition, structure, and diversity in the Sierra de Manantlán. J. Ecol. 86: 999–1020.

Williams, P. H. & Humphries, C. J. 1994. Biodiversity, taxonomic relatedness, and endemism in conservation. Pp. 269–287. In: Forey, P. L., Humphries, C. J. & Vane-Wright, R. I. (eds), Systematics and conservation evaluation. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Wolf, J. H. D. 1993. Diversity patterns and biomass of epiphytic bryophytes and lichens along an altitudinal gradient in the northern Andes. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 80: 928–960.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kessler, M. Elevational gradients in species richness and endemism of selected plant groups in the central Bolivian Andes. Plant Ecology 149, 181–193 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026500710274

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026500710274