Abstract

This paper reports results of a numerical investigation on mixed convection heat transfer and entropy generation for water–copper nanofluid within a vertical channel. The left wall is subjected to a heat flux density of sinusoidal variation, while the right one is cooled at uniform density. The Buongiorno model is employed to describe the nanofluid flow in order to take into account the thermophoresis effect and the Brownian motion. The governing equations are solved numerically using the finite volume method with the SIMPLE algorithm. The effects of pertinent parameters including the Richardson number (Ri), the heat flux ratio (Rq) and the nanoparticles volume fraction (ϕi) on the flow and thermal fields, as well as the entropy generation are analyzed for both non-uniform and uniform heating. The results show that the heat transfer rate and the various irreversibility modes are increased with the rise of Ri and Rq and the reduction of ϕi. It is also found that a sinusoidal heating is beneficial for the mean Nusselt number but, unfortunately, it is not favorable for the total entropy generation with augmentation rates of up to 7% and 14%, respectively. A map of the flow reversal occurrence is performed and reveals that the latter is strongly affected by the control parameters. In addition, a correlation is proposed to predict the onset of this phenomena with a maximum deviation of 5% compared to the numerical results.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Nanofluids are mixtures of a base fluid (water, oil, ethylene glycol …) and nanoscale particles called nanoparticles (Cu, Al, Al2O3…). The advantage of these fluids lies in the fact that their thermal conductivity is greater than that of the conventional fluids and therefore significantly improves the heat transfer characteristics. In addition, owing the size of the nanoparticles (1–100 nm), the employment of nanofluids leads to very low pressure drop which makes them more attractive than the usual enhancement methods. However, to date, dispersion stability is considered as one of most challenging issues that limit the practical usage in industrial applications and further development of nanofluids. The most important parameters that affect this stability are the fluid temperature, as well as the nanoparticles size, concentration and distribution. To improve this stability, various methods have been used such as mechanical stirring, ultrasonic treatment, introducing surface charges or employing chemical surface modification with surfactants (e.g. oleic acid, citric acid, lauric acid). This will avoid aggregation and settling of nanoparticles due to Van der Waals forces and dipole–dipole interactions. A large amount of research work has been conducted on nanofluids over the past decade in order to highlight the benefits of their use. Han et al. [1] proposed a new type of complex nanoparticle (hybrid sphere/carbon nanotube) for applications in nanofluids. A MWCNT-Fe3O4/water hybrid nanofluid was prepared by Sundar et al. [2] to study the heat transfer and the friction factor for fully developed turbulent flow in a circular tube heated at constant heat flux. Arshad and Ali [3, 4] conducted an experimental study to characterize the heat transfer and the pressure drop of a TiO2–water nanofluid in a minichannel heat sink. On another work, the same authors [3, 4] examined the thermal and hydrodynamic performance of graphene nanoplatelets nanofluids on integral fin heat sink. Recently, Khan et al. [5] investigated and compared the energy and exergy performances of solar dish assisted s-CO2 Brayton cycle using three different thermal oil based nanofluids (Al2O3, CuO and TiO2). Numbers of review articles have also been published covering the methods of preparation, the characterization, the modeling and the application areas (e.g. [6,7,8,9]). They concluded that more research is required to simplify the methods of preparation of nanofluids in order to make them cost effective. Concerning the stability of nanofluids, they suggested to develop new mechanisms to avoid agglomeration and sedimentation.

Mixed convection in vertical channels is an important topic which has received considerable attention in the past and continues to attract researchers until now due to its relevance in many practical applications such as solar collectors, electronic equipment, nuclear reactors, heat exchangers, etc. In the recent years, many theoretical and experimental researches have been carried out to improve the heat exchange in these devices by using nanofluids. Fully-developed nanofluids flow and heat transfer in vertical channels were performed both analytically and numerically by Xu and Pop [10] and Fakour et al. [11]. The authors noticed that the addition of nanoparticles enhances significantly the performance of such systems. A modified Buongiorno’s model was used by Malvandi and Ganji [12] for a water–Al2O3 nanofluid to take into account nanoparticles migration occurring in a vertical microchannel. The results indicated an improvement of the heat transfer rate by the increase of the parameters related to mixed convection, slip condition and volume fraction of nanoparticles. An opposite effect of these parameters is found for the pressure drop. The same authors, considered in another work [13] the impact of a magnetic field and concluded that the latter has a negative effect on the performance of the system. A similar study to the two previous ones [12, 13] was undertaken by Hedayati and Domairry [14]. The results revealed that the direction of the nanoparticles migration is affected by the asymmetric thermal boundary conditions employed in this research work. Nanoparticles migration has also been investigated by Malvandi et al. [15] by considering the impact of temperature-dependence thermophysical properties. In another work (Malvandi et al. [16]), these authors employed the modified two-component heterogeneous model of Buongiorno to resolve a similar problem than Malvandi and Ganji [15] in presence of heat source/sink with the microchannel walls heated at uniform but different heat fluxes. They found that the optimal improvement is reached at high slip velocities and for the case of one- sided heating. The impact of a uniform and transverse magnetic field on nanofluids flow and heat transfer characteristics in a vertical channel was studied by Das et al. [17]. They highlighted the dependence of the onset of flow instability on nanoparticles volume fraction and magnetic field intensity. Li et al. [18] treated the problem of mixed convection in a vertical channel filled with two immiscible layers; one is a non-Newtonian nanofluid and the other a Newtonian fluid. The analysis of the results mainly focused on the effect of the power-law index on the flow and heat transfer characteristics. The behavior of magnetohydrodynamic nanofluids in vertical microtubes was considered by Moshizi et al. [19] by taking into account the Brownian motion and the thermophoresis effect. They obtained an improvement of the thermal performance by increasing the magnetic field intensity and the slip velocity at the fluid–solid interface. The objective of the research work undertaken by Hosseini et al. [20] was to explain how nanoparticles motion can tune the thermal performance and heat transfer rate in microtubes filled with alumina/water nanofluid.

A method for evaluating the performance of a system consists on the analysis of entropy generation based on the second law of thermodynamics. In heat transfer processes different sources of irreversibility can be responsible for entropy generation: temperature gradients, viscous effect, magnetohydrodynamic effect, etc. Studies on entropy generation using nanofluids are mainly focused on differentially heated enclosures [21,22,23,24,25]. However, those related to horizontal and vertical channels are limited especially under mixed convection regime. Entropy generation analysis in presence of a transverse magnetic field was numerically performed by Hajialigol et al. [26] inside a horizontal three-dimensional microchannel with alumina/water nanofluid as the work fluid. By increasing the strength of the imposed magnetic field, their results revealed a diminution of the entropy generation due to heat transfer and an augmentation of the fluid friction and magnetic irreversibilities. Mixed convection heat transfer and entropy generation of Al2O3–water nanofluid in a vertical channel were investigated by Chen et al. [27]. They found that in the regions adjacent to the walls, the entropy generation due to fluid friction is dominant, whereas in the central region of the channel, it is the thermal irreversibility that dominates. In another study [28], the same authors considered the effect of magnetohydrodynamic which acts favorably on entropy generation. Numerical simulations were made by Fersadou et al. [29] to study the impact of an external magnetic field on mixed convection and entropy generation in a nanofluid filled vertical porous channel.

Flow reversal phenomenon induced by both assisted and opposed mixed convection in vertical channels has been extensively studied due to its deep effect on flow and heat transfer characteristics. Jeng et al. [30] investigated numerically the mixed convection heat transfer inside a vertical channel with asymmetric wall temperatures. They found that the fluid flow and heat transfer characteristics are independent of the Reynolds number for both the situations with or without flow reversal. The effect of the rheological behavior of a power-law fluid on the condition of flow reversal occurrence for fully-developed mixed convection was considered analytically by Barletta [31]. Criteria for flow reversal appearance were established by Cheng et al. [32] by studying the problem of assisted mixed convection in the entrance region of a vertical rectangular duct both numerically and analytically. Flow reversal in a vertical duct whose walls are either isothermal or maintained at uniform heat flux was analyzed by Barletta [33, 34]. The analytical solution developed allowed the author to delimit the domains within the duct where the flow reversal takes place. Nguyen et al. [35] employed the full 3D-transient-model and Boussinesq’s approximation to analyze flow reversal and instability within a vertical tube for both assisted and opposed mixed convection. Using a time-dependent wall heat flux, the authors highlighted the development of the flow reversal in the tube versus time. A numerical investigation was conducted by Desrayaud and Lauriat [36] to study the flow reversal occurrence at the entry region of a symmetrically heated vertical channel. Heat and mass transfer with phase change inside a vertical parallel-plate channel in laminar mixed convection regime were investigated by Oulaid et al. [37]. Charts and correlations were established in order to predict the flow reversal. This phenomenon was also considered by Tehrani and Nazaripoor [38] for the case of combined assisted mixed convection—radiation heat transfer in parallel plates. Their results revealed an increase of both heat transfer rate and fanning friction coefficient with the occurrence of reversed flow. Fu et al. [39] analyzed numerically the flow reversal and heat transfer mechanisms in a three dimensional vertical channel. The effect of aspect ratio of a vertical three dimensional channel on the onset of flow reversal phenomenon for assisted mixed convection was treated numerically by Yang and Wu [40]. Gao et al. [41] analyzed the flow reversal occurrence for assisted mixed convection of supercritical CO2 flowing through a vertical annular channel under asymmetrical heating conditions. Two maps of flow reversal occurrence were constructed using the most relevant control parameters of the study.

On the basis of this literature review, it appears that the topic dealing with the problem of mixed convection and entropy generation of a nanofluid has been widely treated in the past and continues to be extensively held because of the great interest that this subject represents for researchers and industrialists. It is against that background that this work is put forward with the particularity of using sinusoidal heating and including flow reversal phenomenon. To the best knowledge of the authors this problem has not been considered before, so that the reported results are new and original. The main purpose of this paper is to examine the effects of some pertinent parameters on the characteristics of the fluid flow, heat transfer and entropy generation, as well as the conditions for flow reversal occurrence. It is believed that this study will contribute to improve the thermal performance of electronic cooling systems.

2 Mathematical formulation

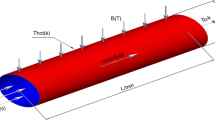

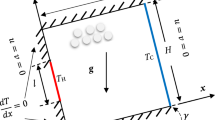

The physical domain considered in this study and shown in Fig. 1, is a vertical channel formed by two parallel plates of length ℓ and separated by a distance H. A copper–water nanofluid, which thermophysical properties are presented in Table 1, enters the channel at uniform velocity, temperature and nanoparticles volume fraction. The right wall is cooled at uniform density qc, while the left one is heated with a non-uniform flux of sinusoidal spatial variation: qh [1 − Asin (2πx/ℓ)]. This kind of periodic heating is encountered in many engineering applications namely the cooling of electronic components.

For a mixed convection regime, the flow is considered laminar, steady-state, incompressible and two-dimensional with the use of the Boussinesq approximation for density variation in the buoyancy force. The viscous dissipation and internal heat generation terms are neglected in the energy equation.

The nanofluid flow and heat transfer in the channel are described using the Buongiorno’s model [42] to account for Brownian and thermophoresis effects.

On the basis of what has been mentioned before, the conservation equations are written as follows:

Continuity

Momentum

Energy

Nanoparticles volume fraction

The expressions of the Brownian diffusion DB and thermophoretic diffusion DT coefficients are given by:

where kB is the Boltzmann’s constant (kB = 1.3807 × 10−23 J K−1) and dp the nanoparticle diameter.

The boundary conditions for the studied problem are:

2.1 Nanofluid properties

The density, thermal expansion coefficient and heat capacitance of the nanofluid are given by:

The Corcione model [43] is used to compute the viscosity and the thermal conductivity of nanofluid:

where df and Tfr are respectively the molecule diameter (df = 3.85 × 10−10 m) and the freezing point (Tfr = 273.15 K) of the base fluid.

Using the non-dimensional variables:

The dimensionless conservation equations can be expressed in the following general form:

Here \({\Phi}\), Γ\(_{\Phi}\) and \({\text{S}}_{\Phi}\) are respectively the dependent variable, the diffusion term and the source term. Their expressions, for the different governing equations, are summarized in Table 2.

The boundary conditions in dimensionless form are:

The dimensionless parameters appearing in the previous equations and boundary conditions are defined as:

The local Nusselt number at the heated wall is evaluated as follows:

The mean Nusselt number is defined as:

2.2 Entropy generation

The local entropy generation is illustrated by the equation below [44]:

The first term is the local entropy generation due to heat transfer irreversibility, the second one is due to friction caused by the flow of nanofluid, while the last term represents the entropy generation associated to Brownian and thermophoresis effects

By dividing Eq. (23) by the rate \(q_{h}^{2} /k_{f} T_{i}^{2}\), we obtain the entropy generation number Ns as suggested by Bejan [45, 46]:

The irreversibility coefficients λ1, λ2 and λ3 are defined by:

The total entropy generation is calculated as follows:

With:

3 Numerical procedure

The Eq. (16), for each dependent variable, with the boundary conditions (17)–(22) is solved numerically using the finite volume method [47] with the SIMPLE algorithm for the pressure–velocity formulation. The power law scheme is adopted for the discretization of the diffusive and the convective terms. The resolution of the obtained algebraic equations is done by the line-by-line technique which is a combination of the Tridiagonal Matrix Algorithm (TDMA) and the Gauss–Seidel iterative method. A non-uniform mesh is considered in the transverse direction with the finer grids located near the channel walls. After several sensitivity tests, it appears that the numerical solution becomes weakly affected by the increase of the nodes number for the grids system of 250 × 50 (in the X and Y directions respectively), where the variation in Nusselt number and total entropy generation is less than 1% as it appears in Table 3. A convergence criterion of the iterative process, based on the maximum relative error between two successive iterations for velocity components, temperature and nanoparticles volume fraction, is adopted with an accuracy of 10−6. The developed computation code is validated by comparing the results of the present study firstly with those of the numerical investigation of Desrayaud and Lauriat [36] in the mixed convection regime inside a vertical plate channel, and secondly with those of the experimental work of Osman et al. [48] conducted in a rectangular channel filled with (Al2O3–water) nanofluid. The velocity and temperature profiles illustrated in Figs. 2a and b respectively, as well as the Nusselt number variation presented in Fig. 3 show a good agreement with a maximum deviation not exceeding 2%.

4 Results

The parametric study is made by fixing the length of the channel L = 30, the Prandtl number Pr = 7 and the Reynolds number Re = 100. The main reason of the choice of this small value of Reynolds number lies in the fact that the extent of the reverse flow region increases with Re and this will not allow to vary the control parameters over a wide range as it is currently the case. The influence of the Richardson number (0.1 ≤ Ri ≤ 10), the heat flux ratio (0.1 ≤ Rq ≤ 1), as well as the nanoparticles volume fraction at the channel inlet (0 ≤ ϕi ≤ 0.05) on the velocity profiles, the mean Nusselt number on the hot wall, together with the entropy generation is considered for both non-uniform (A = 0.5) and uniform (A = 0) heating. To compute the other parameters appearing in the dimensionless equations and boundary conditions, the inlet temperature of the nanofluid is fixed to Ti = 293.15 K, whereas the heat flux densities qh and qc are computed from the expressions of the Richardson number and the heat flux ratio respectively.

The first parameter whose effect is studied is the intensity of the buoyancy force given by the Richardson number. In Fig. 4a are presented the stream-wise velocity profiles for various Ri in the case of non-uniform heating. With the increase of the magnitude of the buoyancy force, the symmetrical shape obtained at low Ri, corresponding to forced convection, changes to an asymmetrical profile. This can be explained by the fact that, since this force acts in the same direction as the main flow at the heated wall and in the opposite direction at the level of the cooled plate, this results in an acceleration of the nanofluid motion in the first region and its slowing-down in the second one. From a given Ri, whose value depends on the other control parameters, the axial component of the velocity becomes negative on the cooled wall side; attesting to a reversal of the flow direction in this region.

This change in velocity profiles will have a direct influence on the rate of heat transfer as shown in Fig. 4b. Whether the heating is uniform or non-uniform, the mean Nusselt number increases with the rise of Richardson number, and this augmentation becomes significant from a value of Ri of the order of 5. Indeed, at low values of the latter, the additional acceleration of the nanofluid motion at the heated wall is caused solely by the buoyancy force which acts in the same direction as the main flow. At large values of Ri, there is in addition the appearance of the flow reversal on the cooled wall side, which causes an increase of the nanofluid velocity in the vicinity of the heated wall to maintain the flow rate. The comparison with the uniform heating case, shows that the application of a heat flux density with sinusoidal spatial variation is better. In fact, for A = 0.5, the left wall is heated on the first half-length of the channel at a density lower than the average value qh, corresponding to the case of uniform heating, and conversely for the second half. The temperature of the coolant fluid is then lower on the first half, and the nanofluid starts cooling the remaining wall length with a higher capacity of absorption of the thermal energy released. This results in a better heat exchange with an improvement ranging between 4 and 7%.

Figure 4c depicts the impact of the buoyancy force on the total entropy generation S, as well as those due to heat transfer Sth and fluid friction Sfr. The irreversibility due to Brownian and thermophoresis diffusions Sbt being very small in comparison to the two others (variation between 10−7 and 10−8), it will not be represented then. Initially, the increase of Ri causes an acceleration of the nanaofluid flow and therefore a reduction of Sfr. However, with the appearance of the flow reversal, at Ri near the value of 4, and the augmentation of its extent in the channel with the strengthen of the buoyancy force, large velocity gradients are then induced leading to an increase in the irreversibility due to fluid friction from Ri = 6. At Richardson number equal to 0.1, the total entropy generation is controlled by the fluid friction since Sfr represents 95% of S. Its contribution decreases and it equalizes the thermal irreversibility at Ri ≈ 0.45. From Ri = 5, the amount of entropy generation due to fluid friction does not exceed 1%. At low values of the Richardson number, entropy generation due to heat transfer occurs at an almost constant rate. However, with the onset of the flow reversal, strong temperature gradients are generated and then Sth increases with Ri. In contrast to Sfr, its contribution in the total value S increases with the rise of the buoyancy force intensity and becomes dominant from Ri = 1 where it represents 85% of the total entropy. This figure reveals that, unfortunately, the heating at non-uniform density rises the entropy generations S and Sth by a rate which can reach 8%.

Figure 5 illustrates the influence of the heat flux ratio on the various characteristics. Since Ri is kept fixed for this case, increase Rq is to cool the right wall with a higher heat flux density qc. The velocity profiles (Fig. 5a) show asymmetrical shapes where the nanofluid flow is accelerated on the side of the heated wall and decelerated in the vicinity of the cooled one. This slowdown is accentuated with the increase of Rq, and from a value of the latter close to 0.35, there is appearance of the flow reversal. To maintain the flow rate constant, the nanofluid velocity increases considerably near the left wall. As a consequence, the heat transfer increases with augmenting Rq as it appears in Fig. 5b. This rise is not very appreciable at low cooling densities qc, but becomes rather important from Rq ≈ 0.4 due to the flow reversal. As seen above, a non-uniform heating seems better regardless of the intensity of the cooling flux, with an improvement in comparison to the case of a constant heating flux density between 4 and 5%. Regarding the entropy generation, Fig. 5c shows that the two types of irreversibility are accentuated by increasing the heat flux ratio with dominance of the heat transfer irreversibility mode which represents 99% of the total entropy generation. This behavior is due to the strong velocity and temperature gradients that are generated by the appearance of the flow reversal and its amplification with Rq. A sinusoidal heating is however unfavorable for total and heat transfer entropy generations with an augmentation rate of up to 8%.

Figure 6a, depicting the effect of the nanoparticles volume fraction on the velocity profiles, shows that by increasing ϕi there is on the one hand, a deceleration of the nanofluid motion in the region adjacent to the hot wall and on the other hand, a decrease in the intensity and the extent of the flow reversal occurring near the cold wall. This is due to the fact that the addition of nanoparticles to the base fluid leads to a reduction in the viscosity of the mixture which will cause a decrease in the convective motion.

By using copper nanoparticles, the convective heat transfer of the mixture will be controlled by two parameters which effects are opposite. First, due to the enhancement of thermal conductivity there is an increase in heat exchanges. Secondly, heat transfer is reduced because of the augmentation of the nanofluid viscosity. Figure 6b shows that in the present study, it is the second effect which has prevailed since Num decreases with the increase of ϕi. In fact, by loading the base fluid by more nanoparticles, the nanofluid flow on the hot wall side is less accelerated (see Fig. 6a) and the exchange is then weaker. An improvement, between 4 and 5%, is obtained by applying a non-uniform heating. In contrast to the heat transfer between the hot wall and the nanofluid, Fig. 6c indicates that the increase of the nanoparticles volume fraction is very favorable for the total entropy generation and for those due to fluid friction and heat transfer since it leads to their decrease. This is probably due to the weakening of the intensity of the flow reversal and thus the diminution of the velocity and temperature gradients inside the channel. The comparison between the contributions of the two modes of irreversibility to the total one, shows that the entropy generation due to the fluid friction represents only 1%. Also, it appears from this figure an increase in entropy generations varying between 2 and 14% when the left wall is heated with a non-constant density.

The map giving the conditions for the onset of flow reversal as a function of the control parameters (Ri, Rq and ϕi) is illustrated in Fig. 7. The curves indicate that for a low cooling density, a large buoyancy force is required for the flow to be inverted, and vice versa at high values of Rq. Concerning the effect of ϕi, this phenomenon appears faster by less charging the base fluid with nanoparticles. Based on these results, a correlation, given by Eq. (28), is proposed to find the critical Richardson number from which the flow reversal appears. Figure 7 indicates that the Eq. (28) predicts very satisfactorily the onset of this phenomenon with a maximum deviation of 5%.

5 Conclusion

Mixed Convection heat transfer and entropy generation characteristics of a nanofluid (copper–water) inside a vertical channel subjected to a sinusoidal heating have been studied numerically. The main findings can be summarized as follow:

-

The onset of the flow reversal is strongly related to the governing parameters of the present study. This phenomena affects considerably the flow, the heat transfer as well as the entropy generation, and becomes more pronounced with the increase of Ri and Rq, and the decrease of ϕi.

-

The Richardson number and the heat flux ratio have increasing effect on the heat transfer rate, while the nanoparticles volume fraction acts oppositely.

-

The entropy generation due to heat transfer is the dominant mode with a mean contribution of the fluid friction irreversibility around 1%.

-

The entropy generation increases with the augmentation of Ri and Rq and the reduction of ϕi.

-

The non-uniform heating enhances the thermal performance of the present physical system and leads to an improvement rate of up to 7% for the mean Nusselt number. However, it is not favorable for the entropy generation with an augmentation which can reaches 14%.

-

A correlation, foreseeing the onset of the flow reversal, is proposed with a deviation from the numerical results not exceeding 5%.

Abbreviations

- A:

-

Amplitude of oscillation

- Cp :

-

Specific heat at constant pressure (J kg−1 K−1)

- df :

-

Molecule diameter of the base fluid (m)

- dp :

-

Nanoparticule diameter (m)

- DB :

-

Brownian diffusion coefficient (m2 s−1)

- DT :

-

Thermophoretic diffusion coefficient (m2 s−1 K−1)

- g:

-

Gravitational acceleration (m s−2)

- H:

-

Channel width (m)

- k:

-

Thermal conductivity (W m−1 K−1)

- kB :

-

Boltzmann’s constant (J K−1)

- ℓ:

-

Channel length (m)

- Le:

-

Lewis number

- NB :

-

Brownian motion parameter

- NBT :

-

Ratio of Brownian to thermophoretic diffusivities

- Ns:

-

Entropy generation number

- NT :

-

Thermophoresis parameter

- Nu:

-

Nusselt number

- p:

-

Pressure (Pa)

- Pr:

-

Prandtl number

- q:

-

Heat flux density (W m−2)

- Re:

-

Reynolds number

- Ri:

-

Richardson number

- Rq :

-

Heat flux ratio

- S:

-

Total entropy generation

- \(S^{\prime \prime \prime }\) :

-

Local entropy generation (W m−3 K−1)

- \({\text{S}}_{\Phi}\) :

-

Source term

- T:

-

Temperature (K)

- Tfr :

-

Freezing point of the base fluid (K)

- u:

-

Axial velocity (m s−1)

- v:

-

Transverse velocity (m s−1)

- x:

-

Axial coordinate (m)

- y:

-

Transverse coordinate (m)

- β:

-

Thermal expansion coefficient (K−1)

- θ:

-

Dimensionless temperature

- μ:

-

Viscosity (kg m−1 s−1)

- ρ:

-

Density (kg m−3)

- \(\upsilon\) :

-

Channel volume

- ϕ:

-

Nanoparticles volume fraction

- \({\Phi}\) :

-

Dependent variable

- λ:

-

Irreversibility coefficient

- Γ\(_{\Phi}\) :

-

Diffusion term

- bt:

-

Brownian and thermophoresis diffusion

- c:

-

Cooled

- f:

-

Fluid

- fr:

-

Fluid friction

- h:

-

Heated

- i:

-

Inlet

- m:

-

Mean

- nf:

-

Nanofluid

- p:

-

Nanoparticles

- th:

-

Thermal

- w:

-

Wall

References

Han ZH, Yang B, Kim SH, Zachariah MR (2007) Application of hybrid sphere/carbon nanotube particles in nanofluids. Nanotechnology. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/18/10/105701

Sundar LS, Singh MK, Sousa ACM (2014) Enhanced heat transfer and friction factor of MWCNT-Fe3O4/water hybrid nanofluids. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf 52:73–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2014.01.012

Arshad W, Ali HM (2017a) Graphene nanoplatelets nanofluids thermal and hydrodynamic performance on integral fin heat sink. Int J Heat Mass Transf 107:995–1001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2016.10.127

Arshad W, Ali HM (2017b) Experimental investigation of heat transfer and pressure drop in a straight minichannel heat sink using TiO2 nanofluid. Int J Heat Mass Transf 110:248–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2017.03.032

Khan MS, Abid M, Ali HM, Amber KP, Bashir MA, Javed S (2019) Comparative performance assessment of solar dish assisted s-CO2 Brayton cycle using nanofluids. Appl Therm Eng 148:295–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2018.11.021

Sarkarn J, Ghosh P, Adil A (2015) A review on hybrid nanofluids: recent research, development and applications. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 43:164–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.11.023

Ali HM, Babar H, Shah TR, Sajid MU, Qasim MA, Javed S (2018) Preparation techniques of TiO2 nanofluids and challenges: a review. Appl Sci 8:587. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8040587

Sajid MU, Ali HM (2018) Thermal conductivity of hybrid nanofluids; a critical reviw. Int J Heat Mass Transf 126:211–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.05.021

Sajid MU, Ali HM (2019) Recent advances in application of nanofluids in heat transfer devices: a critical review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 103:556–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.12.057

Xu H, Pop I (2012) Fully-developed mixed convection flow in a vertical channel filled with nanofluids. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf 39:1086–1092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2012.06.003

Fakour M, Vahabzadeh A, Ganji DD (2014) Scrutiny of mixed convection flow of a nanofluid in a vertical channel. Case Stud Therm Eng 4:15–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2014.05.003

Malvandi A, Ganji DD (2014) Mixed convective heat transfer of water/alumina nanofluid inside a vertical microchannel. Powder Technol 263:37–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2014.04.084

Malvandi A, Ganji DD (2015) Effects of nanoparticle migration on hydromagnetic mixed convection of alumina/water nanofluid in vertical channels with asymmetric heating. Phys E 66:181–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physe.2014.10.023

Hedayati F, Domairry G (2015) Effects of nanoparticle migration and asymmetric heating on mixed convection of TiO2–H2O nanofluid inside a vertical microchannel. Powder Technol 272:250–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2014.12.003

Malvandi A, Moshizi SA, Ganji DD (2016) Effects of temperature-dependent thermophysical properties on nanoparticle migration at mixed convection of nanofluids in vertical microchannels. Powder Technol 303:7–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2016.08.063

Malvandi A, Moshizi SA, Ganji DD (2016) Two-component heterogeneous mixed convection of alumina/water nanofluid in microchannels with heat source/sink. Adv Powder Technol 27:245–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2015.12.009

Das S, Jana RN, Makinde OD (2015) Mixed convective magnetohydrodynamic flow in a vertical channel filled with nanofluids. J Eng Sci Technol 18:244–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jestch.2014.12.009

Li B, Zhang W, Zhu L, Zheng L (2017) On mixed convection of two immiscible layers with a layer of non-Newtonian nanofluid in a vertical channel. Powder Technol 310:351–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2017.01.054

Moshizi SA, Zamani M, Hosseini SJ, Malvandi A (2017) Mixed convection of magnetohydrodynamic nanofluids inside microtubes at constant wall temperature. J Magn Magn Mater 430:36–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2017.01.053

Hosseini SJ, Malvandi A, Moshizi SA, Zamani M (2017) Fully developed mixed convection of nanofluids in microtubes at constant wall temperature: anomalous heat transfer rate and thermal performance. Adv Powder Technol 28:721–731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2016.11.019

Mehrez Z, Bouterra M, El Cafsi A, Belghith A (2013) Heat transfer and entropy generation analysis of nanofluids flow in an open cavity. Comput Fluids 88:363–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2013.09.026

Mehrez Z, El Cafsi A, Belghith A, Le Quere P (2015) The entropy generation analysis in the mixed convective assisting flow of Cu–water nanofluid in an inclined open cavity. Adv Powder Technol 26:1442–1451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2015.07.020

Bouchoucha AEM, Bessaih R, Oztop HF, Al-Salem K, Bayrak F (2017) Natural convection and entropy generation in a nanofluid filled cavity with thick bottom wall: effects of non-isothermal heating. Int J Mech Sci 126:96–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2017.03.025

Bezi S, Souayah B, Ben-Cheikh N, Ben-Beya B (2018) Numerical simulation of entropy generation due to unsteady natural convection in a semi-annular enclosure filled with nanofluide. Int J Heat Mass Transf 124:841–859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.03.109

Mehryan SAM, Izadi M, Chamkha AJ, Sheremet MA (2018) Natural convection and entropy generation of a ferrofluid in a square enclosure under the effect of a horizontal periodic magnetic field. J Mol Liq 263:510–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2018.04.119

Hajialigol N, Fattahi A, Ahmadi MH, Qomi ME (2015) MHD mixed convection and entropy generation of a nanofluid in a 3-D microchannel using Al2O3–water nanofluide. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 46:30–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2014.09.002

Chen CK, Chen BS, Liu CC (2014) Heat transfer and entropy generation in fully-developed mixed convection nanofluid flow in vertical channel. Int J Heat Mass Transf 79:750–758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2014.08.078

Chen CK, Chen BS, Liu CC (2015) Entropy generation in mixed convection magnetohydrodynamic nanofluid flow in vertical channel. Int J Heat Mass Transf 91:1026–1033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2015.08.042

Fersadou I, Kahalerras H, El Ganaoui M (2015) MHD mixed convection and entropy generation of a nanofluid in a vertical porous channel. Comput Fluids 121:164–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2015.08.014

Jeng YN, Chen JL, Aung W (1992) On the Reynolds-number independence of mixed convection in a vertical channel subjected to asymmetric wall temperatures with and without flow reversal. Int J Heat Fluid Flow 13:329–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/0142-727X(92)90003-R

Barletta A (1999) On fully-developed mixed convection and flow reversal of a power-law fluid in a vertical channel. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf 26:1127–1137. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1933(99)00103-7

Cheng CH, Weng CJ, Aung W (2000) Buoyancy-assisted flow reversal and convective heat transfer in entrance region of a vertical rectangular duct. Int J Heat Fluid Flow 21:403–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0142-727X(00)00005-9

Barletta A (2001) Analysis of flow reversal for laminar mixed convection in a vertical rectangular duct with one or more isothermal walls. Int J Heat Mass Transf 44:3481–3497. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0017-9310(01)00016-3

Barletta A (2002) Fully developed mixed convection and flow reversal in a vertical rectangular duct with uniform wall heat flux. Int J Heat Mass Transf 45:641–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0017-9310(01)00160-0

Nguyen CT, Maiga SEB, Landry M, Glanis N, Roy G (2004) Numerical investigation of flow reversal and instability in mixed laminar vertical tube flow. Int J Therm Sci 43:797–808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2004.02.020

Desrayaud G, Lauriat G (2009) Flow reversal of laminar mixed convection in the entry region of symmetrically heated, vertical plate channels. Int J Therm Sci 48:2036–2045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2009.03.002

Oulaid O, Benhamou B, Glanis N (2010) Flow reversal in combined laminar mixed convection heat and mass transfer with phase change in a vertical channel. Int J Heat Fluid Flow 31:711–721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatfluidflow.2010.04.007

Tehrani FB, Nazaripoor H (2011) Buoyancy-assisted flow reversal and combined mixed convection-radiation heat transfer in symmetrically heated vertical parallel plates: influence of two radiative parameters. Sci Iran 8:974–985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scient.2011.07.008

Fu WS, Lai YC, Huang Y, Liu KL (2013) An investigation of flow reversal of mixed convection in a three dimensional rectangular channel with finite length. Int J Heat Mass Transf 64:636–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2013.04.025

Yang G, Wu JY (2014) Effect of aspect ratio and assisted buoyancy on flow reversal for mixed convection with imposed flow rate in a vertical three dimensional rectangular duct. Int J Heat Mass Transf 77:335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2014.05.027

Gao W, Abdi-khanghah M, Ghoroqi M, Daryasafar A, Lavasani M (2018) Flow reversal of laminar mixed convection for supercritical CO2 flowing vertically upward in the entry region of asymmetrically heated annular channel. J. Supercrit. Fluids 131:87–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.supflu.2017.09.007

Buongiorno J (2006) Convective transports in nanofluids. Trans ASME J Heat Transf 128:240–250. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2150834

Corcione M (2011) Empirical correlating equations for predicting the effective thermal conductivity and dynamic viscosity of nanofluids. Energy Convers Manag 52:789–793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2010.06.072

Mkwizu MH, Makinde OD (2015) Entropy generation in a variable viscosity channel flow of nanofluids with convection cooling. Comp Rend Méc 343:38–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crme.2014.09.002

Bejan A (1982) Second-law analysis in heat transfer and thermal design. Adv Heat Transf 52:1–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2717(08)70172-2

Bejan A (1996) Entropy generation minimization. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Patankar SV (1980) Numerical heat transfer and fluid flow. Mc Graw-Hill, New York

Osman S, Sharifpur M, Meyer JP (2019) Experimental investigation of convective heat transfer in the transition flow regime of aluminium oxide-water nanofluids in a rectangular channel. Int J Heat Mass Transf 133:895–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.12.169

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kahalerras, H., Fersadou, B. & Nessab, W. Mixed convection heat transfer and entropy generation analysis of copper–water nanofluid in a vertical channel with non-uniform heating. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 76 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1869-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1869-2