Abstract

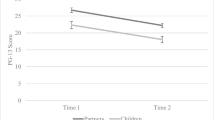

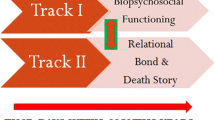

Previous studies have associated emotion and appraisal with long-term bereavement outcome. The present study extended this research by coding conjugal bereavement narratives for core relational themes (CRT) that served as emotional summaries of unique combinations of appraisal features. A range of CRTs was evidenced at 6 months after loss, with positive CRTs, such as love/affection and pride, occurring most frequently. As a way to examine competing models of coping with loss, CRTs were grouped by goal-congruence (positive/negative) and appraisal features (self/interpersonal) into four thematic categories, and they were compared with 6-, 14-, and 25-month outcome. Results contradicted the traditional “grief work” perspective, but they were consistent with the alternative view that recovery is fostered by identity continuity and a continued emotional bond with the deceased. With initial symptoms and Dyadic Adjustment Scale scores controlled, enhanced self themes (e.g., self-pride) and interpersonal affirmation themes (e.g., pride in the deceased) were each associated with improved functioning over time, whereas interpersonal discord themes (e.g., anger at the deceased) were associated with chronic grief.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Averill, J. R., & Nunley, E. P. (1993). Grief as an emotion and as a disease: A social-constructionist perspective. In M. S. Stroebe, W. Stroebe, & R. O. Hansson (Eds.), Handbook of bereavement: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 367–380). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1987). Manual for the Beck depression inventory. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovitch.

Belitsky, R., & Jacobs, S. (1986). Bereavement, attachment theory, and mental disorders. Psychiatric Annals, 16, 276–280.

Bonanno, G. A. (1997). Examining the “grief work” approach to bereavement. Paper presented at the 5th International Conference on Grief and Bereavement, Washington, DC.

Bonanno, G. A. (1998). The concept of “working through” loss: A critical evaluation of the cultural, historical, and empirical evidence. In A. Maercker, M. Schuetzwohl, & Z. Solomon (Eds.), Post-traumatic stress disorder: Vulnerability and resilience in the life-span. Seattle: Hogrefe & Huber.

Bonanno, G. A., & Kaltman, S. (in press). Toward an integrative perspective on bereavement. Psychological Bulletin.

Bonanno, G. A., & Keltner, D. (1997). Facial expressions of emotion and the course of conjugal bereavement. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 126–137.

Bonanno, G. A., Keltner, D., Holen, A., & Horowitz, M. J. (1995). When avoiding unpleasant emotions might not be such a bad thing: Verbal-autonomic response dissociation and midlife conjugal bereavement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 975–989.

Bonanno, G. A., Notarius, C. I., Gunzerath, L., Keltner, D., & Horowitz, M. J. (1998). Interpersonal ambivalence, perceived dyadic adjustment, and conjugal loss. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 1012–1022.

Bonanno, G. A., Znoj, H. J., Siddique, H., & Horowitz, M. J. (in press). Verbal-autonomic response dissociation and adaptation to midlife conjugal loss: A follow-up at 25 months. Cognitive Therapy and Research.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Loss: Sadness and depression: Volume 3, Attachment and loss. New York: Basic Books.

Brook, R. H., Ware, J. E., Davies-Avery, A., Stewart, A. L., Donald, C. A., Rogers, W. H., Williams, K. N., & Johnson, J. A. (1979). Overview of adult health status measures fielded in Rand's Health Insurance Study. Medical Care, 17, 1–119.

Butterworth, B. (1975). Hesitation and semantic planning in speech. Journal of Psycholinquistic Research, 4, 75–87.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1981). Attention and self-regulation: A control theory approach to human behavior. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Cerney, M. W., & Buskirk, J. R. (1991). Anger: The hidden part of grief. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 55, 228–237.

Deutsch, H. (1937). Absence of grief. Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 6, 12–22.

Ekman, P. (1993). Facial expression and emotion. American Psychologist, 48, 384–392.

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1986). A new pan-cultural facial expression of emotion. Motivation and Emotion, 10, 159–168.

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1988). Who knows what about contempt: A reply to Izard and Haynes. Motivation and Emotion, 12, 17–22.

Faschingbauer, T. R. (1981). The Texas Revised Inventory of Grief manual. Houston, TX: Honeycomb.

Field, N. P., Bonanno, G. A., Williams, P., & Horowitz, M. J. (in press). Applying of blame in conjugal loss. Cognitive Therapy and Research.

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1988). Coping as a mediator of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 468–473.

Fraley R. C., & Shaver, P. R. (1999). Loss and bereavement: Bowlby's theory and recent controversies concerning grief work and the nature of detachment. In J. Cassidy & P.R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment theory and research: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 735–759). New York: Guilford.

Freud, S. (1917/1957). Mourning and melancholia. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 14, pp. 152–170). London: Hogarth Press.

Frijda, N. H. (1986). The emotions. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Frijda, N. H. (1993). The place of appraisal in emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 7, 357–387.

Hansson, R. O., Carpenter, B. N., & Fairchild, S. K. (1993). Measurement issues in bereavement. In M. S. Stroebe, W. Stroebe, & R. O. Hansson (Eds.), Handbook of bereavement: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 62–76). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Hansson, R. O., Remondet, J. H., & Galusha, M. (1993). Old age and widowhood: Issues of personal control and independence. In. M. S. Stroebe, W. Stroebe, & R. O. Hansson (Eds.), Handbook of bereavement: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 367–380). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Holmes, T., & Rahe, R. (1967). The social readjustment scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11, 213–218.

Horowitz, M. J., Wilner, N., & Alvarez, M. A. (1979). Impact of event scale: A measure of subjective distress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 41, 209–218.

Horowitz, M. J., Bonanno, G. A., & Holen, A. (1993). Pathological grief: Diagnosis and explanations. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55, 260–273.

Kastenbaum, R. J. (1995). Death, society, and human experience (5th ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Keltner, D., & Bonanno, G. A. (1997). A study of laughter and dissociation: Distinct correlates of laughter and smiling during bereavement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 687–702.

Klas, D., Silverman, P. R., Nickman, S. L. (Eds.). (1996). Continuing bonds: New understandings of grief. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis.

Lazare, A. (1989). Bereavement and unresolved grief. In A. Lazare (Ed.), Outpatient psychiatry: Diagnosis and treatment (2nd ed., pp. 381–397). Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins.

Lazarus, R. S. (1984). On the primacy of cognition. American Psychologist, 39, 124–129.

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

Lazarus, R. S., Kanner, A. D., & Folkman, S. (1980). Emotions: A cognitive-phenomenological analysis. In R. Plutchik & H. Kellerman (Eds.), Emotions: Theory, Research, and Experience (Vol. 1, pp. 189–217). New York: Academic Press.

LeDoux, J. (1989). Cognitive-emotional interactions in the brain. Cognition and Emotion, 3, 267–289.

Lehman, D. R., Wortman, C. B., & Williams, A. F. (1987). Long-term effects of losing a spouse or child in a motor vehicle crash. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 218–231.

Leventhal, H. (1984). A perceptual-motor theory of emotion. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 17, 117–182.

Lindemann, E. (1994). Symptomatology and management of acute grief. American Journal of Psychiatry, 101, 141–148.

Lundin, T. (1984). Long-term outcome of bereavement. British Journal of Psychiatry, 145, 434–428.

Marmot, M. G., Smith, G. D., Stansfeld, S., Patel, C., North, F., Head, J., White, I., Brunner, E., & Feeney, A. (1991). Health inequalities among British civil servants: The Whitehall II Study. Lancet, 337, 1387–1393.

Mergenthaler, E., & Stinson, C. H. (1992). Psychotherapy transcription standards. Psychotherapy Research, 2, 125–142.

Mossey, J. M., & Shapiro, E. (1982). Self-rated health: A predictor of mortality among the elderly. American Journal of Public Health, 72, 274–279.

Nolen-Hoesksema, S., mcBride, A., & Larson, J. (1997). Rumination and psychological distress among bereaved partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 855–862.

Oatley, K., & Jenkins, J. M. (1996). Understanding emotions. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Opoku, K. A. (1989). African perspectives on death and dying. In A. Berger, P. Badham, A. H. Kutscher, J. Berger, M. Perry, & J. Beloff (Eds.), Perspectives on death and dying (pp. 14–23). Philadelphia, PA: The Charles Press.

Osterweis, M., Solomon, F., & Green, F. (Eds.). (1984). Bereavement: Reactions, consequences, and care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Parkes, C. M., & Weiss, R. S. (1983). Recovery from bereavement. New York: Basic Books.

Pennebaker, J. W., Mayne, T.J., & Francis, M.E. (1997). Linguistic predictors of adaptive bereavement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 863–871.

Raphael, B. (1983). The anatomy of bereavement. New York: Basic Books.

Raphael, B., Middleton, W., Martinek, N., & Misso, V. (1993). Counseling and therapy of the bereaved. In M. S. Stroebe, W. Stroebe, & R. O. Hansson (Eds.), Handbook of bereavement: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 23–43). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Rosenblatt, P. C. (1993). Grief: The social context of private feelings. In M. S. Stroebe, W. Stroebe, & R. O. Hansson (Eds.), Handbook of bereavement: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 102–111). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Roseman, I. J., Antoniou, A. A., & Jose, P. E. (1996). Appraisal determinants of emotion: Constructing a more accurate and comprehensive theory. Cognition and Emotion, 10, 241–277.

Sanders, C. M. (1979). The use of the MMPI in assessing bereavement outcome. In C. S. Newmark (Ed.), MMPI: Clinical and research trends (pp. 223–247). New York: Praeger.

Sanders, C. M. (1993). Risk factors in bereavement outcome. In M. S. Stroebe, W. Stroebe, & R. O. Hansson (Eds.), Handbook of bereavement: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 255–267). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1988). A model of behavioral self-regulation: Translating intention into action. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in the experimental study of social psychology (Vol. 21, pp. 303–346). New York: Academic Press.

Scherer, K. R. (1993). Studying the emotion-antecedent appraisal process: An expert system approach. Cognition and Emotion, 7, 325–355.

Shaver, P., Schwartz, J., Kirson, D., & O'Connor, C. (1987). Emotion knowledge: Further exploration of a prototype approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 1061–1086.

Shuchter, S. R., & Zisook, S. (1993). The course of normal grief. In M. S. Stroebe, W. Stroebe, & R. O. Hansson (Eds.), Handbook of bereavement: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 23–43). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Silverman, P. R., & Worden, W. (1993). Children's reactions to the death of a parent. In M. S. Stroebe, W. Stroebe, & R. O. Hansson (Eds.), Handbook of bereavement: Theory research, and intervention (pp. 300–316). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, C. A., & Ellsworth, P. C. (1985). Patterns of cognitive appraisal in emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 813–848.

Smith, C. A., & Lazarus, R. S. (1993). Appraisal components, core relational themes, and the emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 7, 223–269.

Spanier, G. B. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 38, 15–28.

Stansfeld, S. A., Smith, G. D., & Marmot, M. (1993). Association between physical and psychological morbidity in Whitehall II Study. Unpublished manuscript. University College of Middlesex Hospital School of Medicine, London.

Stinson, C. H., Milbrath, C., Reidbord, S. P., & Bucci, W. (1994). Thematic segmentation of psychotherapy transcripts for convergent analyses. Psychotherapy, 31, 36–48.

Stein, N. L., Folkman, S., Trabasso, T., & Christopher-Richards, A. (1977). Appraisal and goal processes as predictors of well-being in bereaved care-givers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 863–871.

Stroebe, M., Gergen, M. M., Gergen, K. J., & Stroebe, W. (1992). Broken hearts or broken bonds: Love and death in historical perspective. American Psychologist, 47, 1205–1212.

Stroebe, M., & Stroebe, W. (1991). Does “grief work” work? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59, 479–482.

Stroebe, W., & Stroebe, M. (1987). Bereavement and health: The psychological and physical consequences of partner loss. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Wikan, U. (1990). Managing turbulent hearts. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Windholz, M. J., Marmar, C. R., & Horowitz, M. J. (1985). A review of research on conjugal bereavement: Impact on health and efficacy of intervention. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 26, 433–447.

Zajonc, R. B. (1984). On the primacy of affect. American Psychologist, 39, 117–123.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bonanno, G.A., Mihalecz, M.C. & LeJeune, J.T. The Core Emotion Themes of Conjugal Loss. Motivation and Emotion 23, 175–201 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021398730909

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021398730909