Abstract

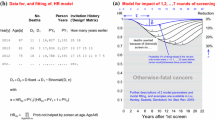

Despite rapid advances in medicine and beneficial lifestyle changes, the incidence and mortality rate of gynecologic carcinoma remains high worldwide. This paper presents the econometric model findings of the major drivers of breast cancer mortality among US women. The results have implications for public health policy formulation on disease incidence and the drivers of mortality risks. The research methodology is a fixed-effects GLS regression model of breast cancer mortality in US females age 25 and above, using 1990–1997 time-series data pooled across 50 US states and DC. The covariates are age, years schooled, family income, 'screening' mammography, insurance coverage types, race, and US census region. The regressions have strong explanatory powers. Finding education and income to be significantly and positively correlated with mortality supports the 'life in the fast lanes' hypothesis of Phelps. The policy of raising a woman's education at a given income appears more beneficial than raising her income at a given education level. The relatively higher mortality rate for Blacks suggests implementing culturally appropriate set of disease prevention and health promotion programs and policies. Mortality differs across insurance types with Medicaid the worst suggesting need for program reform. Mortality is greater for women ages 25–44 years, females 40–49 years who have had screening mammography, smokers, and residents of some US states. These findings suggest imposing more effective tobacco use control policies (e.g., imposing a special tobacco tax on adult smokers), creating a more tractable screening mammography surveillance system, and designing region-specific programs to cut breast cancer mortality risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

R.D. Auster, I. Leveson and D. Sartachek, The production of health: An exploratory study, Journal of Human Resources 4 (1969) 411-436.

Author Unknown, Use of mammography - United States, 1990, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 39 (1990) 621, 627-630.

C.B. Begg, The search for cancer risk factors: When can we stop looking? American Journal of Public Health 91(3) (2001) 360-364.

E.E. Calle et al., Demographic predictors of mammography and pap smear screening in US women, American Journal of Public Health 83(1) (1993) 53-59.

R.A. Catalano and W.A. Satariano, Unemployment and the likelihood of detecting early stage breast cancer, American Journal of Public Health 88(4) (1998) 586-589.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; online http://www.cdc.gov/ (11 February) (2000).

A. Chandra and J. Skinner, Geography and racial disparities, NBER Working Paper 9513 (February 2003).

H. Corman and M. Grossman, Determinants of neonatal mortality rate in the US: A reduced form model, Journal of Health Economics 4 (1985) 213-236.

J. Currie and J. Gruber, Public health insurance and medical treatment: The equalizing impact of the Medicaid expansions, Journal of Public Economics 82 (2001) 63-89.

S.L. Decker and K. Hempstead, HMO penetration and quality of care: The case of breast cancer, Journal of Health Care Finance 26(1) (1999) 18-32.

S. Dobie et al., Obstetric care and payment source: Do low-risk Medicaid women get less care? American Journal of Public Health 88(1) (1998) 51-56.

V.J. Duncan, R.L. Parrott and K.J. Silk, African American women's perceptions of the role of genetics in breast cancer risk, American Journal of Health Studies 17(2) (2001) 50-58.

J.A. Earp et al., Increasing use of mammography among older, rural African American women: Results from a community trial, American Journal of Public Health 92(4) (2002) 646-654.

J.G. Elmore, D.L. Miglioretti, L.M. Reisch et al., Screening mammograms by community radiologists: Variability in false-positive rates, Journal of the National Cancer Institute 94(18) (2002) 1373-1380.

J.G. Elmore, V.M. Moceri, D. Carter and E.B. Larson, Breast carcinoma tumor characteristics in Black and White women, Cancer 83(12) (1998) 2509-2515.

J.W. Ely et al., Racial differences in survival from breast cancer, results of the National Cancer Institute Black/White cancer survival study, Journal of the American Medical Association 272(12) (1994) 947-954.

V.L. Ernester, Mammography screening for women aged 40 through 49 - a guidelines saga and a clarion call for informed decision making, American Journal of Public Health 87(7) (1997) 1103-1106.

J.J. Escario and J.A. Molina, Do tobacco taxes reduce lung cancer mortality? Working Paper 2000-17/FEDEA, RePEc, 2000; online http://netec.mcc.ac.uk/WoPEc/data/Papers/fdafdaddt2000-17.html

R.G. Evans et al., Why Are Some People Healthy and Others Not? The Determinants of Health of Populations (Aldine Gruyter, Hawthorne, New York, 1994).

L.L. Fajardo et al., Factors influencing women to undergo screening mammography, Radiology 184(1) (1992) 59-63.

P.J. Feldstein, Health Care Economics, 5th Ed. (Delmar Publishers, New York, 1999).

J.B. Figueroa and N. Breen, Significance of underclass residence on the stage of breast and cervical cancer diagnosis, The American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 85(2) (1995) 112-116.

J.A. Flaws and T.L. Bush, Racial differences in drug metabolism: An explanation for higher breast cancer mortality in blacks? Medical Hypotheses 50 (1998) 327-329.

S. Folland, A.C. Goodman and M. Stano, The Economics of Health and Health Care (Prentice Hall, New Jersey, 1997).

D.M. Fox, Comment: Epidemiology and the new political economy of medicine, American Journal of Public Health 89(4) (1999) 493-496.

E. Frazao, America's Eating Habits: Changes and Consequences (USDA Information Bulletin #750, Washington, DC, USDA, 2000).

V.R. Fuchs, Who Shall Live? (Basic Books, New York, 1974).

V.R. Fuchs, Time preference and health: An exploratory study, in: Economic Aspects of Health, ed. V.R. Fuchs (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, 1982).

V.R. Fuchs, M. McClellan and J. Skinner, Area differences in utilization of medical care and mortality among US elderly, NBERWorking Paper No. 8628 (December 2001).

M.T. Fullilove, Comment: Abandoning “race” as a variable in public health research - an idea whose time has come, American Journal of Public Health 88(9) (1998) 1297-1298.

U.-G. Gerdtham and C.J. Ruhm, Deaths rise in good economic times: Evidence from the OECD, NBERWorking Paper No. 9357 (December 2002).

J.S. Goodwin et al., Geographic variations in breast cancer mortality: Do higher rates imply elevated incidence or poorer survival? American Journal of Public Health 88(3) (1998) 458-460.

J.F. Griffin et al., The effect of a Medicaid managed care program on the adequacy of prenatal care utilization in Rhode Island, American Journal of Public Health 89(4) (1999) 497-501.

M. Grossman, On the concept of health capital and the demand for health, Journal of Political Economy 80 (1972) 223-255.

J. Hadley, More Medical Care, Better Health? (The Urban Institute, Washington, DC, 1982).

J. Hadley, Medicare spending and mortality rates of the elderly, Inquiry 25 (1988) 485-493.

K.E. Heck et al., Socioeconomic status and breast cancer mortality, 1989 through 1993: An analysis of education data from death certifi-cates, American Journal of Public Health 87(7) (1997) 1218-1222.

N. Holtzman, Genetic screening and public health, American Journal of Public Health 87 (1997) 1275-1276.

J. Jacobellis and G. Cutter, Mammography screening and differences in stage of disease by race/ethnicity, American Journal of Public Health 92(7) (2002) 1144-1150.

Jacobs Institute of Women's Health, Mammography Attitudes and Usage Study, 1992: Executive Summary (Jacobs Institute of Women's Health, Washington, DC).

B. Kirkman-Liff and J. Kronenfeld, Access to cancer screening services for women, American Journal of Public Health 82(5) (1992) 733-735.

J. Kmenta, Elements of Econometrics, 2nd Ed. (Macmillan Publishing Co., New York, 1986).

H.C. Kraemer and M.A. Winkleby, Do we ask too much from community-level interventions or from intervention researchers? American Journal of Public Health 87(10) (1997) 1727.

N. Krieger, Is breast cancer a disease of affluence, poverty, or both? The case of African-American women, American Journal of Public Health 92(4) (2002) 611-613.

S.E. Kutner, Breast cancer genetics and managed care: The Kaiser Permanente experience, Cancer 86(S11) (1999) 2570-2574.

J.F. Lando, K.E. Heck and K.M. Brett, Hormone replacement therapy and breast cancer risk in a nationally representative cohort, American Journal of Preventive Medicine 17(3) (1999) 176-180.

D.S. Lane, A.P. Polednak and B.A. Burg, Breast cancer screening practices among users of county-funded health centers vs women in the entire community, American Journal of Public Health 82(2) (1992) 199-203.

B. Liebman, Dodging cancer with diet, Nutrition Action Newsletter 22(1) (1995) 4-6.

J.W. Lynch et al., Income inequality and mortality in metropolitan areas of the United States, American Journal of Public Health 88(7) (1998) 1074-1080.

D.M. Makuc et al., Health insurance and cancer screening among women, in: Advanced Data254 (US Department of Health and man Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Atlanta, GA, 1994).

J.S. Mandelblatt, K. Gold and A.S. O'Malley, Breast and cervix cancer screening among multiethnic women: Role of age, health and source of care, Preventive Medicine 28(1999) 418-425.

J.S. Mandelblatt, J.F. Kerner, J. Hadley et al., Variations in breast carcinoma treatment in older Medicare beneficiaries, Cancer 95 (2002) 1401-1414.

W.G. Manning, A. Leibowitz, G.A. Goldberg et al., A controlled trial of the effect of a prepaid group practice on use of services, New England Journal of Medicine 310(23) (1984) 1505-1510.

P. McDonough et al., Income dynamics and adult mortality in the United States, 1972 through 1989, American Journal of Public Health 87(9) (1997) 1476-1483.

H.G. Muntz, “Curbside” consultations in gynecologic oncology: A closer look at a common practice, Gynecological Oncology 74(3) (1999) 456-459.

National Cancer Institute, Cancer Facts: Breast Cancer Screening, December 1992 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, 1993).

National Cancer Institute, Screening mammograms, PDQ screening and prevention for health Professionals (http://my.webmd.com/content/ dmk/dmk_article_58155) (accessed 12 March 2000).

A.A. Okunade, C.F. Chang and R.D. Evans, Comparative analysis of regression output summary statistics in common statistical packages, The American Statistician 47(4) (1993) 298-303.

M.R. Partin and J.E. Korn, Questionable data and preconceptions: Reconsidering the value of mammography for American Indian women, American Journal of Public Health 87(7) (1997) 1100-1102.

C.E. Phelps, Health Economics (Harper Collins Publishers, New York, 1992).

R. Pindyck and D. Rubinfeld, Econometric Models and Economic Forecasts (McGraw Hill, New York, 1991).

R.G. Roetzheim et al., Effects of health insurance and race on breast carcinoma treatments and outcomes, Cancer 89(11) (2000) 2202-2213.

M.C. Romans, Utilization of mammography: Social and behavioral trends, Cancer 72(4) (1993) 1475-1477.

C.J. Ruhm, Are recessions good for your health? Quarterly Journal of Economics 115(2) (2000) 617-650.

A. Schatzkin, Annotation: Disparity in cancer survival and alternative health care financing systems, American Journal of Public Health 87(7) (1997) 1095-1096.

F. Schmidt, K.A. Hartwagner, E.B. Spork and R. Groell, Medical audit after 26,711 breast imaging studies: Improved rate of detection of small breast carcinomas, Cancer 83 (1998) 2516-2520.

S. Selvin, Statistical Analysis of Epidemiological Data (Oxford University Press, New York, 1991).

S. Selvin et al., Breast cancer mortality detection: Maps of 2 San Francisco Bay area counties, American Journal of Public Health 88(8) (1998) 1186-1192.

M. Siahpush and G.K. Singh, Sociodemographic variations in breast cancer screening behavior among Australian women: Results from the 1995 National Health Survey, Preventive Medicine (35) (2002) 174-180.

T.L. Skaer et al., Breast cancer mortality declining but screening among subpopulations lags (Letter to the Editor), American Journal of Public Health 88(2) (1998) 307-308.

C.M. Sox, K. Swartz, H.R. Burstin and T.A. Brennan, Insurance or a regular physician: Which is the most powerful predictor of health care? American Journal of Public Health 88(3) (1998) 364-370.

E. Ubell, Stepping up the fight against breast cancer, PARADE (11 September) (1994) 24.

US Census Bureau, March Current Population Survey and Current Population Reports; online http://www.census.org/ (data retrieved 2 February 2000).

US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis; online http://www.bea.doc.gov/ (data retrieved on 8 February 2000).

US Government, Statistical Abstracts of the United States (USGPO, Washington, DC, 1999).

US Preventive Services Task Force, Chemoprevention of breast cancer: Recommendations and rationale, Annals of Internal Medicine 137(1) (2002) 56-58.

J.B. Walter, An Introduction to the Principles of Diseases (W.B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia, PA, 1977).

H. Wang, S.O. Thoresen and S. Tretti, Breast cancer in Norway 1970- 1993: A population-based study on incidence, mortality and survival, British Journal of Cancer 77(9) (1998) 1519-1524.

WebMdSM Health, How can breast cancer be prevented? http://my. webmd.com/content/dmk/dmk_article_5461968 (accessed 12 March 2000) 1-5.

B.L. Wells and J.W. Horm, Targeting the underserved breast for cervical cancer screening: The utility of ecological analysis using the National Health Interview Survey, American Journal of Public Health 88(10) (1998) 1484-1488.

K.J. White, SHAZAMEconometrics Computer Program User'sManual (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1993).

M.D. Wong, W. Shapiro, W.J. Boscardin and S.L. Ettner, Contribution of major diseases to disparities in mortality, New England Journal of Medicine 347(20) (2002) 1585-1592.

M. Yu, A.D. Seetoo, C.K. Tsai and C. Sun, Sociodemographic predictors of Papanicolaou mear test and mammography use among women of Chinese descent in southeastern Michigan, Women's Health Issues 8(6) (1998) 372-381.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Okunade, A.A., Karakus, M.C. Mortality from Breast Carcinoma Among US Women: The Role and Implications of Socio-Economics, Heterogeneous Insurance, Screening Mammography, and Geography. Health Care Management Science 6, 237–248 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026281608207

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026281608207