Abstract

Previous research has shown that group processes are particularly pertinent to children’s bullying, and who they socially exclude and include. This paper looks at how children’s responses to social exclusion change according to their friends’ group-based emotions. Children aged 8–11 years (N = 77) read stories about a friendship group to which they were said to belong and an instance of mild social exclusion. In the stories, the participants’ friends’ emotional reaction to the exclusion (pleased versus angry) was manipulated. Measures of assertive bystanding intentions and responses towards the friendship group and the social exclusion were taken. Children showed more assertive bystanding intentions when their friendship group was depicted as angry and they reported more anger when reacting to social exclusion. A mediation effect was found, with a perception of the friendship group’s emotion as anger being related to increased assertive bystanding, through an increase in the participant’s own anger towards their group’s act of social exclusion. This study is among the first to show that from 8 years of age, the social appraisal of group emotions can account for children’s reactions to social exclusion in a friendship group. Directions for future research in social appraisal of group-based emotion in social exclusion situations are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Bullying may be conceived of as aggression comprised of three identifying features (1) behavior intended to do harm, (2) behavior that is repeated over time, and (3) behavior that takes place in a social context in which there is an imbalance of power. It may include indirect aggression, or relational aggression, covering the withdrawal of friendship, spreading of gossip, and social exclusion (Smith 2004). Social exclusion is a particularly pernicious form of bullying that may be defined as the “experience of being kept apart from others physically or emotionally” (Riva and Eck 2016, p. ix). Social exclusion (that is, exclusion from groups to which a child belongs by members of that group) may be particularly pernicious because, unlike for other forms of bullying, children who are rejected in this way are left without the support of the peer group, to help them deal with this rejection. This form of rejection is of concern in childhood because it has a deleterious impact on a number of psychological processes (e.g., Williams 2009). In the short-term, social exclusion demonstrably adversely affects fulfillment of the emotional need to belong (Abrams et al. 2011), negatively impacts the way children think about themselves (Hawes et al. 2012), and causes withdrawal from learning (Buhs et al. 2006). In the longer-term, research has shown that experiencing (especially sustained) social exclusion is linked with increased risk for depression and anxiety (e.g., Epkins and Heckler 2011; Hamilton et al. 2015). There is then a good case in reducing incidents of social exclusion from peer groups at school.

One route by which this may happen is through harnessing the power of bystanders. That is, on the playground, it is recognized that bystanders are often present during incidents of social exclusion (e.g., Barhight et al. 2013; Pozzoli et al. 2012). When children intervene as assertive bystanders, social exclusion is more likely to end (e.g., Hawkins, Pepler, and Craig 2001). The key then is to determine what leads to active over passive bystanding in the face of social exclusion. In this regard, relatively little attention has been paid to bystanders’ emotional responses to witnessing bullying. Accordingly, the central aim of the study reported here was to examine children’s emotional responses to witnessing social exclusion of someone said to be in their friendship group. Specifically, we look at how a child’s perception of ingroup members’ [other bystanders] emotional responses to the social exclusion, inform their own emotional response, and in turn, their assertive bystanding intentions.

Social Exclusion

Extensive previous research has looked at emotion in the context of interpersonal and intergroup exclusion. For example, at the interpersonal level, research on social exclusion has focused on individual factors such as targets’ maladaptive attributional styles (Vanhalst et al. 2015), targets’ social problem solving skills (Rigby 2005), or targets having an aggressive or shy temperament (Bierman et al. 2015). We argue, in line with Horton (2011) and Schott and In Søndergaard (2014) that this research provides one part of the puzzle of social exclusion. The other part of this puzzle concerns the target’s (and the perpetrator’s) peer group and group processes of inclusion and exclusion.

At the intergroup level, research on social exclusion has examined cognitive and affective responses attributed to perpetrators and targets by children who are often cast as a third party group member. In this vein, it has been shown that observing the exclusion of another person elicits negative emotion similar to the distress caused by firsthand exclusion (Masten et al. 2011). Research also shows increased activation in brain areas sensitive to social cues while participants watch social exclusion, and in turn, this has been associated with increased concern for the target among adolescents (Masten et al. 2010). Research investigating intergroup social exclusion has also elucidated the role of children’s cognition and emotion in their actual social exclusion behavior (e.g., Hitti et al. 2014). Such research has highlighted a complex interplay between moral and social considerations. Specifically, perspective taking ability, social-contextual factors, anticipated emotion evaluations, moral norms concerning harm prevention, and group norms surrounding loyalty all influence children’s intergroup exclusion decisions. In this vein, Malti et al. (2015) investigated judgments and moral emotions in contexts of intergroup social exclusion. Children were asked to ascribe emotions to an excluding group, an excluded target, and to onlooking versus including bystanders. Children expected more pride to be experienced by the excluding group when there was an audience of onlooking bystanders than when there were no bystanders present. Furthermore, adolescents expected including bystanders to experience more empathy than onlooking bystanders and anticipated more guilt among onlooking bystanders than including bystanders.

Group-Based Emotion

The question of whether children experience emotion on behalf of a group to which they belong, and whether emotion perceived in other group members will, in turn, affect their own emotional responding remains open. There is evidence that group-based emotions may be elicited by intergroup social exclusion incidents (Jones et al. 2011; Jones et al. 2012a; Jones et al. 2009). Group-based emotions originally hypothesized by E.R. Smith (1993) are those emotions which hold the subject and object of emotion at the group rather than the individual level (Parkinson et al. 2005). In other words, these are emotions that an individual group member experiences in relation to a group-relevant event (for example, pride in a sporting team win that the individual supports, despite not having played for the team). A burgeoning literature now demonstrates that group-based emotions are relevant to adults’ interpretation of intergroup events (see Iyer and Leach 2008, for a review). In particular, this research suggests that group-based emotions, such as anger, mediate a link between perceptions of a group event and a tendency to act in response to it. For example, Harth et al. (2013) showed that group-based guilt and anger mediated a link between perception of group responsibility for damaging environmental behavior and a willingness to mitigate for that damage.

Building on adult research, Jones et al. (2009, 2011, 2012b), in a series of studies, assigned 9- to 11-year-olds to the same minimal group as story characters who were said to be engaging in social exclusion. Children read a story in which a protagonist, in the presence of their friendship group, acted unkindly towards a child from a different group. In Jones et al. (2011), group-based pride and anger were tested. Group-based pride may be defined as a positive, in-group-focused emotion relating to group-level responsibility for an action (e.g., Tracy and Robins 2007). It was included within this study in recognition of the finding that some friendship groups hold pro-bullying norms that condone bullying (e.g., Sentse, Scholte, Salmivalli, and Voeten 2007). Group-based anger, on the other hand, is construed as stemming from appraisal of a group behavior as unfair (e.g., Scherer et al. 2001). It is associated with movement to act against those who have caused the unfairness (e.g., Harth et al. 2013). In the aforementioned studies, it was found that children’s randomly assigned group membership predicted the level of group-based emotion they cited, such that those in the group instigating the social exclusion reported more pride, and those in the same group as the child being excluded reported more anger, at the social exclusion. It was group-based anger, and not pride, that was associated with assertive bystanding in these studies. For this reason, the group-based emotions of pride and anger are measured in the study reported below.

What is apparently missing is an account of children’s emotions when exclusion is proposed or happens at the intragroup level. Intragroup processes pertain to judgments that people, including children, make about members in the groups to which they belong. It has been shown that older children (aged 10–11 years) are sensitive to intragroup differences between ingroup members and make judgements concerning punishment and exclusion based on a group member’s behavior vis-à-vis group values (Abrams et al. 2017, 2003). To our knowledge, no research has examined the impact of emotions experienced from being a group member on intragroup social exclusion. Research concerning intragroup exclusion shows that older children understand that it is more probable that they will be excluded by the group when they deviate from the norms of that group in some way (e.g., Zdaniuk and Levine 2001; Killen and Rutland 2011). Research also indicates that children’s condoning of social exclusion from a group is fluid, as they seek to protect their own belongingness (Schott and In Søndergaard 2014; Horton 2011) and that among children, the positive ingroup image can be boosted through negative judgments cast on ingroup members (e.g., Hitti et al. 2014). Indeed, research shows that negative judgments of others are intensified when they are ingroup rather than outgroup members perhaps precisely because group members are motivated to protect the group’s values.

Other research on intragroup exclusion, in line with the work on intergroup exclusion, has shown that children and adolescents will sometimes condone exclusion of an ingroup member who deviates from the group for positive moral reasons but does not condone exclusion for negative antisocial reasons (Hitti et al. 2014). Similarly, it has been shown that children judge social exclusion based on group membership as more unfair than exclusion based on personality traits (Park and Killen 2010). In other words, children take account of both social and moral concerns in their judgments of intragroup exclusion scenarios. Elsewhere it has been shown that, given the opportunity, children will compensate those who their group earlier excluded from a cyberball game (Vrijhof et al. 2016; Will et al. 2013). There is then good evidence of children’s acute sensitivity to ingroup members’ behavior that takes account of social and cognitive variables, evidence that children respond emotionally at the interpersonal and intergroup level and evidence that intergroup exclusion has deleterious outcomes. Taken together, this means it is timely to consider the emotions attached to intragroup exclusion scenarios. Such evidence might then serve as an avenue to mending the group relations that led up to the opportunity for social exclusion from a friendship group.

Social Appraisal of Emotion

The above research shows that group-based emotion is pertinent to social exclusion. However, it has taken a first-person perspective on social exclusion: children were told that they shared a group membership with children who had engaged in, or been the targets of social exclusion, and were asked about the group-based emotions they imagined they would respond with in this situation. Children were not asked about how other members of their ingroup might respond at the emotional or behavioral level (and how this might influence their own response). Drawing together research by Malti et al. (2015) showing that children can judge and attribute moral emotion to others, and Jones et al. (2009, 2011) showing that group factors are relevant to emotional experience, we look here at whether children integrate concerns, about their later inclusion in a friendship group, with their ability to perceive emotion in others [or in fellow group members]. In other words, we look for the first time at whether children engage in social appraisal to judge intragroup social exclusion scenarios.

Research on social appraisal theory has shown that adults’ own emotional reactions to a group-relevant event may differ according to what they imagine others are feeling (Manstead and Fischer 2001). Thus, while a group-relevant event can elicit group-based emotion, this theory additionally posits that group-based emotion expressed by ingroup members can have a reciprocal effect upon the situation in shaping one’s own expressed emotion (Parkinson 1996). Others’ emotional expression therefore communicates how one could respond to a group-relevant event. For example, expressing anger communicates to group members that this is an event to which they might object (Parkinson 1996). Moreover, such expressions of anger can prompt collective support in resisting the incident causing disapproval (Thomas et al. 2009). In this vein, Livingstone et al. (2016) measured their participants’ emotional responses to a group-relevant event. They then manipulated the emotional responses of other ingroup members. They found that an alignment of emotional reactions predicted participants’ willingness to take part in collective action. To apply this theory to a social exclusion context, one might manipulate the group-based emotions children imagine other friendship group members are experiencing, and examine whether they are driven to align their emotional reactions with those of other children and are thus more likely to contest that social exclusion. To this end, in the present research, ingroup members’ emotional responses to social exclusion were manipulated to determine the effect that this would have upon participants’ own group-based emotion and assertive bystanding intentions.

The Development of Social Appraisal

Having established that social appraisal takes place among adults, it becomes important to determine the age at which it might become manifest in children. Social appraisal requires the capacity to (a) reason about emotion in others and (b) to do so as a group member, with the likely attendant motivation to conform to the group. For the purposes of the present study, the children will also need to be sensitive to the effects of peer group inclusion and exclusion. In this regard, there is good evidence that children, from a very young age, have the ability to reason about emotion. However, previous research suggests that only from 8 years of age do children understand that others could react differently emotionally to different situations (Gnepp et al. 1987). Research also shows that only from approximately 7 years of age do children feel the emotion of embarrassment on behalf of their social group, and therefore, apologize for their social group (Bennett et al. 1998). This suggests it is unlikely that children younger than 7 years of age would experience emotion with reference to group membership (Sani and Bennett 2004).

Other research on the development of children’s emotions surrounding social exclusion (e.g., Killen and Malti 2015) suggests that only children above 7 to 8 years of age understand the long-term effects of the social exclusion (e.g., sadness) and tend to attribute negative emotions to the self in the social excluder role. This finding is consistent with other developmental research (Abrams and Rutland 2011; Nesdale 2007) showing children above approximately 8 years of age have a more nuanced understanding of group processes (i.e., group nous) and are, therefore, more likely to be apprehensive of being rejected from the group and are less likely to intervene as bystanders (Palmer et al. 2015). Given the research showing the development the group nous and emotional understanding from approximately 8 years of age, in this study we chose to study 8–11-year-olds since children of this age are likely to have the requisite social and emotional capacity for social appraisal.

Current Study

In line with the above arguments, we sought to examine the effects of friends’ emotional reactions to social exclusion on participants’ group-based emotion and, in turn, assertive bystanding intentions in response to an instance of social exclusion enacted by a member of their friendship group. Since it is known that in scenario-based research on bullying, children’s responses differ according to the gender of the protagonists (see Fox et al. 2014) children aged 8–11 years read a description of a gender-matched friendship group to which they were said to belong to at school (since gender was not a central concern of this study). We predicted, in line with social appraisal theory, that friendship group members’ angry reaction would enhance participants’ own group-based anger.

Method

Participants

Following ethical approval and the consent of head teachers, parental consent forms requesting opt-in consent were sent to 159 children in school year 4, 5, or 6 (aged 8–11 years) in three schools in England, yielding a sample of 77 children (parental response rate of 48%) 24 male and 53 female) whose mean age was 10.14 years (SD = 0.89 years).

Design

The study had a between-subjects experimental design, where the manipulated factor was the group-based emotion displayed by the participant’s friendship group [pleased versus angry]. Group-based emotions of pride and anger, and intention to engage in assertive bystanding were treated as dependent variables.

Materials and Procedure

The study was conducted in school classrooms, one class group at a time, each consisting of between 20 and 29 pupils. Children worked quietly on all experimental tasks. Data collection was administered by the first author. A teacher was always present. The session began with an explanation that the researchers were interested in finding out about children’s friendship groups. The activities involved in the study were then described, and children were reminded that their participation was voluntary. Children who did not wish to take part in the study worked on activities on a friendship theme in a different room.

Practice Items

Each child was given a copy of the relevant gender-matched questionnaire. The questionnaires concerning characters’ angry or pleased response to the social exclusion were randomly distributed among participants. Instructions were read to the children, who proceeded to work through the practice questions. Then followed description of a friendship group, taken from Jones et al. (2011) (e.g., “Claire/Pete and her/his friends are a group of children at Lingley Primary School. Most of Claire/Pete’s friends are sporty, and they enjoy listening to music together”). Children worked through the rest of the questionnaire quietly. Participants were given approximately 30 min to complete this task. Some children were assisted in scenario and questionnaire reading, so as not to exclude those with reading difficulties.

Scenarios

Children read one of four illustrated scenarios. They were given information about the friendship group, about one named member of the group, and about an instance of social exclusion. Children received a scenario about a walk home from school made by Claire/Pete’s group. During this walk, Claire/Pete delivers an unkind verbal message (“Guess who’s not invited to our party tonight? That’s right—you!”) to Amy/Tom [the target, in the same friendship group]. After this is the manipulation of friendship group emotion, “Claire/Pete’s friends laughed. [But] you notice that some of Claire/Pete’s friends look quite [angry/pleased] with her/him.” The scenario ended by making it clear that the target was upset. Scenario protagonists were said to attend a school similar to the participants’. Copies of the scenarios and materials used in both studies are available from the first author on request.

Questionnaires

There were two versions of the questionnaire, one keyed for female participants, and one for male participants. Most items took the form of statements. Unless otherwise stated, children were asked to indicate (by placing a tick) their responses on 5-point scales, ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly). The first set of items related to the behavior described in the scenario, starting with a manipulation check item relating to the named story characters. “Who received the message?” There was also a manipulation check concerning the reaction of the friendship group: “Claire/Pete’s friends looked [pleased/angry] with her/him.”

Following this were items assessing responses to the behavior, judgments of the intentions of the protagonists, and whether the behavior could be called social exclusion. The next set of items concerned participants’ group-based emotions (pride and anger), as used by Jones et al. (2011, 2012a). Three items assessed pride: “I [feel proud about/admire/respect] the way [Perpetrator’s] group behaved on the way home,” α = .69). Three items assessed anger “I feel [angry/annoyed/irritated] about the message sent to [Target],” α = .82). A further set of items concerned participants’ action tendencies, again as used by Jones et al. (2011). Participants reported what they believed they would have done had they been present when the incident took place. These items included the scale of assertive bystanding with five items, “I would help [Target],” “I would try to make friends with Target,” “I would go and tell an adult what had happened,” “I would tell Perpetrator and her/his friends that leaving Target out was wrong,” and “I would let Target play with me and my friends” (α = .70). The final section of the questionnaire asked participants to state their age and year group.

At the conclusion of the session, which lasted approximately 45 min, participants were thanked and debriefed about the research. Any questions that pupils had were addressed by the researchers and pupils were reminded of positive strategies for dealing with any experiences of social exclusion.

Results

Data Screening

Prior to analysis, the data were screened for outliers and for violations of parametric data assumptions. One univariate outlier was pinpointed; to ensure that it was not having a disparate influence on the results, it was removed for each analysis.

Comprehension Check

Analyses indicated that all children passed the check asking “Who sent the message to [Target]?” correctly identifying the sender of the message.

Friendship Group Emotion Manipulation Check

A one-sample t test on the manipulation check revealed that most children scored significantly higher than the scale midpoint, t (76) = 7.66, p < .001, when answering the question, “Claire/Pete’s friends looked [pleased/angry] with her/him” M = 3.79, SD = 0.91.

Effects on Participant Group-Based Anger

A one-way 2 (Friendship Group Emotion: Pleased versus Angry) ANCOVA was conducted on participants’ group-based Anger, with age as a covariate. This revealed a main effect of friendship group emotion, F (1, 76) = 4.47, p = .017, ƞp2 = .090, arising because those in the angry condition were more angry than those in the pleased condition, Ms = 4.37 and 3.85 respectively. Age was not a significant covariate.

Assertive Bystanding

A two-way 2 (Friendship Group Emotion: Pleased versus Angry) × participants’ group-based anger (centered, continuous) × age ANCOVA was conducted on assertive bystanding intentions. This revealed a two-way interaction between friendship group emotion and participants’ group-based anger (centered), F (1, 76) = 4.45, p = .038, ƞp2 = .058, and that age was a significant covariate, F (1, 76) = 5.77, p = .019, ƞp2 = .074.

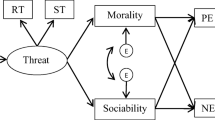

Simple effects analysis revealed that this interaction arose because in the friendship group emotion angry condition, there was a significant difference in assertive bystanding intentions between high (+ 1 SD above the mean) and low (− 1SD below the mean) participant group-based anger, F (1, 76) = 7.33, p = .008, ƞp2 = .092, Ms = 5.74, and 4.80 respectively. The commensurate difference in participant group-based anger was not seen in the friendship group emotion pleased condition F (1, 76) = 3.08, p = .084, ƞp2 = .041, Ms = 5.73 and 5.39 respectively. In other words, where participants’ own anger was lower in the friendship group emotion angry condition (and social appraisal had not occurred), this led to less assertive bystanding than when high participant group-based anger had been elicited by presenting the group emotion as one of being angry. This interaction is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Regression analysis with age as the predictor and assertive bystanding as the outcome variable, revealed a negative association, F (1, 76) = 3.71, B = −0.15, t (76) = −1.97, p = .029. As age increases, the tendency for assertive bystanding decreases, regardless of friendship group emotion condition or participants’ group-based anger (Table 1).

Mediation

Mediation analysis was conducted to explore whether participants’ anger mediated the effect of the manipulated friendship group emotion [angry/pleased] on assertive bystanding. In total, three variables were included in the final model. The outcome variable was assertive bystanding and the mediator was participants’ anger, both of which were measured on a Likert-type scale. The independent variable was friendship group emotion [anger = 1, pleased = 0]. Participants’ age was initially added as a covariate, but since it was not significant, the simpler model, without age as a factor, is reported below. Swapping participant group-based anger for friendship group emotion as the mediator did not produce a significant model.

Analysis by PROCESS Model 4 (Hayes 2013) using 5000 bootstrap samples was used to test for an indirect effect of friendship group emotion on assertive bystanding via participants’ own group-based anger. Results indicated that friendship group emotion was a significant predictor of participant group-based anger, b = .522, SE = .215, p = .018, and that participant anger was a significant predictor of assertive bystanding, b = .257, SE = .095 p = .009. These results support the mediational hypothesis. Friendship group emotion was no longer a significant predictor of assertive bystanding after controlling for the mediator, participant anger, b = − .065, SE = .132, ns, consistent with full mediation. Approximately 16% of the variance in assertive bystanding was accounted for by the predictors (R2 = .156). These results indicated the indirect coefficient was significant, b = .134, SE = .063, LLCI = .038, ULCI = .293. That it, in line with our prediction, was found that making children think their friendship group’s emotion to the social exclusion was anger increased assertive bystanding via increasing the participants’ own anger towards their group’s act of social exclusion (Fig. 2).

Discussion

This study examined the conditions under which children intend to respond supportively as bystanders to an instance of social exclusion completed by a peer from their friendship group. We found a decrease in bystander intentions for helping an excluded peer, and for the first time, showed the relevance of social appraisal mechanisms to the elicitation of group-based anger and assertive bystander intentions. When children thought their friendship group was angry about the social exclusion within the group and they themselves were higher in anger when reacting to the social exclusion, there was more evidence of assertive bystanding intentions. It was also shown that participants’ own group-based anger mediated the association between friendship group members reported group-based emotion and assertive bystanding intentions. The perception that the group’s emotion was one of anger was related to increased assertive bystanding through an increase in the participant’s own anger towards their group’s act of bullying in the form of social exclusion.

The present study makes an original contribution by identifying, for the first time, the existence of social appraisal of group-based emotion in children from 8 years of age and its subsequent effect upon reported emotion and assertive bystander intentions in a friendship group context. Additionally, we build on existing research that shows that group-based anger is linked to assertive bystanding (Jones et al. 2009, 2011, 2012b) and on the relevance of friendship group processes, for children’s responses to group-relevant events (e.g., Nesdale et al. 2005; Nesdale, Milliner, Duffy, and Griffiths 2009). We extend it further by looking at how other group members’ emotion responses affect children’s own response, supporting the work of Schott and In Søndergaard (2014) and Horton (2011) indicating that children’s responses are malleable and fluid, reflecting the group situation with which group members are faced, and taking account of the reaction of other group members.

Practical Implications

Taken together, these results advance our understanding of when children help peers who experience social exclusion perpetrated by someone to whom they are affiliated. Importantly, our findings reiterate the relevance to teachers and parents of examining the group processes underpinning bystander responses (Palmer et al. 2015; Jones et al. 2011). Specifically, it will be important for adults to create educational environments that foster acceptance and inclusion of all classmates. It will also be important to encourage students to think critically and mindfully, vis-à-vis the responses of their peer group, around incidents of social exclusion from the friendship group. In this way, teachers may be able to reduce the likelihood of peer bullying and enhance assertive bystander responses.

Limitations and Future Directions

A further consideration is the role of development (of children’s age) in social appraisal. We chose to study 8–11-year-olds to test for the existence of social appraisal mechanisms because existing work on children’s emotional understanding (Harris et al. 1981) and group nous (Abrams and Rutland 2008) suggested that children of this age had the requisite social and emotional capacity for social appraisal. Given the tendency for less assertive bystanding with increased age here, and in other research on bystander intentions (e.g., Palmer et al. 2015) charting the ways in which children and adolescents deal emotionally with intragroup social exclusion might further explain this reticence. Alternatively, it may be the case that children’s increasing understanding of group dynamics with age leaves them more likely to adhere to group norms that condone bullying, and less likely to defend its targets. The underpinning motivation for less assertive bystanding with age might rest with the cognitive or emotional factors that are pertinent to group processes and this should be explored in future research.

The focus here was on group-based anger since this was known to be associated with assertive bystanding (see Jones et al. 2009, 2011). Anger is also known to mediate the relationship between empathic concern for a target and assertive bystanding (Pozzoli et al. 2017). In this regard, Trach and Hymel (2019) also report that adolescents are over five times more likely to move to stop the bullying or comfort the target if they felt angry about the situation. However, we also anticipated that increased expressions of pride in the bullying among group members would be associated with less assertive bystanding, in line with past research (Jones et al. 2009, 2011, 2012b), and this effect was not seen here. This might be down to a difference in the measure of assertive bystanding across these studies: support for the bullying per se and a desire to be friends with the bullying children was not measured here, as it was in Jones et al. (2009, 2011, 2012a). Nonetheless, the group-based affect that leads to less assertive bystanding and to greater support for bullying children would be worth untangling in future studies. It might also consider a wider range of group-based emotions, including regret, across age groups since adult research highlights that social appraisal has a role here (see Van Der Schalk et al. 2015). Further research might also use a neutral emotion baseline condition rather than manipulating anger versus pride.

The present findings also indicate fruitful areas for future research, given the established link between group membership and normative group behavior. In this regard, it has been demonstrated in both child (Jones et al. 2012b) and adult (e.g., Jetten et al. 1997) that research on positive group-based identification is enhanced to the extent that an action is consistent with that of group norms, while counter normative behavior is considered to be a group threat (Doosje et al. 2002). We propose an extension of this: namely, that children might also respond emotionally according to how normatively acceptable they see a peer group member’s behavior to be and that this might be separate from their personal emotional reaction to the behavior, or their own judgments surrounding acceptability. In other words, in line with social appraisal accounts of group behavior (see Parkinson and Manstead 2015; Evers et al. 2005; Manstead and Fischer 2001), a group of children might each be feeling group-based anger following a group-relevant event, but each suppressing its expression and consequent impulses to act, if the group norm is supportive of social exclusion. The interaction between personal emotional reactions, perceptions of how others are feeling, and different normative contexts is thus an avenue for future research that might help to explain why children’s emotional responding changes with group membership.

Within the present study, predictors of bystander intentions were the focus. We acknowledge that intentions are not the same as actual behaviors. However, research conducted with adults has shown that the ways in which people react to emotion-inducing vignettes parallel the ways in which they respond to “real-life” events (Robinson and Clore 2001). Furthermore, in a meta-analysis, van Zomeren et al. (2008) showed that there is similarity between intentions and behavior in the case of collective action research. To strengthen the current findings, nonetheless, it would be important to replicate the study to look at actual experiences of social exclusion (Salmivalli 2010).

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study identified that a key part of children’s intentions to respond assertively to social exclusion may rely upon social appraisal—an appreciation of how their friends are responding emotionally. The findings of this study highlight the importance of considering social and emotional appraisal processes when seeking to promote assertive bystanding, which may, in turn, reduce incidents of aggression in schools. Future research may usefully consider the exact intragroup and normative contexts that facilitate social appraisal, in order to encourage children to act positively upon the anger they experience when witnessing social exclusion from their friendship group.

References

Abrams, D., & Rutland, A. (2008). The development of subjective group dynamics. In S. R. Levy & M. Killen (Eds.), Intergroup attitudes and relations in childhood through adulthood (pp. 47–65). New York: Oxford University Press.

Abrams, D., & Rutland, A. (2011). Children’s understanding of deviance and group dynamics: the development of subjective group dynamics. In J. Jetten & M. Hornsey (Eds.), Rebels in groups: dissent, deviance, difference and defiance (pp. 135–157). Oxford: Blackwell.

Abrams, D., Rutland, A., Cameron, L., & Marques, J. (2003). The development of subjective group dynamics: when in-group bias gets specific. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 21, 155–176. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151003765264020.

Abrams, D., Weick, M., Thomas, D., Colbe, H., & Franklin, K. M. (2011). On-line ostracism affects children differentially from adolescents and adults. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 29, 110–123.

Abrams, D. , Powell, C. , Palmer, S. B. & Vyer, J. (2017). Toward a contextualized social developmental account of children’s group-based inclusion and exclusion. In The Wiley Handbook of Group Processes in Children and Adolescents (eds A. Rutland, D. Nesdale and C. S. Brown). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118773123.ch6.

Barhight, L. R., Hubbard, J. A., & Hyde, C. T. (2013). Children’s physiological and emotional reactions to witnessing bullying predict bystander intervention. Child Development, 84, 375–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01839.x.

Bennett, M., Yuill, N., Banerjee, R., & Thomson, S. (1998). Children’s understanding of extended identity. Developmental Psychology, 34(2), 322–331.

Bierman, K. L., Kalvin, C. B., & Heinrichs, B. S. (2015). Early childhood precursors and adolescent sequelae of grade school peer rejection and victimization. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44(3), 367–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.873983.

Buhs, E. S., Ladd, G. W., & Herald, S. L. (2006). Peer exclusion and victimization: processes that mediate the relation between peer group rejection and children’s classroom engagement and achievement? Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 1–13.

Doosje, B., Spears, R., & Ellemers, N. (2002). Social identity as both cause and effect: the development of group identification in response to anticipated and actual changes in the intergroup status hierarchy. British Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466602165054.

Epkins, C. C., & Heckler, D. R. (2011). Integrating etiological models of social anxiety and depression in youth: evidence for a cumulative interpersonal risk model. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 329–376.

Evers, C., Fischer, A. H., Mosquera, P. M., & Manstead, A. S. (2005). Anger and social appraisal: a “spicy” sex difference? Emotion, 5(3), 258–266. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.5.3.258.

Fox, C. L., Jones, S. E., Stiff, C., & Sayers, J. (2014). Does the gender of the bully/victim dyad and the type of bullying influence children’s responses to a bullying incident? Aggressive Behaviour, 40, 359–368.

Gnepp, J., McKee, E., & Domanic, J. A. (1987). Children’s understanding of situational information to infer emotion: Understanding emotionally equivocal situations. Developmental Psychology, 23, 114–123.

Hamilton, J. L., Potter, C. M., Olino, T. M., Abramson, L. Y., Heimberg, R. G., & Alloy, L. B. (2015). The temporal sequence of social anxiety and depressive symptoms following interpersonal stressors during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 495–509.

Harris, P. L., Olthof, T., & Terwogt, M. M. (1981). Children’s knowledge of emotion. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 22, 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1981.tb00550.x.

Harth, N. S., Leach, C. W., & Kessler, T. (2013). Guilt, anger, and pride about in-group environmental behavior: different emotions predict distinct intentions. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 34, 18–26.

Hawes, D. J., Zadro, L., Fink, E., Richardson, R., O’Moore, K., Griffiths, B., & Williams, K. D. (2012). The effects of peer ostracism on children’s cognitive processes. The European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9, 599–613.

Hawkins, D. , Pepler, D. J. and Craig, W. M. (2001), Naturalistic Observations of Peer Interventions in Bullying. Social Development, 10, 512–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00178.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York: The Guilford Press.

Hitti, A., Mulvey, K. L., Rutland, A., Abrams, D., & Killen, M. (2014). Exclusion of an ingroup member. Social Development, 23, 451–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12047.

Horton, P. (2011). School bullying and social and moral orders. Children & Society, 25, 268–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2011.00377.x.

Iyer, A., & Leach, C. W. (2008). Emotion in intergroup relations. European Review of Social Psychology, 19, 86–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463280802079738.

Jetten, J., Spears, R., & Manstead, A. S. R. (1997). Strength of identification and intergroup differentiation: the influence of group norms. European Journal of Social Psychology, 27, 603–609. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199709/10)27:5<603::AID-EJSP816>3.0.CO;2-B.

Jones, S. E., Manstead, A. S. R., & Livingstone, A. (2009). Birds of a feather bully together: group processes and children’s responses to bullying. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 27(4), 853–873.

Jones, S. E., Manstead, A. S. R., & Livingstone, A. (2011). Ganging up or sticking together: group processes and children’s responses to bullying. British Journal of Psychology, 102(1), 71–96.

Jones, S. E., Bombieri, L., Livingstone, A. G., & Manstead, A. S. (2012a). The influence of norms and social identities on children’s responses to bullying. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 241–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2011.02023.x.

Jones, S. E., Manstead, A. S. R., & Livingstone, A. G. (2012b). Fair-weather/his or foul-weather/his friends? Group processes and children’s responses to bullying. Social Psychology and Personality Science, 3, 414–420.

Killen, M., & Malti, T. (2015). Moral judgments and emotions in contexts of peer exclusion and victimization. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 48, 249–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.acdb.2014.11.007.

Killen, M., & Rutland, A. (2011). Children and social exclusion: morality, prejudice, and group identity. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Livingstone, A., Spears, R., Manstead, A., Bruder, M., & Shepherd, L. (2016). “Fury, us”: anger as a basis for new group self-categories. Cognition & Emotion, 30(1), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2015.1023702.

Malti, T., Strohmeier, D., & Killen, M. (2015). The impact of onlooking and including bystander behaviour on judgments and emotions regarding peer exclusion. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 33, 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjdp.12090.

Manstead, A. S. R., & Fischer, A. H. (2001). Social appraisal: the social world as object of and influence on appraisal processes. In K. R. Scherer, A. Schorr, & T. Johnstone (Eds.), Appraisal processes in emotion: theory, research, application (pp. 221–232). New York: Oxford University Press.

Masten, C. L., Eisenberger, N. I., Pfeifer, J. H., & Dapretto, M. (2010). Witnessing peer rejection during adolescence: neural correlates of empathy for experiences of social exclusion. Social Neuroscience, 2, 1–12.

Masten, C. L., Morelli, S., & Eisenberger, N. (2011). An fMRI investigation of empathy for “social pain” and subsequent prosocial behavior. NeuroImage, 11, 381–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.060.

Nesdale, D. (2007). Peer groups and children’s school social exclusion: scapegoating and other group processes. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 4, 388–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405620701530339.

Nesdale, D., Durkin, K., Maass, A., & Griffiths, J. (2005). Threat, group identification, and children’s ethnic prejudice. Social Development, 14, 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2005.00298.x.

Nesdale, D., Milliner, E., Duffy, A., & Griffiths, J. A. (2009). Group membership, group norms, empathy, and young children’s intentions to aggress. Aggressive Behavior, 35, 244–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20303.

Palmer, S. B., Rutland, A., & Cameron, L. (2015). The development of bystander intentions and social–moral reasoning about intergroup verbal aggression. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 33, 419–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjdp.12092.

Park, Y., & Killen, M. (2010). When is peer rejection justifiable?: Children’s understanding across two cultures. Cognitive Development, 25, 290–301.

Parkinson, B. (1996). Emotions are social. British Journal of Psychology, 87, 663–683. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1996.tb02615.x.

Parkinson, B., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2015). Current emotion research in social psychology: thinking about emotions and other people. Emotion Review, 7(4), 371–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073915590624.

Parkinson, B., Fischer, A., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2005). Emotion in social relations: cultural, group and interpersonal processes. Hove, Sussex: Psychology Press.

Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Vieno, A. (2012). Individual and class moral disengagement in bullying among elementary school children. Aggressive Behavior, 38, 378–388. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21442.

Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Thornberg, R. (2017). Getting angry matters: going beyond perspective taking and empathic concern to understand bystanders’ behavior in bullying. Journal of Adolescence, 61, 87–95.

Rigby, K. (2005). Why do some children bully at school? The contributions of negative attitudes towards victims and the perceived expectations of friends, parents and teachers. School Psychology International, 26, 147–161.

Riva, P., & Eck, J. (2016). The many faces of social exclusion. In Riva, P. and Eck J. (Eds.) social exclusion: psychological approaches to understanding and reducing its impact (pp. 9–15). Springer International.

Robinson, M. D., & Clore, G. L. (2001). Simulation, scenarios, and emotional appraisal: testing the convergence of real and imagined reactions to emotional stimuli. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(11), 1520–1532. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672012711012.

Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: a review. Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 15(2), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007.

Sani, F., & Bennett, M. (2004). Developmental aspects of social identity. In M. Bennett & F. Sani (Eds.), The development of the social self (pp. 77–100). New York: Psychology Press.

Scherer, K. R., Schorr, A., & Johnstone, T. (Eds.). (2001). Appraisal processes in emotion: theory, methods, research. New York: Oxford University Press.

Schott, R. M., & In Søndergaard, D. M. (2014). School bullying: new theories in context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sentse, M., Scholte, R., Salmivalli, C., Voeten, M. (2007). Person-group dissimilarity in involvement in bullying and its' relation with social status Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 1009–1019.

Smith, E. R. (1993). Social identity and social emotions: toward new conceptualizations of prejudice. In D. M. Mackie & D. L. Hamilton (Eds.), Affect, cognition, and stereotyping: interactive processes in group perception (pp. 297–315). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Smith, P. K. (2004), Bullying: Recent developments. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 9, 98–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2004.00089.x.

Thomas, E., McGarty, C., & Mavor, K. I. (2009). Transforming “apathy into movement”: the role of prosocial emotions in motivating action for social change. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 13(4), 310–333.

Trach, J. & Hymel, S. ( 2019). Bystanders’ affect toward bully and victim as predictors of helping and non-helping behaviour. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12516.

Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2007). The psychological structure of pride: A tale of two facets. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 506–525.

Van Der Schalk, J., et al. (2015). The social power of regret: the effect of social appraisal and anticipated emotions on fair and unfair allocations in resource dilemmas. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144(1), 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000036.

Vanhalst, J., Soenens, B., Luyckx, K., Van Petegem, S., Weeks, M. S., & Asher, S. R. (2015). Why do the lonely stay lonely? Chronically lonely adolescents attributions and emotions in situations of social inclusion and exclusion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 932–948.

Vrijhof, C. I., Van den Bulk, B. G., Overgaauw, S., Lelieveld, G., Engels, R., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2016). The prosocial Cyberball game: compensating for social exclusion and its associations with empathic concern and bullying in adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 52, 27–36.

Will, G. J., Crone, E. A., van den Bos, W., & Güroğlu, B. (2013). Acting on observed social exclusion: developmental perspectives on punishment of excluders and compensation of victims. Developmental Psychology, 49(12), 2236–2244.

Williams, K. D. (2009). Ostracism: a temporal need-threat model. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 41, 275–314.

Zdaniuk, B., & Levine, J. M. (2001). Group loyalty: Impact of members’ identification and contributions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37(6), 502–509. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.2000.1474.

van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T., & Spears, R. (2008). Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: a quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 504–535. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.504.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Jones, S.E., Rutland, A. Children’s Social Appraisal of Exclusion in Friendship Groups. Int Journal of Bullying Prevention 2, 129–138 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-019-00022-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-019-00022-w