Personalised nutrition (PN) is individualised dietary advice based on dietary habits, lifestyle, health status, phenotype and genotype( Reference Gibney and Walsh 1 , Reference Hesketh 2 ), and focuses on health promotion( Reference Gibney and Walsh 1 ). In contrast to generic dietary health recommendations, PN is based on an individual’s phenotype, genotype or a combination of these, tailored to individual lifestyle needs, and can be offered ‘direct-to-consumer’( Reference Covolo, Rubinelli and Ceretti 3 ). The public has positive attitudes towards PN, perceiving advantages regarding health, body weight and fitness( Reference Poínhos, van der Lans and Rankin 4 , Reference Stewart-Knox, Rankin and Kuznesof 5 ) and taking control of one’s health( Reference Rankin, Kuznesof and Frewer 6 ). According to the Theory of Planned Behaviour( Reference Ajzen 7 ), attitudes are among the most important factors determining intentions to execute behaviours. Positive attitudes towards PN are a strong predictor of intended uptake( Reference Poínhos, van der Lans and Rankin 4 , Reference Stewart-Knox, Bunting and Gilpin 8 ). Determinants of food choice, particularly those which motivate specific decisions, are likely to be reflected in attitudes towards and intention to adopt PN( Reference Ronteltap, van Trijp and Renes 9 ).

Food choices are determined by a multitude of individual, social and environmental factors( Reference Baudry, Peneau and Alles 10 , Reference Kearney, Kearney, Dunne and Gibney 11 ). The Food Choice Questionnaire (FCQ)( Reference Steptoe, Pollard and Wardle 12 ) focuses on individual determinants of food choice and assesses the importance of nine possibly interrelated motivating factors, some linked to health. The nine-factor FCQ has been validated in a number of different European countries( Reference Markovina, Stewart-Knox and Rankin 13 – Reference Prescott, Young and O’Neill 18 ). Motives for food choice, assessed using the FCQ, correlate with willingness to consume sustainable foods( Reference Dowd and Burke 19 ), GM foods( Reference Chen 20 ), functional foods( Reference Ares and Gambaro 21 ), organic foods( Reference Chen 22 , Reference Honkanen, Verplanken and Olsen 23 ), vegetarian( Reference Pollard, Steptoe and Wardle 24 ) and traditional( Reference Pieniak, Perez-Cueto and Verbeke 25 , Reference Pieniak, Verbeke and Vanhonacker 26 ) foods.

Poínhos et al. ( Reference Poínhos, van der Lans and Rankin 4 ) sought to explain attitudes towards and uptake of PN with reference to psychological traits associated with health behaviour change. Perceived benefit, high internal health locus of control and nutrition self-efficacy determined attitudes and intention to adopt PN( Reference Poínhos, van der Lans and Rankin 4 ). This previous research( Reference Poínhos, van der Lans and Rankin 4 ) also indicated that attitudes towards PN will be related to intention. The current analysis, therefore, while not making further inferences on attitude and intention to adopt PN, has included all indirect as well as direct effects, and has focused on identification of salient motives for choosing foods and how they relate to attitudes and intention towards PN. To our knowledge, no research to date has considered food choice motives in relation to dietary health-promoting technologies. Understanding the perceived importance of specific food choice motivations in relation to attitudes and behavioural intentions to adopt PN is necessary for the development of effective communication strategies and/or advice in keeping with an individual’s thinking around food.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses

The FCQ( Reference Steptoe, Pollard and Wardle 12 ) comprises nine factors which have been demonstrated to motivate food choices: health, weight control, ethical concern, price, sensory appeal, mood, convenience, natural content and familiarity. Previous research using the FCQ has corroborated the relationship between health as a motivation for food choice and dietary health behaviours( Reference Steptoe, Pollard and Wardle 12 , Reference Sun 27 , Reference Verbeke 28 ). Motivation to improve health is a driver of adoption of new dietary health promotion technologies( Reference Poínhos, van der Lans and Rankin 4 , Reference Stewart-Knox, Rankin and Kuznesof 5 , Reference de Roos 29 , Reference Stewart-Knox, Kuznesof and Robinson 30 ). Individuals highly motivated in their food choices by the desire to improve and maintain ‘health’ may be expected to have positive attitudes towards, and be more likely to adopt, PN. PN may be adopted for a range of different reasons including, inter alia, weight control and disease prevention. Communication, therefore, will need to address different motives for adoption and in doing so could potentially address individual motives for food choice in tailoring advice.

Weight control is a factor determining attitudes and intention to adopt PN( Reference Stewart-Knox, Kuznesof and Robinson 30 ) and has been found to be the most important factor determining food choice in Germany, Spain, Greece and Ireland( Reference Markovina, Stewart-Knox and Rankin 13 ). Given that higher scores on weight control (FCQ) have been found to be associated with maintenance of healthy eating regimens( Reference Pollard, Greenwood and Kirk 31 ), it is expected to be positively related to attitude and intention to adopt PN( Reference Dressler and Smith 32 ). Those for whom optimal body weight is an important motive for food choice are predicted to have more positive attitudes towards and greater intention to adopt PN.

Concern about the ethics of food (i.e. country of origin and environmental aspects of packaging) has been associated with greater fruit and vegetable consumption( Reference Honkanen, Verplanken and Olsen 23 ) and vegetarianism( Reference Pollard, Steptoe and Wardle 24 ). Assuming the general public is likely to associate personalised diets with the promotion of more healthy foods, ethical concern is therefore predicted to relate to positive attitudes and intention to adopt PN.

Food prices are another determinant of food choice, particularly for those on low incomes( Reference Lee, Ralston and Truby 33 , Reference Steenhuis, Waterlander and de Mul 34 ). Price was reported to represent a barrier to healthy food choice for 15 % of a nationally representative sample from across fifteen EU member states( Reference Steenhuis, Waterlander and de Mul 34 , Reference Lappalainen, Kearney and Gibney 35 ). The FCQ motive ‘price’ has been associated with less frequent purchasing of healthier foods( Reference Baudry, Peneau and Alles 10 , Reference Steptoe, Pollard and Wardle 12 , Reference Pollard, Steptoe and Wardle 24 ). Previous research into factors determining adoption of PN has suggested price is an important consideration for some consumers( Reference Lappalainen, Saba and Holm 36 ), and the general public may not accept PN at a higher cost than conventional nutrition programmes( Reference Fischer, Berezowska and van der Lans 37 ). Those for whom price is an important motivation for food choice, therefore, could be expected to hold more negative attitudes towards PN and be less likely to adopt it( Reference Fischer, Berezowska and van der Lans 37 ), if they also perceive that healthy foods and recommended diets will be more expensive( Reference di Santis, Grier and Oakes 38 , Reference Waterlander, de Boer and Schuit 39 ).

Sensory appeal is an important determinant of food preference( Reference Wang, de Steur and Gellynck 40 ) and choice( Reference Stewart-Knox, Rankin and Kuznesof 5 , Reference Prescott, Young and O’Neill 18 ), and for many consumers is more important than health in making food choice decisions( Reference Baudry, Peneau and Alles 10 , Reference Hebden, Chan and Louie 41 , Reference Carrillo, Varela and Salvador 42 ). The perception that the sensory attributes of healthier foods are less appealing is potentially detrimental to the purchasing of healthy and functional foods( Reference Ares and Gambaro 21 , Reference Verbeke 28 ). Personalised nutritional advice may recommend foods based on health and functional benefits rather than on taste, thus the general public may expect personalised diets to contain less appealing foods. Those for whom sensory appeal is an important motivation for food choice are expected to hold less positive attitudes towards and less intention to adopt PN.

Previous research has suggested that food choices can be used to influence mood (i.e. coping with stress, enhancing alertness or relaxing)( Reference Koster and Mojet 43 – Reference Williams, Stewart-Knox and Rowland 46 ). Conversely, foods consumed have been shown to influence one’s mood( Reference Williams, Stewart-Knox and Rowland 46 ). Given that mood has been shown to be a determinant of both healthy and less healthy food choices( Reference Williams, Stewart-Knox and Rowland 46 , Reference Yegiyan and Bailey 47 ), it is difficult to predict if the food choice motive ‘mood’ will be positively or negatively associated with attitudes towards and intention to adopt PN.

Convenience is an important determinant of food choice( Reference Baudry, Peneau and Alles 10 , Reference Machin, Gimenez and Vidal 48 ), so likewise adoption of PN will depend upon perceived convenience( Reference Ronteltap, van Trijp and Renes 9 ). Since the food choice motive ‘convenience’ is a driver of unhealthy food choices( Reference Chambers, Lobb and Butler 49 ) and given that healthy food offered as part of PN could be perceived as inconvenient suggests that those for whom convenience is an important motivation for food choice may hold less favourable attitudes towards PN and be less inclined to adopt it.

Perceptions that a food is ‘natural’ may motivate some consumers to consider it in specific food choices( Reference Pollard, Greenwood and Kirk 31 , Reference Teratanavat and Hooker 50 ). Perceptions of ‘naturalness’ are associated with the degree to which foods are perceived to have been processed (including the use of additives and artificial ingredients), with food that has undergone greater processing considered less natural( Reference Rozin 51 ). Personalised diets could be expected to encompass functional foods bearing health claims to meet specific individual dietary health needs. Functional food products bearing health claims, if highly processed, are considered less natural( Reference Lahteenmaki, Lampila and Grunert 52 ). Some individuals for whom ‘natural content’ is an important motive for food choice report lower consumption of functional foods( Reference Ares and Gambaro 21 , Reference Verbeke 28 ). Personalised diets, however, would be adjusted to accommodate a preference for natural foods. ‘Natural content’, therefore, is expected to be related to attitudes towards and intention to adopt PN, although the direction of the association is difficult to determine.

Many people prefer and choose foods that are familiar( Reference Hoek, Pearson and James 53 ) and familiarity tends to be associated with tradition( Reference Pieniak, Perez-Cueto and Verbeke 25 , Reference Kooijmans and Flores-Palacios 54 , Reference Giacalone and Jaeger 55 ). PN may not be adopted if advice deviates from the usual diets of the users( Reference Ronteltap, van Trijp and Renes 9 , Reference Bouwman, Koelen and Hiddink 56 ). This is further impacted if individuals find it difficult to adhere to nutritional advice if recommended foods( Reference Giacalone and Jaeger 55 , Reference Brecic, Gorton and Barjolle 57 ) and brands( Reference Bimbo, Bonanno and Nocella 58 ) are unfamiliar. There may be the expectation among potential consumers that recommended foods may not always be familiar to them. It is predicted, therefore, that those for whom familiarity is an important determinant of food choice will hold more negative attitudes and intention towards PN.

In summary, it is hypothesised that people for whom price, sensory appeal, convenience and familiarity are important drivers of food choice will hold less favourable attitudes to PN and have less intention to adopt it. Those for whom health body weight and natural content are important motivators of food choice are expected to hold favourable attitudes and intentions to adopt PN. Mood will be associated attitudes and/or intention towards PN, although the direction is difficult to predict.

Methods

Ethical approval for the present online survey was granted by Newcastle University Research Ethics Committee. Data collection was part of a larger survey on PN. The questionnaire was administered (n 9381) during February and March 2013. Participants were recruited through research agencies in nine European countries (Germany, Greece, Ireland, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Netherlands, UK and Norway) in each country’s national language using quotas stratified to be representative of their country population in terms of age and sex. There were no exclusion or inclusion criteria, although given the survey was online, all were computer literate. There was a 31·9 % response rate. The resultant sample was 50·6 % male, of whom 22·0 % were aged 18–29 years; 23·4 % were aged 30–39 years; 34·8 % were aged 40–54 years; and 19·8 % were aged 55–65 years. Using the International Standard Classification of Education Level, 28·7 % were classified as low, 38·9 % as middle and 32·4 % as highly educated. A detailed account of the development of the online survey tool, sampling and procedure has been given previously( Reference Poínhos, van der Lans and Rankin 4 ).

Measures

PN was defined at commencement of the survey as ‘healthy eating advice that is tailored to suit an individual based on their own personal health status, diet, physical activity and/or genetics’.

Food Choice Questionnaire

The FCQ( Reference Markovina, Stewart-Knox and Rankin 13 ) comprises nine factors. Each factor is measured by multiple items asking respondents to rate the importance they attach to motives for choosing food. Responses were on a 5-point rating scale from 1=‘not at all important’ to 5=‘extremely important’. For a full list of items see the online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1. The validation of the FCQ for the present study purpose is described in Markovina et al. ( Reference Markovina, Stewart-Knox and Rankin 13 ).

Attitude towards personalised nutrition

Attitude towards PN was measured on four individual, semantic, differential 5-point rating scales adapted from Crites et al. ( Reference Crites, Fabrigar and Petty 59 ), with responses to the statement ‘PN is …’ ranging from ‘very worthless’ to ‘very valuable’; ‘very unpleasant’ to ‘very pleasant’; ‘very boring’ to ‘very interesting’; and ‘very bad’ to ‘very good’. For validation of this scale in the current data set, refer to Poínhos et al. ( Reference Poínhos, van der Lans and Rankin 4 ).

Intention to adopt personalised nutrition

The items measuring intention to adopt PN were adapted from Melnyk et al.’s( Reference Melnyk, Herpen and Fischer 60 ) behavioural intention scale, in turn adapted from Oliver et al.’s( Reference Oliver, Rust and Varki 61 ) intention scale. Specific items were adapted for intention to adopt PN. Respondents were asked to ‘Please indicate the extent you agree or disagree with the following statements’: ‘I intend to adopt PN’; ‘I would consider adopting PN’; and ‘I am definitely going to adopt PN’. Responses were on a 5-point Likert scale ranging 1=‘completely disagree’ to 5=‘completely agree’. Validation of this scale in the current data set has been reported in Poínhos et al. ( Reference Poínhos, van der Lans and Rankin 4 ).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using the statistical software packages IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 22.0 and MPlus version 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2011). Multigroup confirmatory factor analysis and multigroup structural equation modelling were conducted across the nine EU countries to assess: attitude towards PN; intention to adopt PN; and food choice motives. This enabled assessment of the measurement model for each individual construct. Validity and reliability of the food choice motives in nine European countries have been reported in Markovina et al.( Reference Markovina, Stewart-Knox and Rankin 13 ). Direct causal and indirect relationships between the latent constructs were tested using multigroup structural equation modelling.

Confirmatory factor analyses

Two multigroup one-factor models were constructed with country of residence as group. The first focused on attitude towards PN, the second on intention to adopt PN. The food choice motives were analysed in one combined multigroup nine-factor model. Metric and scalar measurement invariance( Reference Steenkamp and Ter Hofstede 62 , Reference Steenkamp and Baumgartner 63 ) were tested in a step-wise process. Modifications (e.g. relaxing the equalities on country-specific factor loadings or intercepts) were added to the model, based on large modification indices, until model fit indices were acceptable. The factor ‘ethical concern’ was compiled of three items, including ‘comes from countries I approve of politically’, which had a lower factor loading (0·584) than the other items and a lower correlation with the other two ethical concern items. This item was allowed to deviate from equality constraints (on the item intercept) in the measurement part of the model. Model fit indices presented include Satorra–Bentler corrected χ 2 (SB χ 2), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardised root-mean-square residual (SRMR), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) and comparative fit index (CFI). Values <0·07 for RMSEA, <0·08 for SRMR and >0·95 for TLI and CFI suggest an acceptable model fit( Reference Hair, Black and Babin 64 , Reference Hu and Bentler 65 ).

Structural equation model

To detect differences between countries, a multigroup structural equation model was performed in six steps that consecutively added cross-country equality constraints. The structure of the model was tested through configural invariance (Model I), metric invariance (Models II and III) and scalar invariance (Models IV, V and VI). For each model, the following modifications were added: in Model I, path coefficients between latent constructs were allowed to vary across countries; in Model II, path coefficients between latent constructs were held equal (i.e. not allowed to vary across countries); in Model III, variances and covariances among exogenous latent constructs (FCQ items) were held equal; in Model IV, regression intercepts for attitude towards PN and intention to adopt PN were held equal; in Model V, means for the nine exogenous latent variables (FCQ) were held equal; and in Model VI, proportion of variance (R 2) in attitude towards PN and intention to adopt PN was held equal. A number of constraints were relaxed in the models, based on large modification indices, until model fit indices were acceptable. Model fit indices presented included SB χ 2, RMSEA, SRMR, TLI and CFI. Values <0·07 for RMSEA, <0·08 for SRMR and >0·95 for TLI and CFI suggest an acceptable model fit( Reference Hair, Black and Babin 64 , Reference Hu and Bentler 65 ).

Results

Sample description

A detailed description of the sample has been reported previously( Reference Poínhos, van der Lans and Rankin 4 ). A total of 29 450 individuals were contacted of whom 9381 volunteered and completed the online questionnaire, equating to a response rate of 31·9 %. The sample was 50·6 % male with a modal age of 40–54 years (34·8 %).

Aggregate mean (sd) attitude towards PN was 3·46 (0·67). Mean (sd) attitude towards PN for each country was: Poland, 3·64 (0·70); Portugal, 3·59 (0·62); Ireland, 3·58 (0·65); Spain, 3·56 (0·68); UK, 3·46 (0·70); Greece, 3·43 (0·61); Germany, 3·34 (0·69); Norway, 3·33 (0·74); Netherlands, 3·19 (0·54). Aggregate mean (sd) intention to adopt PN across countries was 2·98 (0·92). Mean (sd) intention to adopt PN for each country was: Poland, 3·23 (0·91); Spain, 3·2 (0·81); Greece, 3·18 (0·77); Portugal, 3·16 (0·77); Ireland, 3·16 (0·82); Germany, 2·96 (0·97); UK, 2·93 (0·89); Netherlands, 2·68 (0·82); Norway, 2·35 (1·07).

Confirmatory factor analyses

Consistent with previous analysis using this survey sample( Reference Poínhos, van der Lans and Rankin 4 ), single-factor models for attitude towards PN and intention to adopt PN were assumed. Metric invariance could be assumed for attitude towards PN across country, and partial metric invariance could be assumed for the food choice motives (FCQ scores) and intention to adopt PN across countries (Table 1). Partial scalar invariance held for all constructs when equality of item loadings or equality of item intercepts was relaxed in the case of large modification indices. Compared with recommended cut-off values, good model fit was demonstrated for all constructs in relation to SRMR. In relation to the model fit indices CFI and TLI, the FCQ scores and intention to adopt PN met the recommended cut-off values. Attitude towards PN was marginally below cut-off values (CFI=0·92, TLI=0·93). No cross-factor loadings were evident above the recommended cut-off of 0·4 in the FCQ nine-factor model. The FCQ scores met the criteria for optimal fit for RMSEA. The fit of the factor models for both attitude towards PN and intention to adopt PN was above the cut-off values. The measurement models developed in each of the three-factor models were then combined into a multifactor model. Compared with recommended cut-off values, model fit indices of this partial scalar model suggested good model fit (Table 1). That indicators of configural, metric and scalar invariance were satisfactory suggests that constructs had similar meaning for respondents from different countries and that any differences found in subsequent analyses have probably not been influenced by cultural or country-specific differences in measurements.

Table 1 Fit measures for factor models assessing food choice motives, attitude towards personalised nutrition (PN) and intention to adopt PN among nationally representative samples recruited in nine EU countriesFootnote † (n 9381), 2013

SB χ 2, Satorra–Bentler corrected χ 2; CFI, comparative fit index; TLI, Tucker–Lewis index; RMSEA, root-mean-square error of approximation; LB, lower bound; UB, upper bound; SRMR, standardised root-mean-square residual.

† Countries: Germany (GER), Greece (GRE), Ireland (IRE), Poland (POL), Portugal (POR), Spain (ES), the Netherlands (NL), the United Kingdom (UK) and Norway (NOR).

‡ Health: equality of item loading relaxed for 4th item in POL; equality of item intercepts relaxed for 1st item in GER, for 2nd item in ES, POL, UK and NL, for 3rd item in POL and POR, for 4th item in GER and NL, for 5th item in NOR and NL, and for 6th item in ES. Mood: equality of item loading relaxed for 4th item in POL; equality of item intercepts relaxed for 2nd item in ES and GRE, for 4th item in NOR, GER, ES, GRE, POL and POR, for 5th item in NOR, GER, GRE and POL, and for 6th item in NOR and GER. Convenience: equality of item intercepts relaxed for 2nd item in GRE, for 3rd item in NOR, GER, POL, UK and IRE, for 4th item in NOR, GER, ES, GRE, POL, NL and POR, and for 5th item in NOR, GRE, POL, NL and POR. Sensory appeal: equality of item loading relaxed for 4th item in ES; equality of item intercepts relaxed for 1st item in GRE and UK, for 2nd item in ES, NL and POR, for 3rd item in POR, and for 4th item in ES. Natural content: equality of item intercepts relaxed for 1st item in NOR and for 2nd item in GRE and POL. Price: equality of item loadings relaxed for 1st item in NOR and for 2nd item in ES; equality of item intercepts relaxed for 1st item in NOR, for 2nd item in NOR, ES, UK and IRE, and for 3rd item in GER. Weight control: equality of item loading relaxed for 1st item in NOR; equality of item intercepts relaxed for 1st item in NOR and GER, for 2nd item in NL, and for 3rd item in ES and POR. Familiarity: equality of item loading relaxed for 2nd item in GRE; equality of item intercepts relaxed for 1st item in NOR, GER, GRE, UK and IRE, for 2nd item in NOR, GRE and POR, and for 3rd item in POL and NL. Ethical concern: equality of item intercepts relaxed for 1st item in ES, GRE and UK, for 2nd item in UK, NL and POR, and for 3rd item in POL.

§ Equality of item intercept relaxed for 3rd item in NL.

║ Equality of item loading (and intercept) relaxed for 2nd item in ES; equality of item intercepts relaxed for 1st item in GRE, for 2nd item in NOR, GER and NL, and for 3rd item in GER.

Structural equation model

Compared with recommended cut-off values, the final partial scalar structural model (Model VI) showed good model fit when a number of means of the latent variable (FCQ) were allowed to deviate (Table 2). Standardised path coefficients in the structural equation for intention to adopt PN differed between countries proportional to differences in R 2, with the R 2 in Poland being closest to the mean R 2 (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 2). Given the large number of observations, the 0·01 level of significance has been assumed.

Table 2 Fit measures for multifactor model and structural equation models assessing food choice motives, attitude towards personalised nutrition (PN) and intention to adopt PN among nationally representative samples recruited in nine EU countriesFootnote † (n 9381), 2013

SB χ 2, Satorra–Bentler corrected χ 2; CFI, comparative fit index; TLI, Tucker–Lewis index; RMSEA, root-mean-square error of approximation; LB, lower bound; UB, upper bound; SRMR, standardised root-mean-square residual; R 2, proportion of variance.

† Countries: Germany (GER), Greece (GRE), Ireland (IRE), Poland (POL), Portugal (POR), Spain (ES), the Netherlands (NL), the United Kingdom (UK) and Norway (NOR).

‡ Relaxations on item loadings and intercepts adopted from measurement models (see Table 1).

§ Equality restriction relaxed for variance for price in NOR.

║ Equality restriction relaxed for regression intercept for intention in NOR and for attitude in NL.

¶ Equality restrictions relaxed for means of health in ES and POR; for mood in GRE, UK and NL; for convenience in GER, ES, GRE, POL and NL; for sensory appeal in GER, ES, UK and NL; for natural content in GRE, POL, UK, IRE and NL; for price in GRE and POR; for weight control in GER and NL; for familiarity in UK, IRE, NL and POR; and for ethical concern in GRE, NL and POR.

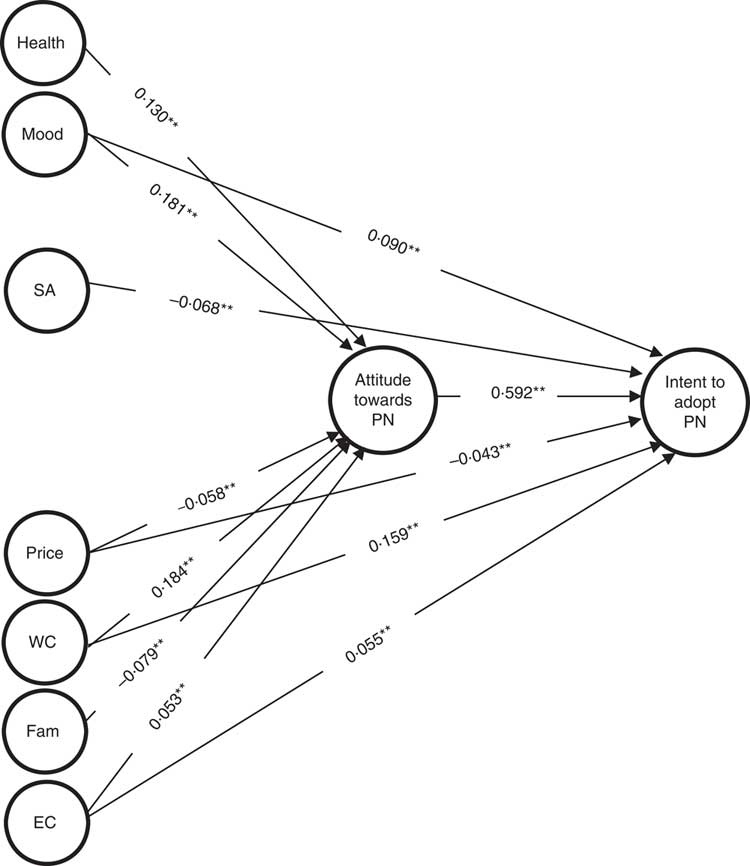

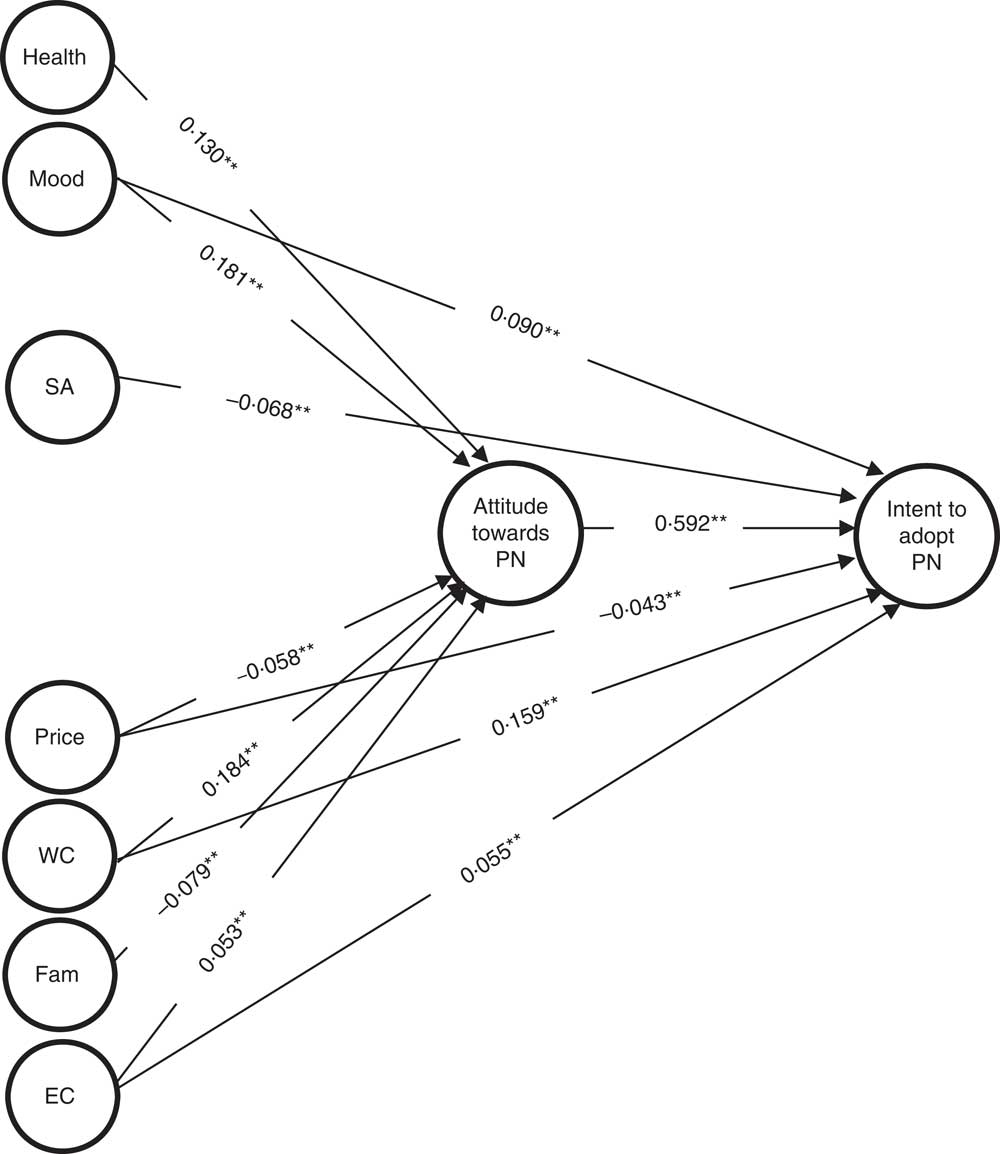

There was a strong positive association between attitude towards PN and intention to adopt PN (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Standardised path coefficients for direct associations of food choice motives with attitude towards personalised nutrition (PN) and intention to adopt PN (Model VI) in Poland. *P<0·01, **P<0·001 (SA, sensory appeal; WC, weight control; Fam, familiarity; EC, ethical concern)

Direct associations with attitude towards personalised nutrition

Taking the 0·01 level of significance, the food choice motives (FCQ) ‘weight control’ (estimate=0·184; se=0·017; P=0·000), ‘mood’ (estimate=0·181; se=0·029; P=0·000), ‘health (estimate=0·130; se=0·027; P=0·000) and, to a lesser degree, ‘ethical concern’ (estimate=0·053; se=0·017; P=0·002) were positively and directly related to attitude towards PN (Fig. 1). ‘Price’ (estimate=−0·058; se=0·017; P=0·001) and ‘familiarity’ (estimate=−0·079; se=0·018; P=0·000) were directly and negatively associated with attitude towards PN. There was no direct association between attitude towards PN and ‘natural content’ (estimate=0·039; se=0·018; P=0·037), ‘convenience’ (estimate=0·040; se=0·022; P=0·068) or ‘sensory appeal’ (estimate=0·007; se=0·002; P=0·726; Fig. 1).

Direct associations with intention to adopt personalised nutrition

Taking the 0·01 level of significance, the food choice motives (FCQ) ‘mood’ (estimate=0·090; se=0·024; P=0·000), ‘weight control’ (estimate=0·159; se=0·015; P=0·000) and ‘ethical concern’ (estimate=0·055; se=0·014; P=0·000) all had a significant direct positive association with intention to adopt PN. ‘Sensory appeal’ (estimate=−0·068; se=0·016; P=0·000) and ‘price’ (estimate=−0·043; se=0·014; P=0·003) had a significant direct negative association with intention to adopt PN. There was no direct association between intention to adopt PN and ‘health’ (estimate=0·030; se=0·022; P=0·175), ‘convenience’ (estimate=0·036; se=0·018; P=0·047), ‘natural content’ (estimate=−0·029; se=0·016; P=0·063) or ‘familiarity’ (estimate=0·004; se=0·015; P=0·795; Fig. 1).

Indirect associations with intention to adopt personalised nutrition

Taking the 0·01 level of significance, there were significant indirect positive associations via attitude between intention and the food choice motives (FCQ) ‘health’ (estimate=0·077; se=0·016; P=0·000), ‘mood’ (estimate=0·107; se=0·016; P=0·000), ‘weight control’ (estimate=0·109; se=0·010; P=0·000) and ‘ethical concern’ (estimate=0·031; se=0·010; P=0·002). There were significant indirect negative associations via attitude between intention and the food choice motives ‘price’ (estimate=−0·034; se=0·010; P=0·001) and ‘familiarity’ (estimate=−0·047; se=0·011; P=0·000). There was no indirect association between intention to adopt PN and ‘natural content’ (estimate=0·024; se=0·011; P=0·037), ‘convenience’ (estimate=0·024; se=0·013; P=0·068) or ‘sensory appeal’ (estimate=0·004; se=0·012; P=0·726).

All model-based internal consistency reliabilities( Reference Hu and Bentler 65 ) were above the 0·7 cut-off value( Reference Markovina, Stewart-Knox and Rankin 13 ), with all (except for ‘ethical concern’ in Greece) above 0·8. The proportion of variance (R 2) in attitude towards PN and intention to adopt PN was >0·350 in all countries (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 3).

Large positive correlations were observed between ‘health’ and ‘mood’ (r=0·797) and between ‘natural content’ and ‘ethical concern’ (r=0·649). More moderate correlations were observed between ‘mood’ and ‘sensory appeal’ (r=0·599), ‘weight control’ and ‘familiarity’ (r=0·595), ‘sensory appeal’ and ‘convenience’ (r=0·590), ‘mood’ and ‘natural content’ (r=0·573) and ‘health’ and ‘weight control’ (r=0·550; see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 4). High composite model-based internal consistency reliability reliabilities (>0·80) and large sample size (n 9381) should, however, have protected against any effect of multicollinearity( Reference Grewal, Cote and Baumgartner 66 ).

Discussion

The current analysis considered the degree to which attitude towards and intention to adopt PN are associated with motives for food choice, measured using the FCQ( Reference Steptoe, Pollard and Wardle 12 ). The questions we have asked are whether and in what way food choice motives are associated with attitude towards, and intention to adopt, PN. As would be predicted by the Theory of Planned Behaviour( Reference Ajzen 7 , Reference Conner and Sparks 67 ), the results suggest that individuals with more positive attitudes towards PN would be more likely to intend to adopt it. This is reflected in both direct and indirect (through attitude) associations between certain motives for food choice and attitude towards, and intention to adopt, PN (Fig. 1).

A number of studies utilising the FCQ have identified the desire to maintain and improve health as an important motive for food choice in various EU populations( Reference Markovina, Stewart-Knox and Rankin 13 , Reference Januszewska, Pieniak and Verbeke 15 , Reference Lindeman and Väänänen 68 ). Prior qualitative research conducted by the authors( Reference Stewart-Knox, Kuznesof and Robinson 30 ) indicated that the European public held favourable views on PN. It was hypothesised, therefore, that health as a food choice motive would be positively related to attitude and intention to adopt PN. As expected, those highly motivated by health were more likely to hold a positive attitude towards PN, exerting an indirect influence upon intended adoption. The health motivation, however, did not have a direct effect on intended adoption. This may be because, as suggested by qualitative research( Reference Rankin, Kuznesof and Frewer 6 , Reference Stewart-Knox, Kuznesof and Robinson 30 ), individuals for whom health concerns were an important motivation for food choice, despite holding positive attitudes towards PN, may already believe they eat a healthy diet and therefore do not consider that adoption of PN would provide benefits over and above their existing healthy eating habits. Another possible explanation is that in this sample health was only the fourth most important motivation for food choice after price, sensory appeal and natural content( Reference Markovina, Stewart-Knox and Rankin 13 ), implying that recommended foods would need to be affordable, tasty and natural before health benefits would be taken into account. The indirect effect on intention to adopt PN suggests that those for whom improving and maintaining health is an important driver of food choice may need to be convinced of the added health benefits of PN, so that these positive attitudes towards PN can be translated into adoption of PN.

As predicted, where weight control was an important motive for food choice, it was strongly directly associated with attitude towards PN, and both directly and indirectly (via attitude) associated with intention to adopt PN. This finding corroborates the results of the qualitative analysis conducted previously( Reference Stewart-Knox, Kuznesof and Robinson 30 ), which suggested that achieving weight loss was a potential motivator for engagement with PN. Weight control was correlated with health, suggesting that these constitute related motives for uptake of PN( Reference Stewart-Knox, Kuznesof and Robinson 30 ). Those for whom weight control was an important motive for food choice held more positive attitudes towards PN and indicated that they would be likely to adopt the service, implying that PN should target and aim to meet the needs of those seeking to control body weight. Weight control, however, was rated relatively low as the seventh most important motivation for food choice( Reference Markovina, Stewart-Knox and Rankin 13 ). That weight control was relatively important for food choice in Greece and Portugal( Reference Markovina, Stewart-Knox and Rankin 13 ) suggests that PN has greatest potential to help people control body weight in these countries.

Those who indicated that mood was an important motive for food choice were more likely to have a positive attitude towards, and (both directly and via attitude) report intention to adopt, PN. Mood and health motivations were strongly related and to a greater degree than other analyses of the FCQ have reported( Reference Steptoe, Pollard and Wardle 12 , Reference Pollard, Steptoe and Wardle 24 , Reference Pula, Parks and Ross 69 ). Our comparatively larger sample size suggests these results are probably more reliable. Mood and sensory appeal were also correlated, implying that seeking mood enhancement through the eating experience could be a potential motivator for, or deterrent to, adoption of PN. Meanwhile, those seeking to adopt PN may require foods and diets to match mood-driven preferences, suggesting that mood as a motive for food choice should be taken into account in the design of foods and diets. Mood is an important motive for food choice, should be considered when devising personalised dietary recommendations, and, if made prominent when promoting PN, could render attitudes and intention towards PN more positive.

As hypothesised, high scores on the ethical concern motive were positively related to attitude towards, and (both directly and via attitude) to intention to adopt, PN. Ethical concern was less strongly associated with attitude and intention compared with weight control, in line with other studies using the FCQ, where ethical concern was ranked one of the least important food choice motives( Reference Markovina, Stewart-Knox and Rankin 13 , Reference Januszewska, Pieniak and Verbeke 15 , Reference Prescott, Young and O’Neill 18 ). Here ethical concern appears important to those who have positive attitudes and intend to adopt PN. Method of production and related ethical issues should therefore be considered in nutritional advice provided under the auspices of a PN service.

As predicted, higher scores on price as a motive for food choice were associated with less favourable attitude towards, and (both directly and via attitude) with lower intention to adopt, PN. Research into food choice has suggested that monetary considerations are among the main reasons for not buying healthy foods( Reference Steptoe, Pollard and Wardle 12 , Reference Lappalainen, Kearney and Gibney 35 , Reference Lappalainen, Saba and Holm 36 ). The most important motivation for food choice in this sample was price( Reference Markovina, Stewart-Knox and Rankin 13 ). These data indicate only moderate associations between price, attitude and intention, reflecting existing qualitative research and that some consumers are willing to pay a premium for PN( Reference Stewart-Knox, Kuznesof and Robinson 30 ). The negative direct effect on intention to adopt PN suggests that individuals concerned with the price of food may perceive that they are unable to afford the foods needed to deliver PN, despite having a favourable attitude.

The food choice motive familiarity, as expected, was associated with more negative attitudes towards PN. To diminish the impact of familiarity, providers of PN should emphasise that individual advice will take existing dietary practices into account. Familiarity, despite the absence of a direct effect on intention to adopt PN, had an indirect effect on intention to adopt PN via attitude towards PN. This lack of direct effect in intention could be because whereas attitudes relate to others as well as oneself, intention is personal. Familiarity is also down to personal prior experiences. Familiarity items on the FCQ may have tapped into the perception that PN itself was unfamiliar, thereby influencing responses.

We hypothesised that convenience would be negatively associated with attitude towards, and intention to adopt, PN. Contrary to expectation, the present study’s results indicated that convenience was unrelated to attitude, and despite existing evidence suggesting that convenience may be important to uptake of PN( Reference Ronteltap, van Trijp and Renes 9 ), was unrelated to intention to adopt PN. That those who view PN favourably and intend to take it up do not rate convenience important to food choice suggests that personalised diets will not necessarily need to prioritise convenience.

It was hypothesised that those for whom sensory appeal was an important driver of food choice would have less favourable attitudes towards and be less likely to intend to adopt PN. There was no association between sensory appeal and attitude towards PN; however, those who were more highly motivated by sensory appeal had lower intention to adopt PN. The assumption that foods prescribed as part of a personalised plan may be selected on grounds other than sensory appeal may have impacted negatively on intention to adopt PN. Again, whereas attitudes could relate to the individual as well as others, intention is individual. Sensory appeal was the second most important motivation for food choice in this sample( Reference Markovina, Stewart-Knox and Rankin 13 ), suggesting that for PN services to be adopted, providers need to assure potential clients that diet plans will take their sensory preferences into account.

Natural content was ranked third most important food choice motive but was unrelated to attitude towards or intention to adopt PN. This contrasts with previous research implying that ‘natural content’ is associated with detrimental attitudes to highly processed foods such as GM( Reference Chen 20 ) and functional foods( Reference Ares and Gambaro 21 , Reference Verbeke 28 ), which could be expected to be a component of personalised diets. Those who hold positive attitudes towards and intend to adopt PN may be aware that natural foods such as fruit and vegetables may be recommended to provide functional benefits. Natural content was positively and strongly correlated with ethical concern, implying the motives are intertwined.

Study limitations

As with any self-reported data, there may have been response biases whereby respondents sought to project a socially desirable image in relation to their food choice motives( Reference Fisher 70 ). Added to this is the positive bias inherent in the FCQ such that the questionnaire may not have accurately captured the relative importance of each factor( Reference Steptoe, Pollard and Wardle 12 ). The established validity of the FCQ, however, suggests that this does not offer a major barrier to interpretation of the results. Results from the current analysis support the assumption of partial metric and indicate scalar measurement invariance( Reference Markovina, Stewart-Knox and Rankin 13 ), which is in line with studies that support the cross-cultural validity and use of the FCQ across Europe( Reference Januszewska, Pieniak and Verbeke 15 , Reference Pieniak, Verbeke and Vanhonacker 26 ). Another limitation of the FCQ is that it is focused on individual determinants of food choice to the neglect of social factors and the environment. It is also possible that since the questionnaire was translated into different languages, questions may have had subtly different meanings which may have contributed to differences between countries. Although well validated for the measurement of individual factors determining food choice( Reference Markovina, Stewart-Knox and Rankin 13 ), the FCQ might also benefit from some revision in the light of nutritional knowledge and current issues in food production. The ‘low fat’ item within the weight control factor, for example, could consider the type of fat and the ethical factor could include an item on animal welfare. The cross-sectional nature of the survey limits the ability to draw information on causality( Reference Carlson and Morrison 71 ). In addition, because the survey was conducted via the Internet, the sample was biased towards those who are more computer literate and spend time online. Individuals who have computers at home are likely to be more affluent and may prioritise food choice motives differently. PN in the Food4me project is (in part) a digital offering, which renders the sample appropriate to answer our research question on food choice motives, attitude and intention towards PN. Further research is needed to consider the needs of more disadvantaged societal groups and how to serve them through PN( Reference Stewart-Knox, Markovina and Rankin 72 ). Another potential limitation is that because panellists were quota sampled and then stratified to be representative of their country population in terms of age and sex, it has not been possible to determine if those who responded differed demographically from those who did not. There was between-country variation in attitude towards and intention to adopt PN which could have affected the results. Attitude was most positive and intention to adopt PN highest in Poland, implying potential for PN in Poland. Despite an operational definition of PN having been provided at the beginning of the survey questionnaire, lack of direct experience with PN may explain the moderate response rate (31·9 %). The low number of partially completed questionnaires (4·0 %) suggests that those who did respond fully understood the concept and the questions. A lack of direct experience with PN services was expected across the sample, since the technology was still in its infancy at the time the study was conducted, and the dependent variable was intended adoption, rather than actual behaviour (i.e. actual uptake of the service). The association between intended adoption and actual behaviour may require further analysis. Future research may need to consider actual users of this novel technology to ascertain the potential for food choice motives to act as motivators and barriers to adoption and compliance with PN interventions.

Conclusion

The present results provide insights into how motivators of food choice relate to attitude towards PN and intention to adopt it, in nine European countries. People who differ in the importance they attribute to the various food choice motives may have different needs and will require varying approaches to the marketing and delivery of personalised recommendations. Those for whom weight control, ethical concern and mood were important motives for food choice exhibited more positive attitudes towards PN and reported that they were more likely to consider adopting the service. These factors need consideration in the design and implementation of individualised plans. Communication strategies to encourage adoption of PN should focus on how it can take account of food choice motives and convey the possibility of personalised plans to control body weight and enhance mood. While emphasising healthy content of recommended diets may instil positive attitudes towards PN, prioritising the sensory appeal of recommended foods should promote uptake. Determinants of food choices such as price and familiarity, associated with negative attitudes towards PN, may need to be taken into consideration when designing personal plans, so that PN advice is more likely to be followed. Reassurances should be provided that personalised plans will prescribe foods that are familiar to the individual and which routinely take sensory preferences as well as individual financial constraints into account.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The Food4Me project has been supported by the European Commission under the Food, Agriculture, Fisheries and Biotechnology Theme of the 7th Framework Programme for Research and Technological Development (grant number 265494). The European Commission had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: Funding was acquired by L.J.F., B.J.S.-K. and M.D.V.A. L.J.F., B.J.S.-K., A.R., R.P. and A.R.H.F. inputted to the final study design. L.J.F., S.K. and A.R.H.F. oversaw data collection. B.P.B., A.R. and B.J.S.-K. undertook the data analysis. B.P.B., A.R., I.A.v.d.L., J.M., R.P. and B.J.S.-K. contributed to the interpretation of data. B.J.S.-K. and A.R. drafted the manuscript. L.J.F., S.K., A.R., I.A.v.d.L., A.R.H.F., M.D.V.A., R.P., J.M. and B.J.S.-K. reviewed several re-drafts of the manuscript and checked the proof. Ethics of human subject participation: Ethical approval for the online survey was granted by Newcastle University Research Ethics Committee.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018001234