Abstract

Commercial mold powders use a limited number of main mineral constituents, but may differ significantly in chemical composition. The main mineral raw materials of specimens investigated here are quartz, fluorite and free carbon, as well as wollastonite and carbonates. The investigations revealed the use of secondary raw materials like blast furnace slag, fly ash, glass scrap and phosphorous slag as further components. Since the formation of cuspidine was one major point of interest, the influence of the silica source on its formation was identified. A replacement of wollastonite by blast furnace slag reduced the temperature of the first precipitation of cuspidine by about 100 °C; the dissociation of sodium carbonate was lowered by ~ 40 °C. The lowest temperature of the first Na2CO3 dissociation could be achieved by using fluorine in combination with blast furnace slag. Cuspidine formation from the melt is further decreased if sodium and fluorine are both present. The use of glass scrap and phosphorous slag strongly reduced the temperature of first melt formation and enhanced cuspidine formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Mold powders are used in the continuous steel casting process and are added to the meniscus in the mold to facilitate this procedure. Due to the high temperatures within the mold, the powder melts and infiltrates the gap between the mold and the strand to act as a lubricant and to control the heat flow. One of the most important concerns in the continuous casting process is providing stable casting conditions and guaranteeing the appropriate product surface qualities. Thus, the melting behavior of the mold powder is of major importance since it controls the liquid slag pool depth on the meniscus [1, 2]. Furthermore, the size and shape of the slag rims formed in the meniscus zone are affected by the melting properties of the powder [3,4,5]. Usually, only the chemical composition of the material is reported on the data sheet, but the melting procedure is determined by the mineralogical composition (silicates, oxides and carbonates) [1, 5, 6]. The melting rate is also controlled by the types of carbon added [4, 7,8,9,10].

Using the commonly applied methods for the characterization of the melting behavior (e.g., heating microscope [7, 11, 12], molten flux drip test [8, 10] and simultaneous thermal analysis [13, 14]), no information can be determined regarding the reactions taking place within the mold powder during heating. By employing a hot-stage X-ray diffraction analysis, the crystalline parts of the mold powder depending on the temperature can be detected [13, 15]. The investigation of quenched samples provides the opportunity to study the phase reactions by freezing the melting process [16,17,18].

Because mold powders are a mixture of different raw materials, rather a melting range exists instead of a melting point. Therefore, the formation of several powder layers in the mold representing different sintering states is reported [19,20,21]. Depending on the composition, the liquidus temperature ranges from 1100 °C to 1250 °C [22, 23].

The lowest eutectic temperature of a mold flux system is an important factor because it controls the liquefaction process of the mold flux [20]. The addition of Na2CO3 as a raw material decreases the fluidity temperature [21]. The melting behavior is strongly influenced by the amount of carbonates present in the mix [24], and CO2 gas is formed during heating [19]. Kim et al. [20] investigated the decomposition of Na2CO3 in contact with SiO2 in detail and reported the formation of NaSiO3, Na6Si2O7 and a liquid. Due to the reaction with SiO2, the starting temperature of decomposition was found to be 770 °C instead of 850 °C of pure Na2CO3. If spodumene is applied instead of SiO2, the eutectic temperature decreased even further. The dissociation temperature of calcite (CaCO3) in contact with quartz is also decreased [16].

It was observed that when the powder melts, secondary phases are formed. The most abundant phases in the fluxes at higher temperatures are cuspidine (Ca4Si2O7F2), a pectolite phase (NaCa2Si3O8) and combeite (Na2Ca2Si3O9). When alumina is added to the powder anorthite (CaAl2Si2O8), gehlenite (Ca2Al2SiO7) and nepheline (NaAlSiO4) [21] are present.

Nevertheless, little is known about the reaction sequence taking place during melting. It is reported that mold powders containing sodium, wollastonite and fluorite will form combeite due to the diffusion of sodium into wollastonite. The development of cuspidine crystals starts at the surface of the wollastonite particles [25, 26]. However, the exact phase transformations are not clear and thus, the aim of this work is to identify the reactions taking place during the melting of mold powders. A main focus of this study is the examination of the influence of secondary raw materials on the phase formation and the melting behavior, since their role in the melting process is not known.

2 Experimental

2.1 Samples

Ten commercially available mold flux samples from three different brands were investigated. They were obtained in powder state or granulated. The range of the chemical composition is given in Table 1. The carbon content represents the amount of free carbon and the carbon contributed by carbonates.

Additionally, 9 model powders were examined regarding their high-temperature behavior. Those powders had simpler compositions, which facilitated the determination of the influence of single raw material components like wollastonite (CS), blast furnace slag (BFS), fluorite (CaF2) or sodium carbonate (Na2CO3). The mixing ratios of the single components for the model samples are listed in Table 2. The chemical composition of the BFS used herein is given in Table 3.

2.2 Methods

First, the mineralogical compositions of the mold powders were analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) with a Bruker D8-Advance diffractometer and polished sections were investigated with reflected light microscopy (Olympus AX70) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Carl Zeiss EVO MA15) in combination with an energy-dispersive X-ray analysis (EDX, Dry Cool Oxford Instruments). For the investigation of the melting behavior, simultaneous thermal analyses (STA, Netzsch STA 449 F3) were performed in combination with a thermogravimetric examination (TG). For the analysis, 100 mg from each investigated sample was heated to 1350 °C with a heating rate of 5 °C min−1 within a platinum crucible while purging with synthetic air (40 mL/min). In Fig. 1, an example for an STA/TG result of a mold powder for the production of high carbon steel is shown. In this case, the mass loss related to chemisorbed water is overlapped by the mass loss due to carbon combustion. A region representing water losses due to physisorbed water was not observable. The mass decreased by about 12 wt.% due to the combustion of carbon and the dissociation of the carbonates. The losses of volatiles started at around 980 °C and led to a further mass decrease of 1.6 wt.%.

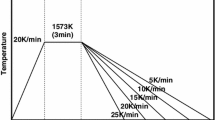

The STA only reveals thermodynamic effects and does not provide any information about microstructural changes. For the determination of the microstructural and mineralogical changes during heating, the samples were annealed stepwise within steel crucibles (30 mm × 30 mm × 40 mm) utilizing a high-temperature chamber furnace (Carbolite RHF 16/8). This stepwise annealing was done under air but without purging. Based on the first STA results, the temperature steps were fixed at 500, 750, 900, 1000, 1100, and 1200 °C to allow better comparability between the single powders. The dwell time at maximum temperature was fixed at 15 min. After that, the samples were quenched within the crucibles to room temperature. Subsequently, the specimens were analyzed by XRD and microscopic means. As the atmosphere was air during heat treatment, the steel crucible oxidized to Fe2O3. For treatment temperatures up to 1100 °C, the Fe2O3 content increased only in the outer edge of the samples. Therefore, for further investigation, only the middle of the heat treated specimen, where the Fe2O3 content was not influenced by steel oxidation, was used. The influence was significant for the samples after annealing at 1200 °C where the Fe2O3 amount increased also in the middle of the sample.

For the in situ observation of the melting behavior, the hot stage microscope (HSM, Linkem TMS 94) was applied. With this investigation method, the surface of a pressed mold powder sample that is located in a platinum crucible within a furnace is directly examined during heating with the help of a reflected light microscope. The main goal of this examination is the in situ observation of structural changes of the single mineral phases during heating. To accurately determine the specimen temperature, a looped thermocouple is inserted into the crucible placed in contact with the pressed mold powder [27].

3 Results

3.1 Secondary raw materials in commercial mold powders

As silicate source, natural raw materials like wollastonite, albite and quartz were identified as mold powder constituents. In addition, synthetic substances such as glass scrap (GS), phosphorous slag (PS), blast furnace slag (BFS) and fly ash (FS) were also observed (Table 4). The secondary raw materials contribute substantially to the overall SiO2 content of the mold powders due to their high silica content. To reduce the viscosity of the mold slag, fluorine is added usually in the form of fluorite (CaF2). Occasionally, cryolite (Na3AlF6) or villiaumite (NaF) is added. Another source of fluorine is the PS. Sodium oxide lowers both the melting point and the viscosity of the mold powder [28]. In addition to the sodium already present in the silicates and cryolite, the desired sodium content is achieved through the use of sodium carbonates. In the case of a granulation process with spray drying, a precipitation process leads to the formation of shortite (Na2Ca2(CO3)3) and/or gaylussite (Na2Ca(CO3)2 · 5H2O), and this process is similar to known reactions in the glass industry [29]. In particular, large amounts of shortite and gaylussite are formed in the presence of BFS and PS. However, when calcium is incorporated with wollastonite, these phases are scarcely present in the granules. The reason for this is that calcium ions are more easily released from a glass network than from a crystal lattice, and the presence of calcium-containing glass phases, like in the case of BFS, favors the formation of sodium–calcium carbonates. The comparatively low calcium content of the GS is not sufficient to form sodium–calcium carbonates, so these double carbonates were not detected in the mold powders based on GS.

To control the melting rate, different carbon carriers are used. Based on the STA analysis, crystalline graphite, amorphous carbon black and petcoke can be distinguished. The combustion of carbon black and graphite can be seen in Fig. 1. The differentiation of both and their influence on the behavior of the mold powder in use were not the goal of this investigation, for which the selected examination methods would not be suitable. In small quantities, calcite (CaCO3), magnesite (MgCO3), periclase (MgO) and alumina (Al2O3) are used to correct the chemical composition of the powder. Exceptions are calcium aluminate-based mold powders in which alumina is a major component. On rare occasions, lithium carbonate (Li2CO3) or spodumene (LiAlSi2O6) is used as lithium carrier.

In Fig. 2a, the microstructure of a granule of powder 4 is depicted, showing PS, fluorite, spodumene, gaylussite, calcite and wollastonite. The single constituents of the PS grains were found to be wollastonite (middle gray), cuspidine (bright gray), and glass phase (dark gray). Figure 2b shows an overview of granules of powder 5 in which FS and GS were used as secondary raw materials in addition to wollastonite, fluorite, quartz, calcite and shortite.

3.2 Stability of secondary raw materials in mold powders

To determine the performance of the commercial mold powders during use, it is necessary to investigate the mineralogical and structural changes with increasing temperature. This was done by using an HSM where the oxidation, dissociation, melting or crystallization of the single constituents was observed in situ. The temperature stabilities of the most important mold powder components are summarized in Table 5, which reflects the large bandwidth of the investigated samples. For example, there is a large difference between the minimum temperature of the liquid phase formation (598 °C) and the maximum observable temperature (1020 °C). Something similar was found for the stability of the GS where at least a difference of ~ 200 °C was determined, which shows how largely the single mold powder constituents influence each other.

Considering only the minimum values, the carbonates start to dissociate at very low temperatures and the cuspidine formation begins between 470 and 580 °C due to solid diffusion processes. The dissolution temperatures of the PS and GS are much lower compared to those of other silicate raw materials, while that of BFS is ~ 100 °C higher than that of wollastonite. Similar as wollastonite, the FS starts to dissolve around 600 °C, but the dissolution starting points were never observed to be at temperatures above 700 °C. On the contrary, the wollastonite dissolution seems to be influenced to a greater extent by other constituents. This can be seen by the strong difference in minimum (600 °C) and maximum (1000 °C) dissociation temperature.

3.3 Phase composition in model powders with increasing temperature

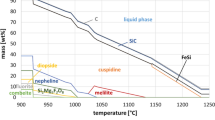

During the melting process, interstitial phases are formed in the mold powder. The most important and common main phase that forms in the presence of fluorine is cuspidine (Ca4Si2O7F2). With the help of stepwise annealing of the model powder MP 1 (Table 2), the cuspidine formation was investigated mineralogically. The estimated reaction sequence according to the ternary system SiO2–CaO–CaF2 described by Watanabe et al. [30] is as follows:

where L represents a liquid phase.

An STA investigation showed the appearance of cuspidine at 1023 °C. This finding was confirmed by a mineralogical investigation after annealing at 1120 °C, which found that cuspidine, fluorite and two liquids were present. To figure out the influence of BFS on cuspidine formation, a model powder with only slag and fluorine was manufactured (MP 2). The BFS shows a similar CaO/SiO2 ratio as wollastonite, but introduces many other oxides into the system while CS does not. The STA analysis of this sample showed an exothermal peak at 1030 °C corresponding to cuspidine formation. Moreover, the stepwise annealing process showed the formation of cuspidine up to 1100 °C.

In some commercial mold powders, CS and BFS are both used as raw material components. Therefore, it is of interest how both materials influence the cuspidine formation together. This was investigated based on MP 3, 4 and 5 in Table 2 where CS, BFS and CaF2 were mixed together in different ratios. The STA results of the three powders were compared. Due to the recrystallization of the slag, an exothermal peak was observed for all three powders at an onset temperature of ~ 760 °C. For the powder MP 5, which had the highest amount of slag, the peak area is the largest. The start of liquid phase formation for MP 3 and 4 is ~ 960 °C, and for MP 5, the starting temperature for liquefaction is higher (1010 °C). The melting is accompanied by the formation of cuspidine starting around wollastonite and BFS grains at 925 °C.

Sodium carbonate reduces the melting point of a mixture; thus, it is frequently applied as mold powder constituent. As a carbonate, it dissociates before starting to melt when exposed to high temperatures. It is of great significance to figure out how the dissociation behavior of carbonates is influenced by the presence of different silicates.

Initially, the influence of wollastonite was only investigated with model powder MP 6. With the help of a TG analysis, the CO2 loss of the carbonate was measured. The dissociation begins at 625 °C, and at 1190 °C, the whole carbonate was deacidified. After heat treatment at 1190 °C, different sodium and calcium-containing silicates and a glassy solidified liquid were identified. If wollastonite is completely replaced by BFS (MP 7), the temperature of the first dissociation decreases to 580 °C but the dissociation lasts until 1130 °C. In this model, powder sodium and calcium-containing silicates are formed from 870 °C upwards.

As fluorine carriers (CaF2) are also used besides silicates as raw materials frequently, it is important to know the combined effect on the dissociation behavior of the carbonates. Thus, two additional model powders MP 8 and 9 were manufactured. For MP 8, the recipe was chosen such that the influence of CS and fluorite on the dissociation behavior could be clarified. With this phase compilation, the dissociation temperature further decreased to 560 °C. The presence of fluorine leads to the formation of villiaumite starting at 575 °C and later to the evolution of cuspidine at 625 °C. After annealing at 1220 °C, only a glassy solidified melt was present. If CS is replaced by BFS as the case for MP 9, the dissociation temperature of Na2CO3 is further decreased to 520 °C. A similar effect was observed for MP 8; villiaumite and cuspidine were formed and the whole mixture was liquid after heat treatment at 1220 °C.

The most important determined values are summarized in Table 6.

4 Summary and discussion

4.1 Impact of substitution of wollastonite with blast furnace slag

To figure out the significance of replacing wollastonite with BFS, the described model powders were investigated. The assumption of cuspidine formation from Watanabe et al. [30] was confirmed through these investigations. Cuspidine forms primarily in the presence of a liquid phase. Notably, cuspidine is also formed by solid-state diffusion at the wollastonite grain boundaries at low temperatures. By replacing the wollastonite with BFS, cuspidine crystallizes from the melt 110 °C earlier. The melting point of the whole mixture dropped from 1214 to 1160 °C. The simultaneous presence of wollastonite and BFS lowers the liquidus temperature by another 60 °C independently of the mixture ratio (CS:BFS).

The addition of sodium carbonate to the mixture has a long-lasting effect on the formation of cuspidine. In the absence of sodium carbonate, cuspidine is mainly formed due to crystallization from a melt, but in the presence of sodium carbonate, the formation proceeds largely through solid-state diffusion. Thus, the dissociation temperature of the carbonates strongly affects the temperature of the first cuspidine formation and is substantially influenced by the type of silicate source used in the mixture. It was found that in the presence of wollastonite, the deacidification of sodium carbonate begins at 625 °C, while in presence of slag, it is lowered to 580 °C. If wollastonite and fluorite are both present, then the temperature of dissociation is decreased to 560 °C; replacing CS with slag leads to a decrease of further 40 °C to 520 °C.

Remarkably, cuspidine can incorporate sodium into its lattice, and this was also evident in the experimental samples. Subsequently, sodium ions diffuse into the silicate phases. Only as a second step, fluorine ions diffuse into the sodium–calcium silicate phases and react with them to form cuspidine and sodium-rich liquid phases.

The ability of sodium to lower the melting temperature was observed with these experimental powders. The liquidus temperature of the mixture with wollastonite and fluorite was 1214 °C, while it was lowered to 1130 °C when sodium carbonate was added. When slag is used instead of wollastonite, this effect was similar; here the liquidus temperature was reduced from 1160 to 1080 °C, which is, however, still the lowest melting point compared to all other model powders.

4.2 Phase development in commercial mold powders during heating

The dissociation of the carbonates is closely related to the formation of the first liquid phases. At 63 °C, sodium bicarbonate starts to dissociate to sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), water (H2O) and carbon dioxide (CO2), according to Eq. (2) [30].

The conversion of the bicarbonates starts below 350 °C as the results of the stepwise annealing show. The lowest dissociation temperature of Na2CO3 in the model powders was 520 °C, but in the commercial mold powders, the stepwise annealing process revealed the beginning of the dissociation of the sodium carbonate, the calcite and the sodium–calcium carbonates already at temperatures below 500 °C.

After annealing at 750 °C, reactions were observed as follows [16]:

Instead of calcite (CaCO3), other carbonates such as natrite, gaylussite, shortite and lithium carbonate can be used. The reactants can be quartz, wollastonite, synthetic glass phases, albite and spodumene. Because fluorite, cryolite and NaF are often present, the dissociation is accompanied by solid diffusion resulting in the formation of cuspidine. In most cases, the first liquid is formed and the sodium–calcium silicate phases crystallize from this liquid. The first reaction partner of sodium carbonate is usually quartz. Figure 3 shows the formation of a liquid phase around a quartz grain after annealing at 750 °C.

Instead or in addition to quartz, GS and PS also contribute to the formation of the liquid phase. The reaction equations are as follows:

The diffusion of sodium ions into the synthetic silicates, as can be seen in Fig. 4, decreases the melting point or melting range of those phases.

In the case of the presence of natural wollastonite, the sodium ions diffuse into the interior of the grain and form the mineral combeite (Na2Ca2Si3O9) without involvement of a liquid phase, as described in Ref. [25]. It was observable after annealing at 750 °C (Fig. 5a).

As a consequence, CaO diffuses to the grain boundaries, where as a next step cuspidine is formed according to Eq. (6):

Residual wollastonite could be detected by EDX at temperatures up to 1000 °C. It can be concluded that especially with larger wollastonite granules, the amount of sodium and/or the time for a complete conversion was insufficient. The presence of a melt accelerates the conversion process. The wollastonite of the PS also absorbs sodium oxide, but it reacts in the presence of the glass phase to NCS2 (Na2CaSi2O6).

Similar to the natural wollastonite, synthetic wollastonite introduced by the PS forms a ring of cuspidine around the NCS2 phase, while unlike natural wollastonite, the surrounding glass phase is involved in the reaction [Eq. (7)]. If the PS is present next to a sufficient quantity of quartz, then the wollastonite of the slag firstly forms a liquid from which later fluorpectolite (NaCa2Si3O8F) crystallizes.

The glass phase of the PS began to melt at 600 °C, while cuspidine and wollastonite domains maintained their crystallinity within the melt (Fig. 5b). It is interesting that although cuspidine is already present in crystalline state in the slag grains, it still incorporates sodium ions into its lattice at temperatures between 750 and 900 °C. Above these temperatures, cuspidine is free of sodium again and represents the last phase to melt in the mold powder.

Based on the stepwise annealing experiments, especially GS absorbs sodium and forms a liquid phase between 670 and 750 °C. At the same time, cuspidine is formed around this liquid.

The melting of the BFS began relatively late and was in the presence of quartz and carbonates observed to start at 750 °C. Solid diffusion of sodium, calcium and fluorine in the slag grains is noticeable. According to Eq. (8), the CaF2 reacts with the silicates to form cuspidine while the Na2O contributes largely to liquid phase formation.

The dissolution of these recrystallized slag grains occurred at temperatures between 757 and 1123 °C, as examined with the HSM. Fly ash is present in different amounts in almost all the investigated mold powders, and it dissolves within the melt between 750 and 1000 °C. However, as with all other silicates, a solid diffusion of sodium ions into the interior of the grains occurs previously. Thus, fly ash does usually not contribute to the formation of the first melt.

5 Conclusions

The main components of the investigated commercial mold powders are quartz, wollastonite, carbonates as well as secondary raw materials like blast furnace slag, fly ash, glass scrap or phosphorous slag. During heating of the powders, phase transformations take place, which are strongly determined by the used raw material system.

A combined use of fluorite and blast furnace slag leads to the lowest temperature of first dissociation of carbonates. The temperature of the first emergence of larger liquid phase amounts is related to the used silicate source. Especially, the presence of glass scrap in a mold powder promotes the formation of a melt at comparatively low temperatures.

Cuspidine is mainly obtained by precipitation out of the liquid, and thus a decrease in the melting point leads to an earlier cuspidine formation. The use of blast furnace slag instead of wollastonite lowers the temperature of first precipitation. Sodium addition will decrease the melting point as well and thus regulate the cuspidine formation. As it is introduced with glass scrap, this secondary raw material contributes largely to cuspidine formation. Fluorine reduces the viscosity of the liquid and thus facilitates the crystallization of cuspidine. Phosphorous slag itself introduces cuspidine and reduces the melting point as well; hence the phase formation is influenced along with Na2O.

References

C.A. Pinheiro, I.V. Smarasekera, J.K. Brimacombe, Iron Steelmak. 22 (1995) 43–44.

J.A. Kromhout, D.W. van der Plas, Ironmak. Steelmak. 29 (2002) 303–307.

I. Marschall, N. Kölbl, H. Harmuth, in: T.R. Bieler (Ed.), MS&T'2010, Materials Science & Technology 2010 Conference & Exhibition, ASM International, Houston, USA, 2010, pp. 1591–1600.

J.A. Kromhout, R.C. Schimmel, Ironmak. Steelmak. 45 (2018) 249–256.

I. Marschall, G. Xia, N. Kölbl, BHM 163 (2018) 23–28.

M. Kawamoto, K. Nakajima, T. Kanazawa, K. Nakai, Iron Steelmak. 20 (1993) 65–70.

D. Singh, P. Bhardwaj, Y.D. Yang, A. McLean, M. Hasegawa, M. Iwase, Steel Res. Int. 81 (2010) 974–979.

E.F. Wei, Y.D. Yang, C.L. Feng, I.D. Sommerville, A. McLean, J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 13 (2006) No. 2, 22–26.

E. Benavidez, L. Santini, E. Brandaleze, J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 103 (2011) 485–493.

W. Yang, Y.D. Yang, W.Q. Chen, M. Barati, A. McLean, Can. Metall. Quart. 54 (2015) 467–476.

D. Sighinolfi, M. Paganelli, IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 18 (2011) 222007.

A. Cruz-Ramirez, M. Vargas-Ramirez, M.A. Hernandez-Perez, E. Palacios-Beas, J.F. Chaves-Alcala, Rev. Metal. 48 (2012) 245–253.

M. Dapiaggi, G. Artioli, C. Righi, R. Carli, J. Non-Cryst. Solids 353 (2007) 2852–2860.

R.H. Gronebaum, P. Pischke, Stahl Eisen 127 (2007) 51–58.

J.A. Kromhout, M. Kawamoto, M. Hanao, Y. Tsukaguchi, E.R. Dekker, R. Boom, Steel Res. Int. 80 (2009) 575–581.

K.H. Spitzer, J.F. Holzhauser, F.U. Brückner, B. Siera, H.J. Grethe, K. Schwerdtfeger, Stahl Eisen 108 (1988) 441–450.

J.W. Kim, S.K. Kim, Y.D. Lee, in: A. Normanton (Ed.), CONCAST, 4th European Continuous Casting Conference, Institute of Materials, Minerals and Mining, Birmingham, UK, 2002, pp. 371–377.

P. Grieveson, S. Bagha, N. Machingawuta, K. Liddell, K.C. Mills, Ironmak. Steelmak. 15 (1988) 181–186.

R. Bommaraju, in Iron and Steel Society of AIME (Ed.), 74th Steelmaking Conference, Washington Meeting, Iron and Steel Society, Washington, USA, 1991, pp. 131–146.

J.W. Kim, Y.D. Lee, H.G. Lee, ISIJ Int. 41 (2001) 116–123.

A. Cruz, F. Chávez, A. Romero, A. Palacios, V. Arredondo, J. Mater. Process. Technol. 182 (2007) 358–362.

A.K.M. Attia, M.S. Hassan, M.E.H. Shalabi, A.A. El-Maksoud, Metall. Italiana 1 (1999) 55–60.

A. Delhalle, M. Larrecq, J.F. Marioton, P.V. Riboud, in: Iron and Steel Society of AIME (Ed.), 69th Steelmaking Conference: Fifth International Iron and Steel Congress, Washington Meeting, Iron and Steel Society, Washington, USA, 1986, pp. 145–152.

K. Schwerdtfeger, Metallurgy of continuous casting, Stahleisen, Düsseldorf, Germany, 1992, pp. 233–255.

R. Carli, R. Righi, M. Dapiaggi, in: R. Bruckhaus (Ed.), ECCC2011: 7th European Continuous Casting Conference, METEC, Düsseldorf, Germany, 2011, Session 9.

N. Kölbl, I. Marschall, H. Harmuth, in: M. Sanchez (Ed.), Molten 2009: VIII International Conference on Molten Slags Fluxes and Salts, Gecamin Ltd., Santiago, Chile, 2009, pp. 1041–1052.

N. Kölbl, H. Harmuth, in: J.O. Wikström (Ed.), Scanmet III: 3rd International Conference on Process Development in Iron and Steelmaking, Mefos, Lulea, Sweden, 2008, pp. 73–81.

I. Sohn, D.J. Min, Steel Res. Int. 83 (2012) 611–630.

K.H. Maletzki, Silikattechnik 31 (1980) 241–245.

T. Watanabe, H. Fukuyama, K. Nagata, ISIJ Int. 42 (2002) 489–497.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding is provided by Montanuniversität Leoben. The research program of the “metallurgical competence center” (K1-MET) is supported within the Austrian program for competence centers COMET (Competence Center for Excellent Technologies). Moreover, this work was supported by the industrial partners voestalpine Stahl GmbH and RHI Feuerfest GmbH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Marschall, I., Kölbl, N., Harmuth, H. et al. Identification of secondary raw materials in mold powders and their melting behavior. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 26, 403–411 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42243-019-00254-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42243-019-00254-6